Knossos

Knossos ( Greek Κνω (σ) σός Knōs (s) os ( f. Sg. ), Latin Cnossus or Cnosus , Egyptian Kunuša , Mycenaean ??? Ko-no-so in linear script B ) was an ancient place on Crete , about five kilometers south from Heraklion . It is best known for the Palace of Knossos , which, along with the palaces of Malia , Phaistos and Kato Zakros, is the largest Minoan palace on Crete and has been awarded the European Heritage Seal by Greece . Even after the palace was destroyed, Knossos remained populated until the Byzantine period.

history

Knossos was already settled during the ceramic Neolithic . The oldest traces of the up to eight meters thick settlement layers date from the 7th millennium BC. BC (6900-6600 BC). Immigrants, perhaps from Asia Minor, first brought farm animals and plants with them to the southern Aegean. Your settlement probably only existed for a few centuries (200–400 years). This is followed by a gap that dates back to about 5700-5500 BC. Chr. Is enough. The following new settlers show the typical cultural features of the early Neolithic. At the end of the 3rd millennium BC BC, smaller kingdoms developed on the island, as one deduces from the larger palace complexes in Phaistos, Malia, Knossos and Kato Zakros . The Palace of Knossos was built between 2100 and 1800 BC. At the site of the Neolithic settlement. Knossos was especially big, rich and magnificent.

Like almost all palaces in Crete, Knossos was built between 1750 and 1700 BC. Chr. (According to traditional chronology, see below) destroyed by a severe earthquake , but soon rebuilt. In Knossos and the rest of Crete, this event marks the end of the older and the beginning of the younger palace period . On the foundations of the old palaces, new, even more elaborate ones were built. Knossos experienced its greatest heyday and developed into the leading Cretan city-state and probably the religious and political center of the island. At that time Knossos probably had the largest and most powerful fleet , whose ships sailed to the Phoenician, Egyptian and Peloponnesian ports and headed for the Cyclades , Athens and the Middle East. Knossos had two seaports, one at Amnissos , the other in Heraklion . Around 1650 BC BC followed by minor destruction by another earthquake.

The massive volcanic eruption of the so-called Minoan eruption on the Cycladic island of Santorini , which, according to scientific dating, possibly as early as 1628 BC. Took place in Knossos at the end of the early phase of the so-called New Palace period (according to traditional chronology, the New Palace period is dated to around 1700 to 1430 BC). However, the Santorin catastrophe does not correspond to any previously archaeologically verifiable destruction in Knossos. Depending on the date of the eruption, the finds in Knossos must also be dated around 100 years earlier or later. Therefore, in the search for visible consequences for Knossos, it does not matter whether one accepts the scientific or traditional date of the eruption. Around 1400 BC BC (according to traditional chronology) the city survived a severe earthquake almost undamaged thanks to the cedar wood built into the walls vertically and horizontally . The palace was built until 1370 BC. Used.

An invasion of the Mycenaean Greeks from the mainland at the beginning of the 14th century BC According to some archaeologists, BC led to the complete demise of the Minoan culture - possibly in connection with an uprising by the Mycenaeans who were already living on the island. According to one theory, the power of the Minoans had suffered a severe blow with the destruction of the fleet and all northern Cretan ports. In addition, ash deposits and a multi-year climatic deterioration caused by the eruption caused crop failures both further weakened the Minoan culture and undermined the authority of the ruling classes, which led to increasing instability and possibly also immigration of Mycenaean Greeks.

The Mycenaean conquerors destroyed everything in Knossos that the earthquake of around 1400 BC had caused. Had left unharmed. A fire that must have raged for several days and in which wood and oil gave the fire additional nourishment, destroyed around 1370 BC. The upper floors and many of the walls of the palace made of limestone and gypsum stone (often referred to as alabaster, sometimes very coarse crystalline). After that the palace was abandoned.

Knossos was repopulated in the Protogeometric Period. 343 BC Sparta sent its soldiers against Knossos, which was allied with Macedonia . Twenty years later, Crete came under Ptolemaic rule. 220 BC Chr. Gortyn replaced Knossos in the role of the Cretan capital. When the Romans in 189 BC Arrived in Crete, Knossos was again from 150 BC. BC Crete's capital. 67 BC The Romans made Gortys the capital of the new province of Creta et Cyrene , which included Crete and the Libyan Mediterranean coast. Since 36 BC It became a Roman colony under the name Colonia Iulia Nobilis . The Greek and Roman city was in the immediate vicinity of the palace, but only a small part of it has been excavated.

The titular diocese of Cnossus goes back to Knossos.

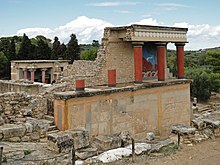

Archaeological site

The youngest palace of Knossos was created as a building ensemble of up to five floors with a built-up area of 21,000 m² on a clear area of 2.2 hectares. 800 rooms can be proven, but the palace may have had up to 1,300 in total. The palace was never fortified. Like all palace complexes of the Minoans, it is built around a rectangular central courtyard measuring 53 × 28 m. Angled, comparatively narrow corridors, richly decorated corridors, painted halls, elaborately designed stairwells and columned galleries approach this courtyard from four directions. The plant was the administrative center and contained numerous workshops.

These rooms and corridors are joined together in a confusing arrangement. There are doors and passages, stairs and ramps. Some rooms are connected by polythyra , interior walls that were designed as rows of ceiling-high, double-leaf doors between pillars. If they were closed, the rooms were partitioned off, a door was opened, there was a passage, if all doors were opened, the rooms were connected. There were also workshops and magazines, up to 400 pithoi, some of them head- high, full of wine, olive oil, grain or honey with a capacity of around 78,000 liters.

The heart of the palace is the so-called throne room, which was named because of an alabaster throne found there . Stone benches are set up on the side walls of the anteroom. A precious porphyry bowl stands in the center of the anteroom. It probably served ritual ablutions. Other interpretations interpret this as an aquarium.

On the north-western edge of the palace complex there is a staircase that meets at right angles, as can also be found in Phaistos. It closes a processional way coming from the west and is interpreted as a theater for about 500 people.

Infrastructure

According to archaeologists, in the 16th century BC the city had Between 10,000 and 100,000 inhabitants. Living rooms with hot water heating, bathrooms with hip baths and toilets with water flushing were excavated . The rain on the palace grounds was caught by carefully laid, conical pipes made of terracotta and covered, stone channels, the cisterns were comparatively small.

The nearby stream Kairatos (now Katsambas ), which some archaeologists assumed was navigable in large boats, can also be used as a drinking water supply. Many fountains were not found on the palace grounds. According to Strabo ( Geographika 10.4.8), Kairatos is said to have been an alternative name for the city of Knossos in addition to the naming of the brook. The port of Knossos was located at the mouth of the stream, at today's port of Heraklion. Another port of the city is said to have been the eastern Amnisos .

Frescoes

One of Arthur Evans' most exciting discoveries was the colored frescoes. Women's clothing preferred puff sleeves , slim waists and narrow skirts. The blue color of the clothing indicates sea trade with the Phoenicians . The frescoes represent sports competitions, probably of ritual importance, in which young men and girls acrobatically jump into the bull .

myth

According to the myth passed down by Homer about 700 years after the destruction of Knossos, in the 16th century B.C. The firstborn son of Zeus and Europa , the legendary King Minos , over Knossos. Minos was the husband of Pasiphaë and father of Ariadne and Androgeos . The god Poseidon gave Minos a wonderful white bull that he was to sacrifice to Zeus. But Minos liked the bull so much that he drove it to his herd and had another bull sacrificed in its place. As a punishment for this offense, Zeus kindled a desire for the animal in Pasiphaë. Pasiphaë settled by the royal architect Daedalus make a hollow wooden cow, which was covered with cowhide. Daidalos brought the wooden cow to the herd, whereupon the hidden Pasiphae with the divine bull fathered and gave birth to the bull-man Minotauros , a man-eating monster. King Minos did not have this monster with a human body and a bull's head killed, but commissioned Daidalos to build a safe hiding place, the fabulous labyrinth .

King Minos took the death of his son Androgeus in a sporting competition in Attica as an opportunity to force the Athenians every ninth year to pay tribute to seven young men and seven virgins, who were sacrificed to the Minotaur. Prince Theseus volunteered to be hostages to kill the Minotaur. When he met Minos' daughter Ariadne after his arrival in Crete, they both fell in love. Theseus confided in her his intentions, and she promised her help if he married her and took her to Athens. When he agreed, she gave him Daidalos' magical ball of wool, which he could use to find his way out of the labyrinth at any time. With the help of the gods, Theseus succeeded in slaying the Minotaur, which he sacrificed to Poseidon; Together with Ariadne and his fellow hostages, he then fled to Naxos, supported by the gods .

Interpretations

The Minoans may have had a matriarchal culture and may worship an earth, vegetation, and fertility goddess. For some researchers, the myth of King Minos symbolizes the transition from this culture to the patriarchal culture of the nomads who breed cattle .

The bull occupies a special position in the Minoan religion: at first it was perhaps worshiped as a sacred animal, but its unpredictability made it an enemy demon and thus a sacrificial animal. The Minoan bull games , in which young men and girls ritually jump over a bull and thus “overcome” it, could be rooted in this view.

The oversized cult horn, which is often found on the boundaries of the stairs and terraces of the palace, probably as a cult symbol, is modeled on a bull horn.

As the processional frescoes in Knossos show, the Minoan culture was influenced by Egypt . There the sun god Re was brought to heaven on the back of a heavenly cow. The cow is documented in the pyramid texts of the Old Kingdom ; she is identified with the goddesses Hathor and Neith .

The winding layout of the palace was probably the origin of the legend of the labyrinth (from Greek labrys , " double ax ", or loan word from ancient Egyptian, meaning "palace on the lake", based on the possible model of the labyrinth of Hawara ) in the Theseus killed the Minotaur. The double ax is a recurring motif on the palace walls and could possibly mean that the palace was originally referred to as the "house of the double ax". Only a few years ago was possible evidence of human sacrifice found in Knossos : on the site behind the Stratigraphic Museum , children's bones with cut marks were discovered.

Some researchers assume that the Minotaur of the Greek legend was the chief priest as a representative of the Cretan bull deity. The victory of Theseus could symbolize the victory of the Achaeans infiltrating from the mainland into Crete over the Minoans and their alleged matriarchy.

Research history

The wealthy Cretan businessman, lawyer and amateur archaeologist Minos Kalokairinos succeeded in discovering Knossos in 1878. He exposed two storage rooms with pithoi and cult objects. The Mecklenburg merchant and Troy discoverer Heinrich Schliemann , who suspected the palace of King Minos to be near Heraklion, visited the Knossos terrain in 1886 together with the archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld . Dörpfeld tried to get permission for a large-scale archaeological excavation from the German Archaeological Institute, whose director he became a little later in Athens. But the Turkish owner of the property demanded a purchase price of 100,000 gold francs that was too high for the Germans. After negotiating down to 40,000 francs, there were disagreements in the staking out of the property, which is why Schliemann postponed the purchase of the property from Knossos in favor of another excavation campaign in Troy , but died in 1890 before the intended acquisition of the property.

In 1894, the English museum director, ethnologist and newspaper correspondent Arthur Evans came to Crete for the first time in search of pre-Greek written documents. Finally, he became enthusiastic about the newly discovered pre-Greek Minoan culture on Kefala Hill. As a result of the Greek liberation struggle against the Ottoman government, he was only able to buy the area in 1900 through the mediation of the British-friendly High Commissioner. On March 23, 1900 Evans began systematic excavations in Knossos, which lasted until 1914. Excavations began almost simultaneously in Phaistos, Kato Zakros , Palekastro , Gournia , Lato and the Zeus cave Psichro . Arthur Evans had enough money to fulfill his lifelong dream of excavating Knossos. The newly established Cretan Exploration Fund Foundation contributed financially.

With the help of Duncan Mackenzie , who had recommended himself through the excavations on Melos Island , and Mr. Fyfe, the architect of the British School of Athens, Evans initially employed 30 workers on the excavations. But their number quickly grew to 200, with the help of which he uncovered 20,000 m² of the palace in three years. Since he was no longer interested in the Mycenaean development , they were removed without documentation.

Evans' idiosyncratic naming of rooms such as the throne room, the queen's bathroom, the caravanserai , the customs house and others earned him a lot of criticism from archaeologists. Many archaeologists see this as the suggestion of a reliable finding that by no means exists. His bold reconstructions are highly controversial as they cement these individual interpretations and make further research on the object (in situ) practically impossible. In his endeavor to preserve the exposed rooms and artefacts from decay and thus give the viewer an idea of the possible appearance of the former palace, he first experimented with wood imported from England and Scandinavia. When this did not have the expected longevity, he used the most modern and long-lasting building material at the time, concrete . But this is much heavier than ancient plaster of paris and wooden structures and, after almost a hundred years, needs constant restoration in view of the thousands of tourists a day. On the other hand, Evans must be viewed as a child of his time, when ancient ruins were restored in the spirit of philhellenism .

The effects of Emile Gilliéron who together with his son Emile (1885-1939) an important role in restoring (and thereby "artistically free") by frescoes and other finds was working at Knossos by Arthur Evans, possibly as fakes to consider .

Excavations of JD Evans in the 1960s laid layers of the Neolithic and Aceramic free Neolithic, which are among the earliest Neolithic finds in Greece. Todd Whitelaw from University College London has been conducting inspections in the area around Knossos since 2005 to shed light on the settlement history of the place.

Alternative interpretations

Due to the soft building stone, the German geologist Hans Georg Wunderlich had doubts about the conventional interpretation of the palace complex during his visit to Knossos in 1970. Two years later he presented his interpretation in the book Where the bull went to Europe, which focuses on the thesis that the Minoan palaces of Crete were not intellectual, cultural or political centers, but necropolises for burial of the dead. Wunderlich interpreted the lack of a fortification wall in spite of the exposed location as a cemetery calm, while the school view interprets this as the peacefulness of the epoch and the effectiveness of a strong fleet. Wells, water pipes, cisterns and drainage channels were interpreted by Wunderlich in connection with the preparation of the dead for embalming . Bathtubs became coffins, pithoi became grave sites and the colorful jugs with elongated pouring openings became aids in embalming the dead. He interpreted the light shafts of the palace as ventilation shafts for the necropolis. Until his death in 1974, Wunderlich's theses dominated many discussions at times.

The archaeologist and cave explorer Paul Faure believes that instead of Knossos, a ramified cave near Skontino , three and a half hours from Knossos, is the labyrinth.

literature

- Arthur Evans: The Palace of Minos: a comparative account of the successive stages of the early Cretan civilization as illustrated by the discoveries at Knossos. London ( digitized six volumes, 1921–1935).

- Hans Georg Wunderlich: Where the bull took Europe. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1972, ISBN 3-499-17198-8 (controversial interpretation of the palace as a city of the dead).

- Erik Hallager: The Mycenaean Palace of Knossos. Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm 1977, ISBN 91-7192-367-5 .

- Heinz Geiss. Travel to old Knossos. Prisma-Verlag Zenner and Gürchott, Leipzig 1981.

- Hans-Eberhard Giesecke: What did Knossos really look like? In: Talanta. Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society. Volume 16/17, 1984/85, ISSN 0165-2486 , pp. 7-52 ( digital copy [PDF; 3.3 MB; accessed on October 20, 2017]).

- Robin Hägg, Nanno Marinatos (Ed.): The Function of the Minoan Palaces. Proceedings of the international symposium at the Swedish Institute in Athens, 10. – 16. June 1984 (= Skrifter. Vol. 35). Åström's Förlag, Stockholm 1987, ISBN 91-85086-94-0 .

- Costis Davaras: Knossos and the Museum of Herakleion. Athens 1986.

- J. Wilson Myers, Eleanor Emlen Myers, Gerald Cadogan (Eds.): The Aerial Atlas of Ancient Crete. Thames and Hudson, London 1992, ISBN 0-500-05066-X .

- Rainer Vollkommer: New great moments in archeology (= Beck'sche series. No. 1727). CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-406-55058-4 .

- John G. Younger, Paul Rehak: The Material Culture of Neopalatial Crete . In: Cynthia W. Shelmerdine (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age . Cambridge 2008, pp. 140-164.

Web links

- Official site of the Greek Ministry of Education (Engl.)

- Knossos - The main palace of Minoan Crete. In: antikefan.de

- The Minoan Palace in Knossos. In: explorecrete.com

Individual evidence

- ^ Fritz Gschnitzer : Early Greekism: Historical and Linguistic Contributions . In: Small writings on Greek and Roman antiquity . tape 1 . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-07805-3 , pp. 5 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Katerina Douka et al .: Dating Knossos and the arrival of the earlisest Neolithic in the southern Aegean . In: Antiquity , Volume 91, No. 356 (April 2017), pp. 304-321, 317

- ↑ Carl Knappelt, Ray Rivers, Tim Evans: The Theran eruption and Minoan palatian collaps - new interpretations gained from modeling the maritime network. In: Antiquity , 85, 329, pp. 1008-1023.

- ^ Strabo : Geographika. 10.4.8. Perseus Project , accessed November 5, 2015 .

- ↑ Ivana Petrovic: From the gates of Hades to the halls of Olympus. Artemis cult with Theocrit and Callimachus . Brill, Leiden, Boston 2007, ISBN 978-90-04-15154-3 , The Amnisian Nymphs at Apollonios Rhodios, p. 261 ( books.google.de [accessed on November 5, 2015] digitized version).

- ↑ Hans Georg Wunderlich: Where the bull carried Europe . Anaconda Verlag GmbH, Cologne 2007, p. 288 and others .

- ^ Günther Kehnscherper : Crete, Mycenae, Santorin . 6th edition. Urania, Leipzig / Jena / Berlin 1986, Science of Spading, p. 15 .

- ↑ William H. Stiebing: Uncovering the Past: A History of Archeology . Oxford University Press, New York 1994, ISBN 0-19-508921-9 , p. 135.

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Snake Goddesses, Fake Goddesses. How forgers on Crete met the demand for Minoan antiquities. In: Archeology (A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America) Volume 54, No. 1, January / February 2001 ( abstract ).

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin was able to use the results of a 14 C dating ( radiocarbon method ) for the snake goddess in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and others to prove a modern production from medieval ivory; see also Kenneth DS Lapatin: Snake Goddesses, Fake Goddesses. How Forgers on Crete Met the Demand for Minoan Antiquities. In: Archeology. Volume 54, No. 1, 2001, pp. 333-336 ( abstract ); Kenneth DS Lapatin: Mysteries of the Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, and the Forging of History. Houghton Mifflin, Boston 2002, ISBN 0-618-14475-7 ; Judith Weingarden: Review of Kenneth DS Lapatin: "Mysteries of the Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, and the Forging of History." In: American Journal of Archeology. Volume 108, No. 3, 2004, pp. 459-460 ( academia.edu ).

- ↑ N. Efstratiou, A. Karetsou, ES Banou, D. Margomenou: The Neolithic Settlement of Knossos: New Light on an Old Picture . In: G. Cadogan, E. Hatzaki, A. Vasilakis (eds.): Knossos: Palace, City, State (= British School at Athens Studies 12 ). London 2004, p. 39-49 .

- ^ JD Evans: Excavations in the Neolithic Settlement of Knossos, 1957-60. Part I . In: The annual of the British School at Athens . tape 59 , 1964, pp. 132-240 .

- ↑ JD Evans [and a.]: Knossos Neolithic, Part II . In: The annual of the British School at Athens . tape 63 , 1968, pp. 239-276 .

- ^ JD Evans: Neolithic Knossos: the Growth of a Settlement . In: Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society . tape 37 , no. 2 , 1971, p. 95-117 .

- ^ JD Evans: The Early Millennia: Continuity and Change in a Farming Settlement . In: D. Evely, H. Hughes-Brock, N. Momigliano (eds.): Knossos: A Labyrinth of History . Oxford 1994, p. 1-20 .

- ^ C. Perlès: The early Neolithic in Greece: The first farming communities in Europe . Cambridge 2001.

- ^ Todd Whitelaw, J. Bennet, E. Grammatikaki, A. Vasilakis: The Knossos Urban Landscape Project 2005. Preliminary results . In: Pasiphae. Rivista di Filologia e Antichità Egee . tape 1 , 2008, p. 103-109 .

- ↑ T. Whitelaw, M. Bredaki, A. Vasilakis: The Knossos urban landscape project: investigating the long-term dynamics of landscape to urban . In: Archeology International . tape 10 , 2007, ISSN 1463-1725 , p. 28-31 ( ai-journal.com ).

Coordinates: 35 ° 18 ' N , 25 ° 10' E