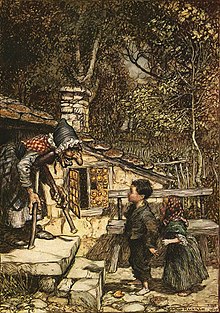

Hansel and Gretel

Hansel and Gretel is a fairy tale ( ATU 327A). It is in the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm at position 15 (KHM 15). There the title was written from the 2nd edition Hansel and Grethel . Ludwig Bechstein took it over after Friedrich Wilhelm Gubitz in his German fairy tale book as Hansel and Gretel (1857 No. 8, 1845 No. 11).

Content according to the version from 1812

Hansel and Gretel are the children of a poor woodcutter who lives in the forest with his wife. When the need becomes too great, she persuades her husband to abandon the two children in the forest. The next day, the lumberjack leads them into the forest. But Hansel overheard the parents and lays a trail of small white stones that the children can use to find their way back. So it happens that the mother's plan fails. But the second attempt to abandon the children succeeds: This time Hansel and Gretel only have a slice of bread with them, which Hansel crumbles to create a trail. However, it is picked up by birds. This means that the children can no longer find their way home and get lost. On the third day they come across a little house made entirely from bread, cake and sugar. First of all, they demolish parts of the house to satisfy their hunger. However, in this house lives a witch who is an ogre. Both in the original version of the fairy tales from 1812 and in the later editions up to the “last edition” from 1857, it calls out in a kind of onomatopoeia : “Knuper, knuper, kneischen, who is knocking at my little house?”

In Ludwig Bechstein's 1856 German Fairy Tale Book , the text, in contrast to the Brothers Grimm , reads : “ Knusper, crisper, kneischen! Who is nibbling at my house? “The children's answer, on the other hand, is identical in Bechstein and in the expanded version by the Brothers Grimm from 1819:“ The wind, the wind, the heavenly child ”.

The witch is not fooled, catches the two of them, makes Gretel a maid and feeds Hansel in a cage to eat him later. Hansel uses a trick, however: to check whether the boy is already fat enough, the half-blind witch feels his finger every day. Hansel holds out a small bone every time. When she realizes that the boy is apparently not getting fat, she loses patience and wants to fry him immediately. The witch orders Gretel to look into the oven to see if it is already hot. But Gretel claims to be too small for that, so that the witch has to look for herself. When she opens the oven, Gretel pushes the wicked witch inside. The children take treasures from the witch's house and find their way back to their father. The mother has since died. Now they live happily and no longer suffer from hunger.

The second version from 1819

In this version, the fairy tale is expanded. After the witch's death, the children do not find their way home at first, but come to a body of water that they cannot cross. Finally, a duck swims over and carries the children across the water. Then the area looks familiar to them and the children return. Ludwig Bechstein largely follows this second version by the Brothers Grimm in his “German Fairy Tale Book”, but adds a grateful white bird that has picked the crumbs and shows the children the way home after the witch's death.

Since the Brothers Grimm's version of 1840, it is no longer one's own mother, at whose instigation, the children are abandoned in the forest, but a stepmother .

origin

The sources for Wilhelm Grimm's handwritten original version from 1810 are unknown. His comment from 1856 notes on the origin: "According to various stories from Hesse." In Swabia, a wolf sits in the sugar house. He still calls Stahl "S. 92 The Sugar Factory '; Pröhle No. 40; Bechstein 7, 55; Stöbers The pancake house in "alsace. Volksbuch p. 102 “; Danish Pandekagehuset ; Swedish with Cavallius "S. 14. 26 "; Hungarian in Stier p. 43; Albanian with Hahn “164. 165 "; Serbian at Vuk No. 35; Zingerles The fairy tale of the Fanggen in children's and household tales ; a piece in Oberlin's Essai sur le patois ; Pentamerone 5.8; Aulnoy No. 11 Finette Cendron ; Zingerle p. 138; Cavallius 31. Grimm sees a connection to Däumling in German stories (KHM 37 , 45 ), in Zingerle “S. 235 der Thumb-long Hansel ”and Old German Forests “ 3, 178.179 ”. Grimm's comment on KHM 24 Frau Holle tells a similar fairy tale.

Compared to the handwritten original version from 1810, the first print from 1812 is more detailed, especially in the dialogues in the witch's house. The names of the children were inserted into the text in accordance with the new title, including the pious sayings “just sleep, dear Gretel, God will help us” and “God gave it to Gretel”. From the 2nd edition onwards, the father ties a branch to the tree in order to simulate the blow of an ax through the wind. That goes with “the wind! the wind ! the heavenly child! ”as the children answer the witch (according to Wilhelm Grimm's note from Henriette Dorothea Wild ). A snow-white bird brings the children to the witch's house (from 5th edition), a white duck carries them home across the water (from 2nd edition; cf. KHM 69 and 13 , 135 ). From the 5th edition onwards, the stepmother and the witch are paralleled with a similar speech (“get up, you idlers…”), she scolds the children as if they had willfully stayed in the forest for a long time, plus the saying “afterwards the song comes in The End"; "Who will say a, need to say b as well". In the original version, Hansel was locked up as a pig and from the first edition on as a “little chicken”, now he simply comes into a stable, “he could scream as he wanted”. From the 6th edition onwards, Wilhelm Grimm adds the characterization of the witch, probably based on KHM 69 Jorinde and Joringel : “Witches have red eyes and cannot see far, but they have fine weather, like animals, and notice when people are come up. "

Wilhelm Grimm borrowed from August Stöber's Das Eierkuchenhäuslein (1842), which, however, is itself based on Grimm's text. Walter Scherf believes that in Grimm's circles literary rather than oral tradition is to be expected, also in view of the spread of Perrault's and d'Aulnoy's fairy tales. The sugar house seems to be an invention of Biedermeier romanticism and could go back to Arnim's mention of a fairy tale that FD Gräter knew.

The fairy tale shows a polarization of good and bad, supported by oppositions: parents and witch houses, indoor and outdoor space, hunger and fattening, separation and reunion. The children rise again from the death intended for them by the stepmother and the witch. Cf. in Giambattista Basiles Pentameron I, 10 The battered old woman , V, 8 Ninnillo and Nennella . For the flight over the water cf. Styx or Mt 14.29 EU .

Influences and precursors

The fairy tale comes from oral tradition and was retold and illustrated by Franz von Pocci , in addition to the Brothers Grimm and Bechstein . It also appeared in 1844 in the German People's Calendar of Friedrich Wilhelm Gubitz . In the entrance motif , the fairy tale is dependent on Perrault's Le petit poucet , a thumble tale , where, in addition to the scattering of pebbles and bread, the motif of man-eating occurs.

The names "Hansel" and "Gretel" take up the most common baptismal names Johannes and Margarete and are often used as fictitious placeholders in this combination in the early modern period.

Bechstein

With Ludwig Bechstein , the fairy tale is told a little differently: The father takes the ax with him, but does not tie it to the tree. The witch's entertainment is more detailed, then she blocks Hansel's mouth so that he does not scream. A bird leads the children to the witch's house and warns Gretel when the witch tries to put them in the oven, the birds bring pearls as thanks for the breadcrumbs. On the way home she carries a swan. According to Hans-Jörg Uther , Bechstein stuck to Friedrich Wilhelm Gubitz 's Die Kinder im Walde in Deutscher Volkskalender for 1845 (1844).

Cf. The golden roe buck and The little Däumling in Bechstein's German Fairy Tale Book (in the 1845 edition also Fippchen Fäppchen and The Garden in the Fountain ) and From the boy who wanted to learn witches in New German Fairy Tale Book .

To the motive

In the original version by the Brothers Grimm, as well as in Ludwig Bechstein's collection of fairy tales, instead of a stepmother, it is still one's own mother, which gives the fairy tale a more socially critical meaning. The children are abandoned because the family is starving. At Bechstein's, the mother does not die, but worries about the children together with the father and regrets having sent them away. At that moment the children enter the house and the misery is over.

In the late version by the Brothers Grimm, the fairy tale resembles many stepmother's tales in its initial motif .

Psychoanalytic and other interpretations

The anthroposophist Rudolf Meyer understands the dove and "wind" as the spirit that comes into the body, where matter abuses it until the soul purifies it. According to Hedwig von Beit , the food-giving witch appears as the great mother , here dazzling childish dream fantasies. A bird leads to it, that is, intuitive dreaming out. The change takes place in the inner fire of passion (cf. KHM 43 , 53 ). The stove is also a symbol of the Great Mother, so she destroys herself and with it her counterpart, the failing stepmother. According to Bruno Bettelheim , the initial situation fits in with the widespread childish fear of being rejected by their parents and of having to starve to death. Hansel's path marking with pebbles is still appropriate, but the second time he succumbs to oral regression, bread as an image for food comes to the fore. This can also be seen in the fact that the children can eat from the gingerbread house. At the same time, the gingerbread house is also a picture of the (mother) body that nourishes the child before and after the birth. But the children have to learn to emancipate themselves from it. The great water that the children cross on their return without having met it first, symbolizes the maturation step that the children take as they plan their fate in their own hands. Gretel knows that you have to do it alone. With Hansel being the savior at the beginning of the fairy tale and Gretel at the end, the children learn to trust themselves, each other and their peers. Now they are a support for their parents' house and even contribute to the end of poverty with the treasures they brought with them. For Friedel Lenz the poor wood chopper is a gray thinker whose living soul has died, feeling and will are orphaned and succumb to occult temptation. When burning desire becomes the fire of purification, the view widens by the great water. The duck belongs to Apollo's sun chariot, Indian temples or the Russian fairy tale Elena the Wonderful . Ortrud Stumpfe states that there is no effective development in Hansel and Gretel : the children outsmart the dull force of nature, but then simply return to the children's milieu.

According to psychiatrist Wolfdietrich Siegmund , schizophrenics in their perplexity about good and evil are helped by the certainty that the witch is destroying herself. According to Johannes Wilkes , anorexic girls often talk to Hansel and Gretel or the table, set yourself up . For Eugen Drewermann , too , Hansel and Gretel described the experience of oral deficiency as the cause of feelings of depression and eating disorders. Homeopaths think of the motives of loneliness and lack of Calcium carbonicum , Medorrhinum or Magnesium carbonicum . According to Wilhelm Salber , repetitive actions have to do with the control of survival and are only masked by enthusiasm (witch house), while new coincidences (the duck as a means of transport) initiate real development. Recurring basic situations bring their own transformation with them. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum cites the fairy tale as an example of necessary and poisonous fear: hunger is real, but "the story invents an ugly, child-eating witch who is blamed as a scapegoat."

Parodies

Hansel and Gretel , a children's fairy tale and perhaps the best-known fairy tale of all, goes well with the ideal of simple form . Parodies are always on a very simple level. Roland Lebl thinks modern children are so factual that the narrating grandma runs away. Hans Traxler wrote The Truth about Hansel and Gretel , Paul Maar The story of the bad Hansel, the bad Gretel and the witch. Pumuckl on the witch hunt raises the alarm at Meister Eder because he believes the neighbor's fairy tale. Julius Neff wrote a parody. Iring Fetscher wrote Hansel and Gretel's Unmasking or An Episode from the History of Pre-Fascism and the Controversy about "Hansel and Gretel" . Karin Struck ironically interprets the witch in the oven as hatred of motherhood. Parodies such as Josef Wittmann's short poem or Wolfgang Sembdner's “Alphabetisch” (from “Armut” to “Zack”) take up social criticism with abandoning children and killing witches in a very simple way, as does Fritz Vahle (“The oven there / The old woman must go ... "). Wolfgang Sembdner tells the story with lots of poet names: “... a Thomas Mann lived there . He had two Wedekinder but no Max Brod in the Gottfried Keller … ”. At Josef Reding's , the child spreads the expensive peat out of the car on the way because they believed the fairy tale. Dieter Harder apparently wrote Hanselus Gretulaque in Latin . At Rudolf Otto Wiemer's home , the foster children find their non-Aryan grandmother in the forest and are picked up so that the father can be promoted to the NSDAP. Even Walter Moers ' novel ensel and krete uses the fairy tale. Beate Mitzscherlich and Ulla Hahn parodied the plot from the perspective of the stepmother and the witch, respectively. Simon Weiland parodies the fairy tale in Leave Paradise . Hansel and Gretel also appear in Kaori Yuki's manga Ludwig Revolution . Otto Waalkes parodied the song many times, also with a fast food restaurant or as a parody of well-known hits. Reinhard Meys song Men in the DIY store (parody of Above the Clouds ) alludes to the fairy tale in the text.

Musical arrangements

- Engelbert Humperdinck : Hansel and Gretel (opera) , first performance: December 23, 1893 in Weimar

- The famous children's song Hansel and Gretel got lost in the forest was created anonymously around 1900. The parodies by Otto Waalkes and probably also Michael Ende's four-line A very short fairy tale by “Hansel and Knödel”, which ends with “Hansel took the fork and ate the dumpling”, refer to this.

Puppet show adaptation

- Piccolo puppet shows : Hansel and Gretel (with Gerd J. Pohl as puppeteer and Charles Regnier as narrator); World premiere: 1999 in Bonn

Film adaptations

The first film adaptation of Hansel and Gretel dates back to 1897; Film pioneer Oskar Messter filmed it as a silent film . Several other silent film adaptations followed, including 1921 by Hans Walter Kornblum and 1932 by Alf Zengerling . In 1940 the first of several film adaptations followed as a sound film :

- 1940: Hansel and Gretel , Germany, directed by Hubert Schonger

- 1954: Hansel and Gretel , USA, directed by Michael Myerberg and John Paul

- 1954: Hansel and Gretel , BR Germany, director: Fritz Genschow

- 1954: Hansel and Gretel , BR Germany, director: Walter Janssen

- 1971: Hansel and Gretel , Switzerland, director: Rudolf Jugert

- 1981: Hansel and Gretel - film adaptation of the opera by Humperdinck , director: August Everding

- 1987: Cannon Movie Tales: Hansel and Gretel ( Cannon Movie Tales - Hansel and Gretel ), USA, directed by Len Talan

- 1987: Ossegg or The Truth about Hansel and Gretel , BR Germany, parody of the material, director: Thees Klahn

- 1987: Gurimu Meisaku Gekijō , Japanese cartoon series, episode 2: Hansel and Gretel

- 1999: SimsalaGrimm , German cartoon series, season 1, episode 3: Hansel and Gretel

- 2006: Hansel and Gretel , Germany, fairy tale film from the ZDF series Märchenperlen , director: Anne Wild

- 2007: Hansel and Gretel - recording of Humperdinck's opera from the Dresden Semperoper , directed by Katharina Thalbach

- 2007: Hansel and Gretel - A case for the super granny , Germany / Austria, parody from the ProSieben / ORF series Die Märchenstunde

- 2007: Hansel and Gretel (헨젤 과 그레텔) , South Korean horror film 2007, directed by Pil-Sung Yim

- 2010: Hansel and Gretel - recording of Humperdinck 's opera in the Zurich Opera House

- 2012: Hansel and Gretel , Germany, fairy tale film of the 5th season from the ARD series Six in One Stroke , director: Uwe Janson

- 2013: Hansel and Gretel , USA, mockbuster from The Asylum

- 2013: Hansel and Gretel: Hexenjäger ( Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters ), USA, directed by Tommy Wirkola

- 2013: Hansel and Gretel - Black Forest ( Hansel & Gretel Get Baked ), USA, directed by Duane Journey

- 2015: Hansel and Gretel - recording of Humperdinck's opera from the Vienna State Opera , directed by Agnes Méth

- 2020: Gretel & Hansel (Gretel & Hansel) , USA, director: Oz Perkins

In the film I, Robot (with Will Smith, among others ) the story is emphasized by the “crumb for crumb” scheme, the screenwriter suggests that this fairy tale will not lose its popularity in the “future” either.

Others

- The lungwort is also known as Hansel and Gretel .

- Two houses on the Great Ring in Breslau are known as Hansel and Gretel .

- Hans and Grete were the code names of the RAF terrorists Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin .

- Hansel and Gretel is a foundation that aims to protect children from attacks, see p. Emergency island

- The city of Bergisch Gladbach named a street after Hansel and Gretel .

- In Wald bei Lüdersen ( Hanover region ) there is a Hansel and Gretel witch house.

- Hanzel and Gretyl is an American metal band.

- The gingerbread houses (also gingerbread houses or crispy houses ) of the Christmas bakery refer in their representation to the fairy tale.

- Hansel and Gretel by Lorenzo Mattotti . Implementation as a graphic narrative, Carlsen Verlag 2011, ISBN 978-3-551-51762-3 .

- The flash game Gretel and Hansel , which was published on the online portal Newgrounds , tells the fairy tale with numerous horror elements.

literature

- Brothers Grimm: Children's and Household Tales. With the original notes of the Brothers Grimm. Volume 3: Original notes, guarantees of origin, epilogue (= Universal Library 3193). With an appendix of all fairy tales and certificates of origin, not published in all editions, published by Heinz Rölleke . Reprint, revised and bibliographically supplemented edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-15-003193-1 , pp. 37-38, 448.

- Heinz Rölleke (Ed.): The oldest fairy tale collection of the Brothers Grimm. Synopsis of the handwritten original version from 1810 and the first prints from 1812 (= Bibliotheca Bodmeriana. Texts. Volume 1, ZDB -ID 750715-x ). Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cologny-Genève 1975, pp. 70-81, 355-356.

- Hans-Jörg Uther (Ed.): Ludwig Bechstein. Storybook. After the edition of 1857, text-critically revised and indexed. Diederichs, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-424-01372-2 , pp. 69-75, 382.

- Walter Scherf : Hansel and Gretel. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales . Volume 6: God and the devil on the move - Hyltén-Cavallius. de Gruyter, Berlin et al. 1990, ISBN 3-11-011763-0 , pp. 498-509.

- Hans-Jörg Uther: Handbook to the "Children's and Household Tales" by the Brothers Grimm. Origin - Effect - Interpretation. de Gruyter, Berlin et al. 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019441-8 , pp. 33-37.

- Axel Denecke : On the way to the new paradise. On the parallels between the fairy tale of "Hansel and Gretel" and the old biblical myth in the first book of Moses (Genesis) of the Bible, Chapter 3 , in: Forum, the magazine of Augustinum in the 59th year , winter 2013, Munich 2013, p 8-13.

Web links

- Goethezeitportal: Text based on Grimm and Bechstein with numerous pictures

- Märchenlexikon.de on The children with the witch AaTh 327

- Märchenatlas.de on Hansel and Gretel

- Märchenapfel.de about Hansel and Gretel

- Heinrich Tischner to Hansel and Gretel

- Interpretation by Daniela Tax on Hansel and Gretel

- SurLaLuneFairyTales.com: Illustrations, text versions and interpretations of Hansel and Gretel

- Illustrations

- Hansel and Gretel as mp3 audio book on LibriVox

- ARD-Alpha : Hansel and Gretel tells about Michael Köhlmeier in the show Köhlmeier's fairy tales

Individual evidence

- ↑ Original quote from the Brothers Grimm, identical text in the editions of KHM 1812, 1819, 1837, 1840, 1843, 1850 and 1857, Hansel and Gretel on Wikisource. See also “Last Hand Edition” from 1857, Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart 2007, p. 104.

- ↑ Original quote from Ludwig Bechstein: Complete fairy tales. 1983, p. 62, see also, for example, the text print in the Goethezeitportal .

- ^ Bechstein: Complete fairy tales. 1983, p. 62.

- ↑ Brothers Grimm. Children's and Household Tales. With the original notes of the Brothers Grimm. Volume 3. 1994, pp. 37-38, 448.

- ↑ Rölleke (ed.): The oldest collection of fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. 1975, pp. 70-81.

- ↑ Uther: Handbook on the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm. 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Scherf: Hansel and Gretel. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 6. 1990, p. 500.

- ↑ Uther: Handbook on the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm. 2008, p. 34.

- ↑ Appendix with comments on the German book of fairy tales by Ludwig Bechstein, p. 786 f.

- ↑ See Hans and Grete in the Traubüchlein (1529) by Martin Luther or the Cologne saga by Jan and Griet .

- ^ Hans-Jörg Uther (Ed.): Ludwig Bechstein. Storybook. After the edition of 1857, text-critically revised and indexed. Diederichs, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-424-01372-2 , p. 382.

- ^ Rudolf Meyer: The wisdom of German folk tales. Urachhaus, Stuttgart 1963, pp. 91-95.

- ↑ Hedwig von Beit: Symbolism of the fairy tale. 1952, pp. 133-135.

- ↑ Bruno Bettelheim: Children need fairy tales. 31st edition 2012. dtv, Munich 1980, ISBN 978-3-423-35028-0 , pp. 183-191.

- ^ Friedel Lenz: Visual language of fairy tales. 8th edition. Free Spirit Life and Urachhaus publishing house, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-87838-148-4 , pp. 55-65.

- ↑ Ortrud Stumpfe: The symbolic language of fairy tales. 7th, improved and enlarged edition. Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Münster 1992, ISBN 3-402-03474-3 , p. 211.

- ↑ Frederik Hetmann: dream face and magic trace. Fairy tale research, fairy tale studies, fairy tale discussion. With contributions by Marie-Louise von Franz, Sigrid Früh and Wolfdietrich Siegmund. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-596-22850-6 , p. 123.

- ↑ Johannes Wilkes: Fairy tales and psychotherapy. In: Kurt Franz (Ed.): Märchenwelten. The folk tale from the point of view of various specialist disciplines. 2003.

- ↑ Eugen Drewermann: The exhausted soul - of the opportunities and fate of depression. Seminar 7.-8. March 2008, Nuremberg, Auditorium, CD 1/4.

- ↑ Drewermann, Eugen: Landscapes of the Soul or How to Overcome Fear Grimm's fairy tales interpreted in depth psychology, Patmos Verlag, 2015, pp. 49–82

- ↑ Herbert Pfeiffer: The environment of the small child and his medicine. In: Uwe Reuter, Ralf Oettmeier (Hrsg.): The interaction of homeopathy and the environment. 146th Annual Meeting of the German Central Association of Homeopathic Doctors. Erfurt 1995, pp. 53-56 .; Martin Bomhardt: Symbolic Materia Medica. 3. Edition. Verlag Homeopathie + Symbol, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-9804662-3-X , p. 878 .; Karl-Josef Müller: Wissmut. Materia Medica Müller 5.0. Zweibrücken 2016, ISBN 978-3-934087-34-7 , p. 408.

- ^ Wilhelm Salber : Märchenanalyse (= Wilhelm Salber: Werkausgabe. Volume 12). 2nd, expanded edition. Bouvier, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-416-02899-6 , pp. 53, 95-97.

- ↑ How is fear? In: Die Zeit , January 10, 2019, No. 3, p. 40.

- ↑ Roland Lebl: Once upon a time ... In: Wolfgang Mieder (Hrsg.): Grimmige Märchen. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 91-93 (first published in: Simplicissimus. No. 12, March 21, 1959, p. 182; author's information “Lebl, Roland” at Bodice marked with "?".).

- ↑ 1963. Newer edition: Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2002. Latest edition: Reclam, Stuttgart 2007. ("Traxler's book parodies investigative science journalism.")

- ↑ Paul Maar: The tattooed dog. Süddeutsche Zeitung Verlag, Munich 1967.

- ^ Julius Neff: Hansl & Gretl. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 99–101 (first published in: Ludwig Merkle (Ed.): Gans, du hast den fuchs. Funny things for children. Fischer, Frankfurt 1969, pp. 32–33; Julius Neff, according to Mieder, pseudonym of Ludwig Merkle).

- ↑ Iring Fetscher: Who kissed Sleeping Beauty awake? The fairy tale confusion book. Fischer, Frankfurt a. M. 1974.

- ↑ Dispute over "Hansel and Gretel". Edler von Goldeck reports from the third International Fairy Tale Congress in Oil Lake City, Texas (1975). In: Iring Fetscher: The Gnome Men’s Zero Tariff. Fairy tales and other confusing games. Fischer, Frankfurt a. M. 1984.

- ↑ Karin Struck: Memories of Hansel and Gretel. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 94–98 (first published in: Jochen Jung (Hrsg.): Bilderbogengeschichten. Fairy tales, sagas, adventures. Newly told by authors of our time. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1976, pp. 203-206.).

- ^ Josef Wittmann: Hansel and Gretel. In: Johannes Barth (ed.): Texts and materials for teaching. Grimm's fairy tales - modern. Prose, poems, caricatures. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-015065-8 , p. 44 (1976; first published in: Hans-Joachim Gelberg (Ed.): Neues vom Rumpelstiltskin and other house fairy tales by 43 authors . Beltz & Gelberg , Weinheim / Basel 1976, p. 196.).

- ↑ Wolfgang Sembdner: Alphabetically. In: Johannes Barth (ed.): Texts and materials for teaching. Grimm's fairy tales - modern. Prose, poems, caricatures. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-015065-8 , pp. 44-49 (1977; first published in: Wolfgang Sembdner: Grimmskrams. Parodistische Hänseleien. Nürnberg 1981, p. 5.).

- ^ Fritz Vahle: Hansel and Gretel. In: Johannes Barth (ed.): Texts and materials for teaching. Grimm's fairy tales - modern. Prose, poems, caricatures. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-015065-8 , p. 46 (1986; first published in: Fritz Vahle: Märchen. Adjusted to the time and put in verse. Justus von Liebig, Darmstadt, p. 10.) .

- ↑ Wolfgang Sembdner: poet forest. In: Johannes Barth (ed.): Texts and materials for teaching. Grimm's fairy tales - modern. Prose, poems, caricatures. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-015065-8 , p. 45 (1977; first published in: Wolfgang Sembdner: Grimmskrams. Parodistische Hänseleien. Nürnberg 1981, p. 11.).

- ↑ Josef Reding: Remnants of a message from yesterday. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 102-108 (first published in: Josef Reding (Ed.): Schonzeit für Pappkameraden. Bitter, Recklinghausen 1977, pp. 52-57. ).

- ↑ Dieter Harder: Hanselus Gretulaque. In: The ancient language teaching. 29, 4/1986, p. 70.

- ^ Rudolf Otto Wiemer: Hansel and Gretel or: The right grandmother. In: Johannes Barth (ed.): Texts and materials for teaching. Grimm's fairy tales - modern. Prose, poems, caricatures. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-015065-8 , pp. 47–54 (1987; first published in: Rudolf Otto Wiemer: Der dreifältige Baum. Waldgeschichten. Quell, Stuttgart 1987, pp. 182–190.) .

- ↑ Beate Mitzscherlich: Taken away. Ulla Hahn: Dear Lucifera. In: Die Horen. Volume 1/52, No. 225, 2007, ISSN 0018-4942 , pp. 8, 205-210.

- ↑ simon-weiland.de

- ↑ Hansel and Gretel - The Opera by E. Humperdinck ( Memento from December 2, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ www.piccolo-puppenspiele.de

- ↑ Hansel and Gretel - silent film from 1897

- ↑ Hansel and Gretel - silent film from 1921