The virtuoso

The virtuoso is a picture story published in 1865 by the humorous draftsman and poet Wilhelm Busch , which is considered to be one of the most innovative illustrations in his work. It is one of the reasons why Wilhelm Busch was increasingly given the honorable nickname of the grandfather of comics or the forefather of comics from the second half of the 20th century .

The virtuoso did not appear as an independent printed work like the great picture stories of Busch such as Die pious Helene or St. Antonius von Padua , but as an illustration in the Fliegende Blätter published by the Munich publishing house Braun & Schneider , which in the same year also acquired the rights to Wilhelm Busch's picture story Max and Moritz acquired.

content

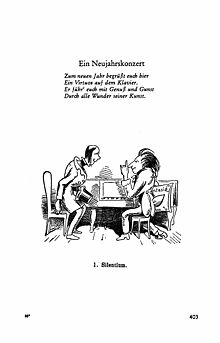

The virtuoso is the story of a pianist who gives a private concert to an enthusiastic listener for the New Year. The satire differs in several respects from the other works of Wilhelm Busch.

Busch's picture stories usually follow a course of action that begins with a description of the circumstances from which the conflict arises, then increases the conflict and finally brings it to its resolution. The virtuoso deviates slightly from this scheme. In the satire on self-portrayal artist attitude and their exaggerated admiration, the introduction is limited to four short lines:

- Welcome to the New Year here

- A virtuoso on the piano

- He guides you with pleasure and grace

- Through all the wonders of his art.

The following individual scenes are not annotated with bound texts, but are only titled with terms from musical terminology such as Introduzione , Maestoso or Fortissimo Vivacissimo . Wilhelm Busch invented some of these terms , for example the Fuga del diavolo ("Devil's Fugue "). The scenes increase in tempo from the initial Silentium to the penultimate finale furioso , which ends with a kind of bravo-bravissimo . Every part of the body and every piece of clothing is included in this increase. The pianist's handkerchief, which is peeking out from between the tails, points with its tip sometimes to the left, sometimes to the right, becomes a curl or turns into a spiral. Finally, the penultimate scenes become a simultaneous display of several phases of movement of the pianist, and the notes dissolve into notes dancing over the grand piano.

What is particularly striking is Wilhelm Busch's ability to transform linguistic into graphic images. The enthusiastic listener gets literally “sticky eyes” next to the piano, he becomes all eyes and ears , so that his head consists only of a giant ear and eye .

Origin context

Kaspar Braun , one of the two founders of the Braun & Schneider publishing house, employed a number of art students in his publishing house, who created illustrations for the publishing program for a one-off fee. He became aware of Wilhelm Busch through his contributions to the journal of the artists' association Jung München .

When Wilhelm Busch started to work for Kaspar Braun, he was in a financially difficult position. He broke off his mechanical engineering studies in Hanover shortly before the end of it, in Düsseldorf and Antwerp he had enrolled at the art academies, but each stayed for less than a year. After suffering from severe typhoid fever, he had lived in his parents' house in Wiedensahl for a few months and then confronted his middle-class parents with the desire to continue his art studies in Munich. He was then adopted by his father in Munich in 1854 with a final payment. His expectations of studying art were not fulfilled in Munich either. For four years Wilhelm Busch let himself drift seemingly without a plan. During this time he had completely broken off contact with his parents, he only visited his uncle, Pastor Georg Kleine, several times in Lüthorst . It is not known what Wilhelm Busch used to make a living from during this period.

The work for Kaspar Braun began in the second half of the 1850s. Wilhelm Busch first made drawings for given texts. If they liked, Wilhelm Busch transferred the story for printing on a boxwood panel. This was then processed by wood engravers and printed. The first larger picture stories, which also appeared in the newspapers of the publishing house Braun & Schneider , were The little honey thieves and The little painter with the big folder . The latter story corresponds in its way of drawing strongly to the later work of Wilhelm Busch. The little honey thieves with their detailed interior drawing are reminiscent of illustrations by Moritz von Schwind and Ludwig Richter , at least in terms of the drawing technique .

The virtuoso falls into the late phase of Wilhelm Busch's collaboration with the Braun & Schneider publishing house. Wilhelm Busch found the dependence on the Braun & Schneider publishing house and its assertive director Kaspar Braun increasingly depressing. For the publication of the picture antics , his first independent work, he had already looked for a new publisher in Heinrich Richter, the son of the Saxon painter and draftsman Ludwig Richter . When he began to work on his next larger picture story Max and Moritz in 1863 , Wilhelm Busch saw himself as an independent book author. Heinrich Richter had at the four illustrated stories (u. A. Krischan with Piepe and The Eispeter ), from which the 1864 published images antics , doubts existed from the beginning. They were neither fairy tales nor children's books, and far surpassed the contemporary Struwwelpeter in their cruelty. Heinrich Richter's skepticism was justified. The book sold extremely poorly and was largely unsuccessful in the 1864 Christmas business. Heinrich Richter therefore refused to publish Wilhelm Busch's next picture story, the story of Max and Moritz , in January 1865 . Wilhelm Busch contacted his old publisher Kaspar Braun again on February 5, 1865, although he had not had any contact with him for a long time. In February, Kaspar Braun promised him the publication of Max and Moritz . For the rights to this picture story, Kaspar Braun paid Wilhelm Busch only a one-off amount, which at 10,000 gold marks, however, corresponded to the two-year wage of a craftsman. In August 1865, Wilhelm Busch transferred the preliminary drawing to the boxwoods, and with that the collaboration with the publisher ended.

The picture story as anticipation of comics and cartoons

Busch's virtuoso combination of words and images anticipates comics and cartoons . Transforming every event into destruction, disorder and chaos in a dramatic and comic way is a common basic principle of Busch's graphic work and the development of comics and cartoons. Andreas C. Knigge therefore describes Wilhelm Busch as the “first virtuoso” of picture narration.

Even his early picture stories differ from those of his colleagues who also worked for Kaspar Braun. His pictures show an increasing concentration on the main characters, are more economical in the interior drawing and less fragmented in the ambience. The punch line develops from a dramaturgical understanding of the entire story. The plot is broken down into individual situations like in a film. In this way, Busch gives the impression of movement and action, sometimes reinforced by a change of perspective. According to Gert Ueding , the representation of movement that Busch succeeds in despite the limitation of the medium has so far remained unmatched.

Fine artists were inspired by The Virtuoso well into the 20th century . August Macke even stated in a letter to his gallery owner Herwarth Walden that he thought the term futurism for the avant-garde art movement that emerged in Italy at the beginning of the 20th century to be a mistake, since Wilhelm Busch was already a futurist who insisted on time and movement Image banned.

Comparable work in Wilhelm Busch's work

Individual scenes in the pictures for the Jobsiade , which Wilhelm Busch published in Bassermann Verlag in 1872, are similarly forward-looking as individual scenes by the virtuoso . At Jobs' theological exam, twelve clergymen in white wigs sit opposite him. Your examinee answers her questions, which are by no means difficult, so stupidly that every answer triggers a synchronous shake of the head of the examiners. The wigs start to move indignantly, and the scene becomes a movement study that is reminiscent of Eadweard Muybridge 's phased photographs . Muybridge had begun his movement studies in 1872, but did not publish them until 1893, so that this smooth transition from drawing to cinematography is also a pioneering artistic achievement by Busch.

supporting documents

literature

- Michaela Diers: Wilhelm Busch, life and work. dtv 2008, ISBN 978-3-423-34452-4 .

- Joseph Kraus: Wilhelm Busch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1970, ISBN 3-499-50163-5 .

- Gudrun Schury: I wish I were an Eskimo. The life of Wilhelm Busch. Biography . Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-351-02653-0 .

- Gert Ueding : Wilhelm Busch. The 19th century in miniature. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1977.

- Eva Weissweiler: Wilhelm Busch. The laughing pessimist. A biography . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-462-03930-6 .

Single receipts

- ↑ Daniel Ruby: Scheme and Variation - Investigations on Wilhelm Busch's picture stories . European university publications, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-631-49725-3 , p. 26.

- ↑ Weissweiler, p. 142 and p. 143.

- ↑ a b Schury, p. 81.

- ↑ Andreas C. Knigge : Comics - From mass paper to multimedia adventure. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, 1996, p. 14.

- ↑ Schury, p. 80.

- ↑ Ueding, p. 193. Ueding incorrectly describes the graphic technique used by Wilhelm Busch as woodcut .

- ↑ Ueding, p. 196.

- ↑ Weissweiler, p. 143 and p. 144.

- ↑ Weissweiler, p. 204 and p. 205.