Kynocephalic

Kynokephale ( Greek κυνοκέφαλοι Kynoképhaloi ), composed of ancient Greek κύων kýon “dog” and κεφαλή kephalḗ “head”, denotes dog-headed mythical creatures that have appeared in literature and art since antiquity and that met with great interest in the Middle Ages. They belong to the monstrous fabulous peoples that one imagined on the fringes of ecumenism (the civilized world), especially in India or Africa. To what extent there was a belief in their real existence is difficult to determine.

The dog-headed human idea seems to be spread all over the world. Some scientists already suspect their origin in early myths in which they appear as chthonic demons.

The cynocephalic are numerous in the literature. Around 700 BC Hesiod calls monstra , including Hemikynes (half- dogs ). One of the first detailed descriptions comes from Ktesias von Knidos , who drew from Persian and Indian sources.

description

Exterior

Kynokephale have a human figure, but can have other dog features in addition to their dog's head, such as fur or claws. In contrast, in early texts they only wrap themselves in animal skins.

Culture

In the ancient and medieval sources, Cynokephale, like other peoples, are usually only very briefly described. Concrete information about their culture is therefore rare. The inability to speak, which can be explained by the non-human head, is often described. Ktesias describes the dog-headed people as a peaceful people who also trade with other peoples. Accordingly, communication with the dog-headed should be possible. The description of the religion of these mythical creatures appears several times, but no more detailed information is given. Jean de Mandeville, for example, portrays the Cynocephalic people as a particularly god-fearing people. In addition to the notion of the linguistic, god-fearing and trading dog-heads, they could also be understood as dangerous enemies. This is shown by a mention of bloodthirsty cynocephalies in the Historia gentis Langobardorum of Paulus Deacon . Further early evidence can be found in Strabon , Plutarch and Aelian . Strabon mentions Kynokephaloi as a legendary tribe of Ethiopians. Plutarch and Aelian report on a dog king who rules the Ethiopians. Pliny also names this king , in addition to the Kynocephalic he also knows Kynomolgi with dog heads. The differences between the two peoples are not made clear. The dog-headed characters are also mentioned in the history of the Diocese of Hamburg, which Adam von Bremen wrote around 1075. They are described here as the men of a people who live among the Amazons .

nutrition

There is disagreement about the diet of the dog-headed people. According to the Alexander novel, they only eat fish. Another variant shows a manuscript from the British Library in London . The dog-headed man pictured there seems to be eating from the leaves of a tree. In connection with the question of nutrition, other mythical creatures, the cynomolgi , are also referred to in the research literature . John Block Friedman and Michael Herkenhoff believe that this was initially a variant of the cynocephalic, which later, at least in some sources, appears as a separate breed because it was no longer properly understood. In Pliny they milk dogs and drink their milk, whereas in later sources they are shown as anthropophages .

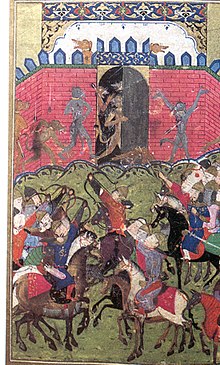

Kynokephale in Art

Zajadacz-Hastenrath gives a number of examples of Kynokephale in illumination . There are also dog-headed elements in architectural ornamentation , especially in Romanesque and Gothic styles. The tympanum of Sainte Marie-Madeleine in Vézelay is an important example . The cynocephalic occupies a prominent position next to the head of Christ and are therefore not to be understood as demons , but as a people to whom the Christian faith is to be brought by the apostles sent out. A dog-headed man is also depicted in the rose window of the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Lausanne , along with other wonderful people . It is labeled cinomolgi , but is currently consuming a human leg. The inhabitants of this window on the edge of the earth are shown next to the Paradise Rivers and thus represent exotic regions. The cynocephalic in the churches of St. Jakob in Kastelaz , St. Margareth in Lana and St. Martin in Zillis are optically out of line . The first two have fins instead of feet or claws, the latter even has a double-tailed fish body, which is usually only found in sirens .

Kynokephale in the Southeast European tradition

In the folk tales, especially of the Slovenes and Croats, even as far as Carinthia, the dog-headed ( Pesoglavci ) can still be found today. The consensus of these stories shows the image of a cruel ogre who is particularly after Christians or women. The dog heads are more or less intelligent; often they appear in the role of outwitted robbers. Visually, the dog-headed people from the east are sometimes somewhat different from their Western European relatives. Common traits are buck or horse legs, one-eyed and one-legged. It is also noticeable that the Pesoglavci live in nearby forests.

Kynokephale in Australia

In stories from the dream time of the Australian natives there are also dog-headed people who, depending on the story, either created humans, are responsible for their creation or are the ancestors of the Australian natives living today. The idea of a dog-headed human being as the ancestor of today's humans was also carried over to dogs in general. In such ideas, the Australian natives are descended from dingoes and people of other origins from the corresponding dogs in their areas.

Interpretations

The associations with dog heads are closely related to those with dogs in general. The ancient and medieval associations with dogs are very different, but a tendency towards the negative is unmistakable. Cynokephale can appear as harbingers of hell and hosts of the Antichrist.

In the Middle Ages, the cynocephalic were seen as demonic hell beings, but also as a symbol of the possibility of converting even an extremely uncivilized people. That they can stand as an example of the conversion of the people on the edge of the earth is shown in addition to the depictions in Vézelay and Saint-Étienne in Auxerre, as well as the Pentecostal images from the Eastern European tradition, in which they appear as people to be evangelized by the apostles. The mission is also clearly represented in the Theodor Psalter from the 11th century, where Christ himself teaches dog-headed people. This role of the cynocephalic arises from several sources, namely the Christophorus or Christianus legend and the story about the apostles Bartholomäus and Thomas .

Friedman also describes the legend of St. Mercury , who proselytized Cynokephale, who then stood by his side as helpers. However, this legend is not very widespread in the West and only appears in sacred art in Egypt. In addition to the positive interpretation that the story of the converted cynocephalic had spread in the Christian West, there is the interpretation of the Gesta Romanorum , which compares the cynocephalic with preachers.

This is in contrast to the interpretation of Thomas von Cantimpré , who understands the cynocephalic as a symbol of defamation because of their inarticulate barking.

As with other animal-human hybrid beings, attempts have often been made to find the starting point for the creation of legends in reports on exotic animal species. Ursula Düriegel suspects that cynocephaly are to be equated with baboons . Already medieval authors brought cynocephaly with apes in conjunction. It is uncertain whether the myth of the cynocephaly can actually be traced back to monkeys or whether the monkeys were only (mis) understood as cynocephalic and thus perhaps later changed the image of this being. Kretzenbacher also suggests the demonization of a being from Pagan mythology. There may be a connection with the dog or jackal-headed deities of Egypt ( Upuaut , Anubis ). In the Middle Ages, the cynocephalic is a popular example in anthropological discussions about the definition of humans and their differentiation from animals. Isidore von Sevilla thinks that one should classify the cynocephalic as animals because of their barking.

See also

literature

- John Block Friedman: The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA et al. 1981, ISBN 0-674-58652-2 .

- Leopold Kretzenbacher : Kynokephale demons of southeast European folk poetry. Comparative studies on myths, legends, mask customs around Kynokephaloi, werewolves and South Slavic Pesoglavci (= contributions to knowledge of Southeast Europe and the Near East. Vol. 5, ZDB -ID 1072151-4 ). Trofenik, Munich 1968.

- Walter Loeschke: Sanctus Christophorus canineus. In: Georg Rohde et al. (Ed.): Edwin Redslob on his 70th birthday. A festival. Blaschker, Berlin 1955, pp. 33-82.

- David Gordon White : Myths of the Dog-Man. University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL et al. 1991, ISBN 0-226-89508-4 .

- Rudolf Wittkower : Marvels of the East. A Study in the History of Monsters. In: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institute. Vol. 5, 1942, ISSN 0959-2024 , pp. 159–197 (Also in: Rudolf Wittkower: Allegory and the Migration of Symbols. Thames and Hudson, London 1977, ISBN 0-500-27470-3 , pp. 45– 75; in German: Die Wunder des Ostens: A contribution to the history of the monsters. In: Rudolf Wittkower: Allegory and the change of symbols in antiquity and renaissance. DuMont-Literatur-und-Kunst-Verlag, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3- 8321-7233-5 , pp. 87-150).

- Salome Zajadacz-Hastenrath: Mythical creatures . In: Otto Schmitt (Ed.): Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte . , Volume 6: Donkey Back - Color, Colorants. 61. Delivery, 1971. Printmüller, Munich 1968–1973, Sp. 739–815.

Web links

- Article in Theoi Lexicon

- Anthony Weir: A holy dog and a dog-headed saint .

- Sophia Menache: Dogs: God's worst enemies?

- The Cryptid Zoo: Cynocephali

Individual evidence

- ↑ Under the entry cynocephal * alone there are 111 individual specimens in the Patrologia Latina Database - Zajadacz-Hastenrath (column 766) mentions other names: cenocephales, cinomolgi, cynopenes, cynoprosopi, canicipites, equinocophali.

- ^ For example, Wittkower p. 91; Kretzenbacher p. 30

- ↑ On the claws and the covering in animal skins. Lucidarius (I.53)

- ↑ Acephale or skiapods, for example

- ↑ For example Konrad von Megenberg Book of Nature (VIII.3), Lucidarius (I.53)

- ↑ Plutarch , De comunibus notitiis, chap. 16; Aelian , De natura animalium VII, 40.

- ↑ Pliny , Naturalis historia 6,35,192.

- ↑ Pliny, Naturalis historia VI, 190 and VII, 31. Cf. on this the Cynomolgi at the Notre-Dame Cathedral (Lausanne) and in Marco Polo , chap. CLXXIII.

- ↑ For example at the churches of Notre Dame de Cunault , the church in Fleury-la-Montagne , the parish church of Saint-Nicolas de Maillezais and Ols Kirke in Olsker .

- ^ Similar in a window in the Saint-Etienne cathedral in Auxerre .

- ↑ Localized among others in St. Jakob im Rosental. They are connected to the Turkish attacks of the 15th century, but seem to be older overall. It would be interesting to compare the legends with the frescoes in Tyrol, among other places.

- ↑ See Kretzenbacher .

- ↑ Deborah Bird Rose: Dingo makes us Human, life and land in an Aboriginal Australian culture . Cambridge University Press, New York, Oakleigh 1992, ISBN 0-521-39269-1 .

- ^ So in the tympanum of the Saint-Pierre church in Beaulieu-sur-Dordogne .

- ↑ Fig. In Friedman, p. 66.

- ↑ London, British Library, Ms. Gr. Add. 19352, fol. 23r (11th century).

- ↑ Cf. Ellen Beer : The rose of the cathedral of Lausanne and the cosmological circle of images of the Middle Ages . Second part. (Dissertation Bern 1950) Bern 1952. p. 25 (With an impression of a manuscript from the 14th century) and Wittkower p. 112.

- ↑ Ursula Düriegel: The mythical creatures of St. Jakob in Kastelaz near Tramin. Romanesque imagery of ancient and pre-ancient origins. Böhlau, Vienna et al. 2003, ISBN 3-205-77039-0 , p. 63; so also Friedman p. 24f.

- ↑ For example Solinus Collectanea rerum mirabilum (27,58), Albertus Magnus , De animalibus 26, 2,1,4, Isidor von Sevilla, Etymologiae 12,2,32, also in the texts of the Ebstorf world map .

- ↑ See the work of Carl Albrecht Bernoulli and Zofia Ameisenowa.

- ↑ Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae 11: 3, 15.