Utopia

A utopia is the design of a possible, future, but mostly fictitious way of life or social order that is not tied to contemporary historical and cultural framework conditions.

The term is derived from ancient Greek οὐ ou “not” and τόπος tópos “place, place”, together “not place”. The fictional social orders described in utopias result from a critique of the respective contemporary social order and can be read as positive counter-drafts. With Thomas More , the founder of the genre, the term is a language game between utopia and eutopia from εὖ (eu) "good" and τόπος . In contrast, dystopia describes the pessimistic description of an unethically negative social order.

In everyday linguistic usage, utopia (especially as an adjective utopian ) is used as a synonym for a vision of the future that the predominant social groups consider to be a beautiful, but impracticable, vision of the future.

With regard to their feasibility, a distinction is made between descriptive (apparently describing future trends), evasive (associated with the tendency to flee from the world ) and constructive (to be actively realized) utopias. These can relate to forms of government and economy, the future of culture, art or religion, different types of coexistence, innovations in education or gender constellations, etc. a. Respectively.

Origin and content of the term

The term comes from the title De optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia (From the best state of the state or from the new island of Utopia) of the 1516 novel by the English statesman Thomas More , who describes an ideal society with which he helped his contemporaries holds up a critical mirror.

Often one also comes across the simplified term Utopia , which actually only describes the island on which the members of the ideal society live. Thomas More's utopia is not in the future, but in a distant part of the world; The ideal community is not realized within the framework of the Christian order of salvation, but within the world.

It was not until the 18th century that utopia ( Reinhart Koselleck ) became temporal. In today's linguistic usage, a utopia is almost always located in the future and rarely in the past or the spatial distance.

It is characteristic in all cases that existing approaches are taken further in the present or conditions are questioned. In the first part of his work, Thomas More criticized the social conditions in England of his time. Thus utopias usually have a socially critical character,

- either by claiming that a better society is possible (see Thomas More Utopia, Heinrich von Kleist The Earthquake in Chili ("The Valley of the Righteous"), Burrhus Frederic Skinner Walden Two )

- Or vice versa, by mentally developing existing tendencies, turning them into dystopias , i.e. pessimistic negative utopias, and thus sharply criticizing them, as in classic novels and satires such as Brave New World ( Aldous Huxley ) and 1984 ( George Orwell ), in visions of the cyberpunk genre and films like … year 2022… who want to survive (Soylent Green) .

The main content of a utopia is often a social vision in which people practically live an alternative social system (example: New Harmony ). Utopia is often presented in literary form ( utopian novel ), through cinematic works or in works of art.

Although the term utopia is traditionally used as a synonym for optimistic-fantastic ideals, utopia in its socio-critical aspect can be interpreted in a practical and contemporary way: Proponents see new possibilities looming on the horizon . Critics deny that they can be realized and warn of undesirable or careless possible consequences.

feasibility

A utopia is characterized by the fact that it is not immediately realizable at the time of its creation. This impossibility of rapid implementation is always due to one (or more) of the following reasons:

- The utopia is technically not feasible, i. In other words, it is recognized that the technical possibilities are far from being that advanced, or it is asserted that even in the distant future they will never be sufficiently advanced to be able to do justice to the circumstances depicted in the utopia (see George Orwell , 1984 and also Werner von Siemens , On the Age of Science ).

- The realization is not wanted by a majority or power elite or is rejected as undesirable.

- In the case of an (exaggerated) counter-image to the social reality of the present, it must also be considered that a realization of the utopia is not wanted by the author. The attempt at a realization would then be a tragic misinterpretation of his - possibly ironic - intention (see e.g. More ' Utopia ).

Tragedy of unrealisability

The tragedy of the long work that has to be done to make utopian ideas a reality in the far distance is an elementary aspect of utopia. What is tragic is that - both on the fictional level and in attempts to implement a utopia politically - the intention of social improvement can easily be transformed into its opposite.

Attempts to implement utopian designs by force almost inevitably lead to a deterioration in the social situation (lack of freedom, war, hatred). However, since many utopian designs are essentially based on a totalitarian form of government, they can hardly tolerate deviations and are therefore prone to violence. Concrete utopia, on the other hand, is based on the given possibility of realization .

Because utopias can only be understood as unrealistic from their respective historical context, some aspects of everyday life at the beginning of the 21st century already compensate for technical and social utopias from the 1950s ( internet , space travel ) or even surpass them ( genetic engineering ). Elements of dystopias ( Big Brother ) can also be found ( surveillance ).

Drive for realization

Robert Jungk saw utopias as a drive for social inventions in a desirable future. He advocated a democratization of utopian thinking by promoting the imagination and understood this as a political means not to sink into passivity and resignation in the face of social crises . The future workshop concept he developed includes a utopian phase .

Different kinds of utopias

Utopias can emerge across all media. Although they are often associated with the medium of literature (cf. Utopian literature ), utopian intentions can also be found in art (e.g. Wenzel Hablik's Great Colorful Utopian Buildings ), in architecture (e.g. Filaretes Plan of the ideal state of Sforzinda ; see also Utopian Revolutionary Architecture ), in film (e.g. Fritz Lang's Metropolis ) or in video games (e.g. Bethesda Softworks ' Fallout 3 , or the " Bioshock " series). Ernst Bloch (Concrete Utopia) and Theodor W. Adorno even assume that the utopian intention is a deeply human characteristic that, regardless of the situation in life, simply belongs to people. Hence, utopias can be found again in any form of cultural expression.

Thematically, there are utopian ideas in every area, u. a. So in the technical, social, cultural and religious area. In practice, however, they also represent mixed forms (e.g. technocracy ). In dystopias, for example, end-time scenarios often form the narrative space for the actual (often anarchic or totalitarian) social designs.

Political utopias

Political utopias, as they were first drafted in Plato's Politeia in the form of the idea of a class-hierarchically ordered ideal state, are characterized by the fact that they comprehensively criticize the socio-economic conditions and institutions that existed in their time and, based on their criticism, create a fictitious, in design a comprehensible alternative. This distinguishes utopias from chiliasms and myths.

According to Richard Saage, two fundamental social-state orientations can be identified in the history of political utopias : They move between the ideal types of state-centered designs on the one hand and anarchist construction principles on the other. An example of an etatist utopia is Tommaso Campanella's La città del Sole (The Sun State), which is technocratically controlled based on the model of the Spanish monarchy .

What the political utopias have in common from the early modern period to the late 20th century is that they criticize injustice, inequality and oppression. Which institutions are proposed to ensure a better and more just society changes in the history of political utopias. The contradicting relationship between equality and freedom often forms the basis of political utopias, but is conceptually developed in opposing ways in authoritarian-state-centered and anarchist utopias. Richard Saage assumes that after 1989 the authoritarian-statist line of utopian thinking came to an end. But one still needs utopias to solve the problems of the 21st century.

With the ideology of the Islamic State (IS) , a new form of totalitarian, but non-statist political-religious utopias has emerged recently.

Social utopias

Thomas More had given the dream of a return to paradise the name Utopia and thus inspired the belief of progress in a better future. He made the earliest recorded plea for freedom of parliamentary speech and freedom of conscience. Such belief in progress also fed the Enlightenment social utopias of the 18th century, the science-driven utopias of the 19th and the technologically driven futuristic utopias of the 20th century.

Socialist and communist utopias prefer to deal with the end of exploitation and the redistribution of goods in favor of the economically weaker (“from top to bottom”), often with simultaneous abolition of money (“each according to his needs”). Sometimes they develop ideas of abolishing economically determined wage labor (see Paul Lafargue , “ The Right to Laziness ”). The citizens only pursue such work that corresponds to their self-realization . They have a lot of time to cultivate the arts and sciences (see also utopian socialism ).

After the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the socialist world of states, neoliberal ideologies that had already been conceived by Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig Mises before the global economic crisis of the 1930s spread . In these ideologies, the concept of a society is abandoned to such an extent that no independent sphere of a society that is separate from the economy is recognizable. Society is, as it were, absorbed by the market . The core of the market is seen in the price mechanism, even if it is unclear whether this mechanism actually works in reality or whether it has fundamental flaws. If the market is not hindered, the neoliberal utopia will be fully realized; then the politics that must now obey the market no longer prevail; the consumers are the real sovereign. “Market” and “socialism” are stereotypically contrasted with one another. According to Hayek, the starting point of the new order is the individuals with their subjective plans. Your subjective knowledge does not have to be coordinated by anyone, especially not by politicians or a planning authority. Only the market provides an efficient mechanism for using this dispersed information. Hayek ascribes an “over-rationality” to the market: the market rules over everyone like God. His signals (the prices) are givers of command that control the actions of people, and these have to adapt to something higher that they do not understand. "The narrative of 'the market' as a quasi-god implies an (eschatological) 'end of history'". Besides the godlike market, there must be no other god relevant to society and no other utopias for shaping society. Every idea like “social justice” is an illusion for Hayek: people cannot consciously choose which direction they want to take. This utopia is also followed by the end of the story claimed by Francis Fukuyama .

Just as the Great Depression and the subsequent authoritarian and fascist regimes destroyed Hayek's utopia of a market-driven world without society and politics, the neoliberal utopias of the 1980s and 1990s were considerably disrupted by the consequences of globalization . Increasing financial and debt crises, unemployment and impoverishment of the middle classes in developed countries, widespread insecurity and involuntary waves of migration raised doubts about a market-driven world without political intervention. The gains in freedom turned out to be dearly paid for. After the failure of both the socialist and the neoliberal utopias had proven itself within 20 years, dystopias such as the scenarios of a climate catastrophe increased.

In his last, posthumously published work, Retrotopia, Zygmunt Bauman speaks of the spread of social retrotopias that no longer have their vanishing point in an idyllic future, but in the idealized past. Characteristic of them are the transfiguration of the past and the longing for continuity in a world fragmented by neoliberalism, in which the individual is progressing towards the desolidarization, liberation and lack of ties. The retrotopias feed on the longing for the lost, stolen, "undead" past. Bauman emphasizes as the main cause the sharp increase in violence in the hyperglobalized world, which is reminiscent of that of Thomas Hobbes . The people are no longer willing to pay for gains in freedom through a loss of security, as the liberal elites are demanding. They are increasingly differentiating themselves and reflecting on their national, ethnic, religious, etc. identities at the “tribal fire”. The result is increasing aggressiveness against others, strangers and those seeking protection.

Religious utopias

Most of the Christian ideas of the paradise or garden of Eden on earth, the established kingdom of God , cannot be called utopia. Although they denote an ideal dream for the future, they are achieved through God's grace (and, depending on the theological or denominational orientation, through human cooperation). Above all, however, the theological statement that with the descent of Jesus Christ, the incarnation of Jesus, the kingdom of God had already begun, is an explicitly non-utopian one.

The Christian conception of the future is therefore not purely future-oriented, but denotes a simultaneous “already” and “not yet”: the kingdom of God has already begun with Jesus Christ, will be continued in the church and has already been established in heaven. In the whole world, however, this idea is not yet accepted and is therefore still waiting for completion. Accordingly, no new world is preached, but the renewal of the old world. This concept is referred to in a clear demarcation to the utopia as eschatology .

However, utopian currents are certainly present in Christianity, for example in the form of millenarianism or the Dominionists' idea of the God-state . At all times in church history there have been groups in and outside the church who pursued utopian goals, such as the Taborites or the Anabaptists in Münster . In Islam in particular, there are comparable currents that want to establish a real state of God ( theocracy ) with strong utopian traits (see also: Iran , Islamic Revolution ).

Scientific and technical utopias

In scientific and technical utopias, thanks to technical progress, not only the human living conditions but also the people themselves can be manipulated. Illness, hunger and death should be defeated by technical means and the nature of the human being should be changed in a targeted manner (see transhumanism ).

In the scientific world one hopes for a “ theory for everything ” from the utopias as well as the possibility to understand, describe and reproduce metaphysical entities such as life or consciousness (cf. artificial intelligence ).

In his book "Hightechmärchen", Hilmar Schmundt gives the following examples of scientific and technical utopias:

- the utopia of manned space travel and the colonization of the universe ,

- the utopia of a worldwide community through the Internet ,

- the utopia of the redemption of mankind from disease, hunger and death through genetic engineering

Philosophical concept of utopia

Utopia as a pre-appearance

Utopia is “thinking ahead” ( Ernst Bloch ) as “the criticism of what is and the representation of what should be” (Max Horkheimer). The extent to which utopia can be designed as a “concrete utopia” (Ernst Bloch) has been a matter of dispute since Georg Lukács' “ban on images” in 1916. "Any attempt to shape the utopian as being only ends in a form destroying"

Quasi as an antithesis to this statement, Bloch shows in principle hope the “fragmentary”, the “utopian remnant of images in realization” across the history of philosophy, literature and art, and turns against the “rounded satisfaction” and “immanence without disruptive leaps” “Of the seemingly completed, constantly refers to the“ not yet ”that is contained in the“ not ”. Already in the “foundation” of his main work he contrasts the daydream as a constituent element of the utopian as a “consciously creating, transforming fantasy” with the “subconscious chaos” of the night dream and the utopian in opposition to the mythical, in which it is nevertheless always again shows the unfinished business that still needs to be realized with the dialectical goal of "naturalizing man, humanizing nature"

The utopia is rooted in myth. Unlike this, however, it is not a preconscious collective narrative, but conscious individual creation. This already shows its etymology. The term of the Renaissance humanist and later Chancellor of the Exchequer Heinrich VIII. Thomas More, first made public in 1516, is a learned play on words: besides “ou-topos”, the “nowhere”, the namesake also refers to “eu-topos”, the “beautiful Place ”, and both are phonetically indistinguishable as“ utopia ”in English pronunciation. Utopia has been referring to the possible and the alternative to the existing since and with its name, also and especially as a social alternative. “Modern socialism begins with More's utopia” (Karl Kautsky).

In spite of its literary tradition, utopia is not a literary genre, "a linguistic determination of the type of text (...) is not possible". Rather, as a literary one, utopia is inextricably linked to the utopian way of thinking, it creates "counter images to the existing reality"

With his “Principle of Hope” Ernst Bloch wrote a kind of “History of Utopia”, in the history of philosophy based on “dynamei on”, the “possibility of being” of Aristotle with utopia as “pre-semblance”, which Immanuel Kant as “Aesthetic appearance” is differentiated from the “ transcendental appearance ” of the subjective fallacy. Bloch's utopian concept of “not yet” is essentially based on Marx's statement that the dream of a thing has long been present in the world that it only needs to be aware of in order to really own it. The demarcation of utopia from the purely utopian thus requires an understanding of the world as one in the process of becoming, as open, not yet finished and thought, with a tendency towards history and the latency of the horizon (“Man is always a learner, the world is an attempt, and man has her to shine ”).

Historical outline of utopian thinking

The design of a better world (“Well, I said, let's found a city in our minds from the beginning”) in the “Politeia” (2nd book, XI) and the detailed description of the legendary Atlantis with the central temple of Poseidon , the castle with silver walls and golden battlements and the canals that run concentrically through the city in “Kritias” (113b-121a) through Plato are, as two ideal images of the “polis”, the most important roots of utopia.

Plato's state, which neither seeks money nor does trade and whose upper class has a maximum of four times the "lower class", is contrary to the existing society of the time, but due to its strict hierarchy with exactly 5040 communities of rulers, guards and workers, it is a travel ban for under 40-year-olds and the limitation of art to the praise of the existing state, not aimed at the subjective well-being of its inhabitants, but rather at the functioning of the community as the best state.

His polygamy serves only eugenics , slavery has not been abolished. Atlantis, on the other hand, is only described architecturally, although "with the ideal urban architecture (...) an ideal community" should also be intended, as in Aristotle's "Politika" with the tradition of the architectural order of Hippodamus, which continued to have an effect up to the plans of the Italian architects of the Renaissance.

In contrast to the Platonic state, the sunny island of Jambulos stands in the 3rd century BC. BC as an "anarchist-egalitarian land of milk and honey, " which "does not know the institution of slavery" to which - conveyed by the Diodorian tradition - Lukian expressly refers to the True Stories and the trip to the moon in the 2nd century AD. Significantly, in times of Roman world domination it is the Hellenes from the colonies who portray their fictional journeys to a better world as a satire of the existing, while the Romans themselves prefer the "beatus illeg" of Horace and the bucolic idyll as ideal.

From the Christian Middle Ages, a number of architectural depictions of the Heavenly Jerusalem from the 9th to 12th centuries have been preserved, with a central temple and gold and silver walls analogous to Atlantis, but also the ideal monastic republic of the millennial kingdom of Joachim di Fiore, whose chiliasm continues to have an effect to the Anabaptists of Luther's time to the sunny state of Tommaso Campanella . Returning crusaders finally mixed in their stories the holy Jerusalem with the fairy-tale cities of the Orient, as in the chronicle of Duke Ernst from the 13th century, which reports on the distant Grippia, with a city wall made of marble and gold-covered palaces - similar to the brass city from a thousand and one nights .

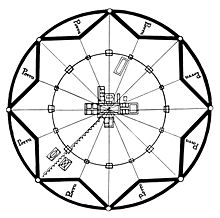

The Italian Renaissance with its Greek sources then prepared the ground for the first utopia that bears this name, and it was its architects, above all Leon Battista Alberti (De re sedificatoria, 1451) and Antonio di Pietro Averlino (Averulino or Filarete) the plan for the ideal city of Sforzinda (1464) named after Francesco I. Sforza , which is strongly based on Atlantis. Both wanted to create the ideal society with the ideal city.

At the beginning of the modern era, utopia was given a name and a program. In 1516, a year before Luther slammed his theses on the church door in Wittenberg and Magellan set out for the first circumnavigation of the world, Thomas More's utopia appeared as a fictional travelogue about an island whose capital Amaurotum (city of fog) clearly points to London. On the one hand, Utopia is a “fantasy land, but at the same time closed reform program”. The achievements of the Utopians, abolition of private property, six hours of daily work, 30 families merging into a family association, election of civil servants for one year, tolerance in questions of faith contrasted here with the reality of English society. The French Renaissance humanist Rabelais made explicit reference to Utopia in his Gargantua in 1534 with the description of the Thélemè Abbey, where young men and women live together without the usual vows according to the motto “Fais ce que vouldras” (do what you want). However, this “anarchist luxury commune” makes no claim to serve as a general model.

The series of "state novels" of the Renaissance, labeled as such in the 19th century (for example by Robert von Mohl 1855), was continued by the Calabrian monk and humanist Campanella in 1602 in Neapolitan imprisonment after he was accused of conspiracy against Spanish rule in southern Italy. Campanella's La Città del Sole, identifiable in Tapobrane, i.e. Sri Lanka , is ruled by the metaphysician Sol and determined by the course of the stars, from choosing a husband to eating meals. The seven number of planets also determines the architectural structure of the sun city, which is much closer to Plato's state than More's utopia, even though Campanella often refers to More. The third of the “classical” utopias, Francis Bacon's “Nova Atlantis” appears in 1627, on the threshold of the Baroque. Francis Bacon, Lord Chancellor under James I and known to this day for his dictum “Knowledge is Power” sees himself in the succession of More and intends to write a book “about the best state constitution”. The island of Bensalem in the Indian Ocean is depicted, and the center of the community is the House of Salomon. It is science that rules here, but in turn is brought closer to the people by a small elite.

Johann Valentin Andreaes Christianopolis of 1619, based on the ideals of the Rosicrucians, with a city without hunger, poverty and disease, with general property and material equality , also refers expressly to More. However, for the Swabian pastor Andreae, life is above all worship.

In 1611 the concept of utopia was first noted in a lexicon; there he explicitly referred not only to Thomas More's ideal state, but to all similar designs such as the Campanellas La città del sole (1602). In the 18th century the concept of utopia became a generic literary term, but criticism of the unrealistic designs had been reported since the 16th century.

After the humanism of the Renaissance, during and after the turmoil of the Thirty Years' War and the subsequent English Civil War in the Baroque era, there was a general drought for utopian thinking, and when it does appear it is usually godly. In England in particular, the King and the opposition, Oliver Cromwell and the Republicans repeatedly accused each other of pursuing utopian goals. In 1648 Samuel Gott's Nova Solyma (with the significant subtitle "Jerusalem regained"), which is often also attributed to John Milton , depicts a "state of God" established in Israel. A first glimmer of the Early Enlightenment is shown in 1656 by James Harrington's Oceana . In the direct examination of Thomas Hobbes ' absolute concept of sovereignty in the Leviathan (1651), a draft treaty with representation, rotation of offices and a bicameral system is drawn up, which later found essential parts of the constitution of the United States through John Adams. But only on the basis of John Locke's philosophy and after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 did the utopian regain a foothold in the Enlightenment of the 18th century, whereby it mostly played into the satirical, as with the Yahoos in Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels of 1726 or in El Dorado in Voltaire's Candide 1759, where the children play with precious stones, the food is free and theologians are unknown. How strongly the utopian remains tied to its time is shown by Mercier's “L'an 2440” in 1770, in which the separation of powers and federalism prevail - albeit under Louis XXXIV.

During the German Early Enlightenment, utopia was judged rather skeptically from different perspectives. While theologians doubt that a world without sinners is possible, philosophers like Christian Wolff assume that the world created by God is reasonable and the best of all worlds, so that utopias are superfluous. In France, however, where writers and philosophers question the historically evolved order with political constructions of contract theory , they expose themselves to its critique of utopianism.

In the 19th century, utopias became a concrete project as a social utopia, and the authors worked on turning their plans into reality. Fourier's society, ordered according to the passions of its inhabitants, in which the pyromaniac becomes the ideal firefighter, with its “Phalensteres” ( theory of quattre mouvements, 1808) remained a dream and Fourier waited in vain for a sponsor all his life through whom he gave his Could have turned plans into reality. Even Robert Owens New Harmony without marriage, religion and private property, based on 1820 in The Social System was not able to survive in reality, the project ruined Owen within three years. In 1842, Étienne Cabet's trip to Icaria appears as a communist ideal. Like Owen, Cabet wanted to realize his project in America, but it also failed after a short time. Karl Marx criticizes the theories of Owens and the French utopian socialists as "fantastic hindsight of the individual pedant"; they are not anchored in social practice. For Ernst Bloch , Karl Marx's theories are “lead in the wing shoes” of utopia precisely because of their scientific nature. After Friedrich Engels “Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science” of 1880, no more utopian system design was created that sought to transcend reality, especially since the last blank spots on the world map have now disappeared and utopia is moving from space into time .

Gustav Landauer put utopia in relation to topie. He saw Topie as a “general and comprehensive mix of coexistence in a state of relative stability”, while Utopia describes “a mix of individual strivings and volitional tendencies” that “are always heterogeneous and individually present, but in a moment of crisis through the form of the to unite and organize enthusiastic intoxication into a whole and into a form of coexistence ”(in: Die Revolution, 1907).

Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward 2000–1887 shows a technical future utopia of “industrial republics”, while practically simultaneously in 1890 William Morris imagined in News from Nowhere a London in which the protagonist, after 40 years of sleep, experiences that industry has been abolished again, the city districts have become villages again, replacing iron bridges with wooden bridges.

The philosophical reflection on the concept of utopia took place in the beginning after the First World War for the first time through Ernst Bloch's Geist der Utopie in 1918 and then reinforced from around 1930 by Walter Benjamin , Theodor W. Adorno , Max Horkheimer and Herbert Marcuse . Centrally, however, the philosophical concept of utopia remains associated with Bloch primarily on the basis of the principle of hope (1954–1959). A systematic continuation of Bloch's philosophy is still pending. Thus, according to Bloch, the further development of the concept of the utopian is also essentially driven theoretically by the writers, in the forefront by Lars Gustafsson (“It is characteristic of a utopia that it implies a system-transcendent criticism”) and Italo Calvino (“É semper il luogo qui mette in crisi l'utopia ”). Calvino sees the utopia of today as "polverizzata" and in the last lines of the " Invisible Cities " , Marco Polo has to sum up that one must "look for and know who and what in the mean of hell is not hell and give it continuity and space"

Even the literary utopia of the 20th century, beyond the pessimism of the dystopia of George Orwell's 1984 and Aldous Huxley's Brave New World - only leads a niche existence. Robert Musil's protagonist Ulrich im Mann ohne Qualitaet from 1930 reflects on the utopian, but wants to shape his life as an individual utopia without the need to change the community. Utopian aspects appear most obvious in the second half of the 20th century - especially with the “hidden cities” - in the above-mentioned “Citta invisibili” Italo Calvinos from 1972. As a “green” utopia, Ökotopia by Ernest Callenbach appears in 1975 , whereby a number of the ecological aspects described there have been realized in the meantime, social and political conditions with the president, ministers and state secretaries as well as the continued monetary economy including (at least limited) differences in earnings and private schools (without public competition) remain in the system intrinsic or even the prevailing US economic liberalism still amplify. Taxes still exist - but only as property tax.

As in evidence of Calvino's thesis, utopian thinking and Bloch's aftermath remain sporadic in the literal sense of the word. Thus, Jean-François Lyotard in power of the tracks for the first time recognized in 1930 explained in the "tracks" methodology for discovery utopian moments (Berlin 1977) Bloch to refer not compromising on the systematics of Bloch's thinking. Bloch's legacy is more evident in Alexander Kluge's when he answers the question “What to do?” In an interview with Spiegel on his 80th birthday: “Think in the subjunctive, look for options and possibilities in the light of history and the future. "

See also

- automation

- Utopian

- Heterotopia (humanities)

- Counterfactual History (Uchronie)

- Atopy (philosophy)

literature

Alphabetical

- Alexander Amberger, Thomas Möbius (Ed.): On Utopia's footsteps. Utopia and Utopia Research. Festschrift for Richard Saage . Heidelberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-658-14045-8 .

- Ulrich Arnswald, Hans-Peter Schütt (ed.): Thomas More's Utopia and the genre of utopia in political philosophy. Karlsruhe 2010, ISBN 978-3-86644-403-4 . (EUKLID: European Culture and History of Ideas. Studies Volume 4).

- Jörg Albertz (Ed.): Utopias between claim and reality. Bernau 2006, ISBN 3-923834-24-1 . (Series of publications by the Free Academy, Volume 26).

- Harold C. Baldry: Ancient utopias , Southampton 1956.

- Marie-Louise Berneri : Journey through Utopia. A reader of utopias. Kramer, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-87956-104-4 .

- Lucio Bertelli: L'Utopia greca , in: L. Firpo (ed.), Storia delle idee politiche, economiche e sociali , Vol. I: L'antichità classica, Turin 1982, pp. 463-581.

- Reinhold Bichler: On the historical assessment of the Greek state utopia , in: Grazer Contributions 11, 1984, pp. 179-206.

- Wolfgang Biesterfeld: The literary utopia. Metzler, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-476-12127-5 .

- Ernst Bloch : The principle of hope . Frankfurt a. M. 1959.

- Ernst Bloch: Revolution of Utopia. Texts by and about Ernst Bloch, edited by Helmut Reinike. Frankfurt a. M. 1979, ISBN 3-593-32386-9 .

- Katharina Block: Social utopia - presentation and analysis of the chances of realizing a utopia. wvb, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-86573-602-4 .

- Horst Braunert: Utopia - Answers of Greek thought to the challenge posed by social conditions , Kiel 1969.

- Marvin Chlada : The will to utopia. Aschaffenburg, Alibri-Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-932710-73-8 .

- Arrigo Colombo: L'utopia - Rifondazione de un'idea e di una storia , Bari 1977.

- Doyne Dawson: Cities of the Gods - Communist utopias in Greek thought , New York / Oxford 1992.

- Sascha Dickel, Jan-Felix Schrape : Decentralization, Democratization, Emancipation On the architecture of digital technology utopianism . In: Leviathan. 3/2015, pp. 442-463, doi : 10.5771 / 0340-0425-2015-3-442 .

- Ulrich Dierse: Art. "Utopia" , in: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , ed. v. J. Ritter, K. Founder u. G. Gabriel, Vol. 11, Darmstadt 2001, Col. 510-526.

- Thomas Eicher u. a. (Ed.): The golden age. Utopias around 1900 . In: StudienPROJEKTE-PROJEKTstudien. Vol. 2, Bochum / Freiburg i.Br. 1997, ISBN 3-928861-93-X .

- John Ferguson: Utopias of the Classical World , London 1975.

- Hans Freyer: The political island - a history of utopias from Plato to the present , Leipzig 1936.

- Heiner Geißler : Ou Topos - search for the place that should be. Rowohlt Tb 62638, Reinbek b. Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-499-62638-8 .

- Hiltrud Gnüg: utopia and utopian novel. Reclam, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-15-017613-1 .

- Steffen Greschonig: Utopia - Literary Matrix of Lies? A discourse analysis of fictional and non-fictional possible and feasible thinking. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 2005, ISBN 3-631-53815-4 .

- Rigobert Günther u. Reimar Müller: The Golden Age - Utopias of Hellenistic-Roman Antiquity , Stuttgart 1988.

- Klaus J. Heinisch (Ed.): The utopian state. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, 1960, ISBN 3-499-45068-2 .

- Lucian Hölscher: Article "Utopia" , in: Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe - Historisches Lexikon zur Politico-Social Sprachsprache in Deutschland , ed. v. O. Brunner, W. Conze, R. Koselleck, Vol. 6, Stuttgart 1990, pp. 733-790.

- Karl R. Kegler, Karsten Ley and Anke Naujokat [Hrsg.]: Utopische Orte. Utopias in the history of architecture and urban construction. RWTH Forum Technik u. Society, Aachen 2004, ISBN 3-00-013158-2 .

- Reinhart Koselleck: Temporalization of Utopia. In: Wilhelm Vosskamp (ed.): Utopia research. Third volume, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1985, pp. 1-14.

- Oliver Krüger : Gaia, God, and the Internet - Revisited. The History of Evolution and the Utopia of Community in Media Society. In: Online - Heidelberg Journal for Religions on the Internet 8 (2015).

- Krishan Kumar: Utopianism , Bristol 1991.

- Till R. Kuhnle: Utopia, Kitsch and Catastrophe. Perspectives of an analytical literary science. In: Hans Vilmar Geppert, Hubert Zapf (Ed.): Theories of Literature. Basics and perspectives I. Francke, Tübingen 2003, pp. 105–140. (treats utopia as a concept of existence)

- Till R. Kuhnle: The trauma of progress. Four studies on the pathogenesis of literary discourses. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-86057-162-1 . (deals in particular with the relationship between utopia and eschatology).

- Karl Mannheim : ideology and utopia. Neuwied 1952.

- Frank E. Manuel and Fritzie P. Manuel: Utopian thought in the Western world , Cambridge / Mass. 1979.

- Rudolf Maresch , Florian Rötzer (Ed.): Renaissance of Utopia. Figures of the future of the 21st century. Edition Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-518-12360-2 .

- Alexander Neupert-Doppler : Utopia. From a novel to a figure of thought. Butterfly Verlag, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 3-89657-683-6 .

- Alexander Neupert-Doppler (ed.): Concrete Utopias. Our alternatives to nationalism. Butterfly Verlag, Stuttgart 2918, ISBN 3-89657-199-0 .

- Arnhelm Neusüss : Utopia. Concept and phenomenon of the utopian. 3. Edition. Frankfurt am Main / New York 1986, ISBN 3-593-33592-1 . (Arnhelm Neusüß (ed.): Sociological texts. Vol. 44, Darmstadt / Neuwied 1968; 2nd edition. 1972).

- Thomas Nipperdey: The Function of Utopia in Modern Political Thought. Archives for Cultural History (44), 1962.

- Yann Rocher: Théâtres en utopie. Actes Sud, Paris 2014.

- Richard Saage : The end of political utopia? Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / M. 1990.

- Richard Saage: Political Utopias of the Modern Age. WBG, Darmstadt 1991.

- Richard Saage: Utopian Profiles. Volume 1: Renaissance and Reformation . LIT Verlag, Münster 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5428-0 .

- Richard Saage: Utopian Profiles. Volume 4: Contradictions and Syntheses of the 20th Century . LIT Verlag, Münster 2004, ISBN 3-8258-5431-0 .

- Thomas Schölderle: History of Utopia. An introduction. 2., revised. and actual Ed., Böhlau (UTB), Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-8252-4818-5 .

- Thomas Schölderle: Utopia and Utopia. Thomas More, the history of utopia and the controversy surrounding its concept. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2011, ISBN 978-3-8329-5840-4 .

- Thomas Schölderle (Ed.): Ideal State or Thought Experiment? On the understanding of the state in classical utopias. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2014, ISBN 978-3-8487-0312-8 .

- Ferdinand Seibt : "Utopica - Models of Total Social Planning". Düsseldorf 1972.

- Ferdinand Seibt: Utopica. Future visions from the past. Orbis, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-572-01238-4 .

- Peter Seyferth: Utopia, Anarchism and Science Fiction. Ursula K. Le Guin's works from 1962 to 2002 . Lit, Münster 2008, ISBN 978-3-8258-1217-1 .

- Helmut Swoboda: Utopia - History of Longing for a Better World , Vienna 1972.

- Arno Waschkuhn: Political Utopias. A political theory overview from antiquity to today. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-27448-1 .

- Manfred Windfuhr: visions of the future. Of Christian, green and socialist paradises and apocalypses. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2018, ISBN 978-3-8498-1133-4 .

- Johanna Wischner, Thomas Möbius, Florian Schmid (eds.): The gap in utopia - criticism, empowerment, consolation, main focus in: Berliner Debatte Initial . Issue 2/2016. ISBN 978-3-945878-09-5 .

- Gisela Zoebisch: Utopia and Historicism. On the problem of the anticipatory regularity of historical designs. Bayreuth 1993.

Movie

- Living the utopia - Vivir la utopia. The anarchism in Spain . A film about utopia lived during the Spanish Civil War by Juan Gamero, 1997.

- Away from all suns . Documentary about the social utopia of the early Soviet Union based on the buildings of constructivism, 2013.

- Zoomania . Originally Zootopia, reference to the English word for otopia, utopia. Representation of today's society in the form of an animated film through a caricature with anthropomorphic animals living in the fictional city of Zoomania / Zootopia, 2016.

Web links

- Arnswald, Schütt (Ed.): Thomas More's Utopia and the Genre of Utopia in Political Philosophy (full text)

- Rolf Schwendter: Utopia

- Utopia and Utopianism academic journal specializing in utopian studies

- Friday debate: utopia in concrete terms - what to do when nothing works

- Spektrum .de: The Utopia - Story of a Misunderstanding August 31, 2019

- Utopia Network Collection of texts on political utopias

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dream of a Better Life - Utopias in Art , June 2020, WELTKUNST magazine, page 16 ff.

- ↑ See Patricia Broser. A day will come ... . Praesens, Vienna 2009, p. 42.

- ^ Richard Saage: Utopian Profiles. Volume 4: Contradictions and Syntheses of the 20th Century . Münster 2004, p. 6.

- ^ Richard Saage: Utopian Profiles. Volume 1: Renaissance and Reformation . Münster 2001, p. 78.

- ^ Richard Saage: Utopian Profiles. Volume 1: Renaissance and Reformation . Münster 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Peter Ackroyd: The Life of Thomas More. Anchor Books, New York 1999.

- ^ Walter Otto Ötsch: The neoliberal utopia as the end of all utopias. In: Sebastian Pittl, Gunter Prüller-Jagenteufel (ed.): On the way to a new "civilization of shared frugality". 2016, pp. 105–120, quote: p. 115.

- ↑ Zygmunt Bauman: Retrotopia . Cambridge 2017.

- ↑ Georg Lukacs: Theory of the novel. Darmstadt 1981, p. 137.

- ↑ Ernst Bloch: The principle of hope. Frankfurt 1978, p. 252.

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ op.cit, p. 113.

- ↑ op.cit. P. 241.

- ^ Wolfgang Biesterfeld: The literary utopia. Stuttgart 1974, introduction.

- ^ Biesterfeld: The literary utopia. 1974, p. 14.

- ^ Wilhelm Vosskamp: Utopia research. Stuttgart 1982, introduction, p. 4.

- ^ Marx / Engels: Works. Berlin 1968, Volume 1, p. 346.

- ↑ Ernst Bloch: Preliminary remark to the Tübingen introduction to philosophy. Frankfurt 1977.

- ↑ Michael Winter: Compendium Utopicarum. Stuttgart 1978, p. 2.

- ↑ Helmut Swoboda : The dream of the best state. Munich 1972, p. 36.

- ↑ Winter: Compendium Utopicarum. 1978, p. 8.

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Reske: Jerusalem caelestis. Göppingen 1973.

- ^ Ernst Bloch: Thomas Münzer. Frankfurt 1976, p. 58 f.

- ↑ Herzog Ernst: A medieval adventure book. ed. v. Bernhard Sowinski, Stuttgart 1970.

- ↑ Klaus J. Heinrich: The utopian state. Reinbek 1969, afterword, p. 232.

- ↑ Swoboda: The dream of the best state. 1972, p. 58.

- ↑ Swoboda: The dream of the best state. 1972, p. 89.

- ↑ Swoboda: The dream of the best state. 1972, p. 7.

- ↑ Klaus J. Heinrich, op.cit., P. 229.

- ↑ Ernst Bloch: The principle of hope. Frankfurt 1978, p. 744.

- ↑ Swoboda: The dream of the best state. 1972, p. 131 f.

- ^ Utopie , in: HWPh 11, 2001, Sp. 510.

- ↑ Winter: Compendium Utopicarum. 1978, p. 77.

- ↑ Louis-Sébastien Mercier: The year 2440. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1982, ISBN 3-518-37176-2 .

- ^ Utopie , in: HWPh 11, 2001, Col. 512-513.

- ^ Karl Marx: The class struggles in France 1848-1850. In: MEW Volume 7, p. 89.

- ^ Lars Gustafsson: Utopias. Munich 1970, p. 86.

- ^ Italo Calvino: Una pietra sopra. Torino 1980, p. 253.

- ↑ ibid, p. 254.

- ^ Italo Calvino: The Invisible Cities. Munich 1977, p. 176.

- ↑ Robert Musil: The man without qualities. Reinbek 1978.

- ^ Ernest Callenbach : Ökotopia. Berlin 1978.

- ↑ SPIEGEL 2/2012, Hamburg.