Karl Mannheim

Karl Mannheim (born March 27, 1893 in Budapest , † January 9, 1947 in London ), originally Károly Manheim, was a sociologist and philosopher of Austro-Hungarian origin, Jewish religion, German and British citizenship .

Life

Mannheim studied philosophy and sociology in Budapest , Freiburg , Berlin (where he heard Georg Simmel in 1914 ), Paris and Heidelberg . Together with Arnold Hauser and Erwin Szabó , Mannheim is the founder of the Budapest Free School for the Humanities, at which Georg Lukács also gave lectures. In 1918 he was promoted to Dr. phil. PhD. A year later he turned his back on his home country Hungary and subsequently emigrated to Germany . From 1922 to 1925 he completed his habilitation with the cultural sociologist Alfred Weber , Max Weber's brother , became a private lecturer in Heidelberg in 1926 and, on the initiative of Adolf Grimme, became a full professor of sociology at the University of Frankfurt in 1930 ; there Norbert Elias was at his side as an assistant.

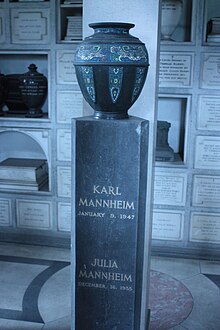

Mannheim was dismissed in 1933 due to its Jewish descent. He emigrated to England, where his secretary Greta Lorke supported him. There, through the mediation of Harold Laski and Morris Ginsberg, he became a lecturer in sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science and later Professor of Education at the University of London . Mannheim was married to the psychoanalyst Julia Lang (1893–1955). He was in the Golders Green Crematorium in London cremated , where his ashes is located.

Scientific work

Influenced in particular by Georg Lukács, Oszkár Jászi , Wilhelm Dilthey , Georg Simmel , Max Scheler , Max Weber and Alfred Weber , Mannheim moved from a philosophical analysis of epistemology to the development of the sociology of knowledge . He emphasized that human thinking and cognition do not take place in a purely theoretical framework, but are shaped by social and historical life contexts (philosophy of life). From this he developed a model of "epistemic relationism", which states that worldviews change depending on the position in society, and thus overcame the substantialist thinking that he strongly criticized. "Ideologies" mean nothing other than the absolutization of particular worldviews that are used and abused by parties again and again ("suspected ideology").

With the conception of the "total ideology concept " Mannheim took a radical knowledge-sociological position, which argued relativistically and was described by opponents as nihilistic . In contrast, he himself describes his approach as “dynamic relationism”. In contrast to Karl Marx , Mannheim postulated an ideological concept that determines all thinking, including one's own, as ideological. H. "ideological", considered, because it is necessarily perspective. He has detailed this v. a. shown for conservative , liberal and socialist thinking.

Mannheim dealt with political crises in mass democracy . In contrast to the one-sided sentiment and laissez-faire- liberalist democracy , which includes the risk of turning into a totalitarian dictatorship , Mannheim recommended as a third way the “planned democracy” with “planning for freedom”, whereby planning “as rational domination of irrational forces ”. The society of “planned freedom” presupposes the transformation of the human being. Karl Mannheim, who was close to the religious socialists around Paul Tillich and the Christian group Moot around TS Eliot , emphasizes that cooperation between sociologists and theologians is important.

His adaptation of Alfred Weber's concept of " free-floating intelligence " is part of Mannheim's influential sociology of intelligence . He is also considered a pioneer of youth sociology . In his text "The Problem of the Generations" he re- coined the term generation in order to summarize cohorts ( cohorts ) who shared a decisive youth experience (e.g. the First World War ) and were thus faced with identical tasks ("life" or “generation connections”), but solved these differently depending on the class situation (“conjunctive experience space”).

Mannheim's differentiation between communicative and conjunctive knowledge was of particular importance for a “praxeological sociology of knowledge” (Bohnsack 2007, 2008) and the documentary method developed in this context . The latter sees Mannheim as atheoretisches and implicit experiential knowledge, which (unlike the explizierbare and reflexive available communicative knowledge within the meaning of Common Sense ) daily everyday practice largely unnoticed guides (in the sense of the later Bourdieu developed habit ). The documentary method is dedicated - as a further development of Mannheim's sociology of knowledge - to researching this form of tacit knowledge.

criticism

The importance of Mannheim's Ideologie und Utopie (1929) as well as the extended English translation can be seen from the broad debate that both provoked. Reviews by Hannah Arendt , Max Horkheimer , Herbert Marcuse , Paul Tillich , Günther Stern (Anders) , Karl A. Wittfogel and others have appeared in Germany. In the US , the reviewers were u. a. Hans Speier , Robert King Merton , Kenneth Burke and Charles Wright Mills . His English writings were welcomed by John Dewey and others; but violently attacked by Karl Popper .

Mannheim's proposal for a “planned democracy” and “planning for freedom” was sharply attacked by Friedrich August von Hayek in his book Der Weg zur Knecherschaft . Hayek argued that even planned economy measures initially adopted by democracies would inevitably come into conflict with individual rights and thus - if not necessarily intended - would pave the way to totalitarian systems . These would then operate the "reshaping of people" by means of violence. Accordingly, a tendency to restrict the rule of law in favor of supposedly higher ideals can already be seen in Mannheim's work .

Nick Abercrombie developed a review of Mannheim's work, which he published together with St. Hill and B. Turner in 1980 under the title The Dominant Ideology Thesis .

Works

- The structural analysis of epistemology . Berlin 1922.

- Ideology and utopia . Bonn 1929 (later editions published in Frankfurt am Main).

- The contemporary tasks of sociology . Tübingen 1932.

- People and society in the age of reconstruction . Leiden 1935. Partly changed and greatly expanded as Man and Society in an Age of Reconstruction . London 1940 (German translation Man and Society in the Age of Reconstruction . Darmstadt 1958)

- Diagnosis of our Time . London 1943 (German 1951).

- Freedom, Power and Democratic Planning . London 1951 (German 1970).

- Sociology of knowledge. Selection from the factory . Edited by Kurt H. Wolff. Luchterhand, Neuwied / Berlin 1964.

- Structures of thought . Edited by David Kettler, Volker Meja and Nico Stehr. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1980.

- Conservatism . Edited by David Kettler, Volker Meja and Nico Stehr. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1984.

Secondary literature

- Theodor W. Adorno : The consciousness of the sociology of knowledge , in: Prisms. Cultural criticism and society , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1955

- Gregory Baum : Truth Beyond Relativism: Karl Mannheim's Sociology of Knowledge , The Marquette Lecture, Marquette University Press, 1977

- Blomert, Reinhard : Intellectuals on the move. Karl Mannheim, Alfred Weber, Norbert Elias and the Heidelberg social sciences of the interwar period , Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 1999

- Ralf Bohnsack: Documentary method and praxeological sociology of knowledge , in: R. Schützeichel (ed.): Handbuch Wissenssoziologie und Wissensforschung , UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, Konstanz 2007, pp. 180–190.

- Ralf Bohnsack: Reconstructive social research. Introduction to qualitative methods , Barbara Budrich, Opladen / Farmington Hills 2008.

- Bálint Balla : Karl Mannheim , Reinhold Krämer, Hamburg 2007

- Michael Corsten : Karl Mannheims Kultursoziologie , Campus, Frankfurt am Main. ISBN 3-593-39156-2 .

- Dirk Hoeges : Controversy on the brink: Ernst Robert Curtius and Karl Mannheim. Intellectual and “free-floating intelligence” in the Weimar Republic , Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-596-10967-1 .

- Wilhelm Hofmann: Karl Mannheim for the introduction , Junius, Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-88506-938-5 .

- Thomas Jung: The being-boundness of thinking. Karl Mannheim and the foundation of a sociology of thought , Bielefeld 2007.

- Dirk Kaesler : Mannheim, Karl. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-428-00197-4 , pp. 67-69 ( digitized version ).

- David Kettler: Marxism and Culture. Mannheim and Lukács in the Hungarian Revolutions 1918/1919 [From the American. English by Erich Weck; Tobias Rülcker]. Neuwied-Berlin: Luchterhand, 1967 [= sociological essays], 70 p.

- David Kettler / Volker Meja: Karl Mannheim and the Crisis of Liberalism , Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick / London, 1995.

- David Kettler / Volker Meja / Nico Stehr : Political Knowledge. Studies on Karl Mannheim. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-518-28249-2 .

- Reinhard Laube : Karl Mannheim and the crisis of historicism. Historicism as sociological perspectivism , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-35194-1 .

- Volker Meja / Nico Stehr: The dispute about the sociology of knowledge , 2 vols., Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-518-07961-1 .

- Arnhelm Neusüß : Utopian awareness and free-floating intelligence. On the sociology of knowledge by Karl Mannheim , Meisenheim am Glan 1968.

Web links

- Literature by and about Karl Mannheim in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Karl Mannheim in the German Digital Library

- Biography Karl Mannheim at the Internet Lexicon 50 Classics of Sociology .

- Karl Mannheim, The Problem of the Generations, 1928 , in: 1000dokumente.de

- Mannheim, Karl. Hessian biography. (As of February 14, 2020). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- Mannheim, Karl in the Frankfurt personal dictionary

Individual evidence

- ^ Raddatz, Fritz J .: Lukács, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1972, p. 37.

- ^ History of the Institute for Social Research 3 The pre-war period in Frankfurt ( Memento from May 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: ifs.uni-frankfurt.de

- ↑ Greta Kuckhoff: From the Rosary to the Red Chapel. A life report , New Life, Berlin 1976

- ↑ Éva Karádi, Erzsébet Vezér [ed.]: Georg Lukács, Karl Mannheim and the Sunday Circle , Frankfurt am Main: Sendler 1985, p. 314

- ↑ Wolfgang Schluchter : The emergence of modern rationalism. An analysis of Max Weber's history of the development of the Occident . 1st edition Frankfurt am Main 1988. ISBN 3-518-28947-0 . P. 87, note 39: “Some of Mannheim's ideas can be used to explain Weber's theory of value. This is not accidental if you consider that Mannheim also began with the Rickert - Lask philosophy and a criticism of it. "

- ↑ See Reinhard Blomert: Intellectuals on the move. Karl Mannheim, Alfred Weber, Norbert Elias and the Heidelberg social sciences of the interwar period . Hanser, Munich 1999, p. 192, ff

- ^ Karl Mannheim: The problem of the generations . Cologne Quarterly Issues for Sociology, No. 7 , 1928, pp. 157-185, 309-330 .

- ↑ See Mannheim 1980, p. 155 ff.

- ^ Karl Mannheim: Ideology and Utopia. Vittorio Klostermann, 1995, ISBN 9783465028222 restricted preview in the Google book search

- ↑ Hannah Arendt: Philosophy and Sociology . Review. In: Die Gesellschaft, 1930, p. 163 ff.

- ↑ Max Horkheimer: A new concept of ideology? In: Max Horkheimer, Gesammelte Schriften Vol. 2: Philosophische Frühschriften 1922–1932, Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1987

- ↑ Stern (Anders), Günther: About the so-called 'being connectedness' of consciousness. On the occasion of Karl Mannheim 'Ideologie und Utopie' In: Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, 64. Vol., 1930, pp. 492–509

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Mannheim, Karl |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Hungarian-German philosopher and sociologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 27, 1893 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Budapest |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 9, 1947 |

| Place of death | London |