The right to be lazy

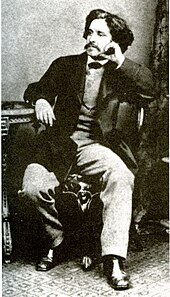

The right to be lazy (in the original: Le droit à la paresse ) is a literary work by Paul Lafargue from 1880 to refute the “ right to work ” from 1848. It is Lafargue's best-known font. It first appeared in L'Égalité magazine and three years later as a paperback . Eduard Bernstein translated the text into German for the magazine Social Democrat .

content

In his work, Lafargue criticizes the ideological ( moral ), bourgeois (“ bourgeoisie ”) and capitalist foundations of the concept of work of his time. He also criticizes the labor movement , which is dominated by the "strange addiction", the " work addiction" . He speaks of the "love of work, the frenzied addiction to work that goes to exhaustion of individuals and their descendants". The aim of his criticism is not the demand for a basic right to be lazy , but the abolition of capitalist modes of production. The “capitalist morality” is “a pathetic copy of Christian morality, places a curse on the flesh of the worker; their ideal is to keep the needs of the producer to a minimum, to stifle his joy and passions, and to condemn him to the role of a machine from which work is continuously and mercilessly teased. "

He criticizes the bourgeois philosophers as dependent on their employers, in whose sense they provided the necessary morality of work. Using the example of Herodotus , he contrasts them with Greek philosophy and its contempt for work.

Specifically, Lafargue describes the function of the workhouses, the emergence of a "religion of work", the conditions of work for men, women and children as well as the daily working time of 12 hours. In contrast to the labor movement, he sees no progress in the law of 1848: “And the children of the heroes of the French Revolution have allowed themselves to be degraded by the religion of work to such an extent that in 1848 they passed the law that works in factories be 12 hours daily limited when accepted as a revolutionary achievement; they proclaimed the right to work as a revolutionary principle. Shame on the French proletariat! "

With exoticising images Lafargue describes his ideas about the luck of the pre-industrial way of life: the machine-man of " civilization " he romanticized disputes the "noble savage". At the same time he criticizes colonialism as a consequence of overproduction and as a danger for the people in the continents to be conquered.

His criticism was at the same time a criticism of the bourgeois concept of the nation , which he also sarcastically formulated: “Work, work, proletarians, increase national wealth and with it your personal misery. Work, work, in order, having become poorer and poorer, still more cause to work and to be miserable. That is the inexorable law of capitalist production. "

The state and its organs such as the police - “emaciated proletarians wrapped in rags, guarded by gendarmes with bare blades” - and the military are also criticized. The actual task of the modern army is to prevent revolts: “Today nobody can be in the dark about the character of the modern army; they are only maintained in the long run to keep the "enemy within" down. "

In the appendix of the work, Lafargue also tries to substantiate his positions with quotations from ancient Greek and Roman authors such as Plato, Cicero and Xenophon. The statements ascribed to them show a very clear hostility towards the craft and trade, but can in no case be found in the original texts of the authors. Probably the quotations were unchecked from L.-M. Moreau-Christophes “ You droit a L'Oisiveté et de l'organization du travail servile dans les républiques grecques et romaine ”.

Classification according to Marxian theory and practice

Lafargue and his work "The Right to Laziness" contradicts Marx and Engels in large parts and places other emphases in the criticism of capitalism . In contrast to Marx and Engels, Lafargue rejects an idea of progress here. He also sees increased productive growth not as a solution, but as a problem of the impoverishment of working people. In contrast to Marx and Engels, Lafargue focuses on the critique of consumption , i.e. the sphere of consumption of capitalist production. Lafargue also reflects the conditions for working people after the revolution . Lafargue sees his fundamental criticism of nationalism as being based on the Communist Manifesto . Nevertheless he is criticized for this by Marx with the concept of proudhonized Stirnerianism , which is later criticized and persecuted primarily as cosmopolitanism . His internationalism also becomes the background for racist attacks on Lafargue as a " mulatto ".

reception

The script was published in many languages. His writings were long banned in the Soviet Union. “The right to be lazy” was not published in the following years either. In the Soviet encyclopedia Bol'schaja sovjetskaja enziklopedija from 1973 only Lafargue's struggle "against all kinds of opportunism " is emphasized. “The right to be lazy” is completely unmentioned.

In the FRG, “the right to be lazy” was only rediscovered in the wake of the New Left and the 1968 movement . In the period that followed, Lafargue's writings were published for the first time in the GDR - but not “The Right to Laziness”. When Iring Fetscher quotes from the Scriptures in the GDR, the criticism is: “Undermining work ethic”.

In 1972 the church historian Ernst Benz published on Lafargues “The Right to Laziness” and discussed a theology of laziness .

expenditure

- Le droit à la paresse . H. Oriol, Paris 1883.

- The right to be lazy: refuting the “right to work” . Verlag der Volksbuchhandlungen, Hottingen / Zurich 1887.

- The right to be lazy (with an introduction by Stephan Lessenich ). Laika-Verlag, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-942281-54-6 .

- The right to be lazy (with an introduction by Michael Wilk ). Nevertheless-Verlag, Grafenau 2010, ISBN 978-3-86569-907-7 .

Web links

- Right to be lazy at Wildcat

- Right to be lazy (PDF) at theopenunderground.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ See: Fritz Keller: Paul Lafargue .

- ↑ a b Fritz Keller: Paul Lafargue .

- ↑ Barbara Sichtermann: Karl Marx, the market and the media. Archived from the original on September 21, 2009 ; Retrieved June 29, 2017 .