The situation of the working class in England

The situation of the working class in England with the subtitle According to your own opinion and authentic sources is an important work and early writing by Friedrich Engels from 1845, in which he describes the social and economic conditions in England at the time of early industrialization . The book is considered a pioneering work of empirical social research and raises a damning charge against the English bourgeoisie , whose “unbridled greed for profit” makes Engels responsible for the impoverishment of the workers - up to and including “social murder”. The publication is a standard work of industrial and urban sociology and is described by UNESCO as a “masterpiece of ecological analysis”. The work achieved not least by linking empirical description and theoretical generalization enormous popularity and is considered a model for social, economic and cultural critical writings about for The Road to Wigan Pier by George Orwell . Conversely, Engels made use of motifs from contemporary pauperism literature , the most famous representative of which, Charles Dickens (1812–1870), with Oliver Twist (1839), presented the "social and societal grievances of the epoch without make-up". The Christian-humanitarian authors of the literature on pauperism wanted to eliminate the grievances, but not the causes. Despite its social importance, Engels work has been criticized for maintaining insufficient objectivity and failing to meet the standards of scientific field research recognized today .

To the work

Origin and content structure

The work was created after the then 24-year-old Engels spent 21 months in England, whereby experiences from previous visits in the previous two years and about the situation of the workers in his hometown of Barmen also played a role. Engels had visited numerous cities, including the “factory cities” of Nottingham , Birmingham , Glasgow , Leeds , Bradford and Huddersfield , larger cities with their own working -class neighborhoods such as London (St. Giles), Manchester and Liverpool, and the cities of Salford , Stalybridge , Ashton-under- Lyne , Stockport and Bolton . After his return in the summer of 1844, Engels processed the subject according to the subtitle of the work “according to his own view and authentic sources” on almost 400 pages, which he wrote down in Barmen from November 1844 to mid-March 1845 . He supplemented the evaluation of his personal impressions with contemporary sources such as newspaper articles, reports from official commissions such as inspections and scientific publications. The sources can be subdivided into statistical data from sociographic studies of a private and governmental nature as well as testimonies, analyzes and treatises by bourgeois authors who are not suspected of being Chartists or socialists, especially Thomas Carlyle . In a way, Carlyle was a “spark” for Engels and his portrayal of the English working-class situation, as Carlyle argued in his writings - such as Chartism (1839) and Past and Present (1843) - that the “leading classes” would become political self-deception "systematically refuse to" take the lead "and would therefore be unable to" remain the ruling class of society any longer ". In addition to the sources mentioned, Engels also used passages from his work Die Lage Englands from 1844 as well as parts of text from Peter Gaskell's study on the Manufacturing Population of England (1832) for the history of the development of the proletariat.

“I've lived among you long enough to know some of the circumstances of your life; I have devoted my most earnest attention to their knowledge; I have studied the various official and non-official documents as far as I had the opportunity to obtain them - I was not satisfied with that, I was concerned with more than just abstract knowledge of my subject, I wanted you in your homes see, observe you in your daily life, chat with you about your living conditions and pains, witness your struggles against the social and political power of your oppressors. "

Originally, the processing of the impressions of the England trip was planned "only as a single chapter of a more comprehensive work on the social history of England". In the foreword to the German first edition, however, he admits that the “importance” of the subject forced him to dedicate an independent study to it: “On the one hand, to the socialist theories, on the other hand, to give solid ground to the judgments about their justification give ”Engels intended with his work“ to reveal the circumstances and conditions truthfully - and that means in the objectified form of numbers, tables and statistics ”, which the bourgeoisie would have neglected until then. Accordingly, it seems conclusive that the "results of the investigation by the government commissions, the annual inspection reports and various socio-medical treatises" were quoted generously. In addition, Engels did not limit himself to depicting exploitation in the factories , but also describes the living conditions. It shows the entire spectrum of proletarian existence: health, housing, alcoholism, crime, child and women's labor as well as the exploitation by the truck and cottage system. These core themes can be found in numerous sections of the work.

Structurally, Engels first gives an introduction to the subject of the industrial revolution. It goes on to the emergence of the industrial proletariat and its living conditions in the big cities. He describes the fierce competition on the job market and connects this with the Irish immigration wave. Then he deals with the branches and activities of workers and their health and social consequences. As a logical conclusion to the living conditions presented, Engels analyzes the English labor movements. After explaining the mining and agriculture workers, he finally describes the position of the bourgeoisie towards the proletariat. According to Engels' conclusions, "the war of the poor against the rich, which is already being waged individually and indirectly, [...] in general, as a whole and directly, will be waged in England."

Release history

The German-language font was first published in Leipzig in 1845 by Otto Wigand , and a second edition followed in 1848. In 1887 an English translation was published in New York, authorized by Engels, to which, at the request of the translator Florence Kelley Wischnewetzky, a foreword and an appendix by Engels were added. This translation was reprinted in 1892 by "Swan Sunshine & Co" in London , whereby the foreword of the American edition was omitted, since it dealt primarily with the "modern American labor movement" and not in detail with the actual book content. Engels now used the appendix to the American edition, which was the original foreword, for the English foreword. Also in 1892, a second German-language edition, published by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Dietz , appeared in Stuttgart , which Engels reviewed and some of which were footnoted. This publication was also provided with a German-language foreword by Engels based on the English foreword. In 1903 and 1913 the font was reissued by Dietz. In addition to the two writings The German Peasant War and Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy , The Situation of the Working Class in England was the only work by Engels that was excluded from the book burnings of the National Socialists in 1933 . The Marxists Internet Archive makes the work available in a total of nine languages. The German National Library's online catalog contains around 45 publications of the font, beginning in 1848 and ending in 1993. Oxford University Press reissued the font in 2000.

Classification in Engels' work

At the age of 22, Engels, the son of a textile manufacturer, traveled to Manchester and, among other things, got to know the life of workers in a cotton mill. His political stance was shaped for life, and he began to come to terms with workers' organizations, including the League of the Just and the Chartists in Leeds . After meeting his long-time companion Karl Marx early on in 1842, a lasting friendship developed. A sustained exchange of letters and a meeting in August 1844 testified to the same social views - the basis for numerous joint publications.

With the socially critical portrayal in The Situation of the Working Class in England, Engels grounded his social criticism for the first time in a publication, the economic dimension of which he had previously described in his Critique of Economic Categories in the Franco-German Yearbooks (since 1844) and in Outlines a Critique of Political Economy (1844) had formulated. In his work, Engels processes approaches from the theory of the labor movement and the class struggle . It is not enough for him to express moral criticism. He formulates the irreconcilable opposition between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie as a necessary result of the capitalist division of labor and liberal competitive thinking , which inevitably leads to a revolutionary solution. The situation of the working class in England , particularly through its empirical detail, should pave the way for the economic and revolutionary theory of Marxism by Marx. Since in the eyes of Marx and Engels "the English workers were the firstborn sons of modern industry", the conditions there were seen as the first manifestations of a development that would be decisive for the working and living conditions in many other countries.

For Marx, Engels' The situation of the working class in England had "arrived at the same result" by other means "as he did, which ultimately led them to express their" view against the ideological " in the unpublished work Die deutsche Ideologie (1845) of German philosophy to work out together ”and to settle accounts with their“ former philosophical conscience ”. The theses on Feuerbach and Die deutsche Ideologie are often considered to be those writings that for the first time contain the main features of the Marxian and Engelian materialistic-dialectical, critical theory.

The work on mutual understanding of theory was followed from 1847 onwards by the preparations for the Communist Party's manifesto (1848), which was commissioned as a program by the League of Communists and prepared in the program outline Principles of Communism (1847). After the defeated German Revolution of 1848/49 , Engels fled to England via Switzerland and spent the rest of his life there. He continued to publish writings that repeatedly dealt with social and societal issues, such as revolution and counterrevolution in Germany (1851 to 1852) or on the housing issue (1872).

Content presentations and key messages

The industrial revolution in England

The economic upheavals in England at the time of the industrial revolution in the 19th century led to social changes due to the division of labor , the use of water and especially steam power and mechanization . The industrialization of the economic sector in the transition from a manufacturing agricultural society to a manufacturing industrial society meant that most family manufacturing businesses in rural areas were facing the end. This development affected numerous trades; Engels describes them based on the weavers : Before industrialization, the weavers led a self-determined life near the cities, according to Engels. The women stretch the yarn that the men woven or that was sold in the market. The rapid population growth created a corresponding demand for textiles , so that the wages were sufficient to save money beyond securing a livelihood. As a result of these circumstances, the weaver was superior to the later industrial proletarian in the social hierarchy .

“In this way the workers vegetated in a very comfortable existence […], their material position was far better than that of their successors; they didn't need to overwork [...] and still earned what they needed [...] their children grew up in the open country air, and if they could help their parents with their work, it only happened now and then , and there was no question of eight or twelve hours a day. "

With the onset of inventions and mechanical improvements, the weavers' way of life was increasingly called into question. In 1764, James Hargreaves developed the Spinning Jenny in North Lancashire . One worker could operate up to 8 spindles at the same time instead of the one on the original spinning wheel . The mechanical power of the steam engine exceeded the manpower many times over and led to widespread unemployment , especially in rural areas, together with rising rents . At the same time, due to the new dimensions of production, especially in the case of food, an unparalleled population growth could take place.

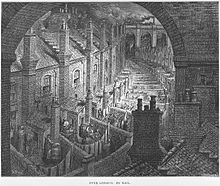

The unemployed people in the manufacturing trades, especially the weavers and spinners, saw the way out in the growing cities and the factories there with numerous jobs, and hundreds of them migrated to the working-class neighborhoods. These were created uniformly with a narrow road network and simple workers' houses such as the back-to-back houses . The cities changed their cityscape in the course of the centralization of industry with far-reaching consequences for the living conditions of the people and their coexistence as well as for the environment.

The proletariat

Systematization of the workforce

Engels subjects the workforce to a rough categorization, distinguishing between the industrial proletariat , the mining proletariat and the agricultural proletariat . The individual groups of proletarians are interrelated: the emerging industry requires workers who process raw materials - the industrial proletariat . On the other hand, the supply of the machines in the factories with fossil fuels had to be guaranteed, so that the mining proletariat had its own workforce. Due to the corresponding workload, both groups are no longer able to guarantee the self-sufficiency that was widespread in the past . The exploding demand for food gave rise to the agricultural labor force, which organizes the production of food and can carry it out on a large scale. In his study of the consequences of English industrialization, Engels also cites massive Irish immigration, which immigrated to English cities in such large numbers because of economic problems and the associated famine in their own country that Engels identifies them as separate workers.

The factory worker is described as a classic representative of the proletariat, who pays his labor in the factories of the cities through increasing unemployment in the countryside. This class was "the most numerous, oldest, most intelligent and most energetic, but therefore also the most restless and most hated of all English workers by the bourgeoisie". She found employment in numerous branches of work , especially in the textile and metal industries . In textile production, silk , wool and flax in particular were produced; their further processing brought workers as bleachers, stocking weavers, lace manufacturers, dyers, hand weavers, velvet cutters, silk weavers and printers to wages. In metal processing, in addition to processing metal raw materials, workers were usually employed as machine manufacturers or in the production of metal items such as knives, locks, nails, pins and jewelry. In addition to these widespread activities, work as a glass worker, seamstress or potter was common.

Social position and relationship to the bourgeoisie

Engels sees the mass of workers as the fundamental counterpart of the possessing bourgeoisie and, with his descriptions, substantiates the social approach of communism . The fundamental criticism describes capitalism as a centralized industry in the responsibility of only a few wealthy people. It requires "large capital, with which it builds colossal establishments and thereby ruins the small, artisanal bourgeoisie". Engels describes the middle class as the product of "small industry" and the working class as the result of "large industry", with some "chosen ones of the middle class on the throne". In his consideration of the bourgeoisie, Engels includes the aristocracy , although, unlike the haves, they only come into contact with the arable proletariat and part of the mining workers. The bourgeoisie is directly responsible for the suffering of the hard-working population. In bourgeois society, money-making or capital accumulation is the sun around which everything revolves.

“I have never seen a class so deeply demoralized, so incurably corrupted by selfishness, inwardly corroded and incapable of all progress as the English bourgeoisie. [...] For her there is nothing in the world that is not only there for the sake of money, not excluding herself, because she lives for nothing but to earn money, she knows no bliss but that of quick acquisition, no pain besides losing money. […] And if the worker does not want to be forced into this abstraction […] if he comes up with the belief that he does not need to be bought and sold as a commodity in the market, then the bourgeoisie has reason quiet. He cannot understand that he has a different relationship with the workers than that of buying and selling, [...] he recognizes no other connection, as Carlyle says, between man and man than payment in cash. "

All-round competition is the most perfect expression of the ruling war of all against all in bourgeois society. People not only competed between classes, but also within those classes. The relationship between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie is not a human one, but a purely rational economic one. The factory worker is nothing but capital for the capitalist; his hands his only good. Only through the employment of workers does the entrepreneur increase his capital, and he only buys workers if they bring him a profit. This implies that the wage of the worker fluctuates around the subsistence level - depending on whether there are periodic upsurges or crises and so there is more or less demand for labor among the capitalists - or he can find no work at all. "Beautiful freedom where the proletarian has no choice but to sign the conditions imposed by the bourgeoisie or - to starve, to freeze to death, to bed naked with the animals of the forest!" Engels describes the relationship as slavery and Exploitation ; man is reduced to the value of his labor power, which is determined like the value of every other commodity, and which is only bought if it is of use to the owner like any other commodity.

“The worker is legally and factually a slave to the possessing class, the bourgeoisie, so much so that it is sold like a commodity, as the price of a commodity rises and falls. If the demand for workers rises, the workers' prices rise; if they fall, they fall in price; If it falls so much that a number of workers cannot be sold, 'remain in stock', they just lie where they are, and since they cannot live by lying there, they die of hunger. [...] The whole difference to the old, open-hearted slavery is only that today's worker seems to be free because he is not sold all at once, but piece by piece, per day, per week, per year, and because not one owner sells him to the other, but he has to sell himself in this way, since he is not the slave of an individual but of the entire possessing class. "

Engels accuses the bourgeoisie of "charity hypocrisy". Instead of dealing with the living conditions of the workers, they buy the right to spare themselves the obvious suffering of the proletariat through charitable expenses such as taxes and alms . Their disregard for the workers is also evident in the question of the Corn Laws . In the clear support of the Anti-Corn Law League and the demand for the abolition of the Corn Laws, she sees only her own advantage, because wages would fall with the abolition of grain tariffs and the accompanying liberalization of the grain market. Outwardly, however, they propagated that the demands should only be made for the benefit of the workers, who could expect lower food prices with the abolition of grain tariffs.

In addition to individual large industrialists , the “judiciary of the bourgeoisie” was also partisan and degrading towards the poor. While a property owner could settle his guilt with a fine, the worker, guilty or innocent, would face a penalty for lack of evidence. Engels continues to criticize Malthus's theory of population , which states that the human race blindly obeys the law of unlimited reproduction, while means of subsistence do not necessarily reproduce with the same proportions. The "superfluous" people thus created are not to be sought on the part of the workers, but among the "rich gentlemen capitalists who do nothing [...]". The resulting New Poor Law , according to which the support is eliminated in money or food and by inclusion in one of the workhouses (Engl. Workhouses ) is replaced is a disgrace to humanity .

Working-class district

Although whole working-class quarters emerged as the cities expanded , there was a shortage of housing . When building the accommodation, the building owners only considered the function of living to be worthwhile; there was no question of later urban sociological achievements such as the garden city . The lack of water supply and sewerage and the space-saving, efficient construction made the districts dark, damp and unsanitary. Engels sees the main reason for the conditions in the districts in their general design. Engels describes the initially haphazard, later structured, but always not liveable building forms as an endless labyrinth of narrow streets that leave hardly any room for ventilation and stand in stark contrast to bourgeois living conditions - Engels sees the increasing segregation of bourgeoisie and working class as an essential characteristic.

General design

Engels describes three different building structures. The first and most primitive form of development was often uncoordinated, without worrying about city and infrastructure across all blocks, and fitted into free building areas. Engels does not see the cityscapes he found as the result of ongoing urban development , but instead names the influx of workers in the course of the industrial revolution and the associated haphazard construction as the cause.

"[...] the confusion has only been driven to extremes in recent times, in that wherever the whole design of the earlier epoch left a little space, it was later rebuilt and patched until finally there was not an inch of space between the houses, which could have been built. "

Orderly construction methods were also established later, characterized by long straight alleys and dead ends and divided into square courtyards. However, Engels describes that instead of the houses that determine the structure without a plan, the small alleys and courtyards now shape the picture. These are just as haphazard and confusing and often end in dead ends. This type of construction also makes ventilation in the streets difficult.

As a second type of structuring, Engels cites later efforts to make the working-class quarters more systematic. An attempt was made to divide the space between the streets more regularly by dividing it into rectangular spaces. The houses thus also form courtyards and define these where they touch at the rear. But Engels also criticizes this type of planning. The courtyards of the houses have no direct access to the street, which “locks” the workers in their courtyards and in turn hinders the flow of air.

As a third type of building, Engels describes the three-part construction method, where the principle of rent differentiation is applied. Apartments with a small backyard per rental unit form the first series with correspondingly higher rental income for the manager. Behind the courtyards there is a so-called “back alley”, which only has a connection to the street and thus only serves as access to the houses with the lowest rents (middle row). The rear of the street is bordered by the third row, which faces the opposite side of the street and whose rents are higher than those of the second, but lower than those of the first row.

Above all, the living conditions of the residents of the middle row make Engels pensive. The alleys show the same pollution and poor ventilation as the originally haphazard construction. However, he sees an increased interest on the part of the administrators in the principle of rent differentiation, as they can achieve high rents for the first row. Accordingly, this system is the most frequently used in the working-class districts of large industrial cities .

"[...] we must say that three hundred and fifty thousand workers in Manchester and its suburbs almost all live in bad, damp and dirty cottages, that the streets they occupy are mostly in the worst and most unclean condition [...], just have been invested in consideration of the profit accruing to the builder [...] "

segregation

The relationship between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie shown here reveals a new quality of segregation for Engels in the course of industrialization . Already in the pre-industrial city, the separation according to social class and skilled trades was the rule. The dispossessed lived in the house of their rule, where they belonged to the social class of the head of the family; the household itself spanned a wide social spectrum. It was only with the onset of industrialization that clear patterns of spatial segregation emerged: while the bourgeoisie kept their distance from the densely populated, busy and noisy city, working-class quarters for the proletariat formed near the factories. Engels describes the social consequences in gloomy descriptions and describes the occurrence of neighborhood effects (social segregation): Under these circumstances the workers could not lead a decent life; rather, a lumpen proletariat is forming , which, if there is a lack of morality, pulls the residents down, as it were. This especially affects the children, who have no chance of education and social advancement, so that a vicious circle of eternal poverty arises.

In addition to the effect of spreading disease, Engels saw the neighborhood as a hotbed of the revolution. In the working-class quarters, the propaganda of the workers' movements and parties can be communicated directly and at the same time encounter the breeding ground of oppression and impoverishment . The bourgeoisie turn a blind eye to this. In this way it is possible to stroll through Manchester without encountering the misery of the working-class neighborhoods because the proletariat is deliberately separated from the middle class. In the center of the city is the sparsely inhabited commercial district, which is surrounded by working-class neighborhoods. Beyond the working-class neighborhoods, the residential areas of the middle and upper bourgeoisie are connected by main streets that lead out of the city in a star shape. This allows the bourgeoisie to reach the center of the city without burdening themselves with the sight of neglect .

“Often, of course, poverty lives in hidden alleys close to the palaces of the rich; but in general she has been assigned a separate area where she, banished from the eyes of the happier classes, can get by with herself as best she can. "

living conditions

The unattractive housing situation in the working-class neighborhoods meant for the proletariat at the same time a severe cut in the general quality of life , which by today's standards can be compared with the conditions in third world countries . The situation in the working-class districts is partly responsible for the catastrophic health and hygiene conditions. Combined with the inadequate supply of clothing and food and the overcrowding of living space resulting from the lack of housing, the districts advanced to become pauperistic slums . For Engels, the working class of the big cities presents itself in different living situations. In the best case, the worker leads a “temporarily bearable existence”, in the worst case there is a threat of bitter misery “up to homelessness and starvation [...] but the average is far in the worst case closer than the best. ”Engels sees mass poverty as a logical consequence of industrialization. Indeed, industrialization also attracted poor people.

The social grievances of the working-class neighborhoods were not to be viewed critically until the social question was raised at the end of the 18th century. While the social question was already posed at the beginning of the industrial revolution by the growing population, the decline of the old trades and the emergence of the factory industry, it is now the existential need of the workers and the rampant pauperism that require a solution. Due to the working conditions, women's and child labor and, in particular, the housing situation, the question of the equitable distribution of prosperity arose again and again during the industrial revolution. The dissolution of social networks, the poor working conditions, the inadequate housing situation, the inadequate social integration of the workers, the disregard for the bourgeois public and the impoverishment were criticized in particular . In addition to Engels there were impulses from science in which the situation of society was presented in a well-founded manner using facts and factual reports. However, no specific questioner can be identified. Instead of asking “who?” Rather, “where from?” And “why?” Should be asked; the answers to these questions are presented below. Engels later made the social question the question of housing, in that he identified the cause of the poor living conditions of the workers primarily in the poor condition of the apartments and working-class neighborhoods.

Housing conditions

Engels describes the conditions in the apartments in the slums using police reports and official notices as an example, depending on the external circumstances. The home furnishings are mostly limited to the sparse, partly because furniture and objects have to be sold for money; even having a bed or table is the exception. The worker himself has next to no property . In most cases the apartments are acutely overcrowded due to the housing shortage. For Dublin , Engels cited a report by the workhouse inspectors, according to which in 1817 there were 52 houses with 390 rooms in Barrack Street and 1,318 people in Church Street and the surrounding area in 71 houses with 393 rooms. This results in an occupancy of three to five people per room, i.e. about one family per room. In view of the significantly higher occupancy in Glasgow , for example , this seems almost humane. For Liverpool, Engels names the basement apartments that are widespread due to the housing shortage , of which there were 7,862 in Liverpool alone . Around 45,000 people live in the “narrow, dark, damp and poorly ventilated cellars”. The rental of back rooms and chambers was also common. Those who were not given permanent accommodation could only stay in one of the lodging-houses , which were also overcrowded.

“[...] In the lower lodgings, ten, twelve, sometimes even twenty people of both sexes and of all ages sleep in different degrees of nudity on the floor. These dwellings are usually [...] so dirty, damp and dilapidated that nobody would want to put their horse in them. "

At the same time, the cramped living space makes social coexistence difficult. Family breakdowns, domestic disputes and the general living and living situation had a "highly demoralizing effect" on the spouses and children . Engels accuses parents of neglecting domestic duties and children, on the one hand because of the dominance of everyday work and on the other hand because of the aforementioned demoralization . Children who, in view of the lack of opportunities to retreat, lack any scope for personal development and who are not taught any morals , could certainly not be moral in adulthood , as is assumed by the bourgeoisie.

Engels does not infer from the exemplary observations on the totality of the workers, but admits that "Thousands of hard-working and good families, much more well-behaved, much more honorable than all the empires of London, are in this unworthy position of a human being".

Diet and clothing

Part of the responsibility for the devastating situation is the lack of clothing and food , which in turn is due to the proletarian shortage of money. Engels describes the clothing of the workers as "in very bad condition". It is characterized by cheap cotton , the nature of which Engels finds unsuitable in the humid English climate . For the workers, getting rid of the ragged, tattered clothes means having to buy inferior new goods that “are only made to sell, not to be worn” and which tear or become threadbare after a fortnight ”. Often the workers have no choice but to mend clothes over and over again, "which are often no longer mendable or where the original color can no longer be recognized because of all the patches". On footwear must be largely dispensed with entirely.

As with clothing, when it comes to food, the working population also has to be content with “what is too bad for the possessing class”. Although the best was available in abundance in the big cities, it remained unaffordable for the worker. The workers' wages are usually not paid until Saturday evening, when the markets have already been bought empty by the middle class. Engels even assesses staple foods such as potatoes , vegetables , cheese and meat as "old [...] and already half lazy". The workers usually only have goods that are sold at ridiculous prices until midnight on Saturday, since they are bad until the following Monday. "But what was left behind at ten o'clock, nine tenths of it is no longer edible on Sunday morning and it is precisely these goods that make up the Sunday table of the poorest class." The supply of sensitive meat products in particular proves to be extremely problematic; Engels uses newspaper reports to describe the profit-oriented trade in rotten meat . He also reports on counterfeit goods, for example by quoting a report in the Liverpool Mercury, a middle-class newspaper. Accordingly, in the face of the food shortage, workers would have to " expect salted butter [which] is sold for fresh". Sugar is mixed with crushed rice and soap-making waste . Ground coffee and cocoa are mixed with fine brown earth, tea leaves with sloe leaves and pepper with dust from pods. Port wine is "virtually manufactured" mainly from colorants and alcohol.

working conditions

In the factories, where people eke out their existence day in and day out, the workers are no better off. They would have to work at the lowest wage level , since there is an oversupply of labor due to the massive rural exodus. In addition, there are disproportionately long working hours of up to 16 hours in shifts and sometimes also in night work , even Sunday is not a day off for everyone. Engels names the situation as follows: “The slavery in which the bourgeoisie keeps the proletariat shackled is nowhere more clearly exposed than in the factory system. This is where all freedom legally and factually ends. "

Work in the factories is perceived by the workers as "easy", but according to Engels it is "slacker than any other because of its lightness." Constant standing means a relaxation "of all body forces and [brings] in their wake all sorts of other less local than general evils". Since the workers are forced to accept any work for reasons of existence, the bourgeoisie can afford to provide any working conditions with regard to health, with corresponding consequences. Engels describes day-to-day work as despotic: the workers would have to strictly adhere to the arbitrarily set factory rules and expect severe sanctions if they were not complied with. Since the women also worked full-time in the factories, Engels asks the question, “What should become of the children?” Engels sees the family dissolving and the children “grow up wild like weeds”. The bourgeoisie knows the answer and sends the pubescent children to the factories too. With their skilled hands, they revealed skills that the ordinary worker could not offer. Sometimes entire groups of children from the poor houses are hired out as "apprentices" for years. The children are especially under the dictates of the supervisors, Engels speaks of abuse .

Health condition

The heavy physical activity in the factories was accompanied by long-term health problems. The human body gave up under the physical and psychological strain in the metalworks or the textile factory: The "permanent upright position, this constant mechanical pressure of the upper body on the spine , hips and legs necessarily brings about the consequences mentioned." Reports by the commission reveal a whole series complaints such as "[...] swollen ankles, varicose veins or large, stubborn ulcers on the thighs and calves". Engels also criticizes the air in the factories: "[...] humid and warm, usually warmer than necessary, and if the ventilation is not very good, very unclean, dull and low in oxygen, filled with dust and the haze of machine oil." The regular ones Temperature changes after work and the lack of opportunities to change clothes would do the rest. For women, Engels paints an even worse picture, the "deformities [...] become even more serious with women". Deformed pelvis , "partly due to incorrect position and development of the pelvic bones themselves, partly due to the curvature of the lower part of the spine " are common and lead, for example, to factory workers giving birth more difficultly than other women.

The living conditions shown inevitably result in a high health risk for the working population and, associated with this, a low life expectancy . Engels sees the inadequate air circulation in the neighborhoods and the fact that “three and a half million lungs and three and a half hundred thousand fires, concentrated on three to four geographical square miles, consume an enormous amount of oxygen” as the cause of “physical and mental slackening and depressing of vitality” Lack of oxygen . However, this statement must be viewed critically: the breathing of the urban population may have played its part. The uneasiness of the people probably resulted from the generally bad air. Engels draws a comparison with the rural population, who live in a "free, normal atmosphere" and therefore healthier than the urban population.

The lack of water is still partly responsible for the health of the workers. Pipes are only laid against payment and "the rivers are so polluted that they are no longer suitable for cleaning purposes". By already aware of the construction of the quarter largely due to toilets and waste containers is dispensed with, the workers are forced to "all waste and garbage, all dirty water, and often all disgusting filth and manure on the road to pour". For Engels, the health of the workers is the result of a multitude of factors, all of which stem from the oppression of the proletariat.

“They are given damp apartments, basement holes that are not watertight from below, or attic chambers that are not watertight from above. Their houses are built so that the dull air cannot escape. They are given bad, ragged or ragged clothes and bad, adulterated and indigestible food. You expose them to the most exciting changes of mood [...] - you chase them down like wild animals and don't let them come to rest and enjoy life in peace. You deprive them of all pleasures except sexual pleasure and drinking, but work them off daily until all mental and physical forces are completely exhausted. "

It is quite logical that the conditions must lead to far-reaching diseases and epidemics . Engels reports that the workers are often affected by lung diseases , which mainly resulted from the adverse air conditions in the neighborhoods. He notices that in the morning he encounters a noticeable number of “consumptive-looking people”. In addition to tuberculosis , other lung diseases and scarlet fever , typhus is widespread, which "causes the most terrible devastation among the workers". The disease regularly swells into epidemics; In 1842, one sixth of the total workforce in Scotland was attacked. Engels attributes the vulnerability of workers to the disease, among other things, to inadequate medical care for the poorer population. The lack of wholesome foods made many people crippled . Missing vitamins , nutrients and minerals led to curvature of the spine and legs, according to a report by the commission. Children between the ages of 8 and 14 in particular would develop rickets more , although children at this age "are usually no longer subject to rickets".

Labor movements

For Engels, the logical consequence of the relationships presented is a revolt of the working class. He speaks of "open social war ", which he sees as a reaction of the workers to the exploitation by the ruling class.

“The workers must therefore strive to get out of this losing position […] and they cannot do this without fighting the interests of the bourgeoisie […]; The bourgeoisie, however, defends its interests with all the forces that it is able to use through its property and the state power at its disposal. As soon as the worker wants to work his way out of the current situation, the bourgeois will be his declared enemy. "

Engels dates the emergence of labor movements shortly after the beginning of the industrial revolution. He divides this into three phases. First of all, he calls the "crime", the individual protest by means of theft . Engels describes this as "raw" and "sterile" and at no time as the "general expression for the public opinion of the workers". According to Engels, the first serious oppositional attacks on the bourgeoisie consisted of the beginnings of violent protests and sabotages , the machine storming directed against what made the “oppression” possible, the machines and factories. However, Engels describes these protests as isolated and too local, but above all as too limited, since they were directed exclusively against “one side of the current situation”.

As a clear consequence, Engels argues for a more sustained form of opposition, which should be formative for the third phase of the labor movements. This was helped by a law that was passed in 1824 and gave workers the “right of free association”, that is, the right of assembly. This favored the expansion and further development of the already existing connections, which until then had only acted in secret and thus could not develop sufficiently. Such associations, the so-called trade unions , arose in every branch of work . These were primarily aimed at regulating wages and the interests of workers. The power of the strike proved to be the only weapon to call for them . This is what Engels calls the common opposition to arbitrary wage cuts by manufacturers in the wake of demanding competition . However, Engels describes the history of the trade union rebellion primarily as "a long series of defeats".

“These strikes are [...] first outpost skirmishes, sometimes also more important skirmishes; they decide nothing, but they are the surest proof that the decisive battle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie is approaching. "

Engels sees the union ideas of Chartism as a promising further development of existing protests and thus the basis of an independent British labor movement, which, however, also falls short of the requirements of modern socialism . Chartism advocated the People's Charter (Engl. People's charter ) one, so for the Law of the proletariat. It is to be understood as an opposition to the bourgeoisie and calls for the six central points of the People's Charter :

"1. The universal right to vote for every man of age convicted of sound mind and no crime; 2. Parliaments to be renewed annually; 3. Diets for members of parliament so that the poor can also accept an election; 4. Ballotage elections to report bribery and intimidation by the bourgeoisie; 5. Equal electoral districts in order to ensure cheap representation, and 6. Abolition of the - already illusory - exclusive eligibility of those who own £ 300 in real estate, so that every voter can also be elected. "

The importance of these six demands was beyond question for Engels, so they would be enough to shake the foundations of the English classes. The Chartists wanted to get it through at all costs. Engels also addresses the social aspect of the Chartism movement, which in its understanding sees itself as predominantly political. So it was not just about political participation . Above all, this should serve as a means to bring about the real purpose, a fundamental change in the existing order.

According to Engels, the initial difficulties of the labor movements are supplemented by general problems of the new industrial society . The law of supply and demand would not be able to cope with major changes in the labor market , such as crises. But despite all this, strikes are the order of the day, which Engels proves that the social war has already gripped England to an astonishing extent. This leads to greater expectations, namely the social question already formulated, which inevitably leads to social war.

Reception and aftermath

Engels' later assessment

In the foreword to the English edition of 1892, Engels himself admitted that the work bears “the stamp of youth in good and bad”. He also noted that the “general theoretical standpoint of the book - in philosophical, economic and political terms - by no means exactly coincides” with his views in 1892, 47 years after publication. He stressed, however, that the text had not been deleted or changed in later editions, not even in relation to the "imminent social revolution in England" according to Engels, a forecast that he had later revised. Instead of adapting the text to current events, for developments after 1844 he referred to the first volume of Marx's Capital “with a detailed account of the situation of the British working class for the period from about 1865, that is, the time when British industrial prosperity was at its height reached ”. At the same time he admitted that he had “sharpened some not very clear passages”. Engels stated in the same preface that some predictions have come true. In particular, that the position of English industry would be weakened in the near future as a result of continental and especially American competition. Although this fact came to fruition a little later, it still happened as I said. Engels felt obliged to bring the book in line with the state of affairs at the time: In the foreword, an article is quoted that was published in the London Commonweal of March 1, 1885 under the title England 1845 to 1885 .

Content and methodological criticism

Later reviews were particularly bothered by Engels' bias: He had come to England to find a country that was ready for the socialist revolution - and he found it. By addressing directly “To the working classes of Great Britain”, he took a concrete position - “unforgivable for a sociologist”, as Günter Wallraff pointed out. However, Engels' careless handling of prognoses was criticized by others: in addition to the false prognosis of an impending revolution, the prognoses about a growing gap between rich and poor, as well as the statement about the necessity of child labor, were not fulfilled. There was also criticism from a technical point of view, for example at Engels' romanticizing portrayal of the pre-industrial life of homeworkers : In 1848, the Marburg political scientist Bruno Hildebrand criticized that it was not the existence, but rather the lack of modern factory industry that caused the greatest material hardship.

In addition, Engels was accused of being "buried up to his ears in English newspapers and books" and thus reporting on the situation of the English proletarians. This is not field research in the strict sense of the word: the essentials are "derived from a relatively small documentation" and it is not made clear to the reader to what extent what is presented was based on their own observations. In addition, Engels did not provide out-of-date information with dates for classification, and where information was only available second-hand, the impression would sometimes be created that Engels was referring directly to original sources. Engels himself speaks of an "abbreviation or distortion of the original". These inaccuracies - also with regard to the handling of statistical data - are probably due to Engels' intention, which was more philosophical than empirical in nature. In fact, contrary to the specifications of the text, there are contemporary statistical surveys and journalistic interviews with regard to the circumstances at the time, which do more justice to the topic from a scientific point of view. However, it was noted that it would be "a misunderstanding to see it [the scripture] as a scientific monograph." Instead, the work is "a criticism of what he [Engels] describes, an indictment". Here write “no scientist who coldly dissected and analyzed his object of investigation, but the coming homme révolté , who is his j'accuse! (I accuse!) hurled at his audience with persuasiveness ”.

"Criticism in the scuffle"

The central type of criticism by Marx and Engels was developed and applied primarily by Marx in Das Kapital (1867). Its specialty is to form a methodical unit from analysis, presentation and criticism. In Das Kapital , Marx used a further type of critic, the methodology of which can be found in Basic Features in The Situation of the Working Class in England . Engels worked there to lay the foundation for a so-called scuffle critique or another critique of political economy . This second type can be found in Capital apart from the "main analytical lines [...] in the subsidiary sections and excursions [...] where Marx [...] wants to illustrate, but above all to create the effect of fright, incomprehension and the unbelievable". With this criticism in the scuffle there "not whether the opponent is a [...] go more interesting is," but "a question of him hit " by a "specific method of escalation" get used to "rhetorical, performance character". A central aspect of the critic type is that Engels wants to "beat the liberal bourgeoisie out of their own mouth", which is why he makes particular use of bourgeois material, be it in the form of official reports or scientific studies. On the one hand to maintain credibility in front of the bourgeois audience, on the other hand to hold up a mirror to the bourgeoisie.

Allegations of plagiarism

In 1906 the anarchist Pierre Ramus charged that Friedrich Engels had copied from the book “La misère des classes laborieuses en Angleterre et en France” by Eugène Buret from 1840 without any identification , and this was proven by various quotations. Further plagiarism was documented in the English new translation by WO Henderson and WH Chaloner, for example a paraphrase over several pages in the introduction, which was taken from Peter Gaskell's book "The Manufacturing Population in England" from 1833 without any indication.

expenditure

- The situation of the working class in England . Verlag Otto Wigand, Leipzig 1845. 2nd edition Leipzig 1848.

- The situation of the working class in England . Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA) Dept. 1., Volume 4. Marx-Engels-Institut. 1932/1970.

- The situation of the working class in England . Marx-Engels-Werke (MEW) Volume 2. Dietz, Berlin 1972. pp. 225-506.

- The situation of the working class in England . Marx-Engels Complete Edition 2 (MEGA²), unpublished.

literature

- Matthias Bohlender : "... to beat the liberal bourgeoisie out of their own mouth" - Friedrich Engels and criticism in the scuffle . In: Marx-Engels-Yearbook 2007 . Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2008.

- Auguste Cornu : The development of historical materialism in Marx's theses on Feuerbach, Engels' The situation of the working class in England and in the German ideology of Marx and Engels. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1967.

- Wolfgang Mönke : The literary echo in Germany on Friedrich Engels' work The situation of the working class in England. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1965.

Web links

Further primary texts

- Friedrich Engels: The situation of the working class in England. Second edition. Otto Wigand Leipzig 1848. (Google Books)

- Friedrich Engels: The situation in England , in: German-French year books . Paris 1844. MEW 1, pp. 525-549.

- Friedrich Engels: Retrospective on the situation of the working classes in England , in: Das Westphälische Dampfboot , Bielefeld 1846. January issue p. 17–21, February issue p. 61–67, MEW 2, p. 591–603.

- Friedrich Engels: Letter to Florence Kelley Wischnewetzky , London, February 3, 1886, quoted from Science and Society Volume II, Number 3, 1938.

reception

- Lothar Peter : The situation of the working class in England . In: Georg W. Oesterdiekhoff (Ed.): Lexicon of sociological works , VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2001.

- Günter Wallraff : The situation of the working class in England . In: Die Zeit , July 22, 1983 No. 30.

Individual evidence

The page numbers of the quotations and individual references to Engels refer to Friedrich Engels: Situation of the working class in England . 1845, MEW . Dietz, Berlin 1972. Volume 2. pp. 225-506.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Matthias Bohlender: "... to beat the liberal bourgeoisie out of their own mouth" - Friedrich Engels and criticism in the scuffle. In: Beatrix Bouvier , Galina Golovina, Gerald Hubmann (eds.): Marx-Engels-Jahrbuch 2007 . Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2008. P. 9ff.

- ^ A b c d e Lothar Peter: The situation of the working class in England . In: Georg W. Oesterdiekhoff (Ed.): Lexicon of sociological works . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften , 2001.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 325.

- ↑ Josef Rattner, Gerhard Danzer: The Young Hegelians - Portrait of a progressive intellectual group . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005. p. 194. - Orwell took up elements of Engels' in his work Der Weg nach Wigan Pier (1937), in which he describes the social conditions in the mining town of Wigan near Liverpool.

- ↑ a b c d e Josef Rattner, Gerhard Danzer: The Young Hegelians - Portrait of a progressive intellectual group . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005. pp. 189f.

- ^ A b Günter Wallraff: The situation of the working class in England . In: Die Zeit, July 22, 1983, No. 30.

- ↑ Fabian Kessl, Christian Reutlinger (Ed.): Key works of social space research - lines of tradition in text and contexts . VS publishing house for social sciences. Wiesbaden 2008. pp. 189f.

- ↑ In the Marx-Engels works , the font takes up about 270 pages.

- ↑ Matthias Bohlender: "... to beat the liberal bourgeoisie out of their own mouth" - Friedrich Engels and the criticism in the scuffle . In: Marx-Engels-Jahrbuch 2007. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2008. p. 26.

- ↑ Above all, James Phillips Kays The moral and physical condition of the working classes (1832), Peter Gaskells The manufacturing population of England (1832) and Archibald Alison's The principles of population, and their connection with human happiness (1840) should be mentioned here.

- ^ Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Manifesto of the Communist Party . In: MEW. Vol. 4. p. 473. Ed .: MB.

- ↑ Engels, The Situation of England, MEW 1: 525-549.

- ↑ a b cf. Engels, 1845, p. 232f.

- ^ Sven Papcke, Georg W. Oesterdiekhoff (ed.): Key works of sociology . West German publishing house. Wiesbaden 2001. pp. 143ff.

- ↑ “I will put together a fine register of sins for the English; I accuse the English bourgeoisie before the whole world of murder, robbery and all other crimes en masse… ”; Engels, letter of November 19, 1844 to Marx, MEW 27:10.

- ↑ Engels, p. 506.

- ↑ Engels p. 233; "Incidentally, it goes without saying that I hit the sack and mean the donkey, namely the German bourgeoisie, to which I say clearly enough that they are just as bad ... just not so courageously, so consistently and so skillfully in their drudgery." Engels, Letter of November 19, 1944 to Marx, MEW 27:10.

- ↑ Quoted from Karl Marx. In: Marx-Engels-Werke, Volume 13.P. 10.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 254.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 238.

- ↑ Annual population increase in England (19th century): 1.23 percent. In: Jürgen Osterhammel: The transformation of the world. A story of the 19th century . Munich, 2009. p. 191.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, pp. 253f .; P. 456f .; P. 473f.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 360.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 417.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, pp. 254f.

- ↑ cf. Thomas Carlyle: Past and Present . London, 1843.

- ↑ Engels, p. 307.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 486f.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 489f.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 491.

- ↑ by Thomas Robert Malthus: Essay on the Principle of Population . 1798. In: "Population (Malthus theory etc.)." From Meyers Konversationslexikon, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig and Vienna, fourth edition, 1885-1892.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, pp. 494f.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 276.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 281.

- ↑ a b cf. Engels, 1845, pp. 287f.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 288.

- ↑ Hildegard Mogge-Grotjahn: Handbook of poverty and social exclusion . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2008. p. 337.

- ↑ cf. Hartmut Häußermann, W. Siebel: Sociology of living. An introduction to change and differentiation in living . 1996.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 279.

- ↑ a b c cf. Engels, 1845, p. 304.

- ↑ Hildegard Mogge-Grotjahn: Handbook of poverty and social exclusion . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2008. p. 238.

- ↑ Engels: On the question of housing . “The People's State”, Leipzig 1872.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 262.

- ↑ Quoted in Dr. WP Alison: Observations on the Management of the Poor in Scotland and its Effects on the Health of Great Towns . Edinburgh 1840.

- ↑ a b cf. Engels, 1845, p. 266ff.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 270.

- ^ JC Symons: Arts and Artizans at Home and Abroad . Edinburgh 1839. pp. 116f. Quoted in: Engels, 1845: p. 270.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845: p. 356.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845: p. 263.

- ↑ a b c d cf. Engels, 1845, p. 297ff.

- ↑ a b cf. Engels, 1845, p. 374ff.

- ↑ a b cf. Engels, 1845, p. 398.

- ↑ a b cf. Engels, 1845, p. 378.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 368.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 383.

- ↑ a b cf. Engels, 1845, p. 325f.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 272.

- ↑ a b cf. Engels, 1845, p. 327f.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 376.

- ↑ a b c d e cf. Engels, 1845, p. 431f.

- ↑ a b cf. Engels, 1845, pp. 444f.

- ↑ cf. Engels, 1845, p. 434.

- ↑ a b c Preface to the English edition. London, January 11, 1892.

- ^ Foreword to the 2nd German edition. Stuttgart, July 21, 1892.

- ^ A b Gustav Mayer: Friedrich Engels - A biography . The Hague, 1934. In: Ossip K. Flechtheim : From Marx to Kolakowski . EVA, 1978. p. 120.

- ↑ Helmut Hirsch : Engels . rororo, 1968.

- ↑ cf. Wilhelm Abel: Mass poverty and hunger crises in pre-industrial Europe. Attempt a synopsis . Hamburg, Berlin 1974. pp. 305f. In: Hildegard Mogge-Grotjahn: Handbook of poverty and social exclusion . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2008. p. 238.

- ↑ Helmut Hirsch: Engels . rororo, 1968. p. 39.

- ↑ Helmut Hirsch: Engels . rororo, 1968. pp. 40f.

- ^ Ossip K. Flechtheim: From Marx to Kolakowski . EVA, 1978. p. 53.

- ↑ Karl Marx: On the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right . Paris 1844. p. 74.

- ↑ See "Friedrich Engels as a plagiarist." In: The Authorship of the Communist Manifesto. (online) ( Memento from January 31, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 440 kB)

- ^ Friedrich Engels: The Condition of the Working Class in England (translated and edited by WO Henderson and WH Chaloner). Stanford University Press, Stanford 1958. Pages 9-12 footnotes.