Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (1875)

The Socialist Workers' Party of Germany ( SAP ) was a socialist party in the German Empire . It was created in 1875 from the merger of the Social Democratic Workers 'Party (SDAP) and the General German Workers' Association (ADAV). Its history was shaped between 1878 and 1889 by the effects of the Socialist Law . After its end, the party was renamed the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in 1890 , as it is still called today.

Gotha Unification Party Congress

With the SDAP of August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht and the ADAV, which was founded by Ferdinand Lassalle in 1863 , there were initially two workers' parties. They differed in various details, but what was decisive was the difference to the national question. While the ADAV was oriented towards small German-Prussian, the SDAP was oriented towards greater German. With the founding of the empire in 1870/71, these contradictions had become obsolete. Instead, there were more similarities than differences in daily politics, especially in the Reichstag . In addition, the pressure of the anti-social democratic measures of the authorities contributed to further rapprochement. Everything together led to the establishment of a joint program commission and ultimately to the unification of both organizations. The unification party convention of the Marxist " Eisenachers " (after the founding place of the SDAP) with the more moderate "Lassalleans" took place from May 22nd to 27th, 1875 in Gotha . At that time the ADAV had 15,322 members and provided 74 delegates, the SDAP had 9,121 members and provided 56 delegates.

The SAP Gotha program was also adopted at the unification convention. In terms of content, this was a compromise between the two original parties. It contained elements of both the SDAP and the ADAV. In the first paragraph it said:

“In today's society the means of labor are monopolies of the capitalist class; the resulting dependence of the working class is the cause of misery and servitude in all forms. The liberation of work requires the transformation of work equipment into the common good of society and the cooperative regulation of the overall work with charitable use and fair distribution of the labor yield. The liberation of labor must be the work of the working class, against which all other classes are only a reactionary mass. "

Then in the second paragraph:

“Proceeding from these principles, the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany strives with all legal means to achieve the free state and socialist society, the breaking of the iron wage law by abolishing the system of wage labor, the abolition of exploitation in all forms, the abolition of all social and political inequality . "

While the appeal, for example, to the iron wage law came from the ADAV fund, the local program expanded in a second part largely corresponded to the ideas of the Eisenachers. Karl Marx immediately criticized the program in his criticism of the Gotha program and claimed that the "Lassallean sect" had triumphed. However, at the request of the party executive, this article was not published until 1890. August Bebel pointed out to the criticism that it was not the theoretical ambiguities but "the fact of the agreement that is the main thing".

The highest organ of the new party was the party congress, which not least had to elect the party executive. In these, based in Hamburg , Wilhelm Hasenclever , the former chairman of the ADAV and Georg Wilhelm Hartmann of the SDAP were elected as chairmen with equal rights. August Geib was the cashier . Ignaz Auer and Carl Derossi were secretaries. August Bebel became chairman of the control commission . A total of 3 former Lassalle supporters and 2 "Eisenachers" were represented on the board.

In addition to the program, the relationship with the trade unions in Gotha was discussed. Its establishment was said to be necessary because it promoted the workers' cause. Immediately after the unification congress, a trade union congress followed, which decided to merge the previous local associations into central associations. The principle of political neutrality was adhered to, but the members were asked to join the new party.

Development up to the socialist law

The new party was closely monitored by the authorities from the start and hindered in its work. As early as March 1876, the public prosecutor under Tessendorf applied for the party to be banned within the scope of the Prussian law on associations, and especially the organization in Berlin. Due to the impending ban, the party congress of 1876 also operated as the General Socialist Congress. At that time, the party had about 38,000 members in 291 locations. It had 38 newspapers and magazines. These included 21 local papers, as well as eleven union papers, an entertainment paper and three joke papers. The Congress decided to merge the former party organs of SDAP and ADAV, the People's State and the New Social Democrat . From October 1, 1876, the Vorwärts appeared as the party's new central organ. The leading editors were Wilhelm Liebknecht and Wilhelm Hasenclever . Due to the political persecution, a five-member central election committee with almost unlimited powers was elected to replace the board. The seat of the committee was Hamburg. There was a seven-person audit and control commission based in Bremen for control purposes.

In the Reichstag election of 1877 , the party ran in 175 constituencies and received over 490,000 votes, which corresponded to 9.1% of the votes. The party had thus received 36% more votes than the two previous parties combined in the last Reichstag election. The party had become the fourth strongest political force in terms of number of votes. However, due to an unfavorable constituency division, it only had twelve members of the Reichstag. Other data also make it clear that, despite the reprisals, the party had considerable traction. The liberal politician Ludwig Bamberger stated that the social democratic party papers had over 135,000 subscribers.

On May 11, 1878 in Berlin, the journeyman plumber shot Max Hodel on William I took this as Otto von Bismarck as an opportunity to bring an emergency law against social democracy on the way. However, this draft was approved by a large majority in the Reichstag on 23/24. May rejected. On June 2, Karl Eduard Nobiling committed another assassination attempt on the Kaiser, in which Wilhelm was seriously injured. Immediately afterwards, extensive agitation against the Social Democrats began. Only a few days after the attack, the Reichstag was dissolved, because Bismarck hoped that the impact of the events would strengthen the proponents of an exceptional law. In addition to the fight against social democracy, the circumstances of the election were a welcome opportunity to push ahead with the conservative turnaround in domestic politics. In the elections in 1878 , however, it became apparent that only slightly fewer votes were cast for the SAP than in 1877. The party had nine members. In view of the anti-social democratic measures that were already beginning, this was a considerable success. However, the liberals, and with them the critics of exceptional legislation, lost 39 seats.

After the completion of the first reading of a new draft law, the leaders of the parliamentary group and party discussed the future path in Hamburg. After heated debates, the party's self-dissolution was decided before the law came into force. Nevertheless, a central office based in Leipzig remained. The party's leaders rejected excessive actionism. "Don't let yourself be provoked!" Was appealed to the members and "our enemies must perish because of our legalism."

Under the socialist law

Effects and Limits of the Law

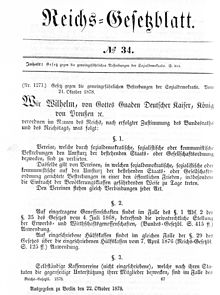

On October 19, 1878, the Reichstag adopted the law against the dangerous efforts of the Social Democrats (known as the Socialist Law for short ) with 221 votes against 149 votes from the Social Democrats, the Center and the Progress Party . After that, clubs and associations of all kinds, printed matter, meetings and money collections could be banned. Agitators could be expelled from certain areas and business permits withdrawn for certain groups. However, Otto von Bismarck failed in parliament with the attempt to deprive the Social Democrats of active and passive voting rights. The law was initially limited to 1881, but was subsequently extended regularly.

The Social Democratic Party was finally pushed underground for twelve years. Its party organ, the Vorwärts , was banned, as were public appearances or meetings of the party. Only two of the party's newspapers were not banned because they were politically neutral. The unions were also banned. Only the Reichstag faction of the SAP, to which Wilhelm Liebknecht, August Bebel and Wilhelm Hasenclever belonged, kept their seats. Many party members were forced to emigrate or were expelled from their places of residence in the course of the so-called small state of siege , which was temporarily imposed under the socialist laws on some of the SAP strongholds (e.g. Berlin , Hamburg , Leipzig or Frankfurt am Main ). The expellees lost their economic livelihoods and a significant number were mostly forced to emigrate to the USA.

The members of the party kept in contact with one another on an informal level in choral or support groups. The funerals of prominent party members regularly became the occasion for mass gatherings, which made the continued existence of the movement clear to the outside world. In 1879, 30,000 workers took part in August Geib's funeral in Hamburg. It was similar with the death of Wilhelm Bracke in Braunschweig . Since legal press work was no longer possible within the Reich, newspapers and magazines were published abroad and smuggled into Germany. On September 28, 1879, the Social Democrat's first sample number appeared in Zurich . While Marx and Engels declined to cooperate due to ideological differences with the party, among others Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein wrote for the paper, of which Georg von Vollmar became the editor in charge . In the years that followed, the sheet was brought to Germany in ever increasing editions and in the end some of it was even printed in the Reich itself. In the mid-1880s, around 12,000 copies of each issue were sold. The organization was led by the so-called " Red Field Post " of Joseph Belli and Julius Motteler . A less rigorous attitude in southern Germany enabled the publication of the theoretical journal Die Neue Zeit in Stuttgart from 1883 . Karl Kautsky became the publisher. Since 1884 the Berliner Volksblatt appeared in Berlin with the aim of trying to establish a new legal newspaper. Editors included Franz Mehring and Georg Ledebour . In the same year, Der Wahre Jacob , a social democratic satirical magazine, appeared again.

Overall, there were regional and temporal differences in the application of the law. In Prussia it was applied more strictly than in Baden. A milder practice can be observed in the years 1881/83, while from 1886 there was a marked tightening. The prosecution in particular increased during this period.

Elections and internal developments

Since party conferences were no longer possible in Germany, secret conferences were held abroad. For the first time since the Socialist Act was passed, such a meeting took place in August 1880 at Wyden Castle in the canton of Zurich . Aside from organizational issues, Congress turned against anarchist tendencies in parts of the party. The two best-known representatives of these tendencies - Johann Most and Wilhelm Hasselmann - were officially excluded from the SAP. In addition, the meeting decided to delete the word “legal” from the party program, as it was now pointless. The party is now striving by all means to achieve its goals. A similar congress was held in Copenhagen in 1883 .

In the Reichstag elections of 1881 , the party received 6.1% fewer votes than in the last election, but in view of the scarcely possible campaigning, this was a considerable success. With twelve MPs, the social democratic group was even stronger than before. However, August Bebel was defeated in several runoff elections and did not return to parliament until 1883. In the new legislative period , the introduction of social security should also serve to counteract the influence of the social democrats among the workers. This step was thus also an indirect recognition of the state that the social democracy could not be defeated with repression alone.

The Reichstag elections of 1884 were a great success for the party and made it clear that the social security legislation had hardly had any effect as a tool against social democracy. In these elections, nearly 550,000 voters voted for the SAP. This corresponded to 9.7% of the votes. Compared to the last election, this meant a gain of 76%. This had also contributed to the fact that the party had significantly better opportunities to advertise their cause. The Reichstag had determined in advance that the registration of electoral meetings did not fall under the provisions of the Socialist Act. However, in response to the success of SAP, the provisions of the law were subsequently implemented more strictly by the authorities.

The success of the Reichstag election meant that the faction grew to around two dozen MPs. With all satisfaction, the leadership group around Bebel, Engels and the young Bernstein, which was strictly Marxist-oriented at the latest with the Socialist Act, saw the danger that this would increase “parliamentary illusions”. In fact, there was a deep crisis in 1884/85 during the so-called steam subsidy dispute. The starting point was the question of whether it might make sense in times of economic crisis to tolerate these colonial-political subsidies with a view to jobs in the Reich. While this was rejected by a small "principled minority" around Bebel, who appealed to the members of the party, the majority of the parliamentary group spoke in favor of it in the interests of their voters. Between the faction majority and the leading personalities of the party there were ideological rifts that could hardly be bridged, which even a compromise proposal by Liebknecht could not really overcome. The newspaper Der Sozialdemokrat fully supported Bebel and the parliamentary group finally had to give up its attempt to control the paper. Although the newspaper promised to report on parliamentary work in future without polemics, Bebel's group ultimately prevailed. It is noteworthy that Liebknecht, who had been rather critical of parliamentarism in the past , played a balancing role in the parliamentary group during this time and also took his mandate extremely seriously.

A spectacular climax of the anti-social democratic measures was the so-called "secret society trial" which took place between July 26th and August 4th 1886 before the regional court of Freiberg in Saxony. Leading party members were accused of having been involved in a secret association. The prosecution viewed the Wyden and Copenhagen congresses as such. Ignaz Auer, August Bebel, Karl Frohme , Carl Ulrich , Louis Viereck and Georg von Vollmar were each sentenced to nine months and a number of other defendants to six months in prison. This process is followed by a whole series of further proceedings against participants in the two congresses. In Frankfurt alone, 35 defendants were sentenced to up to one year in prison. In Magdeburg there were 51 convicts in 1887.

In the Reichstag election of 1887 , the Social Democrats were able to gain further gains despite police reprisals and achieve 10.1% of the vote. However, they lost in various runoff elections against candidates from the German Liberal Party, so that the new parliamentary group was significantly smaller than the previous one.

In October 1887 another social democratic party congress took place in St. Gallen. This confirmed the previous attitude of the party to parliamentary activity, which was viewed primarily from the point of view of agitation. In addition, anarchism was again sharply criticized. At the same time it was decided that in future no more election agreements will take place with any bourgeois party, for example in runoff elections. A commission was set up to revise the party program. It was only at this congress that Bebel was able to fully enforce his undisputed leadership role in the party and parliamentary group, which he was to maintain until his death.

Towards the end of the 1880s, approval of the Socialist Law began to wane in the Reichstag. Although the majority approved the extension for another two years in 1888, they rejected all the tightening demands demanded by the government. Under pressure from the German government, Switzerland expelled the editors of the Social Democrat , and the paper has been published in London ever since .

At the international level there have long been efforts to found a new international. However, the different currents and directions of the labor movement could not agree. Therefore, from July 14th to 20th, 1889, two international workers' congresses with the same agenda took place in Paris . The German group consisting of 82 delegates took part in the founding of the congress that led to the founding of the Second International . As a German section, the SAP was considered the most influential socialist party of its time in Europe, despite a ban in its own country .

Towards the end of 1889, the Reich government submitted a new draft for a tightening of the Socialist Law, which, among other things, would have given it unlimited validity. This proposal was rejected by the Reichstag on January 25, 1890 by a clear majority with 169 votes against 98.

In the Reichstag elections of 1890, the opposition made significant gains, while Conservatives and National Liberals suffered significant losses. The SAP got 1.4 million votes. That was about 600,000 more than in 1887. With a share of the vote of almost 20%, the party had become the party with the largest number of voters in Germany. However, as in all previous elections, it was hampered by the constituency division and received only 35 seats.

On October 1, 1890, the Socialist Law finally expired. A total of 155 periodical and 1200 non-periodical publications were banned during the period of validity. 900 expulsions were pronounced and 1,500 people were sentenced to a total of 1,000 years in prison.

First party congress after the end of the Socialist Law

The first party congress after the Socialist Act was repealed took place from October 12th to 18th, 1890 in Halle . 413 delegates and 17 foreign guests were present. On the agenda were: the organization of the party (speaker Ignaz Auer), the party's program (speaker Wilhelm Liebknecht), the party press (speakers Ignaz Auer and August Bebel), the party's position on strikes and boycotts (speakers Karl Grillenberger and Karl Dumpling ). For August Bebel, during the years of the Socialist Law, agitation in free elections and the activities of the Reichstag faction proved to be the most effective means of agitation and the party should continue to adhere to this tactic in the future. The party congress decided to rename the party the SPD and adopted a new party statute. The organization was built on the shop steward principle. As a rule, the local labor electoral association should form the local party organization. As at the beginning of the party's history, the party congress was appointed the highest body of the party. The board consisted of twelve people: two chairmen ( Paul Singer and Alwin Gerisch were elected ), two secretaries, a cashier and seven controllers. The seat of the party was now Berlin. The Berliner Volksblatt , which was to appear from January 1, 1891 under the title Vorwärts - Berliner Volkszeitung , was appointed the party organ . The executive committee was instructed to present a new party program by the next party congress. This was the Erfurt Program adopted in 1891 . The party congress also acknowledged strikes and boycotts as weapons of the working classes and, like before the Socialist Act, advocated the establishment of central unions. In addition, the party congress proclaimed May 1 to be the permanent holiday of the workers. The parliamentary group in the Reichstag was called upon to continue to ruthlessly represent the fundamental demands of social democracy towards the state and the bourgeois parties in parliament. At the same time, however, it was also in favor of striving for reforms on the basis of the existing society. During the party congress, an inner-party opposition emerged for the first time, which was later referred to as the "boys".

change

The Socialist Law left its mark on the party for a long time. Instead of scattering the supporters, it promoted the emergence of a social democratic milieu as a subculture that isolates itself from “bourgeois society”. The fact that the party, which was initially heavily influenced by craftsmen and petty bourgeoisie, became a class party based on industrial workers in the 1870s and 80s also contributed to this. Nor was it intended by the government that the reformist tendencies should be pushed into the background during the prohibition period, due to a lack of practical implementation options and Lassalle's ideas in favor of a now principled Marxist party line. Only a few non-Marxists like Ignaz Auer were able to stay in the inner circle of the party leadership. The belief in the revolutionary power of the historical process also played a role. In addition to the anti-Dühring of Friedrich Engels , August Bebel's book Die Frau und der Sozialismus was particularly important for the reception and popularization of Marxism . It says in it

“Our presentation shows that the realization of socialism is not a matter of arbitrary tearing down and bulging, but rather of becoming a natural history. All factors that play a role in the process of destruction on the one hand and in the process of becoming on the other hand are factors that work how they have to work. "

Overall, the persecution in the party led to a process of radicalization. Parliamentarism was dismissed as an illusion and the focus was on revolution. Of course, they trusted that the “great Kladderadatsch” - as Bebel liked to say - would come about by itself as a result of the contradictions of the capitalist system. The party could therefore write the revolution on its flags without having to develop revolutionary activities itself. The revolutionary verbal radicalism together with reforming practice determined the character of the party in the following decades and shaped the internal conflicts.

See also

literature

- Franz Osterroth / Dieter Schuster: Chronicle of the German Social Democracy. Vol. 1: Until the end of the First World War . Bonn, Berlin, 1975. p. 50 ff.

- Detlef Lehnert: Social democracy between protest movement and ruling party 1848-1983 . Frankfurt, 1983 ISBN 3-518-11248-1 .

- Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1866-1918. Vol II: Power state before democracy . Munich, 1998. ISBN 3-406-44038-X .

- Helga Grebing : History of the German labor movement . Munich, 1966.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ cit. after: Gothaer Programm 1875 , printed in: Wilhelm Mommsen. German party programs. From March to the present . Munich, 1952. p. 100.

- ↑ Lehnert, Social Democracy , p. 66

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 50

- ↑ Chronicle, pp. 51–55.

- ↑ Lehnert, Social Democracy, pp. 68 f., Chronicle, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ see Christof Rieber: The Socialist Law: The Criminalization of a Party (PDF; 774 kB), Nipperdey, German History 1866–1918, Vol. 2, p. 356.

- ↑ Chronicle, pp. 67–75.

- ^ Nipperdey, German History 1866-1918 , Vol. 2, p. 356.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 61 f., P. 65.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 62 f.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 67.

- ↑ Lehnert, Social Democracy , pp. 73 f.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 69.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 70.

- ↑ Lehnert, Social Democracy , p. 76.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 74 f.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 75

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 76

- ↑ cf. Willy Albrecht End of Illegality - The Expiry of the Socialist Law and German Social Democracy in 1890 (PDF; 604 kB)

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 78 f.

- ↑ cit. according to Lehnert, Sozialdemokratie , p. 71 f., p. 76 f.

- ^ Nipperdey, Deutsche Geschichte 1866-1918 , Vol. 2, pp. 357 f.