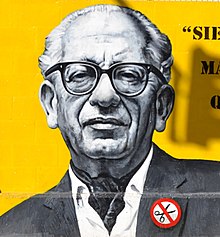

Max Aub

Max Aub , also Max Aub Mohrenwitz, (born June 2, 1903 in Paris , † July 22, 1972 in Mexico City ) was a Spanish writer of French origin with German ancestors. His life was marked by the European catastrophes of the 20th century: the Spanish Civil War , World War II and the Holocaust . His six-volume cycle of novels El laberinto mágico with around 3,000 pages is one of the most important depictions and literary analyzes of the Spanish Civil War.

life and work

Despite his origins in France, Aub is considered a Spanish writer because he wrote exclusively in Spanish . The original origin of the paternal family and their namesake is the small Franconian town of Aub , in whose Jewish community the ancestors of Max Aub can be traced back to the early 18th century. His father is the Munich sales representative Friedrich Aub and his mother Susana Mohrenwitz from Paris. Here Aub also spent a middle-class childhood and his school days at the Collège Rollin .

At the beginning of the First World War , Aub's father was on his way back from Spain when he was declared a persona non grata by the French state and he was refused entry. Max Aub then left Paris with his sister Magdalena and his mother and emigrated to Valencia . There he attended the schools Alliance Française and Escuela Moderna , in order to achieve the Abitur in 1920 at the state grammar school.

During his school days in Valencia, Aub a. a. with the later philosopher José Gaos and the writer Juan Chabás . But the later painter Genaro Lahuerta and the sociologist José Medina Echevarría have also been friends since school. Aub was recommended to study by his family and his teachers, but he decided - in order to become financially independent by his own admission - to become a sales representative like his father.

Even in his school days, Aub subscribed to several literary magazines (including Nouvelle Revue Française ) and began to try himself as a writer. Aub always used his business trips to come into contact with artists and writers. During these years he became friends with Jorge Guillén , Gerardo Diego , Federico García Lorca , Enrique Díez-Canedo and Luis Buñuel .

The latter encouraged Aub to play the first “experimental” plays, which of course were rarely or never performed (this has not changed until 2006). In 1923, Aub was in Saragossa , where he witnessed the coup of Miguel Primo de Rivera . Aub dealt with these experiences in his novel La calle de Valverde ('The Valverde Street'), in which the writers Vicente Blasco Ibáñez and Miguel de Unamuno also appear. Because of his poor eyesight, Aub was not used in any military service in his life.

On November 3, 1926, Aub married the Valencian Perpetua Barjau Martín . With her he had three daughters; María Luisa, Elena and Carmen. A year later he became a partner in his father's company. Always interested in politics, Aub joined the PSOE in 1929 . When the Second Republic was established in 1931 , Aub could also be heard as a political speaker at many events.

During this time he also made a name for himself in the theater. Together with Medina Echevarría and García Valdés , Aub traveled to the Soviet Union in 1933 to take part in a theater festival and possibly also to present his own plays. These are clearly influenced by Jacques Copeau , Max Reinhardt , Erwin Piscator and Bertolt Brecht . Aub was also quite open to the theories of Vsevolod Emiljewitsch Meyerhold , Konstantin Sergejewitsch Stanislawski and Alexander Tairow .

In 1934 and 1936, Aub directed the El Búho theater in Valencia . On various trips to Berlin , Madrid and Paris he came among others. a. in contact with André Malraux , Gustav Regulator and Ernest Hemingway . When the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936, Aub joined the Alianza de escritores antifascistas para la defensa de la cultura . In this context, he was instrumental in organizing an international writers' congress in 1936. There he met the Spanish ambassador in Paris, Luis Arquistaín , who spontaneously brought him to France as a cultural attaché at the Spanish embassy.

In this office - which he held from December 1936 to July 1937 - Aub commissioned Pablo Picasso for the picture Guernica (fee 150,000 francs) on behalf of the Spanish state . Aub presented this painting to the public at the 1937 World's Fair in the Spanish Pavilion.

Between January 1939 and April 1940, Aub lived with his family in France; During this time he tried to finish the film Sierra de Teruel, which he produced together with André Malraux, and began writing his first novels about the civil war at the same time.

1940: Denunciation and exile in Mexico

In March 1940 the Spanish embassy received an anonymous denunciation calling him a “German communist and a violent revolutionary”. The French ambassador of Spain, José Félix de Lequerica, adopted the denunciation and called on the French authorities to take immediate action against "this German (Jew) and notoriously dangerous communist". A little later, Aub was arrested and taken to the Roland Garros stadium and then to the Le Vernet camp. After his release, he worked in Marseille for the Emergency Rescue Committee , which despite all bureaucratic harassment tried to enable those persecuted by the Nazi regime to escape from Europe. For this reason, too, Aub was arrested again and again and was temporarily imprisoned. Friendship with Henri Matisse , André Malraux and André Gide was a support during the persecution . On November 27, 1941, Aub was deported to North Africa, to the labor camp in El Djelfa in the Algerian Sahara, because of his particular danger as an alleged communist on board the horse freighter Sidi-Aïcha . After seven months he was able to escape with the help of friends, but failed on the border with Morocco . The writer John Dos Passos got him an affidavit for his emigration to the USA . Because Aub missed his ship, the United States consular officers refused to renew the permit . For the next three months, Aub lived underground in Morocco and held out, among other things. a. hidden in the basement of a Jewish women's clinic in Casablanca . With the help of the Mexican consul in France, who u. a. had been made aware of Aub by Dos Passos, Aub was able to leave in September 1942. He arrived in Mexico City a month later . His wife and their daughters were not able to follow until 1946.

On Aub's literary reorientation after his emigration, Albrecht Buschmann writes: “In the first decade of his exile, the personality of the writer is formed, as he has become internationally known and famous since the 1950s. Aub, whose beginnings were shaped by experimental literary drafts, turns into a more realistic narrator who writes at the same time playful and politically engaged, witty and sharp, fantastic and documentary. In doing so, he processes subjects from his new homeland Mexico as well as Spanish topics, and here again and again the trauma of his life, the Spanish civil war. ”His character as an avant-garde, who primarily wanted to revolutionize theater, is always noticeable in his books it is in the language games and the fragmentary narrative style of the novels of the "Magical Labyrinth", be it in his little-known neo-avant-garde experiments such as the text card game "Juego de cartas" (1964), which renounces the binding as a book and its narrative fragments on the back of a deck of cards are printed: Even more radical than in Julio Cortázar's novel Rayuela (1963), the reader is forced to choose the sequence of his text himself.

In Mexico City , Aub taught film and theater studies at the Academy until 1951, and between 1943 and 1953 also worked as a screenwriter, director and translator. Among other things, he worked there with Luis Buñuel. In Mexico, he also ran a university radio station for several years. For a few years, Aub also sat on the jury of the Cannes Film Festival . Here in Mexico he became friends with Alfonso Reyes , Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes . From 1949 Aub published his magazine Sala de Espera ("Waiting Room"); In the 30 issues, Aub repeatedly expressed his hope of being able to return to Spain at some point.

1950: attempts to return

When Aub's father died in Valencia in 1951, the Franco regime forbade Aub's entry. Shortly before, Aub had wanted to meet in France with his parents, whom he had not seen since his escape. But the French state had also refused him entry and threatened to arrest his parents if he violated the law. In an open letter, Aub complained to President Vincent Auriol , but to no avail.

It was not until 1954 that Aub was allowed to meet his mother in southern France - subject to various conditions - with a tourist visa. Several trips to Europe followed. In 1958 he visited the Federal Republic of Germany. In 1961 he spoke on the occasion of the award of an honorary doctorate to his friend and colleague Dámaso Alonso .

When Aub's mother died in Valencia in September 1962, the Spanish authorities again refused him entry. At the turn of 1962/63, Aub was in New York to speak at an exhibition by the painter Jusep Torres Campalans - who, however, was a complete invention of Aub. Aub not only invented this figure for his novel of the same name; he also painted many pictures, which then found attention as Campalan's works. Albrecht Buschmann describes the details of this hussar coup. During this stay in the USA, Aub was also invited to give lectures by Harvard University and Yale University .

In 1966, Aub traveled to the Middle East on behalf of UNESCO and founded the Institute for Latin American Literature at the University of Jerusalem . He himself taught there from November 1966 to February 1967.

Between December 1967 and February 1968, Aub was in Havana , Cuba and was one of the most important speakers at a conference on the anti-fascist congress of 1937 as a contemporary witness. José Castellet and Jorge Semprún offered Aub a place on the jury of the Latin American cultural institute Casa de las Américas , which Aub was happy to accept. Since his daughter Elena lived married in Cuba, he stayed in the country regularly anyway.

In 1969, Aub visited his daughter María Luisa, who lived in London, and suffered a heart attack (probably due to the stress of traveling) that took him to the hospital for almost twelve weeks.

It was not until three years before his death, in August 1969, that Aub was granted a tourist visa by the Spanish government. With the help of Carlos Barral and Manuel Tuñón de Lara , he traveled all over the country until the end of November of the same year. Through Dámaso Alonso's mediation , Aub even managed to regain parts of his excellent private library; it had been confiscated during the war and made available to the Valencia University Library . However, he was not allowed to take with him works that the library did not have in any other edition.

Aub admitted indirectly in letters that the expectations with which he had set out on this trip had been disappointed: Franco's Spain was no longer his Spain. He died in Mexico City in 1972 at the age of 69.

Afterlife

Of the Spanish edition of works edited by Joan Oleza Simó (University of Valencia), 12 volumes were published between 2001 and 2012. It was initially planned to consist of 13 volumes, now 20 volumes are planned. In addition, Manuel Aznar Soler makes outstanding contributions to Aub's work as head of the exile literature research department at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and in his role as scientific director of the Max Aub Foundation. At the University of Valencia , especially since the preparations for the author's 100th birthday in 2003, numerous scientific activities have been initiated (conferences, exhibitions, doctorates, etc.).

A biography of Luis Bunuel, previously unpublished in German, was published in Spain in 2013 and was compiled from more than 5000 pages of notes from Aub.

In German, in addition to a selection of the short stories and the most important novels, a translation of Aub's six-volume main work on the Spanish Civil War, arranged by Albrecht Buschmann and Stefanie Gerhold, is available. Reviewer Sebastian Handke ( Die Tageszeitung ) highlights Aub's “distant, never committed tone” and “his cutting dialogues”, which miraculously turned his work into a “literally humanistic text”. Rainer Traub expresses himself similarly in the mirror . The reviewer Katharina Döbler admits in Die Zeit that the work is indeed labyrinthine, extremely difficult and “full of offenses against the morality of storytelling”. Aub draws a fictional chronicle along a barely perceptible, often disappearing red thread, which reaches from the eve of the war to those days on the pier in Alicante, where "the last of the republic were distributed to prisons, stadiums, temporary camps and mass graves" . Paul Ingendaay sees the cycle as “a fairly uneven work” of “radical modernity” and recognizes a “mixture of totality and unpredictability” in his composition. He concludes: “I know of no other work of this dimension that demands so much and seems to intend so little; which grabs the reader by the collar in a comparable way and then leaves them disoriented again; woos him in one place to give him a pat on the nose in another. "

Works (selection)

- Poemas cotidianos , poems, 1925

- Teatro incompleto , Dramas, 1931

- Las buenas intenciones , novel, 1954

- El laberinto mágico , six-volume novel cycle, 1943–68

- Jusep Torres Campalans , fictional artist biography, 1958

- La calle de Valverde , novel, 1961

- Enero en Cuba , Memories (fragment), 1969

- La gallina ciega , Memories (fragment), 1971

- Luis Buñuel, novela , biography. Cuadernos de vigia, Granada 2013

German editions

- The bitter dreams ("Campo Abierto"), Munich 1962

- The first angler's fault. Stories. Piper library, 177. Munich 1963

- The best of intentions (“Las buenas intenciones”), Frankfurt 1996

- The man made of straw , stories, Frankfurt 1997

- Jusep Torres Campalans . German. Eichborn Verlag 1997, ISBN 3-8218-0645-1 ; Book guild Gutenberg 1997, ISBN 3-7632-4734-3

- The magical labyrinth ("El laberinto mágico"), Frankfurt 1999 to 2003

- Nothing works anymore ("Campo cerrado"), 1999

- Theater of hope . ("Campo abierto"), 1999

- Bloody game ("Campo de sangre"), 2000

- The Hour of Betrayal ("Campo del Moro"), 2001

- At the end of the escape ("Campo francés"), 2002

- Bitter almonds ("Campo de los almendros"), 2003

- Max Aub, Francisco Ayala , Arturo Barea , Roberto Ruiz Ramon, Jose Sender, Manuel Andujar. Spanish storytellers: authors in exile - Narradores espanoles fuera de Espana. Edited and translated by Erna Brandenberger. Langewiesche-Brandt 1971; dtv , Munich 1973 a. ö. ISBN 3-423-09077-4 (bilingual)

- The Djelfa cemetery - El cementerio de Djelfa . In: Erna Brandenberger (Ed.): Fueron Testigos. They were witnesses. dtv, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-423-09303-X (bilingual)

literature

- Albrecht Buschmann: Max Aub and Spanish literature between avant-garde and exile . Mimesis series, 51st de Gruyter , Berlin 2012

- Albrecht Buschmann, Ottmar Ette (Ed.): Aub in Aub . Series: Potsdam Contributions to Cultural and Social History, 5th trafo, Berlin 2007

- Ignacio Soldevila: La obra narrativa de Max Aub . Gredos, Madrid 1973

- Ignacio Soldevila Durante (Ed.): Max Aub. Veinticinco años después , Editorial Complutense, Madrid 1999

- Lucinda W. Wright: Max Aub and tragedy. A study of "Cara y cruz" and "San Juan" . Dissertation, University of North Carolina , Chapel Hill, NC 1986

- Cecilio Alonso (ed.): Actas del Congreso Internacional "Max Aub y el laberinto español (Valencia y Segorbe, 13-17 de diciembre de 1993)" . Ayuntamiento, Valencia 1996

- Miguel Corella Lacasa: El artista y sus otros: Max Aub y la novela de artistas . Biblioteca Valenciana, Valencia 2003

- Ignacio Soldevila: El compromiso de la imaginación: Vida y obra de Max Aub . Biblioteca Valenciana, Valencia 2003

- María P. Sanz Álvarez: La narrativa breve de Max Aub , FUE, Madrid 2004

- Ottmar Ette (Ed.): Max Aub, André Malraux . Guerra civil, exilio y literatura , Vervuert, Frankfurt 2005

- Ottmar Ette (Ed.): Dossier: "Max Aub: Inéditos y Revelaciones" , special issue of the magazine Revista de Occidente, 265. Madrid June 2003, pp. 5–82

- James Valender (Ed.): Homenaje a Max Aub , Colegio de México, Mexico 2005

- José M. d. Quinto: Memoria de Max Aub , Fundación Max Aub, Segorbe 2005

- Javier Quiñones: Max Aub, novela (novel). Edhasa, Barcelona 2007

- Gérard Malgat: Max Aub y Francia o la esperanza traicionada . Fundación Max Aub (Segorbe) y Renacimiento, Seville 2007

- Max Aub - Ignacio Soldevila Durante. Epistolario: 1954-1972 . Edición estudio introductorio y notas de Javier Lluch Prats, Biblioteca Valenciana - Fundación Max Aub, Valencia 2007

- José Rodriguez Richart: Dos patrias en el corazón. Estudios sobre la literatura española del exilio , Madrid 2009

- Eric Lee Dickey: Los Campos de La Memoria. The concentration camp as a site of memory in the narrative of Max Aub. ProQuest, UMI Dissertation Publ. 2011, ISBN 124406923X (in English)

- Claudia Nickel: Spanish civil war refugees in camps in the south of France: rooms, texts, perspectives. (= Contributions to Romance Studies, Vol. 15). Scientific Book Society (WBG), Darmstadt 2012. ISBN 978-3-534-13621-6

- Max Aub: La narrativa apócrifa - Obras completas IX . Edición crítica y estudio de Dolores Fernández Martínez, Joan Oleza y Maria Rosell. Madrid: Iberoamericana / Frankfurt aM: Vervuert 2019. ISBN 9788491920151

Web links

- Max-Aub Foundation, Segorbe

- Literature by and about Max Aub in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Max Aub in the German Digital Library

- Literature by and about Max Aub in the catalog of the Ibero-American Institute of Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin

- Literature by and about Max Aub in the catalog of the library of the Instituto Cervantes in Germany

- Maxaubiana 2001. Ensayo bibliográfico. By Ignacio Soldevila Durante, Catedrático Emerito, Université Laval , Quebec. A complete primary and secondary bibliography up to 2001, all languages, all places of publication, as far as it was possible to record it

- Max Aub filmography in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ When the First World War broke out, people of German origin living in France were classified as dangerous. In 1915, France became the first state to make denaturalization, i.e. expatriation, of nationals possible (see stateless persons ).

- ↑ Gérard Malgat wrote the most important studies of Max Aub's time in France. The sources for Aub's denunciation can be found in Gérard Malgat: Holocausto . In: Juan María Calles (ed.): Max Aub en el laberinto del siglo XX . Segorbe, Valencia 2006, pp. 108-133.

- ↑ Albrecht Buschmann: The bull in the labyrinth. Max Aub in Spain and Mexico. ( Memento of October 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), 1997. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ↑ A detailed analysis of "Juego de cartas" can be found in Buschmann (2012: 151-181).

- ↑ CULTurMAG: Literature, Music & Positions, February 26, 2004, Max Aub: Jusep Torres Campalans - An exquisite picaresque piece by Karsten Herrmann, accessed on August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Albrecht Buschmann: The bull in the labyrinth. Max Aub in Spain and Mexico. ( Memento of October 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), 1997. Retrieved on March 20, 2012. More detailed than in this newspaper article in Buschmann (2012: 37-66).

- ↑ Der Stern: Buñuel biography by Max Aub published ( Memento of November 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) on November 5, 2013.

- ↑ Paul Ingendaay : Black Book of Powerlessness. About the afterlife of the «Magic Labyrinth». In: Albrecht Buschmann (ed.): Pictures of life in the window of the century. Portraits, conversations, appraisals. With drawings by Jusep Torres Campalans. die horen # 210, vol. 48, issue 2, Wirtschaftsverlag Neue Wissenschaft, 2003, pp. 19–26 (special issue Aub).

- ↑ therein «Der Klumpfuss», pp. 5–30, translated by Gustav Siebenmann. Other stories besides the eponymous one: Fire in the valley ; The silence , translated by Gustav Siebenmann and Hildegard Baumgart.

- ↑ Treated u. a. Aub's friendship with the playwright Alejandro Casona . Letters from the two of them are reproduced.

- ↑ At the end of the civil war, many Spaniards, almost half a million, fled to France, where they were placed in temporary camps. In this situation, literature played a major role. Nickel presents literary texts by Spanish authors such as Aub or Agustí Bartra and places them in the context of so-called camp literature. Authors' contributions on the social and ethical aspects associated with flight, internment and exile are worked out. The texts record the reaction of those affected to the exclusion, they highlight repressed issues.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Aub, Max |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 2, 1903 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 22, 1972 |

| Place of death | Mexico city |