work sets you free

The slogan or phrase Arbeit macht frei became known through its use as a gate label at the National Socialist concentration camps . By perverting its original meaning, it is now understood as a cynical slogan that mocked the victims and used to cover up the inhumane treatment in the concentration camps, where work served the submission , exploitation , degradation and murder of people.

prehistory

Heinrich Beta used the formulation in 1845 in the text Money and Spirit : “It is not faith that makes you happy, not belief in selfish priestly and noble purposes, but work makes you happy, because work makes you free. That is not Protestant or Catholic, or German or Christian Catholic, not liberal or servile, that is the general human law and the basic condition of all life and striving, all happiness and bliss. ”(Emphasis in the original).

It can also be found in 1849 in the literary journal New Repertory for Theological Literature and Church Statistics , where in a review of the German translation of the text L'Europe en 1848 by Jean-Joseph Gaume it is argued: “The Gospel and, on its original truth going back, the Reformation want to educate free people and only work creates free, is therefore something sacred according to the terms of the reformers. "

Work makes free is also the title of a story by German national author Lorenz Diefenbach published in 1873 (preprinted in 1872 in the Wiener Zeitung Die Presse ). In 1922 the German School Association Vienna printed contribution stamps with the inscription "Arbeit macht frei" together with the swastika.

How an affinity for this saying came about in National Socialist circles has not yet been conclusively clarified. What is certain is that there is a reference to the duty to work in the warehouse regulations. “Work” almost exclusively meant hard physical work.

Use in the concentration camps

In some Nazi concentration camps , the gate sign was a cynical paraphrase for the alleged educational purpose of the camps, the actual purpose of which was often destruction through labor . The historian Harold Marcuse , the use as KZ-motto on Theodor Eicke , the first SS - commander of the Dachau concentration camp, back.

Martin Broszat assumed that Rudolf Höß , who was responsible for the affixing, "meant it seriously to a certain extent in his limited way of thinking and feeling". “From the modern myth of the working spirit, which was ultimately considered to be specifically German, arose one of the extermination strategies of the genocide .” In addition to the gate inscription , a slogan from Heinrich Himmler was clearly displayed in some concentration camps - for example on the farm building of the Dachau concentration camp as well as in Sachsenhausen and Neuengamme : “There is a way to freedom. His milestones are: obedience, hard work, honesty, order, cleanliness, sobriety, truthfulness, self-sacrifice and love for the fatherland! ".

Auschwitz

At the gate of the main camp Auschwitz there is the writing “Arbeit macht frei” with an upside down letter B. Former Auschwitz prisoners report that it was a secret protest by their fellow prisoner Jan Liwacz , who as an art fitter did several commissioned works for the SS had to execute, including the lettering in 1940.

theft

The original lettering was stolen in the early morning hours of December 18, 2009. That same morning it was replaced by a copy that had already been made for use during previous restoration work. To clear up the theft, the Polish police launched a large-scale manhunt and tightened border controls. Three days after the theft, the lettering was found in a forest hiding place in northern Poland. The inscription had been broken down into three parts of one word each. Five men between the ages of 20 and 39 were arrested. The lettering was restored in the memorial workshop. It was announced that it will not return to its old location, but will be shown in a closed room of the museum in the future.

In December 2010, the Swede Anders Högström , who is seen as the mastermind behind the theft, was sentenced to two years and eight months in prison in Poland . Two Polish accomplices were imprisoned for more than two years. Three other Polish accomplices were previously sentenced to prison terms of between one and a half and two and a half years. Högström was supposed to serve his sentence in Sweden. According to his own statements, he wanted to resell the lettering in Sweden.

Auschwitz-Monowitz

It is unclear whether there was a “work makes you free” sign in Auschwitz-Monowitz . This is what Primo Levi and the then British soldier Denis Avey claim in his book The Man Who Broke into the Concentration Camp . The historian Piotr Setkiewicz from the Auschwitz Museum doubts that there was such a sign at Monowitz.

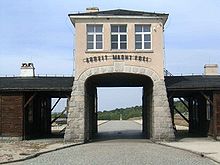

Dachau

In the Dachau concentration camp , the slogan “Work makes you free” was embedded in a wrought-iron gate that closed the passage to the newly built entrance building to the prisoner camp in 1936. The Nuremberg concentration camp inmate Karl Röder reports that he had to forge the motto in the security workshop of the concentration camp. In the Dachau concentration camp, Jura Soyfer wrote the well-known Dachau song , in whose refrain the saying “work makes you free” is taken up.

theft

On the night of November 2, 2014, the historic door at Jourhaus , which formed the main entrance to the prisoners' area of the former Dachau concentration camp and is now the entrance to the memorial, was stolen by unknown perpetrators. The door contains the words “Arbeit macht frei”. A good two years later, on December 2, 2016, the door was found again in the city of Bergen in western Norway, according to Norwegian police . The police arrested her after an anonymous tip. How it got to Norway should be clarified across borders. The door returned to Dachau on February 22, 2017. In future, it will be on display in the museum's permanent exhibition in an alarm-secured and air-conditioned display case. The replica made in April 2015 on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp remains at the entrance gate .

Beech forest

The only concentration camp with a different gate heading was the Buchenwald concentration camp with the slogan “ To each his own ”. This quote goes back to the Roman poet and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero : Justitia suum cuique distribuit (“Justice gives everyone his own”). Abbreviated in "suum cuique" it became a motto of the Prussian kings. As an inscription it adorned the High Order of the Black Eagle , founded by Frederick the Great in 1701 . On the wall frieze above the iron gate of Buchenwald it also read: Right or wrong my fatherland . The volume of poetry by the former Buchenwald prisoner Karl Schnog , published in 1947, bears the title Everyone is His .

Use in the present

Its use, combined with a lack of knowledge of the history of this slogan, regularly leads to a scandal . A well-known example is the moderator Juliane Ziegler .

During the Bundestag election campaign in 2005 , the then deputy SPD chairman Ludwig Stiegler stated that the CDU's election slogan “Social is what work creates” reminds him of “Work makes you free”. He later apologized for the comparison.

In 2010, a corruption of the expression by the Aeroclub in Treviso caused a stir, which protested against the planned closure of the local airport with an inscription based on the Auschwitz sign, “Fly makes you free”.

In 2012, a freelance presenter and an assistant of the local radio station Gong 96.3 were dismissed because the presenter addressed the listeners who had to work on the last Saturday in July in a program with the words Arbeit macht frei . Investigations into incitement were therefore initiated at the Munich public prosecutor's office .

In July 2017, the Serbian news magazine Nedeljne Informativne Novine used the sentence on the front page.

literature

- Wolfgang Brückner : "Work makes you free". Origin and background of the concentration camp motto (= Otto von Freising lectures of the Catholic University of Eichstätt. 13). Leske + Budrich, Opladen 1988, ISBN 3-8100-2207-1 .

- Wolfgang Brückner: Memorial culture as a scientific problem. Concentration camp emblems in museum didactics. In: Gunther Hirschfelder, Dorothea Schell, Adelheid Schrutka-Rechtenstamm (Ed.): Cultures - Languages - Transitions. Festschrift for Heinrich Leonhard Cox on his 65th birthday. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-412-11999-7 , pp. 525-565.

- Eric Joseph Epstein, Philip Rosen: Dictionary of the Holocaust. Biography, Geography, and Terminology. Greenwood Press, Westport CT et al. a. 1997, ISBN 0-313-30355-X .

- Dirk Riedel: “Work sets you free.” Motto and metaphors from the world of the concentration camp. In: Wolfgang Benz , Barbara Distel (Hrsg.): Reality - Metaphor - Symbol. Confrontation with the concentration camp ( Dachauer Hefte. 22). Verlag Dachauer Hefte , Dachau 2006, ISBN 3-9808587-7-4 .

- Friedrich-Ebert-Gymnasium Mühlheim (ed.): Work makes you free! Schoolchildren search in Auschwitz. Student project 2012: Remember what happened to you in Auschwitz of the Friedrich-Ebert-Gymnasium Mühlheim. Prager-Haus, Apolda 2012, ISBN 978-3-935275-25-5 (part of the Anne Frank Shoah Library ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ "Work makes you free": Origin and background of the concentration camp motto. Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-322-92320-2 ( google.com [accessed on May 5, 2016]).

- ^ Hermann Kaienburg : Concentration Camps and German Economy 1939–1945 . Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-322-97342-9 ( google.com [accessed on May 15, 2016]).

- ^ Heinrich Bettziech (Beta) : Money and Spirit. Attempt to sift through and redeem the working people's power. AW Hayn, Berlin 1845, p. 57 .

- ↑ Th. Bruns, C. Häfner (Ed.): Review of Europe in 1848 by J. Gaume, New Repertory for Theological Literature and Church Statistics 19, 1849, p. 38 .

- ↑ Lorenz Diefenbach : Arbeit macht frei , Die Presse 225–263, August 17 to September 24, 1872 ( at ÖNB / ANNO ); J. Kühtmann's Buchhandlung, Bremen 1873 ( at the GDZ ).

- ^ Hermann Kaienburg: Concentration Camps and German Economy 1939–1945 . Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-322-97342-9 ( google.com [accessed on May 15, 2016]).

- ↑ Harold Marcuse: Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001 . Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-521-55204-2 ( google.com [accessed May 15, 2016]).

- ↑ Review: Non-fiction book: Murder as work . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . March 17, 1999, ISSN 0174-4909 ( faz.net [accessed May 15, 2016]).

- ↑ “Work makes you free”: Thieves steal lettering from Auschwitz gate. Spiegel Online from December 18, 2009.

- ↑ Stolen Auschwitz lettering seized ( Memento from December 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Tim Allman: Infamous Auschwitz 'Arbeit macht frei' sign restored. In: BBC News , May 19, 2011.

- ↑ "Work makes you free" theft: masterminds sentenced to prison. In: Spiegel Online , December 30, 2010.

- ^ Primo Levi and the language of witness . 1993. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved on November 17, 2011: "Levi remembers vividly the slogan 'Arbeit Macht Frei' (work gives freedom) illuminated above the front gate through which he entered the Monowitz camp at Auschwitz."

- ↑ Secretly in Auschwitz: The Outrageous Story of a British Prisoner of War ( Memento of December 30, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), Das Erste

- ↑ Dirk Riedel : “Work makes you free”. Mission statements and metaphors from the world of the concentration camp. In: Dachauer Hefte, 22 (2006), p. 11 f. on-line

- ↑ Thieves steal the historic main entrance door of the Dachau concentration camp. In: Zeit Online , November 2, 2014.

- ↑ Porten ble stålet fra en Konsentrasjonsleir - nå har den dukket opp i Ytre Arna. In: Bygdanytt , December 2, 2016.

- ↑ Gate of the concentration camp memorial apparently found in Norway. In: Spiegel Online , December 2, 2016.

- ↑ The stolen gate is back in Dachau. In: Spiegel Online , February 22, 2017, accessed on the same day.

- ↑ Found stolen concentration camp gate from Dachau in Norway. Süddeutsche Zeitung , December 2, 2016.

- ^ National Socialism - Work Makes You Free / Everyone Has His Own GRA , 2015.

- ^ Andreas Laux: Television: Nazi scandal on ProSieben. In: focus.de , January 30, 2008.

- ↑ Susanne Ruhland / AP: Bundestag election: kick-off for the final. In: stern.de. July 22, 2005, accessed April 11, 2019 .

- ^ Trouble about the airport logo in the style of a concentration camp ( memento from November 24, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), report by Swiss television from November 21, 2010.

- ↑ Moderator dismissed after a Nazi statement. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , August 9, 2012.

- ↑ www.3sat.de