Albert Ganzenmüller

Albert Ganzenmüller (born February 25, 1905 in Passau ; † March 20, 1996 in Munich ) was a German graduate engineer and Reichsbahn official, most recently as State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of Transport (RVM) and Deputy Director General of the Deutsche Reichsbahn . He is considered the prototype of a technocratic National Socialist .

As a student, he took part in the 1923 Hitler coup . After 1933, Ganzenmüller was one of the few old fighters at the Deutsche Reichsbahn who was also seen as professionally competent. The mechanical engineer with a doctorate quickly climbed the career ladder at the Reichsbahn. In 1942 he became State Secretary in the RVM at the request of Albert Speer . In this position Ganzenmüller was responsible, among other things, for the deportation of Jews from Germany and the occupied states as well as other victims of the National Socialist genocide with the Reichsbahn to the extermination camps . During his tenure as State Secretary, more than a million people were deported to Auschwitz . Ganzenmüller took care of the smooth transport to the camps personally and in coordination with the SS . In 1945 he fled over the rat lines to Argentina , where he advised the nationalized railways. In 1955 he returned to Germany.

Ganzenmüller is the only Reichsbahner against whom criminal proceedings for aiding and abetting murder were opened due to his involvement in the National Socialist extermination policy. A verdict was never reached because Ganzenmüller was considered incapable of standing from 1973 until his death .

Life

Training and entry at the Reichsbahn

Ganzenmüller was the son of a farmer; his family came from the Donau-Ries . In 1924 Ganzenmüller passed his high school diploma at a secondary school in Munich and in the same year began studying mechanical engineering at the Technical University of Munich , which he graduated in 1928 as a graduate engineer. Also in 1924 he became a member of the Corps Rheno-Palatia .

In 1928 Ganzenmüller became a trainee trainee at the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft in the Reichsbahndirektion in Munich . After the state examination in 1931 he was taken on as a Reichsbahnbau assessor for further training in the Reichsbahndirektion Nürnberg . From March 24, 1932, he was Reichsbahnbaumeister and from April 1, 1934, as planned, as Reichsbahnrat , from October 1, 1938 as Reichsbahnoberrat (comparable to the official title of Oberregierungsrat ) and from October 1, 1940 as department president (comparable to a government vice-president ) employed by the Deutsche Reichsbahn . He was used in Breslau , Munich, Nuremberg and Berlin . In Munich, among other things, he worked for Wolfgang Bäseler's research institute at the Reichsbahn Central Office . He received his doctorate in 1934 at the Technical University of Wroclaw under Georg Lotter with a thesis on road-rail vehicles .

Career in National Socialism

Already during his school days Ganzenmüller joined the paramilitary United Patriotic Associations of Germany (VVVD) in 1922 , where he received pre-military training. During the Hitler putsch on 8/9 November 1923 he belonged to the "Shock Troop South of the Kampfbund Reichskriegsflagge ", which occupied the military district command in Munich. For his participation in the putsch in 1933 he was awarded the so-called blood order donated by Adolf Hitler . Ganzenmüller was awarded number 141 .

On April 1, 1931, he joined the NSDAP (membership number 483.916) and in April 1932 the SA (Gausturm Munich-Upper Bavaria). In 1940 Ganzenmüller had reached the rank of Standartenführer in the staff of the Supreme SA leadership . As an employee of the technology office in the NSDAP- Gau Franken and the main office for technology of the NSDAP in Munich, he “put his technical skills in the service of the movement”, as a résumé published in 1942 records.

Ganzenmüller in 1934 after his graduation to Reichsbahnrat transported and Reichsbahn Central Office put in Munich. A year later he was head of the department for electric locomotives at RAW Munich . In this function, he presented a new electric railcar to Adolf Hitler on December 8, 1935, on the occasion of the anniversary parade for the 100th birthday of the German railways in Nuremberg . From January 1937 to May 1939 Ganzenmüller worked as an " unskilled worker " for electric train operations in the Reich Ministry of Transport . In 1938 he was appointed to the senior government council, then in 1939, after a brief position on the board of a machine office, department head for electrical engineering at the Reichsbahn central office in Munich.

Ganzenmüller had meanwhile married and had two children. In 1940 his marriage failed and he volunteered for the special task of restarting electric train operations in occupied France for the Wehrmacht traffic directorate in Paris after the campaign in the west . He then took on again various higher posts at the Reichsbahn; From May 1941 he headed the electrical operations management in Innsbruck under the title "Vice President" , which was responsible for all electrically operated lines of the Reichsbahn in the four existing sub-networks in Baden , Central Germany , Silesia as well as Bavaria and the East Mark .

In October 1941 he was transferred to the "Main Railway Directorate East" in Poltava at his own request . There he removed traffic congestion in a short time and took care of the re-gauging of the tracks and vehicles of Soviet railways, which was essential for the war effort . This not only caught the attention of the Reichsbahn General Director and Minister of Transport Julius Dorpmüller , who visited Ganzenmüller in Poltava in February 1942. Even Albert Speer , the new defense minister, who is now looking for solutions that has occurred in the winter of 1941-42 transportation crisis in the east, fell to the force as energetic and competent Ganzenmüller.

Promotion to State Secretary

Since Speer had become Reich Minister for Armaments and Ammunition on February 8, 1942 , he had criticized what he saw as the insufficient work of the Reichsbahn and initially promoted the replacement of the then 73-year-old Transport Minister Dorpmüller. Hitler, who needed Dorpmüller as a figurehead and “loyal Eckehard” of traffic, stuck to him. Speer therefore focused his criticism on State Secretary Wilhelm Kleinmann , who, at 65, was also significantly older than Speer's preferred young technocrats and engineers. Dorpmüller initially refused to dismiss Kleinmann, whereupon Speer approached Hitler again. On May 13th or 18th, 1942 Speer recommended Ganzenmüller with reference to his achievements in the Ukraine. Ganzenmüller fully complied with Speer's ideas, for example, in that he refused to sign documents that were longer than four pages. Hitler agreed to Speer's proposal after Transport Minister Dorpmüller had told Speer that the Reichsbahn could no longer take responsibility for the most urgent transports due to a lack of locomotives and wagons. Hitler, who had already threatened Kleinmann very clearly with the Gestapo in February , appointed Ganzenmüller on May 25, 1942 at Speer's suggestion as Kleinmann's successor as State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Transport and Deputy Director General of the Reichsbahn. As Kleinmann's successor, he also became a representative of the Reich Ministry of Transport at the General Council for the four-year plan . At the time of his inauguration, Hitler explicitly set Ganzenmüller the task of solving the transport crisis that had occurred “with the greatest recklessness”. Kleinmann was deported to Mitropa as a director . Ganzenmüller left the service villa to his predecessor and contented himself with a rented apartment.

The new state secretary, only 37 years old, was not only recognized as a blood medalist in the party, he was also valued as a competent specialist within the Reichsbahn. With a height of 1.86 m, blond hair and distinctive facial features marked by smudges , he also outwardly corresponded to the ideal image of the "Nordic race" according to the racial ideology of National Socialism. Ganzenmüller initially tried to motivate the railroad workers by appeals to be more motivated. As one of his first activities in the new office, he initiated the propaganda campaign “ Wheels must roll for victory! ". Other measures initiated by Ganzenmüller to solve the transport crisis were the rental of foreign freight wagons , the dissolution of wagon reserves, the approval of an overload of wagons by up to two tons as well as greater efforts to reduce the number of damaged wagons and to speed up loading and unloading. The operation of dining cars was discontinued, and tightened registration cards were introduced for sleeping cars . During the summer of 1942, various senior senior officials of the RVM, such as Paul Treibe , head of department E I (traffic and tariff), and Max Leibbrand , head of department E II (operations), as well as various presidents of the Reichsbahn retired. They were replaced by younger men, such as Fritz Schelp as the new head of Department E I and Hans Geitmann , who took over the important Reich Railway Directorate in Opole . Like Ganzenmüller himself, these men were usually close to the party and at the same time were regarded as technically competent. Ganzenmüller also increasingly emerged through publications in Reichsbahn publications. In September 1942 he characterized the achievements of the Reichsbahn as “a small maneuver”, which, however, would be followed by “the greatest transport battle of all time”. On January 1, 1945, he called on the railway workers to hold out. 1945 would be “a year of the German attack” and it was now “even more important” to drive.

Ganzenmüller continued to strive for a better integration of the Eastern Railway in occupied Poland. First, by speaking to Hitler, he achieved that the Eastern Railway was organized analogously to the Reichsbahn. On October 26, 1942, Ganzenmüller appeared at the head of the Reich Chancellery , Hans Heinrich Lammers . Lammers asked Hitler personally about his ideas about the organizational and financial integration of the Eastern Railway. Ultimately, Ganzenmüller and Dorpmüller could not prevail against Governor General Hans Frank ; the Ostbahn remained outside the Reichsbahn and a special fund of the Generalgouvernement .

During his tenure, Ganzenmüller made numerous business trips, including six to the occupied territories in the east, as far as the Caucasus and near Stalingrad . At a meeting of the Reich and Gauleiter in Posen on February 5 and 6, 1943 , two days after the surrender of German troops at the Battle of Stalingrad , Ganzenmüller, as a representative of the Reich Ministry of Transport, gave a lecture on the problems to be solved in the transport sector. On February 7th, the participants drove together to the “ Wolfsschanze ”, where they were received by Hitler.

Hitler thought so much of Ganzenmüller's work that in May 1943 he considered him as a possible successor to Dorpmüller. On September 19, 1943, he personally awarded him and Dorpmüller the " Knight's Cross for War Merit Cross with Swords". Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels also praised Ganzenmüller's performance as "at certain times directly decisive for the war". Ganzenmüller had already been the holder of the Golden Party Badge of the NSDAP since January 30, 1943 . On the other hand, Ganzenmüller avoided too closely following the SS . He apparently eluded Himmler's attempts to bind him more closely to himself by awarding him an SS honorary rank .

Although Ganzenmüller had been promoted as a technocrat and party member by Speer, he defended his own positions in the polycratic competence wrangle typical of the Nazi regime and tried to protect the interests of the Reichsbahn against other authorities and ministries. In April 1943, he refused a flat-rate billing of costs by the Wehrmacht with the Reichsbahn. At the end of 1944, the differences between him and his original mentor Speer became clear when, on December 5, he fought off an attempt by Speer to appoint authorized transport agents from his ministry to bring the Reichsbahn into his area of responsibility.

In other cases Ganzenmüller and Speer worked together against other Nazi institutions and people. In September 1944 both tried to oppose an instruction from Goebbels, who had also been a general agent for the total war effort since the summer of 1944 . Goebbels had requested that uk- employed Reichsbahner for the Wehrmacht, d. H. to release the front insert. Like Speer, Ganzenmüller had argued that this would jeopardize the functioning of his institution. With Speer's support, Ganzenmüller was ultimately able to prevail, similarly to Martin Bormann , who wanted to assign Reichsbahner to the Volkssturm .

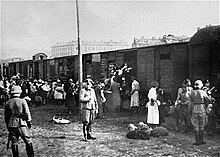

Participation in deportations and forced labor

As State Secretary and Deputy General Director of the Deutsche Reichsbahn, Ganzenmüller has been involved in organizing the deportation trains since he took office. He was involved in the deportation of older German Jews to the Theresienstadt ghetto and ensured that the transports to the Aktion Reinhardt mass extermination camps ran smoothly . H. the deportation of over two million Jews and around 50,000 Roma who were deported from the five districts of the Generalgouvernement ( Warsaw , Lublin , Radom , Cracow and Galicia ) to the three extermination camps Belzec , Sobibor and Treblinka between July 1942 and October 1943 .

Since the end of the attack on Poland in September 1939, the Eastern Railway in the Generalgouvernement had been entrusted with "resettlement transports", which later included the deportations of Jews to ghettos and camps. When, in the early summer of 1942, the Higher SS and Police Leader in the General Government, Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger , demanded the provision of special trains for planned major actions against the Jewish population, the President of the General Management of the Eastern Railway (Gedob) , Adolf Gerteis , stated because of the high To be able to provide only a few trains to the Wehrmacht's means of transport . On one of his first business trips to Krakow on June 26, 1942, Ganzenmüller discussed this with Josef Bühler , Deputy Governor General, and Adolf Gerteis, among others . In addition, in July 1942, construction work was carried out on the railway line that led towards the Sobibor extermination camp . At the same time, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler urged that the Jews in the Generalgouvernement be deported to the extermination camps as quickly as possible , and had obviously spoken to Hitler about this on July 16, 1942 at the Fuehrer's headquarters . On the same day, his personal adjutant Karl Wolff phoned the new State Secretary Ganzenmüller from there. The sociable Wolff had already maintained connections to Ganzenmüller's predecessor Kleinmann. Wolff then asked Ganzenmüller to use his influence on the Gedob to provide more transport space for the SS .

Ganzenmüller informed Wolff in a letter on July 28, 1942 under his own letterhead and with his own signature:

“Since July 22, there has been a daily train with 5,000 Jews from Warsaw via Malkinia to Treblinka , and a train with 5,000 Jews from Przemysl to Belzec twice a week . Gedob is in constant touch with the Krakow security service . He agrees that the transports from Warsaw via Lublin to Sobibor (near Lublin) will be suspended as long as the reconstruction work on this route makes these transports impossible (around October 1942) "

Karl Wolff thanked him in a personal letter on August 13, 1942:

"[...] I was particularly pleased to learn that a train with 5,000 members of the chosen people has been going to Treblinka every day for 14 days and that we are in a position to manage this population movement all in one accelerated pace. "

In this obscuring diction, Wolff confirmed that the deportation and murder of the residents of the Warsaw ghetto had now begun.

On September 2, 1942, Fritz Kranefuß , secretary of the Friends of the Reichsführer SS , called on Himmler's representative in a kind of "inaugural visit" to Ganzenmüller to negotiate details such as the transport costs for the deportations. Ganzenmüller, like his predecessor, who was a member of the Freundeskreis, assured that it would continue to run smoothly. The SS still wanted Kleinmann to be a point of contact.

After several attempts, Ganzenmüller received his first meeting with Himmler on December 3, 1942. However, more detailed information on the topics of conversation is missing, Gottwaldt and Schulle suspect that the Reichsführer SS wanted to ensure that the Christmas ban on special trains did not affect the deportation trains. On January 23, 1943, Heinrich Himmler wrote to Ganzenmüller again. Regardless of the tense situation - the defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad was looming - Himmler demanded “more transport trains” because he wanted “to get things done quickly”. He justified this with the fact that "gang helpers and gang suspects" had to be removed in order to pacify the Generalgouvernement and the Russian territories. This also includes “primarily the removal of the Jews” and “the removal of the Jews from the West”. In fact, the agreed special trains were resumed on January 20, 1943.

As in the deportations, Ganzenmüller was also involved in the use of forced labor . In 1944 he assigned the Reichsbahn department president Joseph Merkel as "Reichsbahn representative for the central building project". In May 1944, Mittelwerk GmbH again commissioned the Reichsbahn to plan and build a 22 km long new rail route, the Helmetalbahn , under Merkel's direction. Mittelwerk GmbH produced a. a. the V2 rocket. Prisoners from the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp , a temporary satellite camp of the Buchenwald concentration camp, were used as labor . Countless concentration camp prisoners died during construction and production.

The Reichsbahn itself also employed numerous forced laborers under Ganzenmüller's aegis, initially mainly for physically demanding work in track construction and loading goods. Over the years, forced laborers were also used as locomotive heaters and even train drivers .

After the end of the war

The US Transport Division proposed Ganzenmüller, whose personal involvement in the Holocaust was hardly known by the Allies at the time, in 1945 because of his undisputed qualification as a railway specialist, initially as head of the Reichsbahn in the American zone of occupation . Together with his boss, the Reich Minister of Transport and General Director of the Deutsche Reichsbahn, Julius Dorpmüller , Ganzenmüller was brought to Le Chesnay near Paris for the first talks and questioning shortly after the end of the war on May 25, 1945 . The United States Department of State protested this vigorously; Ganzenmüller did not consider it acceptable because of his political attitude. On May 30, 1945 Ganzenmüller was questioned by the American Strategic Bombing Survey about the effects of the bombing raids on rail traffic and confirmed the effectiveness of the attacks. Shortly after Dorpmüller's return to Germany on June 13, 1945, Ganzenmüller was also brought back to Germany.

Robert Kempner , US deputy chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials , looked for Dorpmüller as well as his State Secretary Ganzenmüller, but could not find either of them at first. Dorpmüller died in July 1945, and Ganzenmüller was wanted as " Theodor Ganzenmüller " due to a mix-up by the Allied secret services with a professor emeritus from Munich . No representative of the Reichsbahn was therefore charged in Nuremberg; for this reason, too, their role in the persecution of the Jews remained unknown. Speer also included this false first name in his memoirs.

Since his return from Paris Ganzenmüller had been in the American Civilian Internment Camp No. 6 in Moosburg an der Isar , but was considered lost by Kempner. On the night of December 8th to 9th, 1945 he managed to escape. He came to Argentina via the rat lines .

During his absence, Ganzenmüller was denazified on December 23, 1949 by the Main Chamber of Munich as a group II suspect , after several judicial proceedings had previously been delayed by family members. An appeal was dismissed on March 11, 1950. After an amnesty in March 1952, the proceedings were finally abandoned. Ganzenmüller married a second time in Argentina in 1952. He then tried unsuccessfully to sue for his pension as a former State Secretary. The recognition as 131er failed because the competent administrative court ruled on March 25, 1960 that Ganzenmüller had no residence in the Federal Republic of Germany on March 31, 1951 and December 31, 1952 . A follow-up insurance as an employee for his work at the Reichsbahn until 1945 had to be taken over by the Deutsche Bundesbahn . Ganzenmüller's attempt to be employed by the Deutsche Bundesbahn failed. From 1947 to 1955 he advised the Argentine state railways, which were only nationalized by President Juan Perón in 1946 . According to his own statements, the focus was on planning a third, southern transand railway to Chile and electrification of the Argentine rail network, for which he was a member of a corresponding planning committee of the Argentine Ministry of Transport. After Peron's fall, Ganzenmüller returned to Germany in 1955. From 1955 until he retired on April 1, 1968, Ganzenmüller worked as a transport specialist for Hoesch AG in Dortmund .

Prosecution

After through the publication of the book The Final Solution. Hitler's attempt to exterminate the Jews of Europe 1939-1945 (English 1953 German: 1956) by Gerald Reitlinger was revealed the correspondence between Ganzenmüller and Wolff again filed the SPD - Bundestag deputy Adolf Arndt in 1957 a criminal complaint against Ganzenmüller. On January 4, 1958, at the request of the Dortmund public prosecutor's office, a preliminary judicial investigation began on the grounds of “suspected complicity in murder ”. By order of the 7th criminal chamber of the Dortmund Regional Court on March 2, 1959, Ganzenmüller was suspended for lack of evidence.

On May 25, 1961, the central office in Ludwigsburg began the investigation. In a final report on February 8, 1962, it was stated that Ganzenmüller had been involved in a leading position "in the implementation of the large transports to the Polish extermination camps" and had helped by accelerating the rail transports. A complaint by the writer Thomas Harlan led to a preliminary investigation that was closed on August 12, 1966 in Dortmund for lack of evidence.

In 1962 Karl Wolff, Ganzenmüller's negotiating partner for the deportation of Jews, was arrested and sentenced in September 1964 to 15 years in prison for aiding and abetting the murder of 300,000 Jews. The evidence against Wolff presented by the public prosecutor's office included the correspondence between Ganzenmüller and Wolff. In reporting on the trial, Der Spiegel quoted Wolff's correspondence with Ganzenmüller in 1962. Der Spiegel also noted that the document had been known since 1947 and that Wolff had no knowledge of the Holocaust .

In his book Eichmann und accomplices (1961), Kempner described Ganzenmüller's participation in the deportations. In 1964, he briefly repeated this in an article for Der Spiegel .

In 1969, criminal proceedings followed against Ganzenmüller because of his involvement in deportations, in which the charges were brought by the Düsseldorf Public Prosecutor Alfred Spieß . Ganzenmüller came around the turn of the year 1969/70 in custody . For a deposit of 300,000 DM , which he a bank guarantee in Oberjoch in Bad Hindelang turned, he was released. In December 1970, this criminal case initially failed. The Düsseldorf regional court refused to open the main proceedings, since Ganzenmüller could not be proven that he "considered it possible that the Jews were exterminated according to plan". Before the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court , the public prosecutor obtained on June 2, 1971 that the proceedings were allowed. The OLG ruled that "in view of his position, his intelligence and the status of his information [...] there was sufficient reason to assume that he had come to the correct conclusions", i. H. he assumed the planned murder of the transported Jews. A witness from Ganzenmüller's antechamber had confirmed that he had spoken to her about the murder of the Jews in Auschwitz.

This last trial against Ganzenmüller began on April 10, 1973, also before the Düsseldorf Regional Court. He was accused of still, by the transport knowingly to murder of Jewish children, women and men and to imprisonment with fatal consequences for quality of service. According to the indictment, Ganzenmüller was responsible for operating the trains from July 1942 to autumn 1944, with which well over a million Jews were transported to the Auschwitz , Belzec , Lublin , Sobibor and Treblinka extermination camps . In court he claimed that he was not aware of the extermination of the Jews. In Poltava he had heard nothing of the shooting of Jews and he never noticed yellow stars . He had "not taken in" the secret letter he signed to Wolff "inwardly and spiritually" and paid no attention to the process. The historian Günter Neliba states that all protective claims , gaps in memory or alleged ignorance of Ganzenmüller “could not absolve Ganzenmüller of aiding and abetting during certain phases of the extermination campaign”. "His willing, supportive intervention in the transport process [...] led to a smooth flow of journeys to the extermination camps."

In addition to Ganzenmüller-Wolff's correspondence, Himmler's diary notes, telexes from various agencies, minutes of a meeting of the government of the Generalgouvernement under Hans Frank and statements by Adolf Eichmann at his trial in Jerusalem (1961) served as evidence.

Ganzenmüller was the only Reichsbahner against whom charges were brought against him for participating in deportations; no further proceedings against Reichsbahner and members of the Gedob were charged.

Last years

On April 29, 1973 Ganzenmüller suffered a heart attack . The proceedings were initially temporarily discontinued due to the inability to stand trial and finally discontinued on March 2, 1977 on the basis of an expert report by the Ulm University Hospital , which had been checked by the Forensic Medical Committee of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia. The national press, such as Der Spiegel and the Stuttgarter Zeitung , also reported on the process .

Ganzenmüller spent the following years in his specially secured apartment in Munich as well as in his house in Bad Hindelang , OT Oberjoch , and was considered vigorous until he was 90.

state of research

So far there is no comprehensive biography of Ganzenmüller. Alfred Gottwaldt has compiled the essential information about his life in the form of a short biographical sketch. Günter Neliba presented another short study on Ganzenmüller as part of his work on the state secretaries of the Nazi government.

Despite his position on the management level of the RVM, Ganzenmüller was little known outside of the Reichsbahn during the war . This became clear, among other things, when the Americans searched for him, which was unsuccessful due to the wrong first name. For the first time, the role of the Reichsbahn and thus Ganzenmüller's activity aroused scientific interest through the work of Gerald Reitlinger . The correspondence between Ganzenmüller and Wolff published by Reitlinger led to the initiation of proceedings against Ganzenmüller, but for the time being the scientific interest continued to focus on Wolff and the SS. Beyond the work and studies in the context of the criminal proceedings against Ganzenmüller, the interest in contemporary historical research remained limited . Wolfgang Scheffler's 1973 report for the last trial against Ganzenmüller is still an essential source for all further work. Many works on the history of the Reichsbahn during the war were written by former Reichsbahn employees in the first decades after the war and were limited to the appreciation of the fulfillment of duties and work performance of the railway workers, for example the work of Pischel and Kreidler. The role of the Reichsbahn in the transport of Jews was often not mentioned. A study on the history of the railway from 1941 to 1945, published by Hugo Strossenreuther on behalf of the Deutsche Bundesbahn , hardly said a word about deportations.

It was only Raul Hilberg who, with his study on the essential role of the Reichsbahn in the Holocaust, also published in German in 1981, was able to draw a little more attention to the people involved in the Reichsbahn and RVM at the time. In 1985, Heiner Lichtenstein published another work based on the files of the Ganzenmüller proceedings, which aroused renewed interest in the role of the Reichsbahn and its management staff during the Holocaust and which in the first place sparked a more intense debate about the officials of the RVM. In addition to the work of Hilberg and Lichtenstein, the studies by Alfred Gottwaldt and the American historian Alfred C. Mierzejewski , which deal with the role of the Reichsbahn and its management personnel, should be mentioned.

Fonts (selection)

- The construction and profitability of rail-road vehicles. Diss. TH Breslau, Reichsbahn-Zentralamt, Munich 1934.

- Is there a renaissance of the rails coming? in: Nahverkehrspraxis 4 (1956), pp. 311-315.

- The Argentine Railways. Economic and technical series of publications published by Ernst Arnold, Dortmund-Mengede 1957.

- The amphibious transport with special consideration of the mass transport. In: Glasers Annalen für Gewerbe und Bauwesen 84 (1960), pp. 28–34.

literature

- Alfred Gottwaldt : Dorpmüller's Reichsbahn. The era of the Reich Minister of Transport Julius Dorpmüller, 1920–1945. EK-Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 2009, ISBN 978-3-88255-726-8 .

- Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: “Jews are prohibited from using dining cars”. The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945. Research report, prepared on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development. Hentrich & Hentrich, Teetz 2007, ISBN 978-3-938485-64-4 ( series of publications by the Centrum Judaicum , 6).

- Raul Hilberg : Special trains to Auschwitz. Dumjahn, Mainz 1981, ISBN 3-921426-18-9 ( documents on railway history , 18).

- Heiner Lichtenstein : With the Reichsbahn into death. Mass transports into the Holocaust 1941–1945. Bund-Verlag, Cologne 1985, ISBN 3-7663-0809-2 .

- Günter Neliba : State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. In: Ders. State secretaries of the Nazi regime. Selected essays . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11846-4 , pp. 73-99.

Archival material

- Wolfgang Scheffler's estate in the Federal Archives contains the expert opinion on Ganzenmüller's responsibility for the criminal trial which was broken off in 1973

Web links

- Literature by and about Albert Ganzenmüller in the catalog of the German National Library

- Ganzenmüller letter

- Concentration camp trains on the Heidebahn, Chapter 14

- Technology museum

- Newspaper article about Albert Ganzenmüller in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ganzenmüller's résumé. From: The Reichsbahn. Official newsletter of the Deutsche Reichsbahn (1942), No. 22/23, p. 192; reproduced in Hilberg: special trains to Auschwitz. Mainz 1981, p. 161, Annex 17.

- ^ Raul Hilberg: Special trains to Auschwitz. Mainz 1981, p. 161.

- ↑ Kösener Corpslisten 1996, 137 , p. 511.

- ^ A b Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are not allowed to use dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945 (Centrum Judaicum series of publications, Volume 6). Teetz 2007, p. 105.

- ↑ Appointment proposal for promotion from Reichsbahnrat to Reichsbahnoberrat from October 27, 1938, printed in: M. Friedman: Zwei different judgments in German courts. Self-published by the Institute of Documentation in Israel, Haifa 2002.

- ^ Alfred C. Mierzejewski: The most valuable asset of the Reich. A history of the German National Railway. Vol. 2, 1933-1945 . University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 2000, ISBN 0-8078-2574-3 , p. 106; Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, p. 87.

- ^ A b Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are not allowed to use dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945 (Centrum Judaicum series of publications, Volume 6). Teetz 2007, p. 106.

- ^ Raul Hilberg: Special trains to Auschwitz. Mainz 1981, p. 163; Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, p. 86.

- ^ A b Raul Hilberg: Special trains to Auschwitz. Mainz 1981, p. 163.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: Dorpmüller's Reichsbahn. The era of the Reich Minister of Transport Julius Dorpmüller 1920–1945. EK-Verlag, Freiburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-88255-726-8 , p. 193.

- ^ Raul Hilberg: Special trains to Auschwitz. Mainz 1981, p. 162.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are prohibited from using dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945 (Centrum Judaicum series of publications, Volume 6). Teetz 2007, p. 108.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand: The Deutsche Reichsbahn in the National Socialist dictatorship 1933-1945 . In: Lothar Gall, Manfred Pohl (Hrsg.): The railway in Germany. From the beginning to the present. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-45817-3 , p. 231.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand: The Deutsche Reichsbahn in the National Socialist dictatorship 1933-1945 . In: Lothar Gall, Manfred Pohl (Hrsg.): The railway in Germany. From the beginning to the present. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-45817-3 , p. 232.

- ↑ Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, pp. 83–85.

- ^ A b Alfred Gottwaldt: Dorpmüller's Reichsbahn. The era of the Reich Minister of Transport Julius Dorpmüller 1920–1945. EK-Verlag, Freiburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-88255-726-8 , p. 192.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand: The Deutsche Reichsbahn in the National Socialist dictatorship 1933-1945. In: Lothar Gall, Manfred Pohl: The railway in Germany. From the beginning to the present. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-45817-3 , p. 230.

- ^ Raul Hilberg: The annihilation of the European Jews. Frankfurt a. M. 1990, p. 429.

- ↑ Götz Aly, Susanne Heim: Vordenker der Vernichtung. Frankfurt a. M. 1993, p. 59.

- ^ A b c d Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are not allowed to use dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945 (Centrum Judaicum series of publications, Volume 6). Teetz 2007, p. 110.

- ↑ Hasso Ziegler: Heard nothing, saw nothing, didn't care. "I mean, for me as a simple citizen ..." From the interrogation of the former State Secretary Albert Ganzenmüller, who was accused of aiding in the extermination of the Jews. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung. No. 96 of April 26, 1973 as an attachment at Hilberg: Special trains to Auschwitz. Mainz 1981, p. 242 f.

- ^ Alfred B. Gottwaldt: German War Locomotives 1939–1945: Locomotives, wagons, armored trains and railway guns. 3. Edition. Franckh'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-440-05160-9 , p. 46.

- ↑ a b Alfred Gottwaldt: Dorpmüller's Reichsbahn: The era of the Reich Minister of Transport Julius Dorpmüller 1920–1945. EK-Verlag, Freiburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-88255-726-8 , p. 195.

- ^ A b Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, p. 89.

- ^ A b Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, p. 90.

- ↑ Helmut Heiber: files of the party chancellery of the NSDAP: Reconstruction of a lost inventory: Regesten. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1983, p. 806 ( accessed online on January 28, 2013).

- ↑ Martin Moll: Control instrument in the "office chaos"? The meetings of the Reich and Gauleiter of the NSDAP . In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , Vol. 49 (2001), Issue 2, pp. 250-252 ( PDF ).

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: Dorpmüller's Reichsbahn. The era of the Reich Minister of Transport Julius Dorpmüller 1920–1945. EK-Verlag, Freiburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-88255-726-8 , p. 207.

- ^ Klaus D. Patzwall : The golden party badge and its honorary awards 1934-1944 (studies of the history of awards, volume 4). Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-931533-50-6 , p. 69.

- ^ A b Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are not allowed to use dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945 (Centrum Judaicum series of publications, Volume 6). Teetz 2007, p. 109.

- ↑ Helmut Heiber: files of the party chancellery of the NSDAP: Reconstruction of a lost inventory: Regesten. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1983, p. 806 ( accessed online on January 28, 2013).

- ↑ a b Klaus Hildebrand: The Deutsche Reichsbahn in the National Socialist dictatorship 1933–1945. In: Lothar Gall, Manfred Pohl: The railway in Germany. From the beginning to the present. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-45817-3 , p. 232.

- ^ Goebbels' diary entry on September 23, 1944.

- ↑ a b Andreas Ewert, Susanne Kill (Ed.): Special trains in death. The deportations with the Deutsche Reichsbahn. Documentation from Deutsche Bahn AG. Böhlau, Cologne 2009, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: Hitler and the Genesis of the "Final Solution". On the occasion of David Irving's theses. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 25 (1977), p. 765 f. ( PDF ).

- ^ A b Raul Hilberg : Special trains to Auschwitz. Ullstein, Mainz 1981, ISBN 3-921426-18-9 , p. 177.

- ↑ Clemens Vollnhals (Ed.): Nazi Trials and the German Public: Occupation, Early Federal Republic and GDR. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011, p. 328 ( accessed online on January 29, 2013).

- ↑ Andreas Ewert, Susanne Kill (Ed.): Special trains in the death. The deportations with the Deutsche Reichsbahn. Documentation from Deutsche Bahn AG. Böhlau, Cologne 2009, p. 58.

- ^ Friedemann needy , Christian Zentner : The great lexicon of the Third Reich. 1992, ISBN 3-89350-563-6 .

- ↑ Tobias Bütow, Franka Bindernagel: A concentration camp in the neighborhood: the Magdeburg satellite camp of the Brabag and the "Freundeskreis Himmler". Böhlau Verlag Köln / Weimar 2004, p. 63 ( accessed online on January 26, 2013).

- ^ Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, p. 92 f.

- ↑ Karola Fings : War, Society and Concentration Camps: Himmler's SS Building Brigades. Dissertation. Schöningh, 2002, p. 229.

- ↑ spurensucheharz.de: Day of Remembrance of the Victims of National Socialism ( Memento from June 20, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on January 28, 2013.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand: The Deutsche Reichsbahn in the National Socialist dictatorship 1933-1945. In: Lothar Gall, Manfred Pohl: The railway in Germany. From the beginning to the present. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-45817-3 , p. 234.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: Dorpmüller's Reichsbahn. The era of the Reich Minister of Transport Julius Dorpmüller 1920–1945. EK-Verlag, Freiburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-88255-726-8 , p. 222.

- ↑ Christopher Kopper , Helmuth Trischler: The railway in the economic miracle: Deutsche Bundesbahn and transport policy in post-war society. Campus Verlag, 2005, p. 34 ( online ).

- ^ Klaus-Dietmar Henke: The American occupation of Germany. Oldenbourg Verlag, p. 437 ( accessed online on January 28, 2013).

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt: Dorpmüller's Reichsbahn. The era of the Reich Minister of Transport Julius Dorpmüller 1920–1945. EK-Verlag, Freiburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-88255-726-8 , p. 223.

- ↑ a b c d e Heiner Lichtenstein: Kill, then travel. In: Jungle World. 51, December 20, 2006 ( online at: hagalil.com ).

- ^ A b c Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, p. 93.

- ^ A b Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are not allowed to use dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945. Teetz 2007, p. 111.

- ↑ Christopher Kopper, Helmuth Trischler: The railway in the economic miracle. German Federal Railways and Transport Policy in Post-War Society. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 2005, p. 51 ( online ).

- ^ Raul Hilberg: The annihilation of the European Jews. Frankfurt a. M. 1990, p. 1169. With the year 1947 to 1955.

- ^ Albert Ganzenmüller: The Argentine Railways. Economic and technical series of publications published by Ernst Arnold, Dortmund-Mengede 1957, pp. 11, 12.

- ^ Andreas Eichmüller: No general amnesty: The prosecution of Nazi crimes in the early Federal Republic. Oldenbourg Verlag, 2012, p. 363 ( accessed online on January 24, 2013).

- ↑ Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, p. 94. The correspondence was already registered as a document in the Nuremberg Process Economic and Administrative Main Office of the SS . (NO 2207, NO 2405). Neliba, Kleinmann and Ganzmüller , p. 91.

- ^ Foreword by Adalbert Rückerl in Hilberg: Special trains to Auschwitz. Mainz 1981, p. 14.

- ^ SS General Wolff. Himmler's little wolf . In: Der Spiegel . No. 7 , 1962, pp. 37-39 ( Online - Feb. 14, 1962 ).

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? West German Justice and Politics of the Past in the Sixties. Wallstein Verlag, 2004, p. 244 ( accessed online on January 27, 2013).

- ^ Robert MW Kempner: NS death sentences went unpunished . In: Der Spiegel . No. 16 , 1964, pp. 33-35 ( Online - Apr. 15, 1964 ).

- ↑ a b c Kindly informed . In: Der Spiegel . No. 14 , 1973, p. 62-63 ( Online - Apr. 2, 1973 ).

- ↑ Andreas Engwert (Ed.): Special trains in the death - The deportations with the Deutsche Reichsbahn (documentation accompanying the traveling exhibition of the same name). Cologne 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-20337-5 , p. 61.

- ^ Hasso Ziegler: Ganzenmüller accused of complicity in murder. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung. April 3, 1973 as a facility near Hilberg: special trains to Auschwitz. Mainz 1981, p. 234 f.

- ^ A b Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, p. 94 f.

- ^ Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the Nazi Reich Ministry of Transport from 1937. Berlin 2005, p. 99.

- ↑ Anonymous article presumably by Hasso Ziegler: The jury court presents an almost complete chain of circumstantial evidence. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung. April 13, 1973. Reproduced in Hilberg: Special trains to Auschwitz. Mainz 1981, p. 241, Annex 64.

- ^ Raul Hilberg: Special trains to Auschwitz. Ullstein 1987, p. 11, foreword by Adalbert Rückert.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are prohibited from using dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945. Research report. Teetz 2007, ISBN 978-3-938485-64-4 , p. 112.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are prohibited from using dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945. Research report, prepared on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development. Hentrich & Hentrich, Teetz 2007, ISBN 978-3-938485-64-4 , pp. 105–112 ( Centrum Judaicum 6 series).

- ^ Günter Neliba: State Secretary Kleinmann and successor Ganzenmüller in the NS Ministry of Transport from 1937. In: Ders .: State Secretaries of the NS regime. Selected essays. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, pp. 73-99.

- ↑ To be mentioned above all: Gerald Reitlinger: The Final Solution: Hitler's attempt to exterminate the Jews of Europe 1939–1945. 7th edition. Colloquium Verlag, Berlin 1956, ISBN 3-7678-0807-2 (translated by J. W. Brügel).

- ^ A b c Alfred Gottwaldt: The Reichsbahn and the Jews 1933–1939. Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ Werner Pischel: The General Direction of the Eastern Railway in Krakow: 1939-1945, a contribution to the history d. German railways in World War II.

- ↑ Eugen Kreidler: The railways in the sphere of influence of the Axis powers during the Second World War. Commitment and performance for the Wehrmacht and the war economy (studies and documents on the history of the Second World War, 15). Musterschmidt Verlag, Göttingen 1975.

- ^ Review of Kreidler's study by A. Gottwaldt.

- ^ Documentation service of the Deutsche Bundesbahn and Hugo Strossenreuther (Ed.): Railways and Railway Workers between 1941 and 1945 (Documentary Encyclopedia, Vol. 5). Frankfurt am Main 1973.

- ^ A b Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: "Jews are not allowed to use dining cars". The anti-Jewish policy of the Reich Ministry of Transport between 1933 and 1945. Teetz 2007, p. 15.

- ^ Alfred C. Mierzejewski: The Most Valuable Asset of the Reich. A History of the German National Railway. Volume 1, 1920-1932 ; Volume 2, 1933-1945 . The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 2001, ISBN 0-8078-2496-8 (Volume 1) ISBN 0-8078-2574-3 (Volume 2).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ganzenmüller, Albert |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German civil servant, State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of Transport |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 25, 1905 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Passau |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 20, 1996 |

| Place of death | Munich |