Free trade unions (Germany)

In Germany, free trade unions are the socialist- oriented trade union organizations of the 19th and 20th centuries. The term "free" is an addition that has emerged over time to distinguish the organizations from the competing liberal Hirsch-Duncker trade unions on the one hand and the Christian trade unions on the other. In Austria , too , the socialist organizations were called free trade unions for the same reason .

After precursors, socialist or social democratically oriented unions have developed since the 1860s, both in the environment of the General German Workers 'Association (ADAV), which is actually trade union skeptical, and the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP). The two directions united in 1875. The Socialist Law of 1878 marked a deep break that set back development . A new structure took place while the law was still in force. But only after its abolition in 1890 could the free trade unions develop into a mass organization. The previous individual organizations merged in 1890 to form the General Commission of the German Trade Unions . The free trade unions developed to the largest membership union direction . Within the social democratic labor movement they formed a basis for a reforming wing. In 1906 the trade unions enforced equality between the party and the trade unions against the SPD .

During the First World War they supported the government's civil peace policy . With the Auxiliary Services Act , the unions were recognized by the state as professional representatives of the workers' interests. Shortly after the beginning of the November Revolution, they agreed the Stinnes-Legien Agreement with employers, which also earned them recognition of employers as negotiating partners.

At the beginning of the Weimar Republic , the organization of free trade unions was renamed General German Trade Union Federation . Before the First World War, the General Commission helped to organize the (few) social democratic-oriented employees, but in 1920 the General Free Employees' Association (AfA-Bund) was founded. In 1924 the General German Association of Officials (ADB) was founded. Both this organization of civil servants and the AfA-Bund were loosely connected to the ADGB. One spoke at the time of the "three-pillar model" of the workers' movement.

The free trade unions reached their peak in importance in the early 1920s. During this time they reached their highest membership numbers. The general strike of the trade unions contributed significantly to the suppression of the Kapp putsch . During the period of inflation , the organization fell into a deep crisis. After a phase of recovery, the global economic crisis was linked to another weakening of the free trade unions. In the early days of National Socialist rule , the leaders of the free trade unions tried to keep the organization alive and adapted to the new regime. This did not prevent the free trade unions from being smashed immediately after “National Labor Day” ( May 1st ) 1933.

Early days

The first union-like approaches already existed in the pre-March period . The Gutenberg Association was founded in 1846 by Leipzig book printers . The printer was an important group of the early labor movement later on. They could look back on an old organizational tradition. In 1848, principals and journeymen founded a joint national book printer association before, after labor disputes, an organization of journeymen was formed with the Gutenbergbund in 1849. Stephan Born , who came into contact with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in Paris and became a member of the League of Communists , also emerged from the printing environment .

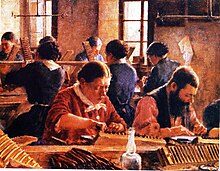

The second group that organized nationally at a particularly early stage were the cigar workers. During the revolution of 1848 the first cigar workers' congress took place on September 25, 1848, at which a central organization was founded with the Association of Cigar Workers in Germany . In some cases, it was still based on the professional policy of the guilds. In addition, minimum wages and collective agreements have already been demanded. In 1849, 77 locations were represented in this association. The organizations were able to build on existing support and educational associations.

While the League of Communists, with its main focus on the Rhineland , took care of programmatic issues during the revolution, the General German Workers' Brotherhood founded by Stephan Born in Berlin became the real origin of the organized labor movement. Even if masters were still organized in it, it made demands to improve the situation of the workers. These included, for example, minimum wages and a regulation of working hours, but also the demand for freedom of association . These and other points were later also among the important demands of the trade union workers' movement.

Organized by Born among others, a general workers' congress took place in Berlin . In the appeal in Born's magazine Das Volk it was said:

"Let us unite, who up to now have been weak and unconsidered in terms of isolation and fragmentation. We count millions and form the great majority of the nation. Only united in equal striving will we be strong and attain that power which is due to us as the producers of all wealth. Our voice is a heavy one and we will not fail to put it on the scales of social democracy. "

Ultimately, the various approaches to the emergence of a labor movement in the reaction era could not hold up. In 1850, the printers and tobacco workers union and the workers' fraternity were banned.

However, there were still labor disputes at the local level, partly linked to organizations from the revolutionary era . In 1850 around 2,000 cloth workers went on strike in Lennep . There had been a workers' association there during the revolution, which had broadcast to other places in the Bergisches Land . Before the strike, a new club could be established in Lennep. The movement was suppressed militarily. Labor disputes in Elberfeld and Barmen in 1855 and 1857 were similar . In general, the strike has gradually established itself as a method of enforcing material interests during this period. In 1857 alone there were 41 strikes. The police did not succeed in banning all mergers. At the local level, some organizations continued to exist or were newly formed as support funds or educational and social associations.

Development up to the end of the socialist law

Requirements for forming a union

In Prussia in the 1860s, during the so-called New Era, the conditions for workers' organizational aspirations improved . In the time of the constitutional conflict, left liberalism and the bourgeois democrats wooed the workers. From this environment, the labor movement was strongly promoted, especially in the form of workers' education associations. It is estimated that between 1860 and 1864 225 workers' and craftsmen's associations were established.

Gradually, however, there were efforts to develop independent organizations independent of the bourgeoisie. As such, the General German Workers' Association (ADAV) was established in 1863 . In addition, the Association of German Workers' Associations (VDAV) came into being, initially still associated with left-wing liberalism . In 1868 August Bebel and Karl Liebknecht transformed it into a workers' organization. During this time, the labor movement was divided into two parts: party and union. The party prevailed in Germany until the end of the 19th century. In Britain, on the other hand, unions had become powerful organizations long before the Labor Party was formed around the turn of the century . In Germany it was the other way around. First, workers' parties emerged, and only then were unions dependent on them. The party liked to view the unions as secondary schools for their offspring.

An important prerequisite for the creation of permanent trade union organizations had the right of association . In Prussia there had been a legal ban on coalitions since 1845, which was tightened in 1854. In 1860 state control over employment relationships in the mining industry finally ended. The coalition ban was expressly anchored in the mining law of 1865. Not only in working-class circles, but also among social reformers like Gustav Schmoller , the coalition ban was viewed increasingly critically. In particular from left-wing liberal circles there were attacks against the ban on mergers. In the Kingdom of Saxony , the ban on coalitions fell in 1861, when Prussia began to adopt a more relaxed approach in 1867, before the trade regulations of the North German Confederation in 1869 expressly granted the right of association.

The time when socialist trade unions were formed

While Axel Kuhn is of the opinion that the unions were founded by the parties, Klaus Schönhoven emphasizes that the original impulses for the establishment of a union did not come from the parties, but that they developed autonomously. Both ADAV and VDAV took up these efforts hesitantly at first in order to strengthen their base. The establishment of trade unions by the ADAV actually contradicted the wage law as a central component of the party ideology. This means that wage increases achieved through strikes or similar measures would immediately be canceled out by the market. A union with the aim of pushing through wage increases would therefore make no sense. The party argued that unions were useful in raising awareness and therefore useful. The consequences of the parties' engagement were ambivalent. On the one hand, they accelerated the process of mobilization, on the other hand, the unions got caught up in political conflicts.

As in 1848, the cigar workers and book printers started with the establishment of central associations. The cigar workers founded an association in 1865 under the direction of Friedrich Wilhelm Fritzsche . The book printers had already founded a Central German Book Printers Association in 1863. The so-called threepenny strike in Leipzig triggered a Germany-wide wave of solidarity and the inflow of numerous donations from other industries. The strike defeat increased the urge to unite across Germany. At the first Buchdruckertag in Leipzig in 1866, 84 local associations with around 3000 members were represented. Richard Härtel took over the management of the printing movement in 1867 , and in 1868 an umbrella organization of regional district associations was founded. The Association of German Book Printers was more closely related to the VDAV, but initially stayed out of party-political conflicts. In 1869 it had about 6,000 members in 426 locations, which were organized in 41 district associations. The General German Tailors' Association was also one of the early central associations. He was also close to the ADAV and in 1869 had around 3,000 members. The early organizations consisted primarily of qualified and mostly skilled workers in small to medium-sized companies. They were mostly younger men between 20 and 30 years of age. Older people and women initially played no role.

The breakthrough of the trade union movement took place in 1868. The long-lasting good economic situation of the early days played an important role. The workers also wanted to benefit from the growing prosperity. In the VDAV, Bebel and Liebknecht had largely prevailed and established the connection to the International Workers' Association . Following the Association Day in Nuremberg in 1868, Bebel called for the establishment of international trade unions . At the same time, Bebel published a model statute. This envisaged a democratic structure from the bottom up. The establishment took place from the local cooperatives through the district associations to the central board. Particularly at the beginning, some organizations followed the “on-site principle.” One place temporarily became the seat of the association and the local board acted as the board for the overall organization. Annual general assemblies were held at which the management board and a supervisory body ( control commission ) were elected. In principle, this type of structure is still valid today. In the fall of 1869 the membership should have been around 15,000. In the meantime, the Social Democratic Workers' Party had also been founded, to which the trade unions can be assigned. However, there was still no umbrella organization.

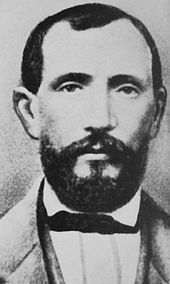

Johann Baptist von Schweitzer as the new ADAV President feared that the formation of a union by the VDAV would reduce the attraction of the ADAV. In great haste he convened a General German Workers' Congress in Berlin in September 1868 to found his own trade unions. He acted deliberately against the Lassallean dogma and accepted the splitting off of an orthodox wing around Fritz Mende and Countess Hatzfeld . In fact, nine of the twelve planned workers for various professions and industries were established at the congress .

As a result, there was criticism of the unions within the party, which contributed to the decline of the organization. On the other hand, the displeasure about a lack of internal democracy caused some associations to switch to the camp of the trade unions. In 1870 the workers 'unions were then merged into the workers' support association. The abandonment of the professional principle in favor of a unitary association met with resistance. At the beginning of the 1870s the labor force still had around 21,000 members. In 1871 there were just 4,200 members.

Incidentally, the left-liberal Hirsch-Duncker trade unions with around 16,000 members were founded in 1868 in mid-1869. However, the left-liberal trade unions found little support in the ranks of the Progress Party . In the Catholic camp, Christian social workers' associations emerged in the Rhenish-Westphalian region, which at this time also pursued union-political goals. In the 1880s, what was left was absorbed by the Catholic workers' associations, which were no longer unionized . In this respect, it was already becoming apparent at this point in time that there was a split into unions .

Unions in the early days

Theodor York could not prevail with his idea of a party-political neutrality of the trade union movement, although it was advocated by the leading trade union theorist Carl Hillmann at the time . York also unsuccessfully proposed a union of the various professional unions so that the financially weak organizations could support each other if necessary. This was also a reaction to the stagnating development of the organizations after the establishment of the empire. In Berlin, localist competition developed with the Berlin Workers' Union . The new ADAV President Carl Wilhelm Tölcke even wanted to dissolve the unions again, but was unable to fully assert himself in his own ranks. Another problem was that numerous union members had to do military service in the Franco-German War . This weakened financial strength, and national enthusiasm weakened approval of all social democratic organizations. Four out of ten trade unions did not survive 1870.

Despite this organizational stagnation, there were numerous strikes in the early years due to the good economic situation. On Waldburger miners' strike in 1869/70 to about 7,000 workers took part. In 1872 there were at least 362 strikes with around 100,000 participants. In the spring of 1873, for example, the printers fought over a collective agreement. The strikes in the construction sector were particularly numerous. A miners' strike broke out in the Ruhr area in 1872 . Ultimately, 21,000 miners were involved in this, and it is considered the first mass strike in German history. The attempt to subsequently found a union failed, not least because of resistance from employers and the state. Incidentally, the strike wave around 1872 was not limited to Germany; there were also a number of labor disputes in other countries. Numerous industries were involved in Germany. Apart from the big cities, Prussia, Saxony and northern Bavaria in particular were affected by it. These strikes gave a boost to the development of the unions as a whole.

Regional focal points of the early unions were central Germany , the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial area , as well as large cities such as Leipzig , Berlin, Hanover and Hamburg . The total number of union members is estimated to be around 60,000 to 70,000 in 1870-71. This would correspond to an organization level of 2 to 3 percent.

Tessendorf era and striving for unification

In 1874 the start-up crisis followed the start-up boom . It was not until the 1890s that a longer period of boom set in again. In some cases, labor incomes fell dramatically, and the weak economy greatly reduced the chances of success in labor disputes. Overall, the entrepreneur's ability to assert himself increased. This was at least partially supported by politics under Otto von Bismarck . In 1873 he submitted the so-called breach of contract draft as a supplement to the Reichsgewerbeordnung , which restricted the right of association. However, the bill also failed in the Reichstag due to the resistance of the National Liberals . In the Tessendorf era, named after the public prosecutor Hermann Tessendorf , the persecution of workers' organizations began in 1874, especially in Prussia, but also in other federal states.

From the workers 'point of view, given the increased employers' power and state repression, the Marxist interpretation of the class state and class struggle seemed increasingly plausible. Marxism prevailed as an ideology until 1890. The experience of state persecution in the 1870s / 80s left a lasting mark on at least one generation of workers' leaders. It also resulted in the party and trade unions becoming even closer to one another. The idea that the trade unions are subordinate to the party solidified.

The growing state pressure also led to the unification of the two workers 'parties to form the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (SAP) in 1875 and thus to an end to the conflicts between the two camps. In the longer term, the ADAV's anti-union stance lost weight in the new party. A trade union conference was also held there after the Gotha unification convention in 1875. It was decided that they wanted to keep politics out of the unions. The actual unification of the associations took longer than expected, but was ultimately successful.

Centralization made less progress overall. The fact that Theodor Yorck, the real engine of centralization, died in 1875 also played a role. These efforts were carried on by August Geib and others. Various attempts were made to found an umbrella organization, but several congresses could not take place for various reasons.

Organizational structure around 1878

Statistics compiled by August Geib in 1877/78 give an insight into the structure of the social democratically oriented trade unions before the Socialist Law. The strongest organization with 8100 members was that of the tobacco workers. This was followed by book printers (5500), joiners (5100), metal workers (3555), shoemakers (3585), carpenters (3300), ship carpenters (3000), tailors (2800), hat makers (2767), bricklayers (2500) and factory workers (1800 ). There were also a number of smaller associations with fewer than 1,000 members. Geib had a total of around 50,000 members. For the year 1878 one assumes an increase to 60,000 members. The craftsmen dominated . Until the end of the empire, the farm workers could not be organized . In mining there was only a stable association in Saxony. In the Ruhr region , there were Christian social aspirations, but failed 1878th The success of the textile workers and the less qualified factory workers was relatively low. The manual trades dominated the metalworkers. The number of employees in heavy industry was significantly lower . Overall, the structure has hardly changed compared to the early years of the trade unions. The unions were organized according to the club model, company organizations basically played no role. This was also one of the reasons why syndicalism only played a minor role in Germany.

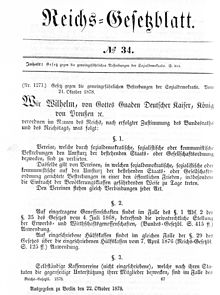

Under the socialist law

The free trade unions were also severely affected by the Socialist Law , which was directed against all social democratic, socialist or communist associations. Some unions, such as bricklayers, disbanded themselves to protect cash and other property from confiscation. Numerous trade unions and local professional associations were banned in 1878/79. The same was true of numerous union newspapers. The printer's association and the Hirsch-Duncker trade unions remained because of their non-social-democratic character. Other unions turned into support associations and some of them could continue to exist. According to an estimate by Ignaz Auer , 17 central associations, 78 local associations, 23 relief funds and a number of other associations were banned while the Socialist Act was in force. 1299 printed matter were also affected by the law. A total of 831 years' imprisonment was imposed and 893 people were evicted from their homes.

During the years of the Socialist Law, some important structural changes took place. Although the economic slump of the start-up crisis was not completely over, industrial development continued during the period of high industrialization in Germany . Between 1875 and 1890, the number of people employed in the mining and manufacturing industries increased by 30%. After all, more people worked in this area than in agriculture. The introduction of important components of the Bismarck social security system also fell during this period .

In 1879 and 1880 the union movement was largely eliminated. Some active trade unionists preferred emigration to reprisals. Since 1881 the socialist law was then applied less rigorously. A few professional associations began to form, mostly at the local level. In addition, Christian social endeavors intensified.

Central support organizations gradually emerged from local associations. By the end of 1884 there were again thirteen central associations. In 1888 there were a total of 40 associations. On the basis of these associations and local clubs, the trade union movement in 1885 had a similarly high number of members as before the Socialist Act. A total of 775,000 workers belonged to the relief funds in 1885.

As long as there was a purely union effort, this development was tolerated by the authorities. If there were links to the illegal party, that was over. In view of the increasing strike activity, the authorities tightened the course again in 1886. Interior Minister Robert von Puttkamer issued the so-called strike decree. New bans were issued, which particularly concerned the organizational efforts of metal workers and in the construction sector. Nevertheless, there were other foundings. According to official figures, the number of union members in 1888 was 110,000. In 1890 there were 295,000. The largest part belonged to the free trade unions. The Hirsch-Duncker trade associations had up to 63,000 members during this time.

The big strikes in 1889 also made it clear that the socialist law had not succeeded in suppressing the labor movement. The best known is the strike in the Ruhr mining industry , in which 90,000 out of 104,000 miners were involved. An organization of miners also emerged from the strike . The strike also boosted union organization as a whole. In 1890 the socialist law expired. This marked the beginning of a new phase in union development.

Rise to the mass movement

Basic conditions

An essential prerequisite for the boom in trade unionism as a whole was the boom since the 1890s. This continued with economic interruptions until 1914. The Hirsch-Duncker trade unions also benefited from this, and independent Christian trade unions developed from 1894 onwards . During this time, the system of directional trade unions was formed, which was to last until 1933.

Large strikes like the miners 'strike in 1889 in the Ruhr area or the strike in Hamburg in 1890 showed how great the need was to represent workers' interests. The defeat in the Hamburg May fights also showed how little fragmented organizations could do against employers. Individual groups of workers and locally oriented organizations turned out to be too weak to successfully survive long and severe conflicts.

Professional or industrial association?

The clarification of the organizational question was of central importance for the free trade unions. Encouraged by representatives of the metal workers, in particular Martin Segitz from Nuremberg , calls for a nationwide meeting of free trade unions were loud. In November 1890, the participants of a free trade union conference in Berlin debated the future form of organization. There were representatives who stood up for professional associations. This applies, for example, to the book printer or tailor. But there were also advocates of cross-professional organizations as an industrial association. This included some metal workers. The result was a compromise. Professional associations continued to be accepted, but large, inter-professional organizations should also be able to emerge. Both sides could live with that. In the resolution passed in Berlin, the delegates spoke out in favor of organizations throughout the Reich and against local associations. With this, localism as a political and economic organization, which had a relatively large number of supporters, especially in Berlin, was rejected.

The metal workers united in 1891 to form the German Metal Workers' Association (DMV), a cross-professional industrial association. They were followed in 1893 by the German Woodworkers Association . Most of the other unions remained professional associations.

At a conference in Halberstadt in 1891, a majority of the delegates spoke out in favor of a loose association of related professions, without this being implemented in practice. At the Halberstadt Congress in 1892, after controversial debates, it was difficult to get beyond the Berlin resolutions. The professional association principle remained the central organizational basis. At least the professional associations were asked to conclude cartel agreements with each other for the various branches of industry, which did not take place. Congress confirmed the rejection of localism and emphasized the separation of political and trade union organization. This corresponded to the tendencies in the SPD. There, too, people turned against localism and advocated a separation of party and union. As a result, the localist associations were marginalized without having completely disappeared.

The focus on the professional association principle took into account the membership, which still consisted to a large extent of qualified journeyman workers and not yet of unskilled mass workers.

A point of contention within the trade unions was the question of whether, in addition to the payment of support for labor disputes, other support should also be paid in the event of unemployment, illness or disability. Opponents argued that it is not the job of the unions to take the social burden off the state or employers. Such cash registers could also limit performance in industrial disputes. The proponents said that one could bond the members more strongly through support funds. Ultimately, this opinion prevailed.

General Commission

At the Berlin functionaries' conference, the general commission of the trade unions in Germany was also founded as an inter-association coordination and agitation body. The commission initially consisted of seven people. At first she was only active on a temporary basis and was mainly supposed to organize the upcoming congresses. Its members themselves saw the General Commission as a permanent institution from the start. Since 1891 she published the correspondence sheet. This became an important instrument in the internal union opinion-forming process. From the start, the leading figure in the commission was Carl Legien . He had already made a name for himself as a trade unionist in the professional wood turner's association in Hamburg since 1896. Last but not least, he succeeded in giving the General Commission its own weight against criticism, especially from the ranks of the metal workers.

At the Halberstadt Conference of 1891 he succeeded in obtaining permanent funding for the General Commission from the member associations. The Congress of 1892 confirmed the existence of the commission, but at the same time curtailed its powers. It should no longer be responsible for the financial support of defensive strikes. Above all, it should take care of professional groups where the degree of organization was still low. The General Commission kept statistics on the development of membership in the individual affiliated unions and on strike activity. It should also take care of developments in international relations. In a certain way, it was only a service provider bound by instructions for the member associations and not a management organization for the entire free trade unions.

Instead, Carl Legien wanted to transform the commission into a leading body in the long term. The Commission should not only encourage further trade union development, but also launch its own social policy initiatives. In 1894, for example, he initiated a workers' congress that was to deal with topics such as occupational safety, factory inspection, accident insurance and the right of assembly. This triggered a conflict between the trade unions and the SPD. This saw it as an intervention in their previous work area. The party saw its own leadership role in the social democratically oriented labor movement in danger. At this pressure Legien had to cancel the congress.

At the second trade union congress in 1896, the metalworkers' association fundamentally questioned the commission, but was unable to prevail. On the other hand, the Commission's attempt to set up a strike reserve fund managed by it failed. The attempt to bring the industrial action under the control of the General Commission had thus failed. These remained a matter for the individual unions. The commission was only allowed to collect strike money at the request of an individual union.

Nevertheless, the general approval of the General Commission gradually gained acceptance. At the Frankfurt trade union congress in 1899, the right to exist of the commission was undisputed. Congress passed an organizational statute for the commission. Her area of responsibility has also been significantly expanded. So she was now also responsible for social policy issues. This indicated that the trade unions no longer wanted to subordinate themselves to the party, but gradually saw each other as equals.

Relationship between party and union

Development up to the turn of the century

The union-party relationship became a problem for a number of reasons. Although the trade union leaders were Social Democrats and Marxism had established itself as the dominant ideology, self-confidence in the unions had nonetheless grown. Its own rise in the 1880s contributed to this. It was not the party that supported the trade unions during this period, rather it was often the other way around. There was a new generation that had been socialized more in the trade union movement and less in the party.

In the party there was initially no reason to revise the theoretical understanding of the nature and tasks of the trade unions developed before 1870. In the Erfurt program of 1891 the leadership role of the party was again emphasized. The trade unionists accepted this without wanting to be content in the long run with the role of the trade unions as the party's recruiting school. Carl Legien wrote, for example, that the mass of workers could only be won over to the socialist idea through economic struggle "in today's bourgeois society" .

However, at this point he did not want to risk a conflict with the party, as the situation of the unions was critical. Various unions faced financial ruin after their strike defeats. The tobacco workers' union collapsed after being locked out . The miners' association lost numerous members when it left. This crisis of the trade unions confirmed in the SPD the conviction that only political struggle could point the way to socialism.

August Bebel sharply attacked the reformers in the trade unions. He himself hoped for the big "Kladderadatsch" of capitalist society soon and could not gain much from the reform efforts in the imperial state. However, the collapse of capitalism was a long time coming in the following years, while the organizing work of the unions was successful. It is characteristic of the party's distant relationship with the trade unions that no leading party politician attended trade union congresses until the turn of the century.

Equality of party and trade unions

The rapid growth of the trade union movement, the reformism of the trade union leaders, the emergence of revisionism in the SPD and the waning of workers' hopes for revolution forced a clarification of the relationship between party and trade union. The balance of power had meanwhile shifted in favor of the unions. With its 1.6 million members, the free trade unions had a considerable organizational lead over the SPD, which had fewer than 400,000 members.

The different positions became particularly clear in two debates between 1899 and 1906: the neutrality debate and the mass strike debate . The neutrality debate was triggered by some union leaders who, in view of the successes of the Christian unions, pleaded for a greater distance from the SPD. In May 1899, Bebel gave up the party's claim to leadership in a keynote speech, recognized the independence of the trade unions and pleaded for their party-political neutrality. However, he warned against a course away from the SPD. The party theorist Karl Kautsky wrote in a programmatic paper in 1900 on the relationship between the party and the trade unions:

“The political organizations of the proletariat will always comprise only a small elite ; Mass organizations can only form the unions. A social democratic party, whose core troops are not the trade unions, therefore built on sand. The unions must remain outside the party. "

That also dictates

“The consideration of the special tasks of this organization. But social democracy always has to endeavor to ensure that the members of the trade union organizations are filled with a socialist spirit. The socialist propaganda among the unions has to go hand in hand with the propaganda for the unions in the party organization. "

The mass strike debate was about whether the general strike should also be used in deep political conflicts. Especially after the Russian Revolution of 1905 , this topic was on the agenda of the party and trade unions. The leading trade unionists opposed the mass strike because this strategy would have jeopardized the organization and the social advances made by the reform course. The 1905 trade union day in Cologne then rejected the mass strike with a large majority and opposed the syndicalists and the left wing in the SPD. This resolution not only triggered a corresponding backlash from Rosa Luxemburg and other supporters of the mass strike, criticism also came from within.

At the SPD party congress in Jena that same year, Bebel looked for a compromise, but rekindled the debate with his sentence that the mass strike was the “most effective means of combat”. As a result, the party and the trade unions appeared to be on the verge of a break. At the Mannheim party congress of 1906, the so-called Mannheim Agreement was reached : A compromise was found in the actual dispute. It was important that the SPD finally recognized the equality of the unions. It was also agreed to agree on a common course for actions affecting the interests of both sides. In practice this meant that the possibility of a mass strike was also off the table. The debate continued in the party, but it no longer played a significant role in relations with the trade unions.

structure

Membership numbers

As a result of a temporarily faltering economy, the number of members of the free trade unions fell from around 300,000 in 1890 to 1895 by around 50,000. In the following years of economic boom, the number of members rose sharply to 680,427 in 1900. The Hirsch-Duncker trade unions had 90,000 members during this period and the Christian trade unions an estimated 76,000 members. In the following years the membership of the trade unions continued to grow. In 1913 the total was 3 million. A large part of around 2.5 million went to the free trade unions. The Christian trade unions had around 340,000 and the Hirsch-Duncker family 100,000 members.

The growth was closely related to the economic development. During the boom, the number of members increased particularly sharply, while it stagnated in economically weaker years. There were also other factors. Shortly before major labor disputes, membership increased. After the conflict ended, many left the organizations. Before the miners' strike in the Ruhr area in 1905, 60,000 workers joined the union. After the end of the strike, 30,000 left the organization. The fluctuations were a big problem for the organizations. Many new members were looking for the direct benefits of membership, but many were not interested in permanent commitment out of conviction or even in the general program. The uncertain income and living conditions also played a role. In the last few years before the start of the war, the trade unions responded to fluctuation by changing the statutes. Labor dispute support now depended on membership time.

Organizational promoting and inhibiting factors

Sectors, professions and regions differed in their degree of organization, because the respective organizational-promoting or inhibiting factors also differed significantly. As before, the level of organization was particularly high in some craft trades (book printer, coppersmith, glove maker and others). It was very difficult to organize workers in sectors with a high proportion of unskilled workers or women. This applied, for example, to the textile industry, trade or factory work.

There were areas in which the barriers for the unions were particularly high. In addition to the farm workers, these were the increasing numbers of employees in the public sector, for example in the railway or post office. Anti-union measures, restrictions on the right of association, but also special company social benefits prevented the unions from penetrating, especially those with a social democratic orientation. In the agricultural sector, the civil rights , the resistance of the landowners and the difficulty of finding access to the mentality of the rural population prevented the emergence of a noteworthy agricultural labor movement. In 1914, despite great agitation efforts, the agricultural workers' association had only 22,000 members. The free trade unions also had limited access to the growing number of employees . Most of the employees set themselves apart from the workers.

In key areas of industry such as heavy industry , anti-union measures and special company social benefits made it difficult for the unions to gain a foothold there. It was easier for trade unions in highly industrialized and urban areas than in rural areas. Berlin and Hamburg were therefore strongholds of the trade unions. They were relatively strong in central and northern Germany, but relatively weak in southern Germany and the eastern agricultural areas.

Inner structure

With regard to the individual trade unions, the organizations based on the industrial union principle were the most important. Of the 46 central associations of the free trade unions, the German Metalworkers' Association was by far the largest with over 500,000 members. The organizations in the construction, mining, wood and textile industries, the transport industry and the factory workers' association had over 100,000 members. This included very different areas of employment such as the chemical industry, rubber manufacturers or producers of margarine. Overall, the largest associations organized more than two thirds of all members of the free trade unions. The professional associations lagged far behind. These mostly organized individual craft trades. Despite their numerically insignificant size, they held on to their independence.

Against the background of the strong growth in membership but also the high fluctuation figures, the organization became increasingly professional. The number of full-time functionaries increased significantly. In 1898 there were only 104 paid functionaries in the free trade unions, there were already 2867 in 1914. These were mostly employed in the regional sub-divisions to look after the members. Increasingly, questions of labor law or collective bargaining policy required specialists. The tasks in the workers' secretariats , for example , became too complex to be carried out by volunteer officials alongside work. Most of the full-time functionaries themselves emerged from the workforce. Hence the growth of the full-time apparatus did not necessarily mean an alienation between the functionaries and the members.

However, the growth of the trade unions meant that members could no longer actively participate in all decision-making processes. A multi-level delegate system was set up and local decision-making autonomy was restricted. This is especially true for the strike decisions. These could initially still be taken at the local level. This changed in 1899 when a trade union congress assigned the power to strike to the central associations. For this purpose, special statutes were issued and the decision on industrial disputes was reserved to the central boards. This led to tensions in the associations without, however, leading to profound crises or even the disintegration of an organization. The board members did not always have their members completely under control. The shipyard workers' strike of 1913, which broke out against the will of the association, was particularly spectacular. One problem was the organization in local payment offices and the neglect of the company level.

Relations with politics and employers

The political framework conditions were also important for the unions. After Leo von Caprivi's resignation , his conciliatory and social reform policy was given up, not least at the insistence of Wilhelm II . This relied on a policy of confrontation with the labor movement. The so-called prison bill that was launched in this context failed at the Reichstag in 1899. The anti-union policy was a failure. As a result, social legislation experienced numerous new impulses. Considerable progress has been made, among other things, with regard to occupational safety and the right of association. However, the state was far from recognizing the trade unions as the appointed representatives of the workers. The police still used force, for example during strikes. The full right of association was also not achieved. Employers were similarly negative. They fired well-known union members and blacklisted them .

Various developments in the economy hampered the further rise of the trade unions in the years before the First World War. Large-scale cartelized companies could hardly be wounded by strikes. In addition, strong employers' associations emerged. The Crimmitschau strike in 1903 turned into a confrontation between trade unions and employers beyond the local occasion. The strike led to a surge in the organization of employers. Only in a few areas, such as the wood and leather industry and the book printers, did the unions still have an organizational lead over employers before the war.

Especially in core economic areas such as mining, chemical, electrical and heavy industry, employers were superior to unions. In particular, the employers in mining and the coal and steel industry in the Ruhr area, Saarland and Rhineland often insisted on a “gentleman in the house”. Admittedly, this rigor was not so pronounced in other industries. Small and medium-sized company structures also made it easier for the unions to succeed in labor disputes.

The situation was also not clear in other respects. On the one hand, there are major mass strikes and lockouts that have attracted national attention, such as the lockout of construction workers in 1910, the miners 'strike in the Ruhr area of 1912 or the shipyard workers ' strike in the same year. On the other hand, there was a growing number of peaceful conflict solutions. The number of collective agreements increased sevenfold after 1905, even if employers were still able to set wages and working conditions for over four fifths of workers without the involvement of the trade unions. The extent to which the hardliners would have retained the upper hand in the heavy industrial companies in the long term must remain unclear, as the war has shifted the basic conditions.

The goal of legalizing labor relations, not unconditional confrontation with employers in labor disputes, was a characteristic of the German trade union movement. However, this course was not without controversy. The collective agreement for book printers in 1896 resulted in violent internal conflicts. The opponents saw in this a turning away from the class struggle . Ultimately, the opinion prevailed that collective bargaining agreements would improve the situation of workers without affecting the strike funds, which would preserve the fighting power of the organizations. In 1899 a trade union congress decided that the conclusion of collective agreements would be desirable.

First World War

Outbreak of war

Like the social democratic parties, the free trade unions also professed international solidarity. An international trade union confederation was created . Carl Legien was elected at the top. Like the parties of the Second International , in the July crisis of 1914 the appeals of the trade union international for the preservation of peace were unsuccessful. Instead, the internationality of the labor movement turned out to be an illusion.

The free trade unions signaled their support for the truce as early as August 2, thereby putting the SPD under pressure to act. The parliamentary group in the Reichstag, in which numerous active trade unionists were represented, approved the war credits on August 4th . The general mobilization of the Russian army played an important role in the decision. There was little doubt for those involved that Germany had to be defended against tsarism .

There were other reasons as well. This included the fear of dismantling the organization in the event of refusal. It was also hoped that the state would reward loyalty through concessions. On the right, however, there were also ideas of economic competition that were not dissimilar to the war goals of the government and the right.

The unions did not go on strikes for the duration of the war. Soon there were contacts with various military and civil authorities about nutrition issues, job creation or similar problems. The government relaxed police oversight of the unions and anti-union measures were less rigorous in state-owned companies. The interventions of the state in the economy were interpreted in the trade unions as the beginning of the turning away from capitalism and as a step towards socialism. It was overlooked that there was no clear objective behind this, but rather that it was mostly a reaction to certain predicaments. The hope of encouraging employers to expand the collective bargaining system initially met with limited success. Big industry in particular refused to accept the request. Only in some areas did the military authorities force employers and trade unions to set up war committees to remedy the shortage of skilled workers.

Inner conflicts

In political terms, the leading trade unionists emerged as resolute opponents of Karl Liebknecht's opponents in the SPD. Most of the trade unionists in the SPD parliamentary group belonged to an informal group of the right wing of the parliamentary group. They pleaded for tough action against the critics and consciously accepted the split between faction and party. But not all union members were behind them with this attitude. An appeal by the party opposition in 1915 was also signed by 150 union officials. At the Association Day of the DMV, the board's war course met with open criticism from the delegates. The General Commission stuck to its confrontational course against the left and put the party under pressure by threatening to found a trade union party if necessary.

The General Commission expressly welcomed the end of factional unity in 1916. With Hermann Jäckel from the textile workers' union and Josef Simon from the shoemakers there were also supporters of the opposition in the general commission, but both the opposition and the USPD wanted at least to keep the union unity. They hoped for a gradual strengthening of the opposition in the trade unions themselves. In fact, the opponents of the truce had already achieved a strong position in Berlin, Leipzig, Dresden or Braunschweig . On the Association Day of the DMV in 1917, the board was only just able to hold its own against the opposition. In the following years the position of the opposition in the DMV increased and in 1919 it was able to replace the old board.

Auxiliary Service Act

The unions themselves got into an organizational crisis after the start of the war. The number of members of the free trade unions sank to around the level of 1903 by 1916. The reasons were the drafting into the military, the initially high unemployment in non-war industries, but also the decline in attraction after the strike was abandoned. All of this resulted in a gradual loosening of union control over workers. Criticism of the truce policy of the union leaders also increased among union members. Wild strikes and food riots broke out since 1915 . The problematic war situation caused the Supreme Army Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff to demand a comprehensive program to improve arms production. A major component was the restriction of freedom of movement and the obligation to work.

However, this required the approval of parliament and the trade unions. The unions agreed on a uniform approach and, based on the parties closely related to them, from the SPD to the left wing of the National Liberals, extensive changes were made to the Auxiliary Service Act . The unions agreed to the regulation of the labor market. In addition, workers 'and salaried employees' committees were set up in all war-important factories with more than 50 employees, the members of which were proposed by the trade unions. The chairman of the DMV Alexander Schlicke was appointed to the war office. This was the first time that a free trade unionist held an official position. The state recognition of the trade unions as professional representatives of workers' interests was achieved. Various committees were made up of equal numbers of employee and employer representatives. In factories important to the war effort, union participation was introduced in some areas .

Since then, the unions have also been able to gain a foothold in large companies. The companies saw the law as an exceptional law against employers, while the trade unions celebrated it as a great success in their war policy and a move towards an organized economy . However, the law also meant an even closer identification with the measures of the state and thus a loss of autonomy. As a result, officials and members sometimes drifted further apart. On the face of it, however, the law resulted in a revival of the trade unions. The number of members rose sharply again after 1916 without reaching the pre-war level.

Way to revolution

The increasing hardship on the home front led to increasing dissatisfaction among the workers. Local strikes have become more frequent since 1917. First, 40,000 workers at Krupp in Essen went on strike before the strike spread to the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial area, Berlin and other cities and regions. In January 1918 this affected the armaments industry throughout the entire Reich. The number of strikers in the January strikes exceeded the million mark. In the strikes, political dissatisfaction was combined with social hardship.

The leading minds and organizers came in particular from the core workforce. They had often gained experience in the labor movement as SPD members and trade unionists before the war. The most famous group were the Revolutionary Obleute in Berlin and other cities. These were close to the USPD and council democratic ideas . They developed grassroots and business-oriented forms of industrial action that differed from those of the centralized unions. The chairmen had an influence above all in big cities. However, one should not overestimate the scope of this opposition, as the number of union members increased sharply during this period and was hardly affected by the unrest in other sectors.

Nevertheless, the mass strikes in the arms industry were part of a gradually growing revolutionary mood. Against this background, the trade unions pushed for reforms. They were ready to change their systems, but didn't step too much themselves to help. Gustav Bauer , the second chairman of the free trade unions, joined Max von Baden's cabinet at the beginning of October as head of the new Reich Labor Office . The October reforms appeared to the leaders of the free and Christian trade unionists as a great success and a decisive step towards democracy. They wanted to keep going and prevent a revolution from breaking out. This did not succeed, and neither the MSPD nor the free trade unions initially had any significant influence on the November Revolution . This changed with the formation of the Council of People's Representatives . The free trade unions supported his policy. However, they did not play a significant part in the formation of the new government.

Weimar Republic

November Agreement

Concerns about a revolutionary collapse caused the trade unions and employers to approach one another during the war. The first negotiations for a cooperation failed in early 1918 due to resistance from heavy industry. This only changed in the last weeks of the war. On the business side, concessions to the trade unions were the lesser evil to prevent a possible nationalization of big industry. On November 15, employers and trade unions agreed on the so-called Stinnes Legien or November Agreement . In it, the employers now also recognized the trade unions as the appointed representatives of the employees' interests and guaranteed full freedom of association. Furthermore, the collective agreement system and the establishment of workers' committees in companies with more than 50 employees were approved. Support was withdrawn from the yellow business unions and the eight-hour day with full pay was introduced. Employers and trade unions have created work records with equal representation and arbitration committees have been introduced. The unions had thus pushed through demands for which they had fought for decades. On the basis of the November Agreement, the Central Working Group of Industrial and Commercial Employers and Employees (ZAG) was founded on December 4, 1918 . For the unions, these results were a step towards democratizing the economy. However, the courtesy of employers only proved to be limited to the immediate revolutionary period. In the unions themselves, especially in the DMV, the agreements were heavily criticized. The Nuremberg Congress of Free Trade Unions in mid-1919, however, approved them by a majority. The DMV left the ZAG in October 1919, and unions followed in the following years.

Political policy decisions

On a local basis, trade unionists had, in some cases, played a leading role in the workers and soldiers' councils . A considerable number of the majority Social Democratic delegates at the Reichsrätekongress from December 16 to 21, 1918 were full-time trade unionists. They rejected a council-democratic structure of the state. The unions tried to isolate the radical currents in the council movement. The members of the workers 'and soldiers' councils from their ranks tried to integrate the union leadership into a concept that the councils only wanted to exist until the National Assembly and that they should not have any co-determination rights in the economy.

The election to the German National Assembly did not result in a socialist majority, as had been hoped by the free trade unions. Nonetheless, the trade unions were staunch supporters of the republic . A third of the MSPD MPs in the National Assembly were some high-ranking officials of the free trade unions. With Gustav Bauer, Robert Schmidt and Rudolf Wissell , three leading trade unionists were members of the Scheidemann cabinet . For some time Bauer succeeded Scheidemann as head of government. There were also prominent trade unionists in the following cabinets. It was similar in the countries. The chairman of the woodworkers' association Theodor Leipart became the Württemberg labor minister.

Non-parliamentary concepts such as council democracy continued to be rejected by a majority of the unions. Nonetheless, there were supporters within the trade unionists as well. At the first post-war congress of the free trade unions in Nuremberg in the summer of 1919, Richard Müller presented a detailed political council concept, which was rejected by the majority. At the top of the union there were conflicts between a wing of the traditionalists over Legien and reformers over Leipart. In this dispute, with the support of the SPD, the reformers prevailed, who advocated the creation of works councils . With this, the free trade unions gave up their complete rejection of the councils and in part moved away from the previous location-based organization of the labor movement in favor of the company level.

In economic terms, many workers have called for the socialization of various industries as a step towards socialism. The leadership of the trade unions were skeptical of this. In parts of their own supporters this was seen differently. In the Ruhr area, for example, there was a broad socialization movement . The unions maintained their negative stance on this matter, also because it could not be brought into line with the course set in the November agreement.

Instead, Rudolf Wissell promoted the concept of the common economy . The economy should be operated according to plan and socially controlled. The means of production should remain in private ownership. It should not serve the profit interests of individuals, but the common good . Neither public economy nor socialization could be enforced, also because the respective supporters blocked each other.

In the early days of the Weimar Republic, important decisions were made that corresponded to union demands and goals. Collective agreements were declared legally and generally binding, regulations for hiring and firing employees were made and the eight-hour day was introduced. Central points were even written into the constitution . The Works Council Act of 1920 was also important. However, this was not without controversy in the trade unions, since it did not go far enough, especially for the proponents of a political council system.

Inner development

Membership development

The number of union members continued to grow after the revolution. In the first quarter of 1919 the number of members in the free trade unions skyrocketed by 1.81 million to 4.67 million. Overall, the number of members also subsequently increased before a setback set in in connection with inflation .

The number of members rose particularly sharply in sectors that were previously barely organized. These were the state workers, railroad workers, farm workers and similar groups. The same applies to large companies. The unions were also able to advance into new regions. This applied to eastern German agricultural areas or the Saar area, where before the war the employers had severely obstructed the unions. In parts of the Ruhr area and neighboring areas in particular, the Christian trade unions were sometimes stronger than the free organizations.

The structure of the members also changed. The numerical importance of the skilled craftsmen in small and medium-sized enterprises decreased in favor of the less qualified factory workers in large enterprises. The proportion of women also increased significantly. In 1918 it was 25%, but then fell slightly to 20% by 1924. Overall, the ADGB lost almost 50% of its members by 1924, compared to 1920.

The drastic decline in membership during the inflationary period continued even further in 1924, which was marked by austerity measures. In 1925 the numbers stagnated, only to plummet in 1926. The low point was only reached this year. The ADGB still had 3.9 million members at that time.

In the following years until 1930 the number of members increased again. But they never reached the level of the early 1920s. With regard to workers' organizations, the ADGB clearly remained the dominant association. It looked different with the employee organizations. The stagnating free trade union AfA-Bund was overtaken by the Christian-national associations. The General German Civil Service Association also lagged behind the DBB .

As a result of the global economic crisis , the number of members, especially in the workers' unions, has again fallen sharply since 1930. The decline was less pronounced for white-collar unions. The trend towards the more nationally oriented associations to the detriment of the AfA Federal continued. Overall, the ADGB associations lost more than a quarter of their members between 1929 and 1932. In some associations, such as those of machinists or clothing workers, the loss was even over 40%. Other associations also lost above average. These included the building trade union, the factory workers, the tobacco workers and the textile workers.

Restructuring

| Surname | Number of members |

|---|---|

| Building trade association | 435.156 |

| Garment workers | 77,884 |

| Miners | 196.049 |

| Bookbinder | 55,128 |

| Book printer | 82,767 |

| roofer | 10,843 |

| railwayman | 240.913 |

| Factory workers | 457.657 |

| Firefighters | 7740 |

| Film union | 1300 |

| Barber assistants | 4057 |

| gardener | 10,518 |

| Community and state workers | 243,968 |

| Graphic laborers | 40,691 |

| Woodworker | 306.660 |

| Hotel, restaurant and cafe employees | 27,153 |

| Hat worker | 18,509 |

| Coppersmiths | 7024 |

| Farm workers | 151.273 |

| Leather workers | 37,855 |

| Lithographers and lithographers | 23,719 |

| painter | 58,775 |

| Machinists and stokers | 48,568 |

| Metalworker | 884.027 |

| Musician | 23,055 |

| Food and beverage workers | 159,636 |

| Saddler, upholsterer ... | 30,614 |

| chimney sweeper | 2980 |

| Shoemaker | 78,834 |

| Swiss | 11,456 |

| Stone workers | 68.033 |

| Tobacco workers | 75.501 |

| Textile workers | 306.137 |

| Transport Association | 368.052 |

| Carpenter | 107.354 |

At the first post-war congress of the free trade unions in Nuremberg in 1919, 52 associations were represented, representing 4.8 million members. Although the debate was controversial, the Assembly had retrospectively approved the course of the General Commission on War and Revolution. In addition, other current issues were discussed, some of which have already been addressed. At the congress there was also a reorientation in terms of content and organization. The unions declared themselves to be politically neutral. This was also necessary because there was no longer any unified political workers' movement. This, too, has contributed to the fact that there was no split within the trade unions despite all the internal differences between the supporters of the SPD, USPD and KPD .

The ADGB was founded as a new umbrella organization at the first post-war congress of the free trade unions. The previous general commission was replaced by a board of fifteen members. Carl Legien became chairman. After his death in 1921 Theodor Leipart became chairman. The highest body of the ADGB was the federal congress, which meets every three years. At the local level there were local committees of the ADGB, they replaced the previous local cartels . They brought together the local paying offices of the free trade unions. There have been district committees on this since 1922. The individual trade unions were structured similarly.

At the beginning of the 1930s there were around 6,000 full-time functionaries, the vast majority of whom worked in the local administrations of the individual trade unions. The apparatus at the ADGB board consisted of only about 40 people.

At the trade union congress in Essen in 1922, the industrial association principle was given as a goal. The trend also slowly went in this direction and the number of individual associations fell slightly. The General Free Employees' Association (AfA), founded in 1920, and the General German Civil Service Association, founded in 1922, concluded cooperation agreements with the ADGB in 1923.

By changing the association legislation, the unions organized more youth and women. Organizational work has been strengthened for both groups. Gertrud Hanna was a key figure in the field of women's work .

In addition, general educational work was strengthened. The free trade union seminar was founded there in connection with the University of Cologne . In Frankfurt originated Academy of Labor , in Berlin the technical colleges of business administration were founded, where the trade unions were involved. In 1930 a federal school of the ADGB was founded in Bernau . The theoretical organ Die Arbeit was published in 1924 .

Union opposition

A characteristic of the situation in the post-war period was that there was quite a strong opposition within the union that rejected the course of the board. This was particularly well represented in the DMV. 64 of 118 delegates of the DMV at the first post-war congress of the ADGB are to be assigned to the opposition. There was no split, but the opposition was gaining ground in the free trade unions. In the DMV, the opposition had a majority at the 1919 general assembly and, with Alwin Brandes and Robert Dißmann, two members of the board of directors, while Georg Reichel represented the previous majority. The opposition also had a majority in the associations of textile workers and shoemakers. She was an important factor in a number of other associations. Among other things, the different generational experiences of the long-serving functionaries and the numerous new members contributed to this.

Many internal conflicts also reflected the division of the labor movement into MSPD and USPD or KPD. This party changed its union course several times. Initially, it relied on the formation of cells in the free trade unions. In autumn 1919 the party issued the slogan: “Get out of the trade unions!” Some of those who were dissatisfied with the majority course found themselves outside the free trade unions in their own, often syndicalist, associations. These were, for example, the General Workers' Union , the Free Workers' Union of Germany , the Communist-influenced Free Workers' Union (towards Gelsenkirchen) and, since 1921, the Union of manual and mental workers . This association dissolved in 1925 at the urging of the KPD, and the members rejoined the free trade unions. At times, these rival associations had a considerable following, especially in large companies in the Ruhr area and in central Germany. After 1923/24, however, they lost their importance. In 1929 the Communist Revolutionary Trade Union Opposition arose .

Development until the end of inflation

Kapp putsch

The trade unions played a decisive role in ending the Kapp Putsch . The right-wing putsch put the republic in grave danger, especially since the Reichswehr refused to take action against the rebels. On March 13, 1920, ADGB and AfA-Bund called for a general strike. This was supported in the following days by the KPD, the Christian trade unions and the German Association of Officials. After all, 12 million workers were on strike. Not least the general strike contributed to the fact that the putschists had to give up on March 17th.

The trade unions initially continued the strike and raised demands for the dismissal of incriminated people like Gustav Noske or Wolfgang Heine and for the democratization of the administration. Overall, they hoped for a general reorganization of politics and, on the economic level, the socialization of the economy. When the new cabinets were formed in the Reich and Prussia, representatives of the trade unions in particular were to be taken into account, and one dreamed of a pure workers' government. The government made certain non-binding commitments. After Noske's resignation, the general strike ended on March 22nd. The negotiations to form a workers' government failed not only because of resistance from the center and the DDP . The USPD refused to sit in a cabinet with “worker murderers” and Legien was reluctant to take on the post of Chancellor. Finally, a cabinet was formed under Hermann Müller . The various commitments to the unions, including socialization, were not implemented.

In the Ruhr area, riots and the formation of a Red Ruhr Army had already begun during the general strike. Carl Severing in particular reached an agreement with the rebels in the Bielefeld Agreement . But when the Müller government refused to recognize this and threatened violence, the strike was resumed. Against the will of ADGB, depreciation covenant SPD and USPD the Army marched into the Ruhr area and struck the Ruhr uprising bloodily. The political influence of the trade unions continued to decline when a bourgeois government under Constantin Fehrenbach was formed after the Reichstag elections of 1920 .

Ruhr occupation

The crisis year 1923 began with the occupation of the Ruhr by French and Belgian troops. The area was intended as a productive pledge for the German reparation obligations . The free trade unions immediately condemned the move as an act of violence. They joined the call of the government under Wilhelm Cuno for passive resistance. Funding the Resistance greatly fueled inflation.

Against this background, too, the trade unions were increasingly skeptical of the resistance. The positions of the government, which wanted to hold on to the resistance, and the free trade unions, which were pushing for an agreement with the occupiers, diverged. The unions urged the government to open negotiations on April 21, but to no avail. In the end, the government submitted proposals for resolving the reparations problem, but the French rejected them. On May 9th, the unions backed the government demonstratively. Although it became increasingly clear that the resistance was making less and less sense, out of consideration for the government, the unions avoided proclaiming an end. During this period, union pronouncements were not always devoid of nationalistic undertones.

Union work and inflation

Inflation Consensus and Wage Policy

In the early 1920s, trade union work in the narrower sense was increasingly characterized by increasing monetary devaluation. Initially, this had advantages for both companies and employees. Inflation made the German economy more competitive internationally, revitalized the economy and had positive effects on the labor market. In contrast to other countries, Germany was spared a post-war depression.

This was one aspect that led to an informal inflationary consensus among employers and unions, neither of which had any real interest in currency stabilization. Nevertheless, wages had to be adjusted to the ever increasing price increases. The consumers had to bear the costs, which in turn led to new wage demands. However, it became more and more difficult to compensate for the rising cost of living in wage negotiations. Wage negotiations became necessary at ever shorter intervals. In 1922 these took place weekly. After all, in 1923 wages could only be adjusted to rising inflation by means of a cost of living index. The real wages declined from the prior 1900-1923 to 60%. The unions did not have a viable stabilization strategy. In particular, they demanded the taxation of material assets, profit skimming, the strengthening of mass purchasing power and an active job creation policy after unemployment had risen sharply. However, the proposals were not well thought out and not very suitable to solve the basic problem of inflation. The labor disputes of the early 1920s often ended in defeat and the results were in any case outdated after a short time.

Fight for the eight-hour day

In addition to wage policy, the question of working hours played a central role. In the Ruhr area there had been massive efforts, including strikes, since the end of 1918 to achieve a six-hour shift. In 1919/20 this was combined with demands for socialization. Ultimately, these attempts failed. With a view to the reparations demands in 1920, the trade unions also agreed to a shift agreement in the coal and steel industry that allowed working hours to be extended. This was seen as a success by employers. Dissatisfaction with the trade unions' concessions increased the number of syndicalist organizations. In southern Germany, too, efforts were made to achieve shorter working hours than those agreed at the end of 1918. There were lockouts there by employers in 1922. The conflict ended in the defeat of the unions.

The eight-hour day agreed in 1918 was increasingly questioned by employers. The question had to be resolved politically because the previous regulation was based only on a demobilization ordinance. The dispute over working hours contributed significantly to the resignation of Gustav Stresemann's cabinet on October 3, 1923. After the SPD left the government on November 3rd, a working time ordinance made it possible to extend working hours. The government reacted to pressure from the Ruhr industry. The trade unions, which until then had been able to prevent all attempts to extend working hours, did not see themselves strong enough to offer vigorous resistance against the background of high unemployment and the wave of withdrawals in the organizations. At the end of 1923, the unions had reached their lowest point of post-war development in terms of membership development and their influence. On January 16, 1924, the ADGB resigned from the meanwhile meaningless central working group with employers.

Weakening of the unions

After the formation of bourgeois governments, the trade unions also lacked partners in politics. In many areas of social and economic policy, the trade unions were unable to penetrate with their ideas. In 1923, the regulation of the arbitration system restricted collective bargaining autonomy. If the employer and employee did not reach an agreement, the Reich Labor Ministry could, if necessary, declare a previously issued arbitration award to be binding against both parties. The unions criticized this, but especially in their weak phase between 1924 and 1926, they had to make use of the arbitration bodies because otherwise they would have had no chance at all against the employers' side. Even when the situation of the trade unions had improved again, they did not seek any fundamental changes.

Not least because of disappointment with the poor social situation and the unsuccessful representation of interests, there were massive withdrawals from the unions. The financial situation of the organizations was severely burdened by the devaluation of the invested financial assets and the falling membership fees. Services had to be canceled, officials were dismissed and newspapers were discontinued.

Relative stabilization phase

Organizational recovery and union business

After the slump at the end of the inflationary period, it was not only the membership of the trade unions that gradually increased again. The organizational structures also recovered. A number of district secretariats, which were closed due to the crisis, were filled again. Overall, the administration was expanded. The number of member associations continued to decline. But there was no clear implementation of the industrial association system.

The phase between inflation and the global economic crisis was the heyday of the cultural, social and educational activities of the trade unions. Numerous training facilities, legal information centers (workers' secretariats) and libraries have been set up. The smaller, financially weak associations in particular urged the development of central institutions of the ADGB.

Press work was also intensified and the publications made more public. But new papers were also founded. With the journal Die Arbeit, a theoretical organ was created. Together with the SPD, the Research Center for Economic Policy was founded in 1925 under the direction of Fritz Naphtali . With the gradual decline of the intra-union opposition, general relations with the SPD were also strengthened. However, the implementation of a plan for corporate membership of the free trade unions in the SPD did not materialize.

In the second half of the 1920s the public service enterprises flourished. This was partly done by the trade unions. They participated in others. Economic activities took place within the framework of the capitalist system. The bank of workers, employees and civil servants was founded in 1923/24. It experienced an enormous boom in the following years. Public-sector construction companies joined forces to form the Association of Social Construction Companies . Deutsche Wohnungsfürsorge AG , Volksfürsorge , various consumer cooperatives and publishers were also successful .

Economic situation and wage policy