Lothar Erdmann

Karl Hermann Dietrich Lothar Erdmann (born October 12, 1888 in Breslau , † September 18, 1939 in Sachsenhausen concentration camp ) was a German journalist. During the Weimar Republic he was the editor of the trade union theory organ Die Arbeit . He was a major advocate of the trade unions' turning away from social democracy at the end of the republic. Despite the rapprochement with National Socialism , he died after being mistreated in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Early years

The father was the philosopher Benno Erdmann . After his father was called to the University of Bonn, Lothar Erdmann attended the local high school there. He later studied history and philosophy . He was a student of Friedrich Meinecke . Erdmann met George Bernard Shaw in England . Through this he came into contact with the Fabian Society . From this in turn he came to socialism . Now he no longer aspired to an academic career, but wanted to become a journalist.

Before he could establish himself in this industry, the First World War broke out. Erdmann registered as a volunteer and was deployed on the Western Front. Here he was company commander and rose to lieutenant. The death of his friend August Macke hit him hard and this contributed to the fact that his attitude towards the war changed. A severe nervous breakdown ended the front line in 1916. Instead he was posted to Wolff's telegraph office. Erdmann worked for this in Amsterdam as a translator. In 1916 he married Elisabeth Macke , née Gerhardt, the widow of his friend August Macke. From this marriage there were three children: Dietrich , Constanze and Klaus.

During this stay he got in touch with leading representatives of the international trade union movement . He was very moderate and opposed radical union ideas. His concept of socialism was associated with a strong concept of nation.

Weimar Republic

After the end of the war, Erdmann returned to Germany. There he became a member of the SPD . He worked in Cologne as an editor for the Rheinische Zeitung. As a friend of Mackes, Erdmann also arranged his artistic estate. One of the first larger works on Macke was also created. It appeared in 1928 in an anthology edited by Ernst Jünger with the title Die Unvergessenen .

Erdmann returned to Amsterdam after some time in Germany and worked as press officer for the International Trade Union Confederation. Back in Germany, Erdmann founded the magazine Die Arbeit in 1924 . This was the theoretical sheet of the ADGB . On his behalf, he performed the function of a union secretary for the Berlin area. Erdmann remained editor-in-chief of the new magazine until 1933, with which he was able to exert considerable influence on the attitude of the union leadership to current issues. Erdmann was also a close employee of the union leader Theodor Leipart . Before the Reichstag election of 1930 , Erdmann said that it was not the National Socialists with their (supposedly) smaller supporters, but the DVP and DNVP , who could possibly enter into an alliance with the NSDAP , that would be a threat to “democratic socialism”.

In 1932 Erdmann tried to get Kurt von Schleicher to support the unions. Erdmann, who also worked as a speechwriter for Leipart, found ideas from Ernst Jünger's work Der Arbeiter. Dominance and shape Entrance into the union environment.

Approach to the Nazi regime

In the last edition of his paper of April 29, 1933, Erdmann's contribution Nation, Unions and Socialism appeared , which Heinrich August Winkler assumes was essentially agreed with Leipart. In this article, Erdmann distanced himself from the SPD in a hitherto unknown severity and emphasized the essential differences with the trade unions. According to this, the Marxism of the trade unions was never a belief in an all-inclusive theory. “ We are socialists because we are Germans. And that is precisely why the goal for us is not socialism, but socialist Germany. (...) German socialism grows out of German history into the future living space of the German people. Socialist Germany will never become a reality without the nationalization of the socialist movement. “For Erdmann, National Socialism was a logical consequence of the Versailles Treaty and the inability of the SPD to transform itself into a national party. He ended his contribution with an appeal to the National Socialists to integrate the trade unions into the new state. “ The national organization of work that they have built up over decades of hard struggles and immeasurable work, supported by the trust and willingness to sacrifice of the German workers, is a national value that the allied forces of the national revolution must also respect and guard above all the great movement that claims that its revolution is national and socialist at the same time. (...) They [the trade unions] need, even if they have to give up some things that corresponded to their historical nature, not to change their motto 'Through socialism to the nation' if the national revolution follows their will to socialism with socialist deeds. "

Erdmann was not alone with these theses. Other younger ADGB functionaries at the middle level also shared his positions, for example Walter Pahl .

Last years and death in the concentration camp

The goal of ensuring the survival of the trade unions by largely adapting to the regime was unsuccessful. When the union houses were occupied on May 2, 1933 , Erdmann lost his job. He then worked as a writer and freelance journalist. However, he was only able to publish in a few newspapers and magazines. He mainly wrote reviews of books and visual artists.

At the beginning of the Second World War he was arrested as part of the special war campaign . Erdmann was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp . There he protested the mistreatment of a fellow inmate upon arrival. He was then forced to do a punishment exercise, which was extended by an hour every day. After six days he collapsed in what was construed as mutiny . This was followed by three hours of “hanging on the pole” as well as numerous blows and kicks. Eventually he died of enormous internal injuries.

His estate is in the archive of social democracy .

Honor and memory

In 1960, the GDR Post published a series of portraits of anti-fascists murdered in the concentration camp. The 5 pfennig value shows the portrait of Lothar Erdmann.

In the ring wall of the Socialist Memorial at the Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery , Dr. Lothar Erdmann remembers.

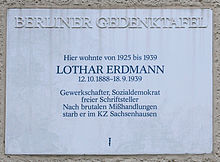

At his house in Berlin-Tempelhof who let the Senate of Berlin , a Berlin Memorial Plaque attach.

In 2003, the Sachsenhausen memorial mainly honored former active union officials whose fate is little known.

In 2004 Ilse Fischer published a biographical study about Erdmann, which also contains his diary entries.

Web links

- Biography of the Archives of Social Democracy

- Short biography of the DGB

- Literature by and about Lothar Erdmann in the catalog of the German National Library

literature

- Ilse Fischer: Reconciliation of Nation and Socialism? Lothar Erdmann (1888–1939): A “passionate individualist” at the top of the union. Biography and excerpts from the diaries ( AfS , supplement 23), Verlag JHW Dietz Nachf., Bonn 2004, ISBN 3-8012-4136-X .

- 10 years of the Sassenbach Society (including Axel Bowe: a difficult birth , Helga Grebing : a successful experiment , Hans Otto Hemmer: a current interview with contemporary witnesses - Dietrich Erdmann about his father Lothar Erdmann ). Issue 4, Berlin 2001.

- Social Democratic Party of Germany (ed.): Committed to freedom. Memorial book of the German social democracy in the 20th century . Marburg, 2000 p. 90.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Anti-fascists murdered in Sachsenhausen. Maximum postcards , issued by the Board of Trustees for the Development of National Memorials in Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen and Ravensbrück. Berlin 1960

- ↑ See Erdmann-Macke, Elisabeth at www.bonner-stadtlexikon.de.

- ↑ Michael Schneider: Ups, Crises, Downs. The unions in the Weimar Republic. In: Klaus Tenfelde u. a .: History of the German trade unions from the beginning until 1945 . Cologne, 1987. p. 423

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The way into the disaster. Workers and labor movement in the Weimar Republic 1930 to 1933 , Verlag Dietz JHW Nachf., Bonn 1990, ISBN 3-8012-0095-7 , p. 720

- ↑ Winkler: Weg in die Katastrophe ... , p. 747

- ↑ Winkler: Weg in die Katastrophe ..., p. 895

- ↑ cit. according to Winkler: way into the disaster ... , p. 894f.

- ↑ cit. According to Winkler: Path to Disaster ... , p. 895

- ↑ Information about the memorial of the socialists at the ZF Friedrichsfelde ( memento of July 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on December 24, 2011

- ↑ Trade unionists in the resistance against National Socialism: Honor in Sachsenhausen . From migration.online , accessed December 24, 2011

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Erdmann, Lothar |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German journalist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 12, 1888 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wroclaw |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 18, 1939 |

| Place of death | Sachsenhausen concentration camp |