National Socialist Christmas Cult

The National Socialist Christmas cult had the goal of expanding the effectiveness of the ideology of National Socialism on German Christmas customs ( German Christmas ). By Nazi propaganda of the influence that was to Christian faith to the national community had to be pushed back. According to the psychologist Wilfried Daim , instead of Jesus Christ, Adolf Hitler should take on the role of Messiah and World Savior. The National Socialist Christmas cult combined patriotic , “ youthful ” and folk Christmas mysticism, symbolism supposedly borrowed from Germanic mythology , exaggerated glorification of mothers and heroes .

The Germanized interpretation of Christmas was at the beginning particularly in the interest of Germanophile circles within the protection squadron of the NSDAP, the Rosenberg office and folklore . In the pre-war period, the Propaganda Ministry influenced Christmas through the Winter Relief Organization of the German People . It was staged in front of the population as a "festival of the whole people [...] across classes, ranks and denominations". During the Second World War , the National Socialist leadership appropriated Christmas for war propaganda . The dispatch of field post parcels , the production and broadcasting of so-called Christmas ring consignments on the radio, as well as the organization of Christmas as a festival of worshiping heroes and dead were an integral part of these years.

Despite all efforts, it was not possible in large parts of the population to suppress the traditional Christian Christmas festival.

Christmas and the interpretation under National Socialism

The worship of the sun and the returning light in the end of December goes back to traditions in prehistoric times . The seasonal turning points ( solstice ) were reflected accordingly in rite and mythology . The sun was essential for earthly survival. The summer solstice had an aspect of death and impermanence in it. This contrasted with the lengthening days after the winter solstice, which embodied life and resurrection. However, it is debatable how large the role of the solstice was in Norse and late Germanic pre-Christian mythology. It is noteworthy that in the " occidental " culture the male principle was assigned to the sun, but here there is an exception in the Germanic language area, which assigns the sun to the female origin. The Germans are the Yule celebrated the winter solstice with fire and light symbolism. Historically verifiable written evidence is only known to a few, mostly in the form of calendar sticks with runic symbols .

For a long time the Christian Christmas festival ("the birth of the true sun" Jesus Christ) was considered to be an overprint of the Roman-pagan imperial cult and the cult in honor of the god Sol . The fact that Emperor Aurelian declared December 25th in the third century to be an empire-wide “dies natalis solis invictis” is controversial in the latest research. Today one assumes a parallel development. The day of the winter solstice was probably occupied first by the Christians, as there was no pagan solemn festival on this date. The first reliable mention of the pagan festival “Sol invictus” in the city of Rome can be traced back to the year 354. Furius Dionysius Filocalus described in the chronograph of 354 this December 25th as the date of the birth of Jesus Christ. The development of the festivals in honor of the respective god had the same Neoplatonic- solar mythological roots and they were in close exchange. Both sides associated with the "newly emerging sun" at the winter solstice.

In the early Middle Ages, Christian missionaries adapted Germanic customs and rituals such as the tree of lights at the winter solstice. They did not do this because of their fascination with Germanic customs. They believed that the goal of proselytizing, Christianization, would be easier to achieve if the customs of the population were incorporated into their religion. In the German-speaking world, Christmas was mentioned for the first time at the "Bavarian Synod " and introduced in 813 at the Mainz Synod.

During the Nazi era , the Nazi ideologues tried to push back this Christian diction of Christmas. The German Ahnenerbe Research Foundation and the Rosenberg Office looked for historical and archaeological evidence for the interpretation of Germanic rites and myths. A National Socialist “substitute religion” should be the goal of all ideological work. However, there is no agreement on this point of view. Christian cult forms and rituals were adopted into the outward form of the National Socialist celebrations. The experience "that made the heart beat faster" should win the average national. Therefore, the design of the celebration was very important for the formation of the National Socialist state.

With the penetration of everyday life with new celebrations, symbols and myths and with the reinterpretation of the religious festivities anchored in the population, the National Socialist party designers aimed to convey National Socialist ideas and values through an emotional bond. Hitler's leading ideologue, Alfred Rosenberg , allowed borrowings from the Germanic sun cult to flow into the celebrations, and incorporated occult and theosophical elements into the newly developed folk culture and its customs. In order to link this new faith with Christian traditions, Rosenberg made use of a consciously introduced National Socialist language that was based on the sacred language of the church. This language took up elements of the church liturgy . For example, the so-called “National Socialist Creed” and the “Sieg Heil!” ( Hitler salute ) were spread as a reference to the “ Amen !” Customary in liturgical celebrations .

According to the National Socialists, Christmas was "stolen" from the Germans by the Christians and the Jews. In publications one derived, historically not verifiable, Christmas from the Germanic Yule Festival. An attempt was made to separate the "alleged mixture". This deliberate “rule-Germanization” was not supported by all party members.

Christmas between secularization and sacralization

The youth movement of the 1920s preceded the new secularization in the relationship between state and churches in Germany. This often covenant youth celebrated solstices and lit large fires in places that could be seen from afar. The Christian Christmas festival played a role for the National Socialists, who promoted sacralization in their own ideology. This festival was now to be celebrated as the winter solstice and “confession ceremony for the people and leaders”.

The National Socialist rulers were mostly critical and hostile to religious convictions. But only Rosenberg, as the only Nazi politician in the first guard , left the church on November 15, 1933, after the takeover of power . The power of the church could not be ignored because the Christian faith was firmly anchored in large parts of the population. The proportion of members of Christian churches during the Nazi era, i.e. the number of members of the two Christian denominations, was almost 95 percent at the beginning and at the end. In the 1939 census , around 3.5 percent of the remaining 5 percent described themselves as “ believers in God ” and around 1.5 percent believed they were unbelieving. The remaining group of around 0.1 percent (86,423 people) included people who were “members of a church, religious society or religious and ideological community”. This also included the “German-Believing Movement”. The introduction of the term "believing in God" in 1936 was an attempt by National Socialism to create a religious identification formula for National Socialists beyond the churches and other religious communities.

Hitler in particular had a split relationship with the church. He had no clear ideas about a future German religion. He took the position that it was best to slowly let Christianity fade away. At the same time he was aware that if he were to remove the church by force, the people would cry out for a replacement. According to those in power, the place of the churches should in future be taken by the “German national community”. But those who claimed ideological participation and wanted to shape the “German religion” argued without a “fraternal tone”. They were Hitler's Faithful Rosenberg, Heinrich Himmler , Joseph Goebbels , Bernhard Rust , Baldur von Schirach and other party comrades.

Exaggeration of Hitler

As early as 1930, after obtaining government participation in Thuringia , the National Socialists tried to reorganize the school system. According to the law of April 16, 1930, regular prayers should be held in schools in their favor. Later, in the media and in child and youth work, the image of Adolf Hitler was increasingly built up as a “God-sent” and “God-willed” Messiah who, with “God's help”, rose to become the leader of the German nation. The population now explicitly included Hitler in their prayers and intercessions . Rudolf Hess , Hitler's deputy, said in 1934: “We cannot end this hour of the community of Germans in the world other than to devote our remembrance to the man whom fate has determined, the creator of a new German people be - a people of honor. The gift that we Germans bring to the world Adolf Hitler again for Christmas is: trust. We place our fate in his hands anew as a thank you and a vow at the same time. "

Christmas played an important role in exaggerating Adolf Hitler. Government agencies were involved. For example, at Christmas 1937, the Reichspost stamped postage stamps with the inscription: “Our Leader the Savior is here!” Based on “Christ the Savior is here!”.

German Christmas from 1933 to 1945

In order to establish festive customs such as the National Socialist Christmas party, the "Office of the Führer Commissioner for the Supervision of the entire spiritual and ideological education of the NSDAP" (Rosenberg Office) was created after the takeover of power . The "Center for Celebration and Celebration Design" coordinated the propaganda of various organizations and offices. One of the most urgent tasks of the "National Socialist party designers" was the gradual suppression of the Christian character of Christmas. Instead, the “festival of the people's community under the tree of lights” - the German Christmas - should take place as the victory celebration of the “national rebirth”. Between Rosenberg and Reich Propaganda Leader Joseph Goebbels there were disputes over the ideological objectives of the reorganization of Christmas until 1942. Rosenberg wanted to create a new myth as a replacement for Christian beliefs, namely that of the "Germanic-German religious renewal".

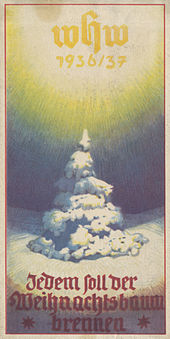

The Christmas collections of the Winter Relief Organization (WHW)

In view of the global economic crisis at the beginning of the 1930s, the then government under Chancellor Heinrich Brüning saw itself prompted for the first time in the winter of 1931 to carry out a nationwide collection campaign to alleviate the emergencies among the population. The National Socialist leadership recognized the potential of this collection campaign for propaganda purposes early on. As early as 1933, the Winter Relief Organization was subordinated to the Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, headed by Joseph Goebbels . It was later organized by the National Socialist People's Welfare . The campaigns with their house and street collections appealed to “solidarity with those in need”. Those responsible tried hard for the Christian population to donate in charity . The constantly changing motifs on door plaques and badges that were worn on clothing or on the outside of the apartment door exerted psychological pressure on those who tried to evade the collection campaign. They gave information about everyone's willingness to donate. At the same time, the badge series also appealed to the passion for collecting. The WHW included children in particular in the collection campaign. In addition, postage stamps were issued by the Reichspost based on the Winter Relief Organization, which were intended to appeal to philatelists . In addition, there was various other income from specially organized sports competitions, "victim shooting", theater events, concerts and collection boxes in shops. The Hitler Youth and the Association of German Girls helped organize the actions. This encouraged young people to take part in the street gatherings shortly before Christmas.

Particularly needy regions in Germany made Christmas badges for the winter relief organization. For example, wooden figures were made for the Christmas tree in the Ore Mountains . Glassblowers in Gablonz on the Neisse and Lauscha in Thuringia made glass jewelry, glass badges and glass figurines for the festival. Initially, most of the motifs of the badges were borrowed from nature, homeland and customs, later motifs with runes, standards and branches of arms were added.

The winter charity collection campaigns took place from October to March. The media participated through wide coverage. Most prominent artists supported the collections with publicity. The winter relief organization was also important during the war, when the soldiers were given warm clothing through the “wool collection”.

The German Christmas from 1933 until the outbreak of the Second World War

Immediately after the takeover of power, over 30,000 celebrations for the National Socialist Christmas with gifts and meals for needy citizens took place in public places. From 1934 these events were moved to large halls. The public Christmas celebrations for “needy national comrades ” were organized by the Reich Labor Service , the Wehrmacht , the National Socialist Women's Association and the Winter Relief Organization. The aim was to establish the German People 's Christmas and thus to promote a positive attitude towards the National Socialist mass organizations. The National Socialist People's Welfare gave out wish lists to the needy at Christmas . Almost exclusively private donors supported several million needy and large families at Christmas. The Deutsches Frauenwerk and other National Socialist women's and youth organizations held meetings in the run-up to Christmas until 1938. The participants "tinkering" and sent Christmas gifts for fellow in the eastern provinces and the Saarland .

In the first few years, the National Socialist regime tried to limit the use of Christian symbols in public. By ordinances and official guidelines - as in 1936 in the context of shop window advertising - a displacement was to be achieved. However, due to the irritation in the population, the rulers relativized or revised such measures after just a few weeks. After the ban on Christian symbolism had failed, people increasingly began to derive Christian traditions and symbols from Germanic customs. The propaganda openly accused the church of manipulating Christmas for its own ends. In pamphlets such as “German Christmas”, “German War Christmas” or in the calendar “Pre-Christmas”, texts refer to the degeneration of the originally Germanic festival of light, an alleged “degeneration through Christianity”.

“When we were children, we experienced it as a festival of giving love, and we heard legends from distant Jewish lands, which seemed strange to us, shimmered with strange magic, but remained deeply alien and incomprehensible to us. Seekers of light were our ancestors who peered into the darkness to perceive the saving message of light. Our Christmas! Certainly there is a hereditary memory of our race, out of which the passionate longings of our ancestors come alive and present in us again. [...] So from time immemorial, Christmas was the celebration of jubilant defiance against the cold and deadly icy winter night. The solstice brought the victory of light! […] This certainty was conveyed by our ancestors and not by astrological kings from the 'Orient'! […] May the others listen in exuberant and confused 'feelings' to 'messages' far removed from life, we proclaim to the world the demands of the law under which we have stood […] freedom on earth! "

After a National Socialist Christmas cult had emerged in the first years of National Socialism from elements of the patriotic and alliance youth movement and folk Christmas mysticism, the outbreak of the Second World War marked a turning point in the propagandistic use of the Christmas festival.

War Christmas

During the war Christmas 1939 to 1944, the "National Socialist party designers" tried to emphasize the bond between soldiers from various front lines and homeland. Fearing that the population would seek consolation in religious faith in times of war, the National Socialist leadership tried to influence the family's Christmas party. The mood was often depressed due to the long separation of members of many families and the loss of family members. New rituals were brought into being, e.g. B. the "memorial of the dead" within the family Christmas party. Some of the Christmas rites introduced up to then were adapted to the war situation. Others, like the winter solstice, were left out entirely. During the last years of the war, propaganda stylized Christmas as a cultic festival of veneration for the dead. This is illustrated in the text of the book “German War Christmas”, which was printed millions of times in 1943. At the same time, propaganda used Christmas to demonstrate the supposed superiority of German culture.

“War Christmas! Right now we recognize the ultimate values of our race, which in the jubilant and defiant rebellion against the darkness against the compulsion, against every unworthy condition, rises to a liberating act. "

Christmas at home

Due to the labor shortage as a result of the men being called up for military service, the women often bore the entire responsibility. In the last years of the war in particular, the procurement of food was disastrous. Therefore, the families improvised in order to still be able to have a “successful” Christmas party. In the first years of the war, the supply situation for the German population was satisfactory, despite the introduction of food cards , Reich clothing cards and vouchers. This is attributed to a systematic looting of the occupied territories. From 1941, the supply situation in the Reich became increasingly critical. Taking advantage of the emotional mood of the Christmas season, the Reich Ministry of Propaganda launched a call for donations of wool, fur and winter items a few days before Christmas. In the final years of the war, food stamps were saved for weeks in order to be able to exchange them for food in special Christmas rations. Everyday objects that are often used for Christmas - such as candles - were made from leftover wax by young people and women in joint craft evenings.

As a result of the numerous air raids, the destruction of the residential buildings, the evacuations and the war-related deaths, it was hardly possible to celebrate a peaceful Christmas. Resignation and sarcasm overwhelmed the population. In the last years of the war, families often spent a lot of time in air raid shelters due to the almost daily overflights of Allied bomber squadrons . The population also increasingly spent Christmas Eve in the bunker.

On the part of the National Socialist propaganda, the “German mother” was staged as the counterpart to the “German war hero”.

Christmas at the front

The staging of Christmas days at the front was given special attention by the propaganda companies of the individual units. Elaborately designed photo and film reports in the Deutsche Wochenschau, the Frontschau and the monthly picture reports of the NSDAP should convey a harmonious picture of the Christmas celebrations at the front, as perfectly staged as possible. In all reports, the Christmas tree was effectively staged as the German symbol of Christmas, regardless of whether on the Africa front or in submarines .

At the same time, romanticizing and transfigured ideas of life on the front lines were sent back home with media coverage. Countless reports about "craft evenings" for Christmas gifts, which were held in bunkers, shelters and at the front, were spread in films and in magazines.

The propaganda companies issued special Christmas memorials (e.g. “Christmas celebrations of comradeship”) for individual units of the troops, but also for units of the SS. In the early years of the war, wounded soldiers were given the opportunity to send "speaking letters from the field" in a media-effective manner and with a high level of technical effort. As in World War I , there was fraternization between the war opponents on the front at Christmas . For example, in the winter of 1940/41, despite the war, hostile fighters met on Christmas Eve for a provisional Christmas devotion.

A large part of the reporting took up memorial reports about "Christmas in the field 1914-17". Numerous texts, letters from the field post and poems that were written during this period were republished in the Christmas publications of the main cultural office of the Nazi propaganda leadership. The poem Soldiers Christmas in World War II. by the writer Walter Flex , who fell in 1917 and was particularly venerated by the National Socialists, is one of the most prominent examples of taking up the myth of the soldiers' Christmas from the First World War. In almost all Christmas books, the address by a cavalry commander Binding from 1915 under the title German Art is to Celebrate Christmas was put in front.

With the change in the military situation, which was particularly evident on the Eastern Front, doubts about the war increased. In order to maintain the fighting morale of the troops, from 1942 onwards, propaganda shifted other goals to the fore. Instead of gaining “living space in the east”, the focus was now on defending the homeland and protecting the family. The Wehrmacht's Christmas writings presented this concern with great pathos. Even Christmas itself was declared an asset to be protected and to be defended. At Christmas 1942, the air force command took unusual measures to raise the morale of the troops trapped in Stalingrad: the dropping of artificial Christmas trees decorated with tinsel, stars and bells.

Field post is the link between home and the front

In order to demonstrate the unity of the national community, the close connection between the front and the homeland, the state paid special attention to a functioning field post . At school, children were asked to write letters to their father “in the field”. During the Christmas season in particular, the dispatch of Christmas parcels was organized by numerous mass organizations on "home evenings" and, to a certain extent, also monitored. The dimensions of the field post parcels were usually standardized and were not allowed to exceed one kilogram in weight, at times the permissible weight was reduced to 100 g, which posed a particular challenge for the relatives.

The preparation and sending of field post parcels, supported by prominent artists, was featured in the German newsreel and in numerous photo reports. The giving of presents to soldiers in the hospital by children or young girls was also one of the preferred motifs for Christmas reporting.

Numerous field post letters and eyewitness reports that have been handed down to us paint a completely different picture of the course of the “Christmas celebrations at the front”. Especially after 1942, when the military situation had changed significantly, there were increasing reports that the soldiers at the front were cut off from communication with their homeland and their families. Letters and field post parcels arrived late or not at all, and in many cases the supply situation was catastrophic, which led to increasing demoralization among the fighting troops, especially on these holidays.

Link Großdeutscher Rundfunk between home and front

Christmas speeches by Joseph Goebbels

Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels introduced the radio address as an annual Christmas ritual. The speeches at the German People's Christmas always reflected the current situation. In the course of the war, the Christmas address changed with the character of Christmas, initially it was the contemplative feast in the family, later the “feast of national hero remembrance”. The speech at Christmas 1939 was aimed primarily at those evacuated from the “Saar area” and the Baltic Germans who were “resettled in the Reich” as the “bearers of the greatest and most modern migration in modern history.” In 1940 Goebbels swore the German people to sacrifice and renounce and said: “That is why we want to hold our heads high at this war Christmas festival and feel as German people and members of a large ethnic family that deserves national happiness later, the more readily they accept the hardships of the present. It has always been the deeper meaning of Christmas not so much to feel peace as happiness, but rather to work and fight for peace. ”In 1941 the Christmas address was dominated by a constantly increasing, inflated cult of the leader. Goebbels called on the people to follow Hitler as a guarantee for victory.

One day before Christmas Eve 1942, the breakout of the German troops from the Stalingrad pocket failed . The downfall of the 6th Army was inevitable since that day at the latest. The morale and supply situation of the trapped troops was catastrophic at Christmas 1942. Of the estimated 195,000 encircled German soldiers, over 165,000 were not to survive the battle or subsequent imprisonment. Under the impression of the dramatically changing military situation, Goebbels gave a pathetic address on Christmas Eve. In the years that followed, the Ministry of Propaganda had their wording reprinted in countless Christmas publications. In this speech Goebbels invoked the German virtues as the prerequisites for final victory . He stylized Christmas as the feast of heroic commemoration and the day of a fateful decisive battle of the race.

“Our dead are the only ones who have to demand today, from all of us, at the front as well as at home. They are the eternal reminders, the voices of our national conscience that constantly urge us to do our duty.

The mothers in mourning for their lost sons may be reassured. It is not for nothing that they gave birth to their children in pain and raised them with worry. As men and heroes, they led the proudest and bravest life that a son of the fatherland can lead, and crowned it with the most heroic degree with which one can bring it to an end. They sacrificed themselves so that we could stand in the light […] Surrounded by the high night of the clear stars, we look into the future with faith and full of trust. As the poet says, the coming century will shine on us from a royal distance. It demands struggle and sacrifice from us. But one day it will bow to us. It is only a matter of time and patience, courage and diligence, faith and trust, the strength of our souls and the bravery of our hearts. "

In secret situation reports, the SS security service reflected " reports from the Reich " on the mood in the population that Goebbels' Christmas speeches triggered. On December 29, 1942, the report stated that the speech was particularly pleasing to the women because of its “objective dignity and solemnity”. At the same time, the report reported that the air alarms in the west on Christmas Eve did not want to create the feeling of "security at home".

On December 24, 1943, ten months after the Sportpalast speech , in which Goebbels tried to rhetorically fight against the war fatigue of the Germans due to the increasing number of military defeats, he put his Christmas address on the radio under the motto: "New birth of the political world". The last Christmas address on December 27, 1944 was no longer broadcast on the radio in the entire German Reich, since since October 1944 the first major German cities were no longer under the rule of the National Socialists. Enforced by slogans for perseverance and the swearing in belief in the final victory, Goebbels put this Christmas speech under the key phrase “battle of hard hearts”.

Christmas ring deliveries

In order to strengthen the feeling of solidarity between home and all sections of the front, the so-called Christmas ring broadcast was broadcast on the radio on Christmas Eve from 1940 to 1943 . The logistically complex radio program of the Großdeutscher Rundfunk had to be coordinated months in advance between the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft , the various Wehrmacht offices and propaganda companies as well as the Reichspost. Weeks beforehand were rehearsed, some of which were recorded.

In the first year of the war, 1939, the radio broadcast a specially designed program on Christmas Eve. There were circuits for this, including to Weimar and Munich. Rudolf Hess and Joseph Goebbels gave Christmas speeches. During the broadcast, Christmas greetings were sent to the front sections in the program. Between the fixed contributions, those responsible sent Christmas and folk music contributions.

The Christmas ring broadcasts from 1940 had a kind of "live character". However, there are doubts about the authenticity and the live broadcasts. In 1942 the program had a special dialogue character between the studio announcer and numerous outstations. The radio suggested a live connection between all front sections. The soldiers at the front exchanged greetings with their homeland. The audience wished for “spontaneous” Christmas carols, which were then sung together from all fronts. The last Christmas ring shipment was produced in 1943. On Christmas Eve 1944, the connections to the front sections were no longer available due to the military situation. Due to the destruction of many radio transmission systems, the technical possibilities to carry out such an elaborate circuit were lacking, especially since the front was already partially on the Reich territory.

Only a few audio documents of the Christmas ring broadcasts have survived (complete broadcast from 1940 and parts from 1942 and 1943). Numerous contemporary reports - even if they have to be viewed critically - show that these programs did not fail to have the intended effect. The mood pictures " Reports from the Reich " prepared by the SS security service recorded - with all historical caution - a positive response from the German population. The strategy of the Christmas ring broadcasts was propagandistic, but is not found in the "categories of a rhetorical-manipulative propaganda conception" of the classic kind. Today's media studies literature therefore regards the four broadcasts as a mixture of war propaganda , Nazi ideology and Christmas customs .

Christmas customs

The winter solstice celebration

- Solstice celebrations

Since the beginning of the 20th century, solstice celebrations have been organized by the German bourgeois youth movement, such as the Wandervogel and later the Bündische Jugend , as an important community-building element and emotional ritual . The solstice celebrations played a central role in the National Socialist festival calendar . As with other rituals and celebrations, the National Socialist ideologues used sacred elements. The designers supposedly derived the celebrated sun cult from Germanic mythology. In the first few years mainly local groups of the NSDAP, the Schutzstaffel, the Hitler Youth and the Association of German Girls staged the solstice celebrations. From 1935 the events were centralized. And after 1937, like in the Berlin Olympiastadion , they achieved mass character. According to the interpretation of the party designers, the winter solstice celebration should reinterpret Christmas as the festival of the "re-rising light". The process was also organized with guidelines. At the beginning of the war, the directive was added in 1939 with the addition “Cannot be carried out during the war during the blackout regulations”.

- Solstice celebrations

The following excerpt from such a guideline describes the process (the sacred parallels to church processions and church services can be seen):

“Silent march to the fireplace. Set up in a square, open to the smoke side. Torchbearers light the torches and step to the pile of wood.

- Fanfares

- Scharlied ( 'And when we march' - 'Holy Fatherland' or other)

- The torch bearers ignite the pile of wood. A fire spell can be spoken beforehand or a torch swing or a torch dance can be made.

- Scharlied ('flame up')

- Brief address by the high authority or the unit leader

- Weihelied ( ' We step to pray ' , 'Germany holy word' , if necessary drum roll)

- Throwing a wreath with sayings

- A short period of reflection

- Final word

- Leadership ceremony - German hymns

The march takes place as a torchlight procession. A fire station remains at the fireplace ”. Lighting torches and fires should emotionalize. The highlight was the fanning of straw-wrapped sun wheels , which were usually then rolled down to the valley. The content of the address was also given. The choices were “Winter solstice in belief, custom and custom” or “Winter solstice and Yule”. Often the pathetic song made Behold, lit the threshold of Baldur von Schirach an ingredient. The youth organizations issued badges that were worn on uniforms as a reminder of the celebrations .

The elaborate staging should create identity. The festival did not fail to have this effect, especially among young people.

- "Bringing the fire home"

In the sense of the "National Socialist party designers", the organization of solstice celebrations created a contrast to the more contemplative and traditional celebrations in the family circle. In order to indoctrinate the domestic Christmas celebrations and symbolically carry the solstice fire into the families, a new ritual was initiated from 1939: "Bringing the fire home". From the winter solstice fire, the candles on the town's central Christmas tree, the “Christmas tree of the people”, were to be lit with torches. On Christmas Eve the children were supposed to fetch the fire for the Christmas tree at home. Symbolically, the light of renewal should be carried into every family from a central fireplace . However, this custom was hardly spread among the population - not least because of the blackout measures caused by the war.

Christmas as the celebration of universal motherhood

Jesus Christ, who for many believers is the symbol of the long-awaited redeemer, did not fit into the ideology of the National Socialists, for whom there was only Adolf Hitler himself, the redeemer and savior on the “day of liberation”. The gospel was supplanted in the National Socialist Christmas literature by fairy tales like that of the child in the golden cradle and Mrs. Holle as guardian of unborn life and mother of life .

"The baby Jesus has now been slipped under the German mother and the hearty lullabies have been repositioned on the manger in Bethlehem in Palestine."

After a few years of National Socialist rule, the Christian Christmas story was openly and openly polemicized and this was replaced by a representation that, in addition to the rooted biblical design elements, such as the crib, also contained elements from German fairy tales. From 1938 onwards, Frau Holle was increasingly stylized in these Christmas stories as the “mother of life” and traced back to Freya , the Germanic goddess of love and marriage .

In the early years of National Socialism, Christmas was already elevated to the status of the “Festival of General Motherhood”, the “Mother's Night”, and the German mother was stylized as a substitute for the Mother of God . For this purpose, the NSDAP donated the German Mother's Cross of Honor (Mother's Cross) at Christmas 1938 , which was awarded to mothers with many children, exclusively to those with an Aryan certificate.

Motherhood as the “germ” for the pure Aryan race , consisting of mothers and soldiers, was glorified and glorified in countless poems and writings, such as B. in the farmer mother-to-be or in the widespread poem Mothers Christmas :

"This is how we see the

mothers standing brightly in the glow of the stars and the candles on Christmas Eve ,

they had to walk quietly through the night and hardship and pain, so

that the people of tomorrow can become mothers and soldiers."

During the war, women became the most important target group for National Socialist propaganda at Christmas time, because the psychological burden of war lay on them to a particular extent .

Pre-Christmas, the National Socialist Christmas calendar

With the suppression of Christian Christmas customs from official linguistic usage and due to the lack of paper due to the war, the traditional Advent calendar also fell victim to censorship, Christian motifs were replaced by fairy tale and animal figures. Due to its great popularity, the children's advent calendar was replaced by a pre-Christmas calendar , published by the main cultural office in the Reich Propaganda Office of the NSDAP.

A selection of fairy tales and Nazi Christmas songs, craft instructions for wooden Christmas tree ornaments in the form of runes and sun gears, so-called Weihnachtsgärtlein and Klaus trees from potatoes, baking instructions for Sinn pastries, the calendar contained a clear focus on military content, such as the leaf We build snow shelters and Paint snowmen or children (suggested motif 1942: burning Russian tanks and destroyed English ships). The content of the so-called ancestral and clan research and the derivation of the meaning of runes and symbols took up a large part of the content .

The pre-Christmas calendar appeared in 1942 and 1943 with almost identical content. However, the design of the calendar sheets was adapted to the respective military situation at the front. While in 1942 the calendar sheet "1 day until Christmas" was provided with an ornamental garland, in which all front sections from the Atlantic to Africa, the east to Norway were recorded, this element was retouched in 1943 due to the changed course of the front . The accompanying text was also adapted to the military and political situation: The deletion of the term Greater German Reich in the 1943 calendar documents the changed military situation on the fronts.

In the years of war and peace, |

In the years of war and peace, |

decoration

In numerous family and women's magazines, handicraft instructions for Christmas and table decorations were traditionally distributed in the run-up to Christmas. In the mass publications from the main cultural office of the NSDAP's propaganda management, the pre-Christmas calendars and the war Christmas almanacs that were published at the beginning of the war, preference was given to promoting naturalistic Christmas decorations that were supposedly of Germanic origin.

From fir and box tree branches , apples, nuts, wooden discs and potatoes, candle holders were made, which were often provided with Germanic or Nordic symbols. The decorative objects advertised with preference included z. B. the so-called Klausenbaum consisting of potatoes and fir branches and the Julleuchter , which were decorated with Germanic symbols. In addition, the classic Advent wreath made of fir green was "modified" to a green wreath in the form of a swastika with a central candle.

In the SS , some leaders were close to occult ideas and the German cult, despite the official classification of occult associations as sects hostile to the state in 1933 . From 1938 onwards, Heinrich Himmler presented the members of the SS with a so-called Julleuchter and a Julteller as a Christmas present. These candlesticks, made of fired clay and decorated with runes and old Germanic symbols, were mostly manufactured in large numbers for the SS-owned porcelain factory Allach in the Dachau and Neuengamme concentration camps . In addition to the ceramic Julle candlesticks, numerous wooden models, mostly with a central sun disk or other motifs from Germanic mythology, were widespread.

Solstice wreath and fairytale garden

The traditional Advent wreath , which goes back to a Protestant tradition of the 19th century, should be replaced by the "midsummer wreath " - usually with sun wheel or Viking motifs - or the "light wreath" according to the ideas of the party designers. The candles on the wreath no longer symbolized the four Sundays in Advent, but rather the four seasons as "wishing lights". Matching the lighting of the “wish-lights”, light slogans were presented, which were “suggested” in the corresponding Christmas booklets. The nativity scene, inherited over generations in many families , was no longer in keeping with the times and was supposed to give way to a forest landscape with animal motifs made of wood or cardboard, which was advertised under the name of Christmas garden or fairy tale garden . At the same time, numerous publications were published in which the Christmas story was denigrated: The worshiping shepherds were presented as a folk group who "went blowing through the hallways at the winter solstice." Instead of the traditional Christmas story, fairy tales were now mostly presented. The story of Mrs. Holle played a central role, new romanticizing fairy tales such as “Christmas in the Woods” by Hildegard Rennert were spread with great media effort in order to increase the acceptance of the “fairy tale garden” as a replacement for the Christmas crib.

Lights sayings

In addition to “bringing the fire home”, the National Socialists tried to integrate another new custom into the design of the family celebrations of German Christmas with the introduction of the light slogans in order to counteract the danger of war disenchantment during war. When lighting the wishing lights on the midsummer wreath, verses were recited that were given as examples in the “Pre-Christmas” calendars and were always intended to establish a connection between home and the front.

Father:

The sun has rolled through the year,

now it's weak and small.

But soon it will be

big and full of warmth with its gold .

So we decorate the solstice wreath

for its new run

and put

four red candlesticks on it with a bright shine :

First child:

I offer my light to my mother, who

cares for us children all year round.

Second child:

My light should be on for all people

who cannot celebrate Christmas today.

Third child:

I bring my light to all soldiers

who bravely did their duty for Germany.

Fourth child:

My wishful light is given to the Führer

who always thinks of us and Germany.

“The children can also say more sayings that the mother made and taught the children before Christmas. You can relate to loved ones, to your home country or to your father who may be absent. "

Jultanne

The decorated Christmas tree has long been the symbol of German Christmas. The most inherited Christmas tree decorations with angels, glittering balls, tinsel , angel hair and Christmas tree tops have now been called old-fashioned kitsch. During National Socialism, the Christmas tree was viewed as an offshoot of the Germanic world ash , without any scientific justification, and stylized as a “symbol of German Christmas”. At the same time, suggestions were made as to how the “species-appropriate German” light tree, the Jultanne , should be designed: Apples, nuts and homemade pastries were supplemented with fretwork motifs of animals and Germanic symbols, runes or purchased Yule jewelry . The July or Christmas decorations were similar to traditional Christmas tree balls - but with embossed runes, swastikas and numerous Germanic symbols. From 1934 the swastika was officially approved as a Christmas ornament . In the run-up to Christmas, the collection campaign “Jewelery for the Christmas tree” was carried out, in which collectible figures from the winter aid organization for the light tree were sold. The glass Christmas tree top was replaced by self-made “ sun wheels ”, and wooden frames in the form of wheel crosses often served as Christmas tree stands.

In some households the Julbogen decorated with boxwood, apples and nuts and Germanic symbols was set up, which goes back to the Jöölboom (also called Friesenbaum), which is still traditionally widespread in North Friesland in northwest Schleswig-Holstein . The Julbogen propagated by the National Socialists was often decorated with homemade or wooden Germanic symbols, norns and four candles. The shape of the arch should represent the symbol of the course of the sun and unite the symbols of fertility , light and new life. Proposals for the production and decoration of such Julbögen were disseminated in many women's magazines, such as the Nazi women's observatory .

Sinngebäck

The Nazi influence also extended to the production of the Nazi holiday pastries. The ever-popular and traditional Christmas stollen and the Christmas cookies in the form of hearts, stars and fir trees should increasingly give way to shaped breads with new motifs, such as runes, symbols, wheels of the year and sun as well as Germanic animal symbols from mythology, such as the Juleber or the July deer . In numerous publications, such as the NS-Frauen-Warte , recipe sheets of the "contemporary household", in Christmas books and "pre-Christmas calendars", but also by well-known baking ingredient manufacturers, appropriate recipes for such baked goods were distributed and the Germanic symbols explained. The meaningful pastries in the form of victory and Odal runes as well as annual wheels, which were primarily not intended for consumption, but as decoration of the Yule arch and for the species-appropriate Christmas tree or light tree, were particularly advertised - including in the German weekly newsreel . Even the manual activity of making baked goods was transfigured into a spiritual act:

“This is no longer your ordinary gingerbread. Somehow that has a secret purpose. That is why one must not cut out the characters by the dozen with the sheet metal form. You have to shape with your hand and it has to be done reverently. "

During the war before Christmas, new “contemporary” recipes were constantly being distributed in women's and family magazines. In addition to long-lasting and nutritious Christmas biscuit recipes for field post parcels , suggestions were made on how biscuits could be made without or with little use of fat and sugar, such as war crumble cake , barley brittle or honey cake without fat .

During the war, the National Socialist ideologues placed high value on the production of Christmas cookies in terms of the morale of the fighting troops. The Reich Committee for Economic Enlightenment therefore published numerous makeshift recipes and surrogates in the course of the deteriorating supply situation . The manufacturers of baking ingredients also often published their modified recipes with an ideological foreword in which the value of the domestic work of women was equated with the war effort of men. Special allotments for food shortly before Christmas were supposed to ensure during the war that Christmas baking at home could be carried out even when the supply situation was tense.

The Sunnwendmann

One of the central symbolic figures of the Christian Christmas festival is St. Nicholas in his function as a bringer of gifts . The saint, especially venerated by children as a benefactor and bringer of gifts, was reduced by the National Socialists to a Christian interpretation of the Germanic god Wodan , who rides on a white horse over the earth and announces the winter solstice. The figure of St. Nicholas was consequently displaced from linguistic usage by a somewhat sinister figure who was called the Schimmelreiter , the Rauhe Percht , the German servant Ruppricht or Santa Claus or Sunnwendmann . In many areas these rather frightening figures appeared as companions of St. Nicholas in the customs and took a much more central position under the new ideological guidelines.

The National Socialist folklorists relied in particular on the depiction of Knecht Ruprecht in Jacob Grimm's work, German Mythology . They linked folk Nazi symbolism with Germanic-pagan mythology, folk customs and a pseudo-religious reference in order to increase the acceptance of the newly created figure of the gift-bringer. St. Nicholas' Day, December 6th, was renamed "Ruprechtstag" in official parlance from 1940. In numerous Christmas books, the figure of St. Nicholas was downright mocked and Santa Claus was portrayed as the “real benefactor”.

Christmas carols

Many German Christmas carols have a very old tradition and go back to chants that were sung during the festival services. Originally in Latin , many were partially or fully translated in medieval times, for example In dulci Jubilo - Now sing and be happy . Another root of Christmas carols , such as B. von Joseph, dear Joseph my , is in the Christmas custom of the symbolic "infant cradle" of the baby Jesus in the manger, which was especially common in medieval convents. The traditional Christian Christmas carols were deeply anchored in people's minds and were sung at all Christmas celebrations.

The National Socialist ideologues tried to systematically “de-Christianize” and “Germanize” the Christmas carols by means of rephrasing and to eliminate biblical or religious references; at most “ God ” was named as a religious code. Some of them, like daughter of Zion, you are happy , you dear holy pious Christian or born in Bethlehem , were directly banned by the censors at official celebrations. On the other hand, the rulers considered O Tannenbaum and Tomorrow, children, there will be something “harmless” . Others, such as Silent Night, Holy Night or the pieces listed below, were "repackaged" and in some cases completely distorted. Despite the intensive dissemination of the new song texts via the mass media and at major events, they were not able to prevail against the traditional Christmas carols, especially in the family circle.

New Christmas carols

New "Christmas songs", rooted in the National Socialist ideology, were massively disseminated on the radio, in schools and at Christmas parties of mass organizations. The new Christmas carols that are often played include In this clear, starry night , The valley and the hills are covered in snow , The snow has fallen softly and the soldiers' Christmas . Most of the National Socialist Christmas carols were characterized by pompous lyrics with exaggerated pathos.

The best-known among them, High Night of the Clear Stars (1936), comes from Hans Baumann , who made a name for himself with the National Socialists in 1932 with the song of the German Labor Front , The rotten bones tremble . Seldom received after 1945, Heino reissued it on a Christmas album published in 2003.

Other Christmas carols that were composed during National Socialism continued to be used after the Second World War. This includes the Christmas carol, which was first published in 1936 in HJ-Liederblatt 65, It is now Christmas time .

Manipulated Christmas carols

Several new poems existed from some traditional songs, such as Es ist ein Ros sprung , which were sung at official celebrations, but were not widely used in family circles. Even the most famous German Christmas carol Silent Night, Holy Night was rewritten in 1942: the “dear, most holy couple” became the “shining tree of lights” and “Christ, in your birth” was rewritten as “Become a light seeker all!”. One of the repositioned Christmas carols, which was originally known as the Aargauer Sterndrehermarsch , has been preserved to the present day in a slightly modified version of the repositioning by Paul Hermann (1939) in the songs. The following comparison illustrates some of these shifts.

| Catholic hymn (1599) | Redesigned in 1942 | Redesigned in 1943 |

|---|---|---|

A rose rose |

A light has arisen for us |

Now it shines in the heart |

| Original version 1837 | Redesigned in 1943 |

|---|---|

Little children, come, oh come all! |

Come, little children, come here |

| Original version 1895 | Redesigned in 1943 |

|---|---|

3. Soon it will be holy night, the |

3. Sun rises |

| Aargau 1902 | Re-writing in 1939 |

|---|---|

A time has arrived for us, |

A time has come for us, |

| 1818 | Redesigned in 1942 |

|---|---|

Silent Night Holy Night! |

Silent night, holy night |

Excursus: Christmas presents from 1933 to 1945

Christmas presents reflect to a large extent the economic situation of society. In the early years of National Socialism, adults had everyday items such as kitchen utensils, clothing, decorative objects for the apartment, books and often also sweets and wine or spirits on their wish lists . In the mid-1930s, a people's receiver was increasingly given for Christmas , among those in need and war invalids, also financed by funds from the Dr. Goebbels radio donation (until 1942: 150,000 devices).

In addition to the traditionally widespread Christmas gifts for children such as parlor and board games, musical instruments, books, clothing, dolls and doll accessories for girls and technical toys and sports equipment for boys, there was a tendency from the mid-1930s to see that the proportion of war toys in the Christmas catalogs department stores and toy stores and newspaper advertisements increased. In addition to fortresses, tanks, tin soldiers and Elastolin figures in Jungvolk , HJ, SA and SS uniforms, toy catalogs also advertised the “Führer’s Car” from the Tippco company . In addition to fighting and military figures, a large selection of accessories and equipment was provided, which should convey a picture of soldierhood, which was not only characterized by combat, but also by camaraderie and care.

As early as 1933, the “Reich Association of German Toy, Basketware and Pram Dealers” was founded, which, in addition to traditional toys, increasingly also offered toys that had a National Socialist character. In addition to traditional Christmas advertisements, advertisements for the purchase of subscriptions to the Reichszeitung Die HJ - the battle paper of the Hitler Youth or Das Deutsche Mädel - were placed as Christmas gifts in newspapers from the mid-1930s . At this time, equipment or parts for a uniform of the Hitler Youth or the Association of German Girls were also on the wish lists of young people.

The National Socialist educational goal , the dissemination of the National Socialist ideology as far as possible in all public and private areas of life, is also reflected in the selection of the toys that are preferred. While the girls were traditionally prepared for their future mother role with dolls, dollhouses decorated with National Socialist and folk decorations, and the corresponding accessories, the boys were introduced to arms service in a playful way as early as the mid-1930s.

Current political events were picked up in board and card games and processed for propaganda purposes, such as the board game Reichsautobahnen under construction . On the occasion of the " return of the Ostmark " and the Sudetenland to the Reich in 1938, the board game Reise durch Großdeutschland was launched .

During the war, military issues were taken up in the design of toys, especially by toy companies that were " Aryanized ", such as the Nuremberg companies JWSpear & Sons and Tipp & Co. This included, in particular, campaigns by the Wehrmacht , such as the naval war against England in the board game We drive against Engeland (1940), bombs on England (1940), the Wehrschach (1938) or the "Adler air defense game". The aim of the increasing militarization of the toy was a targeted indoctrination of the children and young people as well as a preparation for the future war effort. Even the National Socialist racial policy should be conveyed playfully to eight to twelve-year-olds, such as the board game Jews out or the anti-Semitic children's books from the Stürmer publishing house The poison mushroom and no fox on green heath and no Jew in his oath - a picture book for big and small Show small .

During the war, the people's Christmas gifts also changed. Many companies were converted to war-essential production, consumer goods and toys were barely produced. In 1943 a ban on the production of toys was imposed. Numerous magazines now contained sections with instructions on how to make Christmas presents from “leftovers” and materials from nature. Garments were reworked, scraps of fabric sewn into doll clothes, for example. In order to compensate for the lack of commercially available toys, Christmas decorations and candles, Christmas gifts were tinkered and exchanges for clothes and everyday objects were set up on so-called “home evenings” of the Hitler Youth, the Association of German Girls and the National Socialist Women's Association.

The reworking of unusual materials, such as bullet casings and broken utensils, into gifts was characteristic of the last Christmas of the war. In the run-up to Christmas, advertisements were printed in magazines in which customers were put off for a certain product until after the war.

Feedback from the German population

The National Socialist party organizers officially emphasized that the National Socialist Christmas celebrations did not aim to suppress the influence of the churches. However, the congruence of the course and the design of the events with church celebrations and the overlapping dates show that the aim was to secularize Christmas and to reduce the influence of religion in public and private life. The religion and Christian traditions were firmly anchored in large parts of the German population.

What influence the National Socialist propaganda had on the family celebrations can hardly be determined. Many surveys are based on the evaluation of contemporary witness reports. While the public collections and Christmas celebrations, at least in the first years of National Socialist rule, were able to create a feeling of togetherness in broader sections of the population - especially among young people - other rituals initiated by the party organizers failed to have an effect. In particular, the repositioned Christmas carols were not widely used in private circles outside of the mass events. An exception is the song " High Night of the Clear Stars ", which was widely distributed at all mass events and on the radio, but could not replace the most famous Christmas carol Silent Night . This fact was evident in the design of the Christmas editions of the German weekly newsreel and the Christmas ring broadcasts . To create a bond, the popular Christmas carol Silent Night - in the original text - was mostly used as background music or as the end of the program .

Many of the proposals initiated by the Reich Propaganda Leadership for the organization of German Christmas were only used very subordinately even in the National Socialist mass media; instead, traditional Christmas symbols were used. In particular, the traditional Christmas tree with candles and tinsel could not be replaced by the National Socialist light tree with wooden decorations in the form of runes. Even in the German War Christmas Almanacs published by the Reich Propaganda Ministry, in which Nazi Christmas decorations were advertised, a photograph of Heinrich Hoffmann was printed showing Adolf Hitler in front of a Christmas tree decorated with lametta.

The substitute rituals, such as “bringing the fire home” and the “Christmassy cult of the dead”, could not prevail among the population. One reason for this is that many Germans sought refuge in their faith again during the war and many public events (winter solstice celebrations, giving presents in the national community, etc.) could not be held due to the war-related impairment. Especially during the war, the German population followed the Christian message of peace and sought consolation and support in religion.

The effect of ideologically influenced toys and children's books on National Socialist education is difficult to assess. Military toys were traditionally a favorite Christmas wish for boys even before 1933. Especially at the beginning and during the first years of the war, the share of war-related and ideologically influenced toys increased until toy production came to a standstill due to the war in 1943. Many contemporary witnesses can still remember the existence of such games and books in the household.

Despite intensive efforts by the National Socialist ideologues to secularize the Christian Christmas festival, it was not possible to introduce Christmas as the “festival of the awakening nature” for large parts of the population. Only a small part of the population accepted the newly created Christmas rituals. The Führer cult, which also played an important role in the celebration of the Christmas season, was the most successful instrument of Nazi propaganda in terms of mass impact.

literature

swell

- Alexander Boss: celebration book of the German clan . 1st edition. Widukind-Verlag, Berlin 1941.

- Wilhelm Beilstein: Light celebration, meaning, history, custom and celebration of German Christmas . 5th edition. Deutscher Volksverlag, Munich 1942.

- Karl-Heinz Bolay : German Christmas: A guide for community and family . 1st edition. Widukind-Verlag, Berlin 1941.

- Main cultural office of the Reich Propaganda Leadership of the NSDAP: Pre-Christmas . Ed .: Thea Haupt. F. Rather Nachf., Munich 1942.

- Main cultural office of the Reich Propaganda Leadership of the NSDAP: Pre-Christmas . Ed .: Thea Haupt. F. Rather Nachf., Munich 1943.

- Main cultural office of the Reich Propaganda Leadership of the NSDAP: German War Christmas . F. Rather Nachf., Munich 1941.

- Main cultural office of the Reich Propaganda Leadership of the NSDAP: German War Christmas . F. Rather Nachf., Munich 1942.

- Main cultural office of the Reich Propaganda Leadership of the NSDAP: German War Christmas . F. Rather Nachf., Munich 1943.

- Mathilde Ludendorff , Erich Ludendorff : Christmas in the light of race knowledge . Ludendorffs Verlag, Munich 1936.

- Helmuth Miethke : Winter solstice, Christmas tree and Santa Claus . In: Treuhilde - sheets for German girls . tape 47 , no. 5 . Berlin, S. 66-68 .

- Gerhard Müller: Christmas of the Germans. From history and customs at Christmas time . Greiser, Rastatt 1945.

- Hans Niggemann: Festivals and celebrations of the German type: Christmas . Hanseatic Publishing House, Hamburg 1934.

- Carl Schütte: Festivals and celebrations of the German kind: Christmas . Hanseatic Publishing House, Hamburg 1934.

- Paul Zapp : Germanic-German Christmas: Proposals and suggestions for the Yule Festival . Gutbrod, Stuttgart 1934.

Representations

- Judith Breuer, Rita Breuer : Not because of Holy Night - Christmas in political propaganda . 1st edition. Verlag an der Ruhr, Mülheim an der Ruhr 2000, ISBN 3-86072-572-6 , p. 63-163 .

- Nadja Cornelius: Genesis and change of festive customs and rituals in Germany from 1933 to 1945 . In: Cologne ethnological contributions . tape 8 , 2003, ISSN 1611-4531 .

- Richard Faber , Esther Gajek: Political Christmas in antiquity and modernity - For the ideological penetration of the festival of festivals . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1997, ISBN 3-8260-1351-4 .

- Michael Fischer: Father stands in the field and keeps watch: The German War Christmas script as a means of propaganda in the Second World War . In: Michael Fischer (Ed.): Song and Popular Culture / Song and Popular Culture . tape 50/51 , 2005, ISSN 1619-0548 , pp. 99-135 .

- Doris Foitzik: Red Stars, Brown Runes - Political Christmas between 1870 and 1970 (= Intern. University publications . Volume 253 ). Waxmann, Münster 1997, ISBN 3-89325-566-4 .

- Women's group fascism research: Mother cross and workbook: On the history of women in the Weimar Republic and under National Socialism . 2nd Edition. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-596-23718-1 .

- Birgit Jochens: German Christmas: A family album 1900–1945 . 6th edition. Nicolai, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-87584-603-4 .

- Walther Hofer : National Socialism, Documents 1933–1945 . 50th edition. Fischer Bücherei, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-26084-3 .

- Kerstin Merkel, Constance Dittrich: Playing with the Reich - National Socialist ideology in toys and children's books . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-447-06303-6 .

- Heinz Müller: miniature brochures of the winter relief organization WHW / KWHW u. a. 1937-1944 . Ed .: Sammlerkreis Miniaturbuch eV Stuttgart 1997.

- Uwe Puschner , Clemens Vollnhals : The Völkisch religious movement in National Socialism. A relationship and conflict story . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-525-36996-8 .

- Michael Salewski , Guntram Schulze-Wegener : War year 1944: in large and small . In: Historical communications (supplement) . tape 12 . Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 978-3-515-06674-7 .

- Rudolf Simek : Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X .

- Josef Thomik: National Socialism as a Substitute Religion - The magazines "Weltliteratur" and "Die Weltliteratur" as carriers of National Socialist ideology . Einhard, Aachen 2009, ISBN 978-3-936342-73-4 .

- Klaus Vondung : Magic and Manipulation. Ideological cult and political religion of National Socialism . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1971.

- Ingeborg Weber-Kellermann : The Christmas festival - a cultural and social history of the Christmas season . CJ Bucher, Munich / Lucerne 1987, ISBN 3-7658-0273-5 , p. 232 .

- Knut Schäferdiek : Germanization of Christianity? In: The Evangelical Educator . tape 48 . Frankfurt am Main / Berlin / Munich 1996, p. 333-342 .

- Dominik Schrage : “Sing all of us together at this minute” - sound as politics in the 1942 Christmas ring broadcast . In: Daniel Gethmann, Markus Stauff (Hrsg.): Politiken der Medien . sequencia 11. Diaphanes, Zurich / Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-935300-55-7 , p. 267–285 ( lmz-bw.de [PDF; 166 kB ; accessed on June 5, 2017]).

- Bernhard Welte : Ideology and Religion . In: Franz Böckle, Franz-Xaver Kaufmann, Karl Rahner, Bernhard Welte in connection with Robert Scherer (ed.): Christian faith in modern society . tape 21 . Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1980, p. 79-106 .

Web links

- Michael Fischer: High Night of the Clear Stars (2007). In: Popular and Traditional Songs. Historical-critical song lexicon of the German Folk Song Archive

- Sound document - final part of the Christmas ring broadcast 1942 (4:45 minutes; MP3; 2.3 MB) on the homepage of the " Rundfunkmuseum der Stadt Fürth "

- The speaking field post letter. In: German Broadcasting Archive . December 2002, archived from the original on June 21, 2006 .

- Daniel Huber: Führer Christmas. 20 minutes , January 26, 2010, archived from the original on January 16, 2013 (review of the exhibition in Cologne, with several images).

- Christmas 1941 Hitler celebrates in private circles (film recording)

- Report of the German newsreel 1942 A comprehensive propaganda report on Christmas 1942, backed up with the "new" Christmas carols, such as "High Night of the Clear Stars"

- Philipp T. Haase: How Karlsruhe celebrated the people's Christmas "- National Socialist Christmas Cult in Baden 1936 . Commission “History of the State Ministries in Baden and Württemberg during the National Socialism”, Heidelberg, December 21, 2015

- Sven Felix Kellerhoff: This is how Adolf Hitler celebrated Christmas. In: Welt Online . December 25, 2018 .

- Stefanie Oswalt: Nazi propaganda Christmas under the swastika , contribution from December 14, 2014 in the program Religionen by Deutschlandfunk Kultur

Quotes and Notes

- ↑ The creation of a substitute religion is controversial in the research literature. See: “Here the claim is very clearly formulated not to be a substitute religion, but something that replaces religion as the founder of meaning in life, a religion substitute that in practice could not do without cultic exaggeration.” P. 347 & “In particular in In the context of National Socialism, the concept of political religion has been increasingly discussed in recent years. ”(Before 2012)“ Belief in the existence of a supernatural power, a conception of the hereafter, a doctrine of salvation and other things that we in the Not finding National Socialism. ”In: Ernst Piper: National Socialism stands above all creeds. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2012, p. 344.

- ↑ "Much more problematic and in any case more political is what has arisen in the environment of the Völkisch and thus also the Nazis: that the Christians, and the Christians are then only a special case of Jews, the Germans, the Teutons would have robbed Christmas . In its original form, this was the 'Yule Festival', at least the winter solstice: the festival on which Wotan roams through the air with the dead warriors in the form of the 'Wild Hunt'. And this original festival has to be restored, the dispossessed, Judeo-Christian Christmas festival has to be regermanized. ”In: Richard Faber in conversation with Johannes Wendt: Political Christmas in antiquity and modernity. In: Richard Faber , Brigitte Niestroj, Peter Pörtner (Eds.): Philosophy, Art and Science. Memorandum for Heinrich Kutzner . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2001, ISBN 3-8260-2036-7 , p. 197.

- ↑ "To our detriment, a foreign worldview knew how to seize this most intimate German festival and to ascribe foreign thoughts and ideas to it, so that today, with the clear understanding of a German worldview, we have to separate and sift through the real and the unreal". In: Karl-Heinz Bolay: German Christmas - A guide for community and family . Widukind-Verlag, Berlin 1941, p. 6.

- ↑ Führer Headquarters October 14, 1941 as guest of Reichsführer SS H. Himmler; Hitler says: “One cannot take one thing from the masses as long as they do not already have the other. Rather, the better must already have taken possession of it before - what matters - the little good fades in its imagination. It is a mistake to believe that a new, in order to replace an old, only needs to be brought closer to the old. It seemed to me unspeakably foolish to revive a Wotan cult. Our old mythology of gods was out of date, was no longer viable when Christianity came. It only disappears what is ripe to go under! ”In: Heinrich Heim, Werner Jochmann (Ed. And commented): Adolf Hitler - Monologues in the Führer Headquarters 1941–1944. Special edition. Orbis Verlag, Munich, 2000 (originally published by Albrecht Knaus Verlag, Harburg 1980), p. 84.

- ↑ Faith is more difficult to shake than knowledge [...] Whoever wants to win over the masses must know the key that opens the door to their hearts. In: Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. Munich 1925, p. 227, quoted in: Klaus Morgenroth (Hrsg.): Hermetik und Manipulation in Fachsprache. G. Narr Verlag, Tübingen 2000, ISBN 3-8233-5360-8 , p. 152.

- ↑ Note 17: The statements made by Hermann Rauschning, Talks with Hitler, Zurich 1940, p. 51, about the reorganization of church customs and festivals in Germanic-National Socialist guise, again only refer to questions of organization and direction and their mass psychological effectiveness. However, they are already pointing in the direction that was later taken primarily by the NSDAP's protection squad with the organization of celebrations and " Jul-Leuchtern " personally donated by Himmler for deserving followers . In: Friedrich Zipfel: Church struggle in Germany 1933–1945. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1965, p. 8.

- ↑ Thuringia played a pioneering role p. 1; In the politically and economically tense phase (the 1930s) there were state elections on December 8, 1929. The NSDAP received 11.3% of the vote, not least because of the rejection of the Young Plan , which brought in sympathy p. 28; On January 23, 1930 the NSDAP first took part in government p. 30 In: Nico Ocken: Hitler's “Brown Stronghold” - The Rise of the NSDAP in the State of Thuringia (1920–1930). Diplomica, Hamburg 2013.

- ↑ "School prayers included phrases such as 'Germany awake', 'give us the heroic courage of the Savior' or 'make us free from deceit and betrayal.'" In: Nico Ocken: Hitler's "Braune Hochburg" - The Rise of the NSDAP in the State of Thuringia ( 1920-1930). Diplomica, Hamburg 2013, p. 32.

- ↑ Führer, my Führer, given to me by God / Protect and keep my life for a long time! / You saved Germany from deepest need, / I thank you today for my daily bread. / Stay with me for a long time, don't leave me, / Führer, my guide, my faith, my light. In: Amrei Arntz: National Socialist Christmas - Celebration and celebration of the "German Christmas". December 29, 2009, accessed March 30, 2012.

- ↑ Postage stamps with the motif of the winter relief organization

- ↑ The UFA Tonwoche 438 of December 6, 1939 reported that 34 million Christmas figurines were made for the WHW in "emergency areas" of the Bavarian and Bohemian Forests and the Ore Mountains.

- ↑ Wolfsschanze January 6, 1942, Hitler says: “The wool collection now, it's really touching what's happening! People donate their precious things here, but they must feel that each embezzlement omitted. It must be certain that this will come to the man! The smallest muschik can wear the most precious fur, but God bless him who grabs the fur on the way to the soldier! ”In Heinrich Heim, Werner Jochmann (Ed. And commented): Adolf Hitler - Monologues in the Führer Headquarters 1941–1944 . Special edition. Orbis Verlag, Munich, 2000 (originally published by Albrecht Knaus Verlag, Harburg 1980), p. 182.

- ↑ The use of sacred and folk symbols of Christmas (such as the Christ child, angel, crib, Knecht Ruprecht , poinsettia, Christmas tree, Advent wreath) should by no means be prohibited by the guideline for advertising; rather, particular attention should be paid to taste with such advertising motifs become. in: Guideline of the retail business group for Christmas advertising. Berlin, November 1936.

- ↑ "However, it should always be checked whether the connection of those Christmas symbols that emphasize the sacred and folk character of the festival with the advertising of goods does not appear intrusive and therefore contradicts the healthy public perception (e.g. Christ child, angel, crib, servant Ruprecht, poinsettia, Christmas tree, Advent wreath, etc.) ”. In guidelines of the Retail Business Group for Christmas advertising . Berlin, October 1936.

- ↑ “Once a year, on holy night, the dead soldiers leave the watch they stand for Germany's future, they come into the house to see what kind and order they are. They step into the festive room in silence - the kick of the nailed boots, you can hardly hear it. They stand still with father and mother and child, but they feel that they are expected guests: a candle is burning on the fir tree for them, there is a chair for them at the set table, the wine glows dark for them in the glass. [...] When the candles on the tree of light have burned to the end, the dead soldier gently places his earth-encrusted hand on each of the children’s young heads: We died for you because we believed in Germany. Once a year after the holy night, the dead soldiers go back to perpetual vigil. ”Main cultural office of the NSDAP: Christmas in the family. In: Hauptkulturamt in the Reich Propagandaleitung of the NSDAP (Hrsg.): German war Christmas. Franz Eher Nachf, Munich 1943, p. 120.

- ↑ Let us take a breath in front of our Christmas tree and consider that Bolshevism has eradicated Christmas stump and stalk and that Americanism has made it a hype with jazz and bars, then we know that we also have Christmas in war, no especially in war must be celebrated in the family, because our soldiers are on guard so that we can keep and organize this festival. in: Main cultural office of the NSDAP: Christmas in the family. In: Hauptkulturamt in the Reich Propagandaleitung of the NSDAP (Hrsg.): German war Christmas. Franz Eher Nachf, Munich 1943, p. 114.

- ↑ The dead “not only continue to stand by our side in a Germanic manner, but also stay among us at our festivals. On Holy Night of the year we also commemorate the mother of our people, whose commitment gives us faith in the great future, the great solstice of our people. ”In: Oberbergischer Bote. The daily newspaper of the creative people. Official newspaper of the NSDAP / Kreisblatt des Oberbergischer Kreis, December 4, 1941.

- ↑ Soldiers who were wounded on the hand were given this opportunity. The recordings were mostly cut on sound foils , so-called decelith foils, in hospitals , which could be played on every record player or gramophone with an attached special needle at 78 revolutions per minute. The speaking field post letter. In: German Broadcasting Archive . December 2002, archived from the original on June 21, 2006 ; accessed on December 13, 2017 .

-

↑ Soldiers Christmas in World War II

Lonely watch,

snowy night!

The frost creaks in the ice

The storm sings harshly,

The peace that I praise,

It is under spell.Brandhelle praises!

Murder, hatred and death,

they stretch out

above the earth To a cruel threatening gesture,

That peace will never be,

oath hands bloody red.What frost and suffering.

An oath burns me,

It glows like a fire

through sword and heart and hands.

It ends how it ends -

Germany, I'm ready. - ↑ “None of our enemies knows the magic, the power of the tree of lights on our mind, on our strength. Let's stay true to the German way! Because the German way is something greater, a German virtue, one above all else, that is loyalty! [...] And isn't the war a big German thing? So let's stay true to the war, comrades! If we remain loyal to him to the end, we also remain loyal to the fatherland. With this certainty, today's war Christmas will not become a sentimentality for us, not a surrender to wistful thoughts, but a symbol and visible sign of tremendous togetherness in our German way. “It is German way to celebrate Christmas! In: Hauptkulturamt in the Reich Propagandaleitung of the NSDAP (Hrsg.): German war Christmas. Franz Eher Nachf, Munich 1943, p. 41.