advent Calendar

An advent calendar (in Austria Advent Calendar ) heard since the 19th century to the Christian tradition in the time of Advent . The calendar is common in various forms and forms, but usually shows the remaining days until Christmas .

Advent calendars count either in relation to the church year or to the civil calendar . Advent calendars that refer to the church year cover the whole of Advent (the first Sunday in Advent can fall between November 27th and December 3rd) through Christmas or the Three Wise Men , while Advent calendars start on December 1st and December 24th , on Christmas Eve . Like the Advent wreath , advent calendars are intended to “shorten” the waiting time until Christmas and increase anticipation.

Originally coming from a Lutheran custom in Germany, Advent calendars are nowadays part of the preparation for the feast of the birth of Jesus Christ in Christian countries .

In German-speaking countries, children in particular have an advent calendar. However, there are also those that are more aimed at adults. Calendars that are printed with Christmas motifs and on which small doors can be opened behind which there are pictures, sayings, sweets or other surprises are widespread in the trade. Self-made calendars are also used, which are often based on a similar principle.

Historical

Origins

Initially, the advent calendar was primarily a counting aid and a timepiece. The actual origins can be traced back to the 19th century; the first self-made Advent calendar probably dates back to 1851. The first forms came from the Protestant environment. Families gradually hung up 24 pictures on the wall. A variant with 24 chalk lines drawn on the wall or door, where the children were allowed to wipe away one line every day, was simpler. In Catholic households, however, straws were placed in a manger , one for each day until Christmas Eve . Other forms of the Advent calendar were the Christmas clock or an Advent candle, which was burned down every day until the next mark. This variant was particularly widespread during the National Socialist era as a replacement for the usual advent calendar. At the same time, burning down is a Scandinavian tradition.

In his novel Buddenbrooks, Thomas Mann mentions the Advent of 1869, in which little Hanno follows the approach of Christmas on a tear-off calendar made by the nurse:

"Under such circumstances this time Christmas was approaching, and with the help of the Advent calendar that Ida had made for him and on the last leaf of which a Christmas tree was drawn, little Johann followed with a throbbing heart the approach of the incomparable time."

1900 to the Second World War

In 1902 the Evangelische Buchhandlung Friedrich Trümpler in Hamburg published the first printed calendar in the form of a Christmas clock for children with the numbers 13 to 24 on the dial. From 1922 onwards, Christmas and Advent clocks with 24 fields appeared.

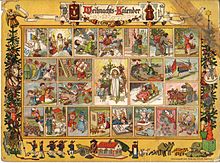

In 1903 the Munich publisher Gerhard Lang brought a printed calendar with the title Im Lande des Christkinds on the market. It consisted of a sheet with 24 pictures to cut out and a sheet with 24 fields to stick on. Every day during Advent the children were allowed to cut out a picture and paste it in a field. Since December 1st was a rather arbitrarily chosen date - the Advent season has between 22 and 28 days depending on the beginning, which means that December 1st was usually already in the Advent season - Lang first brought out a Santa Claus calendar from the following year, which began on December 6th. Such St. Nicholas calendars were also popular as promotional gifts at this time. Leipzig publishers also published such calendars. There were also Advent houses and Christmas clocks with the count from December 6th. After 1945, such calendars were rarely produced. In 1904, an advent calendar was enclosed with the Stuttgarter Neue Tagblatt as a present.

The 1920s are considered one of the weddings for the printed Advent calendar. They were often designed by well-known and less well-known children's book illustrators, poster artists or designers of greeting cards, coloring books, children's games and playing cards. Thus designed Gertrud Caspari a 1928 calendar published in Esslinger J.F. Schreiber Verlag , in Hamburg 1920 the Christmas calendar for our little ones by Johann Huber with texts by Hedda Krüss . In 1929 the Nuremberg art publisher Anton Jaser published two tear-off pads under the names Knecht Ruprecht and Weihnachts-Engel . Children could stick the tear-off pictures in an accompanying album. A year later a tear-off advent calendar was published in Hamburg. Another form were calendars designed as a ladder to heaven , on which one could move an angel one step further every day.

In the 1920s, the secular calendar ousted the religious from the top of the spread. The so-called “Erika calendars”, for example, often showed modern motifs such as modern means of transport from railways to cars to airplanes or traffic policemen, and primarily addressed a male audience. The pictures were mostly designed in a "lovely" style that some providers, such as the Dürerhaus movement , wanted to counteract with qualitatively and artistically more sophisticated products and at the same time wanted to contribute to artistic education. Successful calendars have been reissued over and over again over decades.

After 1920, calendars with small windows that could be opened became widespread. Behind every window there was a picture on a second, glued-on paper or cardboard layer. Until the 1930s, the Reichhold & Lang lithographic company in Munich enjoyed the reputation of publishing the most artistic and imaginative works in this field. Lang came up with the idea that every year in the run-up to Christmas, his mother sewed 24 pieces of biscuit (“ wibele ”) onto a box and as a child he was allowed to eat one every day from December 1st. Lang has also produced a kind of chocolate advent calendar, the Christkindinshaus for filling with chocolate . Other forms of ornament also came into fashion. Many of the calendars were covered with glittering materials. Initially, mostly potash mica ("cat silver") was used, but also metal sand ("scattered luster") or glass mica. Glass mica in particular was used until the 1970s, when it was replaced by harmless aluminum.

Saxony in particular was a center for the production of Advent calendars. In Leipzig, for example, the publishers Meissner & Buch , Josef Alzinger and Arthur Beyerlein Kunstverlag , in Dresden the publishing house Dürer-Haus and the Walter Flechsig publishing house , in Heidenau Erika , in Buchholz Herold , in Chemnitz and Halle / Saale the BFB publishing house . The rest of the production also had a focus in eastern Germany, for example in Berlin (Paul Pittius AG) , Zittau (Werner Klotz Verlag) , Magdeburg (Willy Klautzsch) or Reichenau (Rudolf Schneider Verlag) . On the other hand, there were regions in Germany where Advent calendars were unknown for a long time. Such calendars were apparently unknown in the border regions of the Sudetenland until 1938. Advent calendars have also been successfully sold in other countries. In addition to Austria, they have been successfully exported to England and by the Lahrer Verlag Ernst Kaufmann since before the First World War . Meissner & Buch from Leipzig provided their calendars with the addition Printed in Germany .

Pre-Christmas , the National Socialist Advent calendar

During the time of National Socialism , attempts were made to push Christian Christmas customs back from public life. As early as 1933, the change and the influence of the new era could be felt in some calendars. The Munich publisher Reichhold & Lang showed, among other things, a saluting soldier. This calendar with sliding figures designed by Dora Baum also had the title German Christmas . Calendars designed by Hertha Fritsche , published in 1936 and 1938, called December the Julmond and the Christmas festival Yule . But not all calendars were adapted to the new zeitgeist. CC Meinhold from Dresden, for example, published five different work folders based on designs by Max Noack between 1935 and 1937 , with which you could make your own calendars.

After 1940 the paper was allocated in Germany. Christmas calendars were only allowed to be printed on wood-containing paper and the maximum sizes and weights as well as the maximum thickness of paper and cardboard were specified by the Reich Office for Paper and Packaging . Christian publishers have had to publish other products since June 1941, which is why the publisher's last verifiable calendar appeared in 1940. This The Children's Advent Booklet lasted until December 25th and was provided with paper cuts and sayings.

After the outbreak of the Second World War , the main cultural office published a pre-Christmas calendar from 1941 in the Reich Propaganda Office of the NSDAP . The pre-Christmas calendar was designed by Thea Haupt and, in addition to a selection of fairy tales and National Socialist Christmas carols, also included baking instructions for what are known as pastries . The calendar from the central publishing house of the NSDAP Franz-Eher-Verlag was supplemented by handicraft instructions for wooden Christmas tree decorations in the form of runes and sun wheels , Klausen trees made of potatoes and so-called Christmas gardens, which were supposed to replace the cribs under the Christmas tree. The “derivation” of the meaning of runes and symbols as well as the so-called ancestral and clan research was also comprehensively addressed in the calendar. Christian symbols were reinterpreted as National Socialist symbols. After the 1941 calendar, which at first glance seemed harmless, was successfully tested in the families of functionaries with many children, it was put on the market from 1942 to 1944. With the changing situation on the front, the calendar, which at second glance was a clear propaganda product and clearly intended to indoctrine the youth, also increasingly received military content from 1942, which was graphically adapted to the respective military situation at the front. The practical living conditions are also reflected, so the baking recipes from 1943 onwards do without fat and eggs. Handicraft instructions showed things that could be made as thanks for soldiers who were asked to think about regularly. Obedience to the mother was also preached. The calendar was available centrally from the local groups of the NSDAP and had a nominal price of one Reichsmark.

Beyond the negative aspects, the pre-Christmas calendar was one of the first as a handicraft and hands-on calendar of this kind designed in book form. After the war it was listed on the index of publications to be segregated in the Soviet occupation zone. It was also initially banned in the West, but after the content was " denazified " in 1968, 1973 and 1982 it was reissued and is still distributed today.

Post-war until today

West Germany

Soon after World War II, the longing for an "ideal world" began, which also included the Christmas season. As early as 1945, Advent calendars were being produced again in all occupation zones. Above all, the sweet motifs from around 1930 were used here. Some publishers such as Erika in Heidenau reprinted their older works. Today, these calendars can often only be distinguished from the older copies because of the poorer paper and print quality after the war. The use of old templates was not least a cost factor. In addition, some of the designers who were active before the war continued to work in this area after the war. At first, tear-off calendars were particularly popular.

Richard Sellmer Verlag in Stuttgart received one of the first permits to print Advent calendars in December 1945 from the US occupiers. The permission to print 50,000 calendars could be covered by paper from the French occupation zone. In 1946, Richard Sellmer made the calendar designed by Elisabeth Lörcher , Die kleine Stadt, at home . He was represented with him at the Frankfurt trade fair and, last but not least, was looking for customers among the Americans. The very first calendar was designed internationally and was also made in English and Swedish. Marketing, which focused on international sales from the start, was obvious. Instructions for use in English and French have been included with the Alt-Stuttgart calendar since 1948 . Returning US soldiers ensured the spread and in 1953 Sellmer received a first major order for 50,000 calendars from an aid organization for epileptics. After a picture of Eisenhauer's grandson with an advent calendar appeared in Newsweek magazine in December 1953 , demand increased massively. For 1954, a White House calendar was produced with the White House as the central motif, surrounded by cowboys , covered wagons and road cruisers. Like the Fairy Tales calendar from the same year, this was produced especially for the US market in a version translated from German into English. Other producers followed this successful trend and the calendar craft house or Children Workshop of Ulla Wittkuhn showed two different motives for 24 December: for the German children a Christmas tree and Mary with the child, for the children in the United States a burning fireplace.

Sellmer-Verlag produced more than 230 different Advent calendars between 1946 and 1998 alone. The publishing house is now run as a family business in the third generation. By 2010 he had around 100 different motifs on offer every year. Many of the different calendars are explained by the different traditions of the countries for which they are made. For example, Santa Clauses are not used in Swiss calendars, angels have no wings in the USA and religious motifs are preferred in the UK.

Other publishers were also producing again from 1946. At first, tear-off calendars were widespread for a few years, but by 1950 they had largely been replaced by calendars with hinged doors. The Ars Sacra Verlag in Munich produced very loving and detailed calendars, the content of which always focused on the religious reference. Between 1954 and 1976 Gudrun Keussen in particular designed the approximately 30 calendars of the publisher. After the publisher was renamed to arsEdition in 1980 , the content also changed from religious to familiar. The Munich Korsch Verlag, founded in 1951, was also of importance . Calendars designed by East Germans such as Kurt Brandes or Fritz Baumgarten were printed here. In general, Korsch-Verlag bought many of its motifs from other publishers and still offers many of the older motifs to this day. Marketing strategies, such as the printing of company names, were also implemented at Korsch. To this day Korsch is one of the most important and successful publishers of its kind.

The most widespread form of the conventional Advent calendar today probably goes back to a Protestant pastor. He modified Lang's idea and hid pictures with characters from biblical stories behind 24 small doors . After 1945 the calendar finally prevailed, beginning December 1st with 24 doors. In addition, calendars with more doors were often produced, especially December 24th was always given more than one door, but the Sundays of Advent could also have additional windows, especially if they were outside the 24 days. A calendar designed by Paula Jordan with the title “The Secret of Christmas”, a so-called “Three Kings Calendar”, even lasted until January 6th. They were mainly offered by religious publishers and sold well into the 1960s.

The advent calendar became popular across the board from the 1950s, when it became a mass-produced item and was therefore offered at a reasonable price. The main motifs were scenes from romantic, snow-covered towns. A nativity scene is usually hidden behind the larger window on December 24th. Hand-painted advent calendars by various artists, such as the Leipzig advent calendars, also gained importance.

At present, behind the door of a purchased product, next to the pictures, there are often pieces of chocolate in various shapes or toys . The first chocolate-filled advent calendar was launched in 1958. In Germany in 2012, the Stiftung Warentest found mineral oils and related substances in the chocolate of various Advent calendars. The Federal Institute for Risk Assessment stated that mineral oils in food were undesirable, but estimated the intake from one piece of chocolate per day to be very low. In 2016, the Bavarian State Office for Health and Food Safety checked Advent calendars from manufacturers who had been noticed by mineral oil residues in the past year.

In addition, self-made calendars with small gifts are produced, which can be packed in different ways. A wide variety of shapes can be tinkered here: the jute bags, originally from the Scandinavian region, hung on a leash, are enjoying increasing popularity, but unusual ideas can also be implemented in self-made Advent calendars. Candles were also offered as advent calendars, with a section to burn down for each day. The world's largest free-standing Advent calendar with 857 m² is located in Leipzig in Böttchergässchen. The calendar doors are three by two meters and are opened daily.

The calendar motifs are generally timeless in order to ensure that the motifs can be used over a longer period of time. Motifs that go beyond this, such as the fall of the German Wall in 1989, are rare and cannot be sold over a long period of time.

Virtual advent calendar

For a few years now, new media have been increasingly used, for example to combine the original function of the Advent calendar, counting the days, with telling stories. There are audio books published 24 stories so that the listener can hear from December 1 to Christmas Eve, a story every day. Winter or Advent motifs and content predominate here, too, on name days such as St. Nicholas on December 6th, a legend is told or read aloud. Sometimes songs can be heard instead of stories. Advent calendars are also available on the Internet.

Advent calendar on television

In the Scandinavian countries it is a tradition that a 24-part Advent calendar (norw. Julekalender ) is broadcast on television at Christmas . It is an ongoing Christmas story with a section broadcast each day. An example of this is Schneewelt - a Christmas story ( orig.Snøfall ), which was also dubbed for KiKA and broadcast in 2018.

Buildings as an advent calendar

In several cities, the facades of certain buildings, often town halls , are regularly converted into large Advent calendars. A famous example of this is the Vienna City Hall , in front of which the Vienna Christmas Market takes place. A special tradition has developed in a number of towns and villages: On the days of Advent or December, you go to a shop window, barn door or something similar, where a “little door” has been designed and a story is read or told. In Meiningen , for example, such a narrative location is the city library, behind whose shutters there are colored fairy tale motifs.

In addition, a few years ago (around 2003) the “world's largest Advent calendar” was created in the Evangelical Church in Württemberg . Here every day in Advent another church in Württemberg opens its doors for an Advent day of action. In the Advent calendar of the city of Forchheim , the 24 doors are formed by the main gate and 23 windows of the half-timbered town hall. Christmas motifs are hidden behind the shutters, which are opened by the annually changing "Christmas Angels". The North Frisian town of Tönning claims to have the "longest Advent calendar in the world". The advent calendar extends over the 77.5 meter length of the building and the entire height of the listed old packing house, a former storage building at the Eiderhafen. The calendar doors from 1 to 24 are illuminated with the respective day number.

Lively advent calendar

In many parts of Austria, Germany and Switzerland, windows are decorated in the respective town during Advent or given a corresponding number for the number of the day and illuminated in the evening.

With the "living advent calendar", also known as the "walk-in advent calendar", people meet in front of a different house with an advent calendar window every Advent day. For this a window of the house is decorated for Advent. The twenty-fourth door illustrates the meaning of an Advent calendar, namely the arrival of Christmas Eve. At the individual stations, Christmas carols are sung in front of or in the house and Christmas stories are told. Culinary delights can also be offered. Such encounters often take place in ecumenical partnership between neighboring Catholic and Protestant communities. In Switzerland, this type of advent calendar is called “Advent calendar in the quarter” or “Advent window” and is usually organized by an association or a group of people, more rarely by a church.

Inverted advent calendar

The reverse Advent calendar has been propagated by some charitable institutions and churches since the mid-2010s: every day in Advent, a small donation (long-life food, hygiene articles, items of clothing, tickets for the local transport association, etc.) is placed in a box and this is done on the 24th Donated to a charity on December 12th (or in the days after). The inventor of this idea can probably no longer be clearly identified, but until 2018 various charitable institutions, for example in the Vienna area , had taken up and supported this suggestion.

literature

- Sandra Binder: When is Christmas finally? The story of the first advent calendar . Holzgerlingen, SCM Hänssler 2009, ISBN 978-3-7751-4899-3

- Esther Gajek : Advent calendar, from the beginning to the present . Süddeutscher Verlag, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7991-6422-7

- Alma Grüßhaber: meeting point windows . Design and celebrate the "Living Advent Calendar". Verl. Junge Gemeinde, Leinfelden-Echterdingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-7797-0537-6 .

- Münchner Bildungswerk (Ed.): Klaubauf, Klöpfeln, Kletzenbrot: The Munich Advent Calendar. Volk Verlag, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-86222-049-6 . (With numerous colored illustrations)

- Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. (= Museum of European Cultures - Series of publications , Volume 7) Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 .

- Werner Galler: Advent calendar. In: Christa Pieske: ABC of luxury paper, production, distribution and use 1860–1930. Museum for German Folklore, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-88609-123-6 , pp. 76–78.

Receipts and individual evidence

- ↑ ritual ( Memento of 2 December 2007 at the Internet Archive ) in the Arte telecast carom from December 4, 2005

- ↑ a b c History of the Advent Calendar ( Memento from January 19, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) - “Customs in Schleswig-Holstein”, December 14, 2007

- ↑ www.mainpost.de - “Memory trip with the advent calendar”, December 14, 2007

- ↑ Markus Mergenthaler (ed.): Advent calendar in the course of time . Knauf Museum, Dettelbach 2007 ( Google book ).

- ↑ The History of the Advent Calendar. ( Memento of April 9, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Sellmer Verlag, accessed on December 22, 2009

- ↑ a b c Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 26.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 27.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , pages 28-29.

- ↑ a b Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 31.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 23.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 33.

- ↑ a b Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 35.

- ↑ Esther Gajek: Advent Calendar: From the Beginning to the Present . Süddeutscher Verlag Munich 1996, ISBN 3-7991-6422-7 , pages 79 ff.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 36.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , pages 36–37.

- ↑ Judith Breuer, Rita Breuer : Because of Holy Night - Christmas in political propaganda. Verlag an der Ruhr, Mülheim an der Ruhr 2000, ISBN 3-86072-572-6 , pp. 77f.

- ↑ We bake for the festival . In: Hauptkulturamt der Reichspropagandaleitung der NSDAP: Vorweihnachten , Ed. Thea Haupt, F. Eher, Munich 1942, p. 13a.

- ↑ Of the symbols . In: Main Cultural Office of the Reich Propaganda Leadership of the NSDAP: Vorweihnachten , Ed. Thea Haupt, F. Eher, Munich 1942, p. 20a.

- ↑ The clan . In: Main Cultural Office of the Reich Propaganda Leadership of the NSDAP: Vorweihnachten, Ed. Thea Haupt, F. Eher, Munich 1942, p. 20.

- ↑ Judith Breuer, Rita Breuer: Because of Holy Night - Christmas in political propaganda. Verlag an der Ruhr, Mülheim an der Ruhr 2000, ISBN 3-86072-572-6 , pages 77f .; Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , pages 38–39.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 39.

- ↑ a b Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 40.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 38.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 41.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 44.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 47.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , pages 47-48.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 51.

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 52.

- ^ Anne-Christin Sievers: Christmas presents 24 times. Pictures and chocolate have had their day. Behind the doors of the new advent calendars are lipstick, Lego-Yoda and screwdrivers , Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, November 20, 2011, No. 46, p. 29

- ↑ Manfred Blechschmidt: Christmas customs in the Ore Mountains . Altis-Verlag, Friedrichsthal 2010, ISBN 978-3-910195-60-8 , p. 36

- ^ Stiftung Warentest, Advent calendar with chocolate filling: Mineral oil in chocolate , November 26, 2012

- ↑ Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, mineral oils in chocolate and other foods are undesirable , November 28, 2012

- ^ Mineral oil found in advent calendar chocolate , accessed on November 25, 2016

- ↑ Make your own advent calendar

- ^ Tina Peschel: Advent calendar. History and stories from 100 years. Verlag der Kunst, Husum 2009, ISBN 978-3-86530-114-7 , page 55.

- ↑ Store norske leksikon (Norwegian)

- ↑ Tönniger Christmas event

- ↑ Reverse Advent Calendar 2018 at Streetlife Vienna , accessed on April 28, 2019

- ↑ Reverse Advent calendar at Mobility Agency Vienna , accessed on April 28, 2019

- ↑ Reverse Advent Calendar 2018 of Volkshilfe Wien , accessed on April 28, 2019

See also

Web links

- Website of the association: Lebendige Adventskalender e. V. Accessed December 13, 2015 .