Nazi trials

The Nazi trials are, in a common short form, the criminal trials for crimes of National Socialism . In the specialist discourse, the short form NSG proceedings is widespread for proceedings on Nazi violent crimes . The everyday discourse also describes a part of it as war crimes trials .

overview

The legal prosecution of crimes committed during the Nazi era had been decided by the Allies during the course of the war and began immediately after the end of the Second World War . The Dachau trials before American military courts began on November 15, 1945 in the Dachau internment camp , on the site of the former Dachau concentration camp . It was discussed that prisoners of war had been mistreated and killed in the National Socialist concentration camps , including through human experiments . The Nuremberg Trials took place between November 20, 1945 and April 14, 1949 in the Nuremberg Palace of Justice . The introductory Nuremberg trial against the main war criminals took place in front of a specially established International Military Tribunal (IMT); the twelve subsequent trials, however, were carried out by US military courts. Until then, high-ranking military and government members of Germany and Austria , similarly to Japan , were charged with crimes against peace , crimes against humanity and war crimes , and mostly convicted. In doing so, the legal basis was created according to which tens of thousands of follow-up proceedings were carried out against subordinate individual perpetrators who were involved in crimes of various kinds under German occupation.

After just a few years, these follow-up processes were left to the national judiciary in many areas of the states on whose territories the respective crimes had taken place because they had been occupied or attacked by the German Empire and the Japanese Empire between 1939 and 1945 : These included Bulgaria , France , Greece , Great Britain , Yugoslavia , the Netherlands , Norway , Poland , Romania , the Soviet Union , Czechoslovakia and Hungary . Two separate cases, namely the Eichmann trial and the trial against John Demjanjuk , were carried out in Israel .

Most war criminals succeeded after the Second World War to escape with the help of the so-called rat lines and to avoid punishment. The escape routes led mainly to Argentina , but also to the countries of the Middle East . However, there is no precise information about the number of Nazi perpetrators who fled. Historians call the numbers from 180 to 800 National Socialists who emigrated to Argentina (as of 2010).

For Germany, to which most of the Nazi perpetrators belonged, the Allies decided to denazify . This should be a first step towards the criminal investigation of the Nazi era. For this purpose, the defendants were divided into "main culprits, incriminated, less incriminated, followers and non-incriminated". In the American zone of occupation, in particular, this meant that the mass of those who were less polluted and followers had to answer in front of the ruling chambers . The proceedings planned for later against the more heavily burdened were then hardly carried out. This approach met with increasing resistance in the German population (up to 70 percent according to a survey in 1949). The proceedings before the arbitration chambers were ended in the individual federal states in 1951/1952 .

Further Nazi trials have been carried out by the Federal Republic of Germany , the GDR and Austria since the 1950s : There they were an essential part of the legal and moral coming to terms with the past . The political circumstances, especially the Cold War , resulted in significant differences in the scope, intensity, legal basis, procedures and objectives of the other Nazi trials in the participating states.

Some Nazi crimes were not prosecuted at all or did not lead to adequate punishment of the perpetrators. The files produced during investigative procedures and trials form an important source of historical research on National Socialism. The United States had already begun to German scientists and technicians of the Second World War in 1945 at the end of recruit and to secure their military technical skill and knowledge, making them ultimately prosecution were revoked.

Allied resolutions to prosecute Nazi criminals

Since 1942 the Allies have repeatedly publicly declared their determination to punish the Nazi criminals, especially those responsible for the war and the extermination of the Jews.

On January 13, 1942, representatives of the occupied states of Belgium, France, Greece, Yugoslavia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland and Czechoslovakia gathered in the St. James Palace in London. China, Great Britain, the USSR and the USA sent observers. The occupied states demanded that the punishment of the crimes of occupation perpetrated against their citizens should be declared one of the main Allied war aims and vowed in the St. James Palace Declaration , “to ensure that in the spirit of international solidarity

- those guilty or responsible persons, regardless of their nationality, are tracked down, handed over to the judiciary and tried

- the pronounced judgments are carried out "

This declaration was later also joined by China and the USSR. The constant pressure from the governments-in-exile of the occupied states led the British Foreign Office, together with representatives of the USA , to decide in October 1942 to found the United Nations Commission for the Investigation of War Crimes (UNWCC) to collect evidence of war crimes committed by the Axis powers . This institution, which began operating in October 1943 as the United Nations War Crimes Commission , was founded before the UN . It had no executive powers, but reported to the nations that later belonged to the UNO until 1949 about war crimes of the Second World War, which their governments then pursued at their own discretion.

In the Moscow Declaration of the Three Powers , Great Britain, the USA and the Soviet Union agreed on November 1, 1943, to bring the main war criminals, whose responsibility was not geographically limited to one country, to central international criminal courts. Otherwise, war criminals should be brought to justice in the countries in which they had committed their crimes. Furthermore, the global tracking down, detention and extradition of suspected Nazi criminals was agreed.

The Potsdam Agreement provided for Nazi war criminals to be tried in Allied courts in their respective zones of occupation. The agreement, which the Allies signed on August 8, 1945 in the Cecilienhof Palace in Potsdam, formulated the Charter of the International Military Tribunal (IMT), the London Statute . This IMT charter formed the foundation of this court. It explained the purpose, laid down the procedure for the criminal proceedings and determined the individual charges.

On December 20, 1945, the Allied Control Council of the four victorious powers passed Control Council Act No. 10 , which established a uniform procedure for the punishment of National Socialist crimes. After that, the commanders of the four German occupation zones were allowed to conduct criminal trials on their own for warlike aggression, violation of martial law, crimes against humanity and membership in corresponding organizations. The Allied military courts, however, have mostly limited themselves to prosecuting acts of which their own nationals and those of their allies were victims.

Jurisdiction

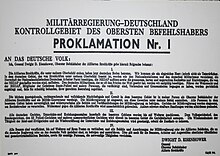

When the Allied troops marched into Germany, all German courts were closed on the basis of Art. III of Proclamation No. 1 of the Allied Commander-in-Chief. The administration of justice stood still. It was not until the second half of 1945 that the courts resumed their activities at different times locally.

The reopening of the courts was legalized by Control Council Act No. 4 of October 30, 1945 on the Reorganization of the German Judiciary and Act No. 2 of the American Military Government. However, the competences of the German courts were restricted by Art. III of the Control Council Act No. 4. In particular, German courts were not allowed to judge any criminal acts that were committed by National Socialists or other persons against nationals of Allied nations or their allies without special authorization.

For the trial of the crimes of the National Socialist regime, the Allies initially claimed exclusive jurisdiction. Art. II No. 1 a, b, c of Control Council Act No. 10 of December 20, 1945 criminalized crimes against peace , war crimes and crimes against humanity . Art. III No. 1 d sentence 1 of the same law gave the occupation authorities the right to bring the persons charged with trial to a suitable court. However, the occupation authorities were able to declare German courts responsible for the trial of crimes that German nationals had committed against other German nationals or stateless persons.

In the American zone , this authorization was granted on a case-by-case basis; in the British and French zones , general authorizations were issued.

Art. 14, 15 of Act No. 13 of the Allied High Commission of November 25, 1949, with effect from January 1, 1950, the Control Council Act No. 4 was suspended. The regulations that limited the jurisdiction of the German courts in criminal matters were repealed except for a few reserved rights of the occupying powers.

According to Part I, Art. 3, Paragraph 3, Letter b of the Treaty on the Regulation of War and Occupation Issues ( transition agreement in the version of the notice of March 30, 1955), the acts on which the proceedings are based could be taken by the courts and public prosecutors in the Federal Republic Germany will no longer be prosecuted if one of the three western occupying powers has already conducted and finally concluded criminal investigations.

Allied trials in Germany

Nuremberg Trial of Major War Criminals

The International Military Tribunal resulted chaired by judges of all four victorious powers from 1 October 1945 to 18 October 1946 Nuremberg trial of the major war criminals by, were charged in the 24 German and Austrian major war criminals. 22 defendants were sentenced, including 12 to death by hanging.

The indictment originally comprised four items: joint plan to commit war crimes (conspiracy), crimes against peace (especially preparing for a war of aggression ), war crimes and crimes against humanity . This was the first time in history an attempt was made to hold the leaders of a war-inducing regime and its army liable for crimes committed in the context of their politics, war planning and warfare . According to the statute of the IMT, these charges were directed against all leaders, organizations, instigators and assistants of such crimes, including those who had not committed them personally, but were involved in the decision, in their planning, appointment and organization.

The charge of arranging to commit war crimes was not specifically pursued in the course of the proceedings; it was subsumed under the Crimes Against Peace Charge . So that all those indirectly involved in such crimes could be prosecuted without having to prove their own crimes in separate proceedings, the IMT declared the organizations of the NSDAP , SS and Gestapo to be criminal organizations. The members of the SD and Gestapo who were involved in purely administrative tasks, as well as lower-ranking officials of the NSDAP and the Waffen SS , were excluded from a blanket charge .

The first Nuremberg Trial was followed internationally as in Germany itself with great media interest and intensive participation and discussion of the public. The majority of the German public approved it - which could also be interpreted as an exoneration of one's own fault. The process remained present in the collective memory. In attempting to denounce it as “ victorious justice ”, the political right in Germany and Austria separated from the majority. Obvious conflict between the victorious powers, as based on the interpretation of the Katyn massacre, contributed more to the acceptance of the procedure.

Processes in the individual occupation zones

According to the Control Council Act No. 10 , further criminal trials took place in the individual zones of occupation following the Nuremberg trial of the main war criminals. In addition, there were the arbitration chamber proceedings , which did not serve to punish, but to purge ideologically from National Socialism .

American zone of occupation

In the American occupation zone , from December 1946 to April 1949, twelve follow-up trials took place in the Nuremberg Palace of Justice against 177 other high-ranking representatives of the German Reich , including leading members of the Reich Ministries, Gestapo, SS, Wehrmacht, civil servants in the judiciary and medical administration Industrial. The judges this time were 30 civil US lawyers, as well as the approximately 100 prosecutors, both mostly from the US state supreme courts. The defense attorneys were 200 mostly German lawyers.

British zone of occupation

In the British occupation zone , military courts negotiated on the basis of the Royal Warrant (Royal Decree) of June 14, 1945. The so-called Curiohaus trials took place in Hamburg.

French zone of occupation

Military trials were held in the French occupation zone before the Tribunal Général in Rastatt. From September 1948, the Tribunal de première instance pour les crimes de guerre took over this task.

Soviet occupation zone

In the Soviet occupation zone, the proceedings were directly subordinate to the Soviet secret service NKVD . According to official Soviet information, around 122,600 people were imprisoned, plus a further 34,700 of foreign, predominantly Soviet nationality, who were in Germany as foreign or forced laborers . The total number of those convicted there is estimated at 45,000, about a third of whom were deported to forced labor, most of the rest were held in special camps. The number of death sentences is unknown.

Totals

In total, around 50,000 to 60,000 people were convicted of Nazi crimes by the courts of the victorious powers in Germany and other countries.

In the three western zones , Allied military courts sentenced a total of 5025 German defendants. Death sentences were pronounced in 806 cases , of which 486 were carried out.

Contemporary rating

The subsequent trials of the victorious powers were increasingly interpreted in Germany as victorious justice . High-ranking church representatives, influential party politicians and other exposed personalities vehemently demanded an amnesty for the war criminals and Nazi perpetrators incarcerated in the allied prisons of Landsberg (USA), Werl (UK) and Wittlich (France) . Spokesmen among the parliamentarians in West Germany were the parliamentary groups of the FDP and the German party . While they demanded an immediate revision of the judgments and the indiscriminate release, the first Federal Minister of Justice, Thomas Dehler (FDP), advocated a gradual amnesty.

In the late 1940s, the western allies changed their policy towards Germany because of the Cold War. The convicted perpetrators still incarcerated in Landsberg were executed or, in the majority of cases, released. In connection with rearmament and the Korean War , the American High Commissioner John J. McCloy gradually gave in to the demand for the condemned to be released, pardoned almost all those sentenced to death, reduced prison terms by a third and released celebrities such as Friedrich Flick and Ernst von Weizsäcker in 1950/51 and Alfried Krupp from prison. This had a social signal effect in West Germany. The actual criminals were now considered to have been tried and further criminal proceedings to be inappropriate.

Of the prisoners brought together in Landsberg, the last four were released in 1958, including three Einsatzgruppenführer originally sentenced to death . After that, only those convicted from the first Nuremberg trial were in custody, for whom there was no pardon due to the Soviet veto - Rudolf Hess was the last until his death in 1987 in the Spandau war crimes prison ( Berlin ).

consequences

The Nuremberg Trials produced a number of lawyers whose revisionist defense strategies strongly influenced the attitudes of sections of the population, and not only in Germany. In 1994 the Canadian Supreme Court issued a judgment in a review process in which the Holocaust was denied as organized, racially justified mass extermination and the persecution of the Jews was placed in the context of the war. Anti-Semitic propaganda was accepted as a reason for state authorities such as the police to participate in the mass murder .

German jurisdiction

Federal Republic of Germany

While the Nuremberg Trials of the Allies primarily brought those primarily responsible and desk perpetrators in ministries and administrations to justice, West German criminal prosecution was initially directed primarily against those who had perpetrated the National Socialist terror themselves. Violent crimes were now the focus.

Processes according to the Control Council Act

Article III of Control Council Act No. 10 provided, among other things:

"The occupation authorities can declare German courts responsible for the trial of crimes committed by German citizens or nationals."

German courts could initially only initiate criminal proceedings with the consent of the occupation authorities of the respective zone, and only against Germans who had committed crimes against other Germans or stateless persons. This authorization was granted in the British and French occupation zones in general, and in the Soviet zone in individual cases. No such authorization was given in the American zone. Only the German penal code was used in the prosecution of Nazi crimes by German courts.

Until the Allied authorization was withdrawn in 1951, 1,865 people had been indicted and 620 convicted by German courts on the basis of the Control Council Act and German criminal law. Most of these judgments concerned less serious crimes such as denunciations, bodily harm, deprivation of liberty and coercion. Homicides were prosecuted as part of criminal proceedings against concentration camp personnel, those involved in euthanasia, and executions or murders of soldiers and civilians who had refused to serve any further militarily senseless military service in the “final phase” of the last weeks of the war. Almost all of these proceedings came about through reports from victims or their relatives against known or accidentally discovered perpetrators.

The German criminal lawyers mostly preferred their own judicial tradition and used violent crimes under the German Criminal Code. In addition, in May 1946, the US military government ordered the states in its zone of occupation (Bavaria, Württemberg-Baden, Greater Hesse) to pass laws to punish National Socialist crimes . These expressly provided that criminal prosecution would not be hindered by the fact that the act was at any time declared to be legal by a law, ordinance, decree or [..] .

However, the federal amnesty of 1949 and the Second Impunity Act of July 1954 amnestied not only offenses such as black market crimes, but - intentionally or unintentionally - also many perpetrators of the November pogroms of 1938 and most of the final phase crimes of the war. The number of preliminary investigations into Nazi crimes fell from around 1,950 in 1950 to 162 in 1954. In the following five years, a total of only 101 people were convicted.

The Control Council Act No. 10 was formally repealed in 1956, but it was no longer actually applied on August 31, 1951 after the Federal Ministry of Justice had withdrawn the Allied authorizations due to legal concerns. Since then, no proceedings have been opened or judgments made on this basis. From now on, only the Federal German Criminal Code was authoritative, which, however, according to the prevailing legal opinion, could not be applied retrospectively and was therefore only suitable to a limited extent for the prosecution of Nazi crimes.

Trials after 1957

Criminal prosecution received new impetus when the GDR used propaganda campaigns from 1957 to disseminate incriminating material against West German judges and officials. This made the public aware of the high level of personal continuity in the West German judicial service. However, not a single judge could because of violation of the law be convicted because the Federal Court to the necessary for this proof of intent set exceptionally high requirements. The proceedings against the chamber judge Hans-Joachim Rehse , who participated in numerous death sentences of the People's Court , can be regarded as an example of the failure of these trials .

In 1957/58 the mass murder of Jews in the Baltic States was examined in detail for the first time in the Ulm Einsatzgruppen trial . The first major trial against National Socialist perpetrators before a German criminal court aroused extraordinary public interest, as it became clear that this was just one example of a large number of Nazi crimes that had not yet been investigated. At the end of 1958, the state ministers of justice founded the Ludwigsburg Central Office , which was supposed to investigate Nazi crimes, but not war crimes. Numerous lawsuits were triggered by their preliminary investigations.

Because war crimes of the Second World War were effectively excluded from legal investigation in West Germany from 1958 onwards, the German Nazi trials primarily involved killing crimes against civilians that were committed outside of combat operations and combat areas. The focus was on the crimes in concentration camps, forced labor camps and ghettos, as well as the murders committed by the Einsatzkommandos and Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD . The distinction between the two crimes "Nazi crimes" and "war crimes", which was decided by the state justice ministers in 1958 when the Ludwigsburg Central Office was founded, aimed at the ideologically justified extermination actions, i.e. the murder of European Jews as well as the Sinti and Roma to solve, but not the crimes of the Wehrmacht , for example the planned starvation of millions of Soviet prisoners of war.

In 1960 the legislature allowed the statute of limitations for crimes such as bodily harm resulting in death to pass unhindered. The statute of limitations for murder was later extended several times by the Bundestag and finally lifted entirely in 1979.

From 1963 onwards, the Auschwitz trials took place against the camp crews at this extermination camp. Attorney General Fritz Bauer played the decisive role in this context, against massive resistance . The process was reported in many media. Details of how the media and the public were dealt with at the time are documented in the modern era in the exhibition at the Fritz Bauer Institute . The big statute of limitations debate in the German Bundestag on March 10, 1965 was perceived as a great moment in parliament and was intended to enable further criminal prosecution of as yet undiscovered perpetrators. In an opinion poll among the population, a slim majority had previously voted for an end to all processes.

With effect from October 1, 1968, Section 50 of the Criminal Code was amended with Art. 1 No. 6 of the Introductory Act to the Law on Administrative Offenses , which since then has provided for an obligatory reduction in penalties for aiding and abetting if the "assistants" did not share the low motives of the main perpetrators. This inconspicuous change had a major impact: Since the judiciary only pronounced guilty verdicts for “complicity in murder” in most cases of Nazi crimes and the accused usually denied their own “low motives”, they were now only subject to a reduced penalty range of 3 to 15 years in prison - which meant that the acts were statute barred since 1960, as the Federal Court of Justice decided in a sensational and controversial judgment on May 20, 1969. Investigations against 730 “desk perpetrators” of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), which were already well advanced , have now been discontinued due to the statute of limitations. This turn, often called a "glitch" in contemporary debates is very controversial in the legal history and historical debate today: Was it really a breakdown or walked the mishap on deliberate manipulation of former Nazis, especially Eduard Dreher , the Federal Ministry of Justice back - Or was this series of statutes of limitations mainly due to the political will and the positioning of the jurisprudence itself?

Processes in the 21st Century

There are also follow-up processes in the 21st century . The case law first abandoned the concrete evidence of individual offenses required for a conviction for aiding and abetting murder with the final conviction of John Demjanjuk in 2011 and Oskar Gröning in 2016. The joint plaintiffs welcomed this as an "important correction of the previous case law". With them, SS guards were sentenced for the first time in recent legal history, although they themselves had not murdered. In 2017, the Central Office for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes concluded an investigation against ten alleged concentration camp employees. In November 2017, the Dortmund public prosecutor brought charges against two former SS guards at the Stutthof concentration camp . A former SS man from the Majdanek concentration camp is charged in Frankfurt am Main, and a former security guard in the Auschwitz concentration camp in Munich. The Osnabrück public prosecutor's office is investigating the case of a 94-year-old who is said to have been involved in the murder of more than 33,700 Jews in Babyn Yar near Kiev. In Celle, the public prosecutor's office is examining the charges against a former dog handler in Auschwitz, and in Hamburg the use of a 91-year-old in the Stutthof concentration camp is being examined. In Itzehoe, Munich, Lübeck and Stuttgart there are investigations against four women who also served in Stutthof.

Totals

According to the latest research results, the following results emerged for the criminal prosecution of Nazi crimes by the German judiciary in the western occupation zones and the Federal Republic of Germany (including West Berlin and Saarland):

Between May 8, 1945 and the end of 2005, the public prosecutor's offices initiated investigations into 36,393 cases against 172,294 suspects. Of 16,740 defendants, 6656 were convicted, including those

- 16 to death (4 of them executed),

- 166 to life imprisonment,

- 6,297 on time-limited imprisonment,

- 130 to fine and

- 47 apart from punishment / unknown punishments.

The high number of accused was partly due to the fact that the public prosecutor's offices formally accused entire departments and units of the Wehrmacht , whose members were considered to be involved in the crime. This seemed necessary in order to avert an impending statute of limitations as a precaution .

The maximum sentence was imposed in 182 cases. In the majority of cases, the defendants were not convicted as perpetrators of their own volition, even in homicides, but only found guilty of aiding and abetting.

In the meantime, the prosecution for biological reasons, death or incapacity to stand trial of the accused, deceased witnesses etc. is coming to an end. However, several investigations are still ongoing and there are still cases in which legal proceedings are taking place.

German Democratic Republic

In the Soviet Zone , proceedings were already taking place in German courts parallel to the secret Soviet military tribunals, which were carried out in accordance with the Control Council Act No. 10 and the state's own laws. They were coordinated by a working group on Nazi crimes in the administration of justice.

In August 1947, the Soviet military administration ordered the interior ministries of the five states of the Soviet Zone to investigate further Nazi crimes. In February 1948 she ordered the Nazi trials that had been initiated to be concluded. By 1949, East German courts sentenced 8,055 people for Nazi crimes, almost all of which had taken place in the Soviet Zone. B. in the Radeberg concentration camp or during the “euthanasia” campaign T4 . 3,115 accused were convicted of mass crimes, 2,426 of denunciations, 901 of membership in Nazi organizations and 147 of judicial crimes.

In 1950 the Soviet occupation authorities closed the last internment camps in the GDR and handed over 3,400 prisoners as well as the full authority to prosecute Nazi perpetrators to the GDR judiciary. Those interned since 1945 were convicted in the so-called Waldheim trials that same year . 33 death sentences were passed, of which 24 were carried out. According to current knowledge, not all of the convicted were Nazi perpetrators.

By 1956, the number of convicted Nazi perpetrators in the GDR had sunk to zero. In the 1960s there were some spectacular accusations in absentia against former NSDAP members who had risen to state and government offices in the Federal Republic: for example against Theodor Oberländer in 1960 and Hans Globke in 1963. This turned state anti-fascism propagandistically against the Federal Republic. The 1966 trial of Horst Fischer , camp doctor in Auschwitz-Monowitz, caused a particular stir .

With the law on the non- statute of limitations for Nazi and war crimes of September 1, 1964, it was determined that the statutes of limitations of general criminal law do not apply to persons who “ committed crimes against the “ between January 30, 1933 and May 8, 1945 Peace that have committed, commanded or promoted humanity or war crimes. "

In 1968 a major criminal law reform in the GDR comprehensively defined all criminal offenses for Nazi crimes. Until the turn of 1989 , further Nazi trials were officially carried out against around 10,000 people - in addition to the 3,000 Waldheim judgments of 1950.

After German reunification in 1990, the perpetrators who were wrongly convicted in the Waldheim trials were rehabilitated; the death sentences passed there were overturned, and some of the GDR judges involved were initiated for perversion of justice.

Belgium

On June 20, 1947, Belgium passed a law giving military justice jurisdiction over war crimes. 75 Germans were brought to justice in Belgian military courts .

Bulgaria

Bulgaria sentenced 11,122 nationals, 2,730 of them to death. Germans suspected of participating in war crimes and crimes against humanity are said to have been extradited to the Soviet Union. The ordinance of 6 October 1944 on the sentencing of those responsible for Bulgaria's entry into the World War against the Allied Nations and for the crimes connected with it was directed exclusively against Bulgarians.

Denmark

In Denmark, 14,049 people were sentenced to prison terms for collaborating with Germans. 78 death sentences were passed, of which 46 were carried out. Approximately 13,500 were convicted of treason . The Danish treason law was passed by the Danish Reichstag in the summer of 1945. It applied retroactively from April 9, 1940, the first day of the German occupation of Denmark. Of these 13,500 people, around 7,500 were convicted of military collaboration. They had fought in the Frikorps Danmark or in other military units on the German side, and many had also participated in German guard or anti-sabotage corps. 2000 had served in the German police, 1100 were convicted of denunciation, murder, torture or other acts of violence. Because of high treason some leaders of the Danish Nazi Party were DNSAP sentenced, but the membership itself was not punishable. However, about 600 local or state officials were fired for membership of the DNSAP. About 1100 people were convicted of economic collaboration, and 318 million crowns were confiscated. In addition, 80 Germans were convicted, among them Werner Best , Hermann von Hanneken , Günther Pancke and Otto Bovensiepen in 1948 in the "big" war crimes trial .

France

On August 28, 1944, an ordinance on the punishment of war crimes was passed, which was supplemented by a law of September 15, 1948. On December 26, 1964, Law No. 64/1326 declared crimes against humanity non-statute-barred.

The exact number of convictions is unclear: in some cases 10,519 executions are given, of which only 850 were due to a court judgment; other sources assume 4,783 death sentences (around 2,000 executed) and 50,000 prison terms. In a second phase, various commissions for purification / cleaning / cleaning should not only check the police service for its actions during the Vichy period and collaboration in general in a somewhat legally comprehensible manner.

War crimes committed by members of the Waffen SS or the Wehrmacht who signed up to the Foreign Legion were not pursued any further.

Great Britain

The first British military trials were based on a Royal Warrant of January 14, 1945.

Israel

In Israel , the Knesset passed the Nazis and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law in 1950 . It was based on the London Statute and the Criminal Code Ordinance (CCO) of 1936. On the basis of this Israeli law, Adolf Eichmann , former head of the Jewish Department in the Reich Security Main Office , was sentenced to death in a trial in the Jerusalem District Court in 1961 and executed in 1962.

Italy

Japan

In Japan, following the example of the Nuremberg Trials of Major War Criminals, the Tokyo trials against military and political leaders of Japan took place before a multinational military court of eleven judges.

Yugoslavia and Albania

Yugoslavia and Albania have not published statistics on criminal cases. But even before the Nuremberg succession trial against the generals in south-eastern Europe , 19 German generals were executed in Yugoslavia. As early as 1946, extraditions of suspected war criminals were severely restricted by the Western Allies after concerns arose as to whether they would receive a fair trial.

Luxembourg

The Luxembourg judiciary opened court proceedings against 162 Reich Germans and there were 44 death sentences, 15 acquittals and 103 closings. Gustav Simon , the former head of the Luxembourg CdZ area, evaded charge by suicide in 1945 . His deputy Heinrich Christian Siekmeier was sentenced to seven years in prison. In 5,242 cases, Luxembourg courts gave rulings on collaboration cases, including 12 death sentences and the like. a. against the former chairman of the Volksdeutsche movement Damian Kratzenberg .

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, 35,615 people were convicted of collaborating with Germans. Of around 200 death sentences, 38 were carried out. There were also 204 judgments against Germans.

Norway

Immediately after the war, proceedings were opened against 92,805 Norwegians, mainly for treason. 46,085 people were punished, 28,919 of them with fines and loss of rights, 17,136 with imprisonment. 30 people were sentenced to death and 25 death sentences were carried out. According to a list by the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Police, the penalties were in

- 1,971 cases held in the Norwegian administration

- 7,146 cases activities in organizations and branches of the Norwegian fascist party Nasjonal Samling (NS)

- 2,784 cases of propaganda for the NS or for participation in the war on the German side

- 9,649 cases belonging to the Hird , the SA of the NS, and to the armed Hird departments, the Germanic SS and similar organizations

- 4,816 cases of war participation on the German side, including as a nurse for the German Red Cross

- 1,295 cases belonging to the German Security Police ( Sipo ) as well as to the Norwegian State and Border Police

- 1,043 cases of involvement in acts of murder and violence

- 4,765 cases of informing and informing people for the Sipo

- 290 cases of espionage and defense activity for the occupying power

- 3,208 cases of "economic treason"

- 5,014 cases work in German offices, companies and institutions

- 40,072 cases belonging to NS and affiliated organizations

- 1,907 cases of treason in other forms or other criminal acts

In addition, 80 Germans were convicted in Norway.

Austria

In Austria 13,625 own citizens were convicted. Legislation on war crimes and crimes against humanity has been amended several times; the first prohibition law dates from May 8, 1945. It was last amended in 1992 and is still in force today. On June 26, 1945, a constitutional law ... on war crimes and other national socialist crimes (war criminals law) was passed, which was repealed in 1957.

Poland

In Poland, a total of 5,385 Germans and Austrians were convicted of having committed National Socialist crimes. More than one in three of the German Nazi perpetrators convicted in Poland has been transferred there by the four occupying powers, mostly from the American occupation zone.

War crimes and crimes against humanity were criminal offenses in Poland according to the “Decree on the sentencing of the fascist-Nazi criminals guilty of murder and mistreatment of the civilian population and prisoners of war, as well as the traitors of the Polish people of August 31 1944 ”, amended and supplemented on January 22nd and June 28th, 1946 and on April 3rd, 1948.

Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union, the legal basis for prosecuting Nazi perpetrators was created in 1941. This was announced in many so-called Molotov notes. On November 2, 1942, the Extraordinary State Commission to investigate the crimes of the German-fascist occupiers was founded. This lasted until 1948. The Soviet Union did not join the United Nations War Crimes Commission .

Nazi trials were carried out in the SU according to the military criminal law of the individual republics. The war criminals decree of April 19, 1943 defined the penalties more precisely. In July 1943, the first Nazi trial ever took place in Krasnodar on this basis: This trial against Soviet helpers from Sonderkommando 10a made the use of German gas vans for mass murders internationally known. In December 1943 a trial of three German and one Soviet defendants followed in Kharkov . Almost all of the defendants in both of the trials accompanied by propaganda were sentenced to death.

An unknown number of trials followed by 1950 against local citizens accused of collaborating, German prisoners of war and suspected Nazi criminals extradited by the Western powers. The NKGB , from 1946 MGB, conducted the secret investigations while the proceedings were taking place before the NKVD and MVD courts.

At the end of 1945 a series of trials began against high-ranking SS and Wehrmacht leaders, u. a. in Minsk and Riga , including against Friedrich Jeckeln . This series lasted until 1948. From 1949 onwards, many rapid proceedings followed, especially against German prisoners of war, low Nazi ranks and suspected collaborators. The latter were often convicted of treason and “counterrevolution” without the rule of law and without guarantee of appeal, after the temporary abolition of the death penalty mostly to 25 years of forced labor.

Czechoslovakia

On June 19, 1945, the President issued a decree on the punishment of Nazi criminals, traitors and their accomplices and on extraordinary people's courts , which was made into law on January 24, 1946. It expired on December 31, 1948, after which general criminal law norms became the basis for further convictions. The number of Germans convicted in Czechoslovakia is estimated at around fifty percent of the 33,463 convicted Nazi perpetrators.

Hungary

Since 1945, Hungary has sentenced over 19,000 of 40,000 people accused of Nazi criminals and collaborators on the basis of Ordinance No. 81/45 on People's Justice, War Crimes and Offenses against the People . 380 death sentences were passed. It is not known how many convicts were Germans or Austrians.

The provisional government of Hungary began prosecuting Nazi perpetrators in December 1944 and immediately after the end of the war set up special courts - known as “people's tribunals” - for their proceedings. These have been accelerated since the Hungarian Communist Party came to power . By the end of 1946, the special courts condemned most of the Hungarian politicians who had cooperated with the German Reich or who had prepared this cooperation.

The trial against László Bárdossy , who, as Prime Minister of Hungary 1941–1942, had enforced his declaration of war on the Soviet Union, was exemplary of the Hungarian proceedings . He was found guilty of violating the constitution and of participating in the murders of Jews in Kamenets-Podolsk and Novi Sad and was hanged on January 10, 1946.

The death sentences of Márton Zöldy and József Grassy , who were involved in the Novi Sad massacre , were overturned by an appeals court. But after their later extradition to Yugoslavia, on whose territory the massacre had taken place, they were sentenced to death again and executed there.

On March 1, 1946, Bardossy's predecessor, Béla Imrédy, was also executed: as Prime Minister of Hungary from 1938 to 1939 he had prepared two anti-Jewish laws and signed the second. But he was rehabilitated after 1989.

Most of the members of the government in the cabinets of Döme Sztójay and Ferenc Szálasi were also executed in March / April 1946: including Andor Jaross , the former interior minister, and two of his state secretaries. You had been in charge of the deportations of Hungarian Jews. Emil Kovacs, leader of the Arrow Cross , Peter Hain, head of the Hungarian secret police and German agent, and László Ferenczy were also executed by the gendarmerie for proven involvement .

In 1967 other Arrow Cross members were charged. 16 of them were sentenced to long-term forced labor, Vilmos Kroszl , Lajos Németh and Alajos Sándor were executed.

See also

- Repeal of Nazi injustice judgments

- Victims of Nazi military justice

- Crimes of the Wehrmacht # prosecution

literature

- Federal Minister of Justice (Ed.): In the name of the German people. Justice and National Socialism - Catalog for the exhibition. Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-8046-8731-8 .

- Jürgen Finger, Sven Keller, Andreas Wirsching: From Law to History. Files from Nazi trials as sources of contemporary history. Göttingen 2009, ISBN 3-525-35500-9 .

- Norbert Frei : Politics of the past. The beginnings of the Federal Republic and the Nazi past. Munich 1999, ISBN 3-423-30720-X .

- Norbert Frei (ed.): Transnational politics of the past. How to deal with German war crimes in Europe after the Second World War, Göttingen 2006.

- Jörg Friedrich : The cold amnesty. Nazi perpetrators in the Federal Republic. Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-596-24308-4 .

- Jörg Friedrich: acquittal for the Nazi judiciary. The judgments against Nazi judges since 1948. Documentation. New edition. Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-548-26532-4 .

- Kerstin Freudiger: The legal processing of Nazi crimes. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-16-147687-5 .

- Andreas Kunz: Nazi violent crimes, perpetrators and prosecution. The documents of the Central Office of the State Justice Administrations in Ludwigsburg , in: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History 4 (2007), pp. 233–245.

- Jörg Osterloh, Clemens Vollnhals (Ed.): Nazi trials and the German public. Occupation, early Federal Republic and GDR (= writings of the Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarian Research . Vol. 45). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-525-36921-0 .

- Joachim Perels , Rolf Pohl (ed.): Nazi perpetrators in German society. Hanover 2002.

- Adalbert Rückerl : Nazi crimes in court. Attempt to come to terms with the past. Heidelberg 1982.

- Adalbert Rückerl: Nazi trials. After 25 years of prosecution: possibilities, limits, results. Müller, 1984, ISBN 3-7880-2015-6 .

- Adalbert Rückerl (Ed.): National Socialist Extermination Camps in the Mirror of German Criminal Trials. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Chelmno. dtv 2904, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-42302904-8 . (documents excerpts from court judgments and important witness statements).

- Christiaan F. Rüter , Dick W. de Mildt (ed.): Justice and Nazi crimes . Collection of German criminal convictions for Nazi homicide crimes 1945–1965. Volume I-XXII. Amsterdam 1968 ff.

- Gerd R. Ueberschär (Ed.): The National Socialism in front of the court. The allied trials of war criminals and soldiers 1943–1952. 2nd Edition. Fischer, ISBN 3-596-13589-3 .

- Günther Wieland : Judicial punishment of occupation crimes. In: Werner Röhr (Ed.): Europe under the swastika. Analyzes, sources, registers. Volume 8. Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-7785-2338-4 .

- Heiner Lichtenstein , Otto R. Romberg (Hrsg.): Perpetrator victim consequences. ISBN 3-89331231-5 .

- Helge Grabitz u. a. (Ed.): The normality of crime. Festschrift for Wolfgang Scheffler. Ed. Hentrich, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-89468-142-X (Part 3: The prosecution of National Socialist violent crimes. Part 4: Overview of the expert work and directory of the writings of Wolfgang Scheffler. Pp. 299-531).

- Nathan Stoltzfus, Henry Friedlander (Ed.): Nazi Crimes and the Law . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 978-0-5218-9974-1 (Publications of the German Historical Institute).

Web links

- Justice and Nazi crimes by Expostfacto with alphabetical listing and Google map

- private page on the Amnesty Act of December 31, 1949 .

- Franziska Augstein: Prosecution of Nazi criminals. In Süddeutsche Zeitung from October 22, 2008

- Winfried Garscha : Austria - the worse Germany? Subtitle: Facts and legends on Austria's relationship to the “Third Reich” before and after 1938 and on the Nazi crimes and their coming to terms with after 1945. Lecture in the Royal Library in Brussels on April 5, 2000.

- Michael Greve: Federal German prosecution of Nazi crimes (until 1995); Presentation of various research projects .

- Joachim Perels: The myth of coming to terms with the past . In: Die Zeit No. 5/2006.

- Collection of judgments of all criminal proceedings for Nazi homicides .

- Central Austrian Research Center for Post-War Justice (online since 2002)

Individual evidence

- ↑ See e.g. E.g .: Federal Archives: [1] (PDF; 7.2 MB); Torben Fischer / Matthias N. Lorenz (eds.), Lexicon of coming to terms with the past in Germany. Debate and discourse history of National Socialism after 1945. Bielefeld 2007.

- ^ Günther Wieland: The Nuremberg Principles as reflected in the legislation and rulings of socialist states. In: G. Hankel, G. Stuby (Hrsg.): Criminal courts against crimes against humanity. Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-930908-10-7 .

- ↑ Wolfgang G. Schwanitz : Nazis On The Run (PDF; 1.4 MB), in: Jewish Political Studies Review , 22 (2010) 1-2, P. 116-22.

- ↑ Europe under the swastika. Volume 8. p. 352.

-

↑ Wolfgang Form: Judicial Policy Aspects of Western Allied War Crimes Trials 1942–1950. In: Ludwig Eiber , Robert Sigl (eds.): Dachau Trials - Nazi crimes before American military courts in Dachau 1945–1948. Göttingen 2007, p. 47ff.

Lothar Kettenacker: The treatment of war criminals as an Anglo-American legal problem. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär: The allied trials against war criminals and soldiers 1943–1952. Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 19f. - ↑ ABlAmMilReg. A p. 1

- ↑ cf. the oral report of the then Federal Minister of Justice Fritz Schäffer in the 104th meeting of the Legal Committee of the 3rd German Bundestag on May 11, 1960, short minutes p. 27.

- ↑ ABlKR p. 26.

- ↑ ABlAmMilReg. A p. 7

- ↑ Martin Broszat : Winner Justice or Criminal Self-Purification? Aspects of coping with the past of the German judiciary during the occupation 1945-1949 Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 1981, pp. 477-544.

- ↑ ABlKR p. 50

- ^ Report of the Federal Minister of Justice on the prosecution of National Socialist crimes of February 26, 1965 BT-Drs. IV / 3124 p. 16

- ↑ Art. I No. 1 of Regulation No. 47 of the British Military Government (ABIBritMilReg. P. 306), entered into force on August 30, 1946; Art. 2 No. 5 of Regulation No. 173 of the French Commander-in-Chief in Germany (JournOff. P. 1684), in force since September 23, 1948

- ↑ ABlAHK p. 54

- ↑ cf. BVerfG, decision of February 26, 1969 - 2 BvL 15, 23/68 Rdrn. 43 ff.

- ↑ Federal Law Gazette II pp. 301, 405

- ↑ Katrin Hassel: British War Crimes Trials under the Royal Warrant website of the International Research and Documentation Center on War Crimes Trials , accessed on September 10, 2018

- ↑ Donald Bloxham: British War Crimes Trial Policy in Germany, 1945–1957: Implementation and Collapse . Journal of British Studies 2003, pp. 91–118 (English)

- ^ Bernhard Sprengel: Nazi Trials: Great Britain's Consistent Military Justice Die Zeit , March 1, 2016

- ↑ Cord Arendes: Review of: Moisel, Claudia: France and the German war criminals. Law Enforcement Policy and Practice after World War II. Göttingen 2004 H-Soz-Kult , July 8, 2004

- ↑ War Crimes Trials in the French Occupation Zone in Germany (1945-1953) Website of the International Research and Documentation Center for War Crimes Trials , accessed on September 10, 2018

- ^ The Soviet military tribunal - an inquisition court: "The pronouncement of the verdict was crazy" tagesschau.de , August 25, 2007

- ^ Karl Dietrich Erdmann: The end of the empire and the new formation of German states. In: Bruno Gebhardt (Hrsg.): Handbook of German history. Volume 22. 9th edition. Munich 1999, ISBN 3-423-59040-8 , p. 106

- ↑ Ruth Bettina Birn : The criminal prosecution of National Socialist crimes. In: Hans-Erich Volkmann: End of the Third Reich - End of the Second World War. A perspective review. Munich 1995, ISBN 3-492-12056-3 .

- ↑ Wolfram Wette : The Wehrmacht. Enemy images, war of extermination, legends. Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 3-596-15645-9 , pp. 238f.

- ↑ Auschwitz Trial 4 Ks 2/63 Frankfurt am Main ( Memento from March 2, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ See BGH, judgment of May 20, 1969 - 5 StR 658/68

- ^ Michael Greve: Amnesty of Nazi Aides - A Breakdown? The amendment to Section 50 (2) StGB and its effects on Nazi criminal prosecution Kritische Justiz 2003, pp. 412–424

- ↑ More recently, the Demjanjuk trial and the Lipschis indictment have attempted a further legal appraisal. Hubert Rottleuthner offers a good summary of the process and the debate : Did Dreher turn? About incomprehensibility, incomprehension and incomprehension in legislation and research. In: Legal History Journal. No. 20, 2001, pp. 665-679. See also Norbert Frei: Karrieren im Zwielicht… Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-593-36790-4 , pp. 228f. Stephan A. Glienke: The de facto amnesty of desk criminals. In: Joachim Perels, Wolfram Wette (Ed.): With a clear conscience. Military power judges in the Federal Republic and their victims. Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-351-02740-7 , pp. 262-277.

- ↑ BGH, decision of September 20, 2016 - 3 StR 49/16

- ↑ BGH confirms judgment for aiding and abetting Nazi mass murder ( memento of December 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Die Zeit , November 28, 2016

- ↑ Thilo Kurz: Paradigm shift in criminal prosecution of personnel in German extermination camps? ZIS 2013, 122-129

- ^ Nazi crimes. New charges against former SS guards , Der Tagesspiegel, November 16, 2017

- ^ > Klaus Hillenbrand: Prosecution of Nazi crimes. Responsible even in old age , TAZ, December 18, 2017

- ↑ [7a] Cf. Andreas Eichmüller: The prosecution of Nazi crimes by the West German judicial authorities since 1945. A balance sheet, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 56 (2008), p. 624 ff.

- ↑ Journal I of September 10, 1964, p. 127

- ↑ Article Nazi Trials. In: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. 1998, pp. 1037f

- ↑ a b Rückerl: Nazi crimes in court. Heidelberg 1982, p. 103.

- ^ Karl Christian Lammers : Late trials and mild sentences. The war crimes trials against Germans in Denmark . In: Norbert Frei (ed.): Transnational politics of the past. How to deal with German war criminals in Europe after the Second World War. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2006, pp. 351–369

- ^ Federal Archives (Ed.): Europe under the swastika. Occupation and collaboration (1938–1945). Supplementary volume 1. Berlin, Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 3-8226-2492-6 , p. 111ff.

- ↑ Rückerl: Nazi crimes in court. Heidelberg 1982, p. 102.

- ↑ a b Christian Hofmann: The Eichmann trial in Jerusalem. Arbeitskreis Shoa.de eV, accessed on May 25, 2015 : "The legal basis of the indictment was the" Nazis and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law, 5710-1950 "(NNCL) issued by Israel in 1950, which is based on the" London Statute " of 1945, on the basis of which the International Military Court in Nuremberg was set up and implemented, as well as the Criminal Code Ordinance (CCO) of 1936. […] The appeal lodged by the defense on December 17, 1961 was unsuccessful: confirmed on May 29, 1962 the court of appeal passed the judgment in full. […] On May 31, 1962, the Israeli President finally rejected all requests for clemency. A few hours later the death sentence was carried out. "

- ↑ Emile Krier: Luxembourg at the end of the occupation and the new beginning ( memento of November 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Regionalgeschichte.net, accessed November 9, 2016

- ^ Federal Archives (Ed.): Europe under the swastika. Occupation and collaboration (1938–1945). Supplementary volume 1. Berlin, Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 3-8226-2492-6 , pp. 119ff.

- ↑ War Crimes Act (KVG)

- ^ Norbert Frei (Ed.): Transnational Past Policy , Wallstein-Verlag Göttingen, 2006, p. 218.

- ↑ Article Nazi Trials. In: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust , 1998, p. 1044.

- ↑ See Kim Christian Priemel: Review of: Stoltzfus, Nathan; Friedlander, Henry (Ed.): Nazi Crimes and the Law. Cambridge 2008 . In: H-Soz-u-Kult , February 4, 2010.