Eneasroman

The Eneasroman (also Eneit or Eneide ) is a free adaptation and translation of the French Roman d'Énéas . It was written by Heinrich von Veldeke between 1170 and 1188 . The plot follows the Roman national epic Aeneid , but sets its own accents.

The Eneasroman is one of the oldest profane works in the German language. It is the first German-language court novel of the Middle Ages and the first non-clerical translation of an ancient novel in the German-speaking area. With the poetry Veldeke set standards for a clear and pure style in metrics and rhyme .

action

The novel begins with a brief summary of the destruction of Troy [vv. 1-32]. The gods tell the Trojan Eneas to flee and save his life [vv. 55–57] because he is the son of the goddess Venus [vv. 41-48]. The goddess Juno has let him wander about on the sea for seven years because she is angry with his mother [vv. 156-180]. The conflict between the two goddesses still comes from the Aeneid . Juno and Venus initiate the conflict that resulted from the Paris judgment. Clearly decimated, Eneas and his followers finally reach Carthage, which the beautiful Dido founded [vv. 254-291].

Dido generously grants them help and security [vv. 562–565] and falls violently in love with him when he first meets Eneas [vv. 698-749]. At first she keeps her feelings a secret [vv. 848–861] and cannot sleep the following night because of sheer longing and love for Eneas [1331–1441]. Dido consequently torments himself endlessly [vv. 1387] and only consults with her sister Anna. [Vv. 1460–1470] All of the torments described represent classic "Minne symptoms". Once Dido is in love, this love has all its physical consequences.

One day she decides to go hunting with Eneas and his entourage [vv. 1678-1681]. However, due to a storm, Dido and Eneas are separated from the company and together they seek shelter under a tree [vv. 1824-1829]. Eneas understands how beautiful she is and the two sleep together [vv. 1834–1855]:

“Dô nam der hêre Ênêas / die frouwen under sîn gewant. / well created her si vant. / I understand you with the poor. / do begin ime irwarme / al sîn meat and sîn bloût. / dô heter manlîchen mût, / dâ mite gwan er di upper hant; / the frouwen her underwant. / (...) minnechlîche her si asked, / daz si in becoming / the si same gerde, / (but you spoke against it) / and he put it down, / as Vênûs got: / sine mohte niet. / her tete ir daz her wished, / sô thence here ir kept lovely manlîche. / ir wizzet wol, waz des wied. "

“The noble Eneas / took the lady under his coat. / He saw her beauty. / He wrapped his arms around her. / Then / all his flesh and blood were revived. / Because he was a man, / he gained the upper hand; / he took possession of the lady. / (...) He kindly asked her / to grant him / what she longed for herself / - but she refused - / and he laid her down / as Venus ordered: / She could not defend herself. / He did what he wanted to her / so that he might valiantly keep her affection. / You know well what that was. "

After initially denying it, she finally reveals herself openly as his wife [vv. 1888-1911]. In doing so, Dido also offends the gentlemen of the surrounding countries because after the death of her deceased husband Sychaeus she undertook not to commit herself again [vv. 1919-1949]. This problem is also discussed in Eneas' later underworld voyage. After a while, the gods send a message to Eneas asking him to leave the country [Vv 1958–1969]. He is saddened by this, but wants to do what they ask [vv. 1970-1994]. Dido tries to stop him. She complains and insults him, but fails. [Vv. 2004–2110] After his departure [vv. 2230–2235] she burns Eneas' property left behind, stabs his sword in his heart and then burns himself in the fire [vv. 2423-2433]. Dido portrays this type of death as being particularly masculine, which corresponds to her entire previous appearance [vv. 2423-2440]:

“Dô si daz allez spoke, / with the swerde she stabbed herself / in daz heart dorch den lîb. / al if she were a know wîb, / she was dô vil senseless. / Daz si den tôt alsô kôs, / daz quam of nonsense. / ez was undrehiu minne / diu you dar zû dwanc, / with the stab you spranc / unde much in the glût. / dô dorete daz blooms, / daz ir ûz the wounds flôz, / wande for something big. / deste sheer what verbant / ir give and ir want. / ir meat should melt / unde ir hearts melt. "

“When she had said all this, / she stabbed her heart with the sword / through the chest. / Although she had been a sensible woman, / she was now out of her mind. / That she chose such a death / came from madness. / It wasn't real love / that made her do it. / With the puncture she jumped / and fell into the embers. / Then the blood / that flowed from their wound dried up, / for it was a great fire. / The faster / your container and clothing burned. / Her flesh melted / and her heart burned. "

Shortly before death, she forgives Eneas. [Vv. 2441–2447] Dido is lamented very much and is buried in a princely manner [vv. 2456-2514].

During the trip, the late father Eneas appears [vv. 2540-2547] and tells him to choose his bravest men to go to Italy. But first he should meet him in the underworld. For this purpose Eneas should meet the prophetess Sibyl of Cumae [vv. 2556-2615]. Eneas finds the terrifying Sibyl in front of her temple [vv. 2693-2705]. After the Sibyl learns about Enea's destination, she promises to help him [vv. 2767-2775]. The two set off into the underworld [vv. 2888-2911]. There is great torment and suffering in the underworld [vv. 2941-2951]. Sibylle continues Eneas [vv. 3180–3183] and they meet the hellhound Cerberus [vv. 3198–3199], on the suffering children who died in the womb [vv. 3273–3283], on the fallen warriors [vv. 3310–3311] and to those who have died out of love. Eneas also finds Dido here, but she turns away [vv. 3292-3306].

In the Elysian realms they finally meet the father of Eneas, Anchises [vv. 3576-3585]. He shows him the future in a body of water [vv. 3611-3625]. He also tells his son where he should settle after the journey [vv. 3706-3719]. Sibylle and Eneas are returning to the upper world [vv. 3732-3735].

Together with his entourage, Eneas is now sailing across the sea and arriving at the mouth of the Tiber [vv. 3741-3754]. The King Latinus who resided there welcomed him in a friendly manner in Laurentum [vv. 3924-3927]. He promises Eneas his daughter Lavinia as a woman, plus land and crown after his death. The gods themselves gave it to Latinus [vv. 3954-3960]. Eneas then begins to build Montalbane Castle on a mountain [4050–4069]. The queen angrily reminds her husband that the princess has already been promised to the Rutulian prince, Turnus. [Vv. 4153–4256] He wants to assert his rights against Eneas and gathers a large army around him [vv. 4410-4518]. There are a great many noble and brave men from the most varied of countries and cities in the army of the rotation [vv. 5119-5126]. Also among others the son of Neptune [vv. 5014–5089] and the beautiful virgin Camilla, who behaves like a knight and goes into battle with her female entourage [vv. 5142-5224]. Turnus and his followers decide to lay siege to Montalbane Castle [vv. 5516-5523]. Eneas, however, is well armed with weapons and food so that he can withstand [vv.5538–5551]. Meanwhile, the goddess Venus sees the danger her son is in. She gets along with Volcanus, the blacksmith god, so that he can build splendid armor for Eneas [vv. 5595-5670].

Eneas now moves to Pallanteum on the advice of his mother in order to win the support of King Euander there [vv. 5848-5900]. Because Turnus and Euander are enemies, he sends his son Pallas with Eneas with [vv. 6124-6188]. When Eneas returns with his entourage, the armies attack each other shortly afterwards [vv. 7267-7375]. The fight lasts all day and Eneas kills many enemies [vv. 7397-7447]. Turnus and Pallas also engage in a violent duel in which Pallas is finally stabbed [vv. 7510-7570]. Before Turnus leaves the victim, he steals a ring from his finger. Eneas Pallas gave this ring as a token of the close bond [vv.7599–7615]. Pallas is lamented in pain. [Vv. 7753-7775] [vv. 8125-8234]. His grave is royal [vv. 8240-8373]:

“Nidene was der esterîch / von lûtern cristallen / and jaspide and corals. / the sûle marmelsteine, / the turn of helper legs, / inside of it many a precious stone is stunned. / (...) the stone that was laid / Pallas the kûne, / who what a prasîn green / wants to dig up with his senses. [Vv. 8282-8305] "

“The floor below was / made of clear crystal / jasper and coral. / The columns were made of marble / the walls of ivory, / in which numerous precious stones were set. / (...) The stone in which was placed / the brave Pallas, / was a green gemstone / was carefully engraved. "

The gate is bricked up and only rediscovered more than 2000 years later in the time of Emperor Friedrich I [vv. 8409-8408].

Latinus now consults with his vassals [vv. 8428-8458]. You have just come to the decision that Eneas and Turnus should fight in a duel for wife and crown [vv. 8609–8621], when the two armies begin to fight again [vv. 8742-8768]. The virgin Camilla in particular fights bravely and stabs a mocker [vv. 8964-9027]. But when she tries to take the helmet of a victim, she is pierced from behind by a Trojan horse [vv. 9064-9131]. The dead Amazon queen is weeping, sent home and magnificently buried [vv. 9283-9574].

One evening his mother takes Lavinia aside and advises her to love Turnus [vv. 9735-9788]. Lavinia does not know what love is all about and the mother tries to explain it to her [vv. 9789-9831].

The Queen concludes by threatening to have her daughter killed if she should turn her heart to Eneas [vv. 9966-9990]. Shortly afterwards Lavinia sees Eneas from her window [vv. 10007-10027]. Immediately she begins to love him [vv. 10031-10027]. In a long monologue, Lavinia understood more and more of the love that makes her suffer. She begins to hate Turnus [vv. 10061-10430]. The next day the Queen sees through Lavinias condition and persuades the daughter to write down the name of the lover [vv. 10497-10661]. When she reads Eneas' name, she curses her daughter and curses the Trojan. In doing so, she slandered him and implied, among other things, that he was more oriented towards men than women. [Vv. 10614-10673]. Lavinia defends Eneas [vv. 10674–10687] and finally falls victim to a faint [vv. 10713-10724]. After waking up, Lavinia writes a short letter to Eneas in which she reveals her love for him [vv. 10722-10805]. She hides the letter in an arrow [vv. 80812-10827] and uses a trick to convince an archer to shoot him down in the direction of Eneas. Eneas finds the letter and reads it secretly [vv. 10843-10937]. With Eneas the signs of love now also show [vv. 11024-11035]:

"Do start thinking / sense with all your senses / umb the beautiful lavins, / (...) do start heating and reddening. / heated by minnen in sîn blût / and transformed in sîn mût. / dô wâwand der helt vile mâre, / daz ez another wêwe wâre, / suht or fever or ride: / (...). "

“When he began to think / with all his thoughts / of the beautiful Lavinia, / he got overheated and blushed. / From love his blood became hot / and changed his mind. / Then the great hero thought / that it was a disease / illness, fever or fever: / (...). "

He cannot sleep [vv. 11016–11041] and is now able to understand Dido's torments. Had he done this before, he would never have left her behind. Eneas now sees what guilt he bears for her sake and that love - just like him now - has robbed her of spiritual power [vv. 11180-11193]. So he wants to fight against Turnus for Lavinia all the more resolutely [vv. 11043-11083].

On the day of the duel there was another argument between the comrades in arms of Turnus and Eneas [vv. 11634-11807]. Eneas is hit by an arrow. [Vv. 11851–11886] He is only treated briefly, then reappears on the field [vv. 11888-11920]. Turnus and Eneas finally begin the duel with the sword [vv. 12175-1238]. Turnus does well, but Eneas has such good armor that he is always protected [vv. 12382-12411]. In addition, the sight of Lavinia gives him hope [vv. 12412-12459] so that he gains the upper hand. Turnus now admits everything to Eneas, including the decision about his life [vv. 12460-12558]. Eneas shows pity: he wants to let Turnus live and give him his favor [vv. 12559-12578]. Then he sees Pallas's ring on the hand of Turnus. He avenges his friend and punishes Turnus' greed by beheading him [vv. 12573-12606]. The complaint about the rotation is great [vv. 12607-12609].

The next day, Eneas is warmly welcomed in Laurentum [vv. 12842-12874]. Eneas and Lavinia are filled with happiness [vv. 12878-12891]. There is a solemn atmosphere in the entire splendidly furnished palace [vv. 12971-12964]. Only the queen curses Lavinia and lies in bed for days until death catches up with her [vv. 13086-13092].

The wedding day is celebrated very big [Vv.13088-13119]. There is general generosity [vv. 13165-13200]. Heinrich compares the celebration with the Mainz court festival of 1184 . Eneas becomes a king with power. He lives very happily with Lavinia [vv. 13255-13286]. His descendants include Romulus and Remus, as well as Julius Caesar and Emperor Augustus [vv. 13359-13411]. During this time Jesus Christ was also born [vv. 13412-13428]

Heinrich von Veldeke took over the work from the French. He briefly describes the circumstances of the creation.

If Virgil, the original author of the story, was telling the truth, then the story is true. Because Heinrich translated everything exactly right [vv. 13505-13528].

Characterization of the most important figures

Eneas

The Eneas Trojan is mostly portrayed positively. He is a child of the goddess of love Venus. Cupid himself is his brother [vv. 41-48]. Eneas is therefore extraordinarily beautiful [vv. 10007-10027]. On the worldly side, too, he comes from a noble family [v. 1541]. Some of the greatest hero figures in Roman history grew out of his line [vv. 13359-13411].

Eneas is characterized as determined and efficient, which is evident from the fact that he fortified Montalbane Castle so quickly and safely [vv. 5560-5563]. He also appears to be a very brave warrior [vv. 11888-11920]. The relationship with his followers appears to be extremely good. Eneas was chosen as lord of them [vv. 5945–5946] and when he is injured in battle, the men are afraid because he is not with them [vv. 6354-6357]. Eneas bravely returns to them as soon as possible because he is worried about his comrades in arms [vv. 11888-11920]. He seems to have a personal relationship with each individual, since he tells everyone the good news of Latinus, for example [vv. 4127-4133]. The solidarity among the Trojans even goes so far that Eneas consults with them several times. He does not often make a decision on his own that also affects others. For example, he allows himself to be persuaded to postpone the longingly awaited wedding date with Lavinia at the end a little [vv. 12607–12657] or discusses whether he should really flee Troy [vv. 60-71]. He has few secrets, but among other things keeps silent about his journey into the underworld [V. 2663]. Eneas' ability to be loyal is also evident in his relationship with Pallas: he loves his friend very much and allows open tears after his death [vv. 8078-8088]. The desire for revenge for the young man remains, so that Turnus has to atone in the end [vv. 12573-12606].

The victory over Turnus is a cause for joy for Eneas [vv. 12530–12558], but before he sees the ring, he still shows mercy and mercy towards the enemy [vv. 12559-12578]. He also feels sorry for those who suffer in the underworld [vv. 2988-2990]. Later he shows generosity by distributing many precious gifts [vv. 12965-13015].

Eneas shows fear especially in the underworld [vv. 2653-2655]. The sight of Sibyl also frightens him, but he overcomes his fear [vv. 2689-2695]. In the following years he behaves gratefully and obediently [vv. 2878-2880].

Eneas' loyalty to his father Anchises is also striking. So he has it carried when fleeing Troy because it is so old [vv. 133-135]. On the other hand, he does not seem to miss his wife, who he lost while trying to escape [vv. 140-142].

In addition, one might interpret it as impulsive that Eneas let himself be carried away by Dido's beauty in the forest [vv. 1834-1855]. It is questionable to accuse Enea's cruelty because he then leaves her. Farewell causes him pain [V. 1992], since he never loved a woman as much as she [vv. 2060-2063]. He also strongly advises Dido against suicide [vv. 2102–2105] and later regrets leaving when he meets true love [Vv.11180–11193].

Eneas leaves Carthage because the gods themselves have ordered him to do so [vv. 1958-1969]. He always serves the gods without contradicting [v. 1971], so also with the escape from Troy, the underworld trip and other occasions.

Eneas is also predominantly noble and sincere towards Lavinia. So her letter remains his secret for the time being [vv. 10908–10937] and he thinks largely well of them [vv. 11227-11262]. Love itself is a completely new phenomenon for him, which he gets upset about at first because the feelings seem to cloud his mind. He even feels punished by his divine family members and fears for his life [vv. 11016-11083]. His image of Lavinia fluctuates a few times, for example when he thinks that she wrote such a letter to Turnus [vv. 11227-11262]. He also gives some thought to how he should act now [vv. 11263-11310]. Overall, however, Eneas is not pulled back and forth quite as strongly by his feelings as she is. So, for example, after a waking night, he can at least fall asleep in the morning, while Lavinia gets up again very early [vv. 11342-11403]. At the end he speaks of his infinite gratitude to Lavinia [vv. 2892-12899]. One could draw the conclusion from this that Eneas strives for a relationship with her on an equal footing. This thesis is contradicted by the fact that, newly in love, he decides not to let her know of his feelings because he fears that she might become haughty about them [vv. 11294-11310].

Lavinia

Princess Lavinia is known as junkfrouwe lussam [V. 10455] (lovely noble lady) that is enchanting to look at [vv. 10978-10980]. In the course of the story she shows different sides of herself:

On the one hand, she appears to be pure and impeccable because, among other things, it gives her difficulties in devising a lie for her mother who can tell that she is in love [vv. 10510-10513]. Eneas is also the first man she loves [vv. 10150-10179]. Her virginity was never touched [vv. 12917-12964]. Love is also completely new to her, so that she appears very innocent [vv. 9789-9831]. It is only in the confrontation with the new feeling that much about the nature of love becomes clear [vv. 10216-10239]. She shows a certain fear and despondency towards the queen. After her insistence, she not only admits that she is in love [vv. 10578–10611], but also the name of the beloved price [vv. 10614-10631]. This could also be taken for good faith. Her weakness towards her mother culminates in a faint, triggered by anger and hurtful words [vv. 10713-10724].

On the other hand, Lavinia is sure, if not defiant, in her behavior when she insists never to love a man [vv. 9966-9990]. She stands up to her mother when she begins to slander Eneas and clearly contradicts her in order to defend him [vv. 10614-10687]. At this point, your actions can be described as courageous and strong. Although the girl is frightened [V. 10787], it does not allow itself to be dissuaded from its feelings and even writes a letter to Eneas immediately after the mother's attacks [vv. 10722-10805]. This in turn could be interpreted as either determination or a cry for help. She masters a perfectly formed language in the letter, so she is also educated [vv. 10785-10805]. Eneas is certain, however, that Cupid himself gave her the courage for her actions and the beautiful words [vv. 11263-11291]. The questions that she asks her mother about love seem very naive [v. 9799]. In view of this almost exaggerated uncertainty, many a listener might have suspected that she was only trying to deceive her mother and already knew more about love than she was willing to admit.

Lavinia shows prudence when she does not hide the letter to Eneas but keeps it with her [v. 10810]. She even devises a ruse to get the letter to him. She also tells a lie and puts the archers in a certain danger of breaking the armistice [vv. 80812-10912]. One could assume that Lavinia was cunning, but also skill and eloquence or diplomacy.

Lavinia shows a moral sense when at the end she makes it clear to her mother that suicide would be foolish [vv. 13063-13085]. Although she insulted her, she also spoke to the queen with liebiu mûder mîn [v. 13085] (dear mother). It therefore seems meek, or in this case, soothing.

In her violent love [vv. 10468-10496] Lavinia is determined to Eneas. Even after a severe disappointment, she cannot let go of him [vv. 11368-11422]. At the end it is said that she shows her husband constant loyalty and affection [vv. 13329-13330]. However, her image of him fluctuates several times in the course of the story. For example, she briefly considers that he could really be homosexual [vv. 10760-10771]. Still, her emotions seem to be more of a momentary turmoil than what could be described as fickle. At the end of her inner monologues, she finally always convinces herself of the good in Eneas [vv. 10774–10784] and cannot be dissuaded from their hatred of Turnus [vv. 10302-10313].

Dido

Dido is a woman with extraordinary power [vv. 290-291]. She rules over the rich and powerful Carthage, which she herself founded [vv. 287-291]. Dido is also shown respect for her cleverness [vv. 407-409]. When she arrived in Libya, she used a ruse to acquire a great deal of land and ultimately all of Libya [vv. 294-348]. Dido is extraordinarily beautiful [vv. 1700f] and also has splendid jewelry [vv. 1687-1741]. Veldeke writes that she looks like Diana, but that she has a softer heart [vv. 1794-1797]. She also proves this when she welcomes Eneas and his messengers in a friendly and generous manner [vv. 455-456]. At the same time she shows her strength because she has always rejected the marriage proposals of the rulers of the surrounding countries [vv. 1919-1949]. She herself claims that she wanted to remain loyal to her deceased husband in this way. With regard to Eneas, she lets her sister Anna talk her out of this argument [vv. 1485-1495].

Dido's security, which she shows as the sovereign ruler, seems to be losing towards Eneas. On his arrival she falls violently in love with him, which was brought about by Venus and Cupid [vv. 739-749]. An arm jewelry that he gives her suddenly means as much to her as her life [vv. 1314-1316]. For the time being she keeps her feelings a secret because she doesn't dare to confess her love to him [vv. 848-861]. She generally seems to have less self-confidence towards Eneas than was otherwise the case. So at first she thinks Eneas is too good for herself [V. 1556] and Anna has to encourage her [vv. 1473-1480]. Dido knows that she could endanger her position through rash actions [v. 1303]. Nevertheless, she likes to give herself up to the Trojan in the forest. At first she defends herself, but then lets herself be overwhelmed by her love for him [vv. 1849-1855]. Only later does she regret that she complied with his request so quickly [vv. 1881-1884]. Because of her passion for Eneas, she seems to have lost some of her prudence. This is also expressed in the fact that she is not interested in the gentlemen of the surrounding countries now angrily trying to damage her reputation [vv. 1919-1949]. This could also be assessed as good faith, because it should probably have been clear to her that a public commitment to Eneas would have such consequences. Heinrich writes, however, that by going public she wanted above all to play down the shame that her illegitimate misstep has brought on her [vv. 1912-1915].

When Dido found out about Eneas' departure, she finally seemed to have lost all independence: for example, she fears that she will no longer be able to defend herself against the surrounding rulers [vv. 2190-2191]. This outside threat is very real. So her pleading is probably not just a pretext to prevent him from going away. Dido also loses her composure when the Eneas insults [vv. 2210–2229] and repented of all the gifts she gave him [vv. 2121-2123]. After his departure, Dido burns everything he has left behind [vv. 2230-2235]. She seems to be able to endure her abandonment even worse than her previous infatuation, which is why she sends Anna away on an excuse [vv. 2264–2269], only to take his own life with the sword of Eneas [vv. 2423-2425]. Neither Eneas nor her followers would have trusted her to do such a thing. Dido was considered too clever and controlled for that [vv. 2516-2528], which illustrates the change she makes during the narrative.

Analysis of form and content

At the beginning of the Eneasromans, the story in verses 1-2528 revolves mainly around Dido and the events in Carthage. After her death, Eneas begins the journey through the underworld in verses 2529–3740 and lands a little later in Italy. Verses 3741–6302 tell of the preparations for the battle for Italy, which is spoken of in verses 6303–9734. In verse 9735 the big part about Lavinia begins when her mother takes her aside to talk. The duel for the king's daughter and Italy is decided. Finally, in verses 13429-13528, there is the epilogue. The action is repeatedly interrupted by detailed descriptions. They concern, for example, magnificent clothes, graves, combat equipment or processes in the soul.

The course of the action is chronological. There is a commentary narrator, as well as numerous monologues and dialogues.

The Lavinia story is much more extensive than that of Dido. In many ways Heinrich von Veldeke draws parallels between Didos' love and Lavinias. The big difference, however, is that Eneas seriously reciprocates feelings for Lavinia, but Dido's love remains unrequited. The happiness and sorrow of love are thus juxtaposed. At the same time, a bow is drawn from the love of sovereignty: because Eneas follows his destiny and leaves Dido behind, she throws herself into his sword. Neither of them will now continue to rule Carthage.

The great love for Lavinia, which Eneas also supports in the duel, opens up a dynastic future perspective for all of Italy. The arc of suspense reaches its highest point in the duel between Turnus and Eneas. The tension is built up more and more beforehand, as the preparations for the fight take up a lot of time. Likewise, the battles and the circumstances that postpone the duel again and again. The audience with Eneas is not only excited about the royal crown, but also about his luck with Lavinia. The love between the two is threatened in several places, for example when Lavinia's mother slandered the Trojan [vv. 10614-10673].

While the Aeneid is clearly divided into sections, there is no apparent structure in the Eneasroman. Only the Eibach manuscript from the 14th century divides the poem into six parts, which differ considerably in their verse. It is controversial whether Veldeke is behind this arrangement.

The Eneasroman is written in short verse rhyming in pairs. What is striking is Veldeke's striving for pure rhymes in order to avoid assonances. The metric (verse doctrine) of the verses is very regular. Veldeke was one of the first poets to use such an even and clear style. In the dialogues one can often find stinging myths.

Heinrich von Veldeke probably originally wrote the poetry in West Central German. Some Lower Franconian forms from the local dialect can still be found.

Position in the work of the author and the genre

The Eneasroman can be assigned to the early court epic. The courtly novel is Heinrich von Veldeke's most important work. In addition, more than 30 single-verse lyric works based on Romansh models have survived, which testify to his high level of education. He used an expressive imagery in his minne songs and played with shapes and motifs. Before the Eneasroman, Heinrich von Veldeke also wrote a legend with more than 6000 verses. The theme was the life and work of Saint Bishop Servatius, who was the patron saint of Maastricht. This work was intended to increase the veneration of pilgrims who did not speak Latin.

Heinrich chose a West Central German language for his main work, the Eneasroman, but made it possible for the novel to be read in the dialect of his homeland, Lower Franconian. At the same time he opened access to the High German literary center.

Heinrich's role model in language and understanding of love affection was Ovid: “The great teacher is Ovid, a school author since the 12th century, not only for the symptoms of love affection, but also for the light, unpathetic. u. thus ungilious expression in a highly flexible, partly ironic, partly psychologically nuanced dialogue. "

Heinrich von Veldeke was the first poet to give the German-speaking audience an accurate picture of a courtly novel. This genre was later completed in the Arthurian novel.

Shortly after the middle of the 12th century, three court novels were written at the Anglo-Norman court, which dealt with ancient history, but showed them in the contemporary garb of the court. This also includes the Roman d'Eneas, which was the template for the German Eneasroman. [More on this in the section "Comparison with the French novel d'Eneas"] The narrative patterns of these novels were more modern in content and form than the usual hero and story poems. The heroes of Troy were considered the ancestors of medieval chivalry. Eneas was awarded to have carried the knighthood from Troy to Rome. The so-called "ancient novel" also served to legitimize rule. In the Eneasroman Heinrich also made a point of describing the story. The ancient world was left in its own world, even though it was shaped by the knighthood of the Middle Ages. In the German-speaking world, the genre of the antique novel never achieved the same meaning as in French. Accordingly, there is no other known medieval attempt to depict Virgil's Aeneid in German.

Comparison with the Aeneid

The Aeneid, written by the Roman poet Publius Vergilius Maro , is considered the national epic of Rome and was written between 31 and 19 BC. Heinrich's main source was not the Aeneid, but the French novel d'Eneas, which Virgil had edited. Horst Brunner writes about the changes:

“The French author has not only reduced the role of the ancient gods, he has also simplified Virgil's structure considerably. Instead of a complicated representation, in which the past (the fall of Troy), narrative present and future (future greatness of Rome) are always kept present in the consciousness of the listener and reader at the same time, there is a simple, sequential structure. At the same time, the Virgilian pathos has been replaced by an elegant, sometimes downright chatty narrative tone. "(Sic!)

In many ways, the differences between the Aeneid and the Eneasroman therefore also apply to the Roman d'Eneas. Heinrich von Veldeke also used Virgil for his adaptation, as is clear, for example, from the detailed description of Sibylle: In the novel d'Eneas there are only 4 verses, in the Eneasroman 33.

In the medieval Eneasroman the power of the empire is no longer the goal of the story. Instead, Aeneas is transformed into Eneas and the model of chivalrous behavior. It is described as reprehensible that he fled from embattled Troy. The comrades in arms appear as knights and all of the ancient material appears in the garb of the courtly world. The power of love is the central theme, illustrated by the episodes about Dido and Lavinia. The main change in relation to Virgil is therefore Lavinia's important role at Veldeke. It hardly plays a role in the ancient epic. With Heinrich, however, it almost becomes the cause of the war.

Virgil begins his story in the middle of the action. The beginning is therefore very complex. The prehistory - the fall of Troy - is only reported later. The Aeneid is formally quite closed and consistently structured. Nevertheless, reference is made several times to the past or future. Because Virgil does not tell the events in chronological order, he can make the goal and the task of Eneas clearer.

Heinrich starts at the beginning of the events and follows the sequence of events. He reports in the ordo naturalis and emphasizes right at the beginning that it is necessary for Eneas to flee Troy.

Virgil divides his epic into twelve separate books. [More on this in the article “ Aeneid ”] The novel d'Eneas does not adhere to this classification, Heinrich deviates from it even more. Such is the content of Virgil's XII. Book in the Eneasroman designed in over 3953 verses, while the content of III. Buchs - a report on the wanderings on the way to Carthage - has been completely deleted. Dieter Kartschoke suggests that the following sections roughly correspond:

| Aeneid | Roman d'Eneas | Eneasroman |

|---|---|---|

| I. book | 1-844 | 1-909 |

| II. Book | 845-1192 | 910-1230 |

| III. book | 1193-1196 | ------ |

| IV. Book | 1197-2144 | 1231-2528 |

| V. book | 2145-2260 | 2529-2686 |

| VI. book | 2261-3020 | 2687-3740 |

| VII. Book | 3021-4106 | 3741-5312 |

| VIII. Book | 4107-4824 | 5313-6302 |

| IX. book | 4825-5594 | 6303-7266 |

| X. book | 5595-5998 | 7267-7964 |

| XI. book | 5999-7724 | 7965-9574 |

| XII. book | 7725-10156 | 9575-13527 |

Virgil's books each contain between 705 and 952 hexameters. The corresponding parts from the Roman d'Eneas vary between 4 and 2432 verses, the sections from the Eneasroman even between 0 and 3953 verses:

| Aeneid | Roman d'Eneas | Eneasroman |

|---|---|---|

| I. 756 | 844 | 909 |

| II. 804 | 348 | 321 |

| III. 718 | 4th | ------ |

| IV. 705 | 948 | 1298 |

| V. 871 | 116 | 158 |

| VI. 901 | 760 | 1054 |

| VII. 817 | 1086 | 1572 |

| VIII. 731 | 718 | 990 |

| IX. 818 | 770 | 964 |

| X. 908 | 404 | 698 |

| XI. 915 | 1726 | 1610 |

| XII. 952 | 2432 | 3953 |

Heinrich von Veldeke, like most German-speaking medieval poets, did not divide the plot of his poetry into any books. The Eibach manuscript alone, from the 14th century and lost today, divides the events into six sections. These vary considerably in the number of verses. Whether Heinrich made this classification himself is disputed.

Heinrich presents the story as a fictitious dialogue between the narrator and the listener. He mediates between the story and the listener by turning to the audience. At the same time, there is a certain distance between the narrator and the story, which is characterized by referring to sources. The verses about Christ also show that the poet feels more connected to his audience than to the characters in his poetry. Virgil, on the other hand, “takes an autonomous position in relation to his audience.” (Brandt) Even personal comments are not directed at the audience, but rather at the muse.

Virgil starts his work with a Proömium. It is divided into three sections, in which the most important points of the following events are announced. Thus, in the introduction, Juno's anger against Aeneas is reported. Juno knows that descendants of the Trojans will destroy the city of Carthage. But she loves this city. Juno and Aeneas appear as opponents from the start. Brandt describes the necessity of these opponents as follows:

“The ideal goal of the epic is the size of Rome. The way to this greatness must be fought for by overcoming 'casus' and 'labores'. The confrontation with the arch opponent Carthage is the historical symbol for this path full of sacrifices, Aeneas the mythical incarnation of the powers and virtues that made Rome's world domination possible. "

Carthage must therefore fall on the way to rule Rome, as already indicated in the Proömium. Brand also points out that in addition to Juno and Eneas, Proömium is also dominated by a higher power, namely fate. The meaning and aim of the story are hidden in his plan and saying. The ultimate goal of Eneas' task was Rome. For this reason, Juno can only put obstacles in the way of the hated Trojans, since they too are bound to fate.

In contrast to Virgil, Heinrich von Veldeke does not precede the story with a prologue. This seems unusual precisely because medieval poets usually preceded their story with a prologue. It remains unclear why Veldeke did without it, especially since he also wrote an epilogue and otherwise did not strictly adhere to the template - which also does not require a prologue. Instead, Veldeke briefly describes the events around Troy at the beginning, partly from the Greek and partly from the Trojan side. There are therefore no indications of how the novel will end. Content-related and syntactic transitions are made clear at the beginning by breaking rhyme . A break in the pair of rhymes can be found with every change in the content or with a change of direction. The goddess Juno is also not mentioned at the beginning, because her role is clearly limited in the Eneasroman. Her action is essentially limited to the journey across the sea, which is made more difficult by storms. While Juno represents the opponent of Aeneas for Virgil, Turnus is more important for Veldeke. He acts as an antagonist at eye level. Heinrich almost completely erases the narrative level of Olympus and the gods, which is also clear at the end of the two works. For the Roman poet, however, the world of gods plays a major role: For Virgil, events take place both at the beginning and at the end in the divine and earthly realm. The description of the duel between Aeneas and Turnus is also interrupted by a scene in the realm of the gods. This should not only make the event more exciting, but according to Brandt also make it clear how closely the two levels of action are related to one another. Figures from the world of gods also intervene in the fight several times. Turnus loses the duel because the gods are no longer at his side, so he is insecure and confused. Jupiter sends one of the diren for this purpose. Aeneas kills the enemy because he has taken Pallas' ring. Virgil's epic ends there. The last verse refers to the fallen rotation: Vitaque cum gemitu fugit indignata sub umbras. (And with a sigh his angry spirit escapes to the shadows.) Thus, both in the Proemic and at the end, the sufferings are told to the people, and the end of Virgil's work is disturbing and dramatic. Brandt justifies the need for such an ending as follows:

“From the point of view of Virgil's conception of art, it is unnecessary, in fact it would mean a violation of the drama and coherence of the work if he were to tell the story of Aeneas to the end. Everything that is necessary has already been said or indicated: Lavinia will consent to the marriage, Aeneas will found Lavinium, unite the peoples, die after three years of reign and be raised to the gods. The occurrence of these events cannot be doubted; it does not need to be confirmed by a further narrative by the poet. (...) The entire event of the epic is summarized at the beginning and the end. "

Since everything important in terms of content has already been conveyed to the reader, additional words would destroy the effect of the epic.

Heinrich's Eneasroman does not end with the death of Rotus. He also tells of the love between Eneas and Lavinia, the death of the queen and the great wedding. So there are around 800 verses that also tell of the future of Eneas and his descendants. The birth of Jesus Christ is linked to the time of Augustus. That is why Heinrich closes the narrative part with a brief closing prayer and the words âmen in nomine domini. (Amen, in the name of the Lord) The plot does not end with a concrete event in the life of the protagonist. Eneas' curriculum vitae appears open to the front and back. In contrast to Virgil, Heinrich does not name any dates either, but instead inserts the entire event in time, tied to events that are familiar to the audience. The fall of Troy and the birth of the Son of God form the "cornerstones" (Brandt) between which the story of Eneas and his descendants runs.

While Virgil makes a clear distinction, Heinrich creates flowing transitions and also ties in with the present - for example when the Mainz Court Festival is mentioned. In the end, Eneas and Lavinia promise each other the loyalty they need to continue their happy life. Happiness culminates in the birth of their child, that is, in the offspring in which the characters still live. This is particularly evident in the last appearance of Lavinia’s mother, which serves as a contrast: the queen casts her daughter out. She wishes she had killed the child after it was born. Without accepted offspring and with the loss of her daughter who opposed her, her life seems pointless. Death will soon take them away. In this way, the beginning of the epilogue also indicates the victory of life over death, since Eneas and Lavinia eventually produce offspring.

The two authors' image of man differs significantly from one another: in the Aeneid the name of the protagonist is mentioned relatively late. In this way, Virgil succeeds in making it clear that it is not the figure that should be in the foreground, but the determination that it has to master.

Heinrich von Veldeke, in contrast, tends to focus on the Trojan's individual résumé. The life of Eneas makes it clear that it is possible to become happy and at the same time to fulfill the task set by fate. Veldeke's work is accordingly based on a more optimistic view than Virgil's.

Comparison with the Roman d'Enéas

The novel d'Eneas was written anonymously in the 1250s. He is considered Heinrich's immediate source. The Eneasroman is not a strict translation of the old French work, but rather a free adaptation. This can be seen, for example, from the fact that the Roman d'Eneas is only about 10,000 verses long. The Eneasroman, on the other hand, contains more than 13,000 verses. This is also because it is more difficult to rhyme in Middle High German than in Romance languages. Heinrich often had to lengthen an old French pair rhyme to double the number of verses.

The Eneasroman differs in many places from the Roman d'Eneas. Heinrich von Veldeke did not exactly follow the template, but set his own accents and changed many details. This is particularly evident in the most important scenes and the representation of the characters. Rodney W. Fisher writes:

"Veldeke thus focuses our attention on the human qualities of the hero, whereas the Roman d'Eneas reminds us of the transience of both good and bad, success and failure, almost as an implicit condemnation of over-hasty rejoicing." (Veldeke directs so our attention to the human qualities of the hero, while the novel d'Eneas reminds us of the transience of good and bad, success and failure, almost like an implicit condemnation of hasty joy.) Accordingly, one can also make a different one from the two novels Pull morale.

After Eneas' arrival in Carthage, the novel d'Eneas generally speaks of the ups and downs of Fortuna's wheel. Heinrich leaves out this part, instead he reports on the splendor of the hero's clothes. Fisher suspects that Heinrich preferred to describe the pomp at court - also later, for example, with Dido, Camilla - instead of taking up the moralizing tone from the novel d'Eneas. The poet probably wanted to forego portraying the protagonist as irresponsible or presumptuous towards Fortuna.

Dido is portrayed in the novel d'Eneas as a woman with strong emotions. Venus makes her love Eneas by putting the fire of love on the mouth of the Trojan's son. When Dido kisses him in greeting, the fire spreads to her. The fateful kiss is dragged out much longer in the novel d'Eneas and after that she always seems to be on the verge of losing her self-control. In the novel d'Eneas, Dido also appears very passionately the following night. Her "erotic delirium" (Fisher) is shown here relatively explicitly. The French novel closes the Dido episode by upholding morale: her epitaph proclaims that she has loved too mad. Heinrich's Dido appears much more reserved. So she worries about whether it would be decent to take the first step on the beloved and hides her feelings. At night she reflects on her situation in detail in direct speech. Heinrich even seems to justify her after the cohabitation scene when he expresses her feelings as rehtiu minne [V. 1890] (right Minne). In contrast to the point in time after her suicide: There is von undrehiu minne [V. 2430] (improper love) the speech. Several times in the entire Dido episode he draws parallels to Lavinia's later love. Heinrich therefore seems to be more benevolent towards her than the author of the Roman d'Eneas.

Dido's love is also expressly triggered by Venus and Cupid, which is not the case in the novel d'Eneas. The circumstances of the scene are described in Heinrich in such a way that Eneas can neither notice Venus nor the vehemence of Dido's feelings. Probably this should make it easier for the audience to forgive Eneas if he later leaves Dido.

The portrayal of Lavinia also differs in the two works. In the novel d'Eneas, the princess seems to be very inquisitive, to learn what love is. She asks her mother clear questions as the two talk about it. Heinrichs Lavinia seems to be confused by the phenomenon of love. She picks out unknown idioms and asks what they mean, and even seems to deliberately misunderstand some things. In this way the audience is tempted to suspect that Lavinia knows more about love than she likes to admit. In spite of everything, Heinrich portrays Lavinia as a figure who can think very analytically. For example, she thinks carefully about how to send her love letter to Eneas. [Vv. 80812-10937]

Heinrich also sets his own accents in Eneas's monologue on love. While the French Eneas mainly draws strength and confidence from love, the German Eneas is also gripped by fear because pain and insomnia could weaken him in battle. Veldeke lets fear appear as a kind of barometer to illustrate the development of Eneas: While Eneas is frightened again and again in the first scenes - for example in the underworld - the fear now reappears after a long absence and then finally closes disappear. In Lavinia too, the feeling of fear is more pronounced than in the French novel. The German poet in particular seems to have made a point of drawing a parallel between the state of Lavinia and the state of Eneas, as the recurring motif of fear makes clear. After Eneas does not show up the morning after receiving the letter, Lavinia fears the loss of her honor much more than in the novel d'Eneas. Instead, as always, the novel d'Eneas is much more explicit at this point in the representation of sexual themes. Lavinia seems to be surprisingly well informed about homosexuality when she ponders whether her mother might have been right about the slander after all. [More on this under the section "Masculinity"]

The novel d'Eneas only tells the essentials of the duel. The Eneasroman is much more detailed and describes, among other things, the preparations and the horses as well as the environment during the fight. That is why only the German Eneas can be spurred on by the sight of Lavinia. Heinrich also deliberately lets more tension arise in the fight scene because Turnus is a tough opponent here. He defends himself for a long time and also uses Eneas vigorously. In the novel d'Eneas, on the other hand, Turnus appears less heroic, paces back and forth and tries to call his friends for help.

Fisher suspects that the representation of the strong rotation should give Eneas' victory more shine:

“ Suffice it to say that Veldeke is concerned here to stress Turnus stature as an opponent (...), not only because this adds to Eneas 'honor as victor, but more importantly, because in defeating an opponent of Turnus' qualities Eneas can emerge from the shadow of his earlier shameful escape from Troy and prove himself worthy of what the gods or fate have in store for him. ”(Suffice it to say that Veldeke tries to emphasize the position of the rotation as an opponent, (...) not only because this increases Eneas' honor as a winner, but, more importantly, because the victory over an opponent of Turnus' quality lifts him above the shadow of the shameful escape from Troy and proves him worthy for what the gods or fate have in store for him.)

In the novel d'Eneas, the audience is clearly drawn to Eneas' side when he finally kills Turnus: Pallas must be avenged so that Eneas is better off. This passage is a rigid narrative in French with no commentary. Heinrich differs significantly here. Eneas accuses Turnus of his greed, which suggests that this is one of the main reasons why Turnus must die. The eulogy for Turnus that follows can only be found in German. It is said that Turnus should have died because it was so destined for him. Heinrich makes it clear at this point that the hero's task and fate are of great importance.

Heinrich also emphasized the historical and political aspects of the work. It briefly describes the history of Rome and ends with Emperor Augustus. From here a parallel is drawn to the birth of Jesus Christ, which occurs at the same time. Heinrich even ties in with the present by briefly reporting on the Mainz court festival of 1184, which he compares with the great wedding feast of Eneas and Lavinia.

History of origin

The genesis of the Eneasromans is told to us at the end of the work in verses 13436-13470. In research it is controversial whether Heinrich wrote the part himself or whether it was added later: The novel ends with two sections in which the author is named twice. So it is possible that two different versions of the epilogue were placed side by side.

It is said that Heinrich was promoted by the Countess von Cleve. He lent her the seal when he had only got to the point where Eneas received the love letter. At the wedding feast of the Countess and Ludwig of Thuringia, however, a lady-in-waiting was careless, so that she lost the manuscript. Count Heinrich had stolen them and sent them to his home in Thuringia. Nine years later Heinrich stayed there as well and got the manuscript back through the mediation of Count Palatine Hermann von Neuenburg - brother of Landgrave Ludwig III. The work is therefore also dedicated to the Thuringian Count. Thanks to this information, it is possible to estimate the time of writing the novel unusually well. Heinrich probably began to write it soon after 1170. Most likely the manuscript was stolen in 1174. Heinrich regained it in 1183 and probably finished it between 1184 and 1188.

The meaning of verses 13461 f. from the epilogue are controversial:

daz mâre dô were written / otherwise dan obz remained in the war. (There the story was written in a different way than if it had stayed with him.)

The verses indicate that the poetry was changed in Thuringia against the will of the author. To this day it remains unclear which verses could not have been written by Heinrich. Dieter Kartschoke suggests that the poet probably ended the work differently than he originally planned. His new client could have prompted him to do so.

Lore

There are relatively many traditions of the Eneasroman. Kartschoke refers to a total of twelve manuscripts: six are more or less complete. In chronological order these are the manuscripts B, H, M, E, h and G. A testimony from the 15th century, w, is greatly abbreviated. There are also excerpts from five other manuscripts: R, Me, P, Wo, Marb. The text witnesses B, h and w have illustrations to show. The manuscripts Me and E were lost after their discovery and are now lost. The dating of the tradition ranges from the end of the 12th century with R and Wo through the 13th century with Me, B, P, Marb and the 14th century with H, M and E to the 15th century with h, H and w . [More on the manuscripts in the article Heinrich von Veldeke ]

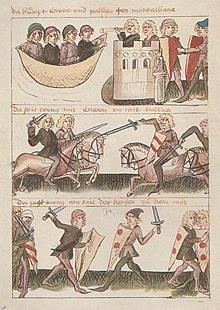

Of the greatest importance is the Berlin parchment manuscript B. It dates from the beginning of the 13th century and was probably written only 20 or 30 years after the poetry was made. The copy contains 136 full- and half-page miniatures, pen drawings with banners. They are kept in the style of Romanesque Bavarian book illumination. Kartschoke describes this tradition as "(...) probably the most beautiful handwriting of a German poem from this early period."

The traditions have their roots in a Thuringian master handwriting. This was obviously rewritten from Limburg into Thuringian, most likely with the help of Veldeke. The majority of the traditions are written in Upper German, some also in Middle German.

The Eneasroman is the first Middle High German work, the text of which has not undergone any drastic changes over the centuries.

Possible interpretations of selected aspects

Love

Love is the main element of the Eneasromans: it connects Eneas with Dido and causes them to commit suicide. At the same time, love connects Eneas with Lavinia and is thus also the cause of the argument with Turnus. The love is always caused by the goddess Venus. This theme of love distinguishes the epic from the courtly novel. Worldly love receives more attention here than ever before in German literature. The first cohabitation scene in the courtly novel can also be found in the Eneasroman [vv. 1832-1863].

In addition to the love affair, the eneasroman deals with thoughts about the nature of love, minnemonologists and dialogues, a teaching about love, the love letter and the death of love.

After Lavinia's mother tries to advise her to love Turnus, she asks the well-known question: dorch got, who is diu Minne? (My God, who is this Minne?), In other manuscripts: waz ist diu Minne? [V. 9799] (What is love?) The answer is an instruction from the mother about the nature of love: love is eternal and is neither audible nor visible. The essence of love can only be understood by those who are accessible to it. You could then bring insights:

'So done is diu minne, / daz ez rehte no one / can say to the other, / to sîn heart sô stêt, / daz si dar in niene gêt, / who lives sô stone: / swer ir but rehte desebet / unde zûr ir kêret , / vile si in des lêret, / daz im ê was unkunt. ' [Vv. 9822-9831] ('Love is of such a kind / that no one can explain it straight away / to another whose heart is so such / that it cannot get into it / because it is so hardened: / Whoever it is but feels in the right way / and turns to her, / she teaches him a lot / that was not known to him before. ')

However, love also brings torment. The mother now lists the symptoms that the love affection brings with it: One moment is hot, in the other it is cold. One suffered from anorexia. The color of the face changes constantly and one is restless and sleepless because the thoughts are only for the loved one. This affectionate sickness expresses itself with all its signs both with Dido and later with Eneas and Lavinia. Until the 19th century, such symptoms were actually assigned to a disease under the name "Morbus amatorius". Lavinia no longer wants to have anything to do with love because she is put off by the idea of such suffering. But her mother thinks that no one can protect himself from love. On the one hand it is bad, on the other hand it also brings great luck. A fulfilled love would also bring joy and calm. Lavinia holds on to the painful sides of love in dialogue, while her mother now emphasizes the joyful ones. Happiness grows out of the necessary misfortune. Love has an ointment that would make you healthy again. The duration of the suffering is left to fate. Nevertheless, Lavinia sticks to her decision at the end of not wanting to know anything about love. This upsets her mother.

In fact, love sickness is also an ailment in the novel with an uncertain outcome. One can be healed through the fulfillment of love, but death threatens without healing. This makes the end of Dido clear. This makes Lavinia's non-normative action all the more understandable to take the first step towards Eneas. Bernhard Öhlinger is of the opinion that it is fear of death that enables Lavinia to write the letter. She could have the image of Dido in mind, after Bernhart Öhlinger the most important example of a love-dead person in literary history. Finally Dido loses everything, but forgives Eneas in death. In contrast to other characters in literature - for example Sigune or Kriemhild - she takes her end into her own hands and does not die slow death of a broken heart. Likewise, she does not hold a third party accountable, as does Vergil's Dido when she casts a curse. Heinrich von Veldeke also demonstrates that Dido is not an isolated case, as the visit to the underworld proves.

After Dido's death, her love for Eneas is seen as “unjust love” [v. 2430]. The reason could be that her feelings drove her to suicide, which was considered a sin in the Middle Ages. That is why it is also said that the devil advised her to do so. In addition, in contrast to Lavinias, Dido's Minne did not help to advance the heavenly plan of salvation. Because only the connection to Lavinia allows Eneas to become an ancestor of Rome. Both Dido's sister Anna and the narrator raise doubts about her sanity in the face of her suicide. She would have loved too much and therefore lost her mind. This immensity is of great importance. Still, Lavinia seems to have the same feelings. She suffers from the same mine disease and also has thoughts of suicide. The difference between her behavior and Dido is that she does not act. She loves Eneas no less than the ruler of Carthage did. The big difference between the two women’s love is that Dido's love remains unfulfilled in the long run, while Lavinias is fulfilled. H. Sacker describes the situation very aptly:

"Whereas Eneas falls head over heals in love with Lavinia, he only flirted with Dido". (While Eneas falls head over heels in love with Lavinia, he just flirted with Dido.)

So the difference is not in the feelings of the two, but in Eneas' response to it.

Renate Kistler writes: "If there is a difference between the Dido episode and the Lavinia episode, it is not in the women, but in the behavior of Aeneas."

In addition to the happy ending of the Lavinia episode, the eneasroman also repeatedly shows the fatal consequences that can result from love. The first verses of the work already deal with the Trojan War, which was triggered by the robbery of a woman. This misfortune is highlighted three times in the novel. The battle for Lavinia, however, is not a mine war in the strict sense. Lavinia's love is closely linked to the argument, but Turnus and Eneas are also about the land and the royal crown.

masculinity

After learning that her daughter loves Eneas, the queen tries to dissuade her. [Vv. 10630-10673] [See the “Action” section for more on this] Your anger appears violent and inappropriate. Finally, she slandered the Trojan and denounced his manhood:

"Ezn is to sayenne niht gût, / waz on with the men tû, / therefore wîbe niene gert. / dû wârest ubele zime valued, / wander never wîb loved. / phlâgen all those who / the evil side of her phliget, / den her vil unhôhe wiget / the unsâlege Troiân, / diu werlt should almost zergân / within a hundred years, / (...) nû hâstû wol vernomen daz, / like unrotated lôn / frouwen gave Dîdôn, / diu ime gût and êre bôt: / she beleib through in tôt. / from ime quam never wîbe gût, / tohter, nor ouch dir ne tût. ” [vv. 10647-10670] (“It is improper to report / what he does with men / that he does not desire women. / You would be badly served with him, / because he has never loved a woman. / Would all men / the follow bad habit / to which he does not attach great importance, / the corrupting Trojan, / the human race would have to perish / within 100 years, / (...) Now you have heard well / what bad reward / he gave Lady Dido, / who has given him gifts and honor: / She sought death because of him. / Through him nothing good came for a woman, / daughter, not even for you. ")

The Queen refers to Dido, who was left unhappy and faithless by Eneas. Dido symbolizes all women to whom Eneas is said to have only brought bad things. She was left without a child, which was partly responsible for her sad end. The Queen accuses Eneas of not wanting to reproduce, because he rather turns to men. He has never loved a woman. She rates this as reprehensible and immoral - a moral judgment that was made by the Benedictine monk and Bishop Petrus Damianus in the “Liber Gommorrhianus” as early as 1049. The mother adds: If all men behaved like him, people would have to become extinct within 100 years. Lavinia's mother reminds her child that the royal family's dynasty cannot be maintained if she marries Eneas. The gender should die out. The downfall of Carthage, caused by the suicide of the childless ruler Dido, is proof of this. Eneas' fornication itself is not the main charge. The mother later argues that Eneas is a coward. In fact, he fled his embattled hometown of Troy. [Vv. 55–57] Marriage to such a coward dishonors Lavinia's entire family. Heinrich sets an accent here that distinguishes him from Virgil and the Roman d'Eneas. He leaves out parts of his template and rearranges arguments. In this way the poet emphasizes the dynastic future perspective that must be preserved. A wrong marriage or affection can jeopardize the rule of a family. The big reproach against Eneas is that he will not father any offspring even though Lavinia loves him. In this way the queen tries to question his manhood.

In the novel d'Eneas, masculinity is questioned by other means: the accusation of fornication is more in the foreground in the French version. Here, too, Eneas is portrayed as an enemy of women. The mother says that Lavinia would suffer mainly because she was constantly in competition with men whom Eneas would desire more. The queen claims, among other things, of Eneas that he did not know how to penetrate through “the small gate” ( “ne passereit pas al guichet” ). This denies him the ability to have vaginal intercourse. But anal intercourse was also rejected by Bishop Petrus Damianus and thus regarded as a sin. Furthermore, Lavinia should only attract other men after the wedding, who would sleep first with her, then with Eneas. The sexual metaphors used by the queen are mainly chosen from areas that were male-dominated in the Middle Ages, for example hunting and fighting. This is to underline Enea's tendency to prefer to spend his time in male company. The fact that people cannot multiply through such behavior also seems unimportant. Also, the relationship between Dido and Eneas is cited only to give an example of the damage Eneas does to women. The queen ignores the heterosexual nature of this connection.

Lavinia’s mother also tries to prevent Virgil’s marriage to Eneas. However, their reasoning is not as sharp as in the medieval novels. She does not accuse Eneas of fornication or cowardice. However, the queen's anger is caused by the goddess Juno, which gives her arguments more emphasis. Virgil puts the charges, which are supposed to defame the masculinity of the Trojan, into the mouths of all male figures. Aeneas is accused by his enemies of being of Phrygian descent, of having well-groomed hair and of being only a "half-man" throughout. The Trojans, according to Turnus' crony Numanus, attracted attention through idleness and excessive personal hygiene. They are accused of behaving like women. Turnus also accuses Aeneas of striving for the appearance of a woman, referring to his handsome hair. However, Turnes does not draw the conclusion that Aeneas would love men because of this. This accusation can only be found in the medieval novels. Indeed, at no time is Aeneas' masculinity really threatened in the eyes of Virgil's audience. Virgil cleverly withdraws authority from all speakers. In this way the charges fall back on themselves. For Virgil's contemporaries, well-groomed hair was by no means evidence of a lack of heroism.

In the Aeneid, masculinity is also equated with fighting strength. Susanne Hafner describes Turnus' behavior on the evening before the duel as follows:

“Turnus invokes his own strength by checking his equipment - weapons, horses, armor - and at the same time trying to defame Aeneas and his masculinity. (...) Turnus surrounds himself with symbols of male fighting power: "

Because Turnus wants to stand out against Eneas with his impressive list, he underlines his own masculinity. The insult that Aeneas was only half a man in behavior suggests that he was not strong at fighting.

The Christian background

Heinrich Christianized the ancient material even more than the Roman d'Eneas. This is particularly evident at the end, in which Veldeke draws a line from the reign of Augustus to the birth of Jesus Christ. Many medieval poets end their work with a Christian thought. This gave her story a moral and could achieve significance for the salvation of the listener's soul. Veldeke emphasizes that the descendants of Eneas also have significance for Christian history. This gives the story of the Trojan a whole new level of relevance.

The journey through the ancient underworld appears in the Eneasroman rather than a journey through Christian hell. Veldeke uses ancient terms like "Elysium" and "Cerberus". Overall, however, Hades is shaped by ideas of hell from medieval Christianity. Torment and repentance are the central themes and the dead souls are dealt with differently depending on the offense. The opposite pole is the beautiful Elysium. Here Veldeke takes a freedom from dogmatic notions of hell, which do not envisage heaven within hell.

In the Aeneid the pagan gods play a major role. This posed a challenge for the medieval poet, as Veldeke on the one hand emphasized the truth of the story, on the other hand had to dismiss the ancient world of gods as pagan. Both he and the audience probably doubted the divine descent of Eneas. So that the poet did not have to bear responsibility for this claim, he referred to Virgil, for whom respect was brought. This is underlined by two subjunctive tones, the Veldeke used in verses 42 and 47. Indeed, Virgil was viewed by many as a pagan prophet who promised the birth of Jesus Christ. Birkhan throws up various options for interpreting the ancient gods in the Eneasroman in a Christian way: The pagan gods can be demonized and depicted as devils. At the same time, however, it is also advisable to use them and their names as allegories of abstract concepts - for example “Venus” instead of “love”. Likewise, veiled truths can be expressed with pagan gods and myths. The possibility of euhemerism makes the gods important people of the past who are only falsely worshiped as gods.

Heinrich keeps antiquity and its gods as a world of its own, but it loses its importance. The deities are not assigned directly to the devil. But they remain impersonal and colorless. Any direct speech on your part is deleted. Only the short episode about the love between Mars and Venus gives both of them some profile.

The role of the gods is greatly reduced compared to the Aeneid. Jupiter's name is mentioned now and then in the novel d'Eneas, for example. In the Eneasroman, however, his role is finally dissolved. The great assembly of the gods in Virgil's Xth book has accordingly been deleted without replacement. Often the intervention of a god is replaced in favor of natural causes or fate. However, the fate does not necessarily appear Christian.

The goddess Venus has a special position. Although it is also portrayed pale and one-dimensional, it causes the love in the novel, which is of paramount importance. [More on this under the section "Minne"] The gods Venus, Amor and Cupid appear in Lavinia’s monologue, and they are given special attention. Rodney Fisher assumes that Heinrich was not overly concerned about introducing classical mythology into the doctrine of medieval Christianity. However, this is especially true of the influential Venus, as F. von Bezold writes:

“Of all the ancient deities, Venus and Cupid managed to survive most permanently and most vividly in the imagination of the Middle Ages. The seductive power of a passion was embodied particularly impressively in their figures. "

A. Decker also confirms that Venus was still considered the goddess of love in the Middle Ages:

"After all, Ms. Venus and her two sons Amor and Cupid had become so familiar to the knightly circles of the Middle Ages that they experienced a kind of cult, at least in the allegorical sense."

In addition, Heinrich also succeeded in conveying Christian moral concepts in his novel. The suicide of Dido makes it clear that this is a reprehensible act. Biblical justification - which is not mentioned in the novel - is commonly the suicide of the traitor Judas, among other things. The dire consequences of sinful greed are also made clear in the novel. Among other things, Camilla and Turnus fall victim to her. [9064–9131] Both die because they have appropriated something foreign. Although Eneas follows the commands of pagan gods [Vv.1958-1958-1994], his godliness is shown very positively. After all, this is the only way his fate can come true. His obedience could well serve as a model for Christians. Furthermore, in a conversation with Lavinia, the queen describes love as eternal, inaudible and invisible. These attributes also apply to God. This assignment is also in the Christian sense, because according to 1 John 4:16 God is love.

Impact history

The Eneasroman was read throughout the Middle Ages without ever being changed much. For a long time it remained the oldest epic in the valid canon of Middle High German poetry. Poets of subsequent generations also praised his work. It was rated as the first “classic” literary epic in German-speaking countries. Gottfried von Strasbourg called Heinrich von Veldeke a “creator of the new art of form” and Wolfram von Eschenbach praised him as a poet of love because of his successful rhetoric. Heinrich was also mentioned by Rudolf von Ems, the poet of "Moriz von Craûn", by Herbort von Fritzlar, Reinbot von Durne, Jocob Püterich von Reichertshausen, as well as in the Göttweiger Trojan War and in the Kolmarer Liederhandschrift.

Heinrich von Veldeke was the first medieval poet to translate a French ancient novel into German. [More on this in the section “Position in the work of the author and the genre” and “The Eneasroman in comparison with the Roman d'Eneas”] Shortly afterwards, Heinrich's model was followed by Herbort von Fritzlar, who wrote an adaptation of the French novel de Troie as a Troy novel Germans made. In addition, there is also the Thebes novel, which has the Roman de Thèbes as a model. It was also written in the middle of the 12th century.

Heinrich's design of the Minne episodes pointed the way for the formation of the early court Venus Minne, which is both magical and compelling.

The detailed and elaborate descriptions in the Eneasroman were imitated by many other poets. So did the regular metric of the verses and the pure rhymes, which were a relatively new phenomenon. In the dialogues, there are many stinging myths that were also imitated. Heinrich tried to use a language that was as supraregional as possible and to balance his dialect. In doing so, he set standards, as subsequent poets such as Herbort von Fritzlar and Albrecht von Halberstadt clearly show.

Last but not least, the novel also provided the nobility, the public, with instructions for elegant behavior, fine clothing and elegant expression. In this respect, too, poetry probably had its effect.

After Heinrich, the Aeneid was never edited for the German audience again. It was not until 1515 that the Franciscan preacher and satirist Thomas Murner translated Virgil's epic verse by verse into German.

literature

Text output

- Virgil: Aeneid. From the Latin by Johann Heinrich Voss. Anaconda Verlag, Cologne 2005.

- Heinrich von Veldeke: Eneasroman. Middle High German / New High German. Translated into New High German from the text by Ludwig Ettmüller . With a commentary and an afterword by Dieter Kartschoke. Revised and bibliographically supplemented edition. Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1986 a. ö. (2004).

Secondary literature

- Helmut Birkhan: History of Old German Literature in the Light of Selected Texts. Part IV. Fiction of the Staufer period. Edition Praesens, publishing house for literature and linguistics, 2003.

- Wolfgang Brandt: Heinrich von Veldeke's narrative concept in the 'Eneide'. A comparison with Virgil's 'Aeneid'. Edited by Josef Kunz, Erich Ruprecht and Ludwig Erich Schmitt. Marburg contributions to German studies. Volume 29. NG Elwert Verlag Marburg, 1969.

- Rodney W. Fisher: Heinrich von Veldeke. Eneas. A Comparison with the Roman d'Eneas and a translation into English. Australian and New Zealand studies in German language and literature. Vol. 17. Peter Lang European Academic Publishers, Bern 1992.

- Alexander Schmitt: Comparison of the voyage under the world in Virgil's Aeneid and the Eneasroman Heinrichs von Veldeke. Grin-Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-640-69673-4 .

swell

Primary literature

- Virgil: Aeneid. From the Latin by Johann Heinrich Voss. Anaconda Verlag, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-938484-08-X .

- Heinrich von Veldeke: Eneasroman . Middle High German / New High German. Translated into New High German from the text by Ludwig Ettmüller. With a commentary and an afterword by Dieter Kartschoke. Revised and bibliographically supplemented edition (= Reclams Universal-Bibliothek , Volume 8303). Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-15-008303-1 .

Secondary literature

- Friedrich von Bezold : The survival of the ancient gods in medieval humanism. Reprint of the 1922 edition. Zeller, Aalen 1962 DNB 450441911 .

- Helmut Birkhan : History of Old German Literature in the Light of Selected Texts. Part IV. Fiction of the Staufer period. Lecture in SS 2003 (= Edition Praesens study books , Volume 9). Edition Praesens, publishing house for literature and linguistics, 2003, ISBN 3-7069-0150-1 .

- Wolfgang Brandt: Heinrich von Veldeke's narrative concept in the 'Eneide'. A comparison with Virgil's 'Aeneid'. Edited by Josef Kunz, Erich Ruprecht and Ludwig Erich Schmitt. (= Marburg contributions to German studies . Volume 29). Elwert, Marburg 1969, ISBN 3-7708-0082-6 (edited dissertation University of Marburg 1967, 346 pages).

- Horst Brunner: History of German literature in the Middle Ages and the early modern period . Extended and bibliographically supplemented edition. Reclams Universal Library 17680, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-15-017680-1 .

- Helmut de Boor: History of German Literature from the Beginnings to the Present. Volume 2. The courtly literature: preparation, flowering, conclusion. 1170-1250. 11th edition. Edited by Ursula Hennig. Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-35132-8 .

- Ernst Robert Curtius : European literature and the Latin Middle Ages . 11th edition, Francke, Bern / Munich 1991, ISBN 3-7720-2133-6 / ISBN 3-7720-1398-8 .

- A. Decker: Contributions to the comparison of Virgil's Aeneide with that of Heinrich von Veldeke. In: Bugenhagen High School Program. 130., Treptow an der Rega 1884.

- Peter Dinzelbacher (Ed.): Non-fiction dictionary of medieval studies. With the cooperation of numerous specialist scholars and using the preparatory work by Hans-Dieter Mück, Ulrich Müller, Franz Viktor Spechtler and Eugen Thurner. Alfred Kröner, Stuttgart 1992.

- M.-L. Dittrich: Heinrich von Veldeke's 'envy'. I. part. Source-critical comparison with the Roman d'Eneas and Virgil's Aeneid. Wiesbaden 1966.

- Volker Mertens , Ulrich Müller (ed.): Epic materials of the Middle Ages (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 483). Kröner, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-520-48301-7 , pp. 247-289.

- Rodney W. Fisher: Heinrich von Veldeke. Eneas. A Comparison with the Roman d'Eneas and a translation into English. Peter Lang European Academic Publishers, Bern 1992 (Australian and New Zealand studies in German language and literature. Vol. 17.).

- Hans Fromm: Heinrich von Veldeke. In: Walther Killy (Ed.): Literaturlexikon. Authors and works of German language. Digital Library Volume 9. Bertelsmann Lexikon Verlag, Berlin 1998.

- Susanne Hafner: Masculinity in courtly narrative literature. Edited by Wiebke Freytag, Nikolaus Henkel, Udo Köster, Hans-Harald Müller, Jörg Schönert, Harro Segeberg. Peter Lang European Science Publishers, Frankfurt am Main 2004 (Hamburg contributions to German studies. Volume 40).

- Joachim Hamm, Marie-Sophie Masse: Aeneas novels. In: Germania Litteraria Mediaevalis Francigena. Volume IV: Historical and Religious Stories. Edited by Geert HM Claassens, Fritz Peter Knapp and Hartmut Kugler. Berlin, New York 2014, pp. 79–116.

- Joachim Hamm: The Poetics of Transition. Telling of the underworld in Heinrich von Veldeke's Eneasroman. In: Underworlds. Models and Transformations. Edited by Joachim Hamm and Jörg Robert. Würzburg 2014, pp. 99–122.

- Winfried Hartmann: Petrus Damianus. In: Hans Dieter Betz et al. (Ed.): Religion in past and present. 4th edition. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2003, ISBN 3-16-146946-1 .

- Peter Kern: Observations on the adaptation process of Virgil's "Aeneid" in the Middle Ages. Translating in the Middle Ages. Cambridge Colloquium 1994. JH et al. Berlin 1996, pp. 109-133.

- Renate Kistler: Heinrich von Veldeke and Ovid. Hermae NF: 71, Tübingen 1993.

- E. North: P. Vergilius Maro Aeneis book. VI. Darmstadt 1970.

- Bernhart Öhlinger: Destructive Unminne. The love-suffering-death complex in the epic around 1200 in the context of contemporary discourses. Edited by Ulrich Müller, Franz Hundsnurscher, Cornelius Sommer . Kümmerle Verlag, Göppingen 2001 (Göppingen work on German studies No. 673.).

- Marion Oswald: Gift and violence: studies on the logic and poetics of the gift in early court narrative literature (= historical semantics , volume 7). Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-36707-4 (Dissertation University of Dresden 2002 372 pages).

- H. Sacker: Heinrich von Veldeke's Conception of the 'Aeneid' . In GLL N, p. 10, 1956/57.

- Silvia Schmitz: The Poetics of Adaptation. Literary inventio in "Eneas" Heinrich von Veldeke. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2007.

- Jean Seznec: The survival of the ancient gods: the mythological tradition in humanism and in the art of the Renaissance , Fink, Munich 1990 (original title: La survivance des dieux antiques, translated by Heinz Jatho), ISBN 3-7705-2632-5 .

Web links