Latvian language

| Latvian (Latviešu valoda) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | about 2 million | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Recognized minority / regional language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

lv |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

lav |

|

| ISO 639-3 | ||

The Latvian language (Latvian latviešu valoda ) belongs to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family . It is the constitutionally anchored official language in Latvia and one of the twenty-four official languages of the EU . Latvian is the mother tongue of around 1.7 million people, most of whom live in Latvia, but also in the diaspora.

general description

Latvian belongs to the eastern group of the Baltic languages ( East Baltic , see subdivision of the Baltic languages ). In its current structure, Latvian is further removed from Indo-European than its related and neighboring Lithuanian . Archaic features, however, can be found in traditional folk songs and poems ( Dainas ), where similarities with Latin , Greek and Sanskrit are more evident. The vocabulary contains many loan words from German , Swedish , Russian and, more recently, from English . Around 250 colloquial words are loanwords from Livonian . With Latvia's accession to the EU and the translation of extensive legal texts, there were gaps in the Latvian vocabulary. The state translation agency checks and develops new words .

Latvian is written using the Latin script. The first grammar of Latvian (Manuductio ad linguam lettonicam facilis) was published in 1644 by Johann Georg Rehehusen , a German. Originally an orthography based on Low German was used, but at the beginning of the 20th century an almost phonematic spelling was introduced in a radical spelling reform . This spelling, which is still valid today, uses some diacritical marks , namely the overline to indicate a long vowel, the comma under a consonant to indicate the palatalization and the hatschek (hook) to generate the characters " Č ", " Š " and " Ž ".

Compared to Western European languages, Latvian is a pronounced inflectional language . There are inflections used and items are omitted. Foreign proper names also have a declinable ending in Latvian (in the nominative -s or -is for masculine, -a or -e for feminine; names ending in -o are not inflected). They are also reproduced phonologically in Latvian spelling (examples are Džordžs V. Bušs for George W. Bush , Viljams Šekspīrs for William Shakespeare ). Many current Latvian surnames that are of German origin also belong to this group and are often barely recognizable in the typeface for Germans. The practice of declination and the phonetic spelling of proper names was enshrined in the Latvian Law on Names of March 1, 1927.

History in the 20th century

With the establishment of the first Latvian state in 1918, Latvian became the state language for the first time. Associated with this was extensive standardization to create a standard language.

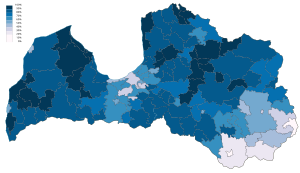

Russification began during membership of the Soviet Union . Through targeted promotion of immigration, Latvian almost became a minority language in the Latvian SSR (in 1990 there were just 51% Latvian speakers in Latvia, in the capital Riga only about 30%). After 1991, drastic measures were introduced to at least partially reverse this situation, which also drew criticism from some western countries. In 2006, 65% of the population of Latvia spoke Latvian as their mother tongue again (88% of the population in total speak Latvian), and all schoolchildren are - at least theoretically - sometimes taught in Latvian in addition to their mother tongue , so that Latvian may return in a few decades will have achieved a status comparable to other national languages in Europe . In the larger cities and especially in the satellite towns that arose during the Soviet era, Russian is used as the most dominant lingua franca , parallel to Latvian.

Since May 1, 2004, Latvian has been one of the official languages of the EU .

Alphabet and pronunciation

The Latvian alphabet consists of 33 characters:

Consonants

| Latvian | IPA | German | example |

|---|---|---|---|

| b | [ b ] | b | b ērns 'child' |

| c | [ ʦ ] | z (like cedar) | c ilvēks 'human' |

| č | [ ʧ ] | ch | č akls 'hardworking' |

| d | [ d ] | d | d iena 'day' |

| f | [ f ] | f | f abrika 'factory' |

| G | [ g ] | G | g ribēt 'want' |

| G | [ ɟ ] | about dj; exactly like the hungarian "gy" | ģ imene 'family' |

| H | [ x ] | ch (as in do) | h aoss 'chaos' |

| j | [ j ] | j | j aka 'jacket' |

| k | [ k ] | k | k akls 'neck' |

| ķ | [ c ] | about tj (as in tja); exactly like Hungarian “ty” or Icelandic pronunciation of kj in Reykjavík |

ķ īmija 'chemistry' |

| l | [ l ] | rather thick l (as in Trakl) | l abs 'good' |

| ļ | [ ʎ ] | lj | ļ oti 'very' |

| m | [ m ] | m | m az 'little' |

| n | [ n ] | n | n ākt 'come' |

| ņ | [ ɲ ] | nj | ņ emt 'take' |

| p | [ p ] | p | p azīt 'know' |

| r | [ r ] | r (tip of tongue-r) | r edzēt 'see' |

| s | [ s ] | voiceless s | s acīt 'say' |

| š | [ ʃ ] | sch | š ince, here ' |

| t | [ t ] | t | t auta 'people' |

| v | [ v ] | w | v alsts 'state' |

| z | [ z ] | voiced s | z ināt 'to know' |

| ž | [ ʒ ] | like g in embarrassment | ž urka 'rat' |

The letters " h " and " f " only appear in foreign or loan words.

The following consonants still appear in older scripts:

- " Ŗ ", a palatalized "R" (mīkstināts burts "R")

- “ Ch ”, understood as a single sound, corresponding to the German “ch”, today written as “h”.

These forms were abolished by the 1946 spelling reform in Soviet Latvia, but continued to appear in exile literature.

Vowels

The phonemes / e / and / æ / write usually equal, as a e (short) or ē (long). The linguist and writer Jānis Endzelīns that of the first independence movement was influenced, used for / æ / ę the letter and / æ: / additionally a Makron. This was and is taken up again and again by supporters of an “extended orthography”.

Originally spoken only as a diphthong o is usually as in modern reclining and foreign words / ɔ / and / o / spoken.

All other vowels are assigned exactly one letter in standard Latvian .

| palatal | velar | uvular | |

|---|---|---|---|

| closed | i | u | ɑ |

| open | e | æ |

| Latvian | IPA | German | example |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | [ a ] | a | a kls 'blind' |

| - | [ aː ] | Ah | ā trs 'fast' |

| e | [ ɛ ] , [ æ ] | ä, sometimes very open ä (as in English has ) | e zers 'lake' |

| ē | [ ɛː ], [ æː ] | uh, sometimes very open ä (like in English bad ) | ē st 'eat' |

| i | [ i ] | i | i lgs 'long' |

| ī | [ iː ] | ih | ī ss 'short' |

| O | [ Uɐ ], [ ɔ ] , [ ɔː ] | in Latvian words uo, in foreign words long or short o | o zols 'oak', [ uɐzuɐls ] (as diphthong), o pera 'opera' (long), o nlain (short) |

| u | [ u ] | u | u guns 'fire' |

| ū | [ uː ] | uh | ū dens 'water' |

The vowels with macron ( i.e. ā, ē, ī and ū ) are pronounced long, whereas the normal vowels are very short, usually barely audible at the end of the word.

The o is spoken in originally Latvian words like [ uɐ ], which as a diphthong cannot be divided into long or short and thus makes a macron superfluous. But even in borrowings, which have long been the central vocabulary include (z. B. oktobris ), will almost always this letter as a simple short vowel [ ɔ ] or [ ɔː spoken]. A counterexample is again mode (fashion, style), where the diphthong is used. Oktobra mode thus contains three differently pronounced o . On the banknotes from the time between the two world wars, the “ Ō ” appears in the foreign word “nōminālvērtībā”. The character was abolished with the spelling reform in 1946. In the Latgale spelling is "Ō" to this day.

In contrast to all other vowels, the long or short pronunciation of the o never forms minimal pairs . The other vowels therefore need the macron to create minimal pairs like tevi 'you' - tēvi 'father'; Rīga 'Riga' - Rīgā 'in Riga' in the spelling.

The stress generally says nothing about the length of the vowels, cf. the section grammar . The grammatically significant distinction between unstressed vowels in long and short is z. B. unknown in German or Russian.

Short, unstressed vowels, especially in the final vowel, are largely de-tuned ( disapproved ) in the popular Riga dialect , e.g. B. bija 'he / she / it was' is pronounced [ bijɑ̥ ] instead of [ bijɑ ], or cilvēki 'people, people' as [ t͡silʋæːki̥ ] instead of [ t͡silʋæːki ]. This sometimes acts like swallowing or dropping these vowels.

Emphasis

In Latvian, the stress is almost always on the first syllable, which could be due to the influence of Livian , a Finno-Ugric language . There are only a few exceptions, for example the phrases labdien (good day) and labvakar (good evening), which are made up of the components lab (s) (good) and dien (a) (day) or vakar (s) (evening ), stressed on the second syllable. Other exceptions from the everyday language, also with emphasis on the second syllable, paldies (thank you) and all with chewing beginning (Somehow) words.

Orthography: examples

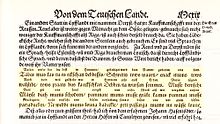

Example 1: Our Father in Latvian and different versions: The original spelling of Latvian was strongly based on the German language. The first attempts with diacritical marks occurred in the 19th century. After Latvia gained independence, there was a sweeping reform that was only reluctantly picked up by the media over the years.

| First orthography ( Cosmographia , 16th century) |

Old orthography (BIBLIA 1848) |

Modern orthography (since 1920) |

Internet style without a Latvian keyboard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Täbes mus kas do es eckſchan debbeſſis, | Muhſu Tehvs debbeſîs | Mūsu tēvs debesīs | Muusu teevs debesiis | |

| Schwetitz tows waartz, | Swehtits lai top taws true | Svētīts lai top tavs vārds | Sveetiits lai top tavs vaards | |

| enack mums tows walſtibe | Lai nahk tawa walſtiba | Lai nāk tava valstība | Lai naak tava valstiiba | |

| tows praats bus | Taws prahts lai noteek | Tavs prāts lai notiek | Tavs praats lai notiek | |

| ka eckſchkan Debbes, ta wurſan ſemmes. | kà debbeſîs tà arirdſan zemes wirsû | kā debesīs, tā arī virs zemes | kaa debesiis taa arii virs zemes | |

| Muſſe deniſche Mäyſe düth must ßchodeen, | Muhsu deeniſchtu maizi dod mums ſchodeen | Mūsu dienišķo maizi dod mums šodien | Muusu dienishkjo maizi dod mums shodien | |

| pammate müms muſſe gräke | Un pametti mums muhſu parradus [later parahdus] | Un piedod mums mūsu parādus | Un piedod mums muusu paraadus | |

| ka meß pammat muſſe parradueken, | kà arri mehs pamettam ſaweem parrahdneekeem | kā arī mēs piedodam saviem parādniekiem | kaa arii mees piedodam saviem paraadniekiem | |

| Ne wedde mums louna badeckle, | Un ne eeweddi muhs eekſch kahrdinaſchanas | Un neieved mūs kārdināšanā | Un neieved muus kaardinaashanaa | |

| pett paſſarga mums nu know loune | bet atpeſti muhs no ta launa [later łauna] | bet atpestī mūs no ļauna | bet atpestii muus no ljauna | |

| Jo tew peederr ta walſtiba | Jo tev pieder valstība | Jo tev pieder valstiiba. | ||

| un tas ſpehks un tas gods muhſchigi [later muhzigi] | spēks un gods mūžīgi | speeks un gods muuzhiigi | ||

| Amen. | Amen | Amen | Aamen |

Example 2: Daina 4124 from the collection of August Bielenstein : This example shows the efforts of the linguist to approximate the notation to a phonetic representation. He differentiates between the voiced " ſ " and the unvoiced "s" . The palatalized consonants “ģ”, “ķ”, “ļ”, “ņ” and “ŗ” are represented by a slash as in “ n ” . The lengthening of all vowels is no longer done by the stretching h, but by an overline . Only the use of “z” instead of “c”, “ee” instead of “ie”, “tsch” instead of “ č ”, “sch” instead of “ š ” and “ſch” instead of “ ž ” shows the influence of German Model.

| Bielenstein 1907 | Transcription 2001 | German | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Came tea kalni, came tās leijas, | Kam tie kalni, came tās lejas, | For whom are the hills, for whom are the lowlands, | |

| Came tea smīdri ōſōli |

Did tie smīdri ozoliņi come? | Who are the slim oaks for? | |

| Rudſim kalni, meeſim leijas, | Rudzim kalni, miezim lejas, | The hills for the rye, the lowlands for the barley, | |

| Bitēm smīdri ōſōli |

Bitēm smīdri ozoliņi. | The slender oaks for the bees. |

grammar

Like all Baltic languages, Latvian is highly inflected , i. H. the shape of a word changes within various grammatical categories according to its grammatical features ( declination , conjugation , comparison ). This is done on the one hand by adding affixes , on the other hand by changing the word stem. These two types of inflection are characteristic of Latvian, the second often being conditioned by the first; In Latvian philology, one speaks of the "conditional" or "non-conditional" phonetic change, which has rather complicated rules. The root of the word can be changed in Latvian both by the ablaut (e.g. pendet - pērku ) and by specific consonant changes (e.g. briedis - brieža, ciest - ciešu ). Holst calls the latter in his grammar standard alternation.

Nouns

With a few exceptions, masculine words always end in -s, -is or -us , feminine words usually end in -a or -e . There are some feminine words that end in -s , e.g. B. govs 'cow' or pils 'castle'. There are also many exceptions in Latvian grammar. With the masculine three or four declination classes are differentiated depending on the point of view, whereby the last only differ in one palatalization and are often considered as one. There are also three or four classes of feminine, with the fourth standing for reflexive verbal nouns and is often considered separately. Neutra do not exist. In addition to the four cases known in German, nominative (Nominatīvs), genitive (Ģenitīvs), dative (Datīvs) and accusative (Akuzatīvs) , there are also locative (Lokatīvs) and traditionally instrumental (Instrumentālis) and vocative (Vokatīvs). The last two cases are usually not specified in a paradigm, as the instrumental is always paraphrased with the substitute construction ar + accusative , the vocative is formed by simply leaving out the -s in masculine or the -š or -a in diminutive . However, the information on the number of cases differs depending on the author, depending on whether or not he recognizes the instrumental and vocative as independent. The figures vary between five and seven. Holst and Christophe assume six cases.

Examples of complete paradigms :

- a 1st class masculine, plus 'friend'

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom | draug s | draug i |

| gene | draug a | draug u |

| Date | Draug on | on it iem |

| Acc | draug u | on it us |

| Instr | ar draug u | ar draug iem |

| Locomotive | draug ā | draug os |

- a 2nd class masculine, brālis 'brother'

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom | brāl is | brāļ i |

| gene | brāļ a | brāļ u |

| Date | brāl im | brāļ iem |

| Acc | brāl i | brā ļus |

| Instr | ar brāl i | ar brāļ iem |

| Locomotive | brāl ī | brāļ os |

- a 3rd class masculine, tirgus 'market'

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom | tirg us | tirg i |

| gene | tirg us | tirg u |

| Date | Tirg to | tirg iem |

| Acc | tirg u | tirg us |

| Instr | ar tirg u | ar tirg iem |

| Locomotive | tirg ū | tirg os |

- a 4th grade masculine, akmens 'stone'

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom | akme ns | akme ņi |

| gene | akme ns | akme ņu |

| Date | akme nim | akme ņiem |

| Acc | akme ni | akme ņus |

| Instr | ar akme ni | ar akme ņiem |

| Locomotive | akme ni | akme ņos |

- a 1st class feminine, osta 'Hafen'

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom | east a | east as |

| gene | east as | east u |

| Date | east ai | east ām |

| Acc | east u | east as |

| Instr | ar ost u | ar ost ām |

| Locomotive | east ā | east ās |

- a second class feminine, egle 'fir'

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom | egl e | egl it |

| gene | egl it | eg ļu |

| Date | egl ei | egl ēm |

| Acc | egl i | egl it |

| Instr | ar egl i | ar egl ēm |

| Locomotive | egl ē | egl ēs |

- a 3rd grade feminine, sirds 'heart'

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom | sird s | sird is |

| gene | sird s | sir žu |

| Date | sird ij | sird īm |

| Acc | sird i | sird is |

| Instr | ar sird i | ar sird īm |

| Locomotive | sird ī | sird īs |

- a 4th grade feminine, iepirkšanās '(the) shopping'

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom | iepirkšan ās | - |

| gene | iepirkšan ās | - |

| Date | - | - |

| Acc | iepirkšan os | - |

| Instr | ar iepirkšan os | - |

| Locomotive | - | - |

Question pronomina

| Question word | (Jautājuma vārds) | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom | who? What? | cheese? |

| gene | whose? | kā? |

| Date | whom? | came? |

| Acc | whom? What? | ko? |

| Instr | with who? by which? | ar ko? |

| Locomotive | Where? | short? |

Verbs

Like German, Latvian has six tenses: present (tagadne) , imperfect (pagātne) , perfect (saliktā tagadne) , past perfect (saliktā pagātne) , future I (nākotne) and future II (saliktā nākotne) . The three tenses present, past tense and future tense I are formed by conjugating the respective verb. Perfect, past perfect and future tense II are so-called compound tenses , which are formed with the past participle active and the auxiliary verb būt 'sein' in the appropriate form.

The verbs of the Latvian language can be divided into three conjugation classes.

- Verbs in the first conjugation have a monosyllabic infinitive (not including prefixes) that ends in -t . The verbs in this class are conjugated very inconsistently.

- Verbs of the second conjugation end in -ēt , -āt , -īt or -ināt in the infinitive . Your infinitive is usually two-syllable (without prefixes), the first person singular present tense has just as many syllables.

- Verbs of the third conjugation are similar to those of the second. They end in -ēt , -āt , -īt or -ot in the infinitive . You have one more syllable in the first person singular present tense than in the infinitive.

The three so-called irregular verbs būt 'sein', iet 'go' and dot 'give' do not belong to any conjugation class.

In the third person , the endings for singular and plural are always the same for all verbs.

The indicative active of the auxiliary verb būt 'sein':

| Present tense (tagadne) | Past tense (pagātne) | Future tense I (nākotne) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ps. Sg. | it | esm u | bij u | būš u |

| 2. Ps. Sg. | do | it i | bij i | būs i |

| 3rd Ps. Sg. | viņš / viņa | ir | bij a | bus |

| 1. Ps. Pl. | mēs | it on | bij ām | būs im |

| 2nd Ps. Pl. | jūs / jūs | it at | bij āt | būs it |

| 3rd Ps. Pl. | viņi / viņas | ir | bij a | bus |

The indicative active of a verb of the first conjugation, kāpt 'climb':

| Present tense (tagadne) | Past tense (pagātne) | Future tense I (nākotne) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ps. Sg. | it | kāpj u | kāp u | kāpš u |

| 2. Ps. Sg. | do | kāpj | kāp i | kāps i |

| 3rd Ps. Sg. | viņš / viņa | kāpj | kāp a | kāps |

| 1. Ps. Pl. | mēs | kāpj am | kāp ām | kāps im |

| 2nd Ps. Pl. | jūs / jūs | kāpj at | kāp āt | kāps it |

| 3rd Ps. Pl. | viņi / viņas | kāpj | kāp a | kāps |

The indicative active of a verb of the second conjugation (subclass 2a), zināt ' to know':

| Present tense (tagadne) | Past tense (pagātne) | Future tense I (nākotne) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ps. Sg. | it | interest u | zināj u | zināš u |

| 2. Ps. Sg. | do | interest i | zinā i | zinās i |

| 3rd Ps. Sg. | viņš / viņa | interest a | zināj a | zinās |

| 1. Ps. Pl. | mēs | zin ām | zināj ām | zinās im |

| 2nd Ps. Pl. | jūs / jūs | zin at | zināj āt | zinās it |

| 3rd Ps. Pl. | viņi / viņas | interest a | zināj a | zinās |

The indicative active of a verb of the second conjugation (subclass 2b), gribēt 'will':

| Present tense (tagadne) | Past tense (pagātne) | Future tense I (nākotne) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ps. Sg. | it | grib u | gribēj et al | gribēš u |

| 2. Ps. Sg. | do | grib i | gribēj i | gribēs i |

| 3rd Ps. Sg. | viņš / viņa | grib | gribēj a | gribēs |

| 1. Ps. Pl. | mēs | grib on | gribēj ām | gribēs im |

| 2nd Ps. Pl. | jūs / jūs | grib at | gribēj āt | gribēs it |

| 3rd Ps. Pl. | viņi / viņas | grib | gribēj a | gribēs |

The indicative active of a verb of the third conjugation mazgāt 'wash':

| Present tense (tagadne) | Past tense (pagātne) | Future tense I (nākotne) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ps. Sg. | it | mazgāj u | mazgāj u | mazgāš u |

| 2. Ps. Sg. | do | mazgā | mazgāj i | mazgās i |

| 3rd Ps. Sg. | viņš / viņa | mazgā | mazgāj a | mazgās |

| 1. Ps. Pl. | mēs | mazgāj am | mazgāj ām | mazgās im |

| 2nd Ps. Pl. | jūs / jūs | mazgāj at | mazgāj āt | mazgās it |

| 3rd Ps. Pl. | viņi / viņas | mazgā | mazgāj a | mazgās |

prepositions

It is noteworthy that prepositions in the plural generally rule the dative , even if they require a different case in the singular (e.g. pie 'bei' always has the genitive). “With the friend” therefore means pie drauga , but “with the friends” means pie draugiem .

Language example

Universal Declaration of Human Rights , Article 1:

- Visi cilvēki piedzimst brīvi un vienlīdzīgi savā pašcieņā un tiesībās. Viņi ir apveltīti ar saprātu un sirdsapziņu, un viņiem jāizturas citam pret citu brālības garā.

- All people are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should meet one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Dialects

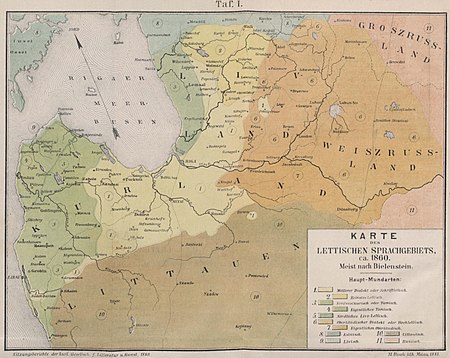

The Latvian dialects were already thoroughly examined by August Bielenstein . Alfrēds Gāters devoted a great deal of space to this topic in his book on the Latvian language. In detail there are different views on the grouping of the Latvian dialects. In general, the varieties of the Latvian language are divided into three main groups. The subdivision corresponds to the map:

-

Tahmisch (Lībiskai dialect)

- Curonian-Tahmic dialects (Kurzemes izloksnes)

- Deep Tahmisch in Northern Courland (Kurzemes dziļās / tāmnieku)

- Shallow Tahmisch in Central Courland (Kurzemes nedziļās)

- Livonian-Tahmic dialects (Vidzemes izloksnes)

- Curonian-Tahmic dialects (Kurzemes izloksnes)

- Middle Latvian (Vidus dialekts)

- Livonian Central Latvian (Vidzemes izloksnes)

- Zemgallian Middle Latvian (Zemgaliskās izloksnes)

- Semgallic with anaptyxe ( scion vowel ) (Zemgaliskais ar anaptiksi)

- Semgallic without anaptyxes (Zemgaliskais bez anaptiksi)

- Curonian-Middle Latvian dialects (Kursiskās izloksnes)

- Zemgallian-Curonian Middle Latvian dialects (Zemgaliskās-Kursiskās izloksnes) in the south of Kurland.

- High Latvian (Augšzemnieku dialect)

- High Latvian Latgallens (Nesēliskās / latgaliskās izloksnes)

- Deep High Latvian (Nesēliskās dziļās)

- Transitional dialects to Middle Latvian (Nesēliskās nedziļās)

- Selic dialects of High Latvian (Sēliskās izloksnes)

- Deep Selish dialect (Sēliskās dziļās)

- Shoal selische dialect (Sēliskās nedziļās)

- High Latvian Latgallens (Nesēliskās / latgaliskās izloksnes)

Low Latvian (Lejzemnieku dialekts) is occasionally used as a combination of Tahmisch and Middle Latvian and complementary to High Latvian (Augšzemnieku dialekts). The term "High Latvian" does not have the meaning of "Official Latvian". There is currently a written language in Latvia that is closely based on the Central Latvian dialects around the capital Riga. Latgalian is also used as a regional written language .

The terms Courland and Livonia have only a limited relationship to the Curonian and Liv dialects.

The Tahmisch is very influenced by the Livian language , which is hardly spoken today and belongs to the Finno-Ugric language family . Semgallic is derived from the Semgallic . The Selon or Selenian people lived in historical Selonia and are represented today by the Selon dialects. Latgalian is spoken by the Latgals . In the Middle Ages, the northern cures in Courland approximated their language to Central Latvian. Middle Latvian developed out of contact with the neighboring Semgallic and West Latgalian dialect groups.

Another language closest to Latvian, sometimes also classified as a Latvian dialect, is the Spit Curonian , which goes back to fishermen from Kurland who settled in the 14th – 17th centuries. Century spread along the Lithuanian and Prussian coast to Danzig . Since the 19th century there had been many speakers on the Curonian Spit , almost all of whom fled to the west during the Second World War, where at the beginning of the 21st century only a few very old people could speak the language.

literature

- V. Bērziņa-Baltiņa: Latviešu valodas gramatika . America's Latviešu Apvienība, New York 1973.

- August Bielenstein : The Latvian language, according to its sounds and forms . Reprint of the Berlin edition: Dümmler, 1863-64 (2 volumes) edition. Central antiquariat of the GDR, Leipzig 1972.

- August Bielenstein : The Limits of the Latvian Tribe and the Latvian Language in the Present and in the 13th Century . Reprint of the St. Petersburg edition: Eggers, 1892 edition. v. Hirschheydt, Hannover-Döhren 1973, ISBN 3-7777-0983-2 .

- Valdis Bisenieks, Izaks Niselovičs (Red.): Latviešu-vācu vārdnīca . Avots, Riga, 2nd edition 1980 (Latvian-German dictionary).

- Bernard Christophe: Kauderwelsch 82, Latvian word for word . 5th edition. Reise Know-how Verlag Peter Rump GmbH, 2012, ISBN 978-3-89416-273-3 .

- Berthold Forssman: Labdien !, Latvian for German speakers - Part 1 . Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2008, ISBN 978-3-934106-59-8 .

- Berthold Forssman: Labdien !, Latvian for German speakers - Part 2 . Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2010, ISBN 978-3-934106-74-1 .

- Berthold Forssman: Latvian Grammar . Publishing house JH Röll, Dettelbach 2001.

- Alfrēds Gāters: The Latvian language and its dialects . Mouton / de Gruyter, The Hague, Paris, New York 1977, ISBN 978-90-279-3126-9 .

- Jan Henrik Holst : Latvian grammar . Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-87548-289-1 .

- Lidija Leikuma / Ilmārs Mežs: Viena zeme, vieni ļaudis, nav vienāda valodiņa. Latviešu valodas izlokšņu paraugi (with 105 dialect samples on 3 CDs) . Upe tuviem un tāliem, Riga 2015.

- Daniel Petit: Studies on the Baltic languages . Koninklijke Brill, Leiden 2010, ISBN 978-90-04-17836-6 .

- Ineta Polanska: On the influence of Latvian on German in the Baltic States . Dissertation at the Otto Friedrich University . Bamberg 2002.

- Dace Prauliņš: Latvian: An Essential Grammar . Routledge, London 2012, ISBN 978-0-415-57692-5 .

- Christopher Moseley , Dace Prauliņš: Colloquial Latvian: The Complete Course for Beginners (Colloquial Series) . Routledge, 2015, ISBN 9781317306184 .

- Aija Priedīte, Andreas Ludden and Wilfried Schlau: Latvian intensive !: The textbook of the Latvian language . 2nd Edition. Bibliotheca Baltica, Hamburg 2002.

- Anna Stafecka: Latviešu valodas dialekti (with numerous dialect samples) . in: Latvieši un Latvija , Volume 1: Latvieši . Latvijas zinātņu akademija, Riga 2013, ISBN 978-9934-81149-4 .

Web links

- Latvian ↔ German online dictionary in Universal dictionary

- Mother tongue as identity and livelihood of small peoples - an essay by Māra Zālīte

- Entry on Latvian in the Encyclopedia of the East / University of Klagenfurt. (PDF; 365 kB)

- Aina Urdze: Case study: Latvian language communities in the diaspora in the FRG (PDF; 863 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/PDF-Publikationen/a871-die-laender-europas.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=10

- ↑ Gyula Decsy: Introduction to the Finno-Ugric linguistics. Wiesbaden 1965, p. 77.

- ↑ Detlef Henning: The German ethnic group in Latvia and the rights of minorities 1918 to 1940 . In: Boris Meissner , Dietrich André Loeber , Detlef Henning (eds.): The German ethnic group in Latvia during the interwar period and current issues of German-Latvian relations . Bibliotheca Baltica, Tallinn 2000, ISBN 9985-800-21-4 , pp. 40–57, here p. 50.

- ↑ Exhibition on the 100th anniversary of the death of August Bielenstein Jānis Stradiņš emphasized in his lecture the importance of this map for defining the borders.

- ↑ a b after Holst , p. 37

- ↑ after Holst, p. 45

- ↑ Gyula Decsy: Introduction to the Finno-Ugric Linguistics 78, pp Wiesbaden 1965

- ↑ Sebastian Münster : Cosmographei or description of all countries, rulers, Fürnemsten Stetten, stories, customs, handling etc. First described by Sebastianum Munsterum, also improved by himself, of world and natural histories, but now bit on the MD LXI. jar according to the contents of the following sheet description veil increased. Basel, 1561, S. mclxviij [1168]

- ↑ BIBLIA, published in Riga, 1848 (reprint of the 1739 edition)

- ↑ August Bielenstein: The wooden structures and wooden tools of the Latvians , St. Petersburg 1907, page 186

- ↑ Augusts Bīlenšteins: Latviešu koka celtnes , Riga 2001, p. 176

- ^ According to Holst, pages 99 to 101

- ↑ After Forssman: Labdien! , P. 22.

-

↑ After Holst, p. 106.

After Christophe, pp. 65–67. - ^ According to Julius Döring: About the origin of the Kurland Latvians . (with 2 plates) in reports of the meeting of the Courland Society for Literature and Art , 1880

- ↑ After August Bielenstein: Atlas of the ethnological geography of today's and prehistoric Lettenland . Kymmel Publishing House , St. Petersburg 1892.

- ↑ The Latvian dialects of the present. Isogloss card . In: Bielenstein (1892/1973)

- ↑ Gater (1977).

- ↑ Petit (2010), page 44

- ↑ Polanska (2002), page 14

- ^ Andreas Kossert : East Prussia: Myth and History. Munich 2007, pp. 190–195.