Livonian language

| Liv (LiVO KEL) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Latvia | |

| speaker | extinct since 2013 | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | - | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

fiu (other Finnish-Ugr. languages) |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

liv |

|

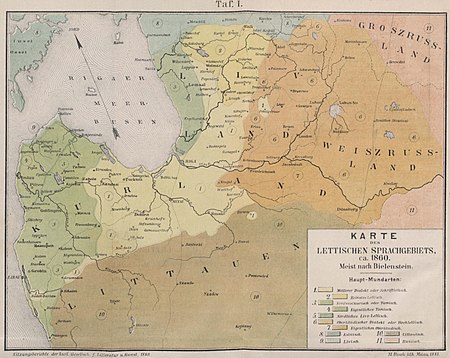

Liv (Livo Kel, also rāndakēļ) was from the people of Liven in the Latvian province of Kurzeme ( . Lett Kurzeme ) spoken words on the peninsula, the Gulf of Riga is separated from the Baltic Sea. As the name suggests, it used to be spoken in Livonia ; there, however, the language has long since died out.

general description

Livish belongs to the Finno-Ugric languages and has the typical characteristics of this language family , e.g. B. a pronounced case system . It is most closely related to Estonian , from which it has taken around 800 loanwords. However, during the long isolation among a Latvian-speaking population, it also adopted around 2000 loanwords and other elements of Latvian . About 200 loanwords come from German , for example job titles such as Dišler (German carpenter ), Slakter (German butcher ) and Aptēkõr (German pharmacist ) as well as terms from trade and craft such as B. tsukkõr (dt. Sugar ) and dreibenk (dt. Lathe ).

Not to be confused with the Livvian language , also called Olonetzisch, another Baltic Finnish language that is still spoken in Karelia today.

alphabet

The Liv language has 45 graphemes :

a A, ā Ā, ä Ä, ǟ Ǟ, b B, d D, ḑ Ḑ, e E, ē Ē, f F, g G, h H, i I, ī Ī, j J, k K, l L , ļ Ļ, m M, n N, ņ Ņ, o O, ō Ō, ȯ Ȯ, ȱ Ȱ, (ö Ö), (ȫ Ȫ), õ Õ, ȭ Ȭ, p P, r R, ŗ Ŗ, s S, š Š, t T, ț Ț, u U, ū Ū, v V, (y Y), (ȳ Ȳ), z Z, ž Ž

The graphemes listed in brackets are only used for the correct representation of proper names. Due to the technical requirements, the representation of the listed graphemes on typewriters and computers is difficult. It can therefore also be found in online publications in which <ķ> is represented as <k '>. While the cedilla can be called up via the Latvian keyboard, difficulties arise especially with the graphemes with two diacritical marks ( trema and macron ). The macron of the long vowel <ǟ> is replaced by an underscore and represented as < ä >.

According to Michael Everson , the letters "ḑ Ḑ ļ Ļ ņ Ņ ŗ Ŗ ț Ț" should be written with a comma below (not with cedilla or even Ogonek ). The Unicode names of the letters »ḑ Ḑ ļ Ļ ņ Ņ ŗ Ŗ« contain the addition WITH CEDILLA, although they are shown in the code tables with a comma below. Only in the case of T does Unicode explicitly differentiate between the two diacritics cedilla and comma below.

phonetics

Phonetic peculiarities

Like the other Finno-Ugric languages, Livic has an almost continuous stress on the first syllable of the word. The quantity distinctions that occur in both vowels and consonants are also characteristic. The length of the vowels makes a difference both morphologically and semantically .

The presentation of the phonetic peculiarities of the Liv language is made more difficult by the fact that the most detailed investigations were carried out before the Second World War. Since then, the Livonian language has changed significantly due to significant events (World War II, the occupation by the Soviet Union and the resulting flight).

Suprasegmental

intonation

The main accent of Liv words is almost exclusively on the first syllable. A secondary accent may occur with semi-long vowels. However, this can only fall on the second or fourth syllable.

The sentence accent is determined by the intention to speak.

Melodization

Livian has three basic intonation patterns (within a syllable):

- stretched intonation

- falling intonation

- pushed intonation

With stretched intonation , the tone rises towards the end of the syllable and then falls slightly again. Kettunen also characterizes this intonation as slightly interrogative or progressive , with the latter predominantly occurring within the word. Similar to Latvian, stretching is represented by a tilde . Example:

- uõla ( Eng . "egg")

- sīlma ( Eng . "eye"); but shown here as an overly long vowel without a tilde

The falling intonation begins with a stronger tone, which then weakens. Characteristic here is a steady rise followed by a steady fall in the same length. Phonetically, this intonation is represented by a grave accent. Example:

- strèbt ( Eng . "slurp")

The shock intonation was probably caused by Latvian influences. A tone rises sharply, there is a collision with an abrupt fall of the tone. The length is divided into two parts. The impact intonation is represented phonetically by a circumflex . Example:

- rîts ( Eng . "morning")

With regard to the intonation of sentences, the Livian knows:

- interrogative

- progressive

- terminal

These patterns largely correspond to the intonation in German. Differences that have not been discussed so far exist in the melody of a linguistic act.

Coarticulation

The Liv language shows a regressive assimilation , but also cases of progressive and bilateral assimilation . The assimilation processes mostly find their way into the typeface. The Liiv written language, especially its orthography, was never really fixed and is therefore characterized by a phonetic spelling. The assimilation processes can mainly be traced back to a diachronic view in which a potential original language serves as the basis.

The regressive assimilation can be observed above all in relation to the voicing : Original Lenis sounds became Fortis sounds. This assimilation occurs when an unvoiced consonant follows a voiced consonant:

- juoptõ ( Eng . "drank"): the grapheme <b> became <p>

The progressive assimilation occurs among other things, when a Lenis-According to a follow Fortis Loud and former becomes a Fortis According to:

- sōpkõd ( Eng . "boots"): <k> was originally <g> here

Furthermore, this form of assimilation also occurred with consonant combinations like <lv> and <lj>, whereby the former became a long L-sound [lː], the latter a long, palatalized L-sound [lʼ].

In double-sided assimilation , the voiced consonant environment influenced the voicing of the enclosed fortis sound. <k, p, t> became <g, b, d> in corresponding cases.

Furthermore, final voicings occur in Livic . In phonetic treatises this phenomenon is represented with small print capital letters (e.g. sōpkõd (boots): sōpkõ D ).

Segmental

Vowels

Monophthongs

The Livic counts eight monophthongs , each of which can occur in four quantities, three of which have a distinctive character,

- over short (represented by a superscript vowel)

- short (represented by a simple vowel): m ä gud (mountains)

- half length (represented by a grave accent): m ì ez (man)

- extra long (represented by the macron also shown graphically ): j ā lga (leg)

In contrast to Finnish, Livian has no vowel harmony and in this respect is similar to Estonian. A specialty is the graphematic <õ> represented sound [ɤ], which is represented in Estonian, but not in the other Finno-Ugric languages.

| front | central | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| closed | i | ɤ | u |

| half open | e | ɵ | O |

| open | æ | a |

Diphthongs

With twelve diphthongs, Livic is rich in diphthongs compared to German , but relatively poor compared to other Finno-Ugric languages. The Liv diphthongs correspond to their written implementation in terms of sound, so there are no differences as in German (cf. German: <eu> = [ɔ̯ɪ] as in Europe ).

Consonants

The Livonian language has 23 consonants with the following distinctive features :

- Articulation point

- Articulation and overcoming mode

- Distinction of the quantity

- Hardness

- Voting participation

| bilabial |

labio- dental |

alveolar |

alveolar palatalized |

post- alveolar |

palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p b | t d | tʲ dʲ | k g | ||||

| Nasals | m | n | nʲ | ( ŋ ) | ||||

| Vibrants | r | rʲ | ||||||

| Fricatives | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | H | ||||

| Approximants | j | |||||||

| Lateral | l | lʲ |

In contrast to the German equivalents, the Livonian Fortis plosives are not aspirated. The grapheme <s> is generally articulated voiceless. Another fundamental difference to German consonantism is the palatalization. However, only / d, l, n, r, t / can appear in this form. Palatality is represented graphematically by cédille and phonetically by an apostrophe :

- ud'a (rod for pushing boats on lakes)

- suol ' (intestine)

It should also be noted that there is no uvular [h] in Livic. The intermediate sound that occurs instead, which is located in the area between the German sounds [x] ( Ach-Laut ) and [ç] ( Ich-Laut ), rarely occurs. It has disappeared in the development process of language or has been replaced both graphematically and phonetically by <j> and <v>. Example:

- reja (rake) ( cf.Estn .: reha )

While the quantity of vowels in the typeface is represented by a and ā , for example , and the length is marked by a diacritical mark, double consonants on the consonant side stand for a higher quantity. However, this feature does not apply to consonants in the wording.

status

Livisch died out in 2013. The language was previously limited to twelve villages on the northern Latvian coast of the Ventspils and Talsi counties . The villages to the west of Mazirbe (Livisch: Īra) had a dialect that was closest to Old Livonian , while the villages to the east of einenra had a dialect that was more different from the original language. Īra itself was characterized by a mixed form of both dialects. However, due to developments since the middle of the 20th century, a merging of the dialects was observed. As early as the 19th century, the Salis-Liv dialect (also Livonia- Livian ) died out.

The Livs are recognized as a national minority in Latvia (entry in the passport).

Valts Ernštreits has taught Livish at the University of Riga since 2005 . He edited a collection of poems in the Liv language and a Latvian-Livisch-English dictionary. In 1939 a Livisch-German dictionary was published.

History of the Liv language

The fact that there is no change of level and no vowel harmony in Livonian - as well as in Wepsi - could be an indication that the Livs lived on the edge of the Baltic Finnish-speaking area and separated relatively early as an independent tribe from the related tribes.

As recently as the 19th century, an estimated 2,000 people spoke Livish. Various historical events ultimately led to the language becoming extinct:

- The Livs originally settled in almost all of what is now Latvia west and north of the Daugava and in southern Estonia up to Lake Peipus and the Pärnau estuary. Hence, the Latvian names of many places - e.g. B. Jelgava and Talsi , many rivers (e.g. Gauja ) and lakes (e.g. Usma Lake and Valguma Lake), which are outside of today's Liv language area, of Liv origin. In the 10th to 11th centuries, the Livs were tribute to the Russian Prince of Polotsk, at which time they were first mentioned in a document. At that time the language hardly differed from South Estonian.

- Resistance to the incursions of the Germans who Christianized the Livs from around 1180: Around the year 1200 the Teutonic Order and the Livonian Order ( Order of the Brothers of the Swords ) conquered Livonia . German knights received property in Livonia and settled there. Since then, more and more German loanwords have been included in the Livonian language. Conflicts ensued between the Bishop of Riga and the Order. The oldest written evidence of the Livonian language - mostly proper names - can be found in Latin documents from the 13th and 14th centuries.

- Livonia had around 30,000 Livish speakers in the 13th century (Vääri estimate, 1966).

- 1522: Introduction of the Reformation . The first book in Livisch, a Lutheran mass, was printed in Germany in 1525 and later confiscated so that it has not been preserved. However, the Lutheran Church used the Latvian language from the start, not the Liv language. Numerous Latvian terms from the area of religion, church, etc. were subsequently adopted into Livic. Around this time, the dative on -n, which is very untypical for a Baltic Finnish language, and the Latvian prefixes aiz- and iz-, as well as the suffixes -ig, -om and ib-, could have been adopted from Latvian into Livic .

- 1557: Russian invasion; Dissolution of the remaining Teutonic Order state

- 1558–1583: Livonian War of the Russian Tsarist Empire against Sweden, Denmark and Poland-Lithuania

- 1721: Peace of Nystad . Livonia becomes one of the three Baltic Sea provinces (Estonia, Livonia, Courland) of Tsarist Russia. From this time onwards, various Russian expressions were also taken over as loan words in Livic, e.g. B. The Russian word ulica (street) became Liv uliki .

- 1795: Third partition of Poland . Courland becomes a province of Tsarist Russia.

- In 1846, the linguist Andreas Johan Sjögren found only 22 Liv speakers in the province of Livonia. They lived at the mouth of the Salaca River, not far from today's Estonian-Latvian border. He wrote a "Livian grammar and language form" and a "Livisch-German and German-Livisch dictionary" - both appeared in 1861 - and was the first to develop an orthography for the Livonian language. Since the Livs on the coast of Kurland lived relatively isolated from the Latvians and had strong contacts with the Estonian population on the island of Saaremaa , the Livonian language was able to last longer there. The oldest surviving Liv book was printed in 1863 using the orthography developed by Sjögren . In 1888 there were 2929 Livs.

- 1918: Latvia was founded. In 1925, statistics from the Latvian government gave the number of Livs at 1238. More recent heyday of the Livic. About 50 different books - church hymn books, calendars, etc. a. - were published in Livish. The hectographed magazine Līvli, the spelling of which was based on the East Livian dialect, appeared from 1931 to 1939, and the number of Livs in Courland was estimated at 800–1000 in 1938.

- Second World War and the Soviet Union : Marginalization of the Livic.

- In Latvia, which has been independent since 1990, Livish is officially recognized as a minority language. According to a report in the British Times , the last native Livish speaker died in 2013.

See also

Min izāmō - the national anthem of the Livs.

literature

- Lauri Kettunen: Studies on the Liv language. Eesti Vabariigi Tartu Ülikooli Toimetused. Vol. 8.3. Tartu 1925.

- Lauri Kettunen: Livian dictionary with grammatical introduction. Lexica Societatis Fenno-Ugricae. Vol. 5. Helsinki 1938.

- Johanna Laakso: Declining Dictionary of Livonian, based on Lauri Kettunen's Livonian dictionary . Lexica Societatis Fenno-Ugricae. Vol. 5.2. Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura , Helsinki 1988. ISBN 951-9403-20-5

- Oskar Loorits: Folksongs of the Livs. Learned Estonian society. Vol. 28. Mattiesen, Tartu 1936.

- Lauri Posti: Basics of the Livonian sound history. Helsinki 1942.

- Fanny de Sivers: Parlons live. Editions l'Harmattan, Paris 2001. ISBN 2-7475-1337-8

- Anders Johan Sjögren: Livian Dictionary. Livian grammar. Collected writings Vol. 2. Ed .: F. J. Wiedemann. Imperatorskaya Akademija Nauk. Eggers, St. Petersburg 1861, 1868, Zentralantiquariat, Leipzig 1969 (reprint).

- Tor Tveite: The Case of the Object in Livonian. A corpus based study . Castrenianumin toimitteita, Helsinki 2004. ISBN 952-5150-73-9

Web links

- Extensive list of links

- Trilingual Estonian-Russian-English site about the Livs

- Articles livischer history in Central Europe Review (English)

- Ethnologue report for Livisch

- Latviešu-lībiešu-angļu sarunvārdnīca Trilingual Latvian-Livonian-English page with pronunciation, grammar, idioms and dictionary

- Entry on the Liv language in the Encyclopedia of the European East (PDF; 109 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Last speaker died in 2013 . Ethnologue on Livic; accessed on March 21, 2016.

- ↑ Gyula Decsy: Introduction to the Finno-Ugric linguistics. Wiesbaden 1965, p. 82.

- ^ Fanny de Sivers: Parlons live. Paris 2001, p. 106.

- ↑ Latvian-Livish-English phrasebook ( memento of the original from January 23, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF).

- ↑ The Alphabets of Europe, Version 3.0 (with reference to other sources).

- ↑ After proceedings of the Courland Society for Literature and Art, the 1880th

- ↑ Arvo Laanest: Introduction to the Baltic Finnish languages. Hamburg 1982, p. 35.

- ↑ Gyula Decsy: Introduction to the Finno-Ugric linguistics. Wiesbaden 1965, p. 75.

- ↑ Gyula Decsy: Introduction to the Finno-Ugric linguistics. Wiesbaden 1965, p. 78.

- ↑ Gyula Decsy: Introduction to the Finno-Ugric linguistics. Wiesbaden 1965, p. 77.

- ↑ Gyula Decsy: Introduction to the Finno-Ugric linguistics. Wiesbaden 1965, p. 79.

- ↑ Death of a language: last ever speaker of Livonian passes away aged 103 .

Remarks

- ↑ This representation, in which the tilde is used for phonetic clarification, should not be confused with the graphematic representation <õ>. The phonetic representation is the sound [o], the graphematic one is the sound [ɤ].