Etruscan script

The Etruscan script is the script of the Etruscan language . It was used by the Etruscans in the 7th century BC. Until the assimilation by the Romans in the 1st century BC. Written in a variant of the old Italian alphabet . The writing developed from a western Greek alphabet and was written with mirror-inverted letters from right to left.

The Etruscan numeral was created around 100 years later.

Formation of the writing

With the founding of Pithekussai on Ischia and of Kyme (lat. Cumae ) in Campania as part of the Greek colonization in the 8th century BC. The Etruscans came under the influence of Greek culture . The Etruscans took over an alphabet from the western Greek colonists that came from their homeland, the Euboean Chalkis . This alphabet from Cumae is therefore also known as the Euboean or Chalcidian alphabet. The oldest written documents of the Etruscans date from around 700 BC. Chr.

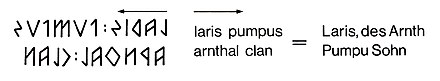

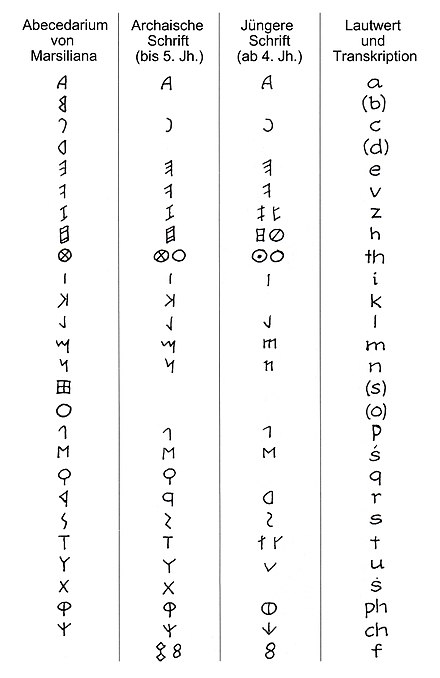

One of the oldest Etruscan writings is on the writing tablet of Marsiliana d'Albegna from the hinterland of Vulci , which is now kept in the National Archaeological Museum of Florence . In this wax tablet of ivory a West Greek model alphabet is inscribed on the edge. According to the later Etruscan writing habits, the letters in this model alphabet were mirrored and arranged from right to left:

The Etruscans did not use all the letters of the model alphabet, as some sounds did not appear in the Etruscan language . These included the letters Beta , Delta , Omicron and the corresponding sounds B, D and O. The Etruscan did not know the sound G either, the letter Gamma was adopted as the character for a K sound. It is noteworthy that the Etruscans did not articulate the voiced stops B, D and G , but the corresponding unvoiced stops P, T and K did. The Etruscans also did not use the letter Samech , which came from the Phoenician script and had the shape of a window.

Since the Etruscan language apparently had more sibilants , one needed more corresponding characters for S-sounds like the Μ and the Χ. The letter M corresponds to the Phoenician letter Sadéh or Zade and probably stands for a Sch sound . The Greeks also used the Phoenician alphabet when developing their characters. This letter, which is often transcribed as Ś, was mainly used in northern Etruria. The X was probably also pronounced as a Sch sound and was mostly common in southern Etruria. The X could also have corresponded to the double consonant KS, as in Latin.

The Etruscans differentiated between an aspirated TH and a voiceless T. The letter in the form of a mirror-inverted F, which is transcribed with V, was spoken bilabially like an English W. The penultimate letter Φ was not pronounced like an F, but as an aspirated P as in early ancient Greek . The last letter Ψ, which is transcribed as CH, probably stands for an aspirated K.

Spread of the Scriptures

The writing with these letters was first used in southern Etruria around 700 BC. In the Etruscan Cisra (Latin Caere ), today's Cerveteri . The writing quickly reached Central and Northern Etruria. From there the alphabet spread from Volterra (Etr. Velathri ) to Felsina , today's Bologna , and later from Chiusi (Etr. Clevsin ) to the Po Valley. In southern Etruria, the script spread from Tarquinia (Etr. Tarchna ) and Veji (Etr. Veia ) further south to Campania, which was controlled by the Etruscans at that time.

Further development of the font

Initially, the Etruscans used three letters for K sounds, which the Romans adopted as C, K and Q in their alphabet. A K was placed in front of the vowel A, a Q in front of a U and the letter C in front of the vowels E and I. Later, the use of the K became established in the North Etruscan cities, whereas the C was preferred in the South Etruscan cities. From the 4th century onwards, the use of the C became common, the letters K and Q were no longer used.

In Etruscan there was apparently a stronger differentiation between fricative structures , as the Etruscans added an F sound in the form of an 8 to their alphabet and added it to the end of the alphabet. The Etruscans adopted the character 8 from the Lydian script . This letter was probably introduced in the 6th century. Before that, the Etruscans had apparently used the spelling VH to denote an F sound. For example, there is the early Etruscan spelling Thavhna for chalice, which later changed to Thafna with 8 for F. In the 6th century BC The Etruscan script finally comprised 23 letters.

| Early Etruscan alphabet | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letter |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| transcription | A. | C. | E. | V | Z | H | TH | I. | K | L. | M. | N | P | Ś | Q | R. | S. | T | U | Ś | PH | CH | F. |

In the centuries that followed, the Etruscans consistently used the letters mentioned, so that deciphering the Etruscan inscriptions was not a problem. As in Greek, the characters were subject to regional and temporal changes. Overall, an archaic script from the 7th to 5th centuries can be compared to a more recent script from the 4th to 1st century BC. BC, in which some characters were no longer used, including the X for a Sch sound. In addition, internal vowels have not been used in writing and language with the emphasis on the first syllable, e.g. B. Menrva instead of Menerva . Accordingly, linguistics also differentiates between Old and Young Etruscan.

When transcribing , which is inconsistent in upper or lower case letters, the Greek letters θ or ϑ, φ and werden are occasionally used instead of the double consonants th, ph and ch.

Inscriptions

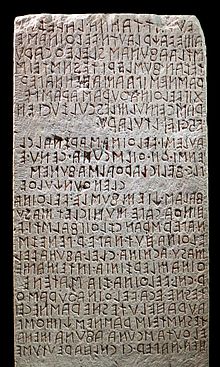

Most of the approximately 13,000 texts recorded are urn and sarcophagus inscriptions, which often contain the name of the deceased, the names of the parents and, in the case of women, the name of the spouse, biographical information on offices and the age of the deceased. There are also owner inscriptions on grave supplements and building inscriptions from graves. Consecration or dedication inscriptions on temple offerings are also relatively numerous.

The inscriptions were mostly with mirror-inverted letters to the left, i.e. H. Written from right to left. There are some exceptions to this, including the engraving on the Kalchas mirror , some grave inscriptions in the Crocifisso del Tufo necropolis near Orvieto and very early texts from the 7th century BC. A few, very old texts are also written as a bustrophedon , i. H. alternately left and right. From the 3rd century BC There are inscriptions that were apparently made under the influence of the Romans.

In the earliest inscriptions, the individual words were not delimited from one another. So one letter followed another ( scriptio continua ). Only later was the inscriptions broken down into individual words. Dots, colons or three dots on top of each other were often used to separate the words in the text. Sometimes you separated individual words according to syllables. This syllable separation can be found in texts from the middle of the 6th century BC. Until the end of the 5th century, when the division of texts into individual words had become common.

Written monuments

In addition to the writing tablet by Marsiliana d'Albegna , around 70 objects with model alphabets have been preserved from the early days . The best known of them are:

- Alabastron from the Tomba Regolini-Galassi in Cerveteri

- Bucchero amphora from Formello

- Viterbo Bucchero Chicken

- Bucchero vessel from the Sorbo necropolis near Cerveteri

Since all four artifacts from the 7th century BC The alphabets are written clockwise. The last object has the peculiarity that in addition to the letters of the alphabet, almost all consonants are shown in sequence in connection with the vowels I, A, U and E ( syllabars ). This syllable spelling was probably used to practice the characters.

The most important Etruscan written monuments that contain a large number of words include:

- Agramer mummy bandage ( Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis ) - ritual text with about 1400 words

- Clay tablet from Capua ( Tabula or Tegula Capuana ) - ritual text as a bustrophedon with 62 lines and about 300 words

- Table of Cortona ( Tabula Cortonensis ) - contract text with a length of 32 lines and about 200 words

- Cippus Perusinus - travertine block with 46 lines and about 125 words from near Perugia

- Gold sheets from Pyrgi - parallel texts in Etruscan and Punic script

- Pulena scroll - funerary inscription of Laris Pulena with nine lines of text on a sarcophagus scroll

- Bronze liver from Piacenza - model of a sheep's liver with 40 inscriptions

- Magliano lead plate - 70-word sacrifice rule

- Santa Marinella lead strips - Two fragments of a sacrificial vow

- Architectural inscription of the grave of San Manno near Perugia - consecration inscription comprising 30 words

- Aryballos Poupé - Clockwise dedication inscription on a Bucchero bottle

- Tuscania dice - two dice with the number words from 1 to 6

Nothing has survived from a more extensive literature of the Etruscans. From the early 1st century AD, inscriptions with Etruscan characters have not survived.

All existing ancient Etruscan documents are systematically collected in the Corpus Inscriptionum Etruscarum .

Aftermath

Middle of the 7th century BC The Romans took over the writing system and the letters of the Etruscans. In particular, they used the three different characters C, K and Q for a K sound. The Z was also initially adopted in the Roman alphabet, although the affricate TS did not appear in the Latin language. Later, the Z in the alphabet was replaced by the newly formed letter G, which was derived from the C, and finally the Z was placed at the end of the alphabet. The letters Θ, Φ and Ψ were omitted by the Romans because the corresponding aspirated sounds did not appear in their language.

The Etruscan alphabet spread over the northern and central part of the Italian peninsula. With the formation of the Oscar script probably in the 6th century BC One assumes a fundamental influence of the Etruscan. The characters of the Umbrian , Faliscan and Venetian languages can also be traced back to Etruscan alphabets.

Regarding the origin of the Germanic runic writing , u. a. represent an Italo-Etruscan thesis , according to which the origin of these characters is to be ascribed to a large extent to the spread of North Etruscan alphabets. The runic script probably developed as early as the 3rd century BC. From Venetian characters of Etruscan origin, which had reached the Alps on trade routes. No rune inscriptions have been found from this early period. Probably the first written documents were made on organic material such as wood.

literature

- Giuliano Bonfante , Larissa Bonfante : The Etruscan Language. An Introduction. 2nd Edition. Manchester University Press, Manchester / New York 2002, ISBN 0719055407 .

- Robert Hess, Elfriede Paschinger: Etruscan Italy. 3. Edition. DuMont, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3770106377 .

- Friedhelm Prayon : The Etruscans. History, religion, art. 5th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 9783406598128 .

- Steven Roger Fischer: History of Writing . Reaction Books, London 2001, ISBN 9781861891679 .

- Herbert Alexander Stützer : The Etruscans and their world. DuMont, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3770131282 .

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Herbert Alexander Stützer: The Etruscans and their world. P. 11.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 14.

- ^ Friedhelm Prayon: The Etruscans. History, religion, art. P. 38.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P.56.

- ↑ Steven Roger Fischer: History of Writing. P. 138.

- ↑ Herbert Alexander Stützer: The Etruscans and their world , pp. 11-14.

- ^ Hess / Paschinger: The Etruscan Italy. P. 17.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. Pp. 54 and 76.

- ^ Friedhelm Prayon: The Etruscans. History, religion, art. P. 38.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 78.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 78.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 52 and 78.

- ↑ Steven Roger Fischer: History of Writing. P. 140.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 78.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 77.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 14.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 54.

- ↑ Steven Roger Fischer: History of Writing. P. 140.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. Pp. 75-77.

- ↑ Steven Roger Fischer: History of Writing. P. 140.

- ^ Hess / Paschinger: The Etruscan Italy. P. 18.

- ^ Herbert Alexander Stützer: The Etruscans and their world. P. 14.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 78.

- ↑ Steven Roger Fischer: History of Writing. P. 140.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 81.

- ^ Friedhelm Prayon: The Etruscans. History, religion, art. Pp. 38-40.

- ^ Hess / Paschinger: The Etruscan Italy. Pp. 19-20.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 55.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P.56.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 55.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 133.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 14.

- ↑ Steven Roger Fischer: History of Writing. Pp. 141-142.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 117.

- ^ Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. Pp. 119-120.