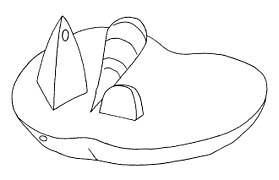

Bronze liver from Piacenza

The bronze liver of Piacenza is a model of sheep liver from the late 2nd or early 1st century BC. And probably served as a teaching model for Etruscan priests ( haruspices ) at the liver exhibition . In ancient times, the liver was the main part of the intestines and, alongside the heart, the central organ of life. The will of the gods shaping the macrocosm was reflected in the microcosm of the liver, according to ancient beliefs. The priests' task was to know the regions of the gods on the liver and to correctly interpret conspicuous signs. With the help of the bronze liver, the Etruscan lightning gods of the 16 regions of the sky could be largely identified.

Discovery story

According to a report by A. Gaetano Tononi in Emilia-Romagna, the bronze liver from Piacenza was dug up in a field near Settima in the municipality of Gossolengo not far from Piacenza by a farmer while plowing. Ancient objects had previously been found in the field. The farmer put his find under a tree and continued his work. In the evening he fetched the find, cleaned it and took it home.

He later brought the find to Pastor Luigi Fulcini in the hope of receiving money for it. Count Giuseppe Gazzola, a large landowner in the area, heard about the lost property and asked the priest to send it to him to show it to Count Francesco Caracciolo, with whom he was staying. Caracciolo decided to purchase the find and let the farmer carry out additional excavations at the site for a few days, but this was unsuccessful. In the end he paid the farmer about 60 lire. Caracciolo had the bronze liver drawn, photographed and cast in plaster of paris.

In the spring of 1878, Gaetano Tononi showed a photograph to his friend Giovanni Mariotti, director of the Royal Museum in Parma . This informed Capitano Vittorio Poggi (1833-1914), a scientifically trained officer who had become known through the publication of Etruscan inscriptions and who had experience in assessing ancient finds. Poggi agreed to publish on the bronze liver, which he recognized as Etruscan. Count Caracciolo then sent him the original to Parma for a few days to study more closely.

In the summer of 1878 Poggi's treatise Di un bronzo Piacentino con leggende Etrusche ( About a bronze from Piacenza with an Etruscan legend ) appeared with 26 pages and three illustrations in the book series of the local history association of Emilia and later also in a separate print. In his essay, Poggi provided a short find report with a description, interpreted the writing correctly and went through the incised names of gods in 47 numbers, which he had mostly correctly read and interpreted. The conclusion is a brief discussion of the possible meanings of the find. He himself thought the object was an amulet and explained some general concerns about its authenticity.

Since 1894, the bronze liver has been in the possession of the Museo Civico of Piacenza, which is located in the Palazzo Farnese. The bronze liver is currently on display in the basement of a small tower of the Cittadella Viscontea.

description

The bronze liver is 12.6 cm long, 7.6 cm wide and 6.0 cm high. The Etruscan characters are 4 to 6 mm high. The weight of the bronze liver is 635 g.

The top is flat with the exception of three bumps. At the top left is a three-sided pyramid , 3.9 cm high and regularly shaped, with a curved equilateral triangle as the base. The edges of the pyramid are not straight, but convexly curved. On the left side of the pyramid there is a round-oval hole about 1 cm below the top. The second elevation corresponds to a quarter of an ellipsoid , is 1.7 cm high, 2.0 cm long and 1.0 cm thick. The third elevation is a half-cone with a length of 5.6 cm, which lies firmly over its entire length and is spherically rounded at the base . The maximum width is 2.0 cm, the maximum height 1.5 cm.

Lines and letters are deeply carved on the flat top and the half-cone, most of the letters are still legible. The lines and elevations divide the surface into a total of 40 fields in which the names of Etruscan deities are engraved. A wide strip with 16 fields runs around the edge. In the left half, six fields are arranged approximately in a wheel with six spokes. On the right, the fields form an approximately rectangular shape.

The underside is convex. A flat, raised strip leads from the bottom to the top, which widens slightly at both ends and constricts the bottom in two halves. On the side with the pyramid, the maximum thickness is about 2.0 cm, on the other side 1.7 cm. At the top of the strip there is an incised inscription on both sides. The bottom has a clearly visible hole on the upper edge and on the right side.

The upper side of the model corresponds to the division of a sheep's liver into a left and right half of the liver ( lobus sinister / lobus dexter ). There is also the tail lobe ( lobus caudatus ), which is supposed to be embodied by the pyramid. The half-cone represents the gallbladder ( vesica fellea ). The quarter ellipsoid in the middle of the model probably corresponds to the papillary process of sheep's liver ( processus papillaris ). The strip on the back represents a ligamentum teres hepatis ( ligamentum teres hepatis ). The top shows the part of the sheep's liver that is directed towards the intestines, the bottom the part that rests on the animal's back. The holes mentioned are located at places where blood vessels connect to the liver.

The chemist Dioscoride Vitali first investigated the composition of the bronze liver in Parma around 1880 . He found that the find consists mainly of copper with a relatively small admixture of tin . There are also traces of iron in it. This composition is consistent with a bronze - alloy agreement, which was often found in antiquity. The patina corresponded to that of a bronze object that had been buried in the earth for a long time.

The inscriptions

The inscriptions in the fields are almost clearly deciphered and transcribed .

The inscriptions in the individual fields

The table follows the standardized numbering and transcription by Alessandro Morandi .

Tivs (left) and Usils (right), genitive forms of Tiv (moon) and Usil (sun) are carved on the back of the bronze liver . The two halves of the liver are accordingly marked with (part of) the moon and the sun . The liver could thereby be divided into an ominous hostile part ( pars hostilis ) and an auspicious friendly part ( pars familiaris ) with regard to divination . The deities in the 16 peripheral fields correspond to the gods of the 16 heavenly regions from the Etruscan lightning theory , who lived in these regions of the sky and from there threw their lightning bolts.

Some gods are named multiple times. With some inscriptions it is doubtful whether they are god names. Some inscriptions may indicate certain functions of deities, for example in field 14 the deity Cul in the function of Alp or in field 2 Tin in the function of Thvf . The inscription Metlvmth in field 38 does not seem to be a name either , but rather to stand for a group of people or rooms. In field 17, instead of Tur, the reading Pul is given, meaning heaven, as opposed to Metlvmth of field 38, which is then interpreted as earth . There should be a total of 24 different god names.

The gods of the bronze liver

The table follows the designations and attributions by L. Bouke van der Meer.

| No. | inscription | Deity | field |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cath | Catha ( Eos ) - sun deity | 8/23 |

| 2 | Celsth | Cel ( Gaia ) - earth goddess? | 13 |

| 3 | Cilen | Cilens - goddess of fate | 1/16/36 |

| 4th | Cvl Alp | Culsu / Culsans ( Janus ) - god of gates | 14th |

| 5 | Fufluns | Fufluns ( Dionysus ) - god of wine | 9/24 |

| 6th | Herc | Hercle ( Heracles ) | 29 |

| 7th | Lar | Laran ( Mars ) - god of war | 26th |

| 8th | Lasl | Lasa - companion of the Turan | 19th |

| 9 | Letha | Lethan - underworld god? | 11/18/27/32/37 |

| 10 | Lvsl | Lusa - goddess of fertility? | 6/33 |

| 11 | Mae | Mae -? | 4th |

| 12 | Mar | Maris - son of Laran and Turan? | 26/30/39 |

| 13 | Neth | Nethuns ( Neptune ) - god of the sea | 7/22/28 |

| 14th | Satres | Satre ( Saturn ) - god of fertility | 35 |

| 15th | Selva | Selvans ( Silvanus ) - nature deity | 10/31 |

| 16 | Tecvm | Tecum -? | 5 |

| 17th | Tin | Tinia ( Jupiter ) - main god | 1/2/3/20/22 |

| 18th | Tlusc | Tluscu - earth god? | 12/33/40 |

| 19th | Door | Turan ( Venus ) - goddess of fertility | 17th |

| 20th | Tvnth | Tunth ( Demeter ) - goddess of fertility? | 25th |

| 21st | University | Uni ( Juno ) - goddess of fertility | 4th |

| 22nd | Vetisl | Vetis ( Veiovis ) - underworld god | 15th |

| 23 | Velch | Velchans - god of fertility? | 34 |

| 24 | Thvfthas | Thufultha - underworld goddess? | 2/20/21 |

In spite of all efforts, some deities have not yet been clearly identified, as reading and interpretation are made more difficult by the fact that abbreviations are often used in the inscriptions and possibly different spellings are used for the same deity. In addition, some god names appear exclusively on the bronze liver. The endings -l or -s indicate feminine or masculine genitive. About half of the gods mentioned are of genuinely Etruscan origin, the other half was adapted from the Roman or Greek world of gods. The Greek hero Heracles was worshiped as a god by the Etruscans and later by the Greeks and Romans . It is unclear why important deities such as the underworld rulers Aita ( Hades ) and Phersipnai ( Persephone ) as well as Apulu ( Apollon ) and Menrva ( Athene ), who were of great importance in cult and the visual arts, are missing on the bronze liver of Piacenza .

Ancient sources

The knowledge about the intestinal inspection ( haruspicinum ) and the lightning theory were handed down by the Etruscans in the books of the Etrusca disciplina , as the Romans called them. The Disciplina included the libri haruspicini , the libri fulgurales and the libri rituales . None of these works have survived, although Roman writers took over some of the Latin translations of these books. Since numerous Roman works have also been lost, the remaining literature on the Etruscans is fragmentary. Details of the liver and blitz show have not survived.

The few surviving reports about the liver inspection relate to the "head" of the liver, the tail lobe, which is depicted as a pyramid on the bronze liver and in ancient sources such as Livy (59 BC – 17 AD) as caput iocineris referred to as. A missing or deformed head was considered disastrous at the liver inspection. A crack in the tail lobe was considered an unfavorable sign, except in the case of fear or restlessness. Then the offending nuisance could come to an end. A greatly enlarged liver, on the other hand, was a good omen, as was a double head. From Cicero (106–43 BC) it is narrated that the liver is divided into an ominous hostile part ( pars hostilis ) and an auspicious, friendly part ( pars familiaris ).

According to Pliny (23 / 24–79 AD) the Etruscan gods of lightning lived in 16 regions of the sky, each with four sectors in the four quadrants of the cardinal points. Lightning from the east was considered cheap, lightning from the west was considered ominous. Tinia , the main god of the Etruscans and comparable to the Roman Jupiter , could throw lightning from three different regions. The lightning bolts that he hurled after consulting the council of the twelve gods ( dei consentes ) did not bode well on the whole. The lightning bolts, about which the gods of fate, the supreme and veiled gods ( dei superiores et involuti ) were asked, were considered particularly ominous.

According to the Roman view, however, the first three regions of the sky from north to northeast were reserved for the lightning bolts of Jupiter. Jupiter could also throw its lightning bolts from all regions of the sky. Martianus Capella , a Roman encyclopaedist of the 5th or early 6th century, assigned Roman god names to the 16 heavenly regions in his work De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii . Jupiter can be found in all regions of the sky.

Research history

Wilhelm Deecke (1831-1897) dealt in detail with the bronze liver in 1880 in his Etruscan research in the fourth volume under the title Das Templum von Piacenza . He largely correctly deciphered the Etruscan inscriptions in the 40 fields and was able to demonstrate that the 16 surrounding fields on the edge of the bronze liver represent the 16 heavenly regions of the Etruscan lightning theory. A systematic comparison of the gods in the 16 surrounding fields of the bronze liver with the gods of the heavenly regions by Martianus Capella showed a relatively high degree of correspondence with ancient sources, so that the books of the Etrusca Disciplina could be concluded as a common source for both classifications.

Deecke assumed that the first two regions of the Tinia are to be assigned to the western half, and ended his census with these zones in the north. Then he compared the Martian's regions with his census and came to no convincing agreement. Deecke suspected that the bronze liver was a miniature representation of a temple , that is, a sacred area for divination. This approach is not pursued further in modern research. Today it is assumed that the sheep liver itself is the holy place, the templum .

Carl Olof Thulin (1871–1921) relocated the first two regions of Tinia in his work The Gods of Martianus Capella and the Bronze Liver of Piacenza, also in the western half, since lightning from these two regions heralded a misfortune according to ancient sources, and suspected one Shifting of several zones to the east in Roman times, including that of the supreme lightning god. Undoing this shift resulted in greater similarities. Thulin's reading of the names of the gods and the assignment of corresponding Roman gods are still valid today.

The lightning gods of the bronze liver

The table follows the designations and attributions of Friedhelm Prayon.

| region | inscription | Etruscan deity | Deity and region according to Martianus Capella |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tins / thne | Tinia ( Jupiter ) - supreme lightning god | Jupiter (III) |

| 2 | Uni / Mae | Uni ( Juno ) - goddess of fertility | Juno (II) |

| 3 | Tec / vm | Tecum = Menrva ( Minerva ) - daughter of Tinia and Uni | Minerva (III) |

| 4th | Lvsl | Lusa -? | ? |

| 5 | Neth | Nethuns ( Neptune ) - god of the sea | ? |

| 6th | Cath | Cavtha ( Eos ) - sun deity | Solis filia (VI) |

| 7th | Fuflu / ns | Fufluns ( Dionysus ) - god of wine | Liber (VII) |

| 8th | Selva | Selvans ( Silvanus ) - nature deity | Veris fructus (VIII) |

| 9 | Lethn | Lethans -? | ? |

| 10 | Tluscv | Tluscu -? | ? |

| 11 | Cels | Cel - earth goddess | ? |

| 12 | Cvl / Alp | Culsu / Culsans ( Janus ) - god of gates | ? |

| 13 | Vetisl | Vetis ( Veiovis ) - god of the underworld | Veiovis (XV) |

| 14th | Cilensl | Cilens - goddess of fate | Nocturnus (XVI) |

| 15th | Tin / Cil / en | Tinia with the goddess of fate Cilens | Jupiter (I) |

| 16 | Tin / Thvf | Tinia with a punitive function | Jupiter with Di Consentes (II) |

Some of the modern research follows the Thulin approach, but no longer looks for comprehensive agreement in the regions. Another part in Etruscology assigns the three heavenly regions of Tinia to the eastern half according to Roman sources and thus also achieves a certain correspondence with the regions of Martianus Capella.

In 1982 Adriano Maggiani provided a fundamental overview of the problems of reading and interpreting the names of gods carved into the bronze liver. L. Bouke van der Meer made a significant contribution to the interpretation of the bronze liver of Piacenza in 1987 in his work The Bronze Liver of Piacenza. Analysis of a polytheistic structure , which takes into account almost all epigraphic, literary and archaeological sources.

literature

- Wilhelm Deecke : Etruscan research. Booklet 4: The Templum of Piacenza. Albert Heitz, Stuttgart 1880. ( online )

- Carl Olof Thulin : The gods of Martianus Capella and the bronze liver of Piacenza . Töpelmann, Giessen 1906. ( online )

- Carl Olof Thulin: The Etruscan Discipline: I. The Blitzlehre . Zachrissons, Göteborg 1906. ( online )

- L. Bouke van der Meer : The Bronze Liver of Piacenza. Analysis of a polytheistic structure . Gieben, Amsterdam 1987, ISBN 9070265419 .

- Massimo Pallottino : Etruscology. Etruscan history and culture. Birkhäuser, Basel et al. 1988, ISBN 3764318740 .

- Herbert Alexander Stützer : The Etruscans and their world . Revised and expanded edition. DuMont, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3770131282 .

- Susanne William Rasmussen: Public Portents in Republican Rome . L'Erma di Bretschneider, Rome 2003, ISBN 8882652408 .

- Nancy Thomson de Grummond : Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia PA 2006, ISBN 9781931707862 .

- Friedhelm Prayon : The Etruscans. Concepts of the afterlife and ancestral cult. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3805336195 .

- Friedhelm Prayon: The Etruscans. History, religion, art . 5th, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 9783406598128 .

See also

Web links

- Panorama Musei Piacenza: Il fegato etrusco di Piacenza (Italian)

- Musei di Palazzo Farnese Piacenza: Il fegato etrusco (Italian)

- Massimo Pittau : Il fegato di Piacenza (Italian)

Individual evidence

- ^ Massimo Pallottino: Etruscology: History and culture of the Etruscans. P. 504.

- ^ Herbert Alexander Stützer: The Etruscans and their world. P. 157.

- ^ Atti e Memorie delle RR. Deputazioni di Storia Patria dell'Emilia . Nuova Series Vol. IV, Modena 1878, pp. 1-26.

- ^ Wilhelm Deecke: Etruscan research. Fourth book: The Templum of Piacenza. Pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Alessandro Morandi: Nuove osservazioni sul fegato bronzeo di Piacenza . In: Mélanges de l'Ecole française de Rome. Antiquité , Vol. 100, No. 1, 1988, p. 283.

- ^ Susanne William Rasmussen: Public Portents in Republican Rome. P. 126.

- ^ Wilhelm Deecke: Etruscan research. Fourth book: The Templum of Piacenza. Pp. 5-7.

- ^ Susanne William Rasmussen: Public Portents in Republican Rome. Pp. 126-127.

- ^ Wilhelm Deecke: Etruscan research. Fourth book: The Templum of Piacenza. Pp. 5–7 and p. 2.

- ↑ Alessandro Morandi: Nuove osservazioni sul fegato bronzeo di Piacenza . In: Mélanges de l'Ecole française de Rome. Antiquité , Vol. 100, No. 1, 1988, p. 287.

- ^ L. Bouke van der Meer: The Bronze Liver of Piacenza. Analysis of a polytheistic structure. P. 147.

- ↑ Friedhelm Prayon: The Etruscans: Concepts of the afterlife and ancestor cult. Pp. 76-77.

- ^ L. Bouke van der Meer: The Bronze Liver of Piacenza. Analysis of a polytheistic structure. P. 95 and p. 21.

- ^ L. Bouke van der Meer: The Bronze Liver of Piacenza. Analysis of a polytheistic structure. P. 32 ff.

- ^ Massimo Pallottino: Etruscology: History and culture of the Etruscans. P. 511.

- ↑ Cicero, De divinatione 1, 72.

- ^ Herbert Alexander Stützer: The Etruscans and their world. P. 155 ff.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita 41, 14.

- ↑ Cicero, De divinatione 2, 32.

- ^ Pliny, Naturalis historia 11, 190.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita 27, 26.

- ↑ Cicero, De divinatione 2, 28.

- ↑ Pliny, Naturalis historia 2, 143.

- ↑ Seneca, Naturales quaestiones 2, 41.

- ^ Acron , Commentarii in Q. Horatium Flaccum 1, 12, 19.

- ^ Servius , Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid 8, 427.

- ↑ Martianus Capella, De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii 1, 41-61.

- ^ Wilhelm Deecke: Etruscan research. Fourth book: The Templum of Piacenza. Pp. 24-73.

- ^ Wilhelm Deecke: Etruscan research. Fourth book: The Templum of Piacenza. P. 11.

- ↑ Carl Olof Thulin: The gods of Martianus Capella and the bronze liver of Piacenza. Pp. 32-33.

- ^ Friedhelm Prayon: The Etruscans. History, religion, art. P. 68–76 and The Etruscans: Concepts of the afterlife and ancestor cult. Pp. 76-78.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend. Pp. 48-51.

- ^ Adriano Maggiani: Qualche osservazione sul fegato di Piacenza . In: Studi Etruschi 50, 1982 (1984), pp. 53-88.