John Dee

John Dee (born July 13, 1527 in London , † 1608 or 1609 in Mortlake - Surrey ) was an English mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer and mystic . Under Queen Mary I , Dee was charged with black magic and sorcery. After Mary's death he was appointed court astrologer and royal advisor by the heir to the throne, Elisabeth I. In 1564 he taught Elizabeth I astrology and advised her leading ministers Francis Walsingham and William Cecil .

In his book Monas Hieroglyphica , published in 1564 , he used mathematics, Kabbalah and alchemy to trace creation back to a unity of point, line and circle.

Dee devoted himself to Judeo-Christian magic, astrology and hermetic philosophy, and from 1582 to 1587 the medium Edward Kelley assisted him in making contact with angels . The Enochian language emerged from this collaboration .

As a famous scholar, he devoted himself to technical-scientific, philosophical-Neoplatonic and esoteric studies and gave lectures at the University of Paris at an early age . He was a leading expert in navigation and trained many of the English who were to make voyages of discovery across the Atlantic. In one of several treatises that Dee wrote in the 1580s to stimulate British exploration expeditions to find the Northwest Passage , he coined the term " British Empire ".

As a supporter of the Neo-Platonism of the Renaissance (main exponent Marsilio Ficino ), mathematical research and investigations into hermetic magic and divination were not incompatible for Dee, but he viewed these activities as different aspects of a consistent worldview with the same task: the search for a transcendent understanding of the divine ideas that are behind the visible world.

According to the scholars Frances Yates and Peter French , Dee owned the largest library in England and one of the largest in Europe during his lifetime.

life and work

Early life

Dee was born in 1527 as the son of the wealthy Rowland Dee, who came from the old nobility, in Tower Ward ( City of London ). The Welsh family name Dee is said to have been derived from Welsh du ('black'). Dee attended Chelmsford Chantry School and from 1542 St John's College in Cambridge . In 1545 he received the Bachelor of Arts . In May 1547 he traveled to the Netherlands to study with the mathematician and astronomer Gemma Frisius and his pupil, the cartographer Gerhard Mercator . Equipped with Mercator's astronomical instruments, which he acquired for Trinity College , Dee returned to Cambridge a few months later. The acquisition of such devices and cards was of great importance to England's role as a rising colonial power in competition with Portugal and Spain.

In 1548 Dee was made a Master of Arts . He left Cambridge again, stayed in France and Leuven . During this time he also studied alchemy and the then scientific branch magia naturalis and acquired an excellent scientific reputation, which gave him access to the highest circles. He maintained contacts with the Duke of Mantua , with Johann Capito , the personal physician of the Danish king, with Luis de la Cerda , the later Duke of Medinaceli , with Sir William Pickering and the court mathematician Mathias Hacus . In 1550 Dee traveled to Paris, where he had contacts with Adrianus Turnebus , Petrus Ramus , Amarus Ranconet , Jean François Fernel and Pedro Nunes . In 1552 he met Gerolamo Cardano in London. During their acquaintance, they worked on a perpetual motion machine and examined a gemstone that was said to have magical properties. Dee lectured on Euclid in Paris .

In 1554 Dee was offered a chair in mathematics at Oxford , which he refused because, in his view, the English universities were too focused on rhetoric and grammar - these two subjects, together with logic, formed the academic trivium - while philosophy and science, that is, the more advanced quadrivium , which included arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy, would be neglected. Dee presented Queen Maria I with a visionary plan for the preservation of ancient books, manuscripts and records and proposed the establishment of a national library in 1556 , but his plan found no support. Instead, he built a private library in his house in Mortlake by constantly buying books from England and the European continent. His library with around 4,000 volumes became the largest collection in England of its time and attracted many scholars. In 1555, like his father, Dee became a member of the Worshipful Company of Mercers through the system of inheritance ( patrimony ) of the guild .

In the same year, 1555, under the reign of Mary I, he was arrested and charged with practicing black magic and sorcery against the queen. The charge of treason against Maria was later added to the indictment. Dee appeared before the Star Chamber and defended himself, but was assigned to the Catholic Bishop Bonner for religious appraisal. Dee was released after a brief detention. Dee later became a close friend of Bonner's.

When Elizabeth I ascended the throne in 1558, she appointed him her closest advisor on astrology and science. However, he never got a job that ensured him financial independence. He was also entrusted with the choice of Elisabeth's coronation date. In the 1550s to 1570s he served as an advisor on England's voyages of discovery, offered technical assistance with navigation and ideological support in founding the " British Empire ". In 1577 Dee published General and Rare Memorials pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation , a work that sets out his vision of a maritime empire and alleged English territorial claims to the New World .

Dee was acquainted with Humphrey Gilbert and was close to Sir Philip Sidney and his circle. A friend and pupil was the early English Copernican Thomas Digges . It is also known that Queen Elizabeth I visited his house in Mortlake several times, for example in 1574, where he showed her his magic crystal. In 1577 he gave her his opinion on the new comet in Windsor and in 1578 he advised her on questions of her health and is said to have traveled to Germany for this reason. In 1580 the queen visited him again.

In 1564 Dee published the hermetic work Monas Hieroglyphica ('The Hieroglyphic Monad '), the exhaustive Kabbalistic interpretation of a glyph of unique construction, with which the mystical unity of all creation was to be expressed. This work was highly valued by many of Dee's contemporaries. He is also said to have been in Antwerp in preparation for their printing.

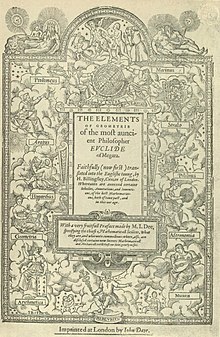

In 1570 he published a Mathematical Preface ('Mathematical Introduction') to Henry Billingsley's English translation of Euclid's Elements , in which he emphasized the central importance of mathematics and its influence on the other arts and sciences. Although originally intended for the uneducated reader, it proved to be Dee's most influential work and was widely reprinted.

Next life

In the early 1580s, Dee became increasingly discontented as he made little progress in learning the secrets of nature, his plans for expeditions in North America were not moving forward, and his influence at court waned. He began to turn to the supernatural in an effort to gain wisdom. He sought contact with angels with the help of a "scryer" or crystal seer, which acted as a medium between Dee and the angels.

As evidenced by his book collection (the catalog of which is known), Dee had more than a passing interest in angels. He was very concerned with angelology and especially with communication with angels; so he collected all the written conversations between humans and angels. He studied the commonalities of the Engels Conversations with various texts, among others by Ficino, Agrippa von Nettesheim and Johannes Trithemius as well as the widespread biblical apocrypha and pseudepigraphy . Dee was familiar with one of the greatest mathematicians of his time, Gerolamo Cardano , who often spoke of his guardian angel . Agrippa encouraged his readers to seek “a voice from above, a voice that teaches from above”. Agrippa's teacher, Johannes Trithemius, discussed in De septem secundeis a distance communication based on the seven classical planets and their angels “according to the tradition of the ancient sages”. Dee also owned at least 16 works by Robert Grosseteste , with whom he shared a synergistic interest in angels, but also optics , mathematics and astronomy. All of these mathematicians, cryptographers, and philosophers, who claim to have had revelations through angels, agreed that divine messengers, companions on journeys of revelation, and angels of the Apocalypse were common and trustworthy sources of information for the ancient patriarchs .

His own first attempts in this direction did not satisfy him, but in 1582 he met the medium Edward Kelley , a man of dubious past and character, who, however, impressed him with his alleged skills to a great extent. Dee took Kelley into his service and began to devote himself entirely to psychic goals. These "angelic conversations" or "spiritual conferences" were imbued with intense Christian piety and continuous periods of purification , prayer and fasting. Dee was completely convinced that they could help humanity with the results. Several books are said to have been dictated to Dee by the angels, who allegedly revealed the Enochian language to him and opened up a new magical system. He kept a diary of the seances with Kelley and the subsequent trips with him that has survived. Meric Casaubon published the recorded conversations during the seances in 1659.

In 1583 Dee met the Polish nobleman Albrecht Laski (1536-1605), who invited the English to accompany him on his return journey to Poland. After asking the angels some questions about Kelley, Dee was ready to go. Dee, Kelley and their families left England in September 1583, first via the Netherlands and Lübeck to Stettin to the Laski estate and then to Krakow . Laski's resources, however, were exhausted and he suggested that Dee and Kelley should go to Emperor Rudolf II , where Dee, who enjoyed a European reputation, was also welcomed. The Kaiser, however, was suspicious of Kelley. After several months in Prague, where they were still living at Laski's expense, they had to leave the city at the complaint of the papal ambassadors Malaspina and Sega, who wanted to hand them over to the Inquisition as heretics and sorcerers. They went to Erfurt and Kassel , where they were not well received, and then back to Krakow, where they were initially well received by King Stephen of Poland and predicted good chances for him to succeed Rudolph II as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Due to ever new demands for money, he soon got tired of them and they went back to Bohemia, where they found a new sponsor in Wilhelm von Rosenberg at his castle Třeboň in Wittingau .

Tension had grown between Dee and Kelley. In addition, Kelley, who was more unscrupulous than Dee, who was naive in his belief in spiritualism, was also self-employed as an alchemist and alleged gold maker at Rosenberg and beyond - Queen Elizabeth I and Rudolph II were also interested in him - and possibly Dee wanted to get rid of. The break occurred after Kelley, after he had initially worried Dee with proposed separation intentions, informed him during a seance in Wittingau in 1587 that the angel Uriel had ordered the two men to swap wives. According to the diary, Dee and his wife seem to have reluctantly consented at first, but shortly afterwards they parted ways and Dee went back to England.

Private life

Dee was married three times and had eight children. His eldest son was Arthur Dee , about whom Dee wrote a letter to his headmaster at Westminster School , detailing his parents' concerns about boarding school students; Arthur was also an alchemist and Hermetic writer. John Aubrey described Dee as follows: “He was tall and slim. He wore a cape similar to an artist's cape, with hanging sleeves and a slit [...] a very beautiful, lively complexion [...] a long beard as white as milk. A very handsome man. "

The last few years

In 1589 he returned to England, where he found his library ruined; many of his books and instruments had been stolen during his absence. He asked for support from Elisabeth, who finally appointed him rector of Christ's College in Manchester (now Manchester Grammar School ) in 1592 . However, he was now widely disdained as a black magician and therefore had little influence on his subordinates and attempts were made to depose him. In the meantime Elisabeth had died and Jacob I followed her to the throne, who was known for his witch hunts and from whom Dee could not expect any help. When Dee nevertheless turned to him for help in 1604 with regard to the charges brought against him, the latter promptly rejected him. He spent his last years in poverty and died in Mortlake in late 1608 or early 1609. Both the death register and Dee's tombstone have been lost.

The UK Antarctic Place-Names Committee named the Dee Piedmont Glacier in Antarctica after him in his honor on August 31, 1962 .

Achievements

In thinking

Dee was an intensely devout Christian, but his religiosity was profoundly influenced by the Hermetic and Platonic - Pythagorean doctrines prevalent during the Renaissance . He believed that the basis of all things and the key to wisdom are numbers; God's creation is an act of counting.

From hermetics he derived his belief in the human potential to be a god, and he believed that the divine powers could be controlled with mathematics. He saw his kabbalistic angel magic (which is highly numerological ) and his work on practical mathematics (such as navigation) as glorified and earthly ends of the same spectrum, and not as contradicting. His greatest goal was to contribute to a unified world religion by bridging the rift between the Catholic and Protestant churches and regaining the pure theology of antiquity.

Reputation and Importance

His own library in Mortlake was the largest in the country and one of the finest in Europe, perhaps only surpassed by that of de Thous . In addition to his services as astrological, scientific and geographical advisor to Elizabeth I and her court, he was also an early advocate for the British colonization of America and a visionary of a British Empire that spanned the North Atlantic .

Dee promoted the science of navigation and cartography. He studied with Gerhard Mercator and owned an important collection of maps , globes and astronomical instruments. He developed both new instruments and special navigation techniques for use in polar regions . Dee served as a consultant for England's voyages of discovery and personally selected "pilots" (navigators) to train them in navigation. He coined the term embadometry .

He believed that mathematics (which he understood as mystical) was central to the advancement of human learning. The centrality of mathematics in his vision makes him seem more capable of connecting with modernity in this area than the scholar Francis Bacon , although Dee's understanding of mathematics deviated radically from today's view.

His practical achievement, which probably had the longest lasting effect, was the advancement of mathematics outside of universities. His Mathematical Preface to Euclid was intended to promote the study and application of mathematics among people without a university education, and was very popular and influential among the "mecanicians", the new and emerging class of technical masters and craftsmen. Dee's introduction included demonstrations of mathematical principles that readers could understand for themselves.

calendar

Dee was a friend of Tycho Brahe and was familiar with the work of Nicolaus Copernicus . Many of his astronomical calculations are based on the Copernican worldview , but he never publicly endorsed the heliocentric theory. While Dee applied this knowledge to the problem of calendar reform , his recommendations were discarded for political reasons.

Voynich manuscript

It is sometimes mentioned in connection with the Voynich manuscript . Wilfrid Michael Voynich , who bought the manuscript in 1912, has indicated that the manuscript may have been in Dee's possession and he sold it to Rudolf II . However, Dee had far fewer contacts with Rudolf II than previously assumed, and Dee's diaries do not reveal any such sale. However, it is known that Dee owned another encrypted book, the Book of Soyga .

Artifacts

The British Museum houses several items that belonged to John Dee and are associated with his so-called Angel Conversations:

- Dees Spiegel, an Aztec cult object made of highly polished obsidian ( volcanic glass ), in the shape of a hand mirror; 18.4 cm in diameter, and brought to Europe in the late 1520s. Horace Walpole bought the mirror in 1771 .

- A large and well-preserved wax seal, the so-called Sigillum Dei Æmeth , which was used as a base for the “display stone”.

- Two smaller versions of the wax seal mentioned above that supported the legs of his "sacred table".

- A gold amulet in the shape of a disk, engraved with a representation of Kelley's vision of the four watchtowers on June 20, 1584 in Krakow , which Dee considered particularly important. The disc weighs 38.25 grams, has a diameter of 8.8 cm and is made of a red gold alloy (90% Au and 10% Cu ). The pane surface has been refined to a high quality using a chemical process. A hole was punched in the outer, engraved circular band of the disk, which was apparently made for easier handling. However, the disk was only made after Dee's return to his homeland, as evidenced by the mark of a London goldsmith on it.

- A crystal ball , six centimeters in diameter. For many years this piece lay unnoticed in the mineral collection; it may have belonged to Dee, but the origin of this object is less certain than that of the others.

In December 2004, the display stone and the accompanying instructions for its use (written by Nicholas Culpeper , mid-17th century) were stolen from the Science Museum in London. The exhibits could be recovered shortly afterwards.

Reception in literature and music

John Dee is said to have served William Shakespeare as a model for the character of Prospero in The Tempest (1623). More recently, Gustav Meyrink traced the life of John Dee in his esoteric key novel The Angel from the Western Window (1926) in an unusual way. In the Cthulhu myth , inspired by HP Lovecraft's short story The Call of Cthulhu (1928) , Dee is believed to be the one who translated the magic book Necronomicon into English.

Umberto Eco recently assigned a special meaning to the figure of John Dee in his Foucault Pendulum (1988). He is one of the main characters in Michael Scott Rohan 's novel Maxie's Demon (1997). The writer Mary Hoffman Dee served as a model for the natural philosopher William Dethridge in her novel series Stravaganza (2002). In the science fiction novel The Philosophers of the Round World. More of the scholars of Discworld (original title The Science of Discworld II - The Globe , 2002) by Terry Pratchett , Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen, the wizards of the Invisible University get through Dee's library, which is connected to Discworld by the "L-Room" is to our world to protect us from the influence of the elves.

In the series of novels by the Irish writer Michael Scott about the Immortal Alchemyst (original title The Alchemyst: The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel , 2007), John Dee appears as an opponent of Nicolas Flamel and his wife. In the House of the Magician ( At the House of the Magician , 2007) and in a royal order ( By Royal Command , 2010) by Mary Hooper Dee plays one of the main characters. John Dee is also a key figure in German novel series, such as the Lycidas series (from 2004) by Christoph Marzi . In these novels it is assumed that John Dee never died, rather that he appeared later as John Milton and that he is a loyal helper as Lycidas (= Lucifer, Bringer of Light) today . He is also mentioned in the series of youth novels under the title The Kronos Secrets (from 2009) by Marie Rutkoski.

The Iron Maiden song The Alchemist from the album The Final Frontier (2010) sings about the meeting of John Dee and Edward Kelley and the transition between magic and science (2010, EMI-Records).

Fonts

- Monas Hieroglyphica, Antwerp: Gulielmus Silvius 1564, reprint Frankfurt 1592

- also in Theatrum Chemicum 1659

- Translation by JW Hamilton Jones: The hieroglyphic monad, London 1847 and CH Josten A translation of John Dee's "Monas Hieroglyphica" , Ambix, Volume 12, 1964, pp. 83-221

- De Trigono, 1565

- Testamentum Johannis Dee Philosophi Summi ad Johannem Gwynn, transmissum 1568

- Also in Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum 1652

- Mathematical Preface, in Henry Billingsley (translator): The Elements… of Euclide, 1570

- An Account of the Manner in which a Certayn Copper-smith in the Land of Moores, and a Certayn Moore Transmuted Copper to Gold, 1576

- Prefatory Verses to The Compound of Alychymy by George Ripley , set forth by Ralph Rabbards, London 1591

- Wayne Shumaker (Ed.): John Dee on Astronomy. Propaedeumata Aphoristica (1558 and 1568), Latin and English. University of California Press, Berkeley 1978, ISBN 0-520-03376-0

Published posthumously:

- Roger Baconis Epistola de Secretis operibus artis & naturæ, & de nullitate Magiæ. Opera Johannis Dee, è pluribus exemplaribus castigata olim, in Deutsches Theatrum Chemicum , Volume 3, 1732 (commentary on Roger Bacon , first printed in Hamburg)

- A True and Faithful Relation of What Passed for Many Years Between Dr. John Dee… and Some Spirits…. London, 1659 (Meric Casaubon, editor). Reprint, Askin, 1974.

- Edward Fenton (Ed.): The diaries of John Dee, Oxford, Day Books 1998

- JO Halliwell (Ed.): The Private Diary of Dr. John Dee, and the Catalog of His Library of Manuscripts. London: Camden Society , 1842.

His writings on navigation and navigational instruments have not been published and are largely lost.

literature

- Ronny Baier: Dee, John. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 21, Bautz, Nordhausen 2003, ISBN 3-88309-110-3 , Sp. 322-330.

- IRF Calder: John Dee Studied as an English Neo-Platonist. Warburg Institute, London 1952.

- Nicholas H. Clulee: John Dee's Natural Philosophy: Between Science and Religion. Routledge, London 1988, ISBN 0-415-00625-2 .

- Stephen Clucas (Ed.): John Dee: Interdisciplinary Studies in Renaissance Thought. Springer, Dordrecht 2006, ISBN 1-4020-4245-0 .

- T. Cooper: John Dee , in Dictionary of National Biography , Volume 5, 1959/60, pp. 712-729

- Richard Deacon: John Dee: Scientist, Geographer, Astrologer and Secret Agent to Elizabeth I. Frederick Muller, London 1968.

- John Heilbron : Essay on John Dee, in: John Dee on Astronomy: Propaedeumata aphoristica. University of California Press 1978, (editor and translator Wayne Shumaker).

- Charlotte Fell Smith: John Dee: 1527-1608. Constable, London 1909.

- Peter J. French: John Dee: The World of an Elizabethan Magus. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1972, ISBN 0-7102-0385-3 .

- Vladimir Karpenko: John Dee , in: Claus Priesner , Karin Figala : Alchemie. Lexicon of a Hermetic Science, Beck 1998, pp. 106-108

- Martin Kugler: Astronomy in Elizabethan England, 1558 to 1585: John Dee, Thomas Digges, and Giordano Bruno. Université Paul Valéry, Montpellier 1982.

- S. Pumfrey: John Dee, the patronage of natural philosophy in Tudor England , Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A., Volume 43, 2012, pp. 449–459.

- R. Julian Roberts, Dee, John (1527-1609) , Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004

- William Howard Sherman: John Dee: The Politics of Reading and Writing in the English Renaissance. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst 1995, ISBN 1-55849-070-1 .

- Benjamin Woolley: The Queen's Conjurer: The Science and Magic of Dr. John Dee, Advisor to Queen Elizabeth I , Henry Holt 2001

- Frances A. Yates : The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age. Routledge, London 2001, ISBN 0-415-25409-4 (free digitized version ; PDF; 6.0 MB).

- Frances A. Yates: Renaissance Philosophers in Elizabethan England: John Dee and Giordano Bruno. In: Lull & Bruno. Collected Essays Vol. I. London: Routledge Kegan & Paul (1982) ISBN 0-7100-0952-6

- Frances Yates: Theater of the world , Chicago 1969

Web links

- Literature by and about John Dee in the catalog of the German National Library

- The John Dee Society (English)

- "Monas Hieroglyphica" - A webinar about John Dee on the website of the Ritman Library, Amsterdam.

- John Dee, Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology 2001

Individual evidence

- ^ Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century. Vol. 1, Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-044-7 , pp. 276-277.

- ^ Frances A. Yates : Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age. Amsterdam 1991, p. 92.

- ↑ a b The British Museum: Dr John Dee (1527–1608 / 9) ( Memento of the original dated November 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ John Ferguson Bibliotheca Chemica , Volume 1, 1906, p. 202

- ↑ John Ferguson, loc. cit.

- ↑ In detail Joachim Telle: John Dee in Prague. Traces of an Elizabethan Magus in German Literature. In: Peter-André Alt , Volkhard Wels (Hrsg.): Concepts of Hermetism in the literature of the early modern period. (= Berlin Medieval and Early Modern Research. Vol. 8). V&R unipress, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-89971-635-1 , pp. 259-296.

- ^ John Ferguson, Bibliotheca Chemica, Volume 1, 1906, p. 202

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dee, John |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British philosopher, mathematician, astrologer and alchemist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 13, 1527 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | between December 1608 and March 1609 |

| Place of death | Mortlake , Surrey , England |