Subtle matter

The term subtle matter designates a hypothetical form of matter that is said to be finer and more mobile than the gross matter of which the visible bodies are made. The postulated fine matter stands between matter and immaterial and in some philosophical approaches serves to explain an interaction between the two elements or to explain immaterial phenomena in general. Such ideas can be found in some ancient philosophers , especially in Platonism , and, partly in its history of influence, partly independently of it, also in some texts from the cultural area of the three monotheistic religions, such as in Gnosis and Hermetics , as well as in Eastern religions , especially in Hinduism . Similar ideas also existed in the local, traditional religions .

Following up on Hindu and Platonic ideas in their mediation by authors of the Renaissance and the early modern period , the concept of subtle matter was taken up in Spiritism and in parts of the theosophy of the 19th century, subsequently also in various approaches of modern esotericism and in some so-called para- and pseudosciences . There the terms energy , astral , ethereal and subtle are often used more or less synonymously.

In today's natural science , however, such concepts no longer play a role. The existence of a subtle matter could not be proven, likewise no interaction with normal matter can be scientifically observed. "Subtle" is a word that was first coined by anthroposophy in the first half of the 20th century . Rudolf Steiner and Annie Besant initially used the term adjectivally , for example in formulations such as: The etheric body is made up of finer material than our five senses can perceive (...) or "in fine materials" as descriptions for the subtle, they use but not yet as a fixed substantive term.

Concept history

Antiquity

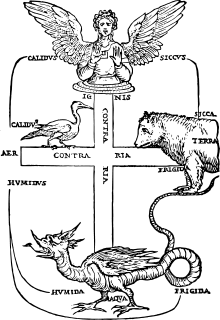

Zenon of Kition in the 3rd century BC BC already knew the quality fine in relation to matter. He defined a subtle fire πνεύμα ( pneuma ) , which is also known as λόγος σπέρματικος (logos spermatikos) , and for him was both spiritual and material. He called this a "passive material principle" which, for example, shapes the mind . Also Eratosthenes and Ptolemy II. Knew subtlety as a principle. Similar to Plato , who explained the immortality of the soul in the Phaedo with the image of the soul wagon, both philosophers justified the persistence of the soul from its subtle nature. According to a combination of Platonic and Aristotelian views already found in early Platonism , both stars and souls consist of an element that does not appear in the other phenomena below the lunar sphere, the ether . This element was described in the Orphic as the world soul , which Proclus takes up again, with Empedocles as divine and "finest air", with the Pythagoreans and Aristotle as the fifth , finest, most flexible element and constituent of the stars, also in Middle Platonism where z. B. Philo of Alexandria describes the ether as the finest material. The Stoa assumes a principle that pervades everything, fiery, subtle and called Logos or Pneuma .

In this tradition, the assumption of a subtle element serves to explain the mediation between matter and immaterial as well as special properties of spirit and soul, especially their immortality, without having to give up proven atomistic natural-philosophical prerequisites. However, this view was not undisputed. In the second century AD, Atticus and Albinus asserted the physicality of the soul and its mortality. A dispute also arose over this between Numenios , who believed in subtle souls, and Alexander von Aphrodisias , who refused to do so. In the 3rd century AD, the Neo-Platonist Porphyrios systematized the older ideas into a consistent theory. He claimed that when the soul descends through the celestial spheres it acquires a pneumatic, irrational part, the anima spiritalis . This part is subtle and darkens and increasingly materializes as it descends further.

Traducianism

The principle of subtle matter reappears in the time of the Church Fathers , especially in the 3rd century AD. Tertullian claimed in his teaching called Traducianism that the soul is composed of subtle soul seeds (semen animae) , whereas the body consists of gross body seeds (semen corporis) . He even explicitly warned against depriving the soul of its physicality because of its subtle nature. According to him, both seeds work together like the clay and the breath of God from which Adam was created. The core of the theory was the doctrine that the human soul is transferred from the souls of the parents - in Tertullian's only the soul of the father (Latin traducere ). This conclusively explains the infection of mankind by original sin .

In church history, however, the opposite doctrine, which could of Lactantius developed creationism prevail. According to him, each individual soul is created immediately and indivisibly. Traducianism has been condemned several times by the Catholic Church and creatianism has been declared a binding doctrine. Since in modern times the assumption of indeterminable, punctual creations from nothing seemed more and more questionable, these older attempts to include the creation of the soul in bodily becoming revived and were taken up by Leibniz , for example . However, the notion of subtle substances disappeared from theology with the end of Traducianism and the soul is widely accepted as indivisible.

Renaissance and early modern times

The ancient idea of a subtle, ethereal element, which is the substrate of stars and souls or envelops them in order to communicate with their bodies, is handed down by natural philosophers and authors of an "occult philosophy" in the Renaissance and early modern times , including Agrippa von Nettesheim .

René Descartes divided the material world into three departments. The earth forms the first and coarsest division, followed by a dark division of finer particles. Finally, the third section consists of the finest “heavenly spheres” . These subtle spheres can diffuse through the spaces between the coarser spheres in the other two compartments . According to Descartes, “all bodies that surround us here can arise from these finest subtle parts .” However, according to Descartes, the material world is to be sharply separated from the immaterial realm of the soul, a subtle explanation of spiritual phenomena is therefore ruled out for him.

But for many Cartesians , not only did subtle matter exist, but also, explained, spiritual phenomena. For Cornelius van Hoogeland , a medicine professor and friend of Descartes, the spirits of life (spiritus animales) consist of a flexible, subtle matter. Friedrich Wilhelm Stosch taught the subtle nature of the human mind. But Descartes opponents like the British Platonist Ralph Cudworth did not reject subtle matter either; for Cudworth, for example, there was a subtle connection between spiritual soul and material body.

In German idealism a more extensive conception of subtle matter u. a. taken up again by Johann Heinrich Jung-Stilling . For him the human being is considered to be threefold into a material body, the absolutely immaterial spirit and a subtle etheric body as a soul vehicle.

Subtle Concepts in Eastern Religions

In contrast to Christianity , where subtle ideas were rejected as heresy early on, they are still important today in the Eastern religions, in Hinduism , Jainism and Buddhism .

Ideas in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism

A central term in the Eastern religions is samsara ( Sanskrit संसार). Samsara describes the everlasting cycle of being, the cycle of becoming and passing away, in the cycle of rebirth . The causes of entanglement in samsara are the kleshas (Sanskrit: क्लेश), the causes of suffering. An important Klesha is the Avidya (Sanskrit अविद्या), which means something like ignorance or ignorance.

In the Paramarthasara , an ancient Advaita-Vedanta script that appeared about three centuries before the writings of Shankara , the Avidya is not only considered a klesha, a cause of suffering, but rather a cause of the world itself. In Samkhya it also becomes Primordial matter called Prakriti (Sanskrit प्रकृति) and consists of three primary forces, the Gunas (Sanskrit गुण). In a process of progressive coarsening, this primary material becomes both the gross material body and the subtle body Sūkṣmaśarīra (Sanskrit सूक्ष्मशरीर).

Most Hindus and Jainas assume that the material body is associated with a subtle body. This contains souls inside that have existed for eternity, which are enveloped by a subtle body. When the associated gross body decays, these subtle bodies enter a new womb (reincarnation).

In these religions being consists of several factors of existence Tattvas (Sanskrit तत्त्व), in Sankhya there are 25 in number. 18 of these belong to the subtle body. These are the intellect Buddhi (Sanskrit बुद्धि), the ego center Ahamkara (Sanskrit अहंकार) and the thinking Manas (Sanskrit मनस्). From these, the five sensory abilities and the five action abilities should have further developed. Then the five subtle elements sound, touch, shape, taste and smell should have emerged. All these areas of sensation are said to belong to the subtle body.

In some interpretations of Vedanta there is a third causal body, Karana-Sharira (Sanskrit कारणशरीर), in addition to the material and subtle body, which causes Avidya and entanglement in samsara.

There are also subtle ideas in the Bhagavad Gita . For example, in Swami Prabhupada's formulations it says: “ The Supreme Truth exists inside and outside of all living beings, those who move and those who do not move. Because of their subtle nature, it is not possible to see or know you with the material senses. "

In most of the classical Hindu teachings, the life energy Prana (Sanskrit प्राण), which roughly corresponds to the Chinese concept of Qi ( Chinese 氣 / 气 ), is not subtle . These energies should have neither a physical nor a spiritual nature. In many esoteric adaptations of these teachings, however, Prana and Qi are also of a subtle nature.

In Mahayana -Buddhismus is taught that Buddha three Kaya had -Leibe (Sanskrit काय): a physical body Nirmana-kaya (निर्माणकाय) that appears on the earth, a subtle sambhoga-kaya (संभोगकाय), the supernatural in the worlds appears, and a Dharma-kāya (धर्मकाय), which as an absolute entity goes beyond all descriptions and personification and rather refers to the Dharma (Sanskrit धर्म), ethics.

Tantrism

In tantrism it is assumed that the body is pervaded by a system of subtle energy centers, the chakras , and energy channels , the nadis . The universal life energy, the prana, flows through these channels. They connect the gross body with the subtle body that surrounds it and is called Purusha or Atman . The chakras themselves are the abode of various gods, Shakti , the mother god, for example an ethereal force called Kundalini , which is located at the base of the spine. These subtle centers could be stimulated by certain exercises, especially Kundalini Yoga ; this could lead to spiritual healing or the opening of the “ third eye ” through which the subtle world could be perceived. The much younger Sahaja Yoga also tries to stimulate subtle body centers.

It is irrelevant whether the concept of subtle matter, for example in the chakras , nadis, is exclusively esoterically derived from the coherent system of tantras or whether there can or will actually be evidence based on empirical-scientific thinking, in the sense that it can be found physically, it is crucial that they can be experienced and effective through imagination in meditative practice or the healing ritual .

Esoteric

Many esoteric concepts are derived or adopted directly from religious ideas ( syncretism ). For example, the Huna esoteric is an interpretation of the Hawaiian religion , in which subtle concepts are represented as in the other Polynesian religions . Tantristic teachings and thus also neotantra are esoteric interpretations of Hindu and Buddhist elements.

Significance in traditional Polynesian religions

Subtle concepts are also important in the ancient religions of Polynesian culture . These beliefs are determined, among other things, by two opposing forces - mana and taboo . The mana is comparable to the eastern conceptions of prana or qi. It denotes a power of a spiritual or worldly nature. The taboo, on the other hand, is a strong prohibition or ban. Both powers are subtle in these beliefs and therefore invisibly exist and at the same time extremely effective.

Huna

In the Huna doctrine, which interprets the ancient Hawaiian religion , it is postulated that the entire real world is permeated by a subtle substance called "Aka" . A subtle matrix, the so-called shadow body, should consist of this Aka-substance, which depicts every concrete appearance like a blueprint . This applies not only to the physical appearance of things, but also to fleeting appearances, such as human thoughts and feelings. If this matrix changes now, the reality will also change.

Other ideas

One technique that is supposed to make subtle phenomena visible is the Kirlian photography developed by Semjon and Valentina Kirlian . A few esotericists and alternative physicians claim that the corona discharges in the pictures show the subtle aura of the matter depicted. The dowsing or Radionics tried to make subtle phenomena measurable.

Ellen Greve, who calls herself Jasmuheen , spreads the theory that people could use light fasting to nourish themselves on subtle matter that comes to earth with the light of the sun in prana and thus could do without conventional coarse food. Light fasting has been blamed for some starvation deaths.

Charles Richet explained at the end of the 19th century that there was a subtle ectoplasm that was secreted by media during contact with supernatural beings. These are materializations of spirits. Such phenomena have been photographed but are not scientifically explained or recognized.

Subtle ideas are also widespread in parts of alternative medicine. Representatives of the Bach flower therapy refer to the non-measurable subtle contents of the available drugs or essences. These subtle ingredients should be able to act directly on the soul. With the sound massage , subtle blockages are to be released. There is also a subtle substance called Ojas in Ayurvedic nutrition . Evidence about placeboide medical effectiveness of these therapies do not exist.

literature

- George R. Stow Mead : The Subtle Body Doctrine in the Western Tradition. Spirit bodies, radiant bodies and resurrection bodies in the world of experience of the Pythagoreans, Neoplatonists, Gnostics and Hermetic philosophers. Ansata, Interlaken 1991, ISBN 3-7157-0150-1 . (The original edition was published in English in 1919: The doctrine of the subtle body in western tradition. An outline of what the philosophers thought and Christians taught on the subject. Watkins, London 1919)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Roland Biewald: Small Lexicon of Occultism. Militzke, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-86189-627-3 , p. 619 (sv astral ) and 791 (sv subtle ). Digitized edition at Directmedia, Berlin 2006.

- ↑ Annie Besant: The Sevenfold Nature of Man. Adyar Verlag, Graz 1985, p. 15

- ↑ Rudolf Steiner: Akascha Chronicle. P. 55

- ↑ Christof Rapp , Christoph Horn : Vernunft; Understanding. In: Joachim Ritter , Karlfried founder (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of philosophy. Volume 11: U - V. Completely revised edition of the "Dictionary of Philosophical Terms" by Rudolf Eisler . Schwabe, Basel a. a. 2001, ISBN 3-7965-0115-X , p. 757.

- ↑ a b c d e f Jens Halfwasser: Soul car. In: Joachim Ritter, Karlfried founder (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of philosophy. Volume 9: Se - Sp. Completely revised edition of the “Dictionary of Philosophical Terms” by Rudolf Eisler. Schwabe, Basel et al. 1995, ISBN 3-7965-0115-X , p. 112 f.

- ↑ a b Helmut Riedlinger: Generatianism and Traduzianism. In: Joachim Ritter, Karlfried founder (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of philosophy. Volume 9: G - H. Completely revised edition of the "Dictionary of Philosophical Terms" by Rudolf Eisler. Schwabe, Basel a. a. 1974, ISBN 3-7965-0115-X , pp. 272 f.

- ↑ Tertullian : About the soul (de anima). In: Tertullian's all writings. Volume 2: The dogmatic and polemical writings. Translated from Latin by Karl Adam Heinrich Kellner. DuMont-Schauberg, Cologne 1882, p. 299, (online) , accessed on July 19, 2013.

- ↑ Tertullian: About the soul (de anima). In: Tertullian's all writings. Volume 2: The dogmatic and polemical writings. Translated from Latin by Karl Adam Heinrich Kellner. DuMont-Schauberg, Cologne 1882, p. 332, (online) , accessed on July 19, 2013.

- ^ René Descartes : Philosophical works. Department 3: Principia philosophiae (= Philosophical Library. Vol. 26, T. 2). Translated, explained and provided with a biography of Descartes by Julius Hermann von Kirchmann . Heimann, Berlin 1870, p. 176 ff. Zeno, Digitale Bibliothek , accessed on July 19, 2013.

- ^ Stephan Meier-Oeser: Subtility. In: Joachim Ritter, Karlfried founder (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of philosophy. Volume 10: St - T. Completely revised edition of the “Dictionary of Philosophical Terms” by Rudolf Eisler. Schwabe & Co., Basel et al. 1998, ISBN 3-7965-0115-X , p. 563 ff.

- ↑ Walter Sparn: Immortality. In: Joachim Ritter, Karlfried founder (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of philosophy. Volume 11: U - V. Completely revised edition of the "Dictionary of Philosophical Terms" by Rudolf Eisler. Schwabe, Basel et al. 2001, ISBN 3-7965-0115-X , p. 286.

- ↑ Kurt Galling (ed.): The religion in history and present. Concise dictionary for theology and religious studies. Volume 5: P - Se. 3rd, completely revised edition. Mohr, Tübingen 1961, p. 1366 (also: (= digital library. Vol. 12). Unabridged electronic edition of the 3rd edition. Directmedia, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89853-412-X ).

- ↑ Lambert Schmitshausen: avidyā. In: Joachim Ritter, Karlfried founder (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of philosophy. Volume 1: A - C. Completely revised edition of the "Dictionary of Philosophical Terms" by Rudolf Eisler. Schwabe & Co., Basel et al. 1971, ISBN 3-7965-0115-X , p. 736.

- ↑ Kurt Galling (ed.): The religion in history and present. Concise dictionary for theology and religious studies. Volume 5: P - Se. 3rd, completely revised edition. Mohr, Tübingen 1961, p. 1638 (also: (= digital library. Vol. 12). Unabridged electronic edition of the 3rd edition. Directmedia, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89853-412-X ).

- ^ Helmuth von Glasenapp : The philosophy of the Indians. An introduction to their history and their teachings (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 195 ). Kröner, Stuttgart 1949.

- ↑ Sri Srimad, AC Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupãda : Bhagavad-Gita as it is. With the original Sanskrit verses, Latin transcriptions, German synonyms, translations and detailed explanations . Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, Grodinge 1987, ISBN 91-7149-401-4 , pp. 614 .

- ↑ Manfred Kubny: Qi. Life force concepts in China. Definitions, theories and fundamentals . 2nd Edition. Karl F. Haug, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-8304-7105-X (Munich, University, dissertation, 1993).

- ^ Ainslie T. Embree, Friedrich Wilhelm: India. History of the subcontinent from the Indus culture to the beginning of English rule. (= Fischer world history. Vol. 17). 12th edition. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-596-60017-0 , p. 112 (Also: Fischer Weltgeschichte (= digital library. Vol. 19). Complete edition. Directmedia, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89853 -519-3 ).

- ↑ Ajit Mookerjee, Madhu Khanna: The world of Tantra in images and interpretation . Gondrom, Bindlach 1990, ISBN 3-8112-0702-4 .

- ^ Judith Coney: Sahaja Yoga. Socializing Processes in a South Asian new religious Movement. Curzon, Richmond 1999, ISBN 0-7007-1061-2 .

- ↑ Kundalini and the subtle system of the body. Text excerpt from Karin Brucker: The elemental force Kundalini: Recognize phenomena, interpret symptoms, master transformation. OW Barth, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-426-41037-0 , accessed October 13, 2018 [1]

- ↑ Serge Kahili King: Kahuna healing. The healing arts of the Hawaiians . Lüchow, Freiburg (Breisgau) 1996, ISBN 3-925898-58-1 .

- ↑ Helmut Uhlig: Life as a cosmic festival. Magical world of tantrism . Edited from the estate and provided with an essay by Jochen Kirchhoff . Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1998, ISBN 3-7857-0952-8 .

- ↑ Pierre Bettez Gravel: The malevolent eye. An essay on the evil eye, fertility and the concept of mana (= American University Studies. Series 11: Anthropology and Sociology. Vol. 64). Lang, New York NY et al. 1995, ISBN 0-8204-2275-4 .

- ↑ Serge King: Encounter with the hidden self. A workbook on Huna magic . 4th edition. Aurum, Bielefeld u. a. 2001, ISBN 3-89901-313-1 .

- ↑ Horst Wedekind: Kirlian photography self-made. Retrieved July 19, 2013 .

- ↑ Jörg Purner: Radiesthesia - “organ of perception” for a different reality? About research and experience on the subject of "radiation sensitivity". (PDF; 119 kB). Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ↑ Jasmuheen (Ellen Greve): Light nutrition. The source of food for the coming millennium . 3rd, revised edition. Koha, Burgrain 1997, ISBN 3-929512-26-2 .

- ↑ Sect insanity: disciples starve themselves to death . In: Berliner Kurier . September 27, 1999 ( (online) [accessed July 19, 2013]).

- ^ Nicolette Bohn: Lexicon of sects and psycho groups (= digital library . Special volume). Directmedia, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89853-033-7 , p. 754 (Also contains: Roland Biewald: Lexikon des Occultismus. ).

- ↑ Eberhard J. Wormer , Johann A. Bauer: New large encyclopedia medicine & health. Medicine from A to Z, symptoms from A to Z, laboratory and diagnosis, naturopathic treatments, anti-aging, medicinal plants, first aid (= digital library . Special issue). Directmedia, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89853-035-3 , p. 5195 .

- ^ E. Ernst: Flower remedies. A systematic review of the clinical evidence. In: Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. Vol. 114, No. 23/24, December 2002, ISSN 0043-5325 , pp. 963-966, PMID 12635462 ; Aijing Shang, Karin Huwiler-Müntener, Linda Nartey, Peter Jüni, Stephan Dörig, Jonathan AC Sterne, Daniel Pewsner, Matthias Egger: Are the clinical effects of homoeopathy placebo effects? Comparative study of placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy and allopathy. In: The Lancet. Vol. 366, No. 9487, 2005, ISSN 0140-6736 , pp. 726-732, PMID 16125589 , doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (05) 67177-2 .