Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim

Heinrich Cornelius, called Agrippa von Nettesheim - Latinized Henricus Cornelius Agrippa from / de Nettesheym / Nettesheim (born September 14, 1486 in Cologne , † February 18, 1535 in Grenoble ) - was a German polymath , theologian , lawyer , doctor and philosopher . In his exploration of magic , religion , astrology , natural philosophy and his contributions to the philosophy of religion, he is one of the most important scholars of his time.

Life

Heinrich Cornelius came from an impoverished noble family from Cologne. He had a sister. Nothing is known about his childhood and early adolescence. The III. The register of the University of Cologne records the matriculation of Henricus de Nettesheym, son of the father of the same name, who, as a citizen of Cologne, may have been in the service of the House of Austria, at the Faculty of Liberal Arts on July 22, 1499 . Heinrich Cornelius, known as Agrippa von Nettesheim, was admitted to the baccalaureate on May 29, 1500 in the IV. Dean's Book of the Artist Faculty . An entry from July 1, 1500 records the beginning of the determination and on March 14, 1502 the admission to the licentiate examination . Nothing is known about other university degrees in Cologne. The self-paced curriculum Agrippa included Latin , astrology, theology, basics of magical thinking, hermetic books, Orphic hymns , Kabbalah, Roman law , medicine, mechanics , optics and geometry . In 1502 or 1503 he changed his place of study and traveled to Paris, the oldest known and surviving letters date from 1507. From this it emerges that he was in personal relationship with personalities such as Charles de Bouelles , Germain de Ganay , Germain de Brie , Symphorien Champier and Jean Perréal and with some of them in Paris at times formed a kind of brotherhood ( sodalitas ), which he later of Hoping to revive southern France out in the event of a return to Paris. With financial support from wealthy citizens, he also carried out the first extensive alchemical experiments during this time.

In 1508 he traveled to Spain with friends and hired a number of mercenaries to recapture the castle after a cry for help from his friend, the Basque Janotus . After the victory, however, the tide turned because an overwhelming number of discontented peasants surrounded the castle, the last refuge was a tower and starvation threatened. Agrippa let a soldier, whose face he had artificially applied the horror marks of the plague , walk among the besieging peasants who were fleeing in a panic of infection. Agrippa, his friends and the mercenaries managed to escape. After living in Lyon and Autun plagued by financial difficulties Agrippa held in the spring of 1509 as a lecturer and professor at the University of Dole lectures on John Reuchlin work De verbo mirifico , at the invitation of the chancellor of the university and the archbishop of Besancon Antoine I. de Vergy . Since he apparently had a steady income again, his lectures were offered free of charge.

The lectures met with great interest, but also strong criticism from the Provincial of the Burgundian Franciscans , Jean Catilinet . During a fasting sermon in Ghent , at which the regent Margaret of Austria and her court were among the audience, Catilinet described Agrippa as a " Judaizing heretic ". Agrippa left Dole after a while and traveled to England. Here he wrote a letter of justification to Catilinet a year later, which was also printed in the collected treatises of 1529 under the title Expostulatio cum Joanne Catilineti .

While still in Dole, Agrippa also wrote a Declamatio de nobilitate et praecellentia foeminei sexus in praise of the female sex. Topics are historical achievements of women, criticism of upbringing and much more. One thesis is that women are incorruptible, which is why the culture of corruption in church and state is a purely male domain. Agrippa tried to secure the favor of Margarete of Austria and thus also a permanent academic position at the court through this writing. Jean Catilinet, who was also court preacher, prevented the printing of the script and the honorable office at court.

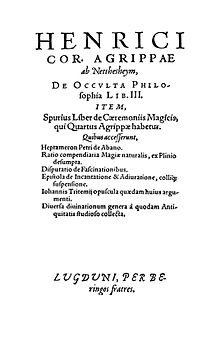

Back in Cologne at the end of 1509, Agrippa made contact with the famous scholar, witch theorist and abbot Johannes Trithemius of the Benedictine monastery in Sponheim , who had been abbot at the Schottenkloster in Würzburg since 1506 , which was followed by a long working visit from Agrippa. During this meeting Agrippa wrote with Johannes Trithemius and at his suggestion up to the spring of 1510 his main three-volume work entitled De occulta philosophia ("About the secret philosophy") on the magic known up to that point, a systematic summary for the first time through verification and classification of this Knowledge of its time. “ This learned compendium of gigantic proportions formed the basis for early fame and hasty slander, although this work too did not appear in print until decades later. "

At the turn of the year 1509/10, Agrippa, who was also interested in mineralogy , must also have been active as a mountain ridge for the city of Cologne , which is evident from a remark in the work De incertitudine et vanitate scientiarum ("On the uncertainty and vanity of the sciences") emerges. Emperor Maximilian I sent many representatives to England in 1510 in order to have a direct impact on King Henry VIII's policy . Agrippa was chosen by the emperor because of his talent for languages (he spoke eight languages, six of them fluently) and sent to England with secret imperial instructions . Here Agrippa also attended the lectures given by the humanist John Colet at Oxford University on the mysterious peculiarities of Pauline Christianity. Agrippa stayed for some time at the invitation of the scholar John Colet in his house in London. Back in Cologne he held lectures at the university in 1511, in the style of a quodlibetan (“What you want”) opinion on theology. During this time the dispute between the Cologne Dominicans , including Johannes Pfefferkorn , began against the scholar Johannes Reuchlin. Agrippa also took a stand on this dispute and accused the opponents of Johannes Reuchlin's ignorance. This dispute, which for years was waged by many important scholars at many universities, extended to the later dark man letters .

In the same year he traveled to Italy, according to his own statements in Trieste, to accompany a heavily guarded war chest through the country as an imperial officer. At the end of 1511 he took part in the Council of Pisa at which he, like many other theologians, was excommunicated under the pontificate of Pope Julius II . It was probably an excommunicatio ferendae sententiae , i.e. an excommunication due to the public dispute with representatives of the Catholic Church. At the beginning of 1512 he traveled to Pavia and gave lectures at the university there on the philosopher Plato and his work Convivium Phaedrus . In mid-1512 he fought as an officer in the army of Emperor Maximilian I against the Venetians and was knighted, Eques auratus , on the battlefield for bravery in front of the enemy . In 1513 he accompanied the Cardinal of Santa Croce to the Council in Pisa, where Giovanni de 'Medici was elected Pope Leo X , on diplomatic missions en route as a theologian . After the election of Pope Leo X, Agrippa's excommunication was lifted by a reconciliation . Agrippa, who tried to settle his disputes with scholars and representatives of the Church at the council, was not of much use to even a letter of praise from the new Pope to smooth things over. In 1514 Agrippa deepened his knowledge and wandered through Italy. In 1515 he gave lectures in Pavia on Hermes Trismegistus and the magic and revelation books ascribed to him, essentially the hermetic writings Picatrix and Pimander from the Corpus Hermeticum . In the same year Agrippa married in Pavia; The name and origin of his wife are unknown.

Agrippa of Nettesheim also became medicinae Doctor and Doctor iuris utriusque at the University of Pavia doctorate (the current research results are pros and cons to; that he received his doctorate, is evident from the fact that he was appointed by the respective city councils, and He did this in very important and sought-after positions, such as syndicus in the imperial city of Metz , city doctor of Freiburg and later city physician and director of the city hospital in Geneva, which he would not only have received without an academic title, but also those given the number of his learned opponents would have been unsustainable). At the end of 1515, Pavia was facing the fall of the advancing French army, Agrippa lost his belongings and fled with his wife towards Piedmont . In 1516 he wrote the treatise De triplici ratione cognoscendi Deum , probably at the castle of his patron Marquis de Montferrat. Abbot Trithemius, who owned one of the most extensive libraries with 2,000 books and writings, died in December 1516, and made Agrippa his heir to some of them. Agrippa became a father in 1517: his wife gave birth to a son named Aymont. After staying in various cities in Italy, Agrippa traveled to Cologne in 1518. He received the offer to work as the papal legate in Avignon , but decided in favor of the offer as city attorney and keynote speaker for the wealthy trading city of Metz.

Arrived in Metz in February 1518 with his wife and child, he went about his work as a syndic and also wrote the treatise De originali peccato . He studied the writings of Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples , whom he also defended in public from the clergy . Here Agrippa, who also dealt with the Reformation , bought books and writings from Martin Luther , Erasmus of Rotterdam, Lefèvre d'Étaples and others to distribute to his learned friends. The fact that he did it at his own expense continued in Geneva and Freiburg. In 1519 his father died in Cologne. In Metz, Agrippa was chosen by the city officials to defend a woman from the village of Woippy who had been accused of witchcraft before the inquisitor Claudius Salini . A conviction was assumed, so Agrippa was given free choice in his defense. In the dragging process, Agrippa managed to refute the inquisitor reciting from the witch's hammer ( Malleus maleficarum) , and the woman was acquitted. As a result, Agrippa fell out of favor even with the authorities and city lords in Metz. Public disputes with the clergy and the rumors of ordinary citizens (“Whoever wins against the Inquisition can only be a member of the devil”) made life in Metz increasingly difficult. Rumors spread throughout the city that Agrippa himself was a black or devil artist who secretly conjured up magical spirits. “ This laid the foundation for a legend that Agrippa was to pursue beyond the grave throughout his life. "

On January 25, 1520 he left Metz and traveled to Cologne, where he wrote the pamphlet De beatissime Annae monogamia . In July of that year he met the anti-clerical imperial knight and leading reformer Ulrich von Hutten in Cologne . Agrippa was also given the magical part of the books and writings from the legacy of Trithemius at the time. In 1521 he traveled to Metz to visit old friends; unfortunately his wife died unexpectedly during this stay. Agrippa traveled on to Geneva with his 4 year old son and worked there as a doctor. At the end of 1521, Agrippa married 18-year-old Jana Luisa Tissie from a noble Geneva family who had a total of 6 children from him. In 1522 Agrippa was appointed director of the Geneva City Hospital. In 1523 the city lords of Geneva tried in vain to persuade Agrippa to stay, because they saw in him a leading scholar of their time. In the same year Agrippa moved on to the Swiss town of Freiburg im Üechtland , where he became a city physician , deepened his occult studies and met agents of the Duke of Bourbon, who was an enemy of King Francis I. In Freiburg, Agrippa wrote an open letter of defense for his long-dead old master Trithemius, who has meanwhile been defamed as a black magician and a fraud. Since Agrippa did not want to gild pharmacists' tills in Freiburg by issuing expensive and unnecessary prescriptions, he issued poor people his own prescriptions or treated them for free. In doing so, he turned an alliance of doctors and guild pharmacists against him, which in July 1523 prompted him to submit his dismissal to the magistrate himself.

Arrived in Lyon in 1524 , he accepted the post of personal physician to Luise von Savoyen , mother of King Franz I, in May . Agrippa's second son Henry was born in Lyon, followed in 1525 by his third son Jean. In 1526 he wrote the treatise " Declamatio de sacrameto matrimonii ". That year his salary at court was not paid properly and regularly, he first had to write begging letters and then threatening letters to the tax authorities, which was of no use. This also began the intrigues at court against Agrippa, in addition to which Regent Luise demanded horoscopes about her son Franz I from him, which he tried to refuse on the grounds that there were probably more important things to do. Probably in order not to fall completely out of favor, he created a horoscope for the further events of the war, but astrologically prophesied the victory of the enemy, namely the victory of the House of Bourbon. Agrippa completed the second major work De incertitudine et vanitate scientiarum here. Presumably seeing the end in Lyons and avoiding the intrigues against himself, he secretly negotiated with emissaries from Charles I , Duke of Bourbon, for a position at court. In 1527 Agrippa learned that he had been removed from the payroll , although he was still the personal physician of the king's mother.

Since negotiations for a job with the Duke of Bourbon were unsuccessful, he and his family traveled to Paris at the end of that year. In March 1528 he received the passports for himself and his family in Paris, which he needed for the onward journey and the associated border crossing to Antwerp . At the end of 1528 Agrippa began working as a doctor in the city of Antwerp, while wealthy citizens financed him for joint alchemical and mechanical experiments. In order to improve his financial situation, he also passed on his knowledge or issued horoscopes to people from all walks of life, even monks were among them. He got himself into trouble in Antwerp by pleading for the free choice of doctor and defending a man who practiced as a medicus without the permission of the faculty. Agrippa tried unsuccessfully to secure the office of personal physician to Margaret of Austria. At the beginning of 1529 Agrippa became a father for the seventh time. Some tracts and other writings by Agrippa have also been published in book form under the publisher Michael Hillenius. The plague had broken out in Antwerp and on August 17th his wife died of it, and several employees from his servants were killed by the plague. Agrippa stayed and took care of the plague sufferers in the city, but had his children brought from Antwerp. At the end of the year he received an offer from Henry VIII to travel to England to work for him as a lawyer. Agrippa, however, decided on the position of Imperial archivist and historiographer in Mechelen for Margaret of Austria, regent of the Netherlands, a position that he took up in 1529.

In February 1530 Agrippa wrote an official report on the coronation ritual of Charles V as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and King of Lombardy . For the edited two major books De incertitudine et vanitate scientiarum and De Occulta Philosophia and some of his other writings, he got after long negotiations the Imperial privilege to print his works. In the middle of 1530 the book De incertitudine et vanitate scientiarum was printed and published by Agrippa's publisher Cornelius Grapheus in Antwerp. This book spread very quickly among European scholars. It became a contemporary bestseller that had over ten editions within five years. In this book, which, like De Occulta Philosophia, also took a critical look at the low level of science (including in the field of medicine), he also attacked the ecclesiastical and political conditions of his time and thus directly the clergy and the caste of court officials and officials of the Rulers. Agrippa also described his own work self-critically in this book. ( One could believe that Agrippa had mastered so many arts just to be better able to discard them in the end .)

The clergy of the Catholic Church, who wanted to ban the book, saw only "heresy and heresy" in this work. In order to clarify the theological and legal questions, the University of Leuven was called in , but they also condemned this book in the strictest terms. The emperor demanded that at least the criticism of the church and the clergy be revoked. Agrippa refused to do this, so that the emperor was forced to stop paying Agrippa any more wages. The court in Mechelen was not long in coming, then he was requested in a written indictment not to publish the book further. Agrippa wrote a counter-writ in the form of an Apologia , in which he refuted each charge individually, so that his book was not banned from printing. Even Erasmus was personally a copy of letter from Agrippa sent. Erasmus received a lot of praise for the book, but at the same time urged Agrippa to be more careful with his comprehensive criticism. While traveling through Brussels at the end of 1530 , Agrippa was imprisoned on a pretext and then thrown into the guilt tower. At the same time the magistrate of the city of Brussels and the city's religious overseers had some copies of De Incertitudine et vanitate scientiarum publicly burned. Agrippa was released after a while, on condition that he leave Brussels immediately. Back in Mechelen, Agrippa wrote a funeral oration and a panegyric for the regent Margarete, who died on December 1, 1530.

During his time in Mechelen, he married a third time, the name and origin of his wives are not known. On March 2, 1531, the Sorbonne University in Paris officially condemned the French edition of De Incertitudine et vanitate scientiarum as the work of a heretic. " Scripture is close to Lutheran heresy, it criticizes, among other things, institutions of the church and must therefore be handed over to the fire ". The Erasmic humanist Louis de Berquin , although he was under the personal protection of King Francis I, was indicted by the Sorbonne in 1529 and then executed. So Agrippa looked for new protection for himself and traveled to Cologne. From March 1532 he stayed for a few months at the country residence of Archbishop of Cologne Hermann von Wied , where he was able to recover from clerical and university feuds. The papal legate, Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggi, defended him, probably also to induce him to publish a pamphlet against Henry VIII and his divorce matters; Agrippa did not accept this offer. Another proponent in favor of Agrippa and his criticism was the Cardinal Erard de La Marck . Agrippa died on February 18, 1535 at the age of 48 in Grenoble. Agrippa's burial took place at a Dominican convent; he was given his final resting place in a Dominican church.

Three sons survived him and became citizens of Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye , but they did not use the name "von Nettesheim" and called themselves Cornelis, Corneille or Cornelius. A stranger came up with something special for the inscription on his tombstone, because on this one found strange words, among other things, the inscription said that the suitable place for Agrippa would be Hades . Agrippa owned a black dog, which he called "Monsieur", who was even equated with Kerberos , as his epitaph shows. The Dominican Church no longer exists, it was destroyed by Protestants in 1562. The tombstone itself changed several monasteries where it was kept until the track is lost.

Encounter with Dr. fist

Agrippa and the historic Dr. Johann Faust is said to have met each other in 1532. Johann Weyer , a pupil of Agrippa, wrote with his book De praestigiis daemonum a fundamental work for the defense of persons accused of witchcraft . In connection with the psychological mechanism of suggestion examined by Agrippa (as well as Paracelsus and others) as "imagination", Weyer saw the persons concerned not as allies of the devil, but as afflicted with mental illness. The universal scholar Agrippa von Nettesheim partly inspired Johann Wolfgang von Goethe not only with his writings to design the Faust drama.

Cosmology and theory of the soul

At the age of twenty-three, Agrippa wrote his early work De occulta philosophia . In it he systematically placed astrology , Kabbalah , theology , mantic , evocation magic , angelology , amulet and talisman magic side by side and defended his “holy magic” in an elegant style against “magicians” and “devil conjurers”. In its time this was life-threatening and sensational for its readers. That is why three editions appeared in Antwerp, Paris and Cologne (1530–1533) in just three years.

“The magical science, which has so many powers at its disposal, and which has an abundance of the most sublime mysteries, comprises the deepest contemplation of the most hidden things, the essence, the power, the nature, the substance, the force and the knowledge of all nature . It teaches us to know the diversity and the correspondence of things. Hence its wonderful effects; by uniting the most varied of forces with one another and everywhere combining and marrying the corresponding lower with the gifts and powers of the upper. Science is therefore the most perfect and highest, it is a sublime and holy philosophy, yes it is the absolute perfection of the noblest philosophy. "

In De occulta philosophia Agrippa represents a Neoplatonic worldview. He retained the views outlined there, at least until the Declamatio was drafted (“The vanity and uncertainty of science and the defense document”). On the one hand, this work speaks of Father, Son and Holy Spirit ; on the other hand, the concept of God is also Platonic or rather Neo-Platonic in the ancient (pagan) sense. Because Agrippa also speaks of a God in whom all things are present as ideas. The doctrine of ideas was also understood by Christian Neoplatonists like Augustine in a similar way. What Augustine no longer represented, however, is the concept of the world soul . This comes from the Timaeus of Plato and was adopted by Plotinus in Neoplatonism . In contrast to the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, Plotinus regards the divine hypostases ( the one , the spirit and the world soul) as hierarchical. At the top of the hierarchy is the one (God) from whom everything else emerges and into which everything returns. The one is unity, while the spirit or the world soul are already "two". The doctrine of the “trinity” speaks of a “triune” God, who in turn is no longer to be thought of as strongly hierarchical as in Plotinus' neo-Platonism. In addition, the Greeks (Plato, Plotinus, Proclus , Porphyry etc.) do not see God as a “subject”.

What distinguishes Agrippa from medieval Neo-Platonism (Augustine, Eriugena, etc.) is the idea that the cosmos is permeated by the forces of the archetype. In a certain way, God is also “in the world”. The world as a whole can be viewed as the “incarnation of God”. Other Neoplatonists speak of the image of God (including the Christian ones). In this respect, the difference to Christianity is always very small, and therefore Agrippa was possibly also able to escape the Inquisition. Agrippa also advocates a “ panpsychism ”, and this distinguishes him from both Plotinus and Christian Neo-Platonists of the Middle Ages. In chapter 56 of the "Occulta philosophia" it says:

"If the world body is a whole body, the parts of which are the bodies of all living beings, and there, the more perfect and noble the world body is than the body of the individual beings, it would be absurd to assume that if every imperfect body and world particle [... ] Owns life and has a soul, the whole world as the most perfect and noble body neither lives nor has a soul. "

The world soul is implicitly referred to here. At the same time it becomes clear that all things have a soul (including matter), and with this Agrippa clearly contradicts medieval ideas. Even with Plotinus, matter ( evil ) was inanimate. Panpsychism is a typical characteristic of the Neo-Platonism of the Renaissance.

In this view of the world, man is the image of God and represents a microcosm. Therefore Agrippa also assigns the individual limbs and organs of the human body to certain stars, such as B. the spleen to Saturn or the right ear to Jupiter. He leans very closely on the teaching of Averroes (Ibn Ruschd) when he speaks of the four inner senses (common sense, imagination, fantasy, memory). In the doctrine of the soul, too, Agrippa always tries to keep his doctrine in harmony with the Christian one, which of course does not always succeed.

Agrippa's statements about the state of the human soul after death remain contradictory. He points to the doctrine of "retribution" (reincarnation) without expressing himself on the stated opinion (Chap. 41 De occulta philosophia):

“In this way, the great Origen believed , the words of Christ in the Gospel should also be interpreted: Whoever takes the sword, he shall perish by the sword. The pagan philosophers also believe in such retribution and call it Adrastea, i.e. the power of divine laws, according to which in future times everyone will be rewarded according to the nature and the merits of his previous life, so that whoever ruled unjustly in the previous life in others Anyone who stains his hands with blood and has to suffer equal retribution gets into a state of slavery, and whoever led an animal life is locked up in an animal body. "

Editions and translations

Editions and translations from the 16th century

- Opera , Lyon 1550 (complete edition)

- De incertitudine et vanitate scientiarum ("On the uncertainty and vanity of science"), Cologne 1527 (a satire on the sad state of science, in which, as in Occulta philosophia, among other things, he criticized the urination methods of his time)

- Declamatio de nobilitate et praecellentia foeminei sexus (“Of nobility and primacy of the female sex”), Antwerp 1529 ( digitized BNF ; online text of the Latin version 1529 and the English translation London 1670)

- From the nobility and the female gender / Herr Henrici Cornelij Agrippe / Löblichs Büchlin. 1540 (translation of Declamatio de nobilitate et praecellentia Foeminei Sexus ), edited and commented by Jörg Jungmayr . In: Elisabeth Gössmann (Ed.): Archive for women's research in the history of philosophy and theology . Volume 4, Iudicium, Munich 1996 1988, ISBN 3-89129-004-7 , pp. 46-52 and 63-100.

- De occulta philosophia libri tres ("Three books on magic"), Cologne 1510, 1531 and 1533 ( digitized version )

Modern editions and translations

- Otto Schönberger (Ed.): H. Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim: De nobilitate et praecellentia foeminei sexus. Of nobility and primacy of the female sex. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1997, ISBN 3-8260-1262-3 (Latin text, translation and commentary)

- Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim, De occulta philosophia. Three books on magic. Franz Greno, Nördlingen 1987, ISBN 3-89190-841-5 (German translation by Friedrich Barth, 1855)

- Vitoria Perrone Compagni (ed.): Cornelius Agrippa: De occulta philosophia libri tres. Brill, Leiden 1992 (critical edition)

- Marco Frenschkowski (ed.): The magical works. Marixverlag, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-86539-153-7 .

- Agrippa von Nettesheim: About the questionability, even nullity, of the sciences, arts and trade. With an afterword ed. by Siegfried Wollgast . Translated and with comments by Gerhard Güpner. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1993.

literature

- Heinrich Grimm: Agrippa von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6 , p. 105 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Marc van der Poel: Cornelius Agrippa, The Humanist Theologian and His Declamations . Brill, Leiden / Boston 1997.

- Hermann FW Kuhlow: The Imitatio Christi and its cosmological infiltration. 1967.

- Charles G. Nauert Jr .: Agrippa and the Crisis of Renaissance Thought (= University of Illinois Studies in the Social Sciences 55). Urbana 1965 (standard biography)

- Paola Zambelli: Agrippa von Nettesheim in the more recent critical studies and manuscripts. In: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 51, 1969, pp. 264–295.

- Wolf-Dieter Müller-Jahncke : Magic as a science in the early 16th century. The relationships between magic, medicine and pharmacy in the work of Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535) , dissertation University of Marburg 1973.

- Wolf-Dieter Müller-Jahncke: Agrippa von Nettesheim, Cornelius. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 19 f.

- Michael Kuper: Agrippa von Nettesheim - a real fist. Zerling, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-88468-056-0 .

- Rosemarie Schuder : Agrippa and The Ship of Satisfied People. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1977

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 63-64.

- Roman Bösch : Agrippa's dream - news from a dark time . Edition fabrica libri (Pomaska-Brand Verlag), Schalksmühle 2012, ISBN 9783935937856

Web links

- Literature by and about Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim in the German Digital Library

- Works by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim at Zeno.org .

- Detailed biography of the IMBOLC magic school on magieausbildung.de

- Henry Morley, The life of Henry Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim

- Brief description of life and work in Historicum.net

- Extensive historical biography ( memento from October 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Stanford University biography

- Writings of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (English)

Remarks

- ^ A b Michael Kuper: Agrippa von Nettesheim - A real Faust. Zerling, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-88468-056-0 , p. 10.

- ↑ a b plato.stanford.edu

- ↑ Michael Kuper: Agrippa von Nettesheim - A real Faust. Zerling, Berlin 1994, p. 12.

- ^ Emmanuel Faye: Philosophy et perfection de l'homme: De la Renaissance à Descartes. Vrin, Paris 1998, p. 86.

- ↑ Theological Real Encyclopedia Volume 2, p. 191.

- ↑ bautz.de ( Memento from June 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ phil-fak.uni-duesseldorf.de

- ↑ Magic in the library . In: Insight.

- ^ Institute for Frontier Areas of Science: Lexicon of Paranormology. ISBN 978-3-85382-081-0 .

- ↑ Trithemius .

- ↑ Michael Kuper: Agrippa von Nettesheim - A real Faust. Zerling, Berlin 1994, pp. 81-82.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki : Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. Ernst Giebeler, Darmstadt 1982, ISBN 3-921956-24-2 , p. 148 f.

- ↑ Michael Kuper: Agrippa von Nettesheim - A real Faust. Zerling, Berlin 1994, p. 116.

- ↑ Erwin H. Ackerknecht : History of Medicine. 5th, revised and supplemented edition of Brief History of Medicine (Stuttgart 1959), Enke, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-432-80035-5 , p. 91.

- ↑ uni-stuttgart.de

- ↑ De occulta philosophia, Book I, K. 2, p. 13.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Agrippa von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Nettesheim, Henricus Cornelius Agrippa from |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Polymath, theologian, lawyer, doctor and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 14, 1486 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cologne |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 18, 1535 |

| Place of death | Grenoble |