inspiration

Under inspiration ( Latin inspiratio , inspiration ', Exhale, made in , inside' and spirare , breathe 'breathe.'; Cf. spirit , breath ',' soul ',' spirit ') is generally understood linguistically an inspiration about an unexpected idea or a starting point for artistic creativity . The conceptual history is based on the idea that on the one hand works by artists and on the other hand religious traditions are inspirations of the divine (not necessarily understood personally) - an idea that is found in both Near Eastern religions and pre-Socratic philosophers and then develops a broad history of impact.

Concept history

Hesiod and Democritus saw themselves as recipients of divine inspiration. Democritus put it: "Whatever a poet writes with enthusiasm (literally: divinity, indwelling of the divine) and with a divine touch or spirit (met 'enthousiasmou kai hierou pneumatos), that is certainly beautiful."

Cicero uses the Latin expression afflatus in the poetic as well as in the religious sense for "inspiration" or "divine inspiration".

Artistic inspiration

In poetry, the terms inspiration or afflatus symbolize the "blowing in, breathing in of something" by a divine wind. Cicero often speaks of the idea as an unexpected breath (cf. Pneuma ) that overtakes the poet - a powerful force, the essence of which the poet is helplessly and unconsciously exposed.

In this literary form, "Afflatus" is mainly used in English , less often in German and other European languages, as a synonym for "inspiration". In general, it does not refer to an ordinary sudden, unexpected, original idea, but rather the overwhelming of a new idea in a wavering moment - an idea, the origin of which usually remains inexplicable to the recipient.

Even with Plato , a critical reflection of the self-image of poets, which appeals to divine input, begins (in Phaedrus ). Yet Marsilio Ficino and other Renaissance poets, in their attempts to revive the idea of the divinity of poetry, rely less on Plato's criticism of poetic enthusiasm than on his enthusiastic description. The source of inspiration shifts in classicism and the genius period of the 18th century: it is the poets of earlier times whose work one is moved and inspired by (as with JJ Winckelmann ).

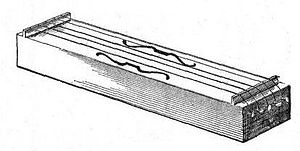

In Enlightenment and Romantic literature , the use of the term afflatus was occasionally revived as a mystical form of poetic inspiration by literary genius . The frequent use of the Aeolian harp as a symbol for the poet is an allusion to the revived use of the afflatus.

Since the late 19th century, the aesthetic of inspiration was rejected, especially in France: Baudelaire describes Edgar Allan Poe's style as a law linked to logic, Paul Valéry writes about Degas , whose paintings are a result of arithmetic operations.

On the one hand, Nietzsche referred to all great artists as great workers. On the other hand, in Ecce Homo, he also describes the experience and the idea of inspiration, as did Rainer Maria Rilke , Stefan George and artists of surrealism such as André Breton and Max Ernst , who emphasized that the artist is not a creator, but rather in the 20th century just watch the creation of his dream-inspired work as a pure “spectator”.

Inspiration in the religions

Christianity

In the context of Christian theology it is taught (officially by all Christian churches ) that the Bible is inspired and inspired in a special way by God's spirit (Latin divinitus inspirata , Greek θεόπνευστος / theópneustos , literally breathed on by God ). That is why the Bible is also called the Word of God .

Overview

This doctrine of inspiration is interpreted differently in detail:

- Under the assumption of verbal inspiration , the very text of the Bible is believed to be inspired by God . As a result, the Bible is assumed to be inconsistent and inerrancy. Even during the Reformation, theologians felt compelled to define the doctrine of inspiration, as the dispute between Protestants and the Roman Catholic Church had to clarify the question of the source of the Protestant doctrine of justification. Luther no longer needed them because he put the word of Christ at the center. Calvin , on the other hand, largely adhered to it and thus to the postulate that Scripture was inerrancy. After the Enlightenment onset scientific and critical research led to a further departure from the doctrine of verbal inspiration and to the conclusion that not all statements of the Bible have the same weight. In the Old Testament itself there are very few references to the fact that God instructed the prophets to write down his message . It should also be clarified which text is really the originally inspired version in view of the complicated authorship of most biblical books and their three different original languages ( Hebrew , Aramaic and Greek ).

- From the point of view of the advocates of the assumption of “real inspiration”, which has replaced the verbal inspiration thesis, (divine) facts or events (e.g. a prophecy or an experience of God ) revealed in the Bible were put into human words without being dictated literally.

- For the Protestant theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), the apostles, as original followers of Christ, were in a special way the bearers of the spirit that emanated from him; insofar they are inspired as persons, their generation of thoughts was inspired by the Holy Spirit. This understanding can be referred to as “personal inspiration”.

- The Catholic doctrine of inspiration is described after the Second Vatican Council in the third chapter of the Dogmatic Constitution on the divine revelation Dei Verbum . Accordingly, for the composition of the Holy Books , God chose ... people who, through the use of their own abilities and powers, were to serve him in writing down everything and only what he ... wanted to have written as genuine authors . It is to be confessed that the books of Scripture teach safely, faithfully and without error the truth that God wanted to have recorded in holy scriptures for the sake of our salvation (DV 11).

- Another understanding of inspiration does not take revelation in the sense of communicating a literal speech or a fact, but rather in the sense of God's self-revelation. Accordingly, the inspiration of the Holy Scriptures is that through it the reader (or listener) can experience that God speaks to him personally and awakens religious faith in him . This is also possible with other texts; According to this view, the special position of the Bible results from the fact that it also represents the original testimony of God's actions to man (especially in the person of Jesus Christ ).

- For today's so-called “faithfulness to the Bible” who adhere to the Reformed creed of “verbal inspiration”, the Bible is the only perfect and reliable revelation from God. Other possible revelations, such as “ speaking in tongues, ” which are not viewed by all “Bible-believers” as godly revelation, must be measured and judged against the standard of the Bible. For those who believe in "verbal inspiration," the original manuscripts of the Bible are considered to be the utterly infallible Word of God in every word, which makes the Bible their supreme authority.

Inspirational teaching of the Roman Catholic Church

The doctrine of inspiration of the Roman Catholic Church was revised by the Second Vatican Council, particularly in the Dogmatic Constitution Dei Verbum (1965) (hereinafter: DV). The statements contained in Dei Verbum are reproduced in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (KKK), especially in nos. 105-108 (more legible).

Doctrine of Inspiration in and after the Second Vatican Council

The explanations in Dei Verbum are kept brief. The new accentuations are to be seen against the background of the historical development of the doctrine of inspiration and the development of discussions within the Council.

Authorship of God

God is the “author” (Latin: auctor ) of the Holy Scriptures (DV 11). God is ascribed " a true influence on the hagiographers ". This is more than the influence by the general Providence ( Providence ). God is not referred to as "auctor litterarius" in the strict sense. DV 11 emphasizes the "share of hagiographers ... more" and recognizes their "differences and limitations":

“For the writing of the Holy Books, God has chosen people who, by using their own abilities and powers, were to serve Him as real authors, all and only that which He wanted to have written - effective in them and through them hand down"

"In the case of inspiration, a kind of illuminative imprinting of cognitive images in a miraculous and supranaturalistic sense is not to be thought of. It is the presence of the Holy Spirit that shapes man's natural ability to cognize in such a way that the witness of revelation in real, empirically tangible events and whose self-interpretation recognizes and writes down the Word of God expressed therein. "

The how of inspiration

The Second Vatican Council does not go into the exact how of inspiration and "dispenses with a psychologizing interpretation of inspiration". The classic representation is that of Thomas Aquinas in Summa theologica II-II, q. 171-174. According to this, God is the "auctor primarius", the hagiographer the "auctor secundarius". God has everything written down that he wants. The inspired authors are not passive tools, but act according to their nature: "namely in spirit and freedom according to the measure of his personal talent and in the horizon of his spiritual and cultural environment."

The controversy between the representatives of verbal inspiration and real inspiration is considered to be outdated or wrong. The Holy Spirit of the hagiographies did not "dictate" the text (verbal inspiration), nor was it "simply the result of a real inspiration that could ignore the wording of the Scriptures and mean a pre- or extra-linguistic sense. It is about the entire text in its full meaning, not a "thing behind the word". "

The inerrancy of Scripture

In Dei Verbum, the Second Vatican Council affirmed the inerrancy of the Holy Scriptures ( Inerranz ), but opened this claim to a differentiated consideration.

“Since everything that the inspired writers or hagiographers say is to be said of the Holy Spirit, it is to be confessed of the books of Scripture that they teach securely, faithfully and without error the truth that God for our salvation in wanted to have the scriptures recorded "

Here, too, the new accents to the previous ecclesiastical teaching can only be recognized in comparison to the 1962 draft for Dei Verbum. The stronger theses of a doctrine of verbal inspiration, the version of the doctrine of inerrancy in the previous biblical encyclicals and the "version of Inerranz in the form of 1962" are suppressed in favor of a holistic view. It is about God's purpose of salvation through all of Holy Scripture. The inerrancy exists only "insofar as the service of the word of salvation requires it". Any inaccuracies or inaccuracies in the sense of the profane sciences in statements with a mere "auxiliary function" therefore do not affect the inerrancy claimed in Dei verbum.

Biblical hermeneutics

The doctrine of inspiration is supplemented in Dei Verbum by an opening of the biblical exegesis: The (actual) "intention to make statements" (DV 12) of the hagiograph is, taking into account the literary genres , the doctrine of the multiple sense of writing , taking into account the conditions of "time and culture" (DV 12) of the hagiograph and taking into account the "three criteria": (1) observance of the "unity of the whole of Scripture" (DV 12; KKK no. 112), (2) the "living tradition of the universal church" (DV 12; KKK no 113) and (3) the analogy of faith (DV 12; KKK No. 114), d. H. the "connection [it] of the truths of faith with one another and in the overall plan of Revelation" ( CCC No. 114).

Historical development

Christian literature initially avoided the expression (θεόπνευστος (theopneustos) = (Latin: inspiratus )), which was used for a divine pneuma by seers, fortune tellers, oracles, poets etc. (see above) in order to avoid confusion and preferred the Expressions "prophecy" and "prophetic". The "technical term for the charisma of the biblical writers and scriptures only gradually became inspiration from the 17th century." This is how Thomas Aquinas (1224/5 - 1274) treated the inspiration "under the heading 'De Prophetia´".

Holy Scripture

In the Old Testament "a special influence of the Spirit of God" is predicated on people with difficult tasks ("judges", kings, artists, especially the prophets). Prophetic words are often introduced with the words "Thus speaks Yahweh". The prophets (especially Jeremias and Ezekiel ) speak of a "whispering" of Yahweh. The Old Testament speaks first of the inspiration of the words, of a script inspiration probably only in the apocryphal script 4 Ezra (around 100 AD).

In the New Testament , Christ himself describes Ps 110.1 EU as " spoken by (in) the Holy Spirit". As evidence for a conception of inspiration, among other things, 2 Tim 3:16 EU is cited: "Every scripture given by God [(θεόπνευστος (theopneustos = Latin. Inspiratus))] is also useful for instruction, for refutation, for improvement, for education in of justice; ... "

Patristic

In patristics , the interaction of God and man is dealt with in particular ( Chrysostom ; Augustine ; especially Origen ). The fact that God is the "auctor" (author) of the Holy Scriptures is not found until the 4th century. First with Ambrose , then more intensely with Augustine in the dispute with the Manichaeans , who viewed Satan as the author of the Old Testament .

scholasticism

Strongly influenced by Islamic ( Avicenna , Al Gazali , Averroes ) and Jewish authors ( Maimonides ), the “doctrine of prophecy” was systematically expanded in scholasticism , for example in the treatise De prophetia by Thomas Aquinas S. th. II-II, q. 171-174 (see above).

Tridentine Council

The Tridentine Council (1545–1563) dealt mainly with the question of canonicality and the use of the Holy Scriptures: the Old and New Testaments have God as their author ("Unus Deus sit auctor") and have been "dictated" by the Holy Spirit. ("a Spiritu Sancto dictatas") to apply. In retrospect, the phrase "dictated by the Holy Spirit" is felt to be unfortunate, as it could lead to "being able to categorize inspiration supranaturalistically and objectively". The "dictare" adopted from patristicism led to a controversy between representatives of a verbal inspiration (Banez, 1586) and a real inspiration (Lessius, 1587), which has been considered obsolete since Deiverbum (1965) at the latest .

First Vatican Council

The First Vatican Council (1869/70) repeated the teaching of the Council of Trent that the Holy Scriptures, inspired by the Holy Spirit , had God as author (DH 3006: "quod Spiritu Sancto inspirante conscripti Deum habent auctorem").

Encyclicals Providentissimus Deus and Divino afflante Spiritu

In the so-called Bible encyclicals of Pope Leo XIII. ( Providentissimus Deus (1893)) and by Pope Pius XII. ( Divino afflante Spiritu (1943)) the (pre-conciliar) inspiration doctrine of the Catholic Church is summarized and presented.

Islam

In the area of Islam there is the concept of Ilhām ( Arabic إلهام) a counterpart to inspiration. The term literally denotes a process of "letting it be swallowed" or "letting it be swallowed", but it is generally translated as "inspiration". In the Qur'an the term occurs only in one place, namely in Sura 91: 8 , where an oath is made by one who has "given the soul its sinfulness and its fear of God " ( alhamahā fuǧūrahā wa-taqwāhā ).

The concept only acquired greater importance in connection with the Sufi teaching of the friends of God ( auliyāʾ Allāh ). According to al-Hakīm at-Tirmidhī (d. 905-930), the gift of Ilhām is one of the seven signs by which friends of God can be recognized. It is widely believed that Ilhām is a separate type of revelation that is below prophetic revelation ( waḥy ). The difference between the two forms of divine communication is that in Ilhām God is only addressed individually to a single person, while in Revelation God is addressed to many or all people. The knowledge imparted through Ilhām is generally referred to as Ladun knowledge ( ʿilm ladunī ). The term is derived from Sura 18 : 65, where it says about Moses and his nameless companion: "And they found one of our (ie God's) servants .. to whom we had given knowledge of us ( min ladun-nā )". This nameless servant of God, who is endowed with special knowledge by God and who in the further course of the Qur'anic narrative tests Moses with several peculiar acts, is generally identified with al-Chidr .

The Persian Sufi Nadschm ad-Dīn al-Kubrā (d. 1220) equated Ilhām and Ladunian knowledge with an "incursion from God" ( ḫāṭir al-ḥaqq ) and describes them as something that neither mind, soul nor heart can oppose can. In his opinion, the inspiration is "clearest and closest to the experience" ( ašadd ẓuhūran wa-aqrab ilā ḏ-ḏauq ) if it has been received in a state of mental absence ( ġaiba ). In reality it is not a question of ideas, but of "pre-existing knowledge" ( ʿilm azalī ), which human spirits received from God at the time of creation. This knowledge could indeed be covered by the "darkness of existence" ( ẓalām al-wuǧūd ), but it could be made visible again by the fact that the person walking the mystical path purifies himself and removes himself from existence. When he then returns to existence, he will bring the inspirational knowledge with him. The process is comparable to writing that, after being covered by dust, becomes visible again through cleaning.

Others

- Inspiration is the title of an American film by George Foster Platt from 1915 with Audrey Munson in the lead role. It is considered to be the first American film to contain nude scenes.

- Inspiration Software Inc. is an American company for e-learning - Software that 60% of American school districts equips with their products.

See also

literature

- Abraham Avni: Inspiration in Plato and the Hebrew Prophets. In: Comparative Literature 20/1 (Winter 1968), pp. 55-63 ( online ).

- Eike Barmeyer: The Muses. A contribution to inspiration theory. Humanist Library 1/2, Fink, Munich 1968.

- A. Bea: Deus auctor sacrae scripturae. Origin and meaning of the formula. In: Angelicum 20 1943, pp. 16–31.

- Johannes Beumer: The Catholic doctrine of inspiration between Vatican I and II. Church documents in the light of theological discussion . Stuttgart Biblical Studies 20. Verlag Kathol. Bible work, Stuttgart 1966 (2nd edition 1967).

- EDF Brogan: inspiration. In: Alex Preminger, TVF Brogan (Ed.): The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1993, pp. 609f.

- Horst Bürkle, Josef Ernst, Helmut Gabel: Inspiration. In: LThK 5, pp. 533-541.

- James Tunstead Burtchaell: Catholic Theories of Biblical Inspiration since 1810. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1969 ( Google Books ).

- David Carpenter: Inspiration. In: Lindsay Jones (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Religion. 2nd Edition. Volume 7, Thomson Gale / Macmillan Reference, Detroit 2005, pp. 4509-4511.

- Helmut Gabel: The changing understanding of inspiration. Theological reorientation in the context of the Second Vatican Council. Grünewald, Mainz 1991.

- Wilfried Härle : Dogmatics . 2nd Edition. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016589-9 , pp. 119–123.

- Richard Hennig : The development of the feeling for nature. The essence of inspiration (= writings of the Society for Psychological Research. Volume 17). Barth, Leipzig 1912, pp. 89–160.

- G. Hornig, H. Rath: Inspiration. In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy 4, pp. 401–407.

- Ulrich HJ Körtner : The inspired reader. Central aspects of biblical hermeneutics. Goettingen 1994.

- J. Leipoldt: The early history of the doctrine of the divine inspiration. In: Journal of New Testament Science. 44 (1952/53), pp. 118-145. doi: 10.1515 / partly 1953.44.1.118 .

- Hermann Landolt, Todd Lawson (Eds.): Reason and inspiration in Islam. Tauris, New York 2004.

- Meinrad Limbeck: The Holy Scriptures. In: Max Seckler, Walter Kern u. a. (Ed.): Handbuch für Fundamentaltheologie, Volume 4. Francke, Tübingen / Basel 2000, pp. 37-64, esp. 44ff.

- Christoph Markschies , Ernst Osterkamp (ed.): Vademecum of the means of inspiration. [As part of the 2011/2012 annual theme of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities "ArteFacts - knowledge is art, art is knowledge".] Wallstein, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-8353-1231-9 ( table of contents , abstract of contents ).

- Gert Mattenklott (Ed.): Aesthetic experience under the sign of the dissolution of boundaries of the arts. Epistemic, aesthetic and religious forms of experience in comparison. Meiner, Hamburg 2004.

- Penelope Murray: Poetic Inspiration in Early Greece. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 101, 1981, pp. 87-100 ( online ).

- M. Nachmansohn: To explain the consciousness experiences that arise through inspiration. In: Archive for the whole of psychology 36 (1917), pp. 255–280.

- R. Peppermüller: Inspiration. In: Lexikon des Mittelalters 5, p. 450.

- Karl Rahner : About font inspiration. Quaestiones disputatae 1st 2nd edition. Herder, Freiburg i.Br. 1959.

- Maria Ruvoldt: The Italian Renaissance imagery of inspiration. Metaphors of sex, sleep, and dreams. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004, ISBN 0-521-82160-6 .

- Eckhard Schnabel : Inspiration and Revelation. The doctrine of the origin and nature of the Bible . Brockhaus, Wuppertal 1986 (2nd edition 1997), ISBN 3-417-29519-X .

- Christoph J. Steppich: Numine afflatur. The poet's inspiration in Renaissance thought. Gratia 30. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 3-447-04531-0 .

- EN Tigerstedt: Furor Poeticus. ( Memento of April 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.7 MB) Poetic Inspiration in Greek Literature before Democritus and Plato. In: Journal of the History of Ideas. 31/2 1970, pp. 163-178.

- Josef van Ess : Theology and Society in the 2nd and 3rd Century Hijra , Volume 4, de Gruyter, Berlin 1997, 613ff et passim (esp. Sv ilham, ta'yīd, waḥy).

- Josef van Ess: Verbal inspiration? Language and Revelation in Classical Islamic Theology. In: Stefan Wild (Ed.): The Quran as Text. Brill, Leiden 1996, pp. 177-194.

- Arent Jan Wensinck , Andrew Rippin: WAḤY. In: Encyclopaedia of Islam . 2nd edition, Volume 11. 2002, pp. 53-56.

- Jonathan Whitlock: Scripture and Inspiration. Studies on the idea of inspired script and inspired scriptural interpretation in ancient Judaism and in the Pauline letters (= scientific monographs on the Old and New Testaments, 98). Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2002.

- Steffen Köhler: inspiration and faith in words. JH Röll, Dettelbach 2004, ISBN 3-89754-226-9 .

Web links

- Ernstpeter Maurer: Inspiration. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Otto Pautz: Muhammad's doctrine of revelation . Sources examined, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1898.

- Biblical Interpretation Basics: Inspirational Teaching

Individual evidence

- ↑ Democritus, fragment B18 in: Diels / Kranz: The fragments of the pre-Socratics .

- ↑ E.g. De divinatione I, 18f.67; II, 57 u. ö .; De natura deorum II, 66; Pro Archia 8.

- ^ Keyword “Inspiration” in: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy. Volume 4, Basel 1976, Col. 404-406.

- ↑ Dei Verbum, 13

- ^ Keyword “Inspiration” in: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy. Volume 4, Basel 1976, Col. 401-403.

- ↑ E.g. Jeremiah 36, 1-2

- ↑ O. Weber: II. Inspiration of St. Scripture, dogma history. In: Religion in Past and Present Volume 3 1959, pp. 775–779, 778.

- ↑ Cf. Gerhard Ludwig Müller : Catholic Dogmatics: for the study and practice of theology. 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg i. Br./ Basel / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-451-23334-7 , p. 62: "New version of the theory of inspiration"

- ↑ a b II Inspiration and Truth of the Holy Scriptures . In: Catechism of the Catholic Church . Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ↑ Alois Grillmeier : Commentary on the third chapter of Dei Verbum . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 13 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, Sp. (P.) 528 ff .

- ↑ Alois Grillmeier : Commentary on the third chapter of Dei Verbum . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 13 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, Sp. (P.) 545 .

- ↑ Alois Grillmeier : Commentary on the third chapter of Dei Verbum . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 13 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, Sp. (P.) 545 fn. 7 .

- ↑ Alois Grillmeier : Commentary on the third chapter of Dei Verbum . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 13 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, Sp. (P.) 545 .

- ^ Gerhard Ludwig Müller : Catholic dogmatics: for study and practice of theology. 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg i. Br./ Basel / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-451-23334-7 , p. 61.

- ↑ Alois Grillmeier : Commentary on the third chapter of Dei Verbum . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 13 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, Sp. (P.) 545 .

- ^ So Gerhard Ludwig Müller : Catholic dogmatics: for study and practice of theology. 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg i. Br./ Basel / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-451-23334-7 , p. 61; A. Bea critical: Inspiration. II. History of the cath. Teaching . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 5 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1960, Sp. 704 . : "the role of the author's individuality is less taken into account"

- ^ So Gerhard Ludwig Müller : Catholic dogmatics: for study and practice of theology. 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg i. Br./ Basel / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-451-23334-7 , p. 61 f.

- ↑ Cf. Gerhard Ludwig Müller : Catholic Dogmatics: for the study and practice of theology. 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg i. Br./ Basel / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-451-23334-7 , p. 62.

- ^ So Peter Hofmann : Catholic dogmatics. Schöningh, Paderborn 2008 (UTB basics; 3098), ISBN 978-3-506-76572-7 , p. 145.

- ↑ Alois Grillmeier : Commentary on the third chapter of Dei Verbum . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 13 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, Sp. (P.) 549 .

- ↑ Alois Grillmeier : Commentary on the third chapter of Dei Verbum . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 13 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, Sp. (P.) 550 .

- ↑ Alois Grillmeier : Commentary on the third chapter of Dei Verbum . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 13 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, Sp. (P.) 550 .

- ↑ Comprehensible overview in KKK vatican.va No. 115–118

- ↑ KKK vatican.va No. 111

- ↑ III The Holy Spirit is the interpreter of Scripture . In: Catechism of the Catholic Church . Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ↑ Augustin Bea : Inspiration. I. Name and meaning . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 5 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1960, Sp. 703 .

- ^ Gerhard Ludwig Müller : Catholic dogmatics: for study and practice of theology. - 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg i. Br./ Basel / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-451-23334-7 , p. 61.

- ↑ Augustin Bea : Inspiration. II. History of the cath. Teaching . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 5 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1960, Sp. 703 .

- ↑ Augustin Bea : Inspiration. II. History of the cath. Teaching . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 5 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1960, Sp. 703 f. mwN .

- ↑ Mk 12, 36: "For David himself, filled with the Holy Spirit, said: The Lord said to my Lord: Sit at my right hand and I will put your enemies under your feet." (Standard translation)

- ^ So Gerhard Ludwig Müller : Catholic dogmatics: for study and practice of theology. 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg i. Br./ Basel / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-451-23334-7 , p. 61.

- ↑ Augustin Bea : Inspiration. II. History of the cath. Teaching . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 5 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1960, Sp. 703 (704) .

- ↑ Augustin Bea : Inspiration. II. History of the cath. Teaching . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 5 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1960, Sp. 703 (704) .

- ↑ Denzinger Enchiridion catho.org

- ↑ Denzinger Enchiridion catho.org

- ^ Gerhard Ludwig Müller : Catholic dogmatics: for study and practice of theology. 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg i. Br./ Basel / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-451-23334-7 , p. 61.

- ↑ Augustin Bea : Inspiration. II. History of the cath. Teaching . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 5 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1960, Sp. 703 (704) .

- ↑ Denzinger Enchiridion catho.org

- ↑ See the representation in Augustin Bea : Inspiration. III. The cath. Lesson from inspiration . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 5 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1960, Sp. 705-708 . (As of 1960) and the (after) conciliar evaluation by Alois Grillmeier, among others : Commentary on the third chapter of Dei Verbum . In: Josef Höfer , Karl Rahner (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 2nd Edition. tape 13 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, Sp. (P.) 528-551 .

- ↑ See DB Macdonald: Art. "Ilhām" in The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Volume III, pp. 1119b-1120a.

- ↑ Cf. Bernd Radtke: Drei Schriften des Theosophen von Tirmiḏ. Part I: the Arabic texts, Beirut-Stuttgart 1992, p. 57.

- ↑ Cf. Patrick Franke : Encounter with Khidr. Source studies on the imaginary in traditional Islam. Beirut / Stuttgart 2000, pp. 198-200.

- ↑ Cf. Fritz Meier : Die Fawāʾiḥ al-ǧamāl wa-fawātiḥ al-ǧalāl of Naǧm ad-Dīn al-Kubrā, a presentation of mystical experiences in Islam from around AD 1200. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1957, p. 99f, 127, arab. Part No. 25.