First Vatican Council

|

First Vatican Council December 8, 1869 - October 20, 1870 |

|

| Accepted by | |

| Convened by | Pope Pius IX |

| Bureau | |

| Attendees | 744 clerics |

| subjects |

Rationalism , fideism , liberalism , materialism ; Inspiration of writing ; Pope's infallibility |

| Documents | |

|---|---|

The First Vatican Council (also briefly Vatican I and I. Vatican or Vatican I and Vatican I ) controlled by the Roman Catholic Church as the 20th Ecumenical Council is considered, began on 8. December 1869 . In the summer of 1870 it announced a teaching document on the Catholic faith, the papal jurisdiction primacy and raised the doctrine of the infallibility of the Pope "in final decisions in doctrines of faith and morals" to a dogma ; the resistance to these resolutions resulted in theold Catholic Church . At the meeting break occurred after the declaration of war by France to Prussia for German-Prussian War , and then the Kingdom of Italy the Papal States occupied. The council was not resumed and was adjourned on October 20, 1870 for an indefinite period.

story

The first Vatican Council was held on June 29, 1868 on the occasion of the 1800th anniversary of the martyrdom of Peter and Paul by Pope Pius IX. convened. The aim of the council should be the defense against modern errors and the contemporary adaptation of church legislation.

prehistory

Pius IX had devoted his pontificate since the uprisings in Italy in 1848 above all to the struggle against the Risorgimento and liberalism . To this end, he had already published the encyclical Quanta Cura before the council , which contained the syllabus errorum (about the errors of time to be rejected) as an appendix . The First Vatican Council should also dedicate itself to this struggle. To this end, from December 6, 1864, first curiae cardinals, then also bishops of the Latin and later also of the oriental rite, were secretly requested to write appropriate reports. On the basis of these reports, from the summer of 1867 five factual commissions, 2/3 of which were members of the Curia and 1/3 of foreigners, worked on the schemes that were to be presented to the council for discussion. The final formulation of the schemes was the responsibility of a central commission, which also had to decide on the rules of procedure used.

The announcement of the council aggravated the dispute in the Catholic world (especially in France which had lasted since around 1830) between state- affiliated Catholics and the ultramontanes or the followers of the Syllabus Errorum. Since it quickly became clear that the council would point in the direction of the ultramontanes, these contradictions subsequently intensified. A book by the Catholic theologian Ignaz von Döllinger , which he published under the pseudonym "Janus" and which in the interests of German national identity opposed the primacy and infallibility of the Pope, brought particular sharpness into the discussion . It was only through the controversy that this sparked that attention was drawn to this point, which until then had hardly been included in the original program. Many governments also feared that the council would again lay claim to secular violence on the basis of the syllabus, which rejected a politically motivated separation of religion and state.

opening

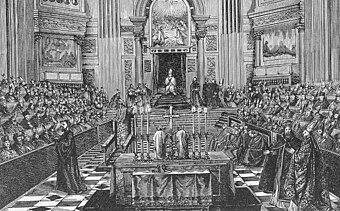

After the opening of the council on December 8, 1869, the deliberations of the council fathers took place in 89 general congregations under the presidency of five Italian cardinals . According to a contemporary engraving , Pius IX. as a council father at the opening a white choir shirt , a mozetta , a stole and the tiara on his head over his cassock . The Pope himself only presided at the four solemn sessions (also at the Second Vatican Council ). The north (right) cross arm of St. Peter's Basilica functioned as the council hall .

Attendees

At the beginning 774 prelates took part in the council. A total of 1089 would have been eligible to participate. Later, an average of 700 prelates took part in the meetings, towards the end there were only 600. A third of them came from non-European countries, among them 61 from the United Eastern Churches, 121 from America, 41 from Asia, 18 from Oceania and nine from Africa. Most of them had a European education, which is why the council was in principle dominated by European interests. Germany and Austria, for example, sent 77 representatives, the representatives of the Italians (35%) and French (17%) together made up more than half of all participants. Nevertheless, this was the council with the largest number of participants to date.

course

From the beginning, the debate about papal infallibility dominated the Council and divided the Council Fathers into two camps. Bishops in particular called for such a dogma to be adopted. The 88 opponents of the declaration of infallibility made up 20%. But they included almost the entire German-Austrian episcopate , Swiss bishops and part of the French bishops' college.

The majority of the Council succeeded in excluding opponents of the dogma of infallibility (such as Ignaz von Döllinger ) from the most important commission for this question, the Commission Deputatio Fidei. The opponents of the dogma mostly did not doubt its truth, but rather the expediency of the definition out of political consideration.

On December 28, 1869, the examination of the first submission of a dogmatic constitution against the error of modern rationalism began . It failed the deliberations and was referred back by the Commission Presidents to the relevant Commission for a new submission. The deliberations in the council hall proved to be difficult because the speaking time was not limited and consequently the details were lost. This was handled differently at the Second Vatican Council . In March 1870 the constitution was up for resubmission and was adopted on April 24, 1870 and proclaimed by the Pope as Constitution Dei Filius .

By this time the majority of the Council had long since pooled their strengths to put the question of papal infallibility on the agenda. At the end of December 1869 a corresponding petition signed by 450 Council Fathers had been sent to the Pope. The council minority then tried to dissuade the majority from their plans by means of theological brochures and treatises. She even broke the secret of the Council and started a press campaign against the project.

However, on March 1, 1870, the Pope decided that an addition ( Caput addendum de Romani Pontificis Infallibilitate ) should be added to the scheme “De Ecclesia” (about the Church ), which should deal with the infallibility of Peter's successor. After several steps by the council majority, he decided on April 27, 1870 that this addition should become a constitution that should be discussed before the council plenum. On May 13th, deliberations on the constitution began, dealing with the expediency of the definition, theological questions and practical questions about advantages and disadvantages. The text was often improved, but not to everyone's satisfaction. In a vote on July 13, 1870, the constitution received 88 votes against. The final vote was to take place on July 18, 1870 in the presence of the Pope at the fourth public session. In order not to have to vote against the document there, around 60 bishops left the city beforehand. At the session, 533 voted for the definition of the primacy of jurisdiction and papal infallibility, only 2 voted against. The opponents soon submitted. This constitution ( De ecclesia Christi ) with its controversial fourth chapter ( De Romani Pontificis infallibili magisterio ) states:

“As the successor of Peter, representative of Christ and supreme head of the Church, the Pope exercises full, ordinary, direct episcopal power over the Church as a whole and over the individual dioceses. This extends to matters of faith and morals as well as discipline and church leadership [...] "

The discussion on this question did not end with the vote, but it was now dogma whose absolute binding force had to be adhered to. The Old Catholics , who did not want to recognize the dogma, split off . After this session the council was supposed to continue, but the Pope had granted a leave of absence until November 11, 1870, which all but 100 bishops made use of. The De Sede Episcopali vacante scheme (on the Sedis vacancy ) was still being negotiated in two general congregations .

But after France declared war on Prussia and the previous protective power of the Papal State withdrew its troops from there, the Italians took the opportunity to annex the Papal State on September 20, 1870 . A month later the Pope postponed the council “sine die” (“without an appointment”, that is for an indefinite period of time) - it was not resumed.

Council documents

- Dei Filius , 1870 (Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith)

- Pastor Aeternus , 1870 (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church of Christ)

Reactions

The proclamation of the primacy of jurisdiction and the infallibility of the Pope led to negative reactions in many places. Austria, for example, terminated a concordat concluded with the Curia in 1855 , citing the clausula rebus sic stantibus . The church was split off and the Old Catholic Church and the Christian Catholic Church of Switzerland were founded .

literature

- Bernward Schmidt : Small history of the first Vatican council . Herder, Freiburg a. a. 2019, ISBN 978-3-451-38430-1 .

- Peter Neuner : The long shadow of Vatican I. How the Council is still blocking the Church today . Herder, Freiburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-451-38440-0 .

- Julia Knop / Michael Seewald (eds.): The First Vatican Council. An interim balance 150 years later WBG, Darmstadt, 2019, ISBN 978-3-534-27136-8 .

- The Vatican Council , its history portrayed from within in Bishop Ullathorn's letters, translated by Dom Cuthbert Butler and expanded by Hugo Lang , Josef Kösel & Friedrich Pustet, Munich 1933.

- Klaus Schatz : Vaticanum I: 1869–1870 . (Council history series A.) Schöningh, Paderborn a. a. 1992ff. (Part 1: Before the opening , 1992, ISBN 3-506-74693-6 ; Part 2: From the opening to the constitution “Dei Filius” , 1993, ISBN 3-506-74694-4 ; Part 3: Discussion of infallibility and reception , 1994, ISBN 3-506-74695-2 ).

- Viktor Conzemius: «Pourquoi l'autorité pontificale at-elle été définie précisément en 1870? », Concilium , n ° 64 (1971).

- J. Gadille: «Vatican I, concile incomplet? », Le Deuxième concile du Vatican , Actes du colloque de l'École française de Rome, Rome 1989, pp. 33-45.

- H. Rondet: Vatican I, le concile de Pie IX. La preparation, les méthodes de travail, les schémas restés en suspens , Lethielleux, Paris 1961.

- Gustave Thils: Primauté et infaillibilité du Pontife romain à Vatican I et autres études d'ecclésiologie , Presses de l'Université de Louvain, Louvain 1989, ISBN 90-6186-328-7 .

Web links

- Publications by and about the First Vatican Council in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ See belief 388 on pages 234 and 235 in: Josef Neuner SJ and Heinrich Roos SJ: The faith of the church in the documents of the doctrinal proclamation. Fourth improved edition, published by Karl Rahner SJ - Regensburg: Verlag Friedrich Pustet, 1954. Imprimatur June 27, 1949.

- ↑ cf. Klaus Schatz: Vatican Councils A. I Vatican . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 10 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2001, Sp. 556-561 . , 556