Aeolian harp

The aeolian harp or aeolian harp (also called ghost , wind or weather harp ) is a stringed instrument , the strings of which are brought to resonance and thus to sound through the action of a stream of air . Its name is derived from Aiolos , Latin Aeolus, the ruler of the winds in Greek mythology . According to their design, the aeolian or wind harp almost always belongs to the family of zither instruments , not the harp .

The aeolian harp is often seen as a symbol for the poet . This connection is based on the concept of afflatus .

functionality

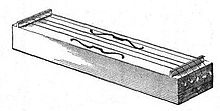

An aeolian harp consists of a long, narrow resonance box (usually with sound holes) on which any number of low- density strings (for example natural gut or nylon strings ) are stretched over two bridges. As a rule, the strings are of the same length, tuned to the same keynote , but of different thicknesses and may have different surface properties. The wind blows over the strings and creates the so-called Aeolian tones through air vortices (see also Kármán vortex street ). This causes the strings to vibrate, which in turn produce a sound. Depending on the wind speed, melody sequences or even chords arise when the overtones of the various strings of the instrument are stimulated. The sound has a magical effect, as, depending on the strength of the wind, the chords swell from pianissimo to forte and then decay again. The air flow and thus the effect of a wind harp can be increased by means of appropriate tail units above the strings.

history

Aeolian harps were already known in antiquity. King David is said to have hung his instrument, the kinnor , over his bed so that at night he could listen to the sound of the strings excited by the wind. The Middle Ages, where the sound of the Aeolian harp was often associated with magic , also tells of harps that sound through the draft . Saint Dunstan of Canterbury (10th century) is said to have improved their mode of action. Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) gave the first theoretical explanations of the Aeolian harp in Musurgia universalis (1650) and Phonurgia nova (1673). It was then forgotten and was rediscovered by English poets ( James Thomson , William Collins , Tobias Smollett and Alexander Pope ) in the mid-18th century . In the late 18th and 19th centuries, the instrument flourished again and was further developed in terms of instrument construction by the German music theorist Heinrich Christoph Koch and the Austrian piano maker Ignaz Josef Pleyel, who lived in Paris . As a symbol, it found its way into literary and musical works ( Novalis , Jean Paul , ETA Hoffmann , Herder , Justinus Kerner , Joseph von Eichendorff ; Beethoven , Berlioz , Liszt , Reger , Schreker , Cowell , Henze and others).

In his 1976 album Dis , the Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek used recordings of an aeolian harp set up by a fjord.

Giant weather harp

In 1789 Georg Christoph Lichtenberg described a 15-string, almost 100 meter long and on one side almost 50 meter high weather harp in a garden in Basel in the Göttingen pocket calendar under the heading New inventions, physical and other oddities . The strings were about two, three and four millimeters thick and about five centimeters apart. Since the intensity of the sounds depended on the time of day and the direction of the strings and the weather harp worked with iron strings but not with brass strings, the cause of the sound generation was seen not only in the movement of the air, but also all sorts of electrical ones , magnetic and thermal effects considered.

It was not until 1825 that Ernst Florens Friedrich Chladni mentioned in the journal Annalen der Physik that the cause of the sound formation in this giant weather harp was probably to be found exclusively in the wind, as it was mainly blowing in a preferred direction in the garden in question.

Since iron has a modulus of elasticity that is about twice as high as brass, it can be assumed that the brass strings could not be tensioned enough to make them sound because of the insufficient load capacity that can be achieved.

Modifications

In connection with a keyboard, an aeolian harp is also called an anemochord . Another stringed instrument stimulated by the wind is the Gora bow played by the Khoisan in South Africa . The East Asian kite musical bows are also stimulated by the wind .

Similar to the wind harp is the wind harmonica, a sound tube with reeds that are excited by the wind. These instruments were built in Markneukirchen in the 1920s / 1930s and experienced a brief renaissance around 1990. A wind harmonica, manufactured by the Guriema company, has been installed on the roof of the Markneukirchen Musical Instrument Museum since 1997.

Well-known wind harps

The currently largest wind harp in Europe is in the knight's hall of the Old Castle in Baden-Baden . The harp, which was set up in 1999, has a total height of 4.1 meters and 120 strings, it was developed and built by the musician and harp maker Rüdiger Oppermann based in the region . The nylon strings are stimulated by the draft to produce the basic notes C and G. As early as 1851 (?) To 1920 there was a small wind harp in the knight's hall in the old castle. In the musical instrument collection of the Württembergisches Landesmuseum Stuttgart there is a historically particularly remarkable reconstruction of an Aeolian harp with vestibule, made by the concert harp maker Rainer Thurau (Wiesbaden 1991).

Poetry

Eduard Mörike was taken by the sound of an Aeolian harp so that it it with the poem on a Äolsharfe has set in 1837 a monument that both Johannes Brahms and by Hugo Wolf and Emil Kauffmann in the form of a song with piano accompaniment has been set to music:

|

|

Goethe had his poem Aeolian harps in 1822 . Written a conversation , and the lyrical contribution of the English romantic Samuel Taylor Coleridge on the subject of aeolian harp had already appeared in 1796 .

In Goethe's Faust 1 , reference is made to the instrument in the fourth (last) stanza of attribution.

- And I am seized by a long weaned longing

- After that quiet, serious spirit realm,

- It now floats in indefinite tones

- My lisping song, like the Aeolian harp,

- A shiver seizes me, tear follows tears,

- The strict heart, it feels mild and soft;

- I see what I have in the distance

- And what has disappeared becomes a reality for me.

At the beginning of Faust 2 , Ariel's singing is "accompanied by Aeolian harps" according to the stage direction.

See also

Web links

- youtube.com Sound sample of an aeolian harp

literature

in alphabetical order

- Jan Brauers: From the Aeolian harp to the digital player. 2000 years of mechanical music - 100 years of records . Klinkhardt and Biermann, Munich 1984, 279 pp.

- Ernst Florens Friedrich Chladni : Weather Harp . In: Annalen für Physik 79 (1825), pp. 471–473

- Johann Friedrich Hugo von Dalberg : The Aeolian harp . Erfurt 1801.

- Kilian Jost: "That harmony is deeply rooted in nature (...) especially shows us the Aeolian harp". A forgotten acoustic equipment of the early landscape garden . In: Die Gartenkunst 26 (2/2014), pp. 201–208.

- Jean-Georges Kastner: La harpe d'éole et la musique cosmique - Etudes sur les Rapports des Phénomènes sonores de la Nature avec la science et l'art - suivies de "Stephen" or la Harpe d'Eole, grand monologue lyrique avec choeurs . Brandus / Renouard, Paris 1856.

- Athanasius Kircher : Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna consoni et dissoni in X. libros digesta 2. Rom 1650, pp. 352-354.

- Athanasius Kircher: New Hall and Thon art, or mechanical Gehaim connections of art and nature, stiffened by voice and hall science, what meaning in common the voice, Thons, Hall and sound nature, property, strength and miracle effect ... in the same way as the speech and hearing instruments, machines and art works ... are manufactured. Translated by Agatho Carione (di Tobias Nisslen) . Schultes, Nördlingen 1684, p. 104 ff.

- Athanasius Kircher: Phonurgia Nova sive Conjugium Mechanico-physicum Artis & Naturae paranympha phonosophia Concinnatum . Rudolphum Dreherr, Campidonae [Kempten i. Allgäu] 1673, pp. 143-145.

- Heinrich Christoph Koch : Musical Lexicon . Frankfurt am Main 1802.

- A. Langen: On the symbol of the Aeolian harp in German poetry . In: Festschrift J. Müller-Blattau. Kassel 1966.

- Georg Christoph Lichtenberg : Description of the giant weather harp under new inventions, physical and other oddities . In: Göttinger Taschenkalender 1789, pp. 129–134.

- Ilse Maltzahn: The Aeolian Harp . In: Die Gartenkunst 2 (2/1990), pp. 258–269.

- Mins Minssen, Georg Krieger, a. a .: Aeolian harps. The wind as a musician . Erwin Bochinsky, Frankfurt 1997. ISBN 3-923639-14-7

- Walter Windisch-Laube: A muse born in the air, mysterious string playing. On the meaning of the Aeolian harp in texts and tones since the 18th century . Are Verlag, Mainz 2004. ISBN 978-3-924522-18-6

- Walter Windisch-Laube: A Magic Lantern Of Sound? The Aeolian Harp between Cheap Showmanship and Spiritual Mystery, shown here as a Catalyst within the History of Music . In: Mildorf, Seeber, Windisch (Ed.): Magic, Science, Technology, and Literature . Berlin 2006, pp. 249-266.

- Aeolian Harp . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 1 : A-Androphagi . London 1910, p. 258 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- windharfe.m3u - Live stream of a wind harp at the University of Ulm (Musisches Zentrum)

- Secret of the Aeolian Harp

- The Aeols Door Harp

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe : Aeolian harps . poem

Individual evidence

- ↑ Aeolian harp. In: Music in the past and present .

- ↑ Heidrun Eichler, Gert Stadtlander (Red.): Musikinstrumenten-Museum Markneukirchen . Saxon State Office for Museums (Hr.), Berlin / Munich 2000 (Saxon Museums, Vol. 9). ISBN 3-422-03077-8 .

- ↑ Samuel Taylor Coleridge - The Æolian Harp of August 20, 1795 ( Memento of November 16, 2007 in the Internet Archive )