Kinnor

Kinnor , also kînôr ( Hebrew כִּנּוֹר, masculine plural kinnorim , feminine plural kinnoroth ), is an old Israelite , pre-Islamic plucked instrument that is compared or equated with the Greek kithara and counted among the lyres (synonymous with yoke sounds). The widespread attribution as David's harp by the biblical King David does not take into account the different form of a lyre.

etymology

Kinnor appears 42 times in the Old Testament . However, the name for a musical instrument and different forms of lyres existed long before that. The oldest known text on music comes from Ebla and dates back to around 2500 BC. Dated. The large clay tablet contains a lexical list of musical instruments and other musical terms in cuneiform , including the Semitic name ki-na-ru . Similar smaller panels from the 26th century BC. Are known from the Mesopotamian places Šuruppak (Fara) and Abū Ṣalābīḫ . Variations of the word can be found on other clay tablets from Ebla up to around 2300 BC. To read. A lyre called kinaru (Pl. Kinaratim ) was found on clay tablets from the 18th century BC. BC, which were discovered in the palace archives of Mari . In the 14./13. Century BC The instrument seems to have been worshiped as sacred in Ugarit . The consonant spelling knr occurs six times in Ugaritic texts, as a deity and as a stringed instrument. The identity of the names refers to the connection between the sacrificial cult and the music of an instrument whose tone was mistaken for the voice of God. The name Kinyras of the mythical king of Cyprus goes back to the same root knr .

The word kinnor is also found in the names of Phoenician and Canaanite gods, rulers and place names: Kinyras, Kinnyras, Kuthar, Kinnaras or Kinnaret (the Sea of Galilee ), where kinnor was also derived from Sanskrit kinnara ("to sound"). Kunar , the name for “lotus wood”, goes back to the Egyptian 18th – 19th centuries . Dynasty back when the Semitic foreign word knwrw referred to a lyre. The lyre is mentioned in Arabic texts from the early Islamic period - handed down from the 9th century - as al-kinnāra or kinnīra , but was hardly widespread.

Finds

According to seals found in ancient Israel at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC A lyre in use, which had a rectangular body with symmetrically extending yoke arms. At the end of the 8th century a design became popular with six or more parallel strings running between asymmetrical arms. Whether the images are kinnorim or other lyres can be disputed in individual cases. Lyres are rarely depicted in connection with wind instruments. A seal of unknown origin, made by Nahman Avigad in the 7th century BC. According to the Hebrew inscription, it was the property of the king's daughter Maadanah, but is now believed by a majority of researchers to be a modern forgery due to numerous inconsistencies (see also: Seal of the Maadana ).

Kinnorim are also depicted on coins from the Bar Kochba uprising .

Kinnor in the Biblical and Arabic tradition

The lyre is mentioned in Gen 4,21 EU , among others . There the Old Testament Lamech descends in the fifth generation from Cain . Lamech's son with his wife Zilla was called Tubal-Cain , and according to biblical and Arabic tradition he is considered the first blacksmith . Another son named Jubal is said to have invented the kinnor . Naama was the daughter of the two. The scholar Gregorius Bar-Hebraeus wrote about her in the 13th century that she had taught the other women to sing, dance and make themselves beautiful. These are the special abilities of the female descendants of Cain from the nomadic tribe of the Kenites . Wine was drunk in their camps, music was played with flutes, lyres and drums, and people danced happily. The descendants of Seth , the third son of Adam and Eve, are quite different . Sitting on the holy mountain, they led a godly life for themselves and lamented the fornication and shamelessness that prevailed among the Kenites. Their seductive women are said to have even managed to lure Seth's sons by playing on the kinnor . The story can be found as “seduction of the devil” (Talbīs Iblīs ) in the Islamic tradition. There Zilla (Arabic Ḍilāl ) is considered by al-Mas'udi (around 895–957) as the inventor of the stringed instruments.

The feminine form qaina (Pl. Qiyān ) belongs to Cain , corresponding to the Arabic qain from the consonant root qyn . From pre-Islamic times through the Islamic Middle Ages to the 20th century, Qaina was a singing girl who sang, made music and hard-drinking in front of the guests at parties, but was not allowed to be prudish. The descendants of Cain represent a mythological connection between blacksmithing and music .

Overall, in the Old Testament and post-biblical traditions , the kinnor proves to be the symbol of professional musicians and song poets who performed at feasts, feasts and magical rituals. At the same time, the kinnor had a ritual function in the temple service and the transfer of the Israelite ark .

Kinnor in the Jewish tradition

Levites played the kinnor during the musical performance of psalms in the Jerusalem temple . In the Bible the kinnor is mentioned 22 times together with the nevel , another, probably somewhat larger stringed instrument. The nevel is said to have had twelve thick gut strings and was used from the end of the 6th century BC. Used in the Jerusalem temple. The kinnor owned by different biblical to the Mishnah six or ten, in any case, less and thinner (from Vogeldärmen existing) strings than the nevel . The musicians struck the kinnor with an opening pick and the nevel with their hands. In the Jewish musical tradition, both were instruments of the Levites who were employed as official temple musicians.

According to the Jewish historian of the 1st century AD, Flavius Josephus , the instrument played in the temple was made from electrons, which probably meant an alloy of gold and silver. On the other hand, according to Book 2 of the Chronicle , King Solomon had musical instruments made from fragrant sandalwood , which should come from the legendary land of Ophir . Maybe the metal was used for decoration. According to the Mishnah, at least twelve singers and twelve instrumentalists appeared at the festive events, nine of whom had to be kinnor and two nevel players. At even bigger parties there were six nevel and any other kinnor players. A thousand years later, Josephus gives impressive numbers for the musicians: According to this, 200,000 singers, 40,000 kinnor , 40,000 sistras and 200,000 trumpets and their musicians should have fit into the temple .

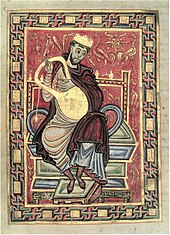

The name David Harp goes back to a legend that King David , who never with another attribute as the kinnor is displayed in your hands, such an instrument as a kind of wind harp had fastened on his bed. Every time at midnight the north wind began to blow and stroked the strings, whereupon the king woke to a wondrous sound to study the Torah until dawn .

literature

- Joachim Braun: Biblical musical instruments. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Material part Volume 1, Bärenreiter, Kassel and Metzler, Stuttgart 1994, Sp. 1503–1537, here Sp. 1516f

Individual evidence

- ^ Thomas Staubli: Music in Biblical Times . Ed .: Bible + Orient Museum. Friborg 2007, p. 20 .

- ^ Richard Dumbrill: MS 2340 IC200710: 12. ( Memento from May 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Icobase

- ↑ Lyres. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Part 5, 1996, Col. 1016

- ^ Pieter W. Van Der Horst, Karel Van Der Toorn, Bob Becking: Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Brill, Leiden 1999, p. 488.

- ↑ Friedrich Nork : Complete Hebrew-Chaldean-Rabbinical Dictionary on the Old Testament, the Thargumim, Midrashim and the Talmud. Grimma 1842, p. 325

- ↑ Joachim Braun: The music culture of old Israel / Palestine: Studies on archaeological, written and comparative sources. (Publications of the Max Planck Institute for History). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, p. 39f, ISBN 978-3-525-53664-3

- ↑ Christian Poche: Kinnārāt. In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. 3, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 165

- ^ Hans Hickmann: The music of the Arabic-Islamic area. In: Bertold Spuler (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Orientalistik . 1. Dept. The Near and Middle East. Supplementary Volume IV. Oriental Music. EJ Brill, Leiden / Cologne 1970, p. 64

- ↑ Joachim Braun, p. 127

- ↑ Philip J. King: Amos, Hosea, Micah. An Archaeological Commentary. Westminster Press, London 1988, p. 155, ISBN 978-0-664-24077-6

- ↑ Hans Engel : The position of the musician in the Arab-Islamic area. Verlag for systematic musicology, Bonn 1987, pp. 234–236

- ↑ Joachim Braun, p. 40

- ↑ Joachim Braun, pp. 40, 45

- ↑ August Wilhelm Ambros : History of Music. First volume. First book: The beginnings of music. FEC Leuckart, Breslau 1862, p. 208 f.

- ↑ Amnon Shiloah: Jewish Musical Traditions. (Jewish Folklore & Anthropology) Wayne State University Press, Detroit 1995, pp. 43, 63 f., ISBN 978-0-8143-2235-2