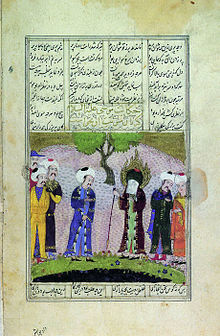

Moses in Islam

Moses (s) ( Arabic موسى, DMG Mūsā ) is considered an important prophet in Islam and is the most frequently named person in the Koran . In the Islamic exegesis tradition he plays an essential role as the leader of the Israelites , as a recipient of the Torah and as a forerunner and pioneer of the Prophet Mohammed . In the traditional collections , his role during the Ascension of Muhammad is also a particular theme. His honorary title Kalīm Allaah ('the one to whom God speaks') indicates that, in contrast to other prophets , God did not speak to him through mediators, but directly.

Moses in the Koran

Moses is mentioned a total of 137 times in the Book of Revelation, more often than any other Koranic figure. His confrontation with the pharaoh and the magicians is particularly prominent . Allusions to the covenant on Mount Sinai in connection with the disobedience of the Banī ʾIsrāʾīl are also frequent. The episode about Moses and the “ servant of God ”, who appears as a teacher to the prophet, is completely without any biblical parallel or intertext .

First years of life, escape to Midian and mission

The birth of Moses, his first years of life and his flight to Midian are mainly discussed in Sura 28 and again in the context of his mission in Sura 20 . According to this, Moses was prepared for his calling in the sacred valley of wanuwan; At the burning bush, God had asked him to take off his sandals, then warned him of the Last Judgment and made him aware of the stick in his hand, which would turn into a snake if he threw it to the ground. At the request of Moses, who feared that he would not be up to his task alone, God had assigned his brother Aaron as a helper who was to give him strength and strength. The brief reference to his salvation shortly after his birth and to his renewed salvation from the impending death penalty serves in this context primarily to draw his attention to God's past benefits and thus to encourage him.

The themes of his abandonment as an infant, which was supposed to protect him from the murderous stalkings of the violent Pharaoh, who then raised him as his own son under the watchful eyes of his biological sister, the slaying of an encroaching Egyptian overseer at his hand and the forgiveness that God gives him thanks to his repentance, his escape and the time in Midian are mentioned in the first verses of Sura 28. In Midian, after eight or ten years of work as a shepherd in addition to his wife Zippora ( Arabic صفورة, DMG Ṣaffūra ) and his iconic staff also a flock of sheep, all symbols of fertility. Finally, in verses 33–35, God reassures fearful Moses that he will protect him from harm and from his opponents.

Confrontation with the Pharaoh and Exodus

The confrontation between Moses and Aaron on the one hand and the Pharaoh and his sorcerers on the other is one of the most frequently referenced narrative episodes in the Koran and is repeatedly taken up as a motif, especially in Sura 7 : 103-126, Sura 20 : 59-78 and Sura 26 : 36-51. Moses lets the sorcerers go first and is at first impressed and intimidated by their idea of turning their staffs into snakes, but is in turn encouraged by God, who tells him not to worry. In Sura 43 : 52 the Pharaoh expresses himself contemptuously about the difficulties of Moses in making himself understood, only to be humiliated in the end.

The staff of Moses turns into a snake that devours the other snakes, exposing the magic of the Egyptian wizards as a mere illusion. In contrast to the Pharaoh, whose heart remains obstinate, the magicians then prostrate themselves in awe to God and are executed by the vengeful ruler for it.

The plagues sent against Egypt are only marginally described in sura 7: 133–35; the biblical killing of the firstborn is omitted, rather the remaining six plagues are embedded in a series of "nine signs" (Sura 27:12), in addition to the transformation of the staff into a serpent, the shining white hand and the division of the sea Moses through God. Despite his defeat, however, the Pharaoh refuses to release the Israelites from bondage and continues to pursue them, for which he is finally judged in the Red Sea .

Moses on Mount Sinai

The Israelites' wandering in the desert is of only marginal interest in the Koran; apart from the miracle of water and manna mentioned in sura 2 : 57-60 , which is mainly performed to show the ingratitude of the children of Israel against God's benevolence, only the meeting of God and Moses on Mount Sinai and the episode with the golden calf , but all the more detailed.

In the course of his dialogue with God, Moses asks to see God's face ( Sura 7 : 143). God then asks his prophet to look at the mountain: If he remained steadfast in his place, his request would be fulfilled; but God turns the mountain to dust, whereupon Moses falls and passes out. When he comes to, he lets go of his wish. In Sura 4 : 164, however, a separate reference is made to the fact that God "really" and directly spoke to Moses:وَكَلَّمَ ٱللَّهُ مُوسَىٰ تَكۡلِيمً / wa-kallama llāhu mūsā taklīman / 'and God really spoke to Moses', which sets Moses apart from the other prophetic messengers. The epithet of the Prophet can also be traced back to this incident.

Moses and the Prophet of God

In Sura 18 : 60–82 an incident is described which has absolutely no biblical equivalent. It is about his journey to "the place where the two great waters meet", to which he sets off in the company of his servant. Already on the way the first miraculous occurrence occurs: The fish that they had with them to eat takes its way into the water and swims up and away. Eventually they meet a servant of God whom Moses joins in order to learn from him, whose fear that Moses will not be able to muster enough patience is repeatedly fulfilled, each time commented laconically with:أَلَمۡ أَقُلۡ إِنَّكَ لَن تَسۡتَطِيعَ مَعِیَ صَبۡرًۭا / ʾA-lam ʾaqul ʾinnaka lan tastaṭīʿa maʿiya ṣabran / 'Didn't I say that you will not be able to hold out with me?' In the later interpretation, the mysterious figure that Moses encounters in this episode is equated with the mythical figure al-Chidr . The source of the story is traced back to the Alexander novel .

Moses in the exegesis tradition and in popular legend

The Islamic exegesis tradition supplements the story of Moses with numerous other episodes and explicitly relates them to the path of life and the prophetic mission of Muhammad. In particular, there is a targeted attempt to link the stories of Moses and Jacob , which is only hinted at in the Koran. For example, at-Tabarī , citing as-Suddī , adds that Moses lifted a rock out of the well in Midian and thus made it possible for the two shepherds, whom he had come to the aid of, to water their animals. The tradition shows considerable similarities to the story of Jacob ( Gen 29 EU ).

In particular, the staff of Moses was and is the subject of many legends: It originally came from Paradise, was in the meantime in the possession of various prophets such as Ādam and Ibrāhīm , and Moses first had to fight over it with his father-in-law - a dispute that only came through one Engel had been decided in favor of Moses. According to aṯ-Ṯaʿlabī , it glows in the dark, makes it rain in the drought and, when planted in the ground, becomes a fruit-bearing tree. He defends his owner from attackers. According to another legend, the stick of Moses was found in the Ka'ba after the Ottomans conquered Mecca .

A place between Jerusalem and Jericho is traditionally regarded as the place of the Prophet's burial place. In 1269 Baibars I had a shrine built there, which was expanded in later centuries and became a place of pilgrimage. In April 1920, during the celebrations in honor of the Prophet, the so-called Nabi Musa riots broke out in the old city of Jerusalem . In Sunni Islam is on Ashura of the Red Sea as part of the crossing Exodus thought.

literature

- Bernhard Heller: Mūsā . In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam . Second Edition, Vol. 7, 1993, pp. 638-639.

- Uri Rubin: Between Bible and Qurʾān: The Children of Israel and the Islamic Self-Image . Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam 17. Darwin, Princeton, 1999.

- C. Sirat: Un midras juif en habit musulman: La vision de moïse sur le mont Sinaï. In: Revue de l'Histoire des Religions 168, 1965, pp. 15-28.

- Brannon Wheeler: Moses in the Quran and Islamic Exegesis . Quranic Studies Series. Routledge, London, 2002.

Individual evidence

- ^ Adel Theodor Khoury : The Koran. Translated and commented by Adel Theodor Khoury. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2007, ISBN 978-3-579-08023-9 , p. 304.