Sabina Spielrein

Sabina Spielrein Naftulowna ( Russian Сабина Нафтуловна Шпильрейн; born October 26 . Jul / 7. November 1885 greg. In Rostov-on-Don , † 12. August 1942 ibid) was a Russian Jewish doctor and psychoanalyst . She was a patient and student of Carl Gustav Jung and the first woman to receive a doctorate in psychoanalytic work.

Life

Sabina Spielrein was the daughter of the wealthy Russian-Jewish businessman Nikolai Arkadjewitsch Spielrein and his wife Eva Markovna Lyublinskaja, a dentist and daughter of a Hasidic rabbi . The mother had studied dentistry, but mainly devoted herself to her five children. Spielrein attended the girls' grammar school in Rostov and graduated from it in 1904.

In 1904 she was admitted to the psychiatric university clinic “ Burghölzli ” in Zurich with the diagnosis of “ hysteria ” and treated by the local senior physician Carl Gustav Jung , among others . From 1905 to about 1907 Spielrein was a patient of Jung, who treated her psychoanalytically and corresponded with Sigmund Freud on her account . Jung mentioned the "20 year old Russian student" for the first time in his third letter to Freud from Zurich in October 1906 and asked him for his opinion. Again he mentioned the "hysterical patient" who now wanted a child from him in mid-1907, and then again in 1909, because she had caused him "a wild scandal". Shortly afterwards Spielrein wrote to Freud directly, which C. G. Jung informed him. This correspondence possibly led Freud to the dictum of training analysis , according to which every analyst must first submit himself to an analysis before treating patients himself.

In the spring of 1905, Sabina Spielrein began studying medicine at the University of Zurich . From 1908 onwards, Spielrein and Jung developed a friendship and, according to the diary entries and letters, an intimate relationship in addition to the contact made during their studies. It is not known for sure whether there was sexual contact.

In the correspondence between Jung and Freud from 1907 to 1909, in which Jung indicated a sexual desire in play without admitting and explaining his role in it, Freud first mentioned the " countertransference " and his experience with it. The intense relationship with Jung culminated in Spielrein's idea of naming a child “Siegfried”. The psychoanalyst Peter Loewenberg described this as a violation of professional ethics (jeopardized his position at the Burghölzli and led to his rupture with Bleuler and his departure from the University of Zurich) .

In 1911 received his doctorate Spielrein was the first woman with a decidedly psychoanalytic theme in Zurich Dr. med. with the work On the Psychological Content of a Case of Schizophrenia. Her dissertation was published in the Yearbook of Psychoanalysis edited by Jung. Spielrein stayed in Munich in 1911 and in Vienna for nine months , where he also got to know Sigmund Freud personally. She took part in the legendary " Wednesday Society " and was accepted into the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association .

On June 14, 1912, she married the Russian-Jewish doctor Pavel Naumowitsch Scheftel in Rostov-on-Don. Their daughter Irma Renata was born in Berlin on December 17, 1913 . At the beginning of the First World War , Pawel Scheftel and Sabina Spielrein managed to escape from Germany to Switzerland . Pavel Scheftel left his wife and child to join his Kiev regiment. Sabina Spielrein stayed with her little daughter in the west. She lived in Lausanne from 1915 to 1921 and continued to publish in psychoanalytic journals. In 1921 she was Jean Piaget's psychoanalyst in Geneva for eight months .

In 1923 she returned with her daughter to Russia, which has since become Soviet . She became a member of the Russian Psychoanalytic Association and worked at the State Psychoanalytic Institute in Moscow. Spielrein returned to her native Rostov-on-Don in 1924 and lived with her husband Pawel Scheftel again. On June 18, 1926, the couple had a second daughter, Eva.

In 1929 psychoanalysis was banned as "idealistic" and "subjectivistic" in the Soviet Union. Spielrein then worked as a pedologist . In 1937, pedology, d. H. testing children to determine their school career is prohibited. In order to be able to work at all, she was given part-time work as a doctor. However, she continued to write and publish articles in Western psychoanalytic journals.

After the city of Rostov was captured for the second time on July 24, 1942 as part of the German attack on the Soviet Union , the approximately 25,000 Jews living in Rostov had to assemble in a school building on August 11 and 12, 1942 and then became Smijowskaya Balka (snake gorge) driven. There they - including the 56-year-old Sabina Spielrein and her 29- and 16-year-old daughters Irma Renata and Eva - were shot dead by a part of Einsatzgruppe D.

Sabina Spielrein's brothers Isaak , Jan and Emil Spielrein disappeared between 1935 and 1937 and were shot by the NKVD in 1937/38 . They were in 1956 on the XX. CPSU party congress under Nikita Khrushchev rehabilitated.

plant

In her psychoanalytic publications, Sabina Spielrein dealt with, among other things, schizophrenic psychoses and dreams and wrote several authoritative essays on child psychology . Spielrein is considered a pioneer in the psychoanalysis of children and the analysis of child development of the psyche . She was the first to develop the thesis that the sex drive consists of two opposing components, which was adopted by Freud. In her work The Destruction as a Cause of Becoming from 1912, Spielrein described the death wish as part of the libido , which inspired Freud to the idea of the death drive . Spielrein left diaries and correspondence with Sigmund Freud and Carl Gustav Jung, which have since been published and are considered important documents from the early phase of psychoanalysis.

Honors

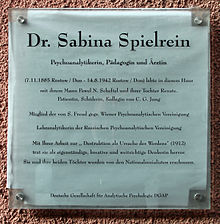

A memorial plaque was put up by the "German Society for Analytical Psychology" on the Berlin house of Sabina Spielrein at Thomasiusstrasse 2 in Berlin-Moabit .

Fonts (selection)

- Destruction as the cause of becoming. In: Yearbook for psychoanalytic and psychopathological research, IV. Vol., First half. Leipzig / Vienna 1912, pp. 465–503. ( Online archive )

- All writings. Psychosozial-Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-89806-880-2 .

- All writings. With a foreword by Ludger Lütkehaus . Psychosozial-Verlag, Giessen 2002, ISBN 3-89806-146-9 .

- Aldo Carotenuto (Ed.), Sabina Spielrein: Diary of a Secret Symmetry - Sabina Spielrein between Young and Freud. With a foreword by Johannes Cremerius. Kore, Freiburg im Breisgau 1986, ISBN 3-926023-01-5 . (Original Italian: Diario di una segreta simmetria - Sabina Spielrein tra Jung e Freud. Astrolabio - Ubaldini, Rome 1980.)

- Sabina Spielrein: diary and letters. The woman between Jung and Freud. Edited by Traute Hensch, act. And exp. New edition. Psychosozial-Verlag, Giessen 2003, ISBN 3-89806-184-1 .

swell

- Andreas Schwab: Spielrein, Sabina. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Karen Hall: Sabina Spielrein. 1885 - 1942 , Jewish Women 'Archive (English)

- Sabina Nikolajevna Spielrein In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung , 2001

literature

- Alexander Etkind : Eros of the Impossible. The history of psychoanalysis in Russia. Kiepenheuer, Leipzig 1996, ISBN 3-378-01006-1 .

- Renate Höfer: The psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein. 1st chapter. Christel Göttert, Rüsselsheim 2000, ISBN 3-922499-41-4 .

- John Kerr : A very dangerous method. Freud, Jung and Sabina Spielrein. From the American by Christa Broermann and Ursel Schäfer. Kindler, Munich 1994.

- Zvi Lothane : In defense of Sabina Spielrein. In: International forum of psychoanalysis, 5 (1996), pp. 203-217. In defense of Sabina Spielrein

- Wolfgang Martynkewicz : Sabina Spielrein and Carl Gustav Jung. A case history. Rowohlt, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-87134-287-4 .

- Sabine Richebächer: Spielrein, Sabina Nikolajewna. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , p. 691 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Sabine Richebächer: Are you and you with the devil and do you want to shy away from the flame? Sabina Spielrein and C. G. Jung: a repressed scandal of early psychoanalysis. In: Thomas spokesman: The unconscious in Zurich. Literature and depth psychology around 1900. NZZ Verlag, Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-85823-834-1 , pp. 147–187.

- Sabine Richebächer: Sabina Spielrein - an almost cruel love for science. Biography. Dörlemann Verlag, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-908777-14-3 .

- Sabine Richebächer: "I long to get together with all of you ..." - A letter from Sabina Spielrein-Scheftel (Rostow-on-Don) to Max Eitingon on August 24, 1927. In: Luzifer-Amor - Zeitschrift zur Geschichte der Psychoanalysis. Volume 21, issue 42nd edition discord, Tübingen 2008, ISSN 0933-3347 .

- Christoph Weismüller: "Siegfried lives, lives, lives!" The "Siegfried" with Sabina Spielrein, Carl Gustav Jung and Richard Wagner. Der Frauen Held, or: Sabina Spielrein's drafts for a reality of the female gender - notated by a man, Philosophy of the Media IV. Peras Verlag, Düsseldorf 2019, ISBN 978-3-935193-35-1 .

Sabine Spielrein in fiction

- Bärbel Reetz: The Russian patient. Novel. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-458-17290-4 .

Movies

- My name was Sabina Spielrein. Documentary, Germany 2002. Director: Elisabeth Márton.

- Prendimi l'anima. Feature film, Italy / France / Great Britain 2003. Director: Roberto Faenza. Film about the relationship between Sabina Spielrein and Carl Gustav Jung. With Emilia Fox as Sabina Spielrein and Iain Glen as C. G. Jung.

- A dark desire . Feature film, Canada / Great Britain / Germany 2011. Director: David Cronenberg . With Keira Knightley as Sabina Spielrein, Michael Fassbender as Carl Gustav Jung and Viggo Mortensen as Sigmund Freud .

Web links

- Literature by and about Sabina Spielrein in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Sabina Spielrein in the German Digital Library

- Sabina Spielrein in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Sabina Spielrein. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- Erhard Taverna: Small laboratory explosions. In: Schweizerische Ärztezeitung , 2002, 83 (38): pp. 1996–1997 (PDF; 114 kB)

- Sabina Nikolajevna Spielrein. Russian Jew, doctor, pioneer of psychoanalysis. Biographical article. In Neue Zürcher Zeitung, July 28, 2001

- Sabina Spielrein in the Central Database of the Names of the Holocaust Victims

- Heike Oldenburg, Jessica Thönnisse, Burkhart Brückner: Biography of Sabina Nikolajewna Spielrein In: Biographical Archive of Psychiatry (BIAPSY) .

Individual evidence

- ^ Sigmund Freud, CG Jung: Correspondence. Edited by William McGuire, Wolfgang Sauerländer. S. Fischer, Frankfurt 1974. ISBN 3-10-022733-6 . Pp. 7, 79 and 229.

- ^ Sigmund Freud, CG Jung: Correspondence. Edited by William McGuire, Wolfgang Sauerländer. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 1974, ISBN 3-10-022733-6 , p. 255.

- ^ Peter Loewenberg: The Creation of A Scientific Community: The Burghölzli, 1902-1914. Fantasy and Reality in History. Oxford University Press, New York 1995, p. 76.

- ↑ Sabina Spielrein: About the psychological content of a case of schizophrenia (Dementia Praecox). Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the high medical faculty of the University of Zurich. Dissertation at the Medical University of Zurich, 1911.

- ^ Sigmund Freud, CG Jung: Correspondence. Edited by William McGuire, Wolfgang Sauerländer. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 1974, ISBN 3-10-022733-6 , p. 493.

- ↑ My name was Sabina Spielrein. LIFE AND WORKS. sabinaspielrein.com, accessed on August 29, 2014 .

- ^ Karen Hall: Sabina Spielrein. 1885-1942. Jewish Women 'archives (English)

- ^ New edition 1986, edited by Gerd Kimmerle in Edition Diskord, Tübingen.

- ^ Rainer Zuch: The return of the displaced. Review of Sabina Spielrein: Complete Writings. At literaturkritik.de , November 2004, accessed on September 3, 2011.

- ^ Publisher information on the new edition ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) by Sabina Spielrein: Diary and Letters. The woman between Jung and Freud. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ Press comments on Renate Höfer: The psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein. From the publisher, accessed on September 3, 2011.

- ^ Rolf Löchel: CG Jung's women's state. Review of Wolfgang Martynkewicz: Sabina Spielrein and Carl Gustav Jung. A case history. At literaturkritik.de, October 2001, accessed on September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Publishing information, with excerpt and press reviews. To the biography of Sabina Spielrein - "An almost cruel love for science" by Sabine Richebächer. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ Official film website. Accessed September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Reviews: 1 ( Friday No. 48, November 21, 2003) / 2 (Brigitte Häring, myBasel.ch) / 3 (Anne Kraume in taz , November 17, 2003) / 4 (Sabine Hensel at Cinema Schweizer Filmjahrbuch). Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ Official film website ( Memento from January 20, 2003 in the Internet Archive ). (In the Internet Archive .)

- ^ Film report from Venice. ( Memento of the original from March 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Tages-Anzeiger of September 3, 2011, accessed 2011.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Spielrein, Sabina |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Spielrein, Sabina Naftulowna (full name); Spielrein, Sabina Nikolajewna (full name, alternative patronymic) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian-Jewish psychoanalyst |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 7, 1885 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Rostov on Don |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 12, 1942 |

| Place of death | Rostov on Don |