Synchronicity

As synchronicity ( ancient Greek σύν syn , German 'with, together' and χρόνος chronos 'time'), the psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung described temporally correlating events that are not linked by a causal relationship (which are therefore a causal), but as each other connected, perceived and interpreted in relation to one another.

theory

The term synchronicity

Synchronicity is an internal event (a lively, stirring idea, a dream, a vision or an emotion) and an external, physical event, which is a (physically) manifested reflection of the internal (mental) state or its equivalent . In order to actually define the double event as synchronicity, it is essential that the inner happening chronologically before or exactly at the same time ("synchronously") with the outer event. Otherwise it could be assumed that the inner phenomenon reacts to the externally perceived previous event (which again would allow a quasi-causal explanation).

The synchronistic principle

Jung uses the term he introduced to describe both the phenomenon and the hypothetical principle behind it. He used the term “synchronistic principle” publicly for the first time in 1930 in his obituary for Richard Wilhelm : “The science of the I Ching is not based on the causal principle, but on a principle that has not yet been named - because we do not exist - that I tentatively call called the synchronistic principle . "

Differentiation from seriality

Jung strictly distinguishes synchronicity (unusually methodical for him) from seriality, as examined above all by Paul Kammerer in his book “The Law of Series” (1919). He regards these as curious - merely amusing - coincidences that lack the creatively transforming potential of synchronicity. According to Jung, this potential comes from the activation of an archetype that is focused in the individual psyche for a certain period of time in order to be developed there. Jung describes this process as the individuation process .

Symbolic power

Synchronicity creates meaning through its symbolic power, the physical component of coincidence becomes the bearer of the symbol thanks to its intension (specific correspondence) and its limited extension (low frequency ). This allows it to be recognized as a resonance and response to the (chronologically preceding) emotion. It is also considered important to analyze the meaning of a synchronicity event and to derive consequences for one's own behavior. Numerology (the symbolic meaning of numbers) often plays an essential role in the "linking of meaning" of a synchronicity.

The Quaternio

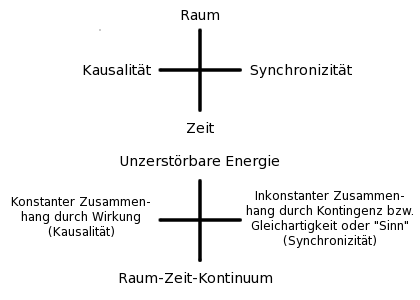

Jung illustrates the principle of synchronicity in a quaternio, a cross made up of two polar complementary pairs of terms that complement each other diametrically and are therefore to be understood in a similar way to the pair of terms wave / particle in the transition from classical physics to quantum theory.

“Indestructible energy” is used here to describe the quantity that remains constant in all physical processes, including the conversion of energy into mass and vice versa. Its appearance, which is constantly changing through all the physical processes, is understood as a kind of dance that unfolds as an evolution on the stage of the space-time continuum.

Jung does not deny that each of the events involved stands in its own causal chain. Therefore, the synchronicity does not question the causal principle , but extends it linearly to the purely acausal opposite pole: In their development, things are meaningfully related to one another and “arranged as they are” (acausal orderedness).

Collaboration between Jung and Wolfgang Pauli

Jung discussed this topic intensively with the physicist Wolfgang Pauli during his long-term correspondence (1932–1958, published in 1992 by CA Meier, a Zurich psychiatrist and long-time friend of the physicist and the depth psychologist). The term synchronicity appears for the first time in the Pauli / Jung correspondence in 1948 (letter [35]). Pauli may have known it as early as 1934, since Jung used it in a letter to his physicist colleague Pascual Jordan . Pauli knew Jordan from his time in Hamburg and continued to communicate with him orally and in writing. Jung publicly mentioned the term synchronicity in 1950 in the preface to the English translation of the I Ching . Finally, in 1952, together with Pauli, he published the book Nature Declaration and Psyche , in which Jung comprehensively deals with the subject under the title Synchronicity as a principle of acausal relationships .

Examples

The best-known example from Jung's practice:

“At a crucial moment in her treatment, a young patient had a dream in which she received a golden scarab as a gift. I sat with my back against the closed window while she was telling me the dream. Suddenly I heard a noise behind me, as if something was knocking softly on the window. I turned around and saw a flying insect bump into the window from the outside. I opened the window and caught the animal in flight. It was the closest analogy to a golden scarab that our latitudes were able to raise, namely a scarab beetle (scarab beetle), Cetonia aurata , the common rose beetle, which had evidently felt induced, contrary to its usual habits, to break into a dark room at this very moment . "

The physicist Wolfgang Pauli himself believed in the anecdotally transmitted Pauli effect , according to which experimental equipment failed or even broke spontaneously in his presence. When Pauli was admitted to the Rotkreuzspital in Zurich in 1958, he was deeply shocked to find that he was in room 137 of all places. He linked the number with the value of the fine structure constant , which is almost exactly 1/137, and saw this as a bad sign. Pauli died there after an unsuccessful operation on December 15, 1958, whereby it must be said that (regardless of the room number) the prospects for a cure for malignant pancreatic cancer , as in the case of Pauli, are extremely poor.

literature

- CG Jung: Synchronicity, acausality and occultism. dtv, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-423-35174-8 . (Paperback edition in eleven volumes, Volume 5)

- CG Jung: Collected Works. , Vol. 8 Walter, Olten (CH) 1971, p. 475ff. (§ 816ff.), Synchronicity as a principle of acausal relationships. First published In: CG Jung, Wolfgang Pauli : Nature Declaration and Psyche. Rascher Verlag, Zurich 1952; Pauli's contribution was The Influence of Archetypal Concepts on the Formation of Scientific Theories in Kepler .

- Elisabeth Mardorf: It can't be a coincidence! Amazing events and mysterious coincidences in our lives . Schirner Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-89767-630-5 .

- Carl A. Meier (eds.): Wolfgang Pauli and CG Jung. An exchange of letters from 1932 to 1958. Springer, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-540-54663-4 . (English translation: Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0-415-12078-0 )

- CG Jung: Basic work. Volume 2: Archetype and Unconscious. Walter, Olten 1990, ISBN 3-530-40782-8 .

- F. David Peat: Synchronicity. The hidden order. Scherz-Verlag, 1989, ISBN 3-502-67499-X .

- Jean Shinoda Bolen: Tao of Psychology. Sensible coincidences. Sphinx Medien Verlag, 1989, ISBN 3-85914-228-3 .

Web links

- Synchronicity research German / English

- https://www.psychovision.ch/sinnvolle-zufalle/

- Global Consciousness Project - Registering Coherence and Resonance (and Synchronicity) in the World