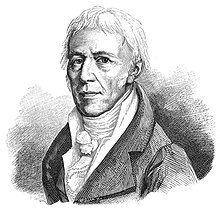

Paul Kammerer

Paul Kammerer (born August 17, 1880 in Vienna , † September 23, 1926 in Puchberg am Schneeberg ) was an Austrian biologist .

He became famous through experiments with midwife toads , with which he wanted to prove the inheritance of acquired traits . He committed suicide on suspicion of having falsified his experimental results. Whether or not Kammerer falsified his results could not ultimately be ascertained. In his suicide note, he recently continued to deny alleged fakes.

Life

Paul Kammerer was the son of the factory owner Carl Kammerer in Vienna and his wife Sofie and had three brothers. At an early age he demonstrated an unusual skill in dealing with animals, he converted his parents' apartment into a terrarium . After leaving school, he studied zoology at the University of Vienna from 1899 . In addition, he took lessons in counterpoint at the Conservatory of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna from 1900 to 1901 with the renowned music teacher Robert Fuchs , whose apprenticeship had also been taught by Gustav Mahler and Alexander Zemlinsky . As an alleged “half-Jew”, he was exposed to anti-Semitic attacks by biologists such as August Weismann , Fritz Lenz and Ludwig Plate and, according to his own information, by colleagues .

Biological research institute

In 1902, Kammerer became an adjunct to Hans Leo Przibram at the Biological Research Institute (the former “ Vivarium ”) in the Vienna Prater , where he was entrusted with setting up terrariums and aquariums . He began to breed amphibians with the most modern facilities at the time . Soon he was noticed by his skill in animal breeding and was able to carry out his first independent experiments on the inheritance of acquired traits ( Lamarckism ). Przibram later reported:

“When setting up the biological research institute, we were looking for an employee who would set up the terrariums and aquariums and make the institute comfortable for the small animals. Drawn to him by a newspaper article by Kammerer about his animal care, I went to see him and found an enthusiastic and skilled employee. In him was a facility for musical activity and a large part of artistic nature as well as the ability to observe nature very closely and, in particular, a love for all living creatures that I have never seen in anyone else. Here was the fulcrum of his whole being. In particular, he set up the exemplary care for amphibians and reptiles, which is so important for biological experiments. I have hardly known anyone who would have met all the requirements for it like him. However, this was not necessarily an advantage, because the main value of the experimental method is precisely that the same results can be achieved over and over again under the same test conditions and can be confirmed during re-testing. If the follow-up examiner does not succeed in keeping the animals alive for as long or for as many generations as the first observer, how should a follow-up check lead to a confirmation and thus certainty of the findings? "

Soon it was said that Kammerer had extraordinary abilities in experimental handling, for example with frogs , and his experiments with the midwife toad - although described in detail - could not be repeated later by anyone. In the years up to 1908 Kammerer wrote 130 articles, contributions and research reports in the research institute in the Prater.

In 1904 Kammerer did his doctorate at the University of Vienna and in 1906 married the baroness Felicitas Maria Theodora von Wiedersperg , who gave birth to a daughter in 1907 who was baptized Lacerta (= lizard ).

After various photo and collecting trips, he got a job as a biology teacher at the Cottage Lyzeum in Vienna-Döbling (1906–1912) and finally completed his habilitation in 1910 at the University of Vienna.

Inheritance of acquired traits

Through his work in the “Vivarium”, Kammerer soon became a well-known biologist. He devoted himself to a series of experiments that were supposed to prove the heritability of acquired traits , and called it “Evidence for the inheritance of acquired traits through systematic breeding”. Many of his attempts were based on artificially modified habitats of amphibians.

In a first series of experiments, he used two species of salamander, the black alpine salamander Salamandra atra and the spotted fire salamander Salamandra salamandra , and forced them to breed in the opposite habitat. This enabled him to develop properties of the Alpine salamander on the fire salamander and vice versa. When he succeeded in demonstrating the same inversions in their descendants, the scientific sensation was perfect.

He had apparently succeeded in proving that living beings that have acquired organic properties in the course of their existence in order to cope better with their living conditions, could also pass these on to future generations. According to Kammerer's discovery, it was not Darwin's theory and the random principle of evolution that were correct, but rather the hypothesis of his predecessor Lamarck , who had claimed in his laws of inheritance that species would develop according to the principle of systematic and logical transformation.

This conclusion had great ideological significance. It would have given a scientific basis to the political endeavor to breed happy future generations. Racist ideologues claimed that parentage was fate. Paul Kammerer countered this: "We are not slaves of the past, but foremen of the future."

Kammerer also transferred this idea to people - in a lecture he said: “By bringing up children well, we give them more than a short profit from their own lives; an extract of it goes to where the human being is truly immortal - in that wonderful substance from which grandchildren and great-grandchildren arise in uninterrupted succession. "

His criticism of eugenics brought him ridicule in the then ideologically highly charged discourse on the life sciences. Kammerer got caught between the fronts of an expert dispute which was fought with great severity.

In a next experimental set-up, which was to last over eleven years, he bred the black, yellow-spotted Salamandra maculosa alternately on yellow and black soil, with the color of their spots increasing or decreasing according to the substrate. Again this development continued with the offspring.

Kammerer also found out that the blind cave olm Proteus , who lives in caves and only has rudimentary eyes that are hidden deep under the skin, develops pigmentation spots but no vision when raised under normal daylight, but large eyes and perfect vision under red light can develop.

In Viennese society

Kammerer belonged to the best Viennese society , he was friends with many artists, and took care of his institute from an international as interdisciplinary network that the conductor Bruno Walter , the sociologist Rudolf Gold Scheid , the composer Alban Berg and Franz Schreker , the philosopher Ludwig Erik Tesar as also included Albert Einstein . He had well-known affairs with the dancer Grete Wiesenthal , the painter Anna Walt (who also portrayed him in 1924) and with Alma Mahler . In addition, he was involved in freemasonry .

The following account of Kammerer has come down to us from the biologist Richard Goldschmidt :

“He had a brilliant, if somewhat theatrical, delivery style. He was also well-built and elegantly dressed, so he looked quite impressive with his dark artist's mane and fine facial features. (...) He was an extremely sensitive, decadent, but highly gifted man who sat down at night after a long day in the laboratory and composed symphonies. In fact, he wasn't actually a scientist at all, but what the Germans call an 'aquarist', an 'amateur' (sic!) Who breeds small animals. He was extraordinarily skilled at this, and I think the results he has presented on the direct influence of the environment are by and large correct. "

Kammerer played the piano excellently , wrote music reviews and composed songs himself , which were published by the renowned Simrock publishing house. He was a great admirer of the music of Gustav Mahler , from whose death in 1911 he was so shaken that he wrote to the widow Alma Mahler on October 31:

“It is incomprehensible how one can love someone without sexual undercurrent, without relatives and actually even without outwardly expressed friendship ties as I love Mahler. Because that was and is not just admiration, enthusiasm for art and person, that is love! "

Alma, to whom he later dedicated the booklet On Acquisition and Inheritance of Musical Talent , belonged to Kammerer to the "rare type of brilliant Viennese woman". He worshiped her excessively and repeatedly threatened to shoot himself at Gustav Mahler's grave if she did not reciprocate his love. He wrote about her:

“In being with her, the potential energy collects, which is subsequently released as kinetic energy. There are people with whom I meet every day and who work the other way round: the potential energy is used up and afterwards, when I need it, there is too little kinetic energy. "

Alma describes Paul Kammerer's admiration:

“When I got up from an armchair, he would kneel down and smell and caress the chair where I was sitting. He didn’t care whether there were strangers in the room or not. There was nothing to keep him from such extravagances, of which he had an abundance. "

In November 1911 he suggested Alma Mahler become his assistant, and for a while she worked for him in the biological research institute in Vienna's Prater . She later recalled:

“Now he gave me a mnemonic attempt to work with praying mantises. He wanted to find out whether these animals lose their memory by molting or whether this act is just a superficial skin reaction. For that purpose I should teach them a habit. It failed in that there was nothing really to teach these critters. I had to feed them down in the cage, because a priori they always eat up high and in the light. The cage was blacked out below. They could not be made to give up their beautiful habit of Kammerer zu Liebe. "

Alma had to feed the test animals with mealworms, “and I was dreaded by this huge box full of wriggling worms. He saw it, took a handful and put the creatures in his mouth. He ate them with a loud smack. "( Alma Mahler-Werfel : The shimmering way , see above)

Alma Mahler later suggested that there could have been irregularities in Kammerer's experiments in the Prater laboratory: "He wished the results of his research so ardently that he could unconsciously deviate from the truth."

The law of the series

In 1919 Kammerer published the book The Law of the Series. A doctrine of the repetitions in life and world events, the title of which has become proverbial. In it he developed the causality-independent principle of seriality on the basis of years of observation of inexplicable coincidences that came from personal experience (many of them with numbers), from the stories told by friends or from newspapers. Kammerer presented a collection of such case studies before his remarks, for example: “On May 17, 1917 we were invited to Schrekers. On the way there, I buy my wife chocolate sweets at the candy stand in front of the Hütteldorf-Hacking train station. - Schreker plays for us from his new opera The Drawn , whose main female role is CARLOTTA. When we come home, we empty the bag with the sweets; one of them bears the (...) inscription CARLOTTA. "

He called these separately appearing but matching numbers, names and situations as cyclical processes of different order and power and designed his own terminology to classify the series . He claimed that a series was the regular repetition of the same or similar events that could not have been linked by the same cause (his biographer Arthur Koestler later spoke of "meaningful coincidences" ). With this, Kammerer wanted to prove that a universal law of nature manifests itself in so-called "coincidences" that works independently of known physical causal principles. He wrote:

“We have accepted that the sum of the facts excludes every 'chance' or makes the chance such a rule that its concept appears to be suspended. This brings us to our central thought: At the same time as causality, an acausal principle is active in the universe. This principle acts selectively on form and function in order to bring together related configurations in space and time; and it has to do with kinship and similarity. "

With his book, Kammerer founded the theory of seriality, which is important for the history of parapsychology , and his principle is one of the most important precursors of the idea of synchronicity in CG Jung and Wolfgang Pauli , which had previously appeared in Camille Flammarion . In his book Synchronicity, Acausality and Occultism, Jung refers to the publication by Kammerer. Even Albert Einstein spoke positively ( "Original and not at all absurd"), and Sigmund Freud was in his essay The Uncanny on Kammerer one: "An ingenious naturalist (Paul Kammerer) has taken recently attempted incidents subordinate of this kind to certain laws whereby the impression of the uncanny would have to be canceled. I don't dare to decide whether he succeeded. "

The midwife toad

Kammerer exposed midwifery toads , which normally mate on land, to high temperatures in order to lure them into the cool water. In order not to slip off the female at the amplexus in the water, the males are said to have developed rut or adhesive calluses on the inside of the fingers - a feature that this frog in particular does not normally have. The horny, dark calluses are supposed to have passed on to the descendants in Kammerer's test arrangements. The breeding of six generations of the midwife toad with this trait is said to have succeeded before the line became extinct. Out of enthusiasm for this discovery, Kammerer kissed a toad, which earned him the nickname “toad kisser”.

In 1923 Kammerer undertook lecture tours all over the world, his research results were celebrated as the greatest biological discovery of the present day, he was the most famous biologist in the world. The lecture tours through the USA turned out to be triumphal parades, the New York Times described him as the "next Darwin".

In addition to his public appearance and the associated publicity, Kammerer wrote his main work, which first appeared in English in 1924 (The Inheritance of Acquired Characteristics). The German original new inheritance or inheritance of acquired traits. Hereditary burden or hereditary discharge followed in 1925.

In 1926 he was appointed to the Soviet Academy of Sciences in Moscow , where he was to set up an Institute for Experimental Biology. His discovery made him world famous, but it also sparked doubts in the professional world and reignited the dispute between the theories of Lamarck and Charles Darwin . One of his opponents, the American zoologist Gladwyn Kingsley Noble , curator for reptiles at the American Museum of Natural History, finally traveled to Vienna, together with Hans Leo Przibram, to discover the last remaining specimen of the midwife toad, which Kammerer had served as evidence and that the war had survived undamaged to examine.

On August 7, 1926 in the British journal published Nature a devastating article, the nuptial pads in the Noble midwife toad as simple forgery exposed. The corneal dots turned out to be black ink sprayed under the skin, created by Kammerer or one of his colleagues. This was a scientific bomb and meant Kammerer's ruin. The forgery, however, turned out to be so primitive and obvious that the question arose how it could have escaped microscopic examination by dozens of scientists in previous years. To this day there is no answer to the question of whether Kammerer was really a forger or whether he was the victim of a plot of envious colleagues. The Chilean biologist Alexander Vargas, for example, takes the view that Kammerer's results can be explained epigenetically , i.e. through the environmental shutdown of certain genes, and calls for new experiments on midwife toads to be clarified. Vargas et al. also argued in 2016 that recent discoveries in the field of epigenetics support the thesis that Kammerer did not falsify his experiments and that his results are in line with the latest epigenetic findings.

Suicide

On September 22, 1926, Kammerer wrote a letter to the Communist Academy in Moscow in which he resigned from his post and at the same time asserted that he had nothing to do with the forgeries, neither with the remaining midwife toad nor with the salamander, which also had traces of ink had been found. The letter concluded:

"I see myself unable to endure this frustration of my life's work and hopefully I will find courage and strength to put an end to my missed life tomorrow."

Then Kammerer traveled to Puchberg am Schneeberg , a recreation area near Vienna, and spent the night at the Hotel Zur Rose. The next morning he set out for Himberg , where he drew the weapon he had brought with him on Theresienfelsen. He aimed her at the left side of his head and shot himself.

Hans Leo Przibram always remained convinced of the authenticity of Kammerer's observations and repeatedly stated in private conversations that he believed he knew who had committed the forgery to compromise Kammerer's, but could not make it public due to a lack of sufficient evidence. He wrote in the obituary:

“It seems impossible to him to repeat the same thing again, to the boredom, the same attempts, exposed to the same hostility, and so this time he achieved what he had threatened several times before. In his unfortunate act of September 23, 1926, both his ambiguous disposition and the adverse external factors played a part. "

Appreciation

In 1930 the Kammerergasse in Vienna- Döbling (19th district) was named after him.

Film, theater and literature

- Salamandra (Soviet film), produced in 1928 with the support of People's Commissar Anatoly Lunacharsky , who also appeared in the film, as did his wife Natalja Rosenel , who played the leading female role. The film ends with Kammerer's triumphant arrival in the Soviet Union.

- In Joshua Sobol's polydrama Alma - A Show Biz ans Ende (1996), Paul Kammerer appears as a lover of Alma Mahler and is named Krötenficker by the painter Oskar Kokoschka and suspected of being the father of her child. His obsession for the midwife toad and his successes in Russia are also discussed in the piece.

- In the 2016 novel Toad Love by the Austrian author Julya Rabinowich , Paul Kammerer is one of the three main characters (alongside Alma Mahler-Werfel and Oskar Kokoschka). ISBN 978-3552063112

Publications

- From 1899 to 1908 Kammerer wrote more than 130 articles, contributions and research reports for the biological research institute in Vienna's Prater

- About the way of life of the pointed-headed lizard ( Lacerta oxycephala , Dum. Bibr.). In: Sheets for aquarium and terrarium science. Stuttgart 1903

- Artificial melanism in lizards. 1906

- Inheritance of forced color changes I and II: induction of female dimorphism in Lacerta muralis , of male dimorphism in Lacerta fiumana . 1910

- Mendelian rules and inheritance of acquired traits. In: Negotiations of the Natural Research Association in Brno. 1911

- About acquisition and inheritance of musical talent. 1912

- Nature library. Determination and inheritance of sex in plants, animals and humans, How the chorus of stars stands around the sun, The marine mammals. Thomas Verlag, Leipzig, around 1912

- Are we slaves of the past or foremen of the future? In: Series of publications of the Monistenbund . No. 3, Vienna 1913

- Cooperatives of living beings based on mutual benefits (symbiosis). With 8 picture panels. Strecker & Schröder, Stuttgart 1913

- Determination and inheritance of sex in plants, animals and humans. With 17 illustrations in the text. Theodor Thomas Office of the German Natural Science Society, Leipzig undated (approx. 1913)

- Two years of “General Life Teaching”. Cottage Lyceum 1913/1914

- Feeling and mind. Reprint of the monthly sheets of the German Monist Association Hamburg local group, 1914

- Inheritance of Forced Color Changes VI. The color of the fire salamander (Salamandra maculosa Laur.) In its dependence on the environment. In: Biomedical and Life Sciences. Volume 12, Number 1, December 1914, Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 1914

- General biology. (= The world view of the present. An overview of the work and knowledge of our time in individual representations). With 4 colored plates and 85 illustrations. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1915

- The black coloration of the island lizards and a new attempt at explanation by Robert Mertens . 1915

- Hereditary charge. Vienna Urania 1916

- Naturalist trips to the rocky islands of Dalmatia . Urania library, Vienna 1917

- Gender determination and gender reassignment. 1918

- Individual death, national death, biological immortality and other warning words from difficult times. Vienna and Leipzig, Anzengruber Verlag 1918

- Turn of mankind. Hikes in the border area between politics and science. Peace , Vienna 1919

- The law of the series. A doctrine of the repetitions in life and world events. With 8 plates and 26 illustrations. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart / Berlin 1919

- Mastery of life: laying the foundation for organic technology. Monistic Library 13, 1919

- Dark animals in the light and light animals in the dark. Natural Sciences 13, 1920

- Development mechanics of the soul. The Free Thought, Prague 1920

- The biological age. Advances in Organic Technology. Vlg. Of the groups Währing-Döbling and Hernals of the Free School Association, Vienna (approx. 1920)

- About rejuvenation and extension of personal life. The experiments on plants, animals and humans presented in an understandable way. German publishing house, Stuttgart / Berlin 1921

- Helpful relief. In: Berliner Tageblatt . 1921

- Coincidence. In: The evening . 1921

- The cycle of events. In: Berliner Tageblatt. 1921

- World echoes soul. In: The evening. 1921

- Science fountain of youth. In: The evening. circa 1921

- About rejuvenation and extension of personal life. Stuttgart 1921

- Breeding experiments on the inheritance of acquired characters. In: Nature . May 12, 1923

- The Inheritance of Acquired Characteristics. Boni and Liveright Publishers, New York 1924

- Re-inheritance or inheritance of acquired traits. Hereditary burden or hereditary discharge. With 44 illus. Seifert Verlag, Stuttgart-Heilbronn 1925

- The riddle of inheritance. Basics of general genetics. Ullstein, Berlin 1925

- Way of life of the lizards on the smallest islands. Stuttgart 1925

- The species change on islands and its causes determined by comparison and experiment with the lizards of the Dalmatian islands. Vienna & Leipzig, 1926

- Letter to the Moscow Academy. In: Science . 64, 1926

- Gender, reproduction, fertility. A biology of procreation (genebiotics). Drei Masken Verlag, Munich 1927

- The Biological Age: Advances in Organic Technology. Monistic library, small pamphlets of the DMB No. 33, Hamburg 1922

- Wilhelm Bölsche on his sixtieth birthday. 1921

- Natural history of street fights: To justify a mechanistic conception of history. Peace, 1919

- Organic and social engineering. no year

See also

literature

- Newspaper articles about Kammerer

- Scientist Tells of Success Where Darwin Met Failure, New York Times, June 3, 1923

- Famous European Biologist Visits Us, New York Times, November 25, 1923

- His "If" is Truly Enormous, New York Times (editorial), November 29, 1923

- Kammerer Gives Proof of Theories, New York Times, December 20, 1923

- Would Direct Evolution, New York Times, December 2, 1923

- Dr. GK Noble: Kammerer's Alytes, Nature CXVIII, August 7, 1926

- This article accused Kammerer of forgery

- Przibram, Hans: Kammerer's Alytes (2), Nature CXVIII, August 7, 1926

- EW MacBride: Kammerer's Alytes. Letter. Nature, August 21, 1926

- Kammerer Kills Self With Gun Near Vienna, New York Times, September 25, 1926

- Dr. GK Noble: Kammerer's Alytes. Letter. Nature, October 9, 1926

- Dr. Noble Shocked by Kammerer Report: Explains Article charging Scientific Fraud alleged to have led to Austrian's Suicide, New York Times, October 10, 1926

- Hans Przibram: Prof. Paul Kammerer (obituary), Nature, October 16, 1926

- Dr. Paul Kammerer. Obituary, Nature, October 30, 1926

- Obituary of Przibram, who honors Kammerer's work, but at the same time points to its speculative aspects: “Need I add that Kammerer's work on the modification of animals, especially on poecilogony and adaptation to color of background in Salamandra and the reappearance of functional eyes in Proteus kept in appropriate light, will secure him a lasting place in the memory of biologists, even if some other of his papers were open to criticism. "

- EW MacBride: Kammerer's Alytes. Letter. Nature, November 6, 1926

- Hans Przibram: Letter. Nature, April 30, 1927

- Literature on Kammerer

- Lester R. Aronson: The Case of the Midwife Toad. In: Behavior Genetics. Vol. 5, No. 2, 1975.

- William Broad & Nicholas Wade: Betrayers of the Truth. Simon and Schuster, New York 1982.

- Allan Combs & Mark Holland: The Magic of Chance. Synchronicity - a new science. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1992, ISBN 3-499-19177-6 (deals with the work of Carl Gustav Jung , Wolfgang Pauli , Kammerer, Werner Heisenberg and David Bohm ).

- Marilyn Ferguson : The Aquarian Conspiracy. Personal and Social Transformation in the 1980s. JP Tarcher Inc., Los Angeles 1980.

- Rene Freund: Land of Dreamers. Between size and megalomania. Unrecognized Austrians and their utopias. Picus, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-85452-403-X .

- Martin Gardner : In the Name of Science. GP Putnam's Sons, New York 1952.

- Sander Gliboff: "Protoplasm ... is soft wax in our hands". Paul Kammerer and the Art of Biological Transformation. In: Endeavor. Vol. 29, 4, 2005.

- Richard B. Goldschmidt: Research and Politics. In: Science . 109, 1949.

- Peter Jungwirth: theorist and practitioner of chance. In: The Standard . September 30, 2006 (album, A 5).

-

Arthur Koestler : The Case of the Midwife Toad . Hutchinson, London 1971.

- The toad kisser. The case of the biologist Paul Kammerer. Molden, Vienna / Munich / Zurich 1972. New edition 2010 Czernin Verlag Vienna with an afterword by Peter Berz and Klaus Taschwer. ISBN 978-3707603149 .

- ders .: The roots of chance. Scherz, Bern / Munich / Vienna 1972.

- Willy Ley: Salamandre e alta politica: l'affare Kammerer.

- Friedrich Lorenz : victory of the ostracized. The fate of researchers in the shadow of the ferris wheel. Globus, Vienna 1952.

- Ohad Parnes: Paul Kammerer and Modern Genetics. Acquisition and inheritance of adulterated properties. In: Anne-Kathrin Reulecke (Ed.): Forgeries. On Authorship and Evidence in Science and the Arts. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2006, ISBN 3-518-29381-8 , pp. 216–243.

- Luitfried Salvini-Plawen & Maria Mizzaro : 150 years of zoology at the University of Vienna. In: Negotiations of the Zoological-Botanical Society in Austria. No. 136, 1999, pp. 1-76.

- Stefan Schmidl: In the serial stream of events. Paul Kammerer as a scientist, music theorist and composer. In: The Tonkunst. Issue 0606, June 2006.

- ders .: Solid touchstones of reality . In: Wiener Zeitung . November 18, 2006 (extra, p. 4)

- ders .: We intended to learn from him. The encounter between Paul Kammerer and the Mahler couple. In: News on Mahler Research 60/2009. Pp. 51-59.

- Robert Silverberg: Scientists and Scoundrels. New York 1965.

- Klaus Taschwer : The Paul Kammerer case. The adventurous life of the most controversial biologist of his time . Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-446-44878-0 .

- Franz M. Wuketits : The death of Madame Curie. Researchers as victims of science. Beck, Munich 2003.

Web links

- Literature by and about Paul Kammerer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Paul Kammerer's writings on univie.academia.edu

- Paul Kammerer Papers, 1910-1972 on the American Philosophical Society website

- The riddle Paul Kammerer - The Frog King , portrait by Katrin Blawat in the Süddeutsche Zeitung , September 10, 2009

- The Kammerer case , Ö1 dimensions - the world of science, September 24, 2013, repetition March 6, 2018.

- Christa Eder: Klaus Taschwer on the spectacular "Case Kammerer" , Ö1 Leporello , October 14, 2016

Individual evidence

- ↑ Eliza Slavet: Freud's Lamarckism and the Politics of Racial Science. In: Journal of the History of Biology. Volume 41, No. 1, 2008, pp. 37, 49.

- ^ A b Veronika Lipphardt: "Jewish Eugenics"? German bio-scientists with Jewish background and their notions of Eugenics, 1900-1935. ( Biology of the Jews: Jewish scientists about "race" and heredity , p.142) ; How National Socialist is Eugenics? / What is National Socialist about Eugenics? , Conference of the History Department of the University of Basel, 2006, p. 10, footnote 35 ( PDF; 139 kB )

- ↑ AE Gaissinovitch & Mark B. Adams: The Origins of Soviet Genetics and the Struggle with Lamarckism, 1922-1929. In: Journal of the History of Biology. Vol. 13, No. 1, spring 1980, pp. 1, 26.

- ^ A b Hans Leo Przibram: Paul Kammerer as a biologist. In: Monistic monthly books. November 1926

- ↑ a b Alma Mahler-Werfel: The shimmering way. Quoted in Oliver Hilmes : Widow in madness. The life of the Alma Mahler-Werfel. Siedler, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-88680-797-5

- ↑ Alma Mahler-Werfel: My life. Fischer Verlag, 1960

- ↑ Alexander O. Vargas: Did Paul Kammerer Discover Epigenetic Inheritance? A Modern Look at the Controversial Midwife Toad Experiments. In: Journal of Experimental Zoology. 312B, 2009, p. 1 ff.

- ↑ Der Standard : Wasn't Paul Kammerer right? September 3, 2009

- ↑ The press : Will the toad kisser be kissed awake? September 11, 2009

- ↑ Vargas, Alexander et al. An Epigenetic Perspective on the Midwife Toad Experiments of Paul Kammerer (1880-1926) , Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution (2016). doi: 10.1002 / now for 22708

- ↑ Scene 11a: I wish I had 10,000 hearts , from: Alma - A Show Biz ans Ende , alma-mahler.com

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kammerer, Paul |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian zoologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 17th August 1880 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 23, 1926 |

| Place of death | Puchberg am Schneeberg |