Alma Mahler-Werfel

Alma Mahler-Werfel (born Alma Margaretha Maria Schindler, born August 31, 1879 in Vienna , † December 11, 1964 in New York , NY ) was a figure in the music, art and literature scene in the first half of the 20th century. As a girl and woman of her time, she did not develop her great musical talent professionally. Most of her compositional work, which was by no means insignificant, has been lost to this day. The wife of the composer and conductor Gustav Mahler , after his death the architect Walter Gropius and then the poet Franz Werfel had personal contact with the Secessionists , the painter Gustav Klimt and with the composer (their composition teacher) Alexander von Zemlinsky , and at times during her youth she was the lover of the painter Oskar Kokoschka . As the host of artistic salons , she gathered artists and celebrities in Vienna, then after 1938 in Los Angeles and New York. She has been portrayed many times by painters and, in the style of the times, afflicted with the cliché of a femme fatale .

overview

Alma Mahler's great talent was the music that she practiced intensively on the piano and composing in her youth. Although the musicologist Susanne Rode-Breymann can prove almost fifty piano songs in the diary suites , composed between 1898 and 1902, only seventeen of them have been known to date. The other compositions of other genres that appear in it have also been lost to this day. Rode-Breymann describes two decisive “fault lines” in the “professionalization” of Alma's musical talents. On the one hand, after years of successful piano lessons with Adele Radnitzky-Mandlick, she wanted to perfect her skills with the renowned pianist Julius Epstein , but this was prevented by her stepfather Carl Moll . On the other hand, she had to give up composing in order to marry Gustav Mahler. There are indications that during her marriage she always took her composition portfolio with her from Vienna to summer vacation and that her husband Gustav Mahler discovered her there in 1910. He then "urged" her to publish some of the songs.

Alma Mahler-Werfel accompanied important artists on their lives throughout her life and was friends with a number of European and US artists, including Leonard Bernstein , Benjamin Britten , Franz Theodor Csokor , Eugen d'Albert , Lion Feuchtwanger , Wilhelm Furtwängler , Gerhart Hauptmann , Hugo von Hofmannsthal , Max Reinhardt , Ernst Lubitsch , Carl Zuckmayer , Eugene Ormandy , Maurice Ravel , Otto Klemperer , Hans Pfitzner , Heinrich Mann , Thomas Mann , Alban Berg , Erich Maria Remarque , Friedrich Torberg , Franz Schreker , Bruno Walter , Richard Strauss , Igor Stravinsky , Arnold Schönberg and Erich Zeisl .

The painter and president of the Vienna Secession Gustav Klimt courted her when she was only 17 years old. She had a relationship with the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky based on her admiration for the composer and his recognition of her talent; with him she had, in addition to her first composition teacher Josef Labor , composition lessons for a year. Years later, on December 11, 1910 in Vienna, he premiered Alma’s 5 songs , sung by Thea Drill-Orridge with him as piano accompanist. In 1901 Alma Schindler decided to marry the composer and Viennese opera director Gustav Mahler , who was 19 years his senior ; she then had two daughters with Mahler. The last entry in her diary suites is dated January 6, 1902, two months before this wedding. With this, this immediate source for Alma Schindler's artistic development ceased.

During Gustav Mahler's lifetime she had an affair with the architect and later Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius , whom she married in 1915 after Mahler's death and a violent love affair with the painter Oskar Kokoschka. Their daughter Manon was born in 1916 . After her divorce from Gropius in 1929 she became the wife of the writer Franz Werfel, with whom she had a son who died young and with whom she emigrated to the United States in 1938 . She described her life after her wedding to Mahler in the autobiography Mein Leben .

In the numerous literature about Alma Mahler that has appeared (whereby the judgment about her personality is very different), on the one hand, the musical creativity of the protagonist is nowhere mentioned; on the other hand, reporting on biographical details degenerates "on the decline to sexualized one-dimensionality". In her two books on Alma, Rode-Breymann deals with her personal development under the conditions of her time. I.a. On the basis of the diary suites she has edited and analyzed with, much of what appears to be malicious gossip in the following quotes is put into perspective. The writer Gina Kaus declared: "She was the worst person I have known". Claire Goll wrote: "Anyone who has Alma Mahler as a wife must die". And Alma's friend Marietta Torberg said: "She was a great lady and at the same time a sewer".

In her autobiography, published in 1960, Alma Mahler-Werfel styled herself as a creative muse , and some of her contemporaries shared this judgment: Klaus Mann compared her to the intellectual muses of German Romanticism and the “proud and brilliant ladies of the French grand siècle”.

In 2004, Susanne Rode-Breymann wrote about her:

"[...] her talent as a cultural actor unfolded seamlessly, and her inspiring influence on music and cultural history cannot be overestimated."

Life

The early years

Alma was the daughter of the Viennese landscape painter Emil Jakob Schindler and Anna Sofie Schindler, née Bergen, who was trained as a singer and who, in Alma's youth, repeatedly performed Alma's songs in house and semi-public concerts. At the time of the wedding on February 4, 1879, Anna Schindler was already pregnant with Alma. The marriage began in very close quarters. The couple had to share their apartment with Schindler's artist colleague Julius Victor Berger ; after Alma's birth, he and Anna Schindler had a relationship. Berger is very likely the father of Alma's sister Margarethe Julie, who was born on August 16, 1880. In February 1881, Schindler was awarded an artist prize that put an end to the family's cramped financial circumstances. The award was followed by a series of commissions and picture sales, so that the family could afford to rent the Schloss Plankenberg estate at the gates of Vienna. In the spring of 1885, the family moved to the estate, which, in addition to the twelve-room house, also included a 1200-hectare, neglected park. Thanks to an order from Crown Prince Rudolf in 1887, Schindler had meanwhile become one of the most important artists of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. In the same year he became an honorary member of the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts , further prizes and awards followed.

Alma's mother ended the liaison with Berger after Schindler discovered her. However, a new relationship began with Carl Moll , a student and assistant to her husband, which lasted for several years and which Schindler did not see. Alma's biographer, Oliver Hilmes, sees this family life , which is characterized by secrecy and denial, as the cause of the psychological disposition of the two Schindler daughters. Hilmes also sees this as the reason for Schindler's particularly close relationship with his older daughter. Alma kept her father company for hours in the studio. In addition to promoting her awareness of art, Schindler especially encouraged her musical talent, bought a piano and also aroused her interest in literature. However, neither of the daughters received a formal education. In the winter half year they went to school in Vienna, during the summer their mother or a tutor gave their daughters lessons.

Schindler died on August 9, 1892 of the consequences of a dragged-out appendicitis . Alma was not quite 13 at the time, and she suffered badly from the loss for a long time. Rode-Breymann has differentiated the loving father-daughter relationship and the loss. The relationship between Carl Moll and Anna Sofie Schindler secretly continued for the next few years. They did not get married until November 3, 1895. Alma considered the marriage a betrayal of her late father. She also reacted with strong rejection to the birth of her half-sister Maria on August 9, 1899 - she felt neglected by her family.

The Vienna Secessionists

Carl Moll was a member of the Vienna Secession , of which he was a co-founder and vice-president. Many Viennese artists therefore frequented the Moll's house. The family's guests included writers, painters and architects such as Gustav Klimt , Joseph Maria Olbrich , Josef Hoffmann , Wilhelm List and Koloman Moser , as well as Max Burckhard , director of the Vienna Hofburgtheater . Alma got to know most of them well through discussions in which she participated, because at least she was allowed to attend dinners with these famous Viennese. Among other things, Max Burckhard sent her theater tickets, discussed individual performances with her and, like her father in the past, encouraged her interest in literature. Alma's mother was a gifted and good hostess for a “place of the exchange of ideas”, so the Vienna Secession, which was founded in April 1897 with the President Gustav Klimt, pioneered in her house “of mutual artistic inspiration”. Alma participated in these discussions; Gustav Klimt was the one who took a special liking to the then seventeen-year-old and exchanged artistic ideas with her. Even though her stepfather and mother tried to prevent a relationship between the two, Klimt's interest in her lasted for several months. When Klimt kissed her and her stepfather found out about it during a family trip to northern Italy, in which Klimt also took part, he forced his friend and artist colleague to leave. Klimt, who was known for his permissive lifestyle and was the father of at least fourteen illegitimate children at the time of his death, promised Moll to stay away from Alma in the future. He liked it, "how we painters like a beautiful child".

Alma's musical education

While Alma Schindler's school education was apparently unsystematic, she received a thorough musical education. Since 1895 she had composition lessons with the blind Viennese organist and composer Josef Labor. Adele Radnitzky-Mandlick , whom Alma confidently called “Frau Adele” “on the first pages” of her diary entries in 1898, was a student of the renowned Viennese pianist and pedagogue Julius Epstein at the Vienna Conservatory and taught Alma piano for many years. Alma Schindler developed an extensive and remarkable repertoire with her, which she regularly performed in Vienna "in the sphere of public privacy" or in public at all. Her teaching program included B. the E-flat major piano concerto by Ludwig van Beethoven. She became particularly familiar with the music of Richard Wagner, for whom she raved, and with whose fire magic from the opera Die Walküre und Liebestod from Tristan and Isolde (among others) she won laurels. Her perfect sight-reading (which she later drilled with Gustav Mahler) was also known. But when she expressed the wish to take lessons from Julius Epstein herself, her stepfather Carl Moll prevented this.

Composition lessons with Josef Labor and Alexander von Zemlinsky

From 1900 on, Alma Schindler took composition lessons from Alexander von Zemlinsky in addition to taking lessons from Josef Labor . The then 29-year-old had just become Kapellmeister at the Vienna Carltheater and was considered one of the great hopes of the Viennese music scene. This intensive lesson lasted only a year, of which Zemlinsky himself writes that he “had a direct teaching ambition” and (on August 25, 1901) he imagined that Alma “had learned a lot in the past two months”. In the literature, however, the following quote from his mouth has found a larger readership so far:

“Either you compose or you go to societies - one of the two. But rather choose what is closer to you - go to company. "

Although she later described him as a “little, ugly gnome”, Alma's admiration for his ingenuity prevailed: “Oh - a wonderful fellow and stimulating beyond measure.” Rode-Breymann gives differentiated and detailed insight into Zemlinsky's composition lessons based on his own instructions to Alma, which are kept in the Mahler-Werfel Collection in Philadelphia .

The family and friends of the family found a liaison with Zemlinsky, who comes from a Jewish family, rather unsuitable and tried to talk her out of it. Alma herself experienced an emotional roller coaster. Pathetic declarations of love and sometimes bizarre diary entries ( Alex - my Alex. I want to be your sanctuary. Pour your abundance into me , diary of September 24, 1901) alternated with humiliation and torture towards Zemlinsky, who at the time was still at the beginning of his career .

In addition to songs, she had already created other musical forms at Labor, namely around 20 piano compositions and two violin sonatas. Under Zemlinsky she ventured into choral compositions and a text by Goethe for 3 soloists and choir, after which she even looked at an opera . Susanne Rode-Breymann assumes that the songs (in other literature there are around a hundred in total) are only a tiny tip of the iceberg of all compositions by Alma Mahler-Werfel , but the least we know about those that she probably still does (despite the “ban on composing”) as Mahler's wife.

The lyricists of their songs, in order of printing, are

- 1911: Richard Dehmel , Otto Erich Hartleben , Otto Julius Bierbaum , Rainer Maria Rilke , Heinrich Heine .

- 1915: Otto Julius Bierbaum, same, Richard Dehmel, same, Gustav Falke

- 1924: Novalis (hymn), Otto Julius Bierbaum, Franz Werfel , Richard Dehmel, Novalis (hymn)

Gustav Mahler

The encounter with Mahler

Alma Schindler met the composer, celebrated conductor and director of the Vienna court opera Gustav Mahler at an evening party organized by Bertha Zuckerkandl on November 7, 1901 . Mahler apparently fell in love with the very self-assured young woman that evening. As early as November 28, he proposed to her, but also pointed out that it would not be easy to be married to him. Alma Schindler's family tried to talk her out of this connection too. Mahler, nineteen years her senior, was too old for her, impoverished and terminally ill, her stepfather Carl Moll told her, among other things. Klimt and Burckhard pointed to the Jewish descent of Mahler, who had converted to Catholicism . In contrast to Zemlinsky, with whom she had been in a relationship up until then, this did not bother her here.

Alma, however, put off the discussion with Zemlinsky. It was not until December 12th that she wrote to him that another love had suppressed him. At the same time, Mahler, who was in Berlin for the performance of his 4th symphony, sent her tender love letters. His music was incomprehensible to her:

“He thinks nothing of my art - a lot of his - and I think nothing of his art and mine a lot. That's the way it is! Now he [Mahler] keeps talking about guarding his art. I can not do that. With Zemlinsky it would have been possible, because I feel his art - he's a brilliant guy. "

In his letters to his sister Justine, Mahler also expressed doubts as to whether it was right to bind such a young woman to himself. From Dresden he wrote his bride a twenty-page letter in which he explained to her how he envisaged their future life together.

“How do you imagine such a composing couple? Do you have any idea how ridiculous and, later, how derogatory to ourselves, such a peculiar rivalry must become? What is it like when you're in the 'mood' and get the house for me, or whatever I need right now, when, as you write, you are supposed to relieve me of the little things in life? ... But that you have to become what I need if we are to be happy, my wife and not my college - that's for sure! Does this mean a break in your life for you and do you think you will have to forego an indispensable high point of being if you give up your music completely in order to own mine and also to be? "

He also made it clear to her that there was still the possibility of repentance if she could not expect to. Alma Schindler's reactions to the letter at the time can no longer be reconstructed. They got engaged on December 23rd. They married on March 9, 1902 in the Karlskirche in Vienna . It was a small wedding because Mahler wanted to avoid any social expense. In addition to the wedding couple, only the second husband of Alma's mother, Carl Moll, and Arnold Rosé , Mahler's brother-in-law, who acted as groomsmen , were present.

The marriage years

Mahler's friends as well as many from his wider circle of acquaintances reacted blankly to this marriage. Bruno Walter , who was Kapellmeister at the Vienna Court Opera at the time, wrote in a letter to his parents:

“He [Mahler] is 41 and she is 22, she is a celebrated beauty, used to a brilliant social life, he is so remote and lonely; and so one could raise a lot of concerns ... "

In her memories she herself described her financial situation at the beginning of their marriage as cramped; she found a mountain of debt of 50,000 kroner. In view of Mahler's annual salary at the Vienna Court Opera of 26,000 crowns (around 104,000 euros equivalent in 2004), to which the income from guest conductors and royalties from the sale of his works was added, this financially tense situation is difficult to understand. The couple's household included two maids and an English governess for their daughter Maria Anna, born on November 3, 1902 († July 11, 1907; died of scarlet fever and diphtheria). For 1905 it is documented that her Mahler provided a monthly household allowance of 1000 kroner (about 4000 euros equivalent in 2004). In his biography, Oliver Hilmes therefore puts forward the thesis that the tense financial situation is part of the legend that Alma Mahler-Werfel wanted to use to explain to posterity why she so often did not accompany her husband on his concert tours.

Living together with Mahler was different from what she was used to from the varied and sociable life in her parents' house. Mahler avoided companies and attached great importance to a very regular daily routine in order to cope with his large workload. From her diary entries it becomes clear that Alma Mahler felt lonely in this married life, was bored and saw degraded to the housekeeper. The feeling of inner emptiness did not change with the birth of the second daughter Anna Justina , who was born on June 15, 1904. With the knowledge and approval of Gustav Mahler, Alma had met Zemlinsky at least regularly in the spring of 1904 to make music with him. However, this collaboration did not last long. In the spring of 1906 Zemlinsky wrote her how much he missed making music with her. However, he had refused to give her lessons again.

Mahler missed the companion in his wife who shared his life with him. The break with her intensified when she engaged in a more violent flirtation with his colleague Hans Pfitzner .

On the morning of July 12, 1907, the Mahler's eldest daughter died of diphtheria after a very severe illness . The death of little Maria, which coincided with Mahler's diagnosis of a heart defect, marked a turning point in Mahler's life and also intensified the rift between the couple. In order to get over the death of her daughter, Alma Mahler took a cure while Mahler was on concert tour in Helsinki and Saint Petersburg .

Since January 1907 Mahler had repeatedly been violently attacked in the Viennese press for his leadership style as director of the Vienna Court Opera. This led to a withdrawal from Viennese musical life and increased activity in the United States. In December 1907 Mahler began an engagement at the Manhattan Opera House, and Alma accompanied him on the four-month stay in New York. While Mahler celebrated his first major success in New York with the performance of Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde , she felt lonely and isolated. Only at the end of their stay did they get to know Joseph Fraenkel , who became a close friend for both of them. The friendship was strengthened during the second stay in New York, which lasted from November 1908 to April 1909. During the six months that the couple spent in Europe, Alma Mahler was mostly on cure and lived apart from her husband. From the letters of Gustav Mahler one can conclude that Alma suffered at least one miscarriage or had an abortion performed during this period . After her third stay in New York, which lasted from November 1909 to April 1910, she went with her five-year-old daughter and her governess to Tobelbad , a small, fashionable spa town in Styria , owned by the Viennese inventor and entrepreneur Gustav Robert Paalen bought, restored and made socially acceptable. Even Walter Gropius , at the time still a largely unknown architect , was there to take the waters and Alma was presented by Paalen. In June 1910 she began an affair with him, which Mahler discovered just a few weeks later when he came across a love letter from Gropius. Gropius had addressed the letter to Gustav Mahler - by mistake, as he later put it to the Mahler researcher Henry-Louis de La Grange .

When the marriage plunged into a crisis after meeting Walter Gropius, Mahler was recommended to visit Sigmund Freud , who received him in August 1910 in the Dutch spa Leyden for four hours. Freud commented on his diagnosis to his student Marie Bonaparte :

“Mahler's wife Alma loved her father Rudolf Schindler and could only look for and love this type. Mahler's age, which he so feared, was precisely what made him so attractive to his wife. Mahler loved his mother and sought her type in every woman. His mother was mournful and suffering, and he unconsciously wanted the same from his wife Alma. "

Mahler now began to strive intensely to gain the affection of his wife. He dedicated his 8th symphony to her, which was premiered in Munich during this time and was his greatest musical triumph. In the same year he had five of the songs she composed printed and premiered in Vienna and New York. Shortly before returning to New York, however, Alma traveled to Paris to meet Gropius again before accompanying her husband to the United States for several months. From New York, too, she repeatedly assured Gropius in letters how much she loved him. In this she found support from her mother Anna Moll, who wrote warm letters to Gropius, asking him to understand that Alma could not leave Gustav Mahler now, and pointed out that both Alma and Gropius were still young and could wait. The extent to which Alma Mahler's family expected that Mahler would not have long to live in view of the identified heart defect cannot be reconstructed today.

Mahler fell seriously ill on his last trip to the USA. On February 21, 1911, despite the fever, he conducted a long and strenuous concert with works by Leone Sinigaglia, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy , Giuseppe Martucci , Marco Bossi and Ferruccio Busoni . When his condition did not improve over the next few days, the doctors found a slowly progressing heart inflammation . There were hardly any treatment options for these at the beginning of the 20th century. Alma Mahler and her husband traveled back to Europe to consult specialists from the Pasteur Institute in Paris . Even the French doctors were only able to confirm the diagnosis made by their American colleagues. A doctor brought in from Vienna recommended Alma to bring her husband back to Vienna. On the evening of May 12th they reached Vienna. A few days later, on May 18, 1911, Gustav Mahler succumbed to his illness.

Mourning period

Although after Mahler's death there was nothing to be said against continuing and intensifying her relationship with Gropius, Alma Mahler broke off her relationship with Gropius. In his letters to her, Walter Gropius had expressed his shock that, despite the oaths of loyalty to him, there had been sexual intercourse between Alma and Gustav Mahler shortly before his death. He avoided a possible reunion in September 1911. At a meeting in December of that year, tension arose between the two, which further cooled their relationship.

In Vienna, thanks to the widow's pension and Mahler's legacy, Alma was a wealthy woman with considerable wealth. In autumn 1911 she had a brief relationship with the composer Franz Schreker . Joseph Fraenkel, who was friends with the Mahler couple in New York, also came to Vienna and asked for Alma's hand. In her diary she referred to him as a poor, sick, elderly man who was only concerned with his serious intestinal disease. She refused the marriage proposal. She paid more attention to the biologist Paul Kammerer , who had greatly admired Mahler and to whom Alma Mahler attributed the fact that Gustav Mahler was so successful as a composer. He offered the in no way trained Alma Mahler a position as an assistant in his institute. By her own account, she actually worked on his experiments on praying mantises and midwife toads for several months . The admiration that the married chamberlain showed her, however, took on increasingly eccentric forms. Among other things, Kammerer threatened to shoot himself at Mahler's grave if she did not return his love. In the spring of 1912 she ended her work at the institute.

Alma's half-sister Margarethe Julie - at that time still regarded by Alma as the daughter of her father Emil Jakob Schindler - was diagnosed with dementia praecox at the same time . Anna Moll persuaded her daughter that her father's diphtheria was the cause of Margarethe Julie's mental illness. For years this caused Alma Mahler to worry about becoming mentally ill as well. It was not until 1925 that she discovered that Julius Victor Berger was the father of Margarethe Julie. The half-sister, who died in a sanatorium in 1942, is no longer mentioned in Alma Mahler's diaries.

The affair with Oskar Kokoschka

Alma's stepfather Carl Moll was one of the patrons of the expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka . Among other things, he commissioned him to make a portrait of his stepdaughter. During dinner on April 12, 1912, at which Carl Moll introduced him to Alma Mahler, Kokoschka fell in love with the widow:

“How beautiful she was, how seductive behind her mourning veil! I was enchanted by her! And I got the impression that she didn't really care either. After dinner she even took me by the arm and pulled me into an adjoining room, where she sat down and played the 'love death' for me. "

Just two days later, Kokoschka sent her her first love letter, which was to be followed by four hundred more. The affair between the two was very much marked by Kokoschka's jealousy .

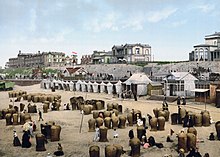

In retrospect, Alma Mahler described the relationship as a three-year love struggle: "Never before have I tasted so much cramp, so much hell, so much paradise." Kokoschka's jealousy was not only for the men she met, but also for the late Gustav Mahler. In the letters that Kokoschka Alma wrote while she was in Scheveningen in May 1912 , he implored her to focus all her thoughts on him. When she was in Vienna, he would occasionally watch outside her apartment to make sure she was not receiving any male visitors. After her second trip to Scheveningen in the summer of 1912, he asked her to withdraw completely from society and to be there only for him.

As with Mahler before, Kokoschka's friends were not taken with the relationship with Alma. Adolf Loos , who was part of Kokoschka's close circle of friends, repeatedly warned him of their bad influence. Kokoschka's mother was also firmly against the connection. Kokoschka, on the other hand, made efforts to persuade Alma Mahler to get married. Alma Mahler was probably already pregnant by Kokoschka in July 1912. However, in October she had the child aborted. The pain that Alma inflicted on him with the abortion of their child was dealt with in 1913 in the two studies Alma Mahler with Child and Death and Alma Mahler spins with Kokoschka's intestines , which were on view in the Essl Collection in Klosterneuburg .

Alma was still in correspondence with Walter Gropius. However, she had left him in the dark about her relationship with Kokoschka. However, in 1913 Gropius saw Kokoschka's painting Double Portrait of Oskar Kokoschka and Alma Mahler , which was shown in 1913 at the 26th exhibition of the Berlin Secession (today Museum Folkwang , Essen ). Alma is shown in this painting in red pajamas and offers Oskar Kokoschka her hands as if to be engaged. Correspondence with Gropius then came to a complete standstill in the course of 1913.

The relationship with Kokoschka also grew cooler. Alma regularly avoided Kokoschka's repeated attempts to get her to marry by traveling long distances in the company of Lilly Lieser , one of her few female friends. However, in late 1913 and early 1914, Kokoschka created a four-meter-wide fresco that adorned the fireplace in her spacious summer house in the small Austrian community of Breitenstein in the Semmering area . As in some paintings before, Kokoschka made his relationship with Alma the subject of the fresco. At the same time, the relationship between them cooled down more and more. Kokoschka accused Alma of superficiality and inner emptiness in his letters.

“Almi, you can't be foolish once and wise once at will. Otherwise you lose both of your luck. And you will become a sphinx who can neither live nor die, but who kills the man who loves her and who is too moral to take back this love or to cheat for his sake "

In May of the same year, Alma recorded in her diary that, from her point of view, the relationship with Kokoschka had ended. The men with whom she had closer relationships over the next few months included the industrialist Carl Reininghaus and the composer Hans Pfitzner . The relationship with Kokoschka did not really end until the first year of the First World War . Oskar Kokoschka volunteered and through the mediation of his friend Adolf Loos was accepted into Dragoon Regiment No. 15, the most distinguished cavalry regiment of the Austrian monarchy. The horse he needed to join this cavalry regiment he bought with the money he received from the sale of the painting The Bride of the Wind . The bride of the wind represents a tightly embraced pair of lovers who have the features of Kokoschka and Alma. It is now in the Kunstmuseum Basel .

Walter Gropius

While the relationship with Kokoschka was still in place, Alma resumed correspondence with Gropius. In February 1915 she traveled to Berlin, accompanied by Lilly Lieser, to see Gropius. In her diary, she noted that it was her declared goal to "bend back to the bourgeois son of the muse". The reunion between the two was so stormy that Alma worried about being pregnant again after her return to Vienna. In her letters to Gropius, she assured him of her love and implored her wish to finally become his wife. Correspondence with Kokoschka did not end until April 1915 when he volunteered for front duty.

While Kokoschka and Gropius were doing their military service, Alma began to take up the social life that established her reputation as an artistic muse. As usual from her parents' house, she received numerous artists in the salon of her Viennese apartment on Elisabethstrasse. Gerhart Hauptmann , Julius Bittner , Franz Schreker , Johannes Itten , Richard Specht , Arthur Schnitzler and Siegfried Ochs as well as their old admirers Paul Kammerer and Hans Pfitzner frequented there. At the same time, she began to portray herself more and more as the guardian of the musical legacy of her late husband Gustav Mahler. The writer Peter Altenberg caricatured the emotional participation of Alma, wrapped in mourning clothing, in a performance of Mahler's songs for the death of children so aptly as staged that Alma thought about revenge and wanted to use both Kokoschka and Kammerer for it. The S. Fischer publishing house refrained from including this satire in later editions of Altenberg's "Fechsung" collection.

The marriage with Gropius

Walter Gropius and Alma were married on August 18, 1915 in Berlin. Gropius had been given special leave for this and had to return to the front two days later. Kokoschka was seriously wounded at the front on August 29th. In Vienna one even assumed his death. Alma responded to the false news of his death by fetching the letters she had written to him from Kokoschka's studio and also taking sketches and drawings.

In his biography of Alma Mahler-Werfel, Oliver Hilmes describes the marriage between Walter Gropius and Alma Mahler as a relationship doomed to failure from the start. While he suspects that Gropius actually felt a lot for Alma and possibly also tried to normalize his life, which had been thrown out of joint by the First World War, with his marriage, he sees Alma Mahler's reason for the marriage as a mixture of social conventions , inner emptiness and disorientation.

The newly married woman continued her life in Vienna after her marriage to Walter Gropius and received numerous musicians, conductors and artists in her Viennese salon, who came to see her as Mahler's widow. She even had the writer Albert von Trentini court her. As before, she saw herself primarily as Gustav Mahler's widow and felt her marriage to Gropius as a social decline. Although her last name was now officially Gropius, she occasionally referred to herself as Alma Gropius-Mahler or Mahler-Gropius. In one of her letters to Gropius she wrote: "... that the doors of the whole world, which are open to the name Mahler, fly shut before the completely unknown name Gropius." She only announced the marriage to some acquaintances such as Gerhart Hauptmann's wife when one could no longer overlook her pregnancy. And when Gropius's mother obviously complained to her son that her daughter-in-law hadn't visited her when she was in Berlin for a Mahler concert, she let Gropius know that her mother-in-law would have found out about it in time from the newspapers, if she had actually stayed in Berlin.

Gropius was fighting on the Vosges front at this time and was repeatedly involved in battles. He was also not present during the birth of his daughter Manon on October 5, 1916, but gave Alma to Edvard Munch's painting Summer Night on the Beach (also: Midnight Sun ) as a thank you for the strenuous birth. Alma Mahler-Gropius' letters do not suggest that she was aware of the dangers her husband was exposed to at the front. Her letters alternate violent complaints, reports of trivialities and detailed erotic fantasies. She was shocked when her husband was transferred to an army intelligence school as a regimental adjutant , where he was responsible, among other things, for training dogs that were used as medical and reporting dogs at the front. In one of her letters to him, she called this task subaltern and unworthy, ugly for him and her. "My husband has to be first class," she wrote to him.

separation

On November 14, 1917, the writer Franz Blei brought the 27-year-old Franz Werfel with him to one of the evening parties in Alma's salon. Alma had set his poem The Recognizing One to music two years earlier , but had not yet met Werfel, who had been known primarily as a poet, personally. At first she found Werfel not very attractive physically and was bothered by the fact that he was Jewish: “Werfel is a bow-legged, fat Jew with bulging lips and slender eyes that swim! But he wins the more he gives himself. ”Unlike Gropius, who was not very interested in music, Werfel shared Alma's interest in music. He visited her more often in the following weeks to make music with her, and gradually she began to take an interest in him. When Gropius returned on December 15 on the occasion of his Christmas vacation, she reacted coldly and negatively to him. Violent arguments quickly developed between the two of them. Gropius' vacation ended on December 30th and she reacted with relief to his departure.

The love affair with Werfel probably began at the end of 1917, because when Alma Mahler-Gropius found out in early 1918 that she was pregnant, she was convinced that Werfel was the father. The son Martin Carl Johannes was born on August 2nd as a premature birth caused by sexual intercourse with Werfel. Gropius, who was given home leave shortly after the birth, had to discover that he was probably not the father of the child when he happened to witness a telephone conversation between his wife and Werfel. The son, who apparently suffered from a head of water , died on May 15, 1919. Werfel suffered from the death because he felt responsible for the premature birth.

The marriage between Gropius and Alma Mahler was divorced on October 16, 1920. For a long time, custody of their daughter Manon was disputed between the two spouses. Soberly stated Gropius in a letter to his still-wife, which he wrote to her on July 18, 1919:

“Our marriage was never a marriage. The woman was missing in her. For a short time you were a wonderful lover to me and then you left without being able to survive the disease of my war withered with love and mildness and trust - that would have been a marriage. "

Although the relationship between Werfel and Alma Mahler was already publicly known at the time, Gropius took the blame for the failure of the marriage on himself. In a farce ready for the theater , he let himself be caught red-handed with a prostitute in a hotel room in order to obtain a quick divorce.

Franz Werfel

From 1919 on Alma lived with Werfel. The relationship with the writer became public when Max Reinhardt , then director of the Deutsches Theater in Berlin, invited Werfel to read aloud from his new trilogy Spiegelmensch in mid-April 1920 . This was a great honor for Werfel. Alma Mahler accompanied the writer to Berlin and was always at his side.

Werfel was eleven years younger than his partner and at the beginning of their relationship a well-known expressionist poet. But he lacked the energy to stand out as a writer of great novels. He was known for his lively relationships with the artistic circles of Vienna, with whose representatives he roamed the bars and cafés of the Austrian capital for nights. This changed through the relationship with Alma Mahler. Werfel himself once referred to his lover and future wife as the “keeper of the fire”, who demanded a daily workload from him and put him under pressure to implement his numerous creative ideas, which he had previously lacked the energy to realize. She made her remote house in Breitenstein am Semmering available to him as a work residence. When Alma Mahler went away, Werfel fell back into his old way of life and wandered through Vienna at night with Ernst Polak , Alfred Polgar or Robert Musil .

Anna Mahler , the daughter from her first marriage to Gustav Mahler , married the conductor Rupert Koller at the age of seventeen , but left him a few months later. In 1922 she began a relationship with the composer Ernst Krenek , who paints a critical picture of Alma Mahler in his memoirs, Im Atem der Zeit .

Krenek first met the once celebrated Viennese beauty when she was in her early forties. He described Alma Mahler as a somewhat corpulent “splendidly rigged battleship” and wrote: “She was used to wearing long, flowing robes so as not to show her legs, which were perhaps a less remarkable detail of her build. Her style was that of Wagner's Brünhilde, transported into the atmosphere of the bat. "

Krenek, on the other hand, was impressed by their inexhaustible and apparently indestructible vitality. He found food and drink to be the basic elements of their approach to bind people to themselves. He only seldom met her without being served “refined, complicated and obviously expensive dishes and, above all, plenty of heavy drinks”. On the other hand, he was irritated by the sexually charged atmosphere in the Mahler-Werfel house: “Sex was the main topic of conversation, and mostly the sexual habits of friends and enemies were noisily analyzed, with Werfel trying to add a serious and intellectual note by solemnly talking about the World revolution spread. "

Fundraising

In the early 1920s, Alma Mahler acquired a third residence in addition to the apartment in Vienna's Elisabethstrasse and the house on Semmering . It was a small, two-story palazzo not far from the Frari Church in Venice . However, there was hardly anything left of Gustav Mahler's fortune, as she had invested a large part of it in war bonds in 1914 . The remainder was eaten up by inflation in the 1920s. In addition, since Mahler's symphonies were only played occasionally during these years, royalties were low. The lush lifestyle that she led in the early 1920s could not be financed from it.

In order to raise money, Alma Mahler commissioned her son-in-law Ernst Krenek , among others , to transcribe the fragment of Gustav Mahler's 10th Symphony into a completed work. Krenek refused this because of his respect for Mahler's work, but edited the almost complete movements Adagio and Purgatorio , which were premiered on October 12, 1924 under the direction of Franz Schalk in the Vienna State Opera. Alma's friend Willem Mengelberg performed these fragments of the symphony in Amsterdam and New York , and Alma Mahler made it a point to receive the respective royalties in US dollars.

At the same time as the premiere in Vienna, Alma Mahler had a collection of Mahler's letters edited by her edited by the newly founded Paul Zsolnay Verlag , with whose owner family she was friends, and a facsimile of the 10th Symphony published. The latter has been criticized again and again to this day. Mahler had been working on the symphony on his deathbed and the sheet music bears numerous very personal notes, which among other things also reflect his desperation over his wife's affair with Gropius ("Live for you, die for you! Almschi!"). In addition to Krenek, Bruno Walter Alma Mahler also advised against posthumous publication for this reason.

In parallel to the publication of the Mahler letters, Alma Mahler also published her own compositions. Five of her hitherto unpublished songs were published by the Austrian publishing house Weinberger, and the Universal Edition brought out the Four Songs, already published in 1915 with the support of Gustav Mahler, in a second, albeit small, edition.

Franz Werfel, however, was brought in as the high earner in the Mahler-Werfel house. His tragedy Schweiger , published in 1923, was rejected by the critics and Werfel's friends, such as Franz Kafka , were also opposed to the play. But both the premiere in Prague and the German premiere in Stuttgart were a great success with the public. In April 1924 the first novel Werfels was published by Zsolnay Verlag and established his fame as a novelist. Verdi - the opera's novel was sold 20,000 times within a few months. Alma Mahler had given Werfel considerable support in his work and followed his work critically. As Alma Mahler's temporary son-in-law Ernst Krenek critically commented, it was clear to her that more money could be made with a novel than with the poems, dramas and novels that Werfel had published so far:

“With a truly admirable foresight, she must have recognized Franz Werfel's potential for what she wanted to make of him, and with just as amazing energy she decided to rely on her mental powers to bring about the desired change ... I don't remember whether it was it was during my first or second summer in Breitenstein that he finished his Verdi novel. ... Alma made her deliberate remarks, which amounted to the fact that the book had to be as good as any one of 'these classics', but at the same time suitable for sale on the station newsstands. And Werfel turned out to be marvelously adaptable. The expressionist's efforts to reach the sky were gone ... "

These fundraising efforts quickly proved successful. Already in 1925 she was able to support Alban Berg financially with the printing of his opera Wozzeck . Alban Berg dedicated this opera to her out of gratitude.

In 1926 Werfel was awarded the Grillparzer Prize by the Austrian Academy of Sciences and Max Reinhardt performed his play Juarez and Maximilian at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin with great success . In 1929, when Alma Mahler finally gave in to Werfel's insistence and married him on July 6th, Werfel was an established writer who was one of the most widely read in the German language.

Radicalization

Alma Mahler and Franz Werfel married in 1929, although massive crises in their relationship had repeatedly occurred in the 1920s. Alma Mahler had already recorded in her diary on January 22, 1924:

“I don't love him anymore. Inside, my life is no longer related to his. He's shrunk back down to the little, ugly, fat Jew of the first impression. "

Such diary entries are not atypical of Alma Mahler's emotional imbalance and a few days later may no longer have the meaning that they suggest. Oliver Hilmes suspects that the marriage was also a reaction by Alma Mahler to her increasing age and physical decline, which she also mentions several times in her diaries. She had not lived alone since she was young and may have been concerned that she would no longer be able to find a suitable partner. Typical of the years of marriage up to emigration in 1938, however, is a gradual drifting apart of the two partners. They both spent long periods of time apart. Above all, Alma Mahler avoided meeting Werfel's family by traveling alone to Venice, and Franz Werfel spent a lot of time in the house on Semmering or in Santa Margherita Ligure in the province of Genoa , living in a hotel there, working on his novels to continue working. However, it may also have contributed to the fact that Franz Werfel did not feel comfortable in the pompous villa that Alma Mahler acquired in 1931 in Vienna's posh district Hohe Warte . Different political opinions also contributed to the growing gap between the two partners.

In the climate of increasing political radicalization, the anti-Semitism that had always existed at Alma Mahler continued to grow. She made it a condition that Werfel had to leave the Jewish religious community before the wedding. Werfel had followed this request, but a few months later, namely on November 5, 1929, converted back to Judaism without Alma's knowledge. Elias Canetti , who later won the Nobel Prize for Literature and was a fan of Mahler's daughter Anna, also recounts in his autobiography Das Augenspiel how Alma Mahler himself contemptuously described Gustav Mahler as a “little Jew”. Alma Mahler had a positive attitude towards the German National Socialists . She did not perceive the political disputes as a struggle between political ideologies, but as a conflict between Jews and Christians. Even in the Austrian civil war after Engelbert Dollfuss eliminated parliament in 1934, she was clearly on the side of the Austrofascists . The Spanish Civil War was another point of contention between the spouses. Alma Mahler-Werfel took the side of the Franquists , while Franz Werfel took the republican side.

Since the early 1930s, the Viennese villa has been increasingly frequented by guests who corresponded to Alma Mahler-Werfel's political direction. In addition to Kurt von Schuschnigg , the former Federal Chancellor Rudolf Ramek and the head of the Austrian war archives Edmund Glaise von Horstenau frequented the city . The close friendship that developed between the Austrian politician Anton Rintelen and Alma Mahler-Werfel in the early 1930s was incomprehensible to Franz Werfel, who had advocated the idea of communism as recently as 1918 . In addition, well-known church representatives like the cathedral organist Karl Josef Walter and the church music advisor Franz Andreas Weißenbäck frequented her house . The fifty-year-old fell in love with the 37-year-old theology professor and religious priest Johannes Hollnsteiner , Schuschnigg's confessor, who saw Hitler as a kind of new Luther , and an affair broke out between the two. In order to avoid discovering the liaison, Alma Mahler-Werfel even rented a small apartment so that she could meet with him as undiscovered as possible. Franz Werfel found out when his books were burned in Germany in the campaign against the un-German spirit ordered by Joseph Goebbels .

In 1935, at the age of only 18, Manon Gropius, Alma Mahler-Werfel's daughter with Walter Gropius, died of polio . Alma Mahler-Werfel had attributed the grace and beauty of the young girl, also vouched for by other contemporaries, to the fact that she was the only one to conceive this child with an " Aryan ". Claire Goll later described her other children contemptuously as "half-breeds". The funeral of the young Manon Gropius was a major social event in Vienna. Johannes Hollnsteiner, his mother's lover, gave the funeral speech in which he spoke of the death of an angel. Alban Berg dedicated his concerto for violin and orchestra to her , which he called In Memory of an Angel . Ludwig Karpath wrote in his necrology in the Wiener Sonn- und Mondags-Zeitung of a wonderful creature of purity and chastity of sensation.

Werfel's political stance during these years is sometimes difficult to interpret. Political naivety, personal obligations and the influence of his wife may have played a role when the writer, who had long been banned by the Nazis in Germany, went on excursions with the Schuschnigg couple and his wife in a limousine provided by Benito Mussolini in 1935 . When Kurt von Schuschnigg's wife died in a car accident in 1935, Werfel wrote her obituary in which he described Schuschnigg as an extraordinary person.

“People starve in dungeons, but the Werfels eat out of the crib and lick their hands. The embodiment of the human dirty soul "

commented on this in the Arbeiter-Zeitung published in Brno .

Unlike in National Socialist Germany, Jews were not excluded from public life at this time. The Austrian corporate state under Schuschnigg's government was anti-Semitic from 1937 onwards, but it was precisely in contrast to Nazi Germany that it was tolerant and cosmopolitan. Gustav Mahler's 25th anniversary of death was celebrated between April 26 and May 24, 1936 when the Vienna Philharmonic and the Vienna Symphony performed a number of his works and Bruno Walter - like Mahler also a Jew - conducted. Alma Mahler-Werfel invited to the events which, according to the program leaflet, were held under the patronage of Federal Chancellor Dr. Kurt v. Schuschnigg took place, also the diplomatic corps of the Netherlands , Sweden , Belgium , Poland , Hungary and France . In 1937 Franz Werfel was awarded the "Austrian Cross of Merit for Art and Science".

emigration

The villa on the Hohe Warte, in which Manon Gropius had died, was increasingly perceived by Alma Mahler-Werfel as a house of misfortune. Franz Werfel only rarely lived there and preferred - perhaps also because of his wife's high alcohol consumption - to work in hotel rooms outside of Vienna. Alma Mahler therefore wanted to rent out the villa. On June 12, 1937, she gave a final farewell party in the villa with its 20 rooms, at which a large part of Viennese society and, above all, many cultural workers were again present. In addition to Bruno Walter and Alma's first lover, Alexander von Zemlinsky, the guests included artists such as Ida Roland , Carl Zuckmayer , Egon Wellesz , Ödön von Horváth , Siegfried Trebitsch , Arnold Rosé , Karl Schönherr and Franz Theodor Csokor .

Although the relationship between Franz Werfel and Alma Mahler-Werfel had not yet re-established, they set off on December 29, 1937 on a trip that took them first to Milan and then via Naples to the island of Capri . There they learned that Federal Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg had signed the so-called Berchtesgaden Agreement with Nazi Germany on February 12, 1938 , which - for the couple probably not yet fully foreseeable at the time - heralded the end of Austria as an independent state. At the end of February Alma Mahler-Werfel traveled back to Vienna, alone and incognito, where she closed all bank accounts and had the money smuggled into Switzerland in a money belt through her long-time confidante Ida Gebauer . On 12 March 1938, the date on which the so-called Anschluss was completed to the German Reich, she said goodbye to her mother and traveled with her daughter as a " half-Jew was now threatened," through Prague and Budapest after Milan, where Franz Werfel was waiting for them.

The tension between the two spouses continued. In her diary, Alma Mahler-Werfel wrote of two people who, after being together for twenty years, speak two different languages and whose “racial alienation” could not be bridged. She found Werfel's concern for his family exaggerated. Nevertheless, both of them settled down together in the southern French fishing village of Sanary-sur-Mer not far from Marseille , where other German emigrants such as Thomas and Heinrich Mann , Lion Feuchtwanger , Bertolt Brecht , Ludwig Marcuse , Franz Hessel and Ernst Bloch temporarily stayed until 1940 . At least at this point in time, Alma Mahler-Werfel was considering divorce from Werfel and had the Reich Propaganda Office demonstrated whether she was welcome in Austria. Why she ultimately decided to follow her husband into exile in the United States can no longer be understood. Her biographer Hilmes suspects that the now almost 60-year-olds are afraid of loneliness, because her last lover Johannes Hollnsteiner - who was sent to the Dachau concentration camp by the Nazis as a supporter of the Schuschnigg government in March 1938 - was no alternative.

Emigration to the United States was very difficult. When they left Sanary-sur-Mer in June 1940, the Wehrmacht had already occupied Paris. The Mahler-Werfel couple did not have a visa to travel to the United States and, among other things , had to wait five weeks in the pilgrimage site of Lourdes to obtain a travel permit to Marseille. In Marseilles they met Heinrich Mann, his wife Nelly and his nephew Golo Mann , with whom they stayed until their arrival in the United States. It was thanks to the American journalist and Quaker Varian Fry that they managed to leave the country . Fry was a member of the Emergency Rescue Committee , which mainly supported intellectuals in their escape from France. He took the group of five to the Franco-Spanish border. There they had to cross a mountain range on foot, which brought the almost 70-year-old Heinrich Mann and the overweight Franz Werfel to their physical limits.

"I have the feeling that without her [Alma Mahler-Werfel] Franz would have simply stayed where he is and perished"

Carl Zuckmayer wrote to a friend after he learned the details of the escape. In Barcelona , Fry organized flight tickets to Lisbon , from where they took the Greek ocean liner Nea Hellas to New York. They arrived there on October 13, 1940.

Exile in California

The Mahler-Werfel couple settled in Los Angeles , where numerous German and Austrian emigrants lived. In addition to Thomas Mann, Max Reinhardt, Alfred Döblin , Arnold Schönberg and Erich Wolfgang Korngold , Friedrich Torberg , among others, lived here , who over the next few years developed a particularly close relationship with both Franz Werfel and Alma Mahler-Werfel.

Her financial means were sufficient to initially settle in a residential area above the city and hire a domestic servant who also acted as valet for Werfel as well as chauffeur and gardener. As in Europe, many cultural figures frequented their homes in Los Angeles. In particular, Thomas Mann and his wife Katia were regular guests. During this time, Werfel worked intensively on his novel about Bernadette Soubirous . Albrecht Joseph supported him as secretary , who reported an experience that was characteristic of the coexistence of Werfel and Alma Mahler-Werfel:

“They argued about the news, which, as always, was pretty bad. Alma took the position that it couldn't be otherwise, since the Allies - America had not yet entered the war - were degenerate weaklings, and the Germans, including Hitler, supermen. Werfel ignored this nonsense, but Alma did not give in. The pointless argument lasted about ten minutes, then Werfel patted me on the shoulder and said, 'Let's go downstairs and work.' In the middle of the narrow spiral staircase he stopped, turned to me and said: 'What can you do with a woman like that?' He shook his head: 'Don't forget that she's an old woman.' "

Werfel's novel, Bernadette's Song of Bernadette Soubirous, based on a vow , became a US bestseller, selling 400,000 copies within a few months. Twentieth Century Fox acquired the film rights . Reviews appeared in numerous US daily newspapers and radio interviews with Werfel were broadcast nationwide.

The improvement in their financial situation that accompanied their success as a writer enabled the couple to acquire a more comfortable villa in Beverly Hills . However, Werfel retired to Santa Barbara to write . Oliver Hilmes suspects that only this spatial separation enabled the couple to find each other again and again despite major differences and to keep their relationship stable for over 25 years.

Not far from the new villa lived not only Friedrich Torberg , but also Ernst Deutsch , a childhood friend of Werfels, the Schönbergs and the Feuchtwangers. Erich Maria Remarque became Alma Mahler-Werfel's new drinking companion there, who gave her a bottle of Russian vodka wrapped in a huge bouquet after the first night of partying.

Franz Werfel suffered a serious heart attack on the night of September 13, 1943, from which he only slowly recovered in the first half of 1944. The couple's entourage now also included a personal physician engaged by Alma Mahler-Werfel. In the summer of 1945, Werfel had just finished his utopian novel Star of the Unborn , but his health deteriorated again. On August 26, 1945, he died of another serious heart attack. At the funeral on August 29th, Bruno Walter and the singer Lotte Lehmann took over the musical design. Alma Mahler-Werfel herself did not attend the funeral. The funeral speech was held by Father Georg Moenius , with whom Werfel had discussed theological issues while he was working on The Song of Bernadette . In his speech, he discussed the baptism rites of the Catholic Church, which has led to speculation that Alma Mahler-Werfel had performed the emergency baptism of Werfel when she found her dying husband. Werfel had expressed general sympathy for the Catholic faith, but had confessed to Judaism several times and, among other things, stated in a letter to the Archbishop of New Orleans in 1942 that, in view of the persecution of the Jews, he was reluctant to sneak away from the ranks of those persecuted at this hour .

The great widow

As La grande veuve , as the great widow of Gustav Mahler and Franz Werfels, Thomas Mann described Alma Mahler-Werfel in the following years. Claire Goll's judgment of the widow, who in Goll's opinion after Werfel's death, had cast her eye on Bruno Walter, was more malicious. She compared Alma Mahler, whose character her fondness for champagne and Bénédictine had n't gotten, with a Germania that was swelling apart and wrote about her:

“To freshen up her fading charms, she wore gigantic hats with ostrich feathers; it was not known whether she wished to appear as the mourning horse in front of a hearse or as the new d'Artagnan. In addition, she was powdered, made up, perfumed and drunk. This swollen Valkyrie drank like a hole. "

Alma Mahler-Werfel only visited her old hometown Vienna briefly again in 1947. Her mother died in autumn 1938; her stepfather Carl Moll, her half-sister Maria and her husband Richard Eberstaller , 1926–1938 President of the ÖFB , who had both been long-time members of the NSDAP , committed suicide in April 1945. During her visit, she was mainly concerned with settling property issues. She got involved in legal disputes with the Austrian state over Edvard Munch's painting Summer Night on the Beach , which Walter Gropius had once given to her on the occasion of the birth of their daughter and which Carl Moll emigrated to the United States in April 1940 after Alma Mahler-Werfel today's Österreichische Galerie Belvedere . Alma Mahler-Werfel lost the trial because she could not credibly prove that her stepfather had done this without her consent. The proceeds from the sale of the picture were also used to carry out necessary repairs to her house on Semmering. There was no personal enrichment for Moll. Until the 1960s she tried to get the picture published and refused to step on Austrian soil again. The fact that Alma Mahler-Werfel had tried, through her brother-in-law, to sell Bruckner's handwritten score of the first three movements of his 3rd symphony to the Nazis at the end of the 1930s, was also discussed during the court hearing . The painting was only returned to Alma's granddaughter Marina Fistoulari-Mahler on May 9, 2007.

On her seventieth birthday, Alma Mahler-Werfel received an unusual gift that also documents how closely she was connected to the cultural scene. A couple of friends had written to acquaintances and friends of Alma Mahler-Werfel months before the birthday and asked them to design a piece of paper for each. The 77 well-wishers who conveyed their congratulations in this way included, among others, their former husband Walter Gropius , Oskar Kokoschka , Heinrich and Thomas Mann , Carl Zuckmayer , Franz Theodor Csokor , Lion Feuchtwanger , Fritz von Unruh , Willy Haas , Benjamin Britten , her former son-in-law Ernst Krenek , Darius Milhaud , Igor Stravinsky , Ernst Toch , the conductors Erich Kleiber , Eugene Ormandy , Fritz Stiedry , Leopold Stokowski and the former Austrian Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg . Arnold Schönberg , who had not been invited to participate in the book because of a previous quarrel with Alma Mahler-Werfel, dedicated a birthday canon to her with the text:

"The center of gravity of your own solar system, orbited by radiant satellites, this is how your life looks to the admirer."

The autobiography My Life

In 1951 Alma Mahler-Werfel moved to New York, where she bought four small condominiums in a house on the Upper East Side. She herself lived on the third floor and used one apartment as a living room and the second as a bedroom. The two apartments on the floor above were used by August Hess, Werfels' former valet, and her guests. For a long time she had been working on an autobiography based on her diaries. As a ghostwriter , she first supported Paul Frischauer , with whom she had already fallen out in 1947 when he complained about her numerous anti-Semitic abuses. She worked with EB Ashton in the 1950s . He too saw the need to censor their diaries because of their anti-Semitic statements and the numerous attacks on people who were still alive. In 1958, And the Bridge Is Love was published in English .

The reactions to this English edition were subdued. In particular, Walter Gropius reacted hurtfully to the portrayal of their early love affair and marriage. The reactions of other friends and acquaintances, such as Paul Zsolnay , made it clear to Alma Mahler-Werfel that a German-language edition that had already been considered would have to be changed accordingly. Willy Haas was given the task of preparing the version for the German-speaking market and further smoothing out the original text. Her previous ghostwriters had already advised her to delete her racial statements. Only the reactions to the English edition made them rethink:

"Please let the whole Jewish question disappear into oblivion"

she wrote to Willy Haas.

The German-language publication Mein Leben did not find the positive reception it had expected. The book was considered "slippery", ambiguous, contradictory and, in its self-centered manner of presentation, attracted caricatures. Long-time companions like Carl Zuckmayer and Thomas Mann had already withdrawn from her after the English version was published. Zuckmayer wrote after her death:

"[She is to me], with all the fun that one could have in the colourfulness, colourfulness, talent for life, even in the unrestrainedness and violence of this nature, through this all too uninhibited memoir book (which, however, has something gigantic, namely tactlessness and falsifications, inherent), become quite repugnant ... "

The verdict of her biographer Astrid Seele is also sharp:

"Your autobiographical alleged identification with your role as a muse represents only a last desperate attempt to believe in your own personal lie and to justify your life to yourself."

death

Alma Mahler-Werfel died on December 11, 1964 at the age of 85 in her New York apartment. At the first funeral two days later, Soma Morgenstern gave the funeral oration . Mahler-Werfel was not buried until February 8, 1965 in Vienna at the Grinzing cemetery in the already existing grave (group 6, row 6, number 7) of her daughter Manon Gropius, who died in 1935. The honorary grave is not far from her first husband.

The obituaries that appeared after her death mostly related to her marriages and love affairs under the impression of her autobiography. The mixture of attraction, admiration and dislike that she aroused in many is also expressed in a poem that the songwriter and satirist Tom Lehrer wrote and published spontaneously after her death.

Friedrich Torberg's obituary for Alma Mahler-Werfel, which was published in 1964, explains more comprehensibly why so many cultural workers were fascinated by this woman:

“If she was convinced of someone's talent, she left no other path open for the owner - with an energy that often bordered on brutality - than that of fulfillment. He was obliged to do this to himself and her and to the world, and she felt it was a personal affront if a talent she recognized or even promoted was not generally recognized. Incidentally, this only happened to a few, and she remained touchingly loyal to them. She was beguiled by success, but not unsuccessful. Her enthusiasm, her dedication, her self-sacrifice knew no bounds and had to be fascinating and animating because she had nothing of uncritical idolatry about her, because her judgment could not be obscured by anything. "

“That was probably also the reason why so many creative men got stuck with her. Here their own productivity continued and around […]. She had a way of arranging and conducting which, with geometric inevitability, assigned her the center, and everyone was happy about it: because this center was fixed and staged the others, not itself […]. In the morning she used to get up at 6 o'clock, emptied a bottle of champagne and played the 'Well-Tempered Clavier' for an hour. I report that from experience. Because I had stayed true to my habit of doing the paperwork necessary to cover my livelihood at night, even in Los Angeles, and it was not uncommon for the telephone to go off at dawn, from which her voice could be heard without further formalities: 'You're still awake? Come have breakfast! ' And there was no contradiction. "

Reception of the songs by Alma Schindler-Mahler

Only seventeen songs are known of their entire oeuvre: of the approximately "hundred songs" mentioned on various occasions, fourteen were printed by various publishers between 1911 and 2000. These include the 5 songs published in January 1911 , composed between 1899 and 1901:

- The silent city , text by Richard Dehmel

- In my father's garden , text by Otto Erich Hartleben

- A mild summer night , text by Otto Julius Bierbaum ,

- With you it's daring , text by Rainer Maria Rilke

- I am walking among flowers , text by Heinrich Heine

In June 1915 Alma Schindler-Mahler published four songs that she had composed in 1901 and 1911:

- Light in the night , text by Otto Julius Bierbaum

- Forest bliss , text by Richard Dehmel

- Rush , text by Richard Dehmel

- Singing in the morning , text by Gustav Falke .

In April 1924, Alma Maria Mahler published five more of her songs as five songs with Josef Weinberger :

- Hymn , text by Novalis - probably composed in the early 1920s

- Ecstasy , text by Otto Julius Bierbaum - composed on March 24, 1901

- The Knowing One , text by Franz Werfel - composed in October 1915

- Hymn of Praise , text by Richard Dehmel - composed on June 16, 1900

- Hymn to the Night , text by Novalis - probably early 1920s

According to Knud Martner , No. 1, Hymn or Hymn , and No. 4 Lobgesang were orchestrated by Paul von Klenau in 1924 ; the scores were discovered in 2019 in the Klenau estate of the Royal Library in Copenhagen.

- First performance of the three chants with orchestra: September 22, 1924 in Vienna (Musikverein). Soloist: Laurenz Hofer, Conductor: Leopold Reichwein .

- Further performance: February 17, 1929, Wiener Rundfunk. Soloist: Anton Maria Topitz, conductor: Rudolf Nilius . On this occasion, Alma Mahler was interviewed on the radio.

In 2000, two posthumous (previously lost) songs were published, edited by Susan M. Filler, Hildegard Publishing Company, Bryn Mawr, USA:

- Do you know my nights , text by Leo Greiner

- A first blossom is blowing softly , text by Rainer Maria Rilke

In 2018, Barry Millington published in London ( The Wagner Journal ):

- Lonely walk , text by Leo Greiner

Reception history

Alma in works by other composers

- The Adagietto in Mahler's Symphony No. 5 is, according to the conductor Willem Mengelberg a love letter to Alma.

- In 1906, Gustav Mahler attempted to musically portray Alma in the 6th Symphony . Alma gives the following information about this: “After he had drafted the first sentence, Mahler came down from the forest and said: 'I tried to hold you on a topic - I don't know whether I succeeded. You have to put up with it. ' It is the big, lively theme of the first movement. "

- Gustav Mahler's 8th Symphony is dedicated to his wife Alma. The first performance of the symphony fell at the time of a serious marital crisis. Mahler tried to win his wife back over with the greatest expressions of love, including the dedication of the 8th Symphony.

- The marriage crisis of 1910 is reflected in Gustav Mahler's 10th Symphony . The manuscript shows an abundance of intimate entries that document that Mahler was going through the worst existential crisis of his life at the time. The deeply moving exclamations indicate that the addressee of these entries was Alma: “You alone know what it means. Oh! Oh! Oh! Goodbye my string game! Goodbye, goodbye. Farewell. ”(At the end of the fourth sentence) -“ Live for you! Die for you! Almschi! ”(At the end of the finale). Alma later made the sketches available to her guests in a showcase in her apartment, which Elias Canetti oppressively described as a “memorial chapel”.

- Gustav Mahler's song Liebst Du um Schönheit (1902), the setting of a Rückert poem, is a “private dissimum” to Alma.

- Alexander Zemlinsky's Five Songs, Op. 7 , 1899 are dedicated to Alma. It is also referred to in reference to Zemlinsky's opera “Der Zwerg” (1922), after Oscar Wilde's fairy tale The Birthday of the Infanta , in which a beautiful princess receives an ugly dwarf as a birthday present who has never seen himself in the mirror. The gnome falls in love with her and thinks he will meet with love after the princess tosses him a rose as a joke. In the end, he is informed about the evil game, recognizes its ugliness in the mirror - and dies. This can easily be seen as a paraphrase of the relationship between Alma and Zemlisky. Zemlinsky's seven-part “Lyric Symphony” based on texts by Rabindranath Tagore is also a reflection of his unhappy love for Alma. Zemlinsky was inspired for this lied symphony by Gustav Mahler's " Das Lied von der Erde " and refused to have his work premiered together with Mahler's unfinished 10th symphony, which was his reaction to Alma's affair with Walter Gropius .

- Hans Pfitzner dedicated his string quartet in D major op. 13 to Alma (1902/03, premiered 1903 in Vienna).

- In 1923 Ernst Krenek composed Orpheus and Eurydike , an opera in three acts op.21 (premiered in 1926), based on a libretto by Oskar Kokoschka , where Orpheus stands for Kokoschka himself, Eurydice for Alma, Psyche for her daughter Anna Mahler and Pluto , the god the underworld, for Gustav Mahler.

- Alban Berg dedicated his opera Wozzeck (1915–1921, premiered 1925) to Alma , out of gratitude for the diverse (including financial) support of his work.

- In memory of Alma's daughter Manon Gropius , Alban Berg composed his violin concerto in 1935 and dedicated it to “the memory of an angel”.

- Erich Wolfgang Korngold's Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D major op. 35 from 1945 is dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel, who was a long-time friend of the family and was one of the artists in exile in California.

- Arnold Schönberg dedicated a four-part canon to Alma Mahler-Werfel for his 70th birthday on August 31, 1949.

- Benjamin Britten dedicated his Nocturne, Op. 1958 to Alma Mahler in recognition of what he owed Gustav Mahler . 60 (for tenor, seven obbligato instruments, and string orchestra) . It premiered at the Leeds Centenary Festival the same year it was made.

- In 1965 Tom Lehrer published the ballad "Alma", a satirical contribution to their relationship-rich life. (see: web links)

Alma at Oskar Kokoschka's work

- Alma Mahler, 1912, oil on canvas, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

- In the first days of their acquaintance, Kokoschka had Alma pose as the new Gioconda and gave her features like Leonardo to his Mona Lisa . Alma saw herself in this portrait as Lucrezia Borgia .

- Alma Mahler and Oskar Kokoschka, 1913, charcoal and white chalk, Leopold Museum , Vienna

- Double portrait of Oskar Kokoschka and Alma Mahler, 1912/1913, oil on canvas, Folkwang Museum , Essen

- Seven fans for Alma Mahler, 1912/1913, Indian ink and watercolor on untanned goat skin, Museum of Arts and Crafts , Hamburg

- Kokoschka described the seven compartments that he gave Alma between 1912 and 1914 as "love letters in imagery". The first fan was created on Alma Mahler's birthday in 1912. The third fan illustrated the trip to Italy together in 1913 and formed the basis for the later painting “The Bride of the Wind”. Only six compartments have survived; Alma’s husband Walter Gropius threw one into the fire out of jealousy.

- The Bride of the Wind, 1913, oil on canvas, Kunstmuseum Basel , Basel

- The painting was first called “ Tristan und Isolde ”, the title of Richard Wagner's opera that accompanied the two's first meeting. When Kokoschka painted the picture, the Austrian poet Georg Trakl was around him almost every day and gave the painting his name: “The fires of the peoples around you are golden. The glowing bride of the wind, the blue wave of the glacier, and the bell in the valley rumbles violently over black cliffs, drunk with death: Flames, curses and the dark games of lust storm the sky a petrified head. "

- Fresco for Alma Mahler's house in Breitenstein, 1913

- Before Alma moved into her new house in Breitenstein am Semmering in December 1913, Kokoschka painted a four-meter-wide fresco over the fireplace, as a continuation of the flames and Alma how she “points to heaven in ghostly brightness while he stands in hell Death and snakes seemed to be overgrown. ”The fresco was long thought to be lost and was only rediscovered in 1988.

- Alma Mahler, 1913, chalk, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art , Edinburgh

- Alma Mahler with Child and Death, 1913, chalk, Essl Collection , Klosterneuburg

- Kokoschka shows Alma with the fetus of a child, alluding to the painful abortion in October 1912.

- Alma Mahler spins with Kokoschka's bowels, 1913, chalk, Essl Klosterneuburg collection

- Kokoschka illustrates the pain Alma inflicted on him as a result of the abortion. He uses the “torture of St. Erasmus von Formio ”, exchanging the winch for a spinning wheel on which Alma winds the intestines that are bulging out of his stomach.

- Alma Mahler besieged by admirers, 1913, lithograph , Albertina Graphic Collection , Vienna

- Alma is harassed in a sacred room by six admirers (including the composer Hans Pfitzner ) and seems to enjoy it.

- Allos Makar, 1913, lithography cycle (5 sheets)

- From the letters of the names Alma and Oskar, Kokoschka formed the title of a poem Allos Makar (Greek for "Different is happy"), which he illustrated with this graphic cycle.

- Still life with putto and rabbit, 1914

- In the picture Kokoschka depicts the breakup of his love affair with Alma in a parable: “One must not intentionally prevent the development of a human life out of nonchalance. It was also an intervention in my development, that makes sense. ”With the intervention that Kokoschka mentions here, he is addressing the child that Alma was expecting and who she had aborted in 1914.

Oskar Kokoschka's life and work were shaped by this relationship for a long time even after the love affair with Alma Mahler ended. His drama Orpheus und Eurydice , which he completed in 1918, reflects the failure of his love for Alma Mahler in the myth of this ancient love story. It was set to music by Alma's son-in-law Ernst Krenek .

One of the more bizarre anecdotes in art history is that at the end of 1918 Kokoschka had the doll maker Hermine Moos make a life-size doll fetish based on Alma's model. Kokoschka wrote instructions for use for the doll maker in numerous letters, for example: "I am very curious about the padding, on my drawing I have indicated the areas that are important to me, the pits and wrinkles that are important to me, through the skin - on their invention and material, The different expressions corresponding to the character of the body parts I am really very excited - will everything get richer, more tender, more human? ”When the doll arrived at Kokoschka's in Dresden, the disappointment was great, he tried in vain to try his beloved in the object made of fabric and wood wool Recognize Alma. He immortalized “The silent woman”, as the unsuccessful copy was now called, in numerous ink drawings and paintings. He dressed them in expensive costumes and lingerie from the best Parisian fashion salons and let the rumor spread through his chambermaid that he had hired a carriage “to take them outside on sunny days and a box in the opera to show them off. “Kokoschka finally destroyed this fetish himself by pouring wine over the doll after a night of partying and chopping off her head. That earned him a visit from the police, as neighbors thought the parts of the doll lying in the garden were a corpse .

- Standing female nude - Alma Mahler, 1918

- This life-size nude sketch of Alma Mahler was made by Kokoschka as a template for the Alma doll for Hermine Moos.

- The Doll Fetish with Cat, 1919, Green Chalk, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum , New York

- Woman in Blue, 1919

- The painting shows the doll, has been revised several times and prepared in around twenty studies.