Lucrezia Borgia

Lucrezia Borgia [ luˈkrɛtːsi̯a ˈbɔrdʒa ] ( lat. Lucretia Borgia; Spanish / Cat. Lucrecia Borja; born April 18, 1480 in Rome or Subiaco ; † June 24, 1519 in Belriguardo near Ferrara ) was an Italian-Spanish Renaissance princess and the illegitimate Daughter of Pope Alexander VI. with his lover Vanozza de 'Cattanei . She was the sister of Cesare , Juan and Jofré Borgia .

Lucrezia, described by contemporaries as pretty and fun-loving, became a beneficiary after the rise of her infamous family, but above all an instrument of her father's politics.

Alexander VI, who loved her more than anything, gave her the affairs of state in the Vatican several times during his absence . He married them three times in politically motivated marriages to consolidate the power of the Borgia . Lucrezia's first marriage to Giovanni Sforza was dissolved when she lost her use for the Borgia, her second husband, Alfonso of Aragon (1481–1500), Duke of Bisceglie , was probably murdered on the orders of her brother Cesare. In her third marriage, she finally married Alfonso d'Este , Duke of Ferrara , with whom she remained married until her death and had several children.

Lucrezia survived the death of her father and the fall of her brother Cesare and the Borgia family in Italy unscathed, she died, highly honored, as Duchess of Ferrara .

The Borgia family still embodies the lust for power and moral corruption of the papacy of the Renaissance like no other , and Lucrezia Borgia maintained for centuries the reputation of a wicked poisoner, adulteress and blood molester with her father and her brother Cesare. These allegations had their origin in the rumors and defamations of their own time and were later taken up and reinforced in their works by famous authors such as Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas . Only modern historical research sees Lucrezia Borgia in a different light and rejects these accusations.

origin

Lucrezia Borgia was born on April 18, 1480, the third of four children of the Spanish Cardinal and Vice Chancellor of the Church, Rodrigo Borgia , later Pope Alexander VI, and his long-time Italian lover Vanozza de 'Cattanei . She was probably born in Subiaco, a fortress of her father outside Rome, because her father initially wanted to keep the existence of his illegitimate family a secret out of consideration for his church career. Illegitimate children were common among clerics at the time, but were mostly passed off as nephews and nieces. Rodrigo Borgia therefore caused a scandal after his election as Pope when he openly confessed to his children, who thus became known throughout Europe. Lucrezia and her brother Cesare in particular achieved a notorious reputation that continues to this day.

Life

Early years

Lucrezia Borgia probably spent her early childhood in her mother's house in Piazza Pizzo di Merlo and was at least partially taught by nuns in the Dominican convent of San Sisto. She received the typical training of a high-ranking lady of her time, which included humanistic literature, eloquence, and dancing. In addition to Italian and the Catalan spoken within the Borgia family , she mastered French and Latin (she wrote poems in these languages, among other things) and understood Greek. When she died, her library included works from Francesco Petrarca to Dante Alighieri . She also loved music and poetry all her life and later worked as a patron for artists and poets.

Before she was twelve, her father placed her in the care of his relatives Adriana de Mila, who was married to Ludovico Orsini , a daughter of Rodrigo Borgia's cousin Pedro de Milà, whom Lucrezia referred to as "my mother" in a letter as an adult. Her relationship with her mother Vanozza remained distant from then on, but she was very close to her father. Rodrigo Borgia, who next to her and her brothers already had three children and would later father more, especially loved Lucrezia according to the chroniclers "extremely". Of her siblings, she was closest to her brother Cesare; she was later accused of incest with both him and her father.

Engagement to Don Cherubin Juan de Centelles and Don Gasparo da Procida e Anversa

As with all noble girls of her time, Lucrezia was expected to enter into a marriage that was politically advantageous for her family at an early age. When Lucrezia was eleven, her father became engaged to Don Querubi de Centelles (Don Cherubin Juan de Centelles), lord of Val d'Ayora in the Kingdom of Valencia. He was the son of the Count of Oliva and a member of an old Spanish noble family. The contracts, drawn up in Catalan, were sealed on February 26, 1491 by the notary Beneimbene and Lucrezia opened on June 16, 1491. In the contract, a dowry of 300,000 timbres or sous of Valencian coin was agreed for Lucrezia.

This sum of money should be paid out in the form of cash, jewels and other trousseau. Eleven thousand timbres should come from the legacy of her older half-brother Pedro Luis Borgia; eight thousand timbres were to be a gift from their older brothers Cesare and Juan, which was probably also part of the inheritance of the first Duke of Gandia. Lucrezia's procurator during the negotiation of the marriage contract was the Roman Antonio Porcaro. It was agreed that Lucrezia would be brought to Valencia at the Cardinal's expense within one year of the signing of the marriage contract and that the church wedding would be consummated within six months of her arrival in Spain.

This engagement was soon canceled and the now twelve-year-old Lucrezia was finally betrothed to Don Gasparo da Procida e Anversa , son of the knight Count Gian Francesco von Aversa and his wife Donna Leonora von Procida and Castelleta, after the marriage contract was confirmed in April 1492 . In the log book of the notary Beneimbene of November 9, 1492, it was recorded in writing that the marriage engagement between Lucrezia and Gasparo had been carried out on April 30, 1491 by procuration and that Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia had undertaken to send his daughter to the city of Valencia free of charge. Jofré Borgia, Baron of Villa Longa, Canon Jacopo Serra of Valencia and the Valencian Vicar General Mateo Cucia are named as procurators for this legal act. Lucrezia was thus engaged to two men for a while. During the papal election, which took place after the death of Pope Innocent VIII on July 25, 1492, Lucrezia was in Rome with her brother Jofré in the house of Adriana de Mila. After her father was elected Pope on August 11, he had Lucrezia, Adriana de Mila and their young daughter-in-law, his new lover Giulia Farnese , housed in the Palazzo Santa Maria in Portico near the Vatican. Lucrezia thus moved into the public eye and above all into the focus of the mostly hostile Borgia chroniclers and the envoys of the various Italian and European principalities at the papal court. The envoy Niccolò Cagnolo from Parma described Lucrezia's appearance:

“She is of medium size and graceful, her face is rather long, her nose is nicely cut, her hair is golden, her eyes are not a particular color, her mouth is quite large, her teeth are brilliant white, her neck is slim and beautiful , her bosom shaped admirably. She is always happy and smiling. "

Marriage to Giovanni Sforza

After his election as Pope, Lucrezia's father also canceled this connection in order to marry her even more cheaply. Ascanio Sforza had significantly supported the election of Rodrigo Borgia as Pope and received the city of Nepi , the office of Vice Chancellor and the Borgia Palace, which today still bears the name Sforza-Cesarini. As the now most influential cardinal and confidante of Alexander VI. namely, he operated the marriage of Lucrezias with a member of his house, Giovanni Sforza , Count of Cotignola and ecclesiastical vicar of Pesaro . He was the illegitimate son of Costanzo I Sforza and Fiora Boni, his father's lover, and only by the grace of Pope Sixtus IV and Pope Innocent VIII he was his father's successor. Since the death of his first wife Maddalena Gonzaga, a daughter of Federico I Gonzaga , Margrave of Mantua , and his wife Margaret of Bavaria , on January 8, 1490, he was a widower. On October 31, 1492, after staying in Pesaro and Nepi, he secretly arrived in Rome and lived there in the apartment of the Cardinal of San Clemente. The young Count Gasparo had already come to Rome with his father and demanded that the contract be honored. On November 5, 1492, the envoy of Ferraras wrote to his master about the dispute between the two applicants for Lucrezia's hand:

“There is a lot of talk about this Pesaro's wedding; the first bridegroom is still there and he does a lot of bravado as a Catalan, assuring that he will bring a lawsuit before all princes and potentates of Christianity; but willing or not, he will have to be patient. "

On November 9, 1492, the same Ferraras envoy provided further details on the public scandal that was the subject of discussion in Rome:

“Heaven grant that this marriage will not cause any harm to Pesaro. It seems that the King (of Naples) is dissatisfied with inferring from what Giacomo, Pontano's nephew, said to the Pope the day before yesterday. The matter is still pending; Both parts are given good words, namely the first and the second betrothed. Both are here. However, it is believed that Pesaro will assert the field, especially since Cardinal Ascanio is leading his cause, and he is powerful in words and deeds. "

On November 8, 1492, the marriage contract between Lucrezia and Don Gasparo was legally dissolved. Don Gasparo and his father were still hoping to get married under better conditions and the young count therefore undertook not to marry again before a year. On December 9, 1492, the Mantuan agent Fioravante Brognolo wrote to the Marchese Gonzaga:

“The matter of the illustrious Mr Giovanni of Pesaro is still pending; It seems to me that the Spanish nobleman, to whom the niece of Sr. Holiness was promised, does not want to withstand her; he also has a large following in Spain, so the Pope first wants to let this deal mature before he concludes the same. "

In February 1493 there was talk of a planned connection between Lucrezia and the Spanish Conde de Prada. Giovanni Sforza stayed in Pesaro during the negotiations and sent his procurator Nicolò de Savano to Rome to finalize the marriage contract. Pope Alexander VI finally, according to the chronicler Burchard, paid the Count of Aversa a sum of 3,000 ducats to appease the family. The dissolution of the marriage contract does not seem to have further strained the relationship between the Borgia and the Centelles family, as members of the Centelles family such as Gulielmus de Centelles and Raymondo de Centelles as protonotaries and treasurers of Perugia can be found in the Pope's later entourage. The marriage was carried out on February 2, 1493 in the Vatican by a judicial instrument, with Juan Lopez, Juan Casanova, Pedro Caranza and Juan Marades also witnessing this marital union in addition to the ambassador of Milan. The bride received a dowry of thirty-one thousand ducats, and it was agreed that she would travel to Pesaro with her husband by the end of the year. On April 23, 1493, the marriage contract was signed, which regulated the marriage between Lucrezia and Giovanni Sforza. Giovanni Sforza moved through the Porta del Popolo in Rome on June 9, 1493, where he was expected by Lucrezia in a dress made of sky-blue brocade and Giulia Farnese in the Palazzo near Santa Maria di Portico. On June 12, 1493, Lucrezia married Giovanni Sforza , Count of Pesaro and cousin Ludovico Sforzas , the ruler of Milan, and thus became Countess of Pesaro . At that time, the principality comprised the city of Pesaro and a number of smaller communities called castles or villas. These smaller parishes were S. Angelo in Lizzola, Candelara, Montebaroccio, Tomba di Pesaro, Montelabbate, Gradara, Monte S. Maria, Novilara, Fiorenzuo, Castel di Mezzo, Ginestreto, Gabicce, Monteciccardo, Monte Gaudio and Fossombrone. Pesaro was part of the Papal States and the Sforzas held the title of vicars to inherit against the payment of 750 gold guilders annual interest. Her father had entered into a political alliance with the Sforzas through this marriage. The couple lived separately at first because the consummation of the marriage had been postponed due to the bride's youth. While Lucrezia now resided and held court in the Palazzo Santa Maria in Portico, Giovanni Sforza stayed in Pesaro. Since Giovanni Sforza had borne himself financially through the wedding celebrations, he turned to his father-in-law at the Vatican and asked for part of the dowry, but was refused to pay it. After the outbreak of an epidemic in Rome in the early summer of 1494, Giovanni Sforza, Lucrezia, their mother Vannozza, Giulia Farnese and Adriana di Mila traveled to Pesaro, where they moved in on June 9, 1494 and lodged in the Sforza palace. In the summer of 1494, Lucrezia moved into the Villa Imperiale on Monte Accio.

In 1494, the French King Charles VIII undertook a campaign to Italy to enforce his Anjou claim to the Kingdom of Naples. To this end, he allied himself with Ludovico Sforza , Duke of Milan. The French, led by Charles VIII, advanced to Italy with a well-equipped army with many German and Swiss mercenaries. On March 31, 1495, the other Italian states allied under the leadership of Venice against France and Milan. They pretended to take action against the Turks, but their main aim was to destroy the Milanese and French forces. In 1495, Giovanni Sforza found himself in a very difficult political situation due to the marital alliance with the Borgia on the one hand and the family ties to the Sforzas on the other. As a condottiere in the service of the Pope, he joined the Neapolitan army, which was supposed to fight the French, and at the same time he acted as a spy for Ludovico il Moro in Milan, who had allied himself with the French. After a year in Pesaro, Lucrezia returned to Rome via Perugia, where she met her father. While Lucrezia was again living in her palace, her husband was traveling with troops in the Naples area. On May 20, 1496, Jofré Borgia and his wife Sancia came to Rome. Sancia and Lucrezia soon became friends and also caused a public scandal when they did not take a seat in the choir stalls, which were only intended for prelates and canons, in accordance with the protocol during the main service in St. Peter. Since the Borgia and the Sforza continued to occupy different positions with regard to Charles' conquest in Naples and the dual role of Giovanni Sforza in this war had been discovered in the spring of 1497 at the latest, violent arguments between Juan Borgia and his brother-in-law arose in March 1497. Giovanni Sforza left Rome in secret on Good Friday. On the morning of Good Friday, March 1497, he is said to have entered his wife's chamber and told her that on the occasion of the high church day he wanted to go to confession either in a church in Trastevere or in a church on the Janiculum. Afterwards, he still intends to undertake the traditional pilgrimage to the “Seven Churches” in Rome, which, as usual, would take the whole day. Immediately after saying goodbye to his wife, he rode his Arabian horse to Pesaro so quickly that the horse collapsed dead after his arrival that evening.

According to a chronicle of Pesaro, Lucrezia is said to have hidden a servant of her husband in her room when Cesare visited her to talk to her about the murder of the count. In any case, Giovanni had left two messages before he fled, one to Lucrezia, asking him to follow him to Pesaro, and one to the Milanese ambassador, in which he explained to his Milanese relatives that he had fled out of “dissatisfaction with the Pope”. Pope Alexander VI immediately requested that Lucrezia's marriage to Giovanni Sforza be dissolved. At the beginning of July 1497, Lucrezia sought refuge and tranquility in the Dominican convent of San Sisto. Lucrezia spent the time involved in the lengthy negotiations to annul the marriage in this monastery. Most likely, the escape to Pesaro saved Giovanni Sforza's life and forced the Borgia to dissolve the marriage by legal means. According to church law, the declaration of nullity of marriage was only possible by declaring the marriage to have not been legally valid or not to have been consummated. Although the Borgia left the husband to choose the reason for dissolution, Giovanni Sforza initially did not give his consent to dissolve the marriage. Alexander now formed a commission to examine whether the marriage could be dissolved for failure to execute. The commission set up by the Pope finally came to the conclusion that the marriage had not been consummated because of the impotence of the husband. So Alexander declared the marriage invalid. Her husband Giovanni Sforza, divorced on December 20, 1497 because of alleged impotence, claimed at the time that his marriage had only been dissolved so that her father and brother Cesare Borgia could indulge in incest with Lucrezia undisturbed . Giovanni Sforza created the basis for those suspicions that still cling to Lucrezia and her family today. Allegedly Giovanni Borgia , called infans romanus , who was born at this time and is mentioned in two bulls once as the son of Alexander and once as the son of Cesare, is said to have sprung from this connection. According to another theory, the child comes from an affair Lucrezia with Perotto (also Pedro Caldés), the messenger of her father. The young Spaniard served as an intermediary between the Pope and his daughter during their stay at the San Sisto Monastery. On February 14, 1498, the dead bodies of the servant Pedro Calderon and the maid Penthesilea were found in the Tiber. On March 18, 1498, the envoy to Ferraras reported that Lucrezia had had a child in the monastery of San Sisto. Although this was denied by the Borgias, it has not yet been possible to refute that this child was possibly Giovanni Borgia.

Marriage to Alfonso Bisceglie

Her second husband, Don Alfonso of Aragon, Duke of Bisceglie and Prince of Salerno, was an illegitimate son of King Alfonso II of Naples from his relationship with Trusia Gazullo (or Truzia Gazella). He was thus a nephew of King Federigo of Naples from the House of Trastámara . This marriage was intended to consolidate the Borgias' connection to Naples and Spain after Lucrezia's brother Jofré had married Alfonso's sister Sancha of Aragon four years earlier in 1494 . On June 20, 1498, the marriage contract was signed in the Vatican in the absence of both spouses. After the actual wedding ceremony on July 21, 1498, the couple stayed in Rome and lived in the Palazzo of Lucrezia. Alexander VI. appointed his daughter ruler of Spoleto and Foligno and announced this to the cities on August 8, 1499. Later he also appointed her ruler of Nepi , but shortly afterwards Lucrezia returned with her husband to Rome and gave birth to their son Rodrigo, who later became Duke of Bisceglie , on November 1, 1499 at six in the morning . On November 11th, 1499, the feast of St. Martin, the baby was solemnly baptized in the Chapel of Sixtus in St. Peter by Cardinal Carafa. All the cardinals present in Rome took part. Since the Pope and Cesare Borgia had in the meantime allied themselves with the French against Spain and Naples, serious conflicts arose with the son-in-law and brother-in-law. Alfonso was attacked in St. Peter's Square on July 15, 1500 at eleven o'clock in the morning on the way from the Vatican to the Palazzo Santa Maria in Portico, where he and Lucrezia lived, and was seriously wounded in the head, right arm and thigh with dagger stabs. The heavily armed attackers had been waiting for their victims in St. Peter's Square disguised as pilgrims. Alfonso, who as a prince from the House of Aragon had received excellent weapons training, was able to save himself wounded in the Vatican despite the superior strength of the men. The bandits managed to escape, and so the masterminds behind this attack could never be identified. Alexander VI. immediately had the seriously injured son-in-law put up in a room directly above the papal apartments and treated by his own doctors. Alfonso, however, refused any medical help for fear of poison and had the King of Naples informed by a courier that he was in extreme danger, whereupon he immediately sent his personal physician to Rome. Also by order of Alexander, the rooms were even guarded by the papal guard. Lucrezia and her sister-in-law Sancia cared for Alfonso until he was murdered on August 18, 1500 by Michelotto on behalf of Cesare or the Pope himself. There are different versions of the sequence of events. The most likely description is that a troop of armed men led by Cesare's captain Michelotto Corella entered the papal apartments and arrested the doctors. When Lucrezia and Sancia oppose them, Michelotto is said to have declared that he was only carrying out an order, but that if the Pope ordered otherwise, he would of course be ready to obey it. Lucrezia and Sancia followed Michelotto's advice and then left the room to see their father and overturn the warrant. What Alexander ordered is unknown and has no bearing on the fate of the Duke of Bisceglie. Michelotto did not think of waiting for the two women to return, and so on their return Lucrezia and Sancia found Alfonso strangled. A certain Brandolin described the harrowing scene, which was confirmed by other eyewitnesses:

“On the advice of the doctors, the wounds were bandaged, the patient (Alfonso) no longer had a fever or at least very little and was joking in the bedroom with his wife and sister when suddenly ... Michelotto (Miguel da Corella), the weird one Servant Cesare Valentinos (Lucrezia's brother) entered the room. He grabbed Alfonso's uncle and the royal ambassador (Naples) by force, and after binding their hands behind their backs, he handed them to two armed men standing behind the door to lead them to the dungeon. Lucrezia, Alfonso's wife, and Sancia, his sister, surprised by the suddenness and violence of what had happened, shouted at Michelotto and asked how he could dare to commit such an iniquity in front of their eyes and in the presence of Alfonso. He apologized as eloquently as he could and declared that he was only obeying the will of others, that he had to live by the orders of others, but if they wanted they could go to the Pope and it would be easy to obtain the release of those arrested . Overwhelmed with anger and compassion ... the two women went to the Pope and insisted that he hand over the prisoners to them. Meanwhile, Michelotto, the most villainous of all criminals and most criminal of all villains, strangled Alfonso, who had indignantly reprimanded him for his wrongdoing. When the women returned from the Pope, they found armed men in front of the room door who denied them entry and reported that Alfonso was dead. Michelotto, the author of the crime, invented the story, neither true nor half-true, that Alfonso, disconcerted by the magnitude of the danger in which he was in, had seen how to meet men who were related to him by kinship and benevolence , torn from his side, passed out and that a lot of blood flowed from the wound in his head and that he died that way. The women, appalled by this cruel act, depressed with fear and beside themselves with grief, filled the palace with their screams, wailing and lamenting, and one called for her husband, the other for her brother, and her tears did not end ... "

Johannes Burchard confirmed Brandolin's description and used the following meaningful sentence: Since Alfonso "refused to succumb to his wounds, he was strangled at four in the afternoon." Six hours after the murder of Alfonso, his body was quietly brought to St. Chapel of Santa Maria delle Febbri buried in St. Peter. His murderer was allegedly Cesare Borgia, although in this case the Pope himself presumably gave the order to kill. On the day of his murder, Alfonso had shot Cesare, who was walking in the Vatican garden, with a crossbow from the window of his sickroom. Lucrezia then retired to her castle in Nepi, but came back to Rome a little later.

Marriage to Alfonso I. d'Este

In 1501, Alexander VI. to remarry. He first turned down the marriage offer from Francesco Orsini, Duke of Gravina, which the Orsini had offered. This time a marriage with Alfonso I d'Este of Ferrara was planned. He was the eldest son of Duke Ercole I d'Este of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio from his marriage to Eleonora of Aragón, the daughter of King Ferdinand I of Naples and his wife, Isabella di Chiaramonte. Lucrezia and Alfonso probably met for the first time in November 1492, when Ercole sent his son to Rome in the course of the celebrations for Alexander's election as Pope and he lived in the Vatican for a few weeks. At that time Alfonso was still married to Anna Maria Sforza, whom he married on January 12, 1491 or, according to other sources, on February 12, 1491 at the age of fifteen. She was the daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza and the younger sister of Bianca Maria Sforza . She died on November 30, 1497 as a result of a stillbirth and Alfonso was now a widower.

At first, Alfonso I, like his father Ercole I, was very averse. They considered it below their high standing to enter into conjugal relations with the Borgias. Lucrezia was also an illegitimate papal daughter. Alexander was able to blackmail the d'Estes in the face of the threat posed by Cesare Borgia in Romagna, as well as with a high dowry and other promises (favorable papal enfeoffments, financial benefits in the form of the waiver of tribute, cardinalate for the d'Este, etc.). After months of negotiations about the marriage contract and Ercole's high demands regarding the dowry, an agreement was finally reached. Ercole had requested a dowry from Lucrezia in the amount of 200,000 ducats and, as ecclesiastical vicar of Ferrara, demanded that church taxes be reduced from 4,000 to 100 ducats per year. He also wanted his third son Ippolito to be enfeoffed with the diocese of Ferrara. He also asked for the delivery of two small villages, Pieve and Cento, which had previously belonged to the diocese of Bologna. He also wanted to ensure that Lucrezia's dowry was paid to his envoy before the bride was allowed to enter Ferrara. Lucrezia finally received a dowry of 100,000 ducats in cash and 75,000 ducats in jewelry, clothing and valuables from her father. For this purpose Ferrara was granted financial advantages by the church, which also corresponded approximately to the sum of 100,000 ducats. The marriage contract was recorded on August 24, 1501. The Estonians countersigned the marriage contract drafted in the Vatican on August 26, 1501 and signed by the Pope on September 1, 1501 in their summer palace in Belfiore. When the marriage contract signed by Ercole and Alfonso returned to Rome on September 4, 1501, it was celebrated in Rome. Bombards were fired from Castel Sant'Angelo into the night and on the following day Lucrezia rode through Rome with an entourage of 300 horsemen. Bonfires were lit all over the city, and Alexander convened a consistory to brief the cardinals and ambassadors of the event. On December 13, 1501, the ambassador of the Marquis of Mantua reported:

“The dowry will total three times 100,000 ducats, not including the gifts that Madonna will receive on this or that day: first 100,000 ducats in cash and in Ferrara in installments; then silver items for more than 3,000 ducats, jewels, fine linen, valuable jewelry for mules and horses, in total for other 100,000. Among other things, she has a studded dress, more than 15,000 ducats in value and 200 precious shirts, some of which are worth 100 ducats. "

Another observer reported that because of Lucrezia's wedding in Naples, more gold was sold and processed in six months than in two years. In addition, Alexander Ercole had to transfer the castles Cento and Pieve and exempt him from all tax obligations towards the church. In the meantime, Lucrezia represented the affairs of the papacy in the Vatican from September 25, 1501 to October 17, 1501 as the deputy head of Christianity, as her father wanted to go on an inspection trip with Cesare to the newly acquired possessions of the Borgias near Rome. It was goods that Alexander had taken from the Colonna family. During this time, Lucrezia had the power to open all the Pope's correspondence. Burchard reports on this event:

“Before leaving Rome, he gave his rooms, the whole palace and the daily business to his daughter Lucrezia, who lived in the papal apartments during his absence. He also instructed her to open the letters addressed to him and, if there was any difficulty, she should seek advice from Cardinal Costa and the other cardinals, whom she could call upon for this purpose. For some reason Lucrezia sent to Costa and explained the Pope's mission to him. Costa considered the case insignificant and said to Lucrezia that if the Pope brought the matter to the Consistory, the Vice Chancellor or another cardinal would be there for him to keep the record; there must therefore also be someone there in a proper way to take note of the conversation. Lucrezia replied: I know how to write. Costa then asked: Where is your quill? Lucrezia understood the point of the cardinal's joke. She smiled and they both politely ended the conversation. I was not asked about these things. "

On October 31, 1501, Cesare gave a festive dinner in the Apostolic Palace , in which Lucrezia also took part and which went down in history under the name " Chestnut Banquet " or "Chestnut Ball". In this orgy, fifty invited courtesans danced naked with servants and other men after the meal, crawled around on the floor between burning candlesticks and picked up scattered chestnuts. The men who then performed the act most frequently with them were awarded prizes. This description of the chestnut banquet, which serious historians today do not assess as a factual report, comes from Johannes Burckard , master of ceremonies at the papal court.

Although Ercole had received a letter of protest from Maximilian against Alfonso's marriage to Lucrezia at the end of November 1501, on December 9, 1501, he sent the groom's escort, consisting of more than 500 people, to Rome from Ferrara to pick up the bride. The glamorous train arrived in Rome on December 23, 1501. In the meantime, the Borgias had spared no expense in Rome to impress the d'Este family with exaggerated splendor and costly festivities. At the city gate the procession was received by 19 cardinals and their entourage of 4,000 men. They moved from there to the Vatican, where Alexander and 12 other cardinals received the Ferrarese. On the same day the envoy visited Ferraras on behalf of his lord Lucrezia and made the following characterization of the papal daughter:

“My most illustrious lord. Today after dinner I went with Messer Girardo Sarazeno to the most illustrious Donna Lucrezia, to speak with her on behalf of Ew. Your Excellency and Sr. Glory to attend to Don Alfonso. On this occasion we had a long conversation about various things. In truth, she revealed herself to be very clever and amiable and of good nature, devoted to your Excellency and the illustrious Don Alfonso, so that one can judge that Your Highness and Don Alfonso will feel a real satisfaction with her. She also has a perfect grace in all things, along with modesty, loveliness and modesty. She is no less a believing Christian and shows herself to be godly. Tomorrow she wants to go to confession and then communicate on Christmas. Her beauty is already sufficiently great; but the courtesy of her manners and the graceful manner in which she behaves make her appear even greater: in short, her qualities seem to me of such a kind that one has nothing to suspect of her, but only justifies expecting the best actions is. I thought it appropriate, by writing this letter of mine, to testify to the truth according to Your Highness. "

This report is proof of the dubious reputation that Lucrezia must have enjoyed at the time of her marriage to Alfonso, and so the Ferraras ambassador in Rome had to reassure Ercole d'Este with that letter about his new daughter-in-law, since Lucrezia probably also with the alleged orgies of the Borgias had been present. On December 30, 1501, the wedding ceremony took place in the Vatican by procurationem. Alfonso's brother Ferrante, who accompanied the bridal procession with his brothers Cardinal Ippolito and Sigismund, served as the deputy of the absent husband. Johannes Burchard has described the wedding ceremony in detail:

“After the race on December 30th, the trumpeters and all kinds of musicians stood on the platform of the stairs of St. Peter and tuned all their instruments with great power. Donna Lucrezia stepped out of her apartment next to St. Peter's in a Spanish-style gold brocade robe with a long train that a maid carried after her. To her right went Don Ferdinand, to her left Don Sigismund, her husband's brothers. Then followed around 50 Roman ladies in splendid robes and behind them two and two servants of Lucrezia. They climbed up into the first Pauline Hall above the palace portal, where the Pope was with 13 cardinals and Cesare Borgia. The Bishop Porcario gave a sermon and the Pope repeatedly told him to speed up. When he was finally finished, a table was placed in front of the Pope. Don Ferdinand and Donna Lucrezia came up to the table before the Pope and Ferdinand lit a gold ring in the name of his brother Lucrezia. "

The jewelry given to Lucrezia was worth around 70,000 ducats. At the time of the handover, however, it was recorded in a certificate by Ercole's express order that Lucrezia had received the wedding ring as a gift. The rest of the jewelry was not mentioned in the deed of gift. Ercole wanted, as he openly admitted, to ensure that the Estonians would not lose the jewelry if the marriage had to be dissolved due to Lucrezia's infidelity. After the wedding, papal officials paid the people of Ercole the cash stipulated in the marriage contract as Lucrezia's dowry, because the Este did not want to take Lucrezia into Ferrara before the dowry was paid out. The handover of the dowry was delayed as a result of the discovery of counterfeit coins and so Lucrezia was only able to start her journey to Ferrara on January 6th. She left with her entourage of 180 people, which consisted of the Colonna, who had been disempowered by the Borgia, such as Francesco Colonna of Palestrina and his wife, and the Orsini, such as Fabio Orsini, as well as the members of the Houses of Farnese, Frangipani, Cesarini, Massimi and Mancini, Rome. She was accompanied by all the cardinals and MPs as far as the Porta del Popolo . At least 150 mules and numerous wagons were used to transport their magnificent trousseau. A Venetian observer even reported that their train consisted of a total of 660 horses and mules and 753 people, including the cooks, saddlers, cellar masters, tailors and the goldsmith of the papal daughter. A condition of the marriage contract was that she had to leave her son from her marriage to Alfonso von Aragon with her sister-in-law Sancha. Lucrezia and her entourage did not move into Ferrara until February 2nd and was received by her sister-in-law Isabella d'Este , Margravine of Mantua, among others . Alfonso was regarded as an expert in everything military, especially gun casting, and in all ballistic issues. He enjoyed himself with mistresses and prostitutes during the day, but regularly spent the night with her. After the death of Pope Alexander VI. on August 18, 1503, the French King Louis XII advised. Ercole I. and Alfonso for divorce. He wrote to the envoy from Ferrara:

“I know that they never agreed to this marriage. This Madonna Lucrezia is not really Don Alfonso's wife. "

Alfonso and the population of Ferrara refused to dissolve the marriage, although Ercole I wrote to his envoy Giangiorgio Seregni in Milan, then France:

“Giangiorgio. In order to enlighten you about what you are asked by many, namely whether the death of the Pope causes us grief, We give you to know that he is in no way unpopular with us. Rather, for the glory of God our Lord, and for the general good of Christianity, We have wished earlier that God's goodness and providence would provide for a good and exemplary Shepherd and that such a great scandal would be removed from his church. As for us in particular, we cannot wish otherwise; for the consideration of the glory of God and the common good will be decisive with us. But we also tell you that there has never been a Pope from whom We have received fewer favors than from him, even after the kinship we have closed with him. Only in need did We get from him what he was obliged to do. But he did not please Us in any other big or small matter. We believe that this is largely due to the Duke of Romagna; for, because he could not deal with Us as he was supposed to do, he treated Us like a stranger; he was never frank to Us, he never told Us his plans, nor did We tell him ours. Lastly, since he leaned toward Spain while We remained good French, We had nothing kind to hope for either from the Pope or from Sr. Glory. That is why this death did not grieve Us, because We had to expect nothing but evil of the size of the aforementioned Mr. Duke. We want you to convey this Our confidential confession verbatim to the Lord Grand Master (Chaumont), from whom We do not want to hide our feelings; but speak of it to others with caution, and then send this letter back to the venerable Mr. Gian Luca, our council, Belriguardo on August 24, 1503. "

In 1505, after the death of his father on January 25, 1505, Alfonso became Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio . Lucrezia became Duchess of Ferrara . As a patron of the arts, she gathered the most famous artists, writers and scholars of the time such as Pietro Bembo , Ludovico Ariosto , Mario Equicola , Gian Giorgio Trissino and Filippo Strozzi at the court of Ferrara . The famous rose poem by the poet Strozzi has been preserved:

“Rose, sprouted from the earth, plucked from the finger. Why does your colored shine appear more beautiful than usual? Does Venus color you again? Did Lucrezia's lip kiss you so sweetly shimmering purple? "

After the death of Alexander VI. In 1503 and a series of accidents in the d´Este family, however, she withdrew more and more and devoted herself to religious life. She spent a lot of time in monasteries, giving them financial support as well as the hospitals of the duchy. As regent of Ferrara, she gained great recognition and was entrusted with state affairs by her husband. So in May 1506 she passed a law that was supposed to ensure the protection of the Jews in Ferrara and a punishment of the guilty. After the poet Strozzi married Barbara Torelli, the widow of Ercole Bentivoglio, in May 1508, he was found dead on June 6, 1508 on the corner of the Este Palace, now called Pareschi. He was still wrapped in his cloak and his body was covered with twenty-two wounds. The murderers could not be identified. Lucrezia's eldest son from their second marriage died in August 1512. The Mantuan agent Stazio Gadio wrote on August 28, 1512 to his master Gonzaga from Rome:

"Here certain news has arrived that the Duke of Biseglia, the son of the Duchess of Ferrara and Alfonso of Aragon, died in Bari, where the Duchess of Bari had him with her."

When Lucrezia gave a reception to the leaders of the French passing through Ferrara before the Battle of Ravenna in 1512, the biographer of the famous Bayard wrote of Lucrezia:

“Before anyone else, the French received the good Duchess, who was a pearl in this world, with great honor, and every day she gave them wonderful Italian-style celebrations and banquets. I dare to say that it was neither in her time nor before there was a more glorious princess than she; for she was beautiful and good, gentle and kind to everyone, and nothing is more certain than this, that although her husband was a wise and bold prince, this lady did him good and great service through her kindness. "

During her marriage to Alfonso, she gave birth to eight children, four of whom reached adulthood. On September 5, 1502, their first daughter was born still. Three years later, in 1505, Alessandro was born, but he died that same year. Her two subsequent sons were granted a longer life. Ercole II. D'Este was born on April 4, 1508. In 1528 he married Renée de France, who was a daughter of the French King Louis XII. was. After the death of his father, Ercole II was made duke in 1534 and died in 1559. On August 25, 1509, Ippolito II. D'Este saw the light of day and became a respected clergyman. He was appointed cardinal in 1538 and was also a candidate in the papal elections several times, but he never succeeded in obtaining this office. He died in 1572. It was followed by Alessandro d'Este, who was born in April 1514, but died on July 10, 1516. Lucrezia's daughter Eleonora d'Este, who later became a nun, was born in 1515 and died in 1575. Francesco d'Este was born on November 1, 1516 and later became Prince of Massa. He married Maria di Cardona from the house of Folch de Cardona in 1540 and died on February 22, 1578. In autumn 1518, Lucrezia fell seriously ill during her last pregnancy. Shortly after the complicated birth of her daughter Isabella Maria, who died on the day of her birth on June 14, 1519, she had a letter dictated to Pope Leo X on June 22, 1519:

“Most Holy Father and my Adorable Lord. With all possible reverence of the soul I kiss the holy feet Ew. Bliss and humbly commend me in your holy grace. After suffering from a difficult pregnancy for more than two months, God gave birth to a daughter early in the morning on the fourteenth of this month, and hoped that after this birth, I would also be free from my sufferings; but the opposite has happened, so I have to pay tribute to nature. And so great is the favor that Our most gracious Creator gives me that I recognize the end of my life and feel how I will be taken from it in a few hours, after having previously received the holy sacraments of the Church. And at this point, as a Christian, though a sinner, I remember, Ew. To ask Holiness that you deign in your grace to give me a support from the spiritual treasure by giving my soul the holy benediction: And so I humbly ask you to do so and recommend Ew. Holy graces my lord consort and my children, which all Ew. Holiness are servants. In Ferrara on June 22nd, 1519 in the 14th hour Ew. Holiness humble servant Lucrezia of Este. "

She died in the presence of her husband and was deeply mourned by him on the night of June 24th in Belriguardo near Ferrara of puerperal fever . Alfonso d'Este wrote the following to his nephew Federigo Gonzaga after her death:

“Most noble sir, my adorable brother and nephew. Our Lord God it pleased, at this hour, to call the soul of the most illustrious Duchess, my dearest wife, what I Ew. Your Excellency cannot fail to communicate, for the sake of our mutual love, which makes me believe that the happiness and unhappiness of one are also those of the other. In order not to be able to write this without tears, it is so difficult for me to see myself being robbed of such a dear and sweet companion, for she was me through her good manners and the tender love that existed between us. With such a bitter loss, I would be in the consolation Ew. Your Excellency seek help, but I know that you too will take your part in the pain, and I will prefer to have someone who will accompany my tears with his rather than give me words of comfort. Ew. I commend glory. Ferrara on June 24th at the fifth hour of the night. Alfonsus, Duke of Ferrara. "

Lucrezia's grave is in the choir of the Corpus Domini monastery in Ferrara. A forelock from Lucrezia, which it had once given to the poet Bembo, was carefully kept by the latter and is today with his famous writings in the Bibliotheca Ambrosiana in Milan. On November 28, 2008, a painting by Dosso Dossi , known as the Portrait of a Youth and exhibited in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne , was identified by conservator Carl Villis as a possible portrait of Lucrezia Borgia. One of the arguments cited is that the dagger in the painting is supposed to symbolize the dagger that the Roman heroine Lucretia is said to have stabbed in her chest after being raped by Sextus Tarquinius . The myrtle bush and flowers are a reference to the Roman goddess Venus and feminine beauty. The dagger and the myrtle stand for Lucrezia's first name and surname, as the Borgias had chosen the goddess Venus as their emblem . The Latin inscription on the painting refers to the virtue and beautiful countenance of the person depicted.

Entrepreneurial activity

In northern Italy, Lucrezia acquired apparently worthless marshland, had it drained with the help of drainage ditches and canals and then used it as pasture or cultivation land for grain, beans, olives, flax and wine. Within six years she bought up to 20,000 hectares of land in northern Italy and made huge profits.

Legend

Lucrezia was married three times as the object of dynastic business and for the continued rise of the family. After Lucrezia's death, she was said to have had a number of affairs by her family's enemies, such as with Pietro Bembo and Gianfrancesco Gonzaga , the husband of her sister-in-law Isabella d'Este , all of which, however, belong in the realm of legend and cannot be substantiated by historical sources . The idea that she was a kind of early modern Messalina is one of the best-known stories about the Borgia family. The actual Borgia legend probably has its origins both in earlier demon narratives that circulated about the papacy in the first centuries, as well as in superstition and propaganda writings in the age of witch hunts and the Inquisition . Lucrezia came to the center of these reports because, according to Christian beliefs, such misconduct must have come from a woman. Shortly after Alexander's death, the papal master of ceremonies Johannes Burckard took over the design of the legend . Alexandre Dumas with his novel Les Borgia and Victor Hugo with his play Lucrèce Borgia shaped the image of Lucrezia as a woman with an extravagant lifestyle and an unscrupulous poisoner. The librettist Felice Romani made the libretto for the opera of the same name by Gaetano Donizetti from Hugo's original .

children

From her second marriage to Alfonso of Aragon:

- Rodrigo (born November 1, 1499, † August 1512)

From her third marriage to Alfonso I d'Este:

- Daughter, stillborn September 5, 1502

- Alessandro (born September 19, 1505, † October 14, 1505)

- Ercole II. D'Este (April 4, 1508, † October 3, 1559), Duke 1534 ⚭ June 28, 1528 Renée de France (1510–1574) daughter of King Louis XII.

- Ippolito II. D'Este (born August 25, 1509, † December 2, 1572), cardinal 1538

- Alessandro d'Este (April 1514 - July 10, 1516)

- Eleonora d'Este (July 4, 1515 - July 15, 1575), nun

- Francesco d'Este (born November 1, 1516, † February 22, 1578) Prince of Massa ⚭ 1540 Maria di Cardona († 1563) ( House Folch de Cardona )

- Isabella Maria (born and died June 14, 1519)

Artistic arrangements

Lucrezia's life served as a template for many artistic representations, books and films, in which she often takes on the role of a femme fatale .

- Victor Hugo wrote the theatrical tragedy Lucrèce Borgia about Lucrezia Borgia , to which Gaetano Donizetti composed an opera in 1833 based on a libretto by Felice Romani ( Lucrezia Borgia )

- Conrad Ferdinand Meyer wrote a novella Angela Borgia (1891). The fictional story revolves around Lucrezia and her distant relative Angela Borgia and various intrigues at the court of Ferrara

- Alfred Schirokauer : Lucretia Borgia. Historical novel. R. Bong, Berlin 1925

- Klabund : Borgia, novel of a family , 1928 (about Lucrezia Borgia, Cesare Borgia and their common father Pope Alexander VI. )

- Mario Puzo : Die Familie , published posthumously in 2001, historical novel, which, however, does not stick to the established historical facts, but rather processes the myriad of anecdotes in the form of a novel

Movies

Most of the films feature very free films that emphasize the erotic component of the material.

- 1910: Lucrezia Borgia, by Mario Caserini with Francesca Bertini

- 1910: Lucrezia Borgia, by Ugo Falena with Vittoria Lepanto

- 1912: Lucrezia Borgia, by Gerolamo Lo Savio

- 1919: Lucrezia Borgia, by Augusto Genina

- 1922: Lucrezia Borgia, by Richard Oswald

- 1935: Lucretia Borgia (Lucrecia Borgia) , by Abel Gance

- 1940: Lucrezia Borgia, by Hans Hinrich

- 1947: Lucrecia Borgia, by Luis Bayón Herrera

- 1953: Lucrezia Borgia (Lucrèce Borgia) , by Christian-Jaque based on the novel by Cécil Saint-Laurent

- 1958: The nights of love of Lucrezia Borgia (Le notti di Lucrezia Borgia) , by Sergio Grieco

- 1974: The Sins of Lucrezia Borgia (Lucrezia giovane) , by Luciano Ercoli

- 1974: Immoral Stories (Contes immoraux) , by Walerian Borowczyk

- 1982: Le notti segrete di Lucrezia Borgia, by Roberto Bianchi Montero

- 1990: Lucrezia Borgia, by Lorenzo Onorati

- 1994: Lucrezia Borgia, TV film by Tonino Delle Colle

- 2006: Los Borgia , by Antonio Hernández ; a portrait of the dynasty

- 2010: Borgia , TV series

- 2010: The Borgias , TV series directed by Neil Jordan

Computer games

See also

literature

- Sarah Bradford: Lucrezia Borgia. Penguin Group, London 2005, ISBN 0-14-101413-X .

- Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: the fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 (and Diederichs / Hugendubel, Kreuzlingen / Munich 2004, ISBN 3-424-01257-2 ).

- Ferdinand Gregorovius : Lucrezia Borgia according to documents and letters of her own time. Wolfgang Jess Verlag, Dresden 1952

- Massimo Grillandi : Lucrezia Borgia. Econ, Düsseldorf / Vienna / New York 1991, ISBN 3-430-13456-0 (also published as dtv paperback 2280 in 1991)

- Helmut Güttich: The other Lucrezia Borgia. A princely marriage in the Renaissance. Türmer, Berg 1987, ISBN 3-87829-102-7 .

- Friederike Hausmann : Lucrezia Borgia. Glamor and violence. Beck, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-406-73326-0 .

- Ernst Probst : Lucrezia Borgia - The beautiful daughter of a Pope. GRIN, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-640-90034-3 .

- Raffaele Tamalio: Lucrezia Borgia, duchessa di Ferrara. In: Mario Caravale (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 66: Lorenzetto – Macchetti. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2006, pp. 375-380.

- Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. Piper, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-492-24891-4 .

- Alois Uhl: Lucrezia Borgia: biography. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2008, ISBN 978-3-491-35021-2 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Lucrezia Borgia in the catalog of the German National Library

- FemBio.org: Lucrezia Borgia on the website of the Institute for Women's Biography Research

- Andrea Kath: June 24th, 1519 - Anniversary of the death of Princess Lucrezia Borgia WDR ZeitZeichen (podcast).

Individual evidence

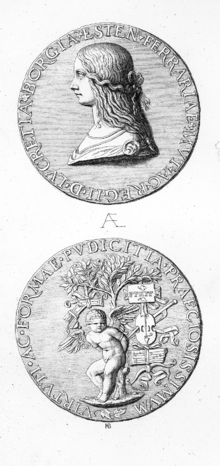

- ^ Probably coined on the occasion of Lucrezia's wedding to Alfonso d'Este. The medal was first described in 1806 by Julius Friedländer, director of the Berliner Münzcabinet . According to Ferdinand Gregorovius , it shows the only surviving, true-to-life picture of Lucrezia, but other depictions have since been discovered.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. Hamburg 2011, p. 23, limited preview in the Google book search

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 39 limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Sarah Bradford: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 17.

- ↑ Maike Vogt-Lüerssen: Lucrezia Borgia: the life of a papal daughter in the Renaissance. P. 94, ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Sarah Bradford: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 16.

- ^ Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 94.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 47, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 48, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Sarah Bradford: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 48.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 96 .

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 50, limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ a b Family tree of the Sforza family at genmarenostrum.com

- ↑ a b c Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 55, limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ a b c Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 56, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 49, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Sarah Bradford: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 24.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 54, limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ a b c Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 95.

- ^ Sarah Bradford: Lucrezia Borgia. P.56.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 78, limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ Christopher Hibbert: The Borgias and their enemies: 1431-1519. Harcourt, Orlando 2008, ISBN 978-0-15-101033-2 , p. 48.

- ↑ a b c Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 96.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 76, limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ staedelmuseum.de ideal portrait of a courtesan as Flora

- ↑ Maike Vogt-Lüerssen: Lucrezia Borgia: the life of a papal daughter in the Renaissance. P. 31, limited preview in Google Book search.

- ↑ Maike Vogt-Lüerssen: Lucrezia Borgia: the life of a papal daughter in the Renaissance. P. 32, limited preview in Google Book search.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 134 .

- ↑ Maike Vogt-Lüerssen: Lucrezia Borgia: the life of a papal daughter in the Renaissance. P. 33, limited preview in Google Book search.

- ↑ a b Alois Uhl: Pope's children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 97.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 135 .

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. Pp. 169–170, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Sarah Bradford: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 67.

- ↑ a b c Grandes de España-Gandía. (Spanish) at grandesp.org.uk

- ↑ Volker Reinhardt: The uncanny Pope: Alexander VI. Borgia 1431-1503. Munich 2007, p. 184, limited preview in the Google book search.

- ↑ a b Alois Uhl: Pope's children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 98.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 194 .

- ^ Fritz Meingast: Splendor and misery of women. Thirty-three portraits of world history. Wiesbaden 2003, pp. 121-122.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 194-195 .

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 195 .

- ^ Sarah Bradford: Cesare Borgia: his life and times. London 1976, pp. 161-162.

- ^ Sarah Bradford: Cesare Borgia: his life and times. P. 162.

- ^ Fritz Meingast: Splendor and misery of women. Thirty-three portraits of world history. P. 122.

- ^ Sarah Bradford: Cesare Borgia: his life and times. P. 88.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 208 .

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 58, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 99.

- ↑ Maike Vogt-Lüerssen: Lucrezia Borgia: the life of a papal daughter in the Renaissance. P. 54, limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 211 .

- ↑ a b Alois Uhl: Pope's children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 100.

- ↑ Maike Vogt-Lüerssen: Lucrezia Borgia: the life of a papal daughter in the Renaissance. P. 54, limited preview in Google Book search.

- ^ A b Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 176.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 210 .

- ^ Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. Pp. 99-100.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 210-211 .

- ↑ a b Ernst Probst: Lucrezia Borgia - The beautiful daughter of a Pope. P. 25 limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 79.

- ^ A b Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 220 .

- ^ A b Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 221 .

- ↑ Johannes Burcardus, Martin Müller: Church princes and intrigues: unusual court news from the diary of Johannes Burcardus, papal master of ceremonies with Alexander VI. Borgia. Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1990, ISBN 3-7608-0654-6 , pp. 176/177.

- ↑ a b Alois Uhl: Pope's children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 102.

- ^ Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 101.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 222 .

- ^ Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 104.

- ↑ Maike Vogt-Lüerssen: Lucrezia Borgia: the life of a papal daughter in the Renaissance. P. 71, limited preview in Google Book search.

- ↑ Joachim Brambach: The Borgia: Fascination of a power-obsessed Renaissance family . Callwey, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7667-0906-2 , p. 278-279 .

- ^ Fritz Meingast: Splendor and misery of women. Thirty-three portraits of world history. P. 127.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 286, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ A b Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 279, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ A b Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 277, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ A b Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 282, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. Pp. 273-274.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. Pp. 290-291.

- ^ Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 105.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 292.

- ^ Alois Uhl: Pope children. Life pictures from the time of the Renaissance. P. 188.

- ↑ Mystery portrait is Lucrezia Borgia, claims gallery , guardian.co.uk

- ↑ Lucrezia Borgia, Duchess of Ferrara by Dosso Dossi ( Memento of April 8, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), artmuseumjournal.com

- ↑ History, financial genius instead of femme fatale. Findings from historian Diane Yvonne Ghirardo of the University of Southern California In: Der Spiegel. No. 4, January 19, 2009.

- ↑ Ernst Probst: Lucrezia Borgia - The beautiful daughter of a Pope. P. 39 limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ Bernd Ingmar Gutberlet: The 50 greatest lies and legends in world history. P. 111.

- ↑ Bernd Ingmar Gutberlet: The 50 greatest lies and legends in world history. P. 114.

- ↑ Bernd Ingmar Gutberlet: The 50 greatest lies and legends in world history. P. 115.

- ^ Fritz Meingast: Splendor and misery of women. Thirty-three portraits of world history. P. 121.

- ↑ a b c d Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 305, limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ a b c Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 288, limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia. P. 300, limited preview in Google Book search

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Borgia, Lucrezia |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Borgia, Lucretia; Borja, Lucrecia |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian-Spanish Renaissance princess |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 18, 1480 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Rome or Subiaco |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 24, 1519 |

| Place of death | Belriguardo near Ferrara |