Ferdinand Gregorovius

Ferdinand Adolf Gregorovius (born January 19, 1821 in Neidenburg , Masuria , Kingdom of Prussia , † May 1, 1891 in Munich ) was a German writer, journalist and self-taught historian. After studying theology and obtaining a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Königsberg, he moved to Italy in 1852 at the age of 31, where he then lived as a private scholar in Rome . He only moved back to Germany in 1875. He spent his old age in Munich.

Gregorovius' monumental history of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages , on which he worked for over 18 years and for which he opened up numerous archival documents, is considered a classic of historiography. The years of travel he wrote in Italy , which arose from journalistic work, are still considered to be the most important contribution after Goethe's Italian trip to the German image of Italy . Most of the travelogues it contains belong to the genre of historical landscape descriptions that Gregorovius founded in his book Corsica (1854). He also wrote a history of the city of Athens in the Middle Ages (1889). His biography Lucrezia Borgia and her time , published in 1871, is still considered a standard work today. Gregorovius performed with works like Euphorion. A poem from Pompeii in four songs (1858) also appears as a poet. His posthumously published diaries not only provide insight into his life and work, but also contain comments on the political events of the Risorgimento . With several thousand letters Gregorovius left an extensive epistolary work.

Gregorovius, who often drew his motivation for his work from perception, saw himself as a writer with artistic aspirations. Along with Theodor Mommsen and Leopold von Ranke, he is still one of the most widely read historians of the 19th century. The literary value of his historiographical work is undisputed. Specialist historians accused Gregorovius for a long time of dilettantism , but the recognition of his work was reflected in his membership in numerous well-known academies during his lifetime. More recent research is trying to get a critical appreciation of his work.

Life

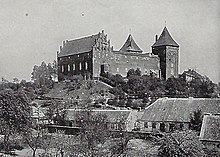

Gregorovius came from a Masurian family of pastors and lawyers. He was born on January 19, 1821, the son of Ferdinand Timotheus and Wilhelmine Charlotte Dorothea Kausch. His father was a district judicial officer in Neidenburg, East Prussia. He moved the responsible city council to expand the city castle ruins and make it the seat of the judiciary. In this way, the Gregorovius family lived with their eight children in the first years of Ferdinand's life in the medieval Neidenburg Castle . Ferdinand Gregorovius later claimed that without this experience he might never have written the history of Rome in the Middle Ages. Gregorovius' mother died in 1831, at a time when he was barely ten years old. In 1832, the young Ferdinand Gregorovius moved with his brother Julius to his uncle's house in Gumbinnen , where they attended the grammar school, the Friedrichschule , until he was seventeen . His older brother Gustav moved to Greece in 1833 to fight against the Ottomans as a philhellenic freedom fighter in King Otto's army .

University years in Königsberg

After graduating from high school, Ferdinand Gregorovius began studying Protestant theology at the Albertus University in Königsberg in autumn 1838 at the request of his father . Philosophy, history and literature soon emerged as his real interests. As the fourth of his family, Ferdinand Gregorovius became a member of the Corps Masovia . On September 10, 1840, he took over as Entrepreneur part in a torchlight procession with which the Konigsberg students Friedrich Wilhelm IV. , And his wife Elizabeth Ludovika of Bavaria when he took office homage .

After Gregorovius had passed his theologian exam in autumn 1841, he preached twice, in the Evangelical Parish Church of the Rhine and in his home town of Neidenburg. In Rhine his uncle, Superintendent Pianka, is said to have praised the sermon, but advised Gregorovius against further pulpit speeches. Gregorovius himself considered himself unsuitable for the profession of pastor and resumed studying philology. Karl Gutzkow and Young Germany worked in this turning away from theology . Gregorovius wrote his doctoral thesis on the aesthetics of Plotinus under Karl Rosenkranz , who introduced him to Hegel's philosophy . In 1843 he was promoted to Dr. phil. PhD. When he left the Albertus University, he received a Comitat from the Königsberg Seniors' Convent . Masovia elected him honorary corps boy.

Gregorovius' first literary activity fell at the same time. In 1843, under the pseudonym Ferdinand Fuchsmund, his anti-Jesuit satire Konrad Siebenhorn's Höllenbriefe to his dear friends in Germany was published . After two years as a private tutor in the provinces, he returned to Königsberg. He taught at a private school. In 1845 he published his first and only novel Werdomar und Wladislaw. From the desert of romanticism , which contains the story of two friends, one Prussian and one Polish, who are persecuted for their liberal ideas. From 1845 Gregorovius was involved in the "Königsberger Bürgergesellschaft". During the Revolutionary Biennium of 1848/49 he was a member of the "Provincial Committee for Popular Elections" and the "Democratic-Constitutional Club". In 1849 he was a member of the democratic provincial congress in Königsberg. He was editor of the Neue Königsberger Zeitung , for which he wrote 92 leading articles from May 1848 to the end of the newspaper in June 1850, and an employee of the Hartungschen Zeitung . In 1848 his two-volume book The Idea of Polity was published , in which he expressed his sympathy for the long oppressed Polish nation. In 1849 he published the Polish and Magyar songs as well as the study of Göthe's Wilhelm Meister in its socialist elements . The historian Wilhelm Karl August Drumann encouraged Gregorovius' interest in history and encouraged him to write his first historical work on the Roman Emperor Hadrian , which appeared in 1851. At the same time, the tragedy The Death of Tiberius was created , which transfers the disappointment with the political conditions of the present to the Roman emperor. With these two works, Gregorovius chose Italy as the setting for the first time. In the foreword to the second edition of “The Emperor Hadrian” published in 1884, he later claimed, one-sidedly and in a simplistic way, that this book was for him “the guide to Rome”. In 1852 he published his "Sommeridyllen vom Samländischen Ufer" in the magazine Deutsches Museum edited by Robert Prutz , which anticipated the genre of his later landscape and travel descriptions.

Life in rome

In April 1852 Gregorovius left the city of Kant to travel to Italy via Posen and Vienna after visiting his family in Neidenburg . This was preceded, as is known from a letter to his friend Ludwig Bornträger (1828-1852), a preoccupation with Italian Renaissance literature, especially reading Dante , Ariost , Tasso and Macchiavelli . In the same letter, Gregorovius revealed to the painter Bornträger his disappointment at the failure of the March Revolution and his internal crisis, which he justified with the state of German literature after Goethe. There was also a lack of academic prospects - after his political commitment during the revolution, a habilitation was no longer an option. Bornträger, who had set out for Italy with his mother Klara Josephe to alleviate a lung condition, offered him a travel credit of 300 thalers. Italy thus appeared to Gregorovius in 1852 as “'salvation' from personal hopelessness” and as “political and existential exile”. In Vienna, Gregorovius learned of Bornträger's death in Pisa , and the further journey via Trieste and Venice to Florence "was in deep depression". In Florence Gregorovius met Klara Bornträger, whom he accompanied back to Trento , in order to return from there to the Arno city. In Livorno , Gregorovius decided to go over to Corsica . Three months of hikes followed on the Mediterranean island, which stabilized him mentally. Looking back, Gregorovius wrote in his diary about the effects of his stay in Corsica:

“Corsica wrested my troubles, it purified and strengthened my mind; it freed me through the first work, the material of which I had won from great nature and life itself; it then put solid ground under my feet. "

Gregorovius processed his experiences in Corsica in a series of articles for the renowned Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung , an organ of the Cotta publishing house. In 1854 his travelogue appeared in an expanded form in a two-volume book version. The journalistic work for the organs of the publishing house Cotta not only brought Gregorovius reputation, it was also well paid and thus proved to be a means of livelihood in his early Italian years.

After a stay of several days on Elba , from which also a literary travelogue came over Gregorovius emerged, Livorno to Siena . On October 2, 1852, after traveling in a Vetturin car, he reached Rome. First he rented an attic from a sculptor in Via Felice 107. At the end of 1854 he moved to Via della Purificazione, known as the “Ghetto of German Artists”. From 1860 he lived in an apartment in Via Gregoriana 13. During his Roman years Gregorovius also enjoyed staying in the small town of Genzano in the Alban Hills southeast of Rome. In May 1853 he traveled there for the first time via Albano, then via the Pontine Marshes and the Garigliano areas he reached Capua and finally Naples . In Campania he visited Pompeii in July 1853 together with Friedrich Althaus and Jacob Burckhardt Nocera , Salerno and the temple ruins of Paestum . Burckhardt's project, decided later with the publication of the Cicerone , to write a treatise on the works of art in Italy, Gregorovius does not mention in his diary; a later meeting between the two historians is not known. Gregorovius hiked with Althaus on foot to Amalfi and Sorrento . Gregorovius stayed on Capri for a month . In the autumn he traveled to Sicily , where he visited Palermo , Segesta , the temples of Agrigento , Catania , Syracuse , Taormina and Messina and climbed the summit of Mount Etna . Gregorovius processed these trips in several articles for the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung, which appeared in a revised and expanded form later in his traveling years in Italy . He adhered to a plan to write a three-volume account of “Cultural Fragments from Sicily” until 1855, but then rejected it.

One of his first Roman friends was the Verona-born Dante connoisseur Count Paolo Perez, with whom he not only wandered through the Roman ruins, but also visited Rome's poetic circles. Perez joined the Rosminian Order in 1856 . Between January and April 1854, Gregorovius worked on the study “The Tombs of the Popes”, which appeared in the same year in the General Monthly for Science and Literature and three years later in book form. In 1856 he published a translation of the Sicilian songs Giovanni Melis . According to Gregorovius' diary, the decision to write a history of Rome in the Middle Ages was made on October 3, 1854, when I saw the city from the Tiber island of San Bartolomeo: “I have to do something great that would give my life content.” With the writing of the first Gregorovius began the tape on November 12, 1856. He worked for 18 years on the epochal work that became the “fulfillment of his life”. An "identity of person, work and historical environment" was characteristic of the following period. He turned down a scholarship offered to him by Grand Duke Carl Alexander of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach in 1858 , as well as funding from the Schiller Fund . At the instigation of Thiles and with the support of Christian Karl Josias von Bunsen , the Prussian government financed the writing of the history of the city of Rome with 400 thalers a year from 1860, which enabled Gregorovius to complete his work. In 1866 this funding was reduced to 200 thalers, which Gregorovius refused, whereupon he was paid the original amount again from 1868 to 1870. Gregorovius suffered from migraines, fever and chronic lack of sleep, which made him unable to work for long periods. He enjoyed and needed the “magical silence” of papal Rome. Rome had become his home. Here he made friends like Hermann von Thile , Clemens August Alertz , Eduard Mayer , Karl Lindemann-Frommel , Malwida von Meysenbug and Ersilia Caetani Lovatelli . He had a close friendship with Pauline Hillmann, the daughter of an East Prussian landowner, who stayed in Rome with Gregorovius' cousin Aurora in the winter of 1856/57 and died of a fever in Florence in 1866. A relationship of competition developed with Alfred von Reumont , who published the first volume of a three-volume history of Rome in 1857, whereby Gregorovius forbade any comparison with von Reumont - on June 14, 1868 he noted in his diary: “Reumont's work is one Compilation, which took him a year for the whole Middle Ages; my work is an original work, originating from research on sources for almost sixteen long years. ”In addition, as his diary shows, Gregorovius regarded Theodor Mommsen , who was working on Roman history at the same time as Gregorovius , as his antipode.

In contrast to the majority of his German contemporaries, Gregorovius took a sympathetic part in the events of 1859/60, the Second War of Independence and the Garibaldine procession of a thousand , which led to the founding of the Italian nation state in 1861. His philo-organizational attitude manifests itself above all in the diary entries. In 1859 Gregorovius traveled to the Montecassino monastery to study sources . In the summer of 1860 he returned to his homeland for the first time in eight years; the return journey took place via southern France. In August and September 1861 Gregorovius visited Perugia and Florence for a few days , where he met the politician and historian Michele Amari . In the summer of 1862 he traveled again to Germany via Switzerland , this time to Bavaria . From July to September 1863 Gregorovius undertook an extensive journey through Switzerland, southern Germany, Austria and northern Italy. In August and September 1864 Gregorovius drove with Karl Lindemann-Frommel and his wife to Naples, where he worked in the State Archives, and to Sorrento. In the summer of the following year he traveled to Kufstein and Munich via Florence . For the Berliner National-Zeitung he wrote a report on the Thiersee Passion Play , which he attended on July 29th. The return journey took place via Innsbruck , Bozen , Bologna and Florence. 1866 became a "year of mourning" for Gregorovius through the loss of Pauline Hillmann and his brother Rudolf. In the first days of January 1867, Gregorovius wrote the essay "The Empire, Rome and Germany" for the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung. In October he witnessed the Garibaldine attempt to conquer Rome, which ended on November 3rd in the defeat at Mentana by papal and French troops. Gregorovius reported on these events for the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung in a multi-part series of articles. In 1871 this article appeared in an expanded form under the title “The War of the Free Couples Around Rome” in the fourth volume of his “Wanderjahre”.

After completing the history of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages, Gregorovius decided to return to Germany. The conclusion of his Roman years was the writing of a monograph on Lucrezia Borgia and a trip to southern Italy with Raffaele Mariano . The latter served as the basis for the “Apulian Landscapes”, the last volume of the “Wanderjahre” published in 1877. In the last Roman diary entry of July 14, 1874 it says: “My mission in Rome has ended. I was an ambassador here in the most modest form, but perhaps in a higher sense than diplomatic ministers. "

Old age in Munich, trip to Greece and the Orient

In 1874 he moved to Munich, where he lived with a widowed sister and an unmarried brother at 5 Barerstrasse. Gregorovius chose Munich because of the library, some personal contacts and the relative geographical proximity to Italy. Every year he returned to Rome for several months at the onset of winter. In 1876 Gregorovius became the first German and the first Protestant honorary citizen of Rome. After completing his history of the city of Rome, Gregorovius fell into an internal crisis which he described as follows:

“I felt more and more that since the end of my great work there remained a gap in me which I absolutely cannot fill; because up to the present day no future-oriented thought has come before me. I am like a turtle that has come to lie on its back on the seashore. "

When asked by the publishing house CH Beck to write a history of the German people in one volume, he responded evasively. He also declined invitations from Grand Duke Carl Alexander to write a history of the Wartburg or a biography of Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar . In 1878 the Italian Queen Margherita asked him unsuccessfully in a private audience to write the history of the Savoy family . For several years Gregorovius worked on a representation of the Thirty Years War , but finally gave up the project in favor of the history of the city of Athens in the Middle Ages . Gregorovius again drew the motivation for the latter project from his own views: in 1880 he went on a two-month trip to Greece . This also inspired him in the manner of the "years of travel" to write Corfu, which appeared in 1882 . An Ionic idyll and a sketch from the Athens landscape. In the spring of 1882 he made an extensive journey to the Orient, during which he visited Egypt , Syria , Turkey and Jerusalem . Gregorovius also planned to write a history of Jerusalem, but it did not materialize. In 1882 he published the biography of Athenais . Story of a Byzantine empress about the wife of the Eastern Roman emperor Theodosius II.

After the fall of the secular papacy and the declaration of Rome as the capital of the Kingdom of Italy , Gregorovius viewed the architectural transformations in Rome with pain and regret. The intensive construction activity, such as the Tiber regulation , also fell victim to numerous medieval buildings. Gregorovius saw the plans for the later Monumento a Vittorio Emanuele II with horror. On May 29, 1881, in a public lecture at the Academy of San Luca, he denounced this urban development. His four letters to the president of the academy, in which he suggested, among other things, that documentation of the building structure threatened by destruction, were unsuccessful. In 1886 he went over to public protest by having his letter of March 26th of this year to the President of the Academy published in the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung under the title “Der Umbau Roms”. This initiative also had no effect.

In 1889, after completing the history of the city of Athens, Gregorovius considered his work to be complete. On June 28, 1889, he drew up his will. In the fall of that year, after reviewing his papers, he turned over a large part of his personal documents and manuscripts to the fire. As the traces of fire show, some of the manuscripts were saved by him or his siblings at the last minute. He asked friends and acquaintances to destroy his letters. This fate also overtook the correspondence with Friedrich Althaus that had lasted over forty years .

Gregorovius died on May 1, 1891, at the age of seventy, of meningitis . After his death, his relatives telegraphed to Rome as he wished: “È morto Ferdinando Gregorovius, cittadino romano. Munich, May 1, 1891. “After his death, his family received more than 60 letters and telegrams of condolence, including famous senders from science, art and European aristocracy and royalty. Gregorovius' body was cremated , his ashes were probably buried in an urn in the castle chapel of Georg von Werthern in Beichlingen , from where they later came to Neidenburg. There the urn was destroyed during the Second World War.

Self-image

During the early Italian years Gregorovius wavered between poetry, literary journalism, and historiography. This parallelism of interests was basically retained later, but since the decision made in 1854 to write the history of the city of Rome, historiography has been given increasing priority.

In a letter to Georg von Cotta , Gregorovius characterized his self-image as a historian as follows:

“I am not a pupil of Mr. Ranke (to be one would certainly bring me honor); my individuality is entirely different from the manner of the famous man, and I alone pursue my path. I am trying to combine research and artistic representation and I would also like to be admitted that I have the art of storytelling, which is not common in Germany. "

Until well into the 1860s, Gregorovius saw himself - increasingly counterfactually - as a man of letters who, among other things, carried out historical studies. Gregorovius understood his historiography “as poetry with artistic claim”.

Characteristic of Gregorovius' life and work are "outsiders", "lonerism" and the "l'art pour l'art standpoint". Gregorovius wanted to keep his "freedom and independence" as a private scholar. Therefore, he deliberately renounced a professorship in Germany and turned down the invitations of Grand Duke Carl Alexander and Maximilian II to Weimar and Munich.

Gregorovius often drew the motivation for his work from his own point of view, in line with Goethe's concept. This differs fundamentally from other historians of Rome such as Theodor Mommsen or Barthold Georg Niebuhr , who saw Rome for the first time after his Roman history was published.

plant

Corsica

Gregorovius' book on Corsica, published in 1854, is divided into two parts: a history of the island and a description of his wanderings. In the judgment of Francis Pomponi , the historical and literary order of the travelogue is “dissected by digressions and overloaded with excerpts from the writings of earlier authors”. Gregorovius did research well for his portrayal: He read the important works of the 18th century such as James Boswell's Account of Corsica , Giulio Matteo Natalis Disinganno intorno alla guerra di Corsica and Gregorio Salvinis Giustificazione della rivoluzione di Corsica ; he also took into account the more recent representations by Francesco Ottaviano Renucci and Joseph-Marie Jacobi; he also made contacts with local intellectuals. His travelogue is peppered with historical remarks, and in many cases his impressions evoke memories of antiquity . In addition, the narrative includes genre scenes, vivid portraits of people, and depictions of various social types. With the “view of the anthropologist” he describes and explains the customs and traditions of the Corsicans. In his presentation of the blood revenge (vendetta) Gregorovius refers to parallel customs in Calabria, Sicily, Albania and Montenegro and thus avoids the mistake of many other authors to present the vendetta as a peculiar Corsican phenomenon. In his ethnological interest in the history of the individual ethnic groups, influences of romanticism manifest themselves . When he speaks of the unspoiled “savages” and of a “democratic equality of life” in Corsica, the Enlightenment legacy of Rousseau is unrecognizable . At the same time, in contradiction to this, positivism and belief in progress announce themselves when Gregorovius recommends colonizing the archaic island for the benefit of its inhabitants and strengthening the infrastructure. Gregorovius blames the French government for the fatal conditions, and among other things, he strongly criticizes its customs regulations. According to Gregorovius, the Corsican is “decidedly Italian”.

Years of traveling in Italy

Gregorovius published the articles, which later became known under the name "Wanderjahre in Italien" (Wanderjahre in Italien), initially as articles in sheets of Cotta and Brockhaus Verlag: Many of his essays appeared anonymously in the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung, but with names in the Deutsches Museum , Sheets for literary entertainment , The Present and Our Time . In 1856 the band figures appeared in Brockhaus-Verlag . History, life and scenery in Italy , for which Gregorovius originally planned the title "Pandora". The publication of Siciliana followed in 1861 . Wanderings in Naples and Sicily , 1864 Latin summer . In 1870 a new edition of the volumes was published under the title Wanderjahre in Italien : The "Figures" formed the first volume of the collection, "Latin Summer" the second and the "Siciliana" the third. Volume 4 of the “Wanderjahre” was published in 1871 under the title From Ravenna to Mentana , and in 1877 the fifth and final volume Apulian landscapes .

Volume 1 contains the essays "The Elba Island", "The Ghetto and the Jews in Rome", "Idylls from the Latin Shore", "The Cap of the Circe", "Roman Figures", "San Marco in Florence", "Tuscan Melodies "And" The Island of Capri ". Volume 2 includes “Subiaco, the oldest Benedictine monastery in the West”, “From the Campagna of Rome”, “From the mountains of the Hernics”, “From the mountains of the Volscians”, “From the banks of the Liris”, “The Roman poets of the Present ”and“ Avignon ”. Volume 3 contains “Naples”, “Palermo”, “Agrigento”, “Syracuse”, “The Sicilian Folk Songs” and “Naples and Sicily from 1830 to 1852”. Volume 4 contains "Foray through the Sabina and Umbria", "The Empire, Rome and Germany", "The Orsini Castle in Bracciano", "The war of the free couples around Rome" and "A week of Pentecost in Abbruzzo". Volume 5 includes the essays "Benevento", "Lucera, di Saracenene-Colonie der Hohenstaufen in Apulia", "Manfredonia", "The Archangel on Mount Garganus," "Andria", "Castel del Monte, Castle of Hohenstaufen in Apulia" , “Lecce” and “Taranto”.

In contrast to the Cicerone , which was created almost at the same time . To learn how to enjoy the art of Italy Jacob Burckhardt chose Gregorovius in his "years of wandering" no systematic access, but preferred the representation of individual sites and landscapes, "which he confers a representative position by the exposure of their historical dimensions." The basis of all essays of " Wanderjahre "was the personal experience, especially" the hike through a landscape, meeting people, participating in traditional festivals. "The" Roman figures "are to be understood as a literary competition with Goethe's" Roman Carnival "and would be unthinkable without this model.

History of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages

Gregorovius' life's work, on which he worked for over 18 years, deals in eight volumes with the history of the city of Rome from the beginning of the fifth century to the end of the pontificate of Clement VII in 1534. One can put simply that the sack of Rome by the Visigoths under Alaric 410 and the Sacco di Roma by the troops of Emperor Charles V in 1527 form the cornerstones of his representation. His first manuscript was still entitled “Chronicle of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages”. Gregorovius understood Rome's “world reference” very broadly, so that his history of the city of Rome often includes the context of great European history and therefore does not deal with Rome itself on many sides. The original work has a rich annotation apparatus, which was only shortened or omitted in later editions. Gregorovius updated the work in several new editions.

The author began his presentation with a description of the 14 medieval districts of Rome (rioni) . This was followed by a general “View of the City of Rome in the Late Imperial Era”. Gregorovius then shows the changes that Christianity brought to Rome. He debunked the claim by Italian historians that the Goths destroyed Rome's structures in 410 as an exaggeration by showing that the city's monuments were indeed intact during this looting. Gregorovius also made a significant contribution to the research of the Roman city constitution, the fall of which he determined as early as the early Middle Ages .

According to Arnold Esch , Gregorovius' time-bound perspective is unmistakable: the nation-state principle characteristic of the 19th century was transferred to the late Middle Ages . Gregorovius deliberately avoided technical terminology. In Esch's judgment, Gregorovius ignored the economic history of Rome, but through his intention to write a comprehensive account, he had dealt with significantly more aspects than was customary at his time. So his performance was in a broad sense of cultural history also covers much of what was first produced in the 20th century as an independent methodological direction of historical research: everyday life , Micro history , durée Longue , demographics and "topography RELIGIEUSE".

For his work Gregorovius visited the Biblioteca Angelica , the Sessoriana and the Barberina in Rome . From 1859 he received access to the Biblioteca Vaticana through the intercession of Alfred von Reumont with Cardinal Giacomo Antonelli . He established contacts with numerous Italian archivists and historians, such as Michele Amari , Luigi Tosti and Tommaso Gar. Gregorovius used the Italian chronicles edited by Lodovico Antonio Muratori as an important source . He also used the great old document collections. From 1858 Gregorovius made repeated archive trips to other Italian cities. The Roman private archives became accessible to him early on. After the fall of the secular rule of the papacy in 1870/71, Gregorovius also had access to the archives of the Roman parish churches. The Vatican Archives remained closed to him.

In 1872 the Roman city council decided to print an Italian translation at the commune's expense. In 1874 the Vatican put the book on the Index librorum prohibitorum .

Seals

Gregorovius also appeared as a poet, especially in his early years. 1858 appeared Gregorovius' most successful poem in hexameters written epic Euphorion. A poem from Pompeii in four songs . In a private letter from 1864 Gregorovius complained about the extinction of his poetic power, for which he blamed the project of the history of Rome:

“The muse was dead in me, as it were, crushed by the great stone 'Rome'; and the poetic germs in me resembled or even resembled those tortured plant germs that you sometimes find in the field when you pick up a stone. "

According to Hanno-Walter Kruft , Gregorovius' lyrical work is " epigonal through and through ". In contrast to Mommsen, Burckhardt and many other scholars of the 19th century, however, his poems were not just adolescent experiments for him, but “a vital fiction that accompanied him into old age.” Ernst Osterkamp characterizes Gregorovius' poetic work as “almost consistently of oppressive mediocrity ”. Gregorovius himself was not unconscious of the low artistic value of his poems - with the exception of "Euphorion" and a few other small poems - because he burned some poems himself in 1860 and could never make up his mind to publish a volume of poetry. Only after his death did Adolf Friedrich von Schack publish his poems in a book in 1892.

Diaries

It is not known whether Gregorovius kept a diary before his trip to Italy in 1852. During the Italian years from 1852 to 1874 he regularly wrote a diary. These notes were "by no means written with a view to publication" but were "a personal statement of accounts". They give an insight into "the genesis of his work, the constantly expanding social ties and his participation in the Italian Risorgimento". In part, the records served as a material basis for Gregorovius' journalistic work and his later essays in the "years of traveling".

In the last years of his life, Gregorovius subjected his diary entries from the Italian years to a thorough revision before he left them to the London professor of German studies Friedrich Althaus , a long-time friend. Gregorovius had neither forbidden nor ordered publication, but Althaus interpreted Gregorovius' approach in such a way that publication was "in his wishes": Gregorovius not only revised the diaries before his death, they were also indicative of the extermination campaign of 1889 (see above) escaped. Althaus therefore published the records under the title "Roman Diaries" as early as 1892, the year after Gregorovius' death. Jens Petersen calls the diaries a “last document of self-styling”. According to Markus Völkel it is obvious that Gregorovius “only considered the span of his actual Roman existence worth communicating”, “his acme, which coincided with the creation of the 'History of the City of Rome'”. Gregorovius wanted his diaries to be read as “his last work of history”. In 1893 a slightly revised edition appeared. An Italian version was published in 1894 and reissued in the 1960s and 1970s, and an English translation was published in 1907. The original manuscript of the “Roman Diaries” is lost today.

On the 100th anniversary of Gregorovius' death, a complete edition of the “Roman” and “Post-Roman Diaries”, edited by Markus Völkel and Hanno-Walter Kruft, was published for the first time in 1991 . The latter are in Gregorovius' estate (the Gregoroviusiana), which is now in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich. Gregorovius kept the post-Roman diary until the end of October 1889, when it suddenly ended a year and a half before his death. The entries are less regular than in the Roman diaries. They turn out to be particularly detailed when they deal with the trips to Italy that Gregorovius undertook at regular intervals during his years in Munich.

Gregorovius used separate notebooks for the trip to Greece and the Orient, which have not been preserved.

Letters

Despite his attempt in 1889 to destroy part of his estate, several thousand letters from Gregorovius' pen have survived. According to Angela Steinsiek, his epistolar work is one of "the most important German corpora of the 19th century" and represents a "unique document of the European history of science in the 19th century". 2,000 known letters from Gregorovius are compared to the comparatively low number of 400 counter-letters. Gregorovius corresponded with German and Italian historians, writers, publishers, politicians and visual artists. The scope of his epistolar work shows his transnational networking in the European cultural world. Well-known correspondents included Berthold Auerbach , Michelangelo Caetani and Ersilia Caetani-Lovatelli, Robert Davidsohn , Ferdinand Freiligrath , Karl Gutzkow, Giovanni Gozzadini , Theodor and Paul Heyse , Alexander and Mathilde von Humboldt, Karl and Manfred Lindemann-Frommel , Raffaele Mariano, Malwida von Meysenbug , Hermann Reuchlin , Alfred von Reumont, Karl Rosenkranz, Adolf Friedrich von Schack, Salvatore Viale , Rudolf Virchow and Friedrich Theodor Vischer . One of the most extensive correspondence, with 118 letters, was that to Hermann von Thile.

drawings

In addition to his extensive literary work, Gregorovius left eight small-format sketchbooks containing around 400 drawings as well as travel notes, bibliographical information and accounts. They are part of the Gregoroviusiana. The drawings are mainly landscape representations. Gregorovius mainly used the pencil as drawing material, occasionally also the pen, whereas only one watercolor of him has survived. In his Italian years Gregorovius filled a total of six sketchbooks, ranging from 1852 to 1860: Gregorovius was particularly active in drawing from 1852 to 1855, while in 1858 there was a break; the last of the Italian sketchbooks is dated 1859/60. The next surviving sketchbook was not made until 20 years later. Coincidences of preservation can be responsible for this, but the art historian Hanno-Walter Kruft considers it more likely that Gregorovius only felt the need to draw at certain stages of his life.

Kruft sees diaries and sketchbooks as a "unit" that served as the "common basis for later elaboration in the 'years of traveling'". Gregorovius recorded “sensual-optical impressions” in order to later shape them linguistically. The drawings were never an end in themselves, but aimed at a "literary evaluation". Accordingly, according to Kruft, it would also be wrong to place Gregorovius as the holder of an artistic-literary dual talent on the same level as Salomon Gessner , Goethe, ETA Hoffmann , Gottfried Keller or Adalbert Stifter , for whom drawing and painting only represented other media of artistic expression.

Honors during your lifetime

- Member of the Royal German Society of Königsberg (December 6, 1860)

- Knight Order of St. Mauritius and Lazarus , Cavaliers (Turin, June 7, 1862)

- Corresponding member of the Kgl. Bavarian Academy of Sciences (July 25, 1865)

- Foreign member of the historical class of the Kgl. Bavarian Academy of Sciences (July 25, 1871)

- Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art (Hohenschwangau, November 22, 1871)

- Order of the Württemberg Crown , Knight (March 3, 1873)

- Corresponding member of the Deputazioni di storia patria per le Provincie di Romagna (Rome, April 24, 1873)

- Knight Order of St. Mauritius and Lazarus , Uffiziale (June 5, 1875)

- Admission to the Bavarian Academy of Sciences (1875)

- Admission to the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei (1876)

- Order of the Crown of Italy , Commendatore (June 30, 1876)

- Honorary Citizen of Rome (1876)

- House Order of the White Falcon , Komtur (September 9, 1879)

reception

Gregorovius in the judgment of contemporaries and posterity

Gregorovius was one of the most widely read German-speaking historians well into the 20th century. The literary quality of his historiographical work has never been disputed; However, some historians questioned their scientific value. Gregorovius was often denied recognition from the academic world, which accused him of dilettantism .

Jacob Burckhardt judged Ludwig von Pastor : "Gregorovius has his merits, but he leaves too much room for the imagination." Leopold von Ranke called Gregorovius a "historian for tourists", his history of the city of Rome was "Italianizing". For Karl Krumbacher "Gregorovius did not meet the highest standards as a historian". In his obituary he measured it against Ranke and Theodor Mommsen :

“He does not have the dramatic liveliness, the aphoristic brevity and the objective restraint through which Ranke has won the admiration of historians and has forfeited the effect on wider circles; he is far from the epigrammatic sharpness and the pithy, thought-heavy firmness which we admire in Mommsen; What defines his essence and strength is rather that epic flow of narration, animated by comfortably executed comparisons and effective images, rich in color, not afraid of repetition, but always elevated by moral warmth and elegant tone, which has been that since the days of Homer The most captivating of the people in the communication of historical events. "

Eduard Fueter judged Gregorovius' historiography in a similarly negative way in his 1911 History of Modern Historiography :

“Ferdinand Gregorovius' historiographical activity [...] was closely related to the aesthetic direction of Renan and Burckhardt. Except that Gregorovius was more heavy-blooded and mentally less agile than the two named. He was also less original. [...] He was a typical representative of the old-school traveler to Italy, who raved about ancient art, ruins and picturesque folk life and preferred to fill the imagination with atmospheric images than to soberly examine the real historical events. [...] He was a good portrayal and narrator, but not a great historian. "

In 1937, the renowned ancient historian Arnaldo Momigliano disparagingly referred to a "story à la Gregorovius" to mark a work that was unfounded in comparison to Edward Gibbon's History of the fall and decline of the Roman Empire .

However, from the beginning and also from the historians 'guild Gregorovius' biography Lucrezia Borgia and her time , published in 1871, received an undivided positive judgment . Wilhelm Dilthey praised the book with the words:

“Gregorovius created a well-founded story of this woman on the basis of documents, whose life was previously a novel. And here too, as in so many other cases, the events do not lose their magic in that they are traced back to their critical truth. This biography, presented in the brilliant language of the outstanding historian, is a valuable addition to our historical literature, which is intended for reading the educated. "

Current research still uses this work by Gregorovius as a standard work.

Bertrand Russell called the history of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages a “delightful book”. On February 19, 1948, on the occasion of his preparatory work for the novel The Chosen One, Thomas Mann noted : “In Gregorovius, who is interesting far beyond my subject.” Golo Mann called the history of the city of Rome “one of not too many perfect historical works in German ".

In more recent times, Gregorovius' merits have also been recognized from the academic side: According to Arnold Esch, Gregorovius proves himself to be an independent historian who expands the sources and critically evaluates in his portrayal of the late Middle Ages in the history of the city of Rome, better than most of his contemporaries and some of his successors ”. Hanno-Walter Kruft described Gregorovius' work as a "unique, very respectable achievement". Gregorovius wrote primarily literature and less historical research.

Posthumous honors

In Neidenburg, a monument with a memorial stone and semicircular benches commemorates the city's great son. In the Königsberg district of Maraunenhof a street bears his name. In Rome a street and a square are named after him. A road in Perugia and a smaller peak at Monte Rotonda in the Restonica Valley Aiguilles in Corsica are also named after Gregorovius. Forty years after his death, Benito Mussolini had a bust of Gregorovius installed in the Museo di Roma . In the hundredth year of his death, the city of Rome put a memorial plaque on Via Gregoriana 13, on Gregorovius' long-term home, and the community of Genzano donated a plaque. The Associazione Culturale Romana In 1991, a plaque on the house (in the Via di Pietra) that after his arrival in Rome lived in the Gregorovius in October 1852 initially.

Fonts

- Konrad Siebenhorn's Höllenbriefe to his dear friends in Germany , edited by Ferdinand Fuchsmund (pseud. For F. Gregorovius). Königsberg, Th. Theile, 1843. New edition (edited by Ferdinand Fuchsmund and Hans-Joachim Polleichtner) ,hochufer.com, Hanover 2011, ISBN 978-3-941513-18-1 .

- Werdomar and Wladislav from the desert romance. (Novel). 2 parts in 1 volume. Königsberg, university bookstore, 1845.

- The idea of polity. Two books on the Polish history of suffering (1848)

- Polish and Magyar songs (1849)

- Göthe's Wilhelm Meister developed in its socialist elements (1849)

- The death of Tiberius (tragedy, 1851)

- Corsica . 1854. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1988, ISBN 3-7973-0274-6 .

- History of the Corsican . 1854.hochufer.com, Hannover 2009, ISBN 978-3-941513-05-1 .

- Corsica. From my wanderings in the summer of 1852 . 1854.hochufer.com, Hannover 2009, ISBN 978-3-941513-06-8 .

- The history of the Corsican and Corsica. From my wanderings in the summer of 1852 together form a complete new edition of Gregorovius' Corsica work.

- Europe and the revolution. Editorial 1848–1850. Edited by Dominik Fugger and Karsten Lorek, CH Beck, Munich 2017.

- History of the Roman Emperor Hadrian and his time. 1851. (online) , new publication as Hadrian und seine Zeit. Glory and fall of Rome. Edition in a bottle in the Wunderkammer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-941245-08-2 .

- Idylls from the Baltic shore. 1856, new edition 1940. Graefe and Unzer. Koenigsberg. hochufer.com, Hannover 2011, ISBN 978-3-941513-17-4 .

- The tombs of the Roman popes. Historical Studies (1857)

- History of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages . 1859-1872. New edition, 2nd edition. 4 volumes. Beck, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-406-07107-4 .

-

Years of traveling in Italy . 1856-1877. 5th edition. Beck, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-406-42803-7 .

- The ghetto and the Jews in Rome . Schocken, Berlin 1935 ( Schocken Verlag Library No. 46)

- History of the city of Athens in the Middle Ages. From the time of Justinian to the Turkish conquest . 1889. dtv, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-423-06114-6 .

- Lucretia Borgia and her time , 1874, new edition, Wunderkammer, Neu-Isenburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-941245-04-4 (= edition in a bottle ).

- Naples and Capri . Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1944 ( Insel-Bücherei 340/2)

- The island of Capri - idyll of the Mediterranean . Wolfgang Jess Verlag, Dresden 1952.

- Capri. Corfu. Idylls from the Mediterranean. hochufer.com, Hannover 2013, ISBN 978-3-941513-28-0 .

- Euphorion. A poem from Pompei in four songs . FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1858 books.google

- Athenais. Story of a Byzantine Empress (1882)

- A trip to Palestine in 1882. (First published in 1883 and 1884) CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-38546-X .

- The Emperor Hadrian. Paintings from the Roman-Hellenic period in his time (1884)

- Small writings on history and culture , 3 volumes (1887-1892)

- Poems (1892)

- Roman diaries 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 .

- Letters to Konigsberg. Edited by Dominik Fugger and Nina Schlüter, CH Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-65012-3 .

- Poetry and science. Collected German and Italian letters. ( Digital Edition ), edited by Martin Baumeister and Angela Steinsiek, German Historical Institute in Rome 2020.

literature

- Alberto Forni: La questione di Roma medievale. Una polemica tra Gregorovius e Reumont. Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, Rome 1985.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Gregorovius, Ferdinand. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 2, Bautz, Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-032-8 , Sp. 343-344.

- David S. Chambers: Ferdinand Gregorovius and Renaissance Rome. In: Renaissance Studies. Journal of the Society for Renaissance Studies. Vol. 14 (2000), H. 4, pp. 409-434.

- Arnold Esch and Jens Petersen (eds.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome. Vol. 78). ( Review , conference report )

- Dominik Fugger : A life as a private scholar. Ferdinand Gregorovius in his letters to Königsberg. In the S. and Nina Schlüter (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius: Briefe nach Königsberg 1852-1891. CH Beck, Munich 2013, pp. 7–31 ( PDF online ).

- Johannes Hönig : Ferdinand Gregorovius, the historian of the city of Rome. With letters to Cotta, Franz Rühl, among others, Cotta, Stuttgart 1921.

- Johannes Hönig: Ferdinand Gregorovius: a biography. 2nd completely new edition, Stuttgart 1944.

- Heinrich Hubert Houben : Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233-271 ( digitized version ).

- Waldemar Kampf : Gregorovius, Ferdinand Adolf. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1966, ISBN 3-428-00188-5 , pp. 25-27 ( digitized version ).

- Waldemar Kampf: Ferdinand Gregorovius and the politics of his time. In: Preußenland , Volume 19 (1981), pp. 18-24.

- Waldemar Kampf: Origin, recording and impact of the “History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages”. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: History of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages. From V. to XVI. Century. Vol. 4, edited by Waldemar Kampf, Munich / Darmstadt 1976, pp. 7–54.

- Hanno-Walter Kruft : The historian as a poet. On the 100th anniversary of Ferdinand Gregorovius' death. Publishing house of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7696-1564-6 ( PDF online ).

- Norbert Miller : Poetically developed story. Ferdinand Gregorovius' “Years of Wandering in Italy” and his poetry about the garden of Ninfa. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries , Vol. 96 (2016), pp. 389–411 ( online ).

- Henry Simonsfeld : Gregorovius, Ferdinand . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 49, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1904, pp. 524-532.

- Angela Steinsiek: The epistolic work of Ferdinand Gregorovius. An inventory. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries , Vol. 97 (2017), pp. 290-315 ( online ).

Web links

- Edition project Ferdinand Gregorovius: Poetry and Science. Collected German and Italian letters

- Literature by and about Ferdinand Gregorovius in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Ferdinand Gregorovius in the German Digital Library

- Works by Ferdinand Gregorovius in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Hansjakob Stehle : Freedom and the sun are all I desire . In: The time . April 26, 1991.

- Hansjakob Stehle: literary travel companion: Gregorovius' Italy. In: Die Zeit , March 29, 1985.

- Ferdinand Gregorovius and the Villa Malta in Rome

- Ferdinand Gregorovius: Idylls from the Latin bank. Historical landscapes from the area around Rome: Antium (Anzio), Nettuno, Torre Astura

- Capri motifs on postcards with description of the island by Ferdinand Gregorovius u. a.

- Gregorovius, Ferdinand . In: East German biography (Kulturportal West-Ost) (Würzburg 1955)

- The estate is in the Bavarian State Library

- All drawings from the estate have already been digitized (seven sketchbooks)

- Short biography

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jens Petersen : The image of contemporary Italy in the years of travel by Ferdinand Gregorovius. In: Arnold Esch , Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 73–96, here p. 74.

- ^ Alberto Forni: Gregorovius, Ferdinand. In: Mario Caravale (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 59: Graziano – Grossi Gondi. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2002.

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben : Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233–271 ( digitized version ), here p. 235.

- ^ Markus Völkel , Hanno Walter-Kruft : Introduction. In: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 10.

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben: Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233–271 ( digitized version ), here pp. 235 f .; Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 10.

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben : Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233–271 ( digitized version ), here p. 236; Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 10.

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben: Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233–271 ( digitized version ), here p. 236; Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 10.

- ↑ Kösener Corpslisten 1930, 89/292

- ^ Johannes Hönig : Ferdinand Gregorovius . Cotta, Stuttgart 1943, pp. 34-35.

- ^ Johannes Hönig: Ferdinand Gregorovius . Cotta, Stuttgart 1943, p. 36.

- ↑ Dissertation: Plotini de pulcro doctrina . For a publication in German cf. Ferdinand Gregorovius: Basic lines of an aesthetic of Plotinus. In: Journal for Philosophy and Philosophical Criticism. New Series, Vol. 26 (1855), pp. 113-147.

- ↑ Jens Petersen: The image of contemporary Italy in the years of travel by Ferdinand Gregorovius. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 73–96, here p. 74; Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 11.

- ↑ Dominik Fugger: Giving the events a meaning. Ferdinand Gregorovius and his leading articles for the Neue Königsberger Zeitung. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Europe and the revolution. Editorial 1848–1850. Edited by Dominik Fugger and Karsten Lorek, CH Beck, Munich 2017, pp. 13–29, here p. 13.

- ^ Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 11.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 1–11, here p. 2.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 1–11, here p. 2.

- ↑ Dominik Fugger: A life as a private scholar. Ferdinand Gregorovius in his letters to Königsberg. In the S. and Nina Schlüter (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius: Briefe nach Königsberg 1852-1891. CHBeck, Munich 2013, pp. 7–31 ( PDF online ), here p. 16.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 1–11, here p. 2.

- ↑ Jens Petersen: The image of contemporary Italy in the years of travel by Ferdinand Gregorovius. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 73–96, here p. 75.

- ^ Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 12.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , p. 44 (entry for the year 1852).

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , p. 44 (entry for the year 1852).

- ↑ Jens Petersen: The image of contemporary Italy in the years of travel by Ferdinand Gregorovius. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 73–96, here p. 75.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , p. 44 (entry for the year 1852).

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben: Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233–271 ( digitized version ), here p. 249.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. With twenty-seven contemporary illustrations. 5th edition, CH Beck, Munich 1997, pp. IX-XVII, here p. XV.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , p. 47 (entry June 24, 1853).

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , p. 49 (Itinerarium).

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben: Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233–271 ( digitized version ), here pp. 252–255.

- ^ Alberto Forni: The success of Gregorovius in Italy. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 12–41, here pp. 13–16; Angela Steinsiek: The epistolic work of Ferdinand Gregorovius. An inventory. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries , Vol. 97 (2017), pp. 290-315 ( PDF online ), here p. 309.

- ↑ Michael Borgolte: Between “English essay” and “historical study”, Gregorovius' “Tombs of the Popes” from 1854/81. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 96–116.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), p. 1–11, here p. 3 f.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: The historian as a poet. On the 100th anniversary of Ferdinand Gregorovius' death. In: Meeting reports of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class , Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7696-1564-6 , pp. 1–18 ( PDF online ), here p. 9.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: The historian as a poet. On the 100th anniversary of Ferdinand Gregorovius' death. In: Meeting reports of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class , Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7696-1564-6 , pp. 1–18 ( PDF online ), here p. 16.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: The historian as a poet. On the 100th anniversary of Ferdinand Gregorovius' death. In: Meeting reports of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class , Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7696-1564-6 , pp. 1–18 ( PDF online ), here p. 12.

- ↑ Dominik Fugger: A life as a private scholar. Ferdinand Gregorovius in his letters to Königsberg. In the S. and Nina Schlüter (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius: Briefe nach Königsberg 1852-1891. CHBeck, Munich 2013, pp. 7–31 ( PDF online ), here p. 23.

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben: Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233–271 ( digitized version ), here p. 265.

- ↑ Markus Völkel: Seeing Rome - the first complete edition of the “Roman Diaries 1852–18889” by Ferdinand Gregorovius. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 59–72, here p. 67.

- ^ So Gregorovius in the diary entry of January 12, 1873. Quoted by Hanno-Walter Kruft: The historian as a poet. On the 100th anniversary of Ferdinand Gregorovius' death. In: Meeting reports of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class , Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7696-1564-6 , pp. 1–18 ( PDF online ), here p. 12.

- ↑ Dominik Fugger: A life as a private scholar. Ferdinand Gregorovius in his letters to Königsberg. In the S. and Nina Schlüter (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius: Briefe nach Königsberg 1852-1891. CHBeck, Munich 2013, pp. 7–31 ( PDF online ), here p. 25.

- ^ Arnold Esch: Gregorovius as a historian of the city of Rome: his late Middle Ages in today's perspective. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 131–184, here p. 159.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 1–11, here p. 5.

- ^ Wolfgang Altgeld : Gregorovius and the emergence of the Italian nation state. In: Annali dell ' Istituto storico italo-germanico , Vol. 18 (1992), pp. 223-238; Jens Petersen: The image of contemporary Italy in Ferdinand Gregorovius' years of traveling. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 73–96.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 85-90.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 103-112.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , p. 136 f.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 148-155.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 162-172.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 182-186.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 196-200.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , p. 220 (entry from December 31, 1866).

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , p. 221 (entry from February 10, 1867).

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: The war of the free couples around Rome 1867. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Wanderjahre in Italien. Vol. 4: From Ravenna to Mentana. Leipzig 1871, pp. 195–341.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. With twenty-seven contemporary illustrations. 5th edition, CH Beck, Munich 1997, pp. IX-XVII, here p. XVI; Alberto Forni: The success of Gregorovius in Italy. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 12–41, here p. 28.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 1–11, here p. 8.

- ^ Herbert Rosendorfer : A note on Gregorovius. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries , Vol. 73 (1993), pp. 664-672, here p. 664 ( online ).

- ↑ Dominik Fugger: A life as a private scholar. Ferdinand Gregorovius in his letters to Königsberg. In the S. and Nina Schlüter (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius: Briefe nach Königsberg 1852-1891. Beck, Munich 2013, pp. 7–31, here p. 21.

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben: Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233–271 ( digitized version ), here p. 267.

- ↑ Quoted from Dominik Fugger: A life as a private scholar. Ferdinand Gregorovius in his letters to Königsberg. In the S. and Nina Schlüter (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius: Briefe nach Königsberg 1852-1891. Beck, Munich 2013, pp. 7–31, here p. 26 f.

- ↑ Quoted from Dominik Fugger: A life as a private scholar. Ferdinand Gregorovius in his letters to Königsberg. In the S. and Nina Schlüter (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius: Briefe nach Königsberg 1852-1891. Beck, Munich 2013, pp. 7–31, here p. 26.

- ^ Alberto Forni: The success of Gregorovius in Italy. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. (= Library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78). Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993, pp. 12–41, here p. 25.

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben: Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233-271, here p. 269 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Heinrich Hubert Houben: Ferdinand Gregorovius (afterword). In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. Selection in two volumes with the portrait of the author, two maps and a biographical afterword by Dr. HH Houben. Second volume, 5th edition, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1920, pp. 233-271, here pp. 270 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Angela Steinsiek: The epistolic work of Ferdinand Gregorovius. An inventory. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries , Vol. 97 (2017), pp. 290–315, here p. 315 ( PDF online ).

- ↑ Cesare De Seta: Gregorovius and the polemics about the change in the Roman cityscape after 1870. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78). Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993, pp. 203-216.

- ^ Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 14.

- ^ Friedrich Althaus: Foreword by the editor. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Roman diaries. Verlag der JG Cotta'schen Buchhandlung, Stuttgart 1892, pp. III – XXV, here SV ( digitized version ).

- ^ Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 14.

- ^ Hans Lippold: Ferdinand Gregorovius Masoviae Königsberg . In: Einst und Jetzt, yearbook of the Association for Corpsstudentische Geschichtsforschung , Vol. 5 (1960) pp. 62–71, here p. 62.

- ^ Angela Steinsiek: The epistolic work of Ferdinand Gregorovius. An inventory. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries , Vol. 97 (2017), pp. 290–315 ( PDF online ), here p. 307.

- ^ Herbert Rosendorfer: A note on Gregorovius. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries , Vol. 73 (1993), pp. 664–672, here p. 664 ( PDF online ).

- ^ Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 13.

- ↑ Quoted from Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 9.

- ↑ Dominik Fugger: Redemption through worship and work. Ferdinand Gregorovius and history as an existential experience. In the S. (Ed.): Transformations of the historical. History experience and history writing with Ferdinand Gregorovius. Tübingen 2015, pp. 1–23, here p. 22.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft : The historian as a poet. On the 100th anniversary of Ferdinand Gregorovius' death. In: Meeting reports of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class , Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7696-1564-6 , pp. 1–18 ( PDF online ), here p. 3.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 1–11, here p. 9.

- ^ Heinz Holldack: Victor Hehn and Ferdinand Gregorovius. A contribution to the history of the German conception of Italy. In: Historische Zeitschrift , Vol. 154 (1936), pp. 285-310, here p. 300 f.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Römische Tagebücher 1852-1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 198 (entry from August 16, 1865).

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 1–11, here p. 1.

- ↑ Francis Pomponi: Gregorovius discovered Corsica. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 42–58. Quotes from pp. 43, 54 and 56.

- ^ Angela Steinsiek: The epistolic work of Ferdinand Gregorovius. An inventory. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries , Vol. 97 (2017), pp. 290–315 ( PDF online ), here p. 311.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. With twenty-seven contemporary illustrations. 5th edition, CH Beck, Munich 1997, pp. IX-XVII, here p. IX.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. With twenty-seven contemporary illustrations. 5th edition, CH Beck, Munich 1997, pp. IX-XVII, here SX

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Introduction. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Years of Wandering in Italy. With twenty-seven contemporary illustrations. 5th edition, CH Beck, Munich 1997, pp. IX-XVII, here p. XI.

- ↑ Girolamo Arnaldi: Gregorovius as a historian of the city of Rome: the early Middle Ages. An appreciation. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 117–130, here pp. 120 and 122 f.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft : The historian as a poet. On the 100th anniversary of Ferdinand Gregorovius' death. In: Meeting reports of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class , Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7696-1564-6 , pp. 1–18 ( PDF online ), here p. 9.

- ^ Arnold Esch: Gregorovius as a historian of the city of Rome: his late Middle Ages in today's perspective. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 131–184, here p. 133.

- ^ Arnold Esch: Gregorovius as a historian of the city of Rome: his late Middle Ages in today's perspective. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 131–184, here p. 134.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 1–11, here p. 6.

- ↑ Waldemar Kampf: Origin, reception and impact of the "History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages". In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: History of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages. From V. to XVI. Century. Vol. 4, edited by Waldemar Kampf, Munich / Darmstadt 1976, pp. 7–54, here p. 35.

- ↑ Waldemar Kampf: Origin, reception and impact of the "History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages". In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: History of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages. From V. to XVI. Century. Vol. 4, edited by Waldemar Kampf, Munich / Darmstadt 1976, pp. 7–54, here p. 38.

- ^ Arnold Esch: Gregorovius as a historian of the city of Rome: his late Middle Ages in today's perspective. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 131–184, here pp. 168 and 170.

- ^ Arnold Esch: Ferdinand Gregorovius (1821-1891). Eternal Rome: city history as world history. In: Dietmar Willoweit (ed.): Thinker, researcher and discoverer. A history of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences in historical portraits. CH Beck, Munich 2009, pp. 149-162, here p. 150 f.

- ↑ Waldemar Kampf: Origin, reception and impact of the "History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages". In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: History of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages. From V. to XVI. Century. Vol. 4, edited by Waldemar Kampf, Munich / Darmstadt 1976, pp. 7–54, here p. 17.

- ^ Alberto Forni: Gregorovius, Ferdinand. In: Mario Caravale (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 59: Graziano – Grossi Gondi. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2002.

- ^ Arnold Esch: Gregorovius as a historian of the city of Rome: his late Middle Ages in today's perspective. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 131–184, here pp. 159–164.

- ^ Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 34.

- ↑ Girolamo Arnaldi: Gregorovius as a historian of the city of Rome. An appreciation. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 117–130, here p. 117.

- ↑ Quoted from Hanno-Walter Kruft: The historian as a poet. On the 100th anniversary of Ferdinand Gregorovius' death. In: Meeting reports of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class , Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7696-1564-6 , pp. 1–18 ( PDF online ), here p. 16.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: The historian as a poet. On the 100th anniversary of Ferdinand Gregorovius' death. In: Meeting reports of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class , Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7696-1564-6 , pp. 1–18 ( PDF online ), here p. 16.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: Gregorovius and the view of Rome. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 1–11, here p. 10.

- ↑ Ernst Osterkamp: From the ideal of the "moderate form". Ferdinand Gregorovius as a poet. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 185–202.

- ↑ Markus Völkel: Seeing Rome - the first complete edition of the “Roman Diaries 1852–18889” by Ferdinand Gregorovius. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 59–72, here p. 59.

- ^ Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 16. Quotes from ibid.

- ^ Friedrich Althaus: Foreword by the editor. In: Ferdinand Gregorovius: Roman diaries. Verlag der JG Cotta'schen Buchhandlung, Stuttgart 1892 ( digitized version ), pp. III – XXV, here pp. III f.

- ↑ Jens Petersen: The image of contemporary Italy in the years of travel by Ferdinand Gregorovius. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), pp. 73–96, here p. 76.

- ↑ Markus Völkel: Seeing Rome - the first complete edition of the “Roman Diaries 1852–18889” by Ferdinand Gregorovius. In: Arnold Esch, Jens Petersen (ed.): Ferdinand Gregorovius and Italy. A critical appreciation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1993 (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome, vol. 78), p. 59–72, here p. 59 f.

- ^ The Roman Journals of Ferdinand Gregorovius. Edited by Friedrich Althaus, translated from the second German edition by Mrs. Gustavus W. Hamilton, George Bell & Sons, London 1907 ( digitized ).

- ^ Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 14 f.

- ^ Markus Völkel, Hanno Walter-Kruft: Introduction. In: Römische Tagebücher 1852–1889 , edited by Hanno-Walter Kruft and Markus Völkel. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-34893-9 , pp. 9-40, here p. 15.