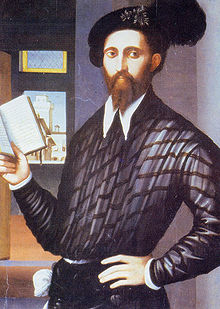

Torquato Tasso

Torquato Tasso (born March 11, 1544 in Sorrento , † April 25, 1595 in Rome ) was an Italian poet of the 16th century, the time of the Counter Reformation . He became best known through the epic La Gerusalemme liberata ( The liberated Jerusalem , translated into German as Gottfried von Bulljon ), in which he describes a fictional battle between Christians and Muslims at the end of the First Crusade during the siege of Jerusalem ; He was also known for the mental illness from which he suffered for most of his life.

Life

Descent and birth

Bernardo Tasso , Torquato's father, was a count from the Tasso family of Bergamo , from whom the line of those of Thurn und Taxis (Italian: della Torre e Tasso ) is derived. Between 1532 and 1558 he worked as a secretary in the service of Ferrante Sanseverino , Prince of Salerno . Tasso's mother was Porzia dei Rossi, the daughter of a noble Neapolitan family with roots in Pistoia .

Torquato Tasso was born in the absence of his father, as he and his master had to take part in the fourth Italian war between Charles V and Francis I from 1543 to 1544 . Of his siblings, Tasso only got to know his older sister Cornelia, since the brother, who was born in 1542 (his name was also Torquato), died the same year he was born.

Childhood and youth

After the father's return to Sorrento in January 1545, the family moved to Salerno in the summer of the same year , where Torquato Tasso spent his first years. When Ferrante Sanseverino came into conflict with Pedro Álvarez de Toledo , Viceroy of Naples , he was ostracized and expropriated. Bernardo Tasso remained loyal to his master and also left the city to take on diplomatic tasks in Ferrara and later Paris . His wife meanwhile moved to her parents in Naples.

In 1552, Bernardo Tasso left his family in Naples, where Torquato was educated in a Jesuit- run school. He learned Latin , Greek, and rhetoric with rapid progress . The early maturity of his intellect and his religious passion aroused a general sensation, so that he achieved fame at the age of eight.

In 1554 the ten-year-old Torquato Tasso was allowed to move in with his tutor Don Giovanni Angeluzzo to live with his father, who meanwhile lived in an apartment in the palace of Cardinal Ippolito II. D'Este . Since his mother's family did not agree with this decision, Porzia Tasso, much to her sorrow, was not allowed to accompany her husband, whereupon she passed away only a few months later. The news that she died in Naples very suddenly and mysteriously, reached Bernardo and Torquato Tasso in 1556. The pain of this event processed Tasso later in the Canzone al Metauro . Bernardo Tasso was convinced that his wife, who is said to have suffered from sudden malaise the night before her death, had been poisoned by her brothers, as they were speculating on a repayment of the dowry. A legal dispute only arose after Cornelia Tasso married that same year against her father's wishes and her right to a dowry from the maternal property was to be examined. As part of the proceedings, Torquato Tasso, like his father before, was declared a rebel and the property of the late Porzia Tasso was divided between her five brothers, her daughter Cornelia and the government. From this period there is a letter from the twelve-year-old Torquato Tasso to Vittoria Colonna 's niece of the same name , in which he asks her for financial support as the wife of the influential García de Toledo Osorio .

In September 1556, Torquato Tasso, accompanied by Don Angeluzzo and Cristoforo Tasso (a second cousin who had come to study in Rome), was sent to Cristoforo's family in Bergamo. Eight months later, Torquato was called to Pesaro by his father , where he lived initially as a guest and later as a servant of Guidobaldo II della Rovere .

Life at the court of Urbino

At the court of Urbino , the young Torquato Tasso became a student companion of Francesco Maria II. Della Rovere , heir to the Duke of Urbino , and was taught by the Italian writer Girolamo Muzio , among others . The aesthetic and literary studies that were in vogue at the time were cultivated in court circles. Bernardo Tasso read the chants of his Amadigi to the Duchess and her ladies or discussed the achievements of Homer , Virgil and Ariost with the duke's librarians and secretaries. Torquato grew up in an atmosphere of cultured luxury and somewhat pedantic criticism. Both of these had a major impact on the formation of his character.

In the spring of 1559 Torquato Tasso took his father on a trip to Venice, where he met Sperone Speroni , Girolamo Ruscelli and Francesco Patrizi da Cherso, among others . The Turkish conquests of Hungary and their frequent attacks on the Italian coast made people think of a new crusade . Torquato, who found the tomb of Pope Urban III in the Cava de 'Tirreni Abbey . and who is said to have been told the story of the First Crusade on that occasion, began to think about a poem on the subject. However, it is not certain whether the fragment that has been preserved was not created closer to Rinaldo . The fragment contains the material of the first three chants of the later Gerusalemme . When Torquato realized the work was going to be very lengthy and difficult, and felt the urge to become famous, he put it aside and began working on a simpler one that would later become the Rinaldo .

Academic years

In 1560 Torquato Tasso began studying law in Padua , but the following year he only attended lectures in philosophy and language skills with Francesco Piccolomini (1520–1604) and Carlo Sigonio . In those years Tasso also belonged to a private circle of scholars around Sperone Speroni. Torquato did not necessarily pursue his studies persistently until his father allowed him to enroll in philosophy and rhetoric after a year . Encouraged by his friends, Tasso continued to work on his Rinaldo .

In the summer of 1562, the narrative poem was published with a dedication to Luigi d'Este , Bernardo Tasso's master at the time. The poem impressed little by its plot, style and editing, but by its originality, so that its author was considered the most promising poet of his time, even though he was not even 18 years old. The flattered Bernardo allowed the epic to be printed.

In November 1562 Tasso moved to Bologna , where he often attended private literary academies. He spent the summer with his father in Mantua , where he worked as Guglielmo Gonzaga's secretary . At the beginning of 1564 Torquato Tasso ran out of funds for unknown reasons, which he needed to continue his studies. Around the same time, he was accused of acting as a pasquillant , which led to the confiscation of all his papers and ultimately to a lawsuit from which the files have been preserved. Tasso fled to Modena to Tommaso Rangone , an old patron of his father. From there he wrote a letter to the papal legate in Bologna, in which he admits to having recited the diatribes, but does not comment on the author. In March 1564, Tasso returned to Padua at the invitation of Prince Scipio Gonzaga . He became a member of the Academia degli Eterei founded by Gonzaga under the name Pentito and resumed his interrupted studies at the university. It is not known whether Tasso ever completed his studies. During his stay in Padua he wrote his first lyric pieces. Some were inspired by Tasso's first love for Lucrezia Bendidio , a young lady from a noble Ferrarese family. He wrote the others for Laura Peperara , whom he fell in love with during his vacation in Mantua.

Ferrara

After finishing his studies in the summer of 1565, Tasso went to Ferrara to work as court poet in the service of Cardinal Luigi d'Este. There he met Giovan Battista Nicolucci and Giovanni Battista Guarini , among others . At court he also had the opportunity to continue working on the Gerusalemme and completed the first six Canti of Gottifredo in the course of 1566 .

On September 5, 1569, Bernardo Tasso died in Ostiglia in the presence of his son . In 1570 Tasso traveled with other courtiers to Paris , where they lived in the Chaalis monastery . The cardinal himself did not arrive until February 1571 to attend the wedding festivities for Charles IX. to participate.

His very open manner of speaking and his habitual lack of tact led to arguments with the cardinal. It is possible that there was a minor incident with King Charles IX. gave, whose tolerance towards the Huguenots Tasso criticized. So he left France as quickly as possible on March 19th. According to another version, Tasso was dismissed because the cardinal lacked money. In his Dialogue Cattaneo (1585) Tasso mentions that he met the poet Ronsard during his stay in France .

On April 15 In 1571 he returned for a few days to Ferrara back, then he traveled to Rome and from there to Pesaro and Urbino , where he Lucrezia d'Este met who previously held the Prince in Francesco Maria II. Della Rovere had married . With her he returned to Ferrara in September. From January 1572 he took service under Duke Alfonso II , the brother of Cardinal Luigi d'Este, initially without a clearly defined activity, from 1576 officially as a historian of the court, and became increasingly famous under this.

In January 1573 Tasso followed the Duke to the festivities for Pope Gregory XIII. to Rome and in a few months composed the Aminta , a pastoral drama that he presumably presented to the court of Ferrara in the spring or summer. The following year Tasso was appointed professor of geometry in Ferrara. During the carnival season, Tasso traveled to Pesaro, where he read from the Aminta and took part in literary disputes with Jacopo Mazzoni . In July, Tasso accompanied the Duke to Venice to help Henry III pass through . to be present, who returned from Poland to take possession of the crown of France.

La Gerusalemme Liberata

Tasso continued to work on his main work, La Gerusalemme Liberata , which he completed in April 1574 after having worked on it for over 15 years. He read it to the Duke and Princesses the following summer. The most pleasant time of his life was over, his greatest works had already been written when he was confronted with unexpected problems. Instead of publishing the work immediately, he felt unsettled. He sent manuscripts of the Gerusalemme to various sizes of his time - writers, theologians, philosophers - to obtain their opinions. Tasso asked them to express their criticism and wanted to accept their suggestions as far as they corresponded to his ideas. In May he went to Padua and Vicenza and asked the scholar Gian Vincenzo Pinelli to examine the work. Then in September 1575 to Rome, where he submitted the epic Scipio Gonzaga , Flaminio de 'Nobili , Silvio Antoniano , Pier Angelis Bargeo , Sperone Speroni and, in Florence, to the famous writer Vincenzo Borghini .

While the gerusalemme was generally praised, details should be changed. There was criticism of the plot, the title, individual episodes, the choice of words and the basic moral tone. A friend remarked that the Inquisition would not tolerate the supernatural parts, another wanted the most magical passages to be expanded - the love stories of Armida, Clorinda and Erminia. Some believed that the epic form chosen by Tasso did not match the emotional content of the poem and advised a revision.

Tasso, already heavily challenged by his studies, the strenuous life at court and his work as a man of letters, could not cope with the additional exertion and his health began to suffer. He complained of headaches, suffered from malaria-like chills and wanted to leave Ferrara. So he began negotiating with the court of Florence , which angered the Duke of Ferrara, who hated nothing more than when a courtier abandoned him for a rival duke. He suspected that if he let Tasso go, the Gerusalemme would be dedicated to Tasso's new masters, the Medici . So he decided to deny Tasso permission to leave the farm.

Beginning decline

1576 Tasso visited Modena in April for the Easter celebrations ; when he returned to Ferrara in May he became seriously ill. From 1575 to 1577 his health deteriorated noticeably. He suffered from deep depression and sudden melancholy . He was hostile to the courtiers because of his success at court. His easily excitable and suspicious temperament, very sensitive to insults, encouraged hostilities. Tasso fell victim to delusions, thought that his servants were abusing his trust, feared they had been betrayed to the Inquisition , and daily expected to be poisoned. Over time he developed a kind of paranoia . Tasso probably suffered from a mental illness from 1575 onwards, which, without affecting him physically, made him a problem for his patrons due to his difficult to tolerate behavior. Today it is believed that this disease was schizophrenia .

On September 7, 1576, when it seemed as if Tasso had recovered a little from his suffering, he was assaulted in broad daylight in a public square in Ferrara by Ercole Fucci and his brother Maddalo, both members of the court. During the subsequent brawl, the poet was hit very badly in the head with a stick, seriously injuring him. The culprit fled and thus escaped the inquiries the prince had made. The cause of the dispute is said to have been either the courtiers' envy of Tasso's success or the fact that Maddalo had spoken too openly about a love affair. Indignant, Tasso then went to Modena, where he made the acquaintance of the beautiful and famous poet Tarquinia Molza , in whose honor he wrote a few verses. At the end of January 1577 he went back to Ferrara, more precisely to Comacchio , where the court was staying at that time.

His religious scruples also increased. In June 1575 he had to answer at his own initiative before the Inquisitor of Bologna because he accused himself of heresy , in June 1577 before the Ferraras. Religious zeal was dangerous in Ferrara, where Calvinist ideas were widespread. The absolution that the inquisitor gave him did not reassure Tassos. He believed that it was only out of pity that they let him persist in his mistaken belief.

On the evening of June 17th, when he confessed his torment to Princess Lucrezia, Tasso imagined that a servant passing by was spying on him. He stabbed him with his knife. The Duke had him locked up in a small room inside the castle and made sure that Tasso was looked after. A little later he took him to his pleasure palace Belriguardo in the hope that the diversions in the country would have a beneficial effect . What happened there is unknown. Some biographers claim that a compromising liaison with Leonora d'Este came to light and Tasso went insane to protect her honor. What is certain is that he was sent back to Ferrara almost immediately and had to go to the Franciscan convent there, apparently with the declared intention of restoring his health. He stayed there for some time, constantly afraid of being poisoned by the drugs administered to him. He believed he had fallen out of favor with the duke; the thought that the prince would have him murdered never let go of Tasso.

There is no evidence that his behavior arose from an excessive passion for Leonore d'Este. Contrary to his image of a tyrant, the duke showed considerable leniency. He was inflexible and poorly understanding, as in need of recognition as was to be expected of a man of his rank at the time. He was less cruel towards Tasso, he was certainly not the monster that was later made of him. The further course of relations confirms this.

On the night of July 25, 1577 Tasso destroyed the door of his cell and fled to Ferrara. He disguised himself as a farmer and walked to his sister in Sorrento. Tasso appeared before her in the disguise of a shepherd, as described in the letter of November 14, 1578, and told her about the alleged death of Tasso, as Manso relates, to find out what effect the circumstance would have on her. After he had lifted his disguise, she welcomed him with joy. At the end of January 1578, Tasso felt the desire to complete his poems and went to Rome for it. He found accommodation at first with Cardinal Luigi d'Este, a little later with Giulio Masetti , the ambassador of Ferrara.

Inconsistency

In Rome, Tasso, tired of court life, longed for the family environment of Ferrara. He wrote a humble letter asking if he could return to Ferrara. Alfonso granted this on condition that Tasso underwent medical treatment for his melancholy. On his return in mid-April 1578, Tasso was taken back by the ducal family. If his old illnesses had not been revived, life in Ferrara would surely have regained its former glory. However, there were always moments when he was prone to irritability, moodiness, suspicion, hurt vanity and violent outbursts.

In the first days of July Tasso fled again, traveling through Mantua , where he sold what he owned, and through Padua, Venice and Pesaro, where he was received again by Duke Francesco Maria, his childhood companion. In September he secretly left the duchy and went to Piedmont . He reached the gates of Turin on foot , where, as he had no confirmation of his health (essential in times of plague), the guards did not let him in. Angelo Ingegneri , a Venetian scholar whom Tasso met in Ferrara, made sure that Tasso was admitted anyway. Prince Charles Emanuel I offered him to enter his service, as did the Archbishop Cardinal Giulio della Rovere and the Marquis Philippe d'Este, son-in-law of Duke Emmanuel-Philibert of Savoy .

Wherever he went, his name and poetic talent made him welcome. But soon (in November) Tasso grew tired of society. He was still drawn to Ferrara. So he negotiated again with the prince and in February 1579 the poet was once again accepted into the castle. Alfonso was about to host his third marriage, the one with Princess Margarita of Mantua. He had no children from his first two marriages, and if there was no heir, the possibility existed that his rank might go to the Holy See (as actually happened later). The wedding celebrations, during which Tasso reached the court, did not give the aging groom an opportunity to be very happy with the return of his protégé. Alfonso was not happy about the need for a third marriage and his expectations for the future of his marriage were not very hopeful. Tasso, too preoccupied with his own worries and feelings, could not muster the necessary attention to his master's problems. Nevertheless, he asked for an audience with the Duke, which he was refused. He felt treated below his rank. The princesses didn't want to see Tasso either. On the evening of March 11th, he and Cornelio Bentivoglio, the duke's captain, spread insults against conditions at court. When Tasso was brought before the court a little later, he was the victim of a violent delusional attack, so that he was seized and sent to the insane asylum of St. Anna, where he remained - for more than seven years - until July 1586. After much hope, Duke Alfonso believed that Tasso was definitely crazy and that St. Anna was the safest place for him.

Leonora d'Este

A mystery in Tasso's life is why he was drawn back to the court of Ferrara again and again. One possible cause would be an unfulfilled love for Leonora d'Este. However, as already stated, there is no evidence for such a love affair. Tasso's relationship with Leonora was no more intimate or passionate than that with her sister Lucrezia. The poems he had dedicated to some of the other women were no less respectful or less passionate than those he dedicated to Leonora. Had Tasso violated Leonora's honor, the Duke would certainly have had him killed. Society promoted retaliation in the event of a violation of the honor of a lady of her rank. In any case, Tasso did not behave like a loyal lover towards Eleonora; especially when he returned to Ferrara in 1578 and 1579, he showed no undue efforts to regain familiarity with Eleonora d'Este. So if Tasso actually had a secret relationship with Leonora all his life, it is hidden in the impenetrable fog of time.

In prison

Tasso was trapped for more than seven years. However, after the first few months of his incarceration, he received spacious rooms, was allowed to take his meals at the Duke's court, received visits from his friends (among others he was visited by Michel de Montaigne in 1581 ), and was accompanied by supervisors from his circle of acquaintances who were responsible for him Excursions were permitted and he was allowed to exchange letters freely. The letters he wrote from St. Anne to the princes of Italy, to his favored patrons, and to men of the highest reputation in art and culture, are the most valuable source of information on his health and mental state. He always spoke respectfully, almost lovingly, of Duke Alfonso. Critics claimed Tasso kissed the hand that was chastising him in the hope that he would be released from prison; but this opinion is controversial. It appears from the letters that he believed he was suffering from a serious mental illness. He continued to have to be monitored as he suffered from dangerous seizures from time to time. That in addition to long periods in which he was spared.

Tasso was very productive during his captivity. He wrote a variety of dialogues on philosophical and ethical topics. Apart from a few odes and sonnets, some of which were commissioned and of interest only in terms of rhetoric, he wrote poems. Everything he wrote during this period was kept by those who, while obviously mistaking him for a madman, were nonetheless very interested in his works.

In 1580 Tasso heard that parts of his Gerusalemme had been published without his permission and without his corrections: Celio Malaspina published 14 hymns of the Gerusalemme in Venice. Angelo Ingegneri , who had a complete manuscript, published an edition in Parma and another in Casalmaggiore the following year . In the six months that followed, the press issued seven different editions. Still imprisoned in the madhouse of St. Anna, Tasso had no influence whatsoever on his editors and did not earn a penny on his masterpiece, which put him artistically on a par with Petrarch and Ariostus . A competing poet of the court of Ferrara, Giovanni Battista Guarini , took over the task of revising and editing Tasso's verses in 1582, who had to allow his odes and sonnets, personal poems and occasional greetings to be collected and corrected without his being in his cell could exercise his influence in cases of doubt.

A few years later, in 1585, two Florentine members of the Accademia della Crusca declared war on the Gerusalemme . Tasso felt obliged to respond to the critics, and did so with such moderation and sophistication that it seemed as if he were not only an outstanding man of honor, but also in full possession of his intellectual powers.

Tasso allegedly behaved pathetically and irritably in captivity, but never ignoble. He showed indifference to his work and generosity in dealing with his critics. It seems strange that he always tried to accommodate his two nephews, the sons of his sister Cornelia, at court. He sent one to the Duke of Mantua, Guglielmo I of Gonzaga, and the other to the Duke of Parma, Ottavio Farnese .

Freedom regained

The Prince of Mantua, Vincenzo Gonzaga , often came to Ferrara to see his sister, the new Duchess. He also visited Tasso in his prison. In July 1586, he proposed to the duke, with the promise to bring him back to Ferrara immediately at his request, to take Tasso with him. Alfonso agreed and on July 13th the poet was allowed to leave his prison to go to Mantua. He lived for a while in freedom in the hustle and bustle of the court, occupied himself with his poems and ended a tragedy that had already started under the title Galeatto, King of Norway , which he later renamed King Torrismondo . In 1587 he went to Bergamo, where he had relatives and enjoyed the warm welcome in his hometown. But after a few months he became dissatisfied again. Vincenzo Gonzaga, who replaced his father as Duke of Mantua, had little leisure to look after the poet. Tasso felt neglected. In October 1587 he fled to Modena , then traveled through Bologna and Loreto to Rome, where he took up quarters with his old friend Scipione Gonzaga, who was now the Patriarch of Jerusalem , on November 3rd. The following year he wandered to Naples in the hope of seeing his sister again and, after it was found that his sister had died, wrote a melancholy poem there in March about Monte Oliveto . He lived as a guest of various distinguished gentlemen. Particularly noteworthy is Manso, who became his first biographer.

On November 25, 1589, Tasso returned to Rome, where he stayed with Scipione Gonzaga, who had meanwhile been appointed cardinal. In Rome, Tasso lived in the Palais on Via della Scrofa, which is now called Palais Negroni-Galitzin.

Because of his eccentric behavior, he was soon thrown out the door. Tasso fell ill and stayed with the monks of the monastery on Monte Oliveto until November. During this time his mental state deteriorated noticeably. Because of this, he went to a hospital in Bergamo a month later. When he left it again in 1590, the patriarch took him in again. But Tasso's restless spirit drove him to Florence on April 15th, where he was received in a princely manner by Grand Duke Ferdinand I. In September he traveled to Rome again.

Vincenzo Gonzaga had also invited him to come to his court. After lengthy negotiations, Tasso accepted and reached Mantua on March 17th, 1591. All the while he continued to go through his manuscripts and forge new verses. In August the poet fell seriously ill; in November he accompanied the duke to Rome, to Innocent IX. to greet the new Pope.

In January 1592 he was invited by Matteo di Capua , Prince of Conca , to come to Naples, where he began a new poem, Il Mondo creato , which was only published posthumously in 1607. In April, when Tasso returned to Rome, he had to go to Mola de Gaëta for a few days because the famous bandit Marco de Sciama was in the area. In Rome he lived with Vincenzo Gonzaga until June, then with Cinzio and Pietro Aldobrandini , the nephew of Pope Clement VIII , who had ascended the Holy See in 1592. In 1593 he dedicated the Gerusalemme conquistata , a revised version of the Gerusalemme liberata, to both of them . Everything that the epic of earlier years had made appealing was rigorously eradicated by him. In the same year a prose piece appeared in Italian blank verse , Le Sette Giornate , a somber description of the first chapter of Genesis that has not survived.

Papal Appreciation and Death

Tasso's health deteriorated and his skills stagnated. In June 1594 he found asylum with the monks of San Severino. In November the Pope called him to Rome to crown him on the Capitol with the crown of the poet , with which Petrarch had previously been honored. Tasso reached Rome seriously ill. In addition, the coronation ceremony was postponed because Cardinal Aldobrandini was also ill. He was given pleasant days, the Pope made sure that Prince Avellino, who owned Tasso's inherited fiefdoms, paid an annual pension to Tasso, but his suffering worsened.

At the beginning of April 1595, Tasso went to the monastery of Sant 'Onofrio to be able to recover there. Allegedly, as he got out of his carriage, he said to the prior of the monastery that he had come to die here. The Pope sent him his personal physician Cesalpino. On April 25, 1595, one day before the planned coronation of the poet, Torquato Tasso died in Sant'Onofrio. The Pope arranged for Tasso to have a solemn funeral. At his own request, he was buried on the monastery grounds. Later, as the Latin inscription on the floor indicates, his bones were moved from the original grave to the 19th century monument in the last side chapel on the left.

Works

- Torquato Tasso: Gerusalemme liberata . Edited by Lanfranco Caretti, Einaudi, Turin 1993.

- German translations of the Gerusalemme liberata (selection):

- Gottfried von Bulljon von Diederich von dem Werder , ed. Gerhard Dünnhaupt , Tübingen 1974 (reprint of the 1626 edition).

- Attempt of a poetic translation of the Tasso heroic poem called: Gottfried, or the Liberated Jerusalem by Johann Friedrich Koppe . Leipzig 1744, online .

- Befreytes Jerusalem , 2 volumes, translated by August Wilhelm Hauswald , Görlitz 1802, first volume , second volume .

- JD Gries : Torquato Tasso's Liberated Jerusalem , 4 parts, Jena 1800–1803, revised version 1810; transferred in punching (like the original); Text on https://www.projekt-gutenberg.org/tasso/jerusalm/index.html

- W. Heinse: The liberated Jerusalem , 4 vols., 1781; Prose translation

- E. Staiger: Tasso, Torquato: Works and Letters. Translated and introduced by Emil Staiger, Munich 1978 in Winkler thin-print library of world literature; in it transposed in blank verse 'The Liberation of Jerusalem' (note: Staiger chooses the title 'The Liberation of Jerusalem' according to the content of the epic and not, as usual, 'The Liberated Jerusalem'.)

- German translations of the Gerusalemme liberata (selection):

- The shepherd's game Aminta (1573) is considered the most beautiful pastoral poetry in Italian. Pastoral drama, simple plot, captivates with its lyrical charm.

- German translations:

- The famous Jtaliaenian poet Torqvati Taszi Amintas or forest poems by Michael Schneider , Hamburg 1642.

- Amyntas, shepherd poems by the famous poet Torquati Tassi by Johann Heinrich Kirchhoff , Hanover 1742, online

- German translations:

- The knight epic Rinaldo (1562).

- Small prose works.

- Torquato Tasso left around 1700 letters.

In the poetry u. a. treated by Goethe : Torquato Tasso 1790, Lord Byron 1819, Ernst Raupach 1833, Paolo Giacometti 1855.

Statues and monuments

- Tasso oak in Rome on the Rampa della Quercia south of the monastery of Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo : the black weathered torso of an ancient oak, supported by a metal frame, whose shadow the poet used to seek out.

- Statue of the poet in the Piazza T. Tasso in his native Sorrento .

- Marble bath by Gustav Blaeser in the poets' grove in front of the west side of the Charlottenhof Palace , called "Siam", in the park of Sanssouci / Potsdam .

- Statue of the poet on the Piazza Vecchia in Bergamo, in front of the Palazzo della Ragione .

literature

- Claudio Gigante: Tasso, Torquato. In: Raffaele Romanelli (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 95: Taranto – Togni. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2019.

- Achim Aurnhammer (Ed.): Torquato Tasso in Germany. Its effect in literature, art and music since the middle of the 18th century. de Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 1995, ISBN 3-11-014546-4 . (Sources and research on literary and cultural history, 3 (= 237))

- Winfried Wehle : Torquato Tasso. Language knight. Annual gift of the Frankfurt Foundation for German-Italian Studies, Frankfurt a. M. 1997. PDF

- Umberto Bosco: Tasso, Torquato. In: Enciclopedie on line. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1937.

- Achim Aurnhammer: Review of Aminta. Favola boschereccia. A shepherd's game. Italian and German, trans. by János Riesz . Reclams Universalbibliothek , 446. In: Romanische Forschungen , Volume 110, H. 1, 1998, S. 157–159 (including a comparison with the translation by Otto von Taube )

Web links

- Literature by and about Torquato Tasso in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Torquato Tasso at Zeno.org .

- Works by Torquato Tasso in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Torquato Tasso on the Internet Archive

- Works by Torquato Tasso : text, concordances, word lists and statistics

- Uwe Japp: Suffering and transfiguration. Torquato Tasso as a representative poet after Goethe (PDF file; 101 kB)

- Jutta Duhm-Heitzmann: April 25, 1595 - Anniversary of the death of Torquato Tasso WDR ZeitZeichen on April 25, 2020 (Podcast)

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Rosanna Morace: Tasso, Bernardo . In: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani . tape 95 . Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2019 (Italian, treccani.it ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Claudio Gigante: Tasso, Torquato . In: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani . tape 95 . Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2019 (Italian, treccani.it ).

- ↑ Maria Rafaella De Gramatica: De 'Rossi, Portia . In: Dizionario biografico degli italiani . tape 39 : Deodato-Di Falco. Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana, Rome 1991 ( treccani.it ).

- ↑ a b Evi Zemanek: The face in the poem. Studies on the poetic portrait . Böhlau, Cologne 2010, p. 147.

- ↑ For current translations, see the review under literature: Janos Riesz, Otto von Taube

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tasso, Torquato |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 11, 1544 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sorrento |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 25, 1595 |

| Place of death | Rome |