Chestnut banquet

The Banquet of Chestnuts (also: chestnut ball , chestnut ballet or chestnut orgy ) was a supposedly a sex orgy connected banquet that Cesare Borgia on 31 October 1501 in the Apostolic Palace in Rome is said to have organized, in the presence of his sister Lucrezia and his father, of Pope Alexander VI. The main source for the event is the Liber notarum , the ceremonial diary of Johannes Burckard , from which it is the most widely noticed passage. Today's historians doubt that the banquet took place in the form described by Burckard.

swell

In the main source, the Liber notarum Johannes Burckards, the German master of ceremonies of Pope Alexander VI, it says in the original Latin text:

“Dominica, ultima mensis octobris […] In sero fecerunt cenam cum duce Valentinense in camera sua, in palatio apostolico, quinquaginta meretrices honeste, cortegiane nuncupate, que post cenam coreaverunt cum servitoribus et aliis ibidem existentibus, primo in vestibus suis, deinde nude. Post cenam posita fuerunt candelabra communia mense in candelis ardentibus per terram, et projecta ante candelabra per terram castanee, quas meretrices ipse super manibus et pedibus, nude, candelabra pertranseuntes, colligebant, papa, duce et d [omna] Lucretia et sorore suibus present . Tandem exposita dona ultima, diploides de serico, paria caligarum, bireta et alia pro illis qui pluries dictas meretrices carnaliter agnoscerent; que fuerunt ibidem in aula publice carnaliter tractate arbitrio presentium, dona distributa victoribus. "

In the German translation by Ludwig Geiger [with the addition of the words not translated by Geiger in square brackets]:

“On Sunday, on the evening of the last October 1501, Cesare Borja [the Duke of Valentinois] held a feast in his room in the Vatican with 50 honorable prostitutes, called courtesans, who after the meal with the servants and the other people present danced, first in their clothes, then naked. After the meal the [ordinary] table candlesticks with the burning candles were placed on the floor and chestnuts were strewn around them, which the naked prostitutes picked up on hands and feet between the candlesticks, the Pope, Cesare and his sister Lucretia [being present and ] watched. Finally, prizes were offered, silk overcoats, shoes, berets, etc. for those who could most often perform the act with the prostitutes. The spectacle took place here in the hall and the prizes were given to the winners according to the judgment of those present. "

The other sources for the chestnut banquet are less detailed or less decorated; Chestnuts are no longer mentioned. On November 4, 1501, the Florentine envoy Francesco Pepi reported: “On All Saints' Day and All Souls Day the Pope did not come to St. Peter's Church and the papal chapel because of an ailment that did not prevent him from attending Sunday during the vigil before All Saints' Day to spend the night up to the twelfth hour with the Duke [Cesare Borgia], who had brought singers and courtesans to the palace that night, and they spent the whole night with merrymaking, dancing and laughter. "

In the chronicle of Francesco Matarazzo from Perugia there is also a record of a dance festival in the Vatican; there it then goes on to say: “And as if that had not been enough, when he returned to the hall he [the Pope] had all the lights extinguished, and then all the women who were there, and as many men as well, all went Clothes off and there was a lot of amusement and play. "

The so-called Savelli letter, a letter hostile to the Pope, which Burckard cites in full in the Liber notarum, dates from November 15, 1501. This anonymous letter is said to have been written in the royal camp in Taranto. His addressee is Baron Silvio Savelli, exiled from Rome, in his exile at the court of King Maximilian . The hateful letter presents all the suspicions that have ever circulated in Rome against the Borgia as proven facts, including the chestnut banquet: “Who would not shudder to enumerate the appalling monstrosities of debauchery that are already evident in his [Alexander's] house Contempt for shame before God and the people who are committed? All the desecrations, the incests, the meanness of boys and girls, the clutches and competitions, the brothels and whore houses - none of this would even come off the lips. On November 1st, on All Saints Day, 50 Roman whores were invited to the palace for a feast and presented the meanest and most hideous spectacle; and so that the examples of the incentive were not missing, in the next few days the pope and his children watched the public spectacle of a mare, on which one let loose stallions in heat in order to drive them into anger and frenzy ”.

Finally, there are two sources that are not directly related to this event, but Pope Alexander VI. in connection with debauchery in the Vatican: On the one hand, this is a letter from Agostino Vespucci to Niccolò Machiavelli , which dates as early as July 16, 1501 and claims that the Pope fetched 25 or more women into his palace every evening, thereby making him one Brothel being transformed. The Venetian envoy Giustiani reported on December 30th, 1502 to his homeland: “Yesterday I dined with His Holiness in the palace and stayed until the early morning with the conversations that form the regular amusements of the Pope and in which women take part without themselves the pontiff cannot think of any feasts. Every evening he lets girls dance with him and gives parties of a similar kind, with courtesans figuring. "

Reception and controversy about historicity

Authors critical of the church used the chestnut banquet as an example of the immorality of the Catholic Church. Otto von Corvin quotes Burckard's report in his Pfaffenspiegel , a well-known anti-clerical work of the 19th century. Karlheinz Deschner mentions the chestnut banquet or "whore tournament" in his criminal history of Christianity , and also considers the number of 50 courtesans in view of the 50,000 prostitutes that should have been there in Rome at that time to be too high, but leaves the question of actual historicity open ("Are they [the tournaments] just propaganda legends? [...] Whatever.").

Burckard translator Ludwig Geiger spoke out for the credibility of the chestnut banquet in the form described by Burckard with regard to the parallel traditions. Enrico Celani, editor of Burckard's Liber notarum in the original Latin version, does not want to doubt the report either and refers to Burckard's well-informed reporting without polemics and resentment.

The Catholic church historian Peter de Roo developed in his five-volume work in defense of Pope Alexander VI. the theory that there might have been a feast in Cesare Borgia's private apartments in the Vatican; then an exaggerated rumor about it was recorded in the chronicle of Francesco Matarazzo, and only then was the report entered retrospectively by someone else in Burckard's diary. Such theories of an interpolation (also represented by A. Pieper before de Roo in 1893) are possible because, for the most part, Burckard's diaries no longer exist - with the exception of a fragment that extends from August 1503 to May 1506. So it can no longer be checked whether the chestnut banquet was already included in Burckard's autograph from 1501. Ludwig Geiger, however, opposes the assumption of an interpolation: The episode of the chestnut banquet can already be found in the oldest copies of Burckard's diaries. Reinhardt and Neumahr also regard the passage as most likely not interpolated.

Nevertheless, Volker Reinhardt evaluates Burckard's report on the chestnut banquet critically: The reader Burckard had worked his way through cumbersome descriptions of church festivals in order to then seamlessly come across this "group sex in the Vatican" and a "All Saints' Day" converted into the "All Whores Festival"; that explains the shocking and surreal effect the scene has on readers. But it is not at all like Alexander VI, who gave a lot to the intercession of the saints, to ritually tarnish their festival. In addition, Cesare Borgia's trademark was not display, but secrecy, since publicly attested piety could have shaken the foundations of Borgia power. But 50 “courtesans optimally networked through their trade”, like the victorious “competitors of the opposite sex”, could hardly have been silenced. Reputation researchers were also at work at precisely that time to investigate Lucrezia Borgia's reputation; a real orgy would only have endangered Lucrezia's marriage to Alfonso I d'Este and thus “a strategic goal of considerable importance”. Burckard was apparently not present at the orgy described and probably took over the story from a news source hostile to Borgia.

For Ludwig von Pastor, the historical core of the chestnut banquet remains a “scandalous dance festival”, which one can hardly doubt in view of the report by the Florentine envoy (Pepi). Bradford also considers Francesco Pepi's report (see sources above) to be credible and even harmless: Courtesans may well have been invited to Cesare Borgia's dinner, as they were “an essential part of any lively, informal society in Rome in the 15th and 16th centuries “Were, as one can see from Benvenuto Cellini's autobiography. Neumahr is also thinking of an actual banquet, which is then decorated with a lot of joy in telling stories.

According to Marion Hermann-Röttgen , the chestnuts in Burckard's story could actually be based on folk customs for the celebration of the nut harvest, which may have been played out at the festival, such as B. Nut cones. Hermann-Röttgen also considers whether Burckard's portrayal could be related to the belief in witches at the time: The chestnut banquet, as Burckard describes it, corresponds structurally to a witch's sabbath . Witch orgies are preferred on Christian holidays in order to increase the unholy. This is already claimed in the Hexenhammer , which Burckard probably knew. In addition, according to descriptions from 1233 ( Bull of Gregory IX. ) And from 1475 (report by the Palatinate court chaplain Matthias von Kemnat ), the lights would be extinguished at such orgies after dinner and then “the most heinous fornication” took place. Hermann-Röttgen therefore comes to the conclusion that in Burckard's sober descriptions, which are presented without emotion or interpretation, reality and superstitious topoi are nevertheless merged with one another.

Theater, music and television

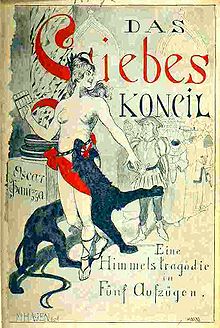

The German writer Oskar Panizza processed in his satirical drama The Love Council (1894), which included the debauchery of Alexander VI. The theme is also the chestnut banquet: in the second act he lets twelve courtesans appear who, at a signal, throw off their robes and then fight for chestnuts that are thrown into the middle of the room. Prizes are then given to the girls depending on the number of chestnuts collected. Then there are athletes wrestling with each other, with each winner choosing one of the courtesans and disappearing behind the stage with her. Panizza, who was charged with blasphemy for this drama and sentenced to one year solitary confinement, came back to this scene in the print version of his defense speech: There he quoted Burckard's entry on the chestnut banquet verbatim in a footnote to indicate that the scene was in his play was much less bad, out of consideration for the performance, but not for the feeling of the Catholics.

Under the name Der Kastanienball - The Fall of Lucrezia Borgia , the music producer Stefan F. Winter performed an “ improvised cabaret opera” accompanied by jazz music at the Prinzregententheater in Munich . Texts by Machiavelli, Luther and Goethe were used as a basis. This “surrealist audio film” with music by Harold Arlen and Jean-Louis Costes , among others , was also recorded on CD.

In 2007 an Italian band called Il Ballo delle Castagne (“The Chestnut Ball”) was founded, whose music style combines hard rock , new wave , progressive and gothic .

In the US historical-fictional television series The Borgias , an episode (season 3, episode 4) is called The Chestnut Ball (in the original: The Banquet of Chestnuts ; first broadcast on May 5, 2013). Contrary to what all historical evidence suggests, the chestnut banquet there is arranged by Giulia Farnese and presented as a trap to make members of the college of cardinals open to blackmail.

literature

- Sarah Bradford: Cesare Borgia. A life in the Renaissance. German by Joachim A. Frank. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1979, ISBN 3-455-08898-8 .

- Ludwig Geiger : Alexander VI. and his court. According to the diary of his master of ceremonies Burcardus . Robert Lutz publishing house, Stuttgart approx. 1913.

- Marion Hermann-Röttgen : The Borgia family. Story of a legend. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1992, ISBN 3-476-00870-3 . There especially pp. 53–61: The chestnut ball .

- Uwe Neumahr: Cesare Borgia. The Prince and the Italian Renaissance. Piper, Munich / Zurich 2007, ISBN 978-3-492-04854-5 .

- Volker Reinhardt : Alexander VI. Borgia. The creepy Pope. 2nd Edition. Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62694-4 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Hermann-Röttgen: The Borgia family. P. 54.

- ↑ Johannis Burckardi Liber notarum , a cura di Enrico Celani, Volume 2 (= Rerum Italicarum scriptores, Raccolta degli storici Italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento, ordinata da LA Muratori 32,1,2), (published in several fascicles, here: Fasc. 104 / Fasc. 9 of vol. 32,1) Città di Castello: Lapi, 1912, p. 303. - An older edition of the Latin text can be found in Louis Thuasne (ed.): Johannis Burchardi… Diarium sive rerum urbanarum commentarii , Vol. 3 (1500–1506), Paris: Leroux, 1885, p. 167.

- ↑ In the original Latin text (see above) there is literally only “the Duke of Valentinois” (dux Valentinensis) , which means Cesare Borgia.

- ↑ The word is missing in Geiger's translation, but is in the Latin original ("communia") and must be supplemented accordingly, cf. also the translation by Reinhardt: Alexander VI. P. 210.

- ↑ Geiger: Alexander VI. and his court. P. 315.

- ↑ See Bradford: Cesare Borgia. P. 205.

- ↑ The original text after Arch. Stor. ital. XVI, p. 189, is quoted in Liber notarum ed. Enrico Celani (as note 2), p. 303 with note 1: “ In questi dì et de Sancti et de Morti el papa non è venuto in San Piero e in Cappella per la scesa hebbe a questi dì, quale benchè lo impedisce da questo, non però lo impedì domenica notte per la vigilia d'ognisanti vegliare infino a XII hore con il duca, quale haveva facto venire in Palazo la nocte ancore cantoniere, cortigiane, et tucta nocte stierono in vegghia et balli et riso . "

- ^ Bradford: Cesare Borgia. P. 207.

- ↑ The report is also reprinted in Will Durant: Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit. Volume 15: The Renaissance: Italian Panorama II, the Roman Renaissance. Geneva approx. 1978, p. 313.

- ^ German translation by Geiger: Alexander VI. and his court. Pp. 320-328.

- ↑ Geiger: Alexander VI. and his court. P. 328.

- ^ Hermann-Röttgen: The Borgia family. P. 62.

- ↑ See Reinhardt: Alexander VI. P. 213.

- ↑ Geiger: Alexander VI. and his court. P. 324.

- ↑ The episode with the mares is also described by Burckard in his diary on November 11, 1501; see. Bradford: Cesare Borgia. P. 206 f. with quote.

- ↑ Liber notarum ed. Enrico Celani (as note 2), p. 303 with note 1. There the following original quote from the letter to Pasquale Villari, Niccolò Machiavelli ei suoi tempi illustrati con nuovi documenti. Volume 1: Florence 1877, p. 558: Restavansi dire che si nota per qualcuno che dal papa in fuori, che vi ha del continuo il suo greggie individuellecito, ogni sera XXV femine e più, da l'Avemaria ad un hora, sono portate in palazo, in groppa di qualcheuno, adeo che manifestamente di tutto il palazo e factosi postribolo d'ogni specie. Altra nuova non vi volgio dare hora di qua, ma se mi rispondete vene darò delle più belle.

- ↑ See Bradford: Cesare Borgia. P. 206.

- ^ Hermann-Röttgen: The Borgia family. P. 64, incorrectly dates the letter to July 16, 1502, but July 16, 1501 is correct, cf. also Eugenio Garin: Renaissance characters. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1991, pp. 50f.

- ^ Oskar Panizza: The Love Council and other writings , ed. by Hans Prescher, Luchterhand: Neuwied and Berlin, 1964, p. 144 with note 1; Giustiani is quoted there from: Charles Yriarte : Les Borgias, Vol. 2, Paris 1889, p. 40.

- ^ Otto von Corvin-Wiersbitzki: Pfaffenspiegel. Historical monuments of fanaticism in the Roman Catholic Church. 43rd edition. Berlin-Schönefeld, 1934 (Rudolstadt edition), p. 179.

- ^ Karlheinz Deschner: Kriminalgeschichte des Christianentums . Volume 8: The 15th and 16th Centuries. From the exile of the popes in Avignon to the peace of religion in Augsburg. Reinbek near Hamburg: Rowohlt 2006, ISBN 3-499-61670-X , p. 327f.

- ↑ Geiger: Alexander VI. and his court. P. 82.

- ↑ Liber notarum ed. Enrico Celani (see note 2), p. 303 with note 1.

- ^ Peter de Roo: Material for a History of Pope Alexander VI, His Relatives and His Time . Volume 5: Alexander VI and the Turks; his death and character. Bruges: Desclée, de Brouwer & Co. 1924, p. 196.

- ↑ A. Pieper: The original of the Diarium Burchardi. In: Roman quarterly for Christian antiquity and church history. 7/1893, pp. 387-403, here p. 396.

- ↑ Geiger: Alexander VI. and his court. P. 86.

- ↑ Geiger: Alexander VI. and his court. P. 82.

- ↑ Reinhardt: Alexander VI. P. 211.

- ↑ Neumahr: Cesare Borgia. P. 224.

- ↑ Reinhardt: Alexander VI. P. 210f.

- ↑ Reinhardt: Alexander VI. P. 211. Neumahr argues similarly: Cesare Borgia. P. 226.

- ↑ Volker Reinhardt: The Borgia. Story of a scary family. 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62665-4 , p. 102.

- ↑ Reinhardt: Alexander VI. P. 211.

- ↑ Reinhardt: Alexander VI. P. 213.

- ↑ Ludwig von Pastor: History of the Popes since the end of the Middle Ages. Volume 3: History of the Popes in the Renaissance Age from the election of Innocent VIII to the death of Julius II. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder 1899, p. 478 with note 2.

- ^ Bradford: Cesare Borgia. P. 206.

- ↑ Cf. Life of Benvenuto Cellini, translated by Goethe. Frankfurt am Main: Insel, 1981. There z. BS 59–63 (first book, fifth chapter): Cellini and Michelangelo take part in a banquet with courtesans; P. 133–144 (second book, first chapter): Cellini falls in love with the Sicilian courtesan Angelika in Rome and wants to bring her home.

- ↑ Neumahr: Cesare Borgia. P. 225.

- ^ Hermann-Röttgen: The Borgia family. P. 55.

- ^ Hermann-Röttgen: The Borgia family. P.56.

- ^ Hermann-Röttgen: The Borgia family. P. 59.

- ^ Hermann-Röttgen: The Borgia family. P. 56f.

- ^ Hermann-Röttgen: The Borgia family. Pp. 59-61.

- ^ Oskar Panizza: The Love Council and other writings , ed. by Hans Prescher, Luchterhand: Neuwied and Berlin, 1964, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Oskar Panizza: My defense speech in the matter of the love council before the royal district court Munich I on April 30, 1895 , in: Ders .: Das Liebeskonzil (as in the previous note), pp. 141-144 with note 1.

- ↑ Detailed information with press reviews

- ↑ Table of contents ( Memento of the original from June 13, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ The chestnut ball in radio play tips ( Memento from June 13, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Il Ballo delle Castagne at progarchives

- ↑ Summary of the episode