Oskar Panizza

Leopold Hermann Oskar Panizza (born November 12, 1853 in Kissingen , † September 28, 1921 in Bayreuth ) was a German psychiatrist , writer , satirist , reform orthographer , psychiatric critic, critic of religion and publicist .

In his writings, Oskar Panizza attacked the Wilhelminian government , the Catholic Church , sexual taboos and bourgeois morals . It has a special role in German literary history: the loner of Munich modernism can only be roughly classified between naturalism and expressionism . Panizza's writing style was spontaneous, fleeting, and unconventional - similar to later Expressionism; from 1893 he preferred to write in phonetic orthography. Although he often used the formal language of naturalism, the majority of the stories and poems are focused on the narrator's inner life, which is often very different from the real outside world. The topics were often autobiographical and mainly served the self-therapy of the mentally unstable author.

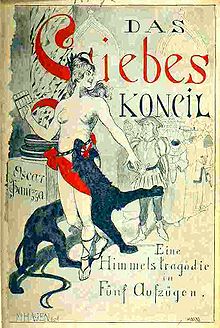

Panizza's main work is the satirical drama The Love Council , published in 1894 - an anti-Catholic grotesque unprecedented in literary history, which earned the writer a year in prison. Panizza's bizarre stories, in which he combined realism and fantasy , are also important. As an extremely polemical publicist, Panizza mainly used satirical methods and from 1897 to 1900 published the magazine Zürcher Diskußjonen , in which he represented individual anarchist and atheist beliefs. Panizza's lyrical oeuvre is primarily received as a remarkable testimony to his increasing insanity. While the first publications were still clear imitations of romantic poetry, the expressive poems of Parisjana , published in 1899, are provocations in terms of content and style, which even contemporaries who were friends of the past rated as “material for the insane doctor”.

Oskar Panizza's work, which was accompanied by spectacular literary scandals, can hardly be separated from his eventful life story: After a strictly pietistic upbringing and a school period characterized by refusal to perform, he became an assistant doctor in psychiatry , but soon turned to literature. His blasphemous provocations brought him to a sensational trial in 1895 for a year in prison for blasphemy . He gave up his German citizenship, went into exile in Zurich and, after being expelled there, to Paris . In 1899 his last work printed during his lifetime was published, the collection of poems Parisjana, dedicated to the writer Michael Georg Conrad . After its appearance, an international wanted for him was searched for lese majesty and all his assets remaining in Germany were confiscated. Returning to Germany impoverished, the former psychiatrist Panizza, who had apparently been infected with syphilis while studying, ended up in a mental hospital as a paranoid mental patient ruled by delusions and hallucinations . After 16 years in the sanatorium, he died in 1921, knowing that he had failed as a poet: “I lived in trouble”.

No other author in Wilhelmine Germany - with the possible exception of Frank Wedekind - was so affected by the censorship , and no one was persecuted by the judiciary for his literary works as harshly. Almost all of his books were banned and confiscated shortly after their publication, a performance of his plays was unthinkable for decades and his family refused to release the copyrights after his death. A reception of his works could only begin in the late 1960s, and this did not happen on a larger scale until the 1980s.

Youth and early years

Confessional conflict in the parental home

Oskar Panizza grew up as the fourth of five children (Maria, 1846–1925, Felix, 1848–1908, Karl, 1852–1916, Oskar, 1853–1921, and Ida, 1855–1922) of the hotelier Karl Panizza (born September 30, 1808 in Würzburg ; † November 26, 1855) and his mentally ill wife Mathilde, née Speeth (born November 8, 1821; † August 13, 1915). In the 17th century a branch of the Panizza family immigrated from Lake Como to Germany (the name should therefore be emphasized on the second syllable) and initially settled in Mainz. Oskar's grandfather Andrea Bonaventura Leopold (o), born on July 14, 1772 in Lierna on Lake Como, came from a family of fishermen and basket weavers, but went to Würzburg in 1794 to plant mulberry trees and raise silkworms, where he became a citizen and merchant and died on April 20, 1833 and is buried in the main cemetery. He married the wealthy Anna Schulz from Augsburg, had 14 children and died on April 20, 1833. His son Karl Panizza had worked his way up from waiter to owner of the leading hotel in Kissingen , the Russischer Hof , but also accumulated debts in the process. In 1844 he met Mathilde Speeth, who was thirteen years his junior and whom he married after a few days.

As deeply Catholic as the paternal Panizza family were, the Mathildes family were militantly Protestant . She emphasized her origins from the allegedly "aristocratic Huguenot family de Meslère", who fled France to Sonneberg / Saxony in 1685 and took the real name of Mechthold. Actually was an ancestor maternal Otto Mechtold, together with a brother in the St. Bartholomew emigrated from France and in 1583, that was one hundred years ago, died in Coburg. According to the church book entry, it was originally called "de Messler". Mathilde Panizza paid little attention to her paternal line, the Catholic family Speeth (Speth). Her father was Johann Nepomuk Speeth (1780–1834), wine merchant and merchant in Coburg, later resident in Würzburg. His brothers included the architect Peter Speeth , the Catholic theologian, canon and art writer Balthasar Spe (e) th and the Württemberg Lieutenant Colonel Valentin von Speeth, Eduard Mörike's father-in-law .

The confessional conflict shaped the early years of Oskar Panizzas: The father Karl, who had initially promised a Protestant baptism of their children after a violent disagreement in the marriage contract, insisted on their Catholic baptism and upbringing. Mathilde's mother Maria (née Mechtold), Oskar Panizza's grandmother, who had agreed with her husband Johann Nepomuk Speeth to bring up the children in the Protestant faith, experienced the same thing. After the couple moved from Coburg to Catholic Würzburg, Johann Nepomuk is said to have broken the contract and Mathilde Speeth and her siblings were baptized Catholics. Only on the death bed did the father allow her mother Maria to raise the children Protestant. Mathilde now had to convert to the Protestant faith. Oskar Panizza's mother was increasingly filled with violent religious fervor and in later years wrote pietistic edification works under the pseudonym "Siona" .

Karl died of typhus in November 1855, heavily indebted . Mathilde saw God's punishment in the early death for the broken promise to bring up the children in a Protestant manner, and now had them renamed Protestants. On the other hand, the Catholic priest Anton Gutbrod filed a lawsuit with the Kissingen district court on the grounds that Karl was not in his right mind when signing a corresponding declaration of consent two days before his death. The long and spectacular trials became known as the Bad Kissinger denominational controversy, turned into a scandal by the press and finally carried to the court of the Bavarian King Maximilian II . The courts upheld the pastor's action in every instance; Mathilde's submission to Maximilian II in 1858 was unsuccessful. Despite threatened prison sentences and fines that she did not pay, Mathilde continued her efforts privately. She withdrew her children from the Bavarian state and repeatedly sent them to various relatives in Swabia and Hanau in the Electorate of Hesse . In 1859, the king finally accepted the unenforceability of the court judgments and decided that the family's private life must be respected.

schooldays

Against all state instructions, Oskar was brought up according to strictly pietistic principles and for several years received private lessons in the semi-official school of Johann Wilhelm Schmidt. From 1863 until his confirmation in 1868, Oskar Panizza attended the boys' institute of the Pietist Brethren in Kornthal in Protestant Württemberg and then the grammar school in Schweinfurt , where he lived with a bookseller. In 1870 he switched to a high school in Munich at his own request and lived there with his uncle, the parish priest Feez. Oskar, who increasingly attracted attention by refusing to perform, was not promoted to secondary school , so that his mother's hopes that he might complete a degree in theology were soon dashed. Therefore, from 1871 he took private lessons in commercial subjects and French, but concentrated more and more on literature and music. During this time he took singing lessons at the Munich Conservatory .

Failed career attempts and the military

When Mathilde realized in 1873 that Oskar would not have great success either as a businessman or as a singer and instead enjoyed himself in the frivolous city, she brought her rebellious son back to Kissingen so that the almost 20-year-old could learn the hotel trade there and finally the " Russischen Hof ”, which Mathilde ran with far greater success than her husband had managed. Now the conflict between mother and son escalated completely and Mathilde soon saw that this plan would not be successful either.

Instead, Oskar Panizza began a traineeship at the Jewish banking house Bloch & Co. in Nuremberg , for which his brother Karl (* on February 15, 1852) also worked, but which he broke off after three months. After this new disaster, he returned to Munich and resumed his music studies at the conservatory, but was soon called up for one-year military service, which he performed from 1873 to 1874 with the 7th Company of the 2nd Bavarian Infantry Regiment in Munich. Frequent arrests and psychosomatic illnesses were an expression of the problems he had during the hard time in the Bavarian army. Towards the end of his service life, he became infected with cholera .

After his military service, Panizza initially resumed his music studies in Munich in 1874 and began to attend seminars at the university's philosophy faculty . It became clear to him that the missing school-leaving certificate would remain an insurmountable hurdle for further academic studies. So he decided to visit his old grammar school in Schweinfurt again. In 1876, now 23 years old, he successfully passed the Abitur there.

Studied medicine and worked as a psychiatrist

Following the advice of his mother and her brother-in-law Feez, Panizza enrolled at the Medical Faculty of Munich University in 1877. He completed his medical studies very successfully, became assistant to Hugo von Ziemssen , the pathologist and director of the municipal clinic on the left of the Isar , and was awarded summa cum laude in 1880 with a dissertation on myelin, pigment, epithelia and micrococci in the sputum at von Ziemssen even before the Doctorate in state examination and soon thereafter approved. Afterwards, as part of his military service, he initially worked for a few months in a military hospital and then went to Paris for six months with letters of recommendation from Ziemssens . Instead of visiting the local hospitals and psychiatric institutions as planned, however, the study of French literature and, above all, the theater cast a spell over him.

Panizza worked from March 1, 1882 to 1884 as (IV.) Second-class assistant doctor at the Upper Bavarian District Insane Asylum in Munich under Bernhard von Gudden , the doctor of Ludwig II , who later died with him in Lake Starnberg (the circumstances of the Panizza portrays death in The King and his Ship of Fools ). Due to impaired health and differences with his boss, Panizza gave up his position as a ward doctor looking after 170 out of 650 patients. After that, apart from minor medical services as a general practitioner, he was almost exclusively active in literature.

Syphilis infection

A vacation trip in the spring of 1878 took Panizza first to northern Italy and then to Naples. According to his own statements, he contracted a syphilis infection on this trip , but it is more likely that he contracted a prostitute in Munich. However, it is also possible that Panizza merely invented the disease so that it should distinguish him in a special way and arouse associations with other syphilitic artists. Even as a student he had acquired the nickname Mephisto , not without his own involvement, and liked to stylize himself as a "brilliantly crazy syphilitic person".

Panizza later stated that his walking disability was a consequence of syphilis (or neurosyphilis ), which was still incurable at the turn of the century . On the other hand, some doctors diagnosed only a chronic periostitis with callus formation instead of a gumma caused by syphilis on the right inner thigh, and Panizza's mother also attributed the disability to an accident in his childhood.

From psychiatrist to poet

Decision for the literature

A tense relationship with von Gudden, his poor health and the desire to have more time available for his literary ambitions, Panizza quit his position as a neurologist after two years and he settled down as a general practitioner for a short time. Depression followed , which lasted for about a year. At that time Oskar Panizza suffered from the fear of going mad . This fear was fueled by two suicide attempts by his sister Ida (* June 7, 1855; † December 20, 1922 in Erfurt, Catholic, then Protestant and then again Catholic) and by the death of his uncle Ferdinand Speeth, who was in a religious madness in 1884 The insane asylum of the Juliusspital Würzburg died. Another maternal uncle shot himself. Therefore, from October 1885 to October 1886, Oskar Panizza “fled” to London .

In order not to have to compromise in his literary work, he asked his mother for financial support. She had leased the hotel a short time beforehand, but was unwilling to support Oskar's literary ambitions. After a month-long argument, she finally promised him an annual pension of 6,000 marks.

Lyrical attempts

Panizza's first literary publication appeared in 1885, the volume of poems Düstre Lieder . The poems, which are clearly in the tradition of the admired Heinrich Heine , were neither a sales success nor did they provoke a public response. Nonetheless, the book was a liberation for Panizza: the writing had a therapeutic effect on the mentally unstable poet, whom literature (as a "drainage agent") had already served as a psychological relief in 1871. It helped him overcome his "moody depression" - a circumstance that led him to believe that only uninterrupted writing could keep him sane. Since that experience he has lived as a freelance writer. He became an excessive reader whose reading ranged from Martin Luther and the syphilitic Ulrich von Hutten to Ludwig Tieck , Edgar Allan Poe , Heinrich Heine and ETA Hoffmann to his contemporaries.

The London songs published in 1887, like the volume of poetry Legendäres und Fabelhaftes published in 1889, remained without criticism and ended Panizza's lyrical endeavors for the next ten years . In his oeuvre as a whole, poetry was to play a very subordinate role, even if he regarded poetry as the highest form of human expression throughout his life. Panizza's writing style was spontaneous, fleeting, and unconventional - similar to later Expressionism .

First literary success with prose stories

In 1890 Oskar Panizza made his debut as a prose author with the grotesque Twilight Pieces, inspired by Poe and combining realism and fantasy . Although he sometimes used the formal language of naturalism , a large part of his bizarre stories and poems were based on the inner workings of the narrator, which often differed greatly from the real outside world. For the most part, he took up topics and events from his own life.

In 1892 Panizza published the stories From the Diary of a Dog, dedicated to the memory of Jonathan Swift , and in 1893 switched to a phonetic notation with the Grotesque Visions . Among the ten stories in this collection is the satire Der Operirte Jud ' . The Jewish protagonist of the story can not shed his true Jewish essence even through operations, blood transfusions, changes in behavior and conversion to the Protestant faith. This narrative was interpreted as an expression of an extremely anti-Semitic , ultimately racist attitude, which was also not atypical for anarchist-oppositional German intellectuals at the turn of the century. On the other hand, the Operirten Jud 'can also be read as a parody of the tragic failure of Jewish attempts at assimilation. A few years later, Panizza described anti-Semites as "screamers hostile to culture."

Panizza had also started as an editor for the naturalistic magazine Die Gesellschaft , for Moderne Blätter and other magazines. From 1891 he also gave lectures, including the report on Genius and Wahnsinn , which was largely copied by Cesare Lombroso , but which was nevertheless critical and attracted the attention of the authorities ("Schenie und Wahnsinn", held on March 20, 1891, Central Halls of the Society for Modern Life ), an essay on Realism and Pietism (both 1891) and on Die Minnehöfe of the Middle Ages (1892). Panizza also began to play a role in the Munich bohemian scene. For a few months he was next to Michael Georg Conrad , who had introduced him to the Munich "Society for Modern Life" in 1890 , chairman of the literature association Society for modern life and board member of the theater association of the newly founded Free Stage .

Attacks on Church and State

Panizza came into conflict with the state for the first time when the Landwehr district commander asked the reserve officer in the summer of 1891 to resign from the “Society for Modern Life”, as these “realistic tendencies seek to break with the given and with the secular and the power of the Church to run the risk of conflict ”. When Panizza refused, he was dishonorably discharged from the army . Not long afterwards, the prosecution confiscated the Almanac Modern Life , for which Panizza had contributed The crime in Tavistock Square . This brought him a charge of offenses against morality, which, however, was soon dropped.

With the next three publications, Panizza's texts became increasingly biting against the state authorities and especially against the Catholic Church . The satire The Immaculate Conception of the Popes (1893), disguised as a translation from Spanish and “dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the bishop of Leo XIII”, expanded that of Pius IX. proclaimed the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary upon the procreation of the Popes. The book was judicially confiscated in Stuttgart and banned for the whole of Germany in the so-called " objective procedure ". The Holy Public Prosecutor followed in 1894 and the book Der teutsche Michel and the Roman Pope, dedicated to his (Panizzas) mother, followed . Old and new from the struggle of Teutschtum against Roman cunning and paternalism in 666 teses and quotations , which was also confiscated in 1895.

With a bit of showmanship, Panizza took over the role of a brilliantly crazy syphilitic in the radical Munich avant-garde, who did not let any opportunity for literary provocation slip by. Although he had achieved a certain fame through his publications within Munich Modernism , he had not achieved the literary breakthrough he had hoped for when he wrote the work for which he was to become notorious in 1893 at the age of forty: The Love Council .

The love council and the consequences

Major work and targeted literary provocation

Panizza's main work is the satirical "Heavenly Tragedy" The Love Council - an anti-Catholic grotesque unprecedented in literary history . The drama explains the sudden appearance of syphilis at the end of the 15th century as a divine commission of the devil to punish depraved humanity and thematizes the Catholic image of God , hypocritical piety and the decadence of the Renaissance popes .

The scenes of the action are heaven , hell and the court of the Borgia Pope Alexander VI. in the year 1495. God the Father , a senile and frail old man, the feeble and debilitating Christ and the hardened Virgin Mary receive news of scandalous conditions on earth, especially in Naples, and of orgies at the court of the Pope. For Easter they take a look at the Vatican Palace themselves and witness obscene games and intrigues of court society. Therefore they negotiate a deal with the devil : The devil is supposed to invent a terrible punishment, which should immediately follow carnal sin , but which should leave the souls of men capable of redemption , since God's creative power has been used up and he can no longer create new people - he is therefore dependent on the existing ones. In return, the devil demands a splendid portal for the run-down hell, the right to unannounced consultation hours with God and above all the freedom to spread one's thoughts, because “if someone thinks and is no longer allowed to communicate his thoughts to others, that is the most hideous of all tortures. ”The punishment devised by the devil is now the“ lust epidemic ”syphilis. In order to bring this to earth, the devil begets with Salome , the most sly figure in hell, the "woman", an irresistibly beautiful woman who first the Pope, then the cardinals, the bishops and finally the rest of the church hierarchy with the disease infected, which is rapidly spreading throughout humanity.

The main influences for the love council were the play Germania, published in 1800 under the pseudonym Pater Elias , a tragedy with similar motifs. Other extensive models, named by Panizza himself, are Goethe's Faust , La Guerre des Dieux ancien et modern from Évariste de Forges de Parny , Sebastian Sailer's case of Lucifer from the second half of the 18th century and the Jesuit dramas with their heaven and hell scenes and the allegorical ones Representations of virtues and vices . The love council is dedicated to the memory of Ulrich von Hutten , who suffered from syphilis and died from it after a long suffering.

The Panizza case

Anti-Catholic satire became the biggest literary scandal of the 1890s. In October 1894 the love council appeared at Jakob Schabelitz's in Zurich. Panizza sent review copies to journalists and friends so that the book became a much-discussed literary topic before it even hit the German market. Theodor Fontane , Detlev von Liliencron , Otto Julius Bierbaum and others reacted enthusiastically to the spectacular work.

The love council was only available in bookstores for a few weeks: after a discussion in the Allgemeine Zeitung , the police confiscated all copies accessible in Germany on January 8, 1895, and the Munich public prosecutor's office under Baron von Sartor brought charges of blasphemy based on Section 166 of the Reich Criminal Code . One problem was proving that the work printed in Switzerland had even found readers in Germany. Finally, two Munich booksellers declared that they had sold 23 copies and a police officer from Leipzig made a declaration that they had read the book and had "taken offense" at its contents - he signed his advertisement with "i. A. Müller ".

The case went through the German press. Panizza found advocates among liberal and social democratic journalists, but intense hostility in conservative newspapers. Even Thomas Mann , who Panizza during his studies in Munich in the "dramatic Academic Club" had met personally expressed understanding for tracking the blasphemous "bad taste" by the judiciary. His criticism was based on Panizza's published defense speech and, like many other critics, had probably not read the book himself.

Since conservative politicians suspected a political opposition, as it actually only developed around 15 years later, the Panizza case turned into a highly political trial against “ modernity ”. The public prosecutor therefore proceeded against Panizza with extraordinary severity. In the trial that took place on April 30, 1895 before the District Court of Munich I , Panizza took on the role of a champion for the freedom of modern literature and stylized himself as a martyr, consciously accepting the risks of such an attitude. Against the advice of his friends, who had previously advised him to flee abroad in vain, he fought against the state in his literary and art-historical defense. Defiantly, he also refused to deny that he had intended to publish the book published in Switzerland for Germany - probably the only chance of an acquittal.

With his speech on the basic values of artistic freedom , he was hardly able to convince the twelve jury , to whose draw the judiciary had invited 28 citizens with consistently low levels of education. Panizza's confession “I declare that I am an atheist ” had provoked a condemnation. One of the jurors said quite frankly: "When the dog would have been tried in Lower Bavaria, it didn't come alive!" Even the friend and sponsor Michael Georg Conrad , who was invited by Panizza as an expert , stood in a state of disbelief in the face of this behavior and had doubts about the Panizzas hardly hide mental health. So the trial inevitably resulted in a condemnation of Panizzas. No other writer in the Wilhelmine Empire was punished with comparable severity: unlike Frank Wedekind or Hanns von Gumppenberg , Panizza was not only sentenced to brief imprisonment , but to a whole year of solitary confinement and he also had to pay the costs of the proceedings and his stay in prison.

Between trial and imprisonment

Panizza was arrested in the courtroom and only released after three weeks' imprisonment on an exceptionally high bail of 80,000 marks until the final decision of the Imperial Court in Leipzig.

Five months before the love council was published , Panizza had formulated in an essay on “People's Psychology” that “a prison sentence for a cause that was defended in good faith is almost a guarantee of popularity among the masses”. In this short period of time he consistently tried to benefit from the public's attention and in July published the text My Defense in the matter of the “Love Council”. In addition to the expert report by Dr. MG Conrad and the judgment of the k. District Court of Munich I. The later eminent philosopher Theodor Lessing had also been an assistant doctor in Munich, took up the debate and wrote a dedicated defense two months after the trial, and, as he then said in his own defense, “without the condemned piece at all to know. ”The effort for Panizza resulted in a search of Lessing's apartment and the confiscation of some of his poems by the police.

At the premiere of Georg Büchner's comedy Leonce and Lena in an open-air performance by the Munich theater association “Intimes Theater” on May 31, 1895, directed by Ernst von Wolhaben , Oskar Panizza played the court preacher - almost 60 years after the play was written. On the evening before his trial, Panizza had participated in the first performance of the Intimate Theater in August Strindberg's "Believer". On October 11, 1895 - when Oskar Panizza had already been in prison for two months - the premiere of his one-act play A Good Guy took place in Leipzig . The play about an inheritance dispute is the only work by Panizza that can be described as naturalistic and remained the only play staged during his lifetime.

Illusionism and the salvation of personality

Panizza's only philosophical publication fell in the period between trial and imprisonment in 1895: Illusionism and the Salvation of Personality. Sketch of a worldview. In it, Oskar Panizza adapted the philosophy of Johann Caspar Schmidt (whose pseudonym Max Stirner dedicated his sketch to Panizza as a souvenir), whose work The Only One and His Property was the model for Panizza, and vehemently criticized a one-sided scientific view of the human psyche. This was a clear criticism of the anatomical- neurophysiological psychiatry, as advocated by Gudden.

In his world-denying "illusionism", which derives man as a puppet and machine, Panizza formulates the conviction that there are no spiritual norms and that only the radical deeds and ideas of individuals guide world history. For Panizza, free will was a “form of illusionism”. For the individual, the outside world only exists as a projection in his head, whereas hallucinations are real for him regardless of the real world. This conviction is a clear reaction to Panizza's latent mental disturbance, which would later break out and which the experienced neurologist diagnosed as such. The gap between the real outside world and inner world experience is one of the narrative leitmotifs in Panizza's work. Even the love council did not focus on God, but on the Catholics' image of God - a difference that Panizza's judges and the jury could not understand. Probably the strongest theme of the strongly autobiographical story The Yellow Kroete, written in 1894 and published as a special edition in 1896, is the discrepancy between the objective and the subjectively perceived world.

One year in prison

On August 8, 1895, Panizza entered the one-year solitary confinement in Amberg Prison, which he served in full. A pardon, which Panizza's attorney Georg Kugelmann justified on August 30th to the Prince Regent with a mental illness and the insanity of his client, was unsuccessful, but ten years later it contributed not insignificantly to Panizza's incapacitation. The application was submitted without Oskar Panizza's knowledge - probably at the instigation of the family.

Panizza was allowed to write while in custody. However, since he was not allowed to publish, Panizza published some articles and reviews from the prison in the magazine Die Gesellschaft under a pseudonym, such as a review of Wedekind's Der Erdgeist or the psychiatric-critical article News from the cauldron of madness fanatics published in 1896 . Further writings written in Amberg appeared after his release from prison.

The manuscript A year in prison - my diary from Amberg , which Panizza sent to Conrad, dismissed Conrad as literarily worthless and it remained unprinted. The prisoner's diary, which has only survived in fragments, gives an impression of the psychological torments of the prison period. Among the simple and coarse prisoners and guards, the prison chaplain Friedrich Lippert, who later became Panizza's guardian, was his only interlocutor. One consequence of the humiliation in prison was a clear politicization of Panizzas, who saw the mental and physical humiliation by guards and prisoners as a systematic part of the state penal system.

Farewell to Munich

When he returned to Munich in August 1896, most of his friends were shocked by the profound changes that the imprisonment had caused in Panizza's character. He looked emaciated and pale, had become a solitary skeptic.

While in prison, Panizza had written the pamphlet Dialoge im Geiste Hutten (best known probably the Ueber die Deutschen ), which contained five dialogues, and the pamphlet Abschied von München , with which he programmatically turned away from Germany and announced his emigration to Switzerland. A good month after his release from prison, Panizza applied for his Bavarian citizenship to be released and moved to Zurich in October 1896. Before that, he brought even more literary projects to an end, including the last article for society , The Classicism and the Penetration of the Variété , in which he advocated a renewal of dramatic art from the spirit of the variety show , and the “Into the Shore”. Advised elaboration of an earlier article on the medieval Haberfeldttrieb in book form, which was published by the renowned S. Fischer Verlag .

Emigration to Switzerland

Zurich Discussions

Although Oskar Panizza had turned his back on Munich and Germany of his own volition, he saw himself as an exile , an outcast and placed himself in the tradition of political refugees like Heinrich Heine .

Since Panizza found no publisher and no magazine that wanted to publish his new books or his articles, he founded in Zurich its own publishing house Zurich discussions and gave it in May 1897, the Zurich Diskußjonen out that the subtitle leaflets from the whole area of modern life carried. Basic questions about the relationship between the individual and the state, between idea and action determined the editorial orientation of the magazine. In addition to literature and art, topics included religious, erotic, moral history and political essays, satires and short stories. Among the articles so unusual title, see how The pig poetically, mitologischer and immoral historical relationship or in Jesus Christ a paranoia Noting Christ in psicho-patologischer lighting .

Allegedly, the publications were based on conversations on discussion evenings. Whether these actually took place and how many guests took part can no longer be determined today. What is certain is that Panizza wrote most of the contributions himself under his own name and the pseudonyms Louis Andrée, Hans Dettmar, Sven Heidenstamm, Hans Kistenmaecker, Jules Saint-Froid (so in Die Gesellschaft ) Sarcasticus and with the symbol ***. A few names of other authors are known, however, such as Fanny Countess zu Reventlow , Léon Bazalgette , Ludwig Scharf , Heinrich Pudor and the Russian immigrant Ria Schmujlow-Claaßen , with whom Panizza had a long-standing friendship, wrote for the Zurich Discussjonen .

The magazine had a maximum circulation of 400 copies and was supported by the German patron Otto von Grote (* 1866), the son of the politician Otto Adolf Freiherr von Grote . When Panizza, who had entered Switzerland with only 600 marks in credit, ran into financial difficulties personally and as a publisher, Grote demanded editorial influence. Panizza refused, however, and preferred to reduce the number of copies of the Zurich Discussions .

Psichopatia criminalis

In addition to the magazine, a satire was created in Zurich on the political exploitation of psychiatry: The Psichopatia criminalis with the subtitle Instructions to psychiatricly identify and scientifically determine the mental illnesses recognized by the court as necessary. For doctors, laypeople, lawyers, guardians, administrative officials, ministers, etc. In the style of a scientific study, the title and structure of which is based on Psychopathia sexualis (Krafft-Ebing) , the former psychiatrist explains how, using the example of the March Revolution one could have nipped the criminal movement through a "moderately large madhouse between Neckar and Rhine, about the size of the Palatinate [...], I wanted to say: the epidemic psichosis" and what lessons can be learned from it for the present. Panizza treats Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus , Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart , Wilhelm Weitling , Robert Blum and Max Stirner as exemplary cases from history . The Psichopatia criminalis is clearly shaped by the anarchist and anti-monarchist attitudes that Panizza developed during imprisonment in Amberg and that had intensified in the Zurich exile. The content of the brochure, published in 1898, is related to the lecture Genius and Madness given in March 1891 and the treatise The Illusionism and The Salvation of Personality from 1895.

Expulsion from Switzerland

Panizza's mood in Switzerland fluctuated between depression and great lust for life and fighting. Although he became the focus of a group of intellectual, sometimes anarchist “revolutionaries”, he did not, or only apparently, tie in with his old bohemian life in Zurich . He hardly had any close friendships and became increasingly isolated. He spent hours reading to his beloved dog Puzzi, whose death in 1897 shook him deeply. Nevertheless, he felt comfortable in his host country and applied for Swiss citizenship . In this situation, he was completely unexpectedly expelled from Zurich (and thus from all of Switzerland) on October 27, 1898, after seeing the 15-year-old prostitute Olga Rumpf in his apartment once or twice a week from December 1897 to spring 1898 and allegedly photographed them naked for medical purposes. No prosecution took place; In Switzerland, sexual intercourse with girls under the age of 15 was also a criminal offense. The actual cause of the expulsion, however, is likely to have been a political reaction to the assassination attempt on the Austrian Empress Elisabeth on September 10, 1898 in Geneva, as a result of which the Swiss authorities systematically cracked down on anarchists, socialists and intellectuals who were in contact with these circles . Panizza left Zurich on November 15, 1898 and arrived six days later in Paris with his library of 10,000 books, a buffet and a bed.

Exile in Paris

Depression, hallucinations, and paranoia

The recent emigration, which had hit Panizza like a blow, led him into a serious psychological crisis. He was in Paris increasingly resignation, depressive episodes, hallucinations and paranoia ruled and moved largely from human society back. The fear of being deported again was so great that he even refrained from unpacking his library from the moving boxes in his spacious apartment on Montmartre for years.

Panizza became more bizarre and shy of people than ever. Only a few earlier acquaintances such as Frank Wedekind , Anna Croissant-Rust , Gertraud Rostosky and Max Dauthendey visited him occasionally. In his former friend, the lyric poet Ludwig Scharf , he even wanted to recognize a secret police officer of the Berlin government and threw him out of his apartment without further ado. As much as Panizza's delusional system of being the subject of a far-reaching conspiracy, the initiator of which was Kaiser Wilhelm II , was marked by delusions of persecution and megalomania , the suspicion of being monitored by the police does not seem to have been completely unfounded: Post from him arrived at his mother's place open and from the other side threatened his former patron Otto von Grote for fear that both previous correspondence (Grote had sent letters with pornographic content to Panizza) could have unpleasant consequences for him, with his connections to the German embassy and via this to the Paris Aliens Police. Von Grote remarked in a letter to Michael Georg Conrad: "Such insane people are unpredictable!"

Parisjana and wanted wanted report

The six years that Panizza spent in Paris (5-room apartment on Rue des Abbesses XIII ) were not nearly as productive as the time in Munich and Zurich. Until 1901 he continued to publish the Zurich Discus Zjonen and kept the title in Paris. Panizza now openly confessed to anarchism as the “Principle of Negazjon” and increasingly saw himself in a personal battle with Kaiser Wilhelm II , whom he not only held responsible for his expulsion from Zurich, but who also wanted to expel him from Paris (In Laokoon or Panizza expresses his hatred of Wilhelm II beyond the limits of the mezzanine .)

Panizza's last book publication, the volume of poetry Parisjana (1899), therefore became a personal challenge to the German Emperor, a pamphlet with a sharpness that Panizza had not achieved before. In the artistically less ambitious, but all the more time-critical ballads in Panizza's typical phonetic spelling, he denounced the hated Wilhelmine Germany as an intolerable class state in which the people and art were oppressed, and called on the subjects to "revolution".

In a strange misunderstanding of the meanwhile nationalistic convictions of his former friend Michael Georg Conrad, he dedicated the Parisjana to him . Outraged, Conrad turned to the publisher of the society , Ludwig Jacobowski : “It doesn't help, Panizza has to be tidied up cleanly and as quickly as possible”, the collection of poems was “Material for the mad doctor”, Panizza “in the educated world a dead man ". Conrad, who saw "the whole German people being pelted with feces" in Parisjana , published violent reviews in society , in Das litterarien Echo and in Die Wage . As a result, the public prosecutor's office became aware of the Parisjana , on January 29, 1900 Baron von Sartor again brought charges and a day later a confiscation order was issued. Since February 2nd, Panizza has been searched for with an international profile .

On February 28, 1900, the public prosecutor applied for the confiscation of Panizza's property because of the risk of flight. Since the latter was stateless and was staying abroad, the proceedings were soon discontinued, but Panizza's property in the amount of 185,000 marks remained confiscated. Now it turned out to be fatal that Oskar Panizza had accepted his family's refusal to pay him his share of the inheritance when he left for Switzerland. Support from his family, who believed they had lost their social reputation through him, was out of the question and he could not bring himself to sell his library - Panizza quickly became impoverished and soon could no longer pay the rent.

Madness, incapacitation and end in the mental hospital

Detention and declaration of insanity

In this situation he presented himself to the Munich judiciary as "Pazjent" on April 13, 1901. He was immediately arrested and interrogated at the Munich Fronfeste am Anger. On April 15, 1901, the proceedings for lese majesty were resumed, but Panizza's assets were released.

Since, based on his literary works since the love council , there were doubts about the mental health of Panizza, he was admitted for examination to the county insane asylum where he himself had worked as an assistant doctor under Gudden in the early 1880s. After the Fronfeste he found this institution almost like paradise. Here he was examined, assigned from June 22nd, until he was sent back to prison on August 3rd, 1901. When the psychiatric report was available three weeks later, Panizza was judged to be insane and paranoid , and charges against him were dropped. He was released that same evening and returned to Paris on August 28, 1901.

Expanding delusional system

After his return in November 1901, Panizza published only a few numbers of the Zurich Discussions . Although he continued to write, he couldn't even find a printer for his works. His prose collection Imperjalja , the content of which was linked to the Parisjana , therefore remained unprinted . The 1903 in the Rue des Abbesses XIII. The Imperjalja texts written in Paris form Panizza's last and most extensive work. They illustrate Panizza's conspiracy theory : According to this, a side government of Bismarck was waging a secret battle against Wilhelm II, and Panizza was the object and decisive figure of this struggle, the criticism of which the Kaiser feared more than anything else. Even behind “ Jack the Ripper ” and countless other scandals is actually the emperor, but only a few initiates like Panizza know about it. Soon there was nothing left that was not part of the great conspiracy.

Panizza isolated himself more and more from his environment, suffered from attacks of nausea and was plagued by acoustic, visual and olfactory hallucinations , which he integrated into his delusional system: he called an "air singing" for him by the whistling of imperial agents, gastritic pain led to poisoning return. Everyday objects seemed to him to articulate words, even the flight of swallows seemed to be an act directed against him. In 1903/04 the former neurologist diagnosed himself with a "dissociation of personality".

Internment, incapacitation and death

On June 23, 1904, Panizza left Paris, stayed for a few days by Lake Geneva and asked to be admitted to the Munich district insane asylum. However, this was rejected, officially because of overcrowding, in fact probably because the funding of the stateless person's therapy seemed unsecured to the director of the institution, Vocke. Panizza then turned to the private sanatorium in Neufriedenheim , from which he was expelled after ten days because of a violent dispute with the director of the institution, Ernst Rehm . Oskar Panizza rented a room in Schwabing and continued to feel harassed and mocked by people and nature. There were repeated quarrels with Munich citizens, which resulted in reports, interrogations and police surveillance.

On October 19, 1904, at the last moment, Panizza refrained from planned suicide, which he had considered several times. When he then walked from his apartment on Feilitzschstrasse stripped down to his shirt through the city to Leopoldstrasse, gave the police who had been called a false name and claimed to be a patient in the mental hospital, he was admitted to have his mental health examined. In an autobiography that Panizza wrote in the insane ward of the municipal hospital 1 / I at the request of the doctor in November 1904, Panizza proudly claimed that he had deliberately and ultimately successfully provoked this admission. The former psychiatrist Panizza writes in these notes about the patient Panizza in the third person and names the whistling as a hallucination, but at the same time as reality.

On March 28, 1905, he was transferred to the institution for the mentally ill in St. Gilgenberg in Eckersdorf near Bayreuth and in April, against his will and at the urging of his mother, he was finally incapacitated . Gudden, a son of Bernhard von Gudden and a Herrr Ungemach, who had already made an expert assessment for the Panizza district mental institution in Munich in 1901, and on whose expert opinion at the time Gudden largely based himself in 1905, were active as appraisers for the Munich district court. Oskar Panizza's guardians were Judicial Councilor Popp and his brother Felix (born March 18, 1848), after his death on March 6, 1908, Dean Friedrich Lippert, Panizza's interlocutor from the Amberg prison time. In 1907 Oskar Panizza moved to the luxury sanatorium Mainschloß Herzoghöhe in Bayreuth , built in 1894 by the Jewish doctor Albert Würzburger, where he was the only mentally ill person. Little is known about Panizza's time in the sanatorium, which he called the madhouse (he also called "Das Rothe Haus" - a poem published in Duestre Lieder ), but a letter from his mother shows that he was in 1905 wanted to take life. In Bayreuth, Panizza continued to translate Latin texts for a while and wrote the last, never completed book, The Birth of God, a mitological cycle in the sense of the course of the sun and moon . One of his last poems from 1904 bears the resigned title: "A poet who lived in trouble". After more than 16 years in the sanatorium, Oskar Panizza succumbed to repeated strokes on September 28, 1921. He was buried in the Bayreuth city cemetery on September 30, only in the presence of the prison staff. The family refused to put a tombstone for him and appear to have destroyed a large part of the unpublished estate.

reception

Contemporary reception and early legend formation

Most of Panizza's books were banned and confiscated shortly after their publication, an actual theatrical performance of his love council was out of the question for a long time and Panizza's family refused to release the copyrights for new editions of the incapacitated man - for decades, his works were hardly really received possible. The scandalous figure Oskar Panizza, however, was one of the most dazzling figures of the Schwabing bohemian scene and later a mystified figure in several literary works: Hanns von Gumppenberg describes him in his key novel The Fifth Prophet as a Mephistophelian eccentric, Oscar AH Schmitz as an alchemist, magician and demon of the world (Panizza himself saw himself as a "demon bearer" who had not been able to manifest his demon in the world). Whether Thomas Mann sketched it in Doctor Faustus cannot be proven, but it is possible. For Sigmund Freud , the Love Council was “a strongly revolutionary stage play” and Walter Benjamin valued Panizza as a “heretical painter of saints”.

In 1913 an edition of the Council of Love for the “Society of Munich Bibliophiles”, limited to 50 copies and printed in the Netherlands, was published and illustrated by Alfred Kubin . Due to strict censorship, each copy of this private edition had to bear the printed name of the future owner on the front page. The members of the society included Franz Blei , Karl Wolfskehl , Erich Mühsam and Will Vesper . A large-format oil painting by George Grosz (dedicated to Oskar Panizza) was made in 1917/18 and now hangs in the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart .

After the First World War, the "Panizza case" lived on in judicial, psychiatric and literary circles. Emil Kraepelin , who had examined Panizza, dealt with his case in his psychiatric textbooks. In the 1920s, bibliophiles paid top prices for copies of the confiscated first edition of the Love Council . Kurt Tucholsky wrote about Panizza in 1920 that “when he was still sane, he was the cheekiest, boldest, most ingenious and revolutionary prophet in his country. One against whom Heine can be called a dull lemonade and one who has come to an end in his fight against church and state (...). "

Friedrich Lippert, Panizza's guardian who retired in October 1915, published the biography In memoriam Oskar Panizza in private print together with Horst Stobbe in 1926 . Printed together with the fact in 1904 at the insistence of doctors in district mental drafted, signed on 17 November autobiography Panizza and autobiographies of Walter Mehring and Max Halbe were those memories for a long time the basis for any account of the life of Oskar Panizza. However, all of these works are inaccurate or tendentious for various reasons. The fact that Panizza was admitted to the madhouse in spite of his mental health is primarily due to Mehring, Halbe and statements by Wedekind and was soon considered a generally recognized fact. Both the role of the “authorities” and that of his family were the subject of speculation. Only since the 1980s has the view of Oskar Panizza been broadened through a more thorough study of the sources. The unprinted, extremely religiously tinged, unpublished biography of mother Mathilde takes a completely different perspective on the black sheep of the Panizza family.

Assumption by the National Socialists

One topic was Panizza's trial exclusively for left-wing intellectuals, until the end of 1927 the “Munich Observer”, a supplement to the Völkischer Beobachter , published a National Socialist interpretation of Panizza's love council and printed his story Der Operirte Jud .

Panizza's work was appropriated by the National Socialists during the Third Reich, but reduced to the appropriately usable texts. Emil Ferdinand Tuchmann , the Jewish chairman of a “Panizza Society” founded in 1928, had to go into exile in Paris in 1933. Two years later, the National Socialist cultural functionary and author Kurt Eggers published two anthologies with selected works by Panizza. In Eggers' interpretation, the individual anarchist and francophile bohemian Panizza became an anti-Semitic, anti-French and anti-British will-man. A typical result of this reinterpretation was the falsification of the book title Der teutsche Michel and the Roman Pope in German theses against the Pope and his dark men . With this title the book was published in 1940 in large numbers. A reprint appeared in the Völkischer Beobachter . Panizza had thus posthumously become a National Socialist author, whose work was personally promoted by Reichsleiter Martin Bormann .

Rediscovery in the 1960s

After the Second World War, Panizza's works were neither published nor performed for a long time and were not a topic of German studies. When Jes Petersen reissued the first edition of the Love Council as a facsimile in a small edition of 400 copies in 1962, the book was put on the index and Petersen was imprisoned. His home was searched, books and pictures were confiscated, and he was tried for distributing pornographic material. However, after violent protests from the press, all charges against Petersen were dropped. It was not until 1964 that Hans Prescher published the Love Council together with other writings at Luchterhand in larger editions. This created the basis for a broader reception of Panizzas in the German-speaking area for the first time. A French translation had already appeared in 1960, followed by a Dutch edition in 1964, an Italian edition in 1969 and an English edition in 1971.

First, in December 1965, a Munich student theater, the studio stage of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU), performed Panizza's play as a staged reading and was in conflict with the conservative AStA chairman at the LMU Munich, who later became Bavarian Finance Minister Kurt Faltlhauser , devices. The first performance of the Love Council as a play took place in 1967, 74 years after its first publication, on the Vienna small stage "Experiment" and in 1969 it was brought to a large stage at the Théâtre de Paris under the direction of Jorge Lavelli . When the love council finally had its German premiere in 1973 at the Ernst-Deutsch-Theater in Hamburg , the leading trade journal Theater heute dedicated the title report to Panizza. The expected outraged public reaction failed to materialize.

In the 1970s, only individual texts by Panizza were published in anthologies until the Love Council was published by S. Fischer Verlag in 1976 . 1977 followed from the diary of a dog , 1978 the criminal psychosis, called Psichopatia criminalis and 1979 dialogues in the spirit of Hutten with a foreword Panizza or the unity of Germany by Heiner Müller .

Film adaptation and Panizza renaissance in the 1980s

A production at the Teatro Belli in Rome under the direction of Antonio Salines in 1981 caused a veritable scandal . The Italian production Il concilio d'amore was integrated into the film Liebeskonzil by German director Werner Schroeter , which premiered in the sold-out Zoo Palast at the 1982 Berlinale . The plot of the film is not completely identical to Panizza's play; like the Italian production, it lacks the most unbridled scene at the court of Alexander VI. in the Vatican. The scenes, on the other hand, are framed by the trial of Panizza, of which they are “pieces of evidence”. The film could not meet the high expectations: Instead of the expected provocation, the film aroused rather disappointed boredom and was soon considered a flop, the criticism of religion as a harmless anachronism from the Wilhelmine era. The low-budget production was also unsuccessful financially and only attracted a small number of viewers to the few cinemas in which the film was shown.

Since then, the love council has been staged regularly, but not often. Among other things, it was performed at the Berlin Schillertheater in 1988/89, directed by Franz Marijnen and with music by Konstantin Wecker . Most editions of the works and most of the literary studies of Panizza's work and life were published in the second half of the 1980s.

Litigation in the 1990s

In May 1985, the Tyrolean provincial government banned the film as a complete surprise because it insulted the Christian religion: when the Otto Preminger Institute for Audiovisual Media Design (OPI) wanted to show the love council for six evenings in their cinema in Innsbruck, the Catholic one reimbursed Diocese complaint against the director of the OPI, Dietmar Zingl, and found the support of the public prosecutor. Despite harsh reactions of the Austrian press, the film as a short time before was the specter of Herbert Achternbusch in Tirol prohibited. In 1994 the European Court of Human Rights upheld this decision.

In Switzerland, a group called “Christians for Truth” filed a complaint against a staging of the love council by the senior class of the Bern Drama School in 1997, citing Section 261 of the Criminal Code ( disruption of freedom of religion and worship ) . This lawsuit was dismissed in 1998 by a court in Bern.

Literary studies

Until the early 1980s, scientific texts on Panizza were largely limited to the afterwords of the few editions and very isolated articles, some of which were related to the anti- psychiatry movement. After an American dissertation by Peter DG Brown from 1971 (Doghouse, Jailhouse, Madhouse) and the doctoral thesis by Michael Bauer ( Oskar Panizza. A literary portrait ) in 1983, Peter DG Brown's monograph Oskar Panizza followed in the same year . His Life and Works and in 1984 the book edition of Bauer's dissertation at Carl Hanser Verlag. After Rolf Düsterberg published a study on the Zurich Discussions in 1988 and Knut Boeser published a source documentation on Panizza's life and work in 1989, a less literary than programmatic book by Rainer Strzolka (Oskar Panizza. Stranger in a Christian Society) followed in 1993 and one in 1999 Monograph by Jürgen Müller (Der Pazjent als Psychiatrist) , who was particularly interested in the psychiatric aspects of the interpretation of the work and Panizza's biography.

To date, little has changed about the fact that most literary stories deal with Panizza, if at all, in a few sentences or only passively. Even many extensive standard works on 19th century literature or author's encyclopedias still ignore Panizza. Wherever Panizza's work is mentioned, it is today given an important special role in German literature at the turn of the century beyond naturalism .

A Panizza work edition, estimated at ten volumes, has been published since 2019, edited by the Kleist and Kafka editors Peter Staengle and the former director of the Kleist archive Sembdner and publisher Günther Emig . As of April 2019, the volumes Dämmrungsstücke (Volume 2 of the work edition) and Die Haberfeldtreiben im Bavarian Mountains were published. A moral history study. (Volume 8 of the work edition). The author's biography Oskar Panizza - Exil im Wahn by Michael Bauer , published in 2019, contains previously unpublished drawings and photos by the author . It was published parallel to his reading book "A little prison and a little madhouse" , which he edited with Christine Gerstacker and which, in addition to all the prison diaries that have survived, also contains unpublished photos and drawings by Oskar Panizza.

Commemoration 2021

On the occasion of Panizza's 100th anniversary of death in September 2021, the PEN Center Germany recalled that “no other author in the German Empire had ever been so severely punished for a publication” as Panizza did for The Love Council , and stated that “the politically motivated process is still reminiscent today because the freedom of art and freedom of expression is a fundamental right, "which" applies to protecting and defending it in the present as well ".

Works (selection)

- Via myelin, pigment, epithelia and micrococci in the sputum. Inaugural dissertation to obtain the doctorate from the medical faculty in Munich. Leipzig 1881.

- Gloomy songs. Unflad, Leipzig 1886. (Actually published in 1885).

- London songs. Unflad, Leipzig 1887.

- Legendary and fabulous. Poems. Unflad, Leipzig 1889.

-

Insulation pieces. Four stories. Friedrich, Leipzig 1890.

- (In it the stories The Wax Figure Cabinet , A Moon Story , The Station Mountain and The Human Factory )

- Genius and madness. Lecture given in the “Society for Modern Life”, Central Halls, on March 20, 1891. Poeßl, Munich 1891 (= Munich pamphlets. 1st series, No. 5 and 6).

-

From a dog's diary. Leipzig 1892.

- New edition: From a dog's diary. With an opening credits for readers by Martin Langbein and with drawings by Reinhold Hoberg. Munich 1977.

- Prostitution. A present study. In: Society. Volume 8, 3rd quarter 1892.

- Brother Martin OSB [= Oskar Panizza], The Immaculate Conception of the Popes. Translated from the Spanish by Oskar Panizza. Schabelitz, Zurich 1893.

- The Monita secreta of the Jesuits. In: Society. Volume 9, 3rd quarter 1893.

-

Visions. Sketches and stories. Friedrich, Leipzig 1893.

- (In it the stories Die Kirche von Zinsblech , Das Wirtshaus zur Dreifaltigkeit , A Criminal Sex , The Operated Jew , The Golden Rain , A Scandalous Case , The Corset Fritz , Indian Thoughts , A Negro Story and A Chapter from Pastoral Medicine )

- The pilgrimage to Andechs. First published in The Viewer: a monthly for art, literature and criticism. Hamburg, Publishing House of the Spectators, 2nd year (1894), No. 23 (from December 1, 1894); No. 25 (from December 15, 1894) payer.de

- The holy prosecutor. A moral comedy in five scenes (based on a given idea). Friedrich, Leipzig 1894.

-

The love council. A heavenly tragedy in five acts. Schabelitz, Zurich 1895. (Actually published in 1894)

- also in: Hans Prescher (ed.): The love council and other writings. Neuwied / Berlin 1964. (First edition in a larger edition)

- The German Michel and THE ROMAN POPE. Old and new from the struggle of Teutschtum against Roman-Wälsche outwitting and paternalism in 666 teses and quotations. With an accompanying word by Michael Georg Conrad. Wilhelm Friedrich, Leipzig 1894.

- Illusionism and the salvation of personality. Sketch of a worldview. Friedrich, Leipzig 1895.

- My defense in the matter of "The Love Council". In addition to the expert report by Dr. MG Conrad and the judgment of the k. District Court Munich I. Schabelitz, Zurich 1895.

- Bayreuth and homosexuality. One consideration. In: Society. Volume 11, 1st quarter 1895.

- The human brain. In: The Scourge. Volume 1, (Supplement to No. 17 of May 25) 1895.

- The yellow toad. OO (special print, 1896).

- Good guy. Tragic scene in 1 act. Höher, Munich 1896 (= Messthaler's collection of modern dramas. Volume 2).

- Farewell to Munich. A handshake. Schabelitz, Zurich 1897 (written during imprisonment in Amberg).

-

Dialogues in the spirit of Hutten. About the Germans. About the invisible. About the city of Munich. About the Trinity. A love dialogue. In: Zurich Discussions. Zurich 1897.

- New edition: Dialogues in the spirit of Hutten. With a foreword Panizza or the unity of Germany by Heiner Müller, Panizzajana by Bernd Mattheus and contributions in the spirit of Panizzas by Karl Günther Hufnagel and Peter Erlach. Munich 1979.

- The Haberfeldtreib in the Bavarian mountains. A moral history study. Fischer, Berlin 1897.

- Christ in psicho-patological lighting. In: Zurich Discussions. Volume 1, No. 5, 1897/1898, pp. 1-8.

- The sexual strain on the psyche as a source of artistic inspiration. In: Wiener Rundschau. Volume 1, No. 9, 1897.

- Nero. Tragedy in five acts. In: Zurich Discussions. Zurich 1898.

-

Psichopatia criminalis. Instructions to psychiatric elucidate and scientifically determine the mental illnesses recognized by the court as necessary. For doctors, laypeople, lawyers, guardians, administrative officials, ministers, etc. In: Zürcher Discussions. Zurich 1898.

- New edition: The criminal psychosis called Psichopatia criminalis. Auxiliary book for doctors, laypeople, lawyers, guardians, administrative officials, ministers, etc. for diagnosing political brain disease. With forewords by Bernd Mattheus and with contributions by Oswald Wiener and Gerd Bergfleth. Munich 1978; 2nd, unchanged edition, Munich 1985.

- Parisjana. German verses from Paris. In: Zurich Discussions. Zurich 1899. (Actually published in Paris).

- Tristan and Isolde in Paris. In: Zurich Discussions. 25/26, 1900.

- Visions of twilight. With introduction Who is Oskar Panizza? by Hannes Ruch and 16 pictures by P. Haase . Munich / Leipzig 1914.

- Notebooks and diaries. Except for the diary No. 67 in the manuscript department of the Munich City Library (shelf marks L 1109 to L 1110) -

Posthumously published manuscripts

- Laocoon or beyond the borders of the mezzanine. A snake study. (Probably intended for Zurich discussions. Leaflets from all areas of modern life. Special edition). With an afterword by Wilhelm Lukas Kristl . Laokoon, Munich 1966.

- News from the cauldron of crazy fanatics. Edited by Michael Bauer. Neuwied 1986.

- Imperjalja. Manuscript Germ. Qu. 1838 of the manuscript department of the State Museums of Prussian Cultural Heritage in Berlin. Edited in text transcription and annotated by Jürgen Müller. Pressler, Hürtgenwald 1993 (= writings on psychopathology, art and literature. Volume 5), ISBN 3-87646-077-8

- The Rothe House. A reader on religion, sex and delusion. Edited by Michael Bauer. Allitera / edition monacensia, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-86520-022-2 .

- Autobiography. [1904] In: Friedrich Lippert: In memoriam Oskar Panizza. Edited by Friedrich Lippert and Horst Stubbe. Munich 1926; also in: The Oskar Panizza case. Edited by Knut Boeser. Ed. Hentrich, Berlin 1989, pp. 8-14.

- Sayings. (= Publications of the Panizza Society. Volume 1). Self-published, Berlin 1929.

- Pour gambetta. All drawings stored in the Prinzhorn Collection of the Psychiatric University Clinic Heidelberg and in the Regional Church Archive in Nuremberg. Edited by Armin Abmeier. Edition Belleville, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-923646-30-5

- Mama Venus. Texts on religion, sex and madness, edited by Michael Bauer. Luchterhand-Literaturverlag, Hamburg / Zurich 1992, Luchterhand collection 1025. ISBN 3-630-71025-5 .

- "A little prison and a little madhouse". A reading book. Edited by Michael Bauer and Christine Gerstacker. Allitera / edition monacensia, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-96233-106-1 .

Radio play adaptations

- The love council . Radio play in two parts with Rafael Jové, Josef Ostendorf, Peter Simonischek , Graham F. Valentine. Director: Ulrich Gerhardt . Production: BR 2014 ( download from BR radio play pool).

- The love council . With Wolfram Berger (editing, text design and playing of all roles) and Mattheus Sinko (vocals). Director: Peter Kaizar, Production: ORF 2014.

- The human factory . With Alois Garg, Gerd Anthoff, Thessy Kuhls. Director: Heinz von Cramer , Production: BR 1989.

- Dog Life 1892 . With Daniel Kasztura, Marianne Lochert, Grete Wurm , Thilo Prückner and others. Editing and direction: Heinz von Cramer . Production: BR 1987.

literature

- Michael Bauer: Oskar Panizza - Exile in Delusion: A Biography. Allitera / edition monacensia, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-96233-105-4 .

- Michael Bauer, Rolf Düsterberg: Oskar Panizza. A bibliography (= European university publications ; series 1, German language and literature ; 1086). Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-631-40530-8 .

- Michael Bauer: Oskar Panizza. A literary portrait . Hanser, Munich / Vienna 1984, ISBN 3-446-14055-7 and ISBN 3-446-13981-8 (also dissertation Munich 1983).

- Michael Bauer: Panizza, Leopold Hermann Oskar. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 20, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-428-00201-6 , pp. 30-32 ( digitized version ).

- Knut Boeser (Ed.): The case of Oskar Panizza. A German poet in prison. A documentation (= series German past , volume 37). Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-926175-60-5 .

- Uwe Böttjer: Oskar Panizza and the consequences. Images and texts for the re-performance of his love council. Koog House Press. Brunsbüttel oJ (early 1990s)

- Peter David Gilson Brown: Oskar Panizza. His Life and Works . Lang, Bern / New York / Frankfurt am Main 1983 (= American University Studies. Series 1 [= Germanic Languages and Literatures. Volume 27], ISBN 0-8204-0038-6 ; and European University Papers . Series 1: German Language and Literature . Volume 745), ISBN 3-261-03365-7 . At the same time revised version of Doghouse Jailhouse, Madhouse. A Study of Oskar Panizza's Life and Literature. Philosophical dissertation New York 1971.

- Peter DG Brown (ed.): The love council. A heavenly tragedy in five acts. Facsimile edition of the manuscript, a transcription of the same, furthermore the first edition of the “Love Council” as a facsimile, as well as “My defense in matters of 'The Love Council'” and materials from the second and third editions . belleville, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-936298-16-5 .

- Rolf Düsterberg: "The printed freedom". Oskar Panizza and the Zurich discussion team. (= European university publications ; series 1, German language and literature ; 1098) Lang, Frankfurt am Main and others. 1988, ISBN 3-8204-0288-8 ( dissertation Uni Osnabrück 1988).

- Bernd Mattheus : panizzajana. In: Oskar Panizza, dialogues in the spirit of Hutten. With a foreword by Heiner Müller, Panizzajana by Bernd Mattheus and contributions in the spirit of Panizzas by Karl Günther Hufnagel and Peter Erlach. Munich 1979.

- Bernd Mattheus: marginalia. In: Oskar Panizza, Der Korsettenfritz. Collected stories. Munich 1981.

- Oskar Panizza: The corset fritz. Collected stories. With a contribution by Bernd Mattheus. Munich 1981.

- Jürgen Müller : The Pazjent as a psychiatrist. Oskar Panizza's path from psychiatrist to inmate. Edition Das Narrenschiff, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-88414-291-7 .

- Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - attempt at an immanent interpretation. Tectum, Marburg 1999 (= Edition Wissenschaft, sub-series “Human Medicine”. Volume 264). At the same time medical dissertation in Würzburg (December 1990) 1991.

- Jürgen Müller: Panizza, Oskar. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (Eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1094.

- Dietmar Noering and Christa Thome: The whispering of stories or a conversation between Messrs. Raabe, Panizza and Klaußner along with interjections from some others . In: Schauerfeld. Communications from the Society of Arno Schmidt Readers, 3rd vol., No. 4, 1990 pp. 2–13.

- Oskar Panizza, Werner Schroeter, Antonio Salines: Love Council - film book . Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-921375-93-2 .

- Hans Prescher: References to the life and work of Oskar Panizzas. Epilogue. In: Oskar Panizza: The Love Council and other writings. Edited by Hans Prescher. Neuwied / Berlin 1964.

- Horst Stobbe : Oskar Panizza's literary activity. A bibliographical attempt. Private print, Munich 1925.

- Rainer Strzolka: Oskar Panizza. Stranger in a Christian society . Karin Kramer, Berlin 1993 ISBN 3-87956-115-X .

- Zvi Lothane : Romancing Psychiatry: Paul Schreber , Otto Gross , Oskar Panizza - personal, social and forensic aspects, in: Werner Felber (Ed.): Psychoanalysis & Expressionism: 7th International Otto Gross Congress, Dresden, 3rd – 5th Oct. 2008 , Verlag LiteraturWwissenschaft.de 2010, pp. 461–494.

Artistic arrangements

- Friedhelm Sikora: Thinking is always a bad thing - the inexorable disappearance of Dr. Oskar Panizza. no location 1990. Text / director's book in the Nuremberg City Library under FP 17.33

- Bernhard Setzwein : Oskar Panizza plays the Last Judgment with his carer Bruno in the Herzoghöhe sanatorium . World premiere: Tiroler Landestheater Innsbruck / Meran , May 27, 2000.

Web links

Online texts

- Works by Oskar Panizza at Zeno.org .

- Works by Oskar Panizza in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Works by and about Oskar Panizza at Open Library

- Digital copies and texts at ngiyaw eBooks

- Oskar Panizza in the Internet Archive

Library records

- Literature by and about Oskar Panizza in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by and about Oskar Panizza in the bibliographic database WorldCat

- Karlsruhe virtual catalog (KVK)

- Common Union Catalog (GBV)

life and work

- Alexander Bahar : The most horrific of all tortures (homage to Panizza's 150th birthday).

- Peter DG Brown: Oskar Panizza: His Life and Works (PDF, full text of the Panizza biography, English).

- Peter DG Brown: The Trials of Oskar Panizza: A Century of Artistic Censorship in Germany, Austria and Beyond. (PDF; 1.8 MB.) In: German Studies Review. 24/3, October 2001, pp. 533-556. The history of the court hearings for the love council .

- Rolf Düsterberg: Oskar Panizza (article in the "Database Writing and Image")

- European Court of Human Rights: Otto Preminger Institute versus Austria. (PDF; 46 kB. Judgment on the ban on film in Innsbruck; English).

- Rolf Löchel: If you don't want to be German, read it! In: literaturkritik.de No. 11, November 2003.

- Werner Robl: Short biography and catalog raisonné ( Memento from April 4, 2002 in the Internet Archive ).

- Herbert Rosendorfer: His mind tore ... (biographical essay).

- Kurt Tucholsky: Panizza. In: The world stage. September 11, 1919.

- Kurt Tucholsky: Oskar Panizza. In: freedom. July 11, 1920.

- Oskar Panizza in the Bavarian literature portal (project of the Bavarian State Library )

Remarks

- ↑ The correct pronunciation of the Italian name Panizza is [pa'nɪt͡sa], but the pronunciation ['pa: nɪt͡sa] has become commonplace.

- ↑ O. Panizza, A poet who lived umsunst. In: Friedrich Lippert, Horst Stobbe (Ed.): In memoriam Oskar Panizza. Munich 1926, p. 54.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: Panizza, Oskar. In: Werner E. Gerabek et al. (Ed.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. 2005, p. 1093.

- ↑ Hermann Bannizza: contributions to the history of gender Bannizza / Panizza. Neustadt an der Aisch 1966 (= special print German Family Archives. 32), p. 279 f.

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - Attempt at an Immanent Interpretation. Medical dissertation Würzburg (1990) 1991, pp. 1 and 31-43.

- ↑ Grandfather's obituary notice . Jürgen Müller: The Pazjent as a psychiatrist. Oskar Panizza's path from psychiatrist to inmate . Edition Das Narrenschiff, Bonn 1999, p. 19 and p. 214 (the information on p. 19, "left Lierna in the 17th century") is incorrect.

- ↑ Hermann Bannizza: contributions to the history of gender Bannizza / Panizza. Neustadt an der Aisch 1966 (= special print German Family Archives. 32), pp. 282 and 286.

- ↑ Philipp Carl Gotthard Karche (Ed.): Yearbooks of the Ducal Saxon Residence City of Coburg , 1853, p. 155f, online

- ↑ Michael Bauer: Oskar Panizza. A literary portrait. Munich / Vienna 1984, p. 64. At this point, Bauer describes the memoirs of Mathilde Panizza in the later version of the Dean Friedrich Lippert as “almost condensed into a religious pamphlet”.

- ↑ The evidence comes from the historical-critical complete edition of Eduard Mörike's works and letters (there numerous comments on the Speeth / Mörike relationship, especially in volumes 14 to 19); the entries Balthasar Speth and Peter Speeth in the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie , as well as from contemporary chronicles, court and state calendars. See also Karl Mossemann: The electoral court trumpeter Nikolaus Speeth and his descendants. Schwetzingen 1971, pp. 13, 15, 43 and 45 f.

- ↑ See M. Bauer, p. 63 f.

- ↑ They were published by the bookseller Friedrich Weinberger in Bad Kissingen. Mathilde was already around 70 years old at that time.

- ↑ Including from the Augsburger Postzeitung , the Münchener Neuesten Nachrichten and the Frankfurter Journal , see M. Bauer, p. 240.

- ↑ Again and again gold grains at literaturportal-bayern.de, accessed on September 28, 2021

- ↑ Bernd Mattheus: panizzajana. In: Oskar Panizza, dialogues in the spirit of Hutten. Munich 1979, p. 14.

- ↑ Michael Bauer: Oskar Panizza. A literary portrait. 1984, p. 94.

- ↑ Michael Bauer: Oskar Panizza. A literary portrait. 1984, p. 96.

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - Attempt at an Immanent Interpretation. Medical dissertation Würzburg (1990) 1991, p. 49 with note 131.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: Panizza, Oskar. In: Werner E. Gerabek et al. (Ed.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. 2005, p. 1094.

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - Attempt at an Immanent Interpretation. Medical dissertation Würzburg (1990) 1991, pp. 50 f., 78 f. And 82 f.

- ↑ A weighing of these possibilities can be found among others. in J. Müller, p. 201 f., and Peter DG Brown, p. 17.

- ↑ On the dubious symptoms of syphilis see also Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - attempt at an immanent interpretation. Medical dissertation Würzburg (1990) 1991, pp. 97-103.

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - Attempt at an Immanent Interpretation. Medical dissertation Würzburg (1990) 1991, p. 32 f.

- ↑ Michael Bauer: Oskar Panizza. A literary portrait. 1984, p. 90.

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - Attempt at an Immanent Interpretation. Medical dissertation Würzburg (1990) 1991, pp. 73-77.

- ^ Oskar Panizza: autobiography. In: Friedrich Lippert, Horst Stobbe (Ed.): In memoriam Oskar Panizza. Munich 1926, p. 11.

- ↑ Cf. for example Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - attempt at an immanent interpretation. Medical dissertation Würzburg (1990) 1991, pp. 237-240 ( consequences of 'illusionism': the orthography ) and more often.

- ↑ For example, Jens Malte Fischer describes the operated Jud ' as an "explosion of angry anti-Semitism as it was only achieved in this drastic form by the' striker '". ( German-language fantasy between decadence and fascism , in: Rein A. Zondergeld (Ed.): Phaïcon 3, Almanach der phantastischen Literatur , Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 1978, pp. 93-130.)

- ↑ So Alexander Bahar, The most horrible of all tortures .

- ↑ Quoted from J. Müller, p. 70.

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - Attempt at an Immanent Interpretation. Medical dissertation Würzburg (1990) 1991, p. 52 as well as 103-110 and 149.

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: Oskar Panizza - Attempt at an Immanent Interpretation. Medical dissertation Würzburg (1990) 1991, pp. 51 f. And 103-107.

- ^ Letter from O. Panizzas to Caesar Flaischlen, August 30, 1891, quoted from M. Bauer, p. 135.

- ^ Oskar Panizza: The crime in Tavistock-Square . In: Modern Life. A collector's book of Munich modernism. With contributions by Otto Julius Bierbaum, Julius Brand, MG Conrad, Anna Croissant-Rust, Hanns von Gumppenberg, Oskar Panizza, Ludwig Scharf, Georg Schaumberger, R. v. Seydlitz Ms. Wedekind. 1st row, Munich 1891.

- ↑ Bernd Mattheus: panizzajana. In: Oskar Panizza, dialogues in the spirit of Hutten. Munich 1979, p. 17 f.

- ^ Oskar Panizza: autobiography (1904), p. 13 f.

- ↑ Bernd Mattheus: panizzajana. In: Oskar Panizza, Dialogues in the Spirit of Hutten. Munich 1979, p. 18.

- ↑ Such a special position emphasizes z. B. Viktor Žmegač, History of German Literature from the 18th Century to the Present , Regensburg, Athenaeum, Vol. II., P. 225. Contemporaries such as Kurt Tucholsky and Theodor Fontane had already expressed this.

- ↑ The Love Council. In: News from the cauldron of madness fanatics and other writings. Edited by Michael Bauer. 1986, p. 66.

- ↑ Numerous published and private reactions can be found in K. Boeser, pp. 105–123.

- ↑ Quoted from M. Bauer, p. 154.

- ↑ Thomas Mann, Das Liebeskonzil , in: Das Zwanzigste Jahrhundert 5, 1895, Hbd. 2, p. 522.

- ↑ Protocol, p. 5 / SA Mchn., St. Anw. No. 7119 /. Quoted from: M. Bauer, Oskar Panizza, p. 17.

- ↑ Quoted from M. Bauer, p. 153.

- ↑ Die Gesellschaft 10, 1894, no.5, p. 703. Quoted from: M. Bauer, Oskar Panizza, p. 20.