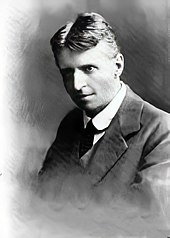

Otto Gross

Otto Hans Adolf Gross (born March 17, 1877 in Gniebing near Feldbach , Styria , † February 13, 1920 in Berlin ) was an Austrian psychiatrist , psychoanalyst and anarchist .

Life

Otto Gross was the only child of the well-known Austrian lawyer Hans Gross and his wife Adele. He spent the first four years of his life in the town where he was born. From 1881 he grew up in Graz , where his father worked at the university. Otto attended private schools and received instruction from private teachers .

After graduating from high school in 1894 at the 2nd kuk Staatsgymnasium in Graz, Otto Gross first studied zoology and botany at the University of Graz , but soon, at the request of his father, medicine . In the summer semester of 1897 he moved to the University of Munich . He then studied at the same time at the Universities of Strasbourg and Graz. In Graz he became Dr. med. PhD . In 1905 Gross submitted his habilitation thesis there. As a private lecturer in psychopathology , he gave a lecture on Freud's theory of ideogeneity in the winter semester of 1906/07 , which he worked out into a book.

In 1900 he was hired as a ship's doctor for the Hamburg German steamship company Kosmos , whose ships went to South America. It was on these trips that Otto Gross took cocaine for the first time - his addiction began. After his return he worked from 1901 to 1902 as a psychiatric trainee and assistant doctor with von Gudden in Munich and with Gabriel Anton in Graz. Because of his drug addiction, he was treated by Eugen Bleuler in 1902 in the Burghölzli Psychiatric Clinic in Zurich .

In 1903 Otto Gross married Frieda Schloffer, a niece of the philosopher Alois Riehl . The couple traveled to Ascona in 1906 , where Otto Gross attempted another withdrawal in the naturopathic facility on Monte Verità . There he provided the poison with which the settler Paulette Charlotte Hattemer took her own life. In Ascona he also met Erich Mühsam and Johannes Nohl , who influenced his further development. On September 1, 1906, the couple moved to Munich, and Otto Gross worked as an assistant doctor to Emil Kraepelin . Here I became acquainted with Johannes R. Becher as a patient.

During these years, Gross had intensive contacts with the Munich anarchist scene and the Schwabing bohemian . About referrals his wife also came Else Jaffé, born von Richthofen , with whom she went to boarding school, and her sister Frieda Weekley, née. from Richthofen to Munich. Gross had intimate relationships with both Richthofen sisters. At the beginning of 1907 the legitimate son Wolfgang Peter was born by Frieda Gross and at the end of the year the illegitimate son Peter. The mother Else Jaffé and her then husband Edgar Jaffé adopted the child. In 1908, Regina Ullmann Gross' illegitimate daughter Camilla Ullmann was born in Munich .

On April 26 and 27, 1908, the 1st Psychoanalytical Congress took place in Salzburg. This led to a little noticed, but momentous conflict: Otto Gross, one of the few psychiatrists who had publicly advocated Sigmund Freud's teaching for years, wanted to draw socio-political conclusions from it in a lecture. Freud, who had recently expressed himself contrary in his work The 'cultural' sexual morality and modern nervousness , countered this by saying that this was not the job of doctors, and ensured that Gross was pushed out of psychoanalysis and deleted from its annals . There was only one similar case in psychoanalysis: Wilhelm Reich's expulsion in 1934.

On May 6, 1908, Gross went to a treatment at the "Burghölzli" in Zurich, which was to consist of an addiction treatment and an analysis by Carl Gustav Jung . On June 17, 1908, he broke it off by escaping from the clinic. Jung later diagnosed dementia praecox .

Gross' lover and patient Sophie Benz became pregnant by him in October 1909, fell ill with psychosis in 1910 and committed suicide on March 3, 1911 in Ascona. Otto Gross went to the Casvegno asylum in Mendrisio (Switzerland) for treatment on March 6, 1911. On March 28, 1911, he transferred to the Viennese institution "Am Steinhof" with a transfer. In 1912 there was a wanted manhunt for murder and aiding and abetting suicide. In February 1913 Gross went to Berlin, where he joined the group around Franz Pfemfert , the editor of the action , joined and quarters with Franz Jung in Wilmersdorf found. On November 9, 1913, he was arrested here on charges of being a dangerous anarchist and expelled from Prussian territory. At the Austrian border, the father Hans Gross received his son and arranged for him to be admitted to the private insane asylum in Tulln near Vienna. Arrest, deportation and subsequent admission to the institution prompted Jung, Pfemfert and Mühsam to launch an international press campaign with the aim of freeing Gross.

In 1914 the Graz District Court decided on a board of trustees against him because of madness with the approval of the kuk regional court and his father was appointed as a curator. He immediately made sure that his son was transferred to the state insane asylum in Opava in Silesia. Here Otto Gross began to fight against his incapacitation, wrote several requests for a new examination and assessment of his mental state and finally achieved that he was released on July 8, 1914 as recovered. The next day Wilhelm Stekel took over the aftercare in a sanatorium in Bad Ischl . In the clinic, Gross met the nurse Nina Kuh and in Vienna also Marianne Kuh, the sister of the writer Anton Kuh .

In 1915 he was able to work briefly at the epidemic and barracks hospital of Ungvar County , then worked as a civilian doctor willing to storm a land storm and then as a land storm assistant doctor at the kuk epidemic hospital Vinkovci in Slavonia . After Gross' father died in 1915, Anton Rintelen was appointed his guardian, against which Gross defended himself legally.

From 1915 Gross worked for the magazine Die Freie Straße , to which Max Herrmann-Neiße , Franz and Richard Oehring , Georg Schrimpf , Oskar Maria Graf and Elsa Schiemann also contributed.

In 1916 his illegitimate daughter Sophie Kuh was born to Marianne Kuh. Because of his repeated relapses into drug addiction , the military finally disabled Otto Gross in May 1917 and unfit for military service. In 1917 he was in Prague - together with Franz Werfel - as a guest of Franz Kafka . They discussed the publication of a magazine called Leaves for Combating the Will to Power . In September 1917 the board of trustees (which had been ordered because of the waste and habitual use of neurotoxins) was also abolished, but was re-established in a limited form from December of the same year.

In the same year Gross contributed articles to the magazines Die Erde and Das Forum, and he moved between Graz, Vienna and Munich. In October 1919 he moved to Berlin, where he lived with Cläre and Franz Jung in Friedenau . On February 11, 1920, Otto Gross , who was sick and suffering from withdrawal symptoms, was found in a pass to a warehouse by friends - including Hans Walter Gruhle - and brought to a clinic in Pankow , where he died two days later. Franz Jung commented:

- "So he died quickly, not in a compromise, as was almost to be expected, no, detached from all the people who had surrounded him so far, in a gigantic surge of creativity and thought, people were just beginning to suspect, who this Gross actually was ... "

reception

Literary processing of the person

Gross' work, activities and, above all, his personal way of life - everything together had an effect on the works that were created within the literary scene in which he moved. As early as 1904, Frank Wedekind took Otto Gross as a model for the character of Karl Hetmann in the play Hidalla . And Franz Werfel in particular developed individual figures based on Otto Gross in three of his works:

- In the novel The Black Mass , Gross' derivation of sexual shame from the spirit of theocratic monotheism and the defeat of the feminine by prophecy take central positions. These are the positions that a cocaine-addicted scholar takes in a dual role as prophet and soul mage.

- In the Schweiger tragedy , which is about a psychotic watchmaker, Otto Gross was the model for the assistant Grund, who assists the psychiatrist Viereck. However, after the premiere on January 6, 1923, the assumption was expressed that Gross could also have been a role model for the protagonist Schweiger.

- And for the figure of Gebhardt in the novel Barbara or Piety , Werfel also used Gross as a model: As a private lecturer in psychiatry at an Austrian university, this Gebhardt wrote a paper on the movement of the Adamites in the Middle Ages.

Franz Kafka, who met Otto Gross on a night train journey from Budapest to Prague in July 1917 , did not so much directly process the person as an atmospheric influence : in the fragmentary novel Das Schloss , particles of reality appear that actually refer to places and People are related, and to whom Klaus Wagenbach writes in this context: “And finally, very clearly, the 'Herrenhof', also a café in Vienna (also called 'Hurenhof' by the writers), where Ernst Polak and Franz Werfel meet , Otto Pick , Egon Erwin Kisch and Otto Groß (sic!) Used to meet. "

Reception of the Scriptures

During his lifetime, Gross had an intense reception in German-speaking countries that extended to his writings and his socio-political work. The argument between father and son, which triggered an act of solidarity by his friends, attracted a lot of attention.

After his death Otto Gross was forgotten. The reason for this was primarily a Damnatio memoriae that Sigmund Freud imposed on him because Gross had called for the application of psychoanalytic knowledge to social problems. Gerhard M. Dienes, curator of the Graz exhibition The Laws of the Father , summarizes the organized forgetting:

- “Otto Gross belonged to the circle of Freud's apostate students. He did not put sexuality, but its conflict models (sic!) At the center of psychoanalysis. It was he who put the social and political significance of psychoanalysis in the foreground long before Wilhelm Reich . He was the first social critic among psychoanalysts. "

But even anarchists and writers who were in contact with him during Gross' lifetime did not discuss his ideas any further. An edition of the collected writings planned by Franz Jung for 1923 did not materialize.

Half a century later it hit the Berlin antiquarian Hansjörg Viesel "like a blow" when, after many years of thorough study of the history of anarchism, he first came across the name Otto Gross in a book by Carl Schmitt :

- “Every sovereignty acts as if it were infallible, every government is absolute - a sentence that an anarchist could literally have uttered, albeit for a completely different purpose ... All anarchist teachings, from Babeuf to Bakunin , Kropotkin and Otto Groß (sic!), revolve around one axiom: le peuple est bon et le magistrat corruptible. "

Viesel's find was the reason for Otto Gross to be rediscovered in German-speaking countries. Together with Hans Dieter Heilmann, he planned a two-volume annotated edition of the works of Otto Gross, which was to appear in 1973 with the anarchist Karin Kramer Verlag . It did not materialize either. Only after Martin Green's Else and Frieda (1976) and Emanuel Hurwitz 'Gross-Monographie (1979) had brought the author out of oblivion, the project could be realized - in a reduced form: in 1980 the writings selected by Franz Jung in 1923 finally appeared approx. 100 pages plus attachment.

Otto Gross Society

The gradual rediscovery of the work and the person finally resulted in the establishment of the Otto Gross Gesellschaft in Berlin in 1999 . Its statutory task is to research the work of Otto Gross. The question of which reasons resisted his reception in the decades after Gross' death should also be investigated. Since it was founded, the society has so far (2009) organized seven congresses, the results of which have been documented and published in detail.

exhibition

The reception in the 21st century also includes the exhibition The Laws of the Father in the City Museum Graz from October 4, 2003 to February 9, 2004. In 2003, the city was named European Capital of Culture : This exhibition featured the father-son couple from Graz Hans and Otto Gross at the center of problematic identity claims , whereby the people Sigmund Freud and Franz Kafka , who are added to the theme, knew both protagonists and their works. Like a model , the Graz City Councilor Christian Buchmann summarizes the intention of the exhibition in one sentence:

- “The conflict that Hans and Otto Gross fought becomes the pars pro toto (sic!) For the conflict between what is one's own and what is foreign, for dealing with foreignness within the individual and politics, and for the importance of father-son rivalries in politics. "

Fonts

The titles marked with (*) are contained in the anthology: Kurt Kreiler (Ed.): Otto Gross. From sexual hardship to social catastrophe. With an attachment by Franz Jung. Robinson, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-88592-005-0 (new edition: Nautilus, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-89401-357-5 ).

- 1901 Compendium of pharmacotherapy for polyclinicians and young doctors . Vogel, Leipzig.

- 1901 On the cardiorenal theories. In: Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 14, pp. 47-48.

- 1901 On the question of social inhibitions . In: Archives for criminal anthropology and criminalistics. 7, pp. 123-131.

- 1902 The cerebral secondary function . Vogel, Leipzig.

- 1902 On the Phyllogenesis of Ethics . In: Archives for criminal anthropology and criminalistics. 9, pp. 101-103.

- 1902 About the breakdown of ideas . In: Monthly magazine for psychiatry and neurology . 11, pp. 205-212.

- 1902 The emotional state of rejection . In: Monthly magazine for psychiatry and neurology. 11, pp. 359-370.

- 1903 Contribution to the pathology of negativism . In: Psychiatric-neurological weekly. 26, pp. 269-273.

- 1903 On the pathogenesis of specific delusions in paralytics . In: Neurologisches Zentralblatt. 17, pp. 843-844.

- 1904 On the differential diagnosis of negativistic phenomena . In: Psychiatric-neurological weekly. 37, pp. 354-353, 357-363.

- 1904 About the disintegration of consciousness . In: Monthly magazine for psychiatry and neurology. 15, pp. 45-51.

- 1904 The biology of the speech apparatus. In: General journal for psychiatry and psycho-forensic medicine. November 30, Berlin 1904.

- 1907 Freud's moment of ideogeneity and its meaning in Kraepelin's manic-depressive insanity . Vogel, Leipzig.

- 1908 parental violence . In: Maximilian Harden (ed.): The future. Vol. 17, pp. 78-80, (October 10, 1908). (*)

- 1909 About psychopathic inferiorities . Braumüller, Vienna / Leipzig (new edition: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller, 2006, ISBN 3-8364-0127-4 ).

- 1913 To overcome the cultural crisis . In: Franz Pfemfert (ed.): The action . Vol. 3, col. 384-387, (April 1913). (*)

- 1913 Ludwig Rubiner's "Psychoanalysis" . In: The Action. Vol. 3, col. 506-507.

- 1913 Psychoanalysis or we clinicians . In: The Action. Vol. 3, Col. 632-634.

- 1913 The influence of the general public on the individual . In: The Action. Vol. 3, Col. 1091-1095, (November 1913). (*)

- 1913 Notes on a New Ethics . In: The Action. Vol. 3, Col. 1141-1143, (December 1913). (*)

- 1913 note about relationships . In: The Action. Vol. 3, Col. 1180-1181, (December 1913). (*)

- 1914 Open letter to Maximilian Harden . In: The future. Vol. 22, pp. 304-306, (March 7, 1914). (*)

- 1914 About destruction symbolism . In: Central Journal for Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. 4 (1914), pp. 525-534.

- 1916 remark (with Franz Jung). In: The Free Street. No. 4, p. 2.

- 1916 On the conflict of the own and the foreign . In: The free road . No. 4, pp. 3-5. (*)

- 1919 orientation of the spiritual . In: Soviet. No. 5, pp. 1-5. (*)

- 1919 On the new preparatory work: About the lessons. In: The forum. 4, pp. 315-320. (*)

- 1919 The communist basic idea in the paradise symbolism. In: Soviet. No. 2, pp. 12-27. (*)

- 1919 On the problem: parliamentarism. In: The Earth. 22./23. Booklet, pp. 639-642. (*)

- 1919 Protest and morality in the unconscious. In: The Earth. No. 24, pp. 681-685. (*)

- 1919 On the functional intellectual education of the revolutionary. In: Council newspaper. Vol. 1 (1919), supplement, pp. 3-20. (*)

- 1920 Three essays on inner conflict (I: On conflict and relationship (*); II. On loneliness ; III. Contribution to the problem of delusion . Excerpt: two case studies . (*)) In: Treatises from the field of sexual research. Volume II, 3 (1920).

literature

- Raimund Dehmlow, Gottfried Heuer: Otto Gross. Catalog of works and secondary literature. Laurentius, Hannover 1999, ISBN 3-931614-85-9 . Constantly updated as an online bibliography .

- Martin Green: Else and Frieda. The Richthofen sisters. (Engl. orig. 1974) dtv, Munich 1976, ISBN 3-423-01607-8 .

- Emanuel Hurwitz : Otto Gross - Paradise seeker between Freud and Jung . Suhrkamp, Zurich 1979, ISBN 3-518-03305-0 .

- Franz Jung : Dr. med. Otto Gross. From sexual hardship to social catastrophe . In: Günter Bose, Erich Brinkmann (eds.): Grosz / Jung / Grosz. Brinkmann & Bose, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-922660-02-9 , pp. 101-155.

- Jennifer E. Michaels: Anarchy and Eros. Otto Gross' Impact on German Expressionist Writers. Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. a. 1983, ISBN 0-8204-0000-9 .

- Martin Green: Mountain of Truth. The counterculture begins. Ascona, 1900-1920. University Press of New England, Hanover NH 1986, ISBN 0-87451-365-0 .

- Hansjörg Viesel: Yes, Schmitt. Ten letters from Plettenberg. Gabler & Lutz, Berlin 1988.

- Jacques Le Rider : The End of Illusion. Viennese modernism and the crises of identity. Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-215-07492-3 .

- Nicolaus Sombart : The German men and their enemies. Carl Schmitt - a German fate between the male union and the matriarchal myth. Hanser, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-446-15881-2 .

- Michael Raub: Opposition and Adaptation. An individual psychological interpretation of the life and work of the early psychoanalyst Otto Gross. Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. a. 1994, ISBN 3-631-46649-8 .

- Lois Madison: The Grazer School of Thought on the Sprachapparat and Otto Groß 'Theory of a' Non-Organic Aphasia '(Mind Split). In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 13, 1995, pp. 391-397.

- Martin Green: Otto Gross. Freudian Psychoanalyst, 1877-1920. Literature and Ideas. Edwin Mellen, Lewiston NY 1999, ISBN 0-7734-8164-8 .

- Lois Madison (Ed.): Otto Gross. Works. The Graz years. Mindpiece, Hamilton NY 2000, ISBN 0-9704236-1-6 .

- Thomas Anz, Christina Jung (ed.): The case of Otto Gross. A press campaign by German intellectuals in the winter of 1913/14. Verlag LiteraturWwissenschaft.de, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-936134-02-2 .

- Gerhard M. Dienes, Ralf Rother: The laws of the father. Problematic identity claims. Hans and Otto Gross, Sigmund Freud and Franz Kafka . Exhibition catalog. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2003, ISBN 3-205-77070-6 .

- Wolfgang Buchner : Undercurrents of Consciousness. Otto Gross and the "associative nerve stream". Stadtmuseum Graz 2003. Catalog for the exhibition. The congress documentation since 1999 is bibliographed in the Otto Gross Society.

- Eveline Hasler : Stone means love. Regina Ullmann and Otto Gross. Novel . Nagel and Kimche, Zurich 2007.

- Hannelore Schlaffer : The intellectual marriage. The plan of life as a couple. Munich 2011, pp. 28–61 (on Otto Gross and Max Weber).

- Marcela Sánchez Mota: La otra Piel. Novela. Ciudad de México, 2014.

- Christine Kanz: Between knowledge and madness. Otto Gross in the metropolises of Vienna, Zurich, Munich, Berlin. In: Gabriele Dietze u. Dorothea Dornhof (ed.): Metropolitan Magic - Sexual Modernity and Urban Delusion. Vienna, Cologne, Weimar: Böhlau 2014, pp. 149–169.

- Gottfried M. Heuer: Freud's 'outstanding' Colleague / Jung's 'Twin Brother'. The suppressed psychoanalytic and political significance of Otto Gross. New York, 2017.

- Marie-Laure de Cazotte: Mon nom est Otto Gross. Novel. Paris 2018.

Web links

- Literature by and about Otto Gross in the catalog of the German National Library

- International Otto Gross Society eV

- Raimund Dehmlow: Secondary Bibliography

- Bernd A. Laska : Otto Gross between Max Stirner and Wilhelm Reich. Lecture at the 3rd International Otto Gross Congress 2002.

- Gottfried Heuer: biography

- Raimund Dehmlow: Life and Time

- Otto Gross in the Ticino Lexicon.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tessin Lexikon: Hattemer

- ↑ Gottfried Heuer: Interview.

- ↑ Exactly presented in the treatise by Bernd A. Laska : Otto Gross between Max Stirner and Wilhelm Reich . In: Raimund Dehmlow & Gottfried Heuer (eds.): 3rd International Otto Gross Congress. LiteraturWwissenschaft.de, Marburg 2003, pp. 125–162.

-

↑ See Karl Fallend, Bernd Nitzschke (Ed.): The "Fall" Wilhelm Reich. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / M. 1997;

Bernd A. Laska: Sigmund Freud versus Wilhelm Reich (excerpt from ders .: Wilhelm Reich. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1981, 6 2008) - ^ Zvi Lothane : Romancing Psychiatry: Paul Schreber , Otto Gross, Oskar Panizza - personal, social and forensic aspects, in: Werner Felber (ed.): Psychoanalysis & Expressionism: 7th International Otto Gross Congress, Dresden, 3rd – 5th Oct. 2008, Verlag LiteraturWwissenschaft.de 2010. pp. 461–494.

- ↑ Franz Jung. In: Brinkmann u. Bose (Ed.): Grosz / Jung / Grosz. Berlin 1980, p. 105.

- ^ Gerhard M. Dienes: The man Moses. In: exhibition catalog. Vienna 2003, p. 23.

- ^ Norbert Abels: Franz Werfel. 4th edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Norbert Abels: Franz Werfel. 4th edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2002, p. 62 f.

- ^ Gerhard M. Dienes: The man Moses. In: exhibition catalog. Vienna 2003, p. 23.

- ^ Gerhard M. Dienes: The man Moses. In: exhibition catalog. Vienna 2003, p. 27.

- ^ Klaus Wagenbach: Franz Kafka. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1978 (first edition 1964), p. 131.

- ↑ Documented and commented in: Christina Jung, Thomas Anz (ed.): The case of Otto Gross. Marburg 2002.

- ↑ See the chapter How Otto Gross is forgotten (made) from a published conference contribution by Bernd A. Laska (see web links).

- ↑ Gerhard M. Dienes: The man Moses or the torture of the machine. In: exhibition catalog. Vienna 2003, p. 20.

- ↑ Hansjörg Viesel: Yes, the Schmitt. Ten letters from Plettenberg. SupportEdition, Berlin 1988, p. 5.

- ↑ Carl Schmitt: Political Theology. 1922; quoted after the 8th edition. Berlin 2004, p. 60.

- ↑ See the chapter How Otto Gross was (re) discovered from a published conference contribution by Bernd A. Laska (see list of literature).

- ^ A b Christian Buchmann: Introduction. In: exhibition catalog. Vienna 2003, p. 9.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gross, Otto |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gross, Otto Hans Adolf |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian doctor, psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and anarchist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 17, 1877 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Gniebing , Styria |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 13, 1920 |

| Place of death | Berlin |