Georg Schrimpf

Georg Gerhard Schrimpf (born February 13, 1889 in Munich , † April 19, 1938 in Berlin ) was a German painter and graphic artist . He is one of the most important representatives of the New Objectivity art movement .

biography

Georg Schrimpf began to draw enthusiastically as a child, his favorite motifs were Indians. The artistic inclination found no understanding in the parental home, and certainly not any support. The stepfather urged the child in 1902 (in that year he lost his biological father) to do an apprenticeship as a confectioner in Passau . Georg completed it in 1905 and immediately went hiking. It took him through many German cities, including Belgium and France. He earned his living as a waiter, coal digger and baker.

In 1913 he became friends with the writer Oskar Maria Graf , also a trained baker. With him he traveled through Switzerland and Northern Italy. The two spent a few months in an anarchist colony in Ascona / Ticino, at times with Karl and "Gusto" Gräser on Monte Verità . A lifelong deep friendship developed. The first appraisals of Schrimpf's artistic activity came from OM Graf.

In 1915 Schrimpf moved to Berlin. At first he eked out his life as a worker in a chocolate factory. But now he started to paint intensely. He soon attracted the attention of the art expert, gallery owner and publicist Herwarth Walden , who exhibited Schrimpf's first oil paintings (Sturm 1916). They received a lot of attention. Schrimpf worked for the magazines “ Die Aktion ” and “ Der Sturm ” with woodcuts .

In 1917 he married the painter and graphic artist Maria Uhden , with whom he also had a lot in artistic terms. In the same year, the couple moved to Munich. Maria Uhden died in August 1918 of the consequences of the birth of her son Markus. Since 1918 Schrimpf has exhibited regularly in the New Art Gallery in Munich . As a member of the Action Committee of Revolutionary Artists, he took an active part in the Munich Soviet Republic . He also joined the November Group, where he participated in exhibitions in 1919, 1920, 1924 and 1929. Schrimpf published work a. a. in the Munich expressionist magazines Der Weg . The book box and the sickle . In 1920 Schrimpf exhibited for the first time at the Neue Sezession in the Glaspalast in Munich . A year later he became a member of this group. She particularly appealed to him, because here he didn't feel pushed in a certain direction. In 1922, again in Italy, he came into contact with the artist group around the Italian magazine Valori Plastici ; Carlo Carrà then wrote a monograph on Schrimpf. From 1926 to 1933 he taught at the Munich School of Applied Arts .

In 1932 the group Die Sieben founded and began a traveling exhibition . which, in addition to Georg Schrimpf, also included the artists Theo Champion , Adolf Dietrich , Hasso von Hugo , Alexander Kanoldt , Franz Lenk and Franz Radziwill .

In 1933 he was appointed associate professor at the State University for Art Education in Berlin-Schöneberg. His teaching activity ended in September 1937 by order of Bernhard Rust , the Prussian Minister for Science, Art and Education . The reasons given were that Schrimpf had been a member of the Communist Party from January to April 1919 and of the KPD-affiliated Red Aid for a year in 1925/26 .

As a full member of the German Association of Artists , Georg Schrimpf took part in the last DKB annual exhibition at the Hamburger Kunstverein . The attitude of the Nazi regime towards the person and work of Georg Schrimpf throws a significant light on the contradictions of the so-called “art policy”. He was considered red and therefore automatically as "degenerate". When, on the basis of a decree by the Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels , around 16,000 pictures were removed from German museums as being worthless and degenerate , 33 works by Schrimpf were also among them. At the same time, some great Nazi figures were among the collectors of Schrimpf paintings, such as Reich Ministers Hess and Darré . In July 1937, in the year before his death, he was defamed again in the Nazi exhibition Degenerate Art .

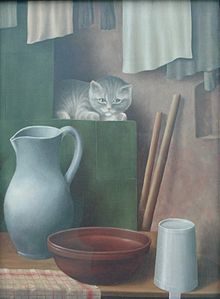

In 1995 the Deutsche Bundespost issued a two-D-Mark special postage stamp in honor of Schrimpf as part of the series "German Painting of the 20th Century", using his painting "Still Life with a Cat" from 1923 (see illustration above right).

plant

Schrimpf was self-taught. From childhood he drew obsessively, from his head and from templates, and copied pictures that he particularly liked. In 1913, after his return from Ascona, he attended a painting school in Munich for eight days. His self-doubts were so strong that he hid his work from strangers. Except in front of his friend, the writer Oskar Maria Graf (like Schrimpf, a former baker). He sent some papers to Berlin for "action". They were accepted immediately. Schrimpf was surprised that others could find interest in his work at all. Now his artistic career began. In addition to the publicist and art patron Herwarth Walden ( Der Sturm / Aktion ), his early supporters also included the art historians and critics Franz Roh and Werner Haftmann .

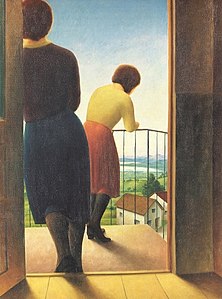

Schrimpf mainly works with charcoal, chalk, oil and woodcut. His work is characterized by clear outlines and delicate coloring. An immense calm emanates from every picture - especially in contrast to Schrimpf's restless wandering life. His motifs are mainly women and landscapes. He paints women in front of the mirror, women at the window, women looking into the distance full of expectation. His landscapes are deserted, pure nature (e.g. the Easter lakes ).

Schrimpf did not seem to have touched the artistic trends of his time. There is no social criticism, no daily politics, no exciting city life, no social problems. This, too, reveals a strange ambivalence in his personality. Because Schrimpf had not only dealt with leftist ideas early on, but made friends. He was a member of the SPD for a year . When he heard Erich Mühsam speak , he was so impressed that he joined his group “Tat”. He always sympathized with "revolutionaries". But in his work he created a counter-world, a world that he probably dreamed of as the goal of a successful revolution.

Working in museums

- Museum of Modern Art , New York

- New National Gallery Berlin

- East Frisian State Museum , Emden

- Kunstmuseum Basel , Basel

- Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus , Munich

- Pinakothek der Moderne , Munich

- Municipal art gallery , Mannheim

- North Carolina Museum of Art , Raleigh

- From the Heydt Museum , Wuppertal

- Museum Ludwig , Cologne

- Museum of the Electoral Palatinate of Heidelberg

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Gunzenhauser Museum , Chemnitz

- Moritzburg Art Museum Halle (Saale)

gallery

literature

- Olaf Peters : Schrimpf, Georg. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3 , pp. 549-551 ( digitized version ).

- Renate Hartleb : Georg Schrimpf . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1984.

- Georg Schrimpf: A trip around the world in 16 pictures. Curt Steinitz Verlag, Munich undated (1924).

- Oskar Maria Graf : Ua-Pua! Indian seals. With 30 chalk drawings by Georg Schrimpf. Franz Ludwig Habbel Verlag, Regensburg 1921.

- Oskar Maria Graf : Georg Schrimpf. Published by Klinkhardt & Biermann, Leipzig 1923 (Young Art, Volume 37).

- Oskar Maria Graf : A baroque painter portrait in: Mitmenschen Allitera Verlag, Munich, ISBN 978-3-86906-705-6

- Georg Schrimpf. Introduction by Matthias Pförtner . Rembrandt Verlag, Berlin 1940.

- Wolfgang Storch : Georg Schrimpf and Maria Uhden. Life and work. With a catalog raisonné by Karl-Ludwig Hofmann and Christmut Praeger. Charlottenpresse, Frölich & Kaufmann, Berlin 1985.

- Adam C. Oellers : artist, friend and contemporary. For portraits of Georg Schrimpf and his circle in the 20s. In: Aachener Kunstblätter , Volume 54/55, 1986/87, pp. 283-292.

- Ulrich Gerster: Continuity and Break. Georg Schrimpf between the Soviet Republic and Nazi rule. In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte , Volume 63, Issue 4, 2000, pp. 532–557.

- Helga Margarete Heinrich: Ostracized, not “degenerate”. The painter Georg Schrimpf (1889–1938). In: Literature in Bavaria . Quarterly magazine for literature, literary criticism and literary studies, Issue No. 98, December 2009, ISSN 0178-6857 , pp. 35–47.

- Ulrich Gerster: The deputy protégé. Georg Schrimpf and his painting "Mädchen vor dem Spiegel". In: Uwe Fleckner (Ed.): The ostracized masterpiece. The fate of modern art in the “Third Reich”. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-05-004360-9 , pp. 335–363.

Individual evidence

- ↑ s. Vita Georg Schrimpf in Emilio Bertonati: New Objectivity in Germany . Schuler Verlag, Herrsching 1988. ISBN 3-88199-447-5 (p. 94)

- ^ Carlo Carrà: Georg Schrimpf . Editione Valori Plastici, Rome 1924

- ↑ 1936 banned images . Exhibition catalog for the 34th annual exhibition of the DKB in Bonn, Deutscher Künstlerbund, Berlin 1986. (p. 99, exhibiting DKB members 1936)

- ^ Ernst Klee : The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-039326-5 , p. 547.

Web links

- Literature by and about Georg Schrimpf in the catalog of the German National Library

- Short biography on artnet - accessed August 2, 2010

- Georg Schrimpf on kunstaspekte.de

- Georg Schrimpf in HeidICON Illustrations of the Simpl

- Works by Georg Schrimpf in the Moritzburg Art Museum

- blouinartsalesindex.com

- SZ report on the exhibition "My friend the painter in the Murnau Castle Museum

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schrimpf, Georg |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schrimpf, Georg Gerhard (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German painter and graphic artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 13, 1889 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Munich |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 19, 1938 |

| Place of death | Berlin |