Christmas

Christmas , also known as Christmas , Christian Feast or Holy Christian , is the feast of the birth of Jesus Christ in Christianity . The festival day is December 25th , Christmas Day , also the solemn feast of the birth of the Lord (Latin Sollemnitas Nativitatis Domini or In Nativitate Domini ), whose celebrations begin on the eve, Christmas Eve (also Christmas Eve, Christmas Eve, Christmas Eve, Christmas Eve). December 25th is a public holiday in many states . In Germany , Austria , the Netherlands , Switzerland and many other countries, the second Christmas holiday is December 26th, which is also celebrated as St. Stephen's Day.

Christmas is usually celebrated in the family or with friends and with mutual gifts, called gift giving . In German-speaking countries and some other countries, the gift giving usually takes place in the evening on December 24th and is seen as the special part of Christmas. In English-speaking countries it is customary to give presents on the morning of Christmas Day. In the giving ritual, reference is made to mythical gift bringers such as the Christ Child or Santa Claus , some of which are also played. Such rites, like the festival as a whole, serve to strengthen family relationships. Many countries associate other customs of their own with Christmas.

Attending a church service on Christmas Eve, at night or on the morning of December 25th is part of the festival tradition for many people; in Germany this applies to a fifth of the population (2016 and 2018).

In Western Christianity, Christmas is one of the three main festivals of the church year with Easter and Pentecost . December 25th has been recorded as a religious holiday in Rome since 336 . How this date came about is unclear. The influence of the Roman sun cult is discussed : Emperor Aurelian had set December 25, 274 as the nationwide festival day for the Roman sun god Sol Invictus ; early Christians drew parallels between this sun god and "Christ, the true sun" (Christ verus Sol) .

The custom of giving presents to children for Christmas in today's usual way dates back to the Biedermeier period and was initially limited to upper-class circles, because only these had the living room used on a stage available, could afford a private Christmas tree and choose children's gifts from the increasingly diverse range of toys .

etymology

The High German expression Christmas goes on a Middle High German , adjectival phrase wîhe seam or ze wîhen (s) approached back whose frühester document in the collection of sermons Speculum Ecclesiae place (in 1170).

"Diu gnâde diu anegengete see you near dirre: from diu heats you diu wîhe draws near."

"Grace came to us that night: hence it is called the holy night."

The verses from a long poem by the Bavarian poet Spervogel (around 1190) date from the same period :

“He is violent unde starc, / who was born when near. / there is the holy Krist. "

"He is mighty and strong, who was born on the consecrated [hallowed] night: that is the holy Christian."

The expression remained limited to the Upper German area until the 13th century and has only been documented as wînahten in the Central German dialects since the end of that century . In addition, christtag comes across as a synonym in Central Germany from Thuringia and Upper Hesse to Westphalia to Luxembourg and Lorraine. In Middle Low German , instead, the words kersnacht “Christnacht” and kerstesmisse “Christmesse” (cf. English Christmas ) are found instead , only from 1340 onwards wewachten (m.) . In eastern northern Germany, the mnd. jûl received more recently than Jul .

The adjective Old High German and Old Saxon wîh , Middle High German wîch is derived from Germanic * wīʒja, wīhaz 'holy, consecrated, numinos' from the Indo-European word root * ueik 'separate, separate, consecrate' and resulted in a meanwhile uncommon soft 'holy' in New High German . For its part, the weak verb wîhen (ahd. And mhd. Identical, from Germanic * wīʒjan, wīhijaną ) and finally the new high German consecrated were derived from this adjective . Substantivating the adjective resulted in Old Saxon and Old High German wîh 'temple', Old English wēoh, wīg ' idol ' and Old Norse vē 'sanctuary, temple, place of justice' (cf. the Nordic deity Vé ). In addition, wîh is probably related to the Latin victima 'sacrificial animal' and Old Lithuanian viešpilas 'holy mountain'. The second part of the word approached links on the one hand to the old division of time from day to night (cf. English fortnight "fourteen days"), on the other hand, the plural refers to several holidays - perhaps with reference to the early church tradition of the Twelve Days of Christmas from 25 December to Epiphany on January 6th or the European custom of the rough nights . So the compound word can be translated as the holy nights .

Theodor Storm coined the impersonal verb christmas . In his poem from Knecht Ruprecht it says in the opening and closing lines:

I come from outside of the forest;

I have to tell you, it's very Christmassy!

Basics in the New Testament

The vast majority of historical Jesus research comes to the conclusion that Jesus of Nazareth lived as a person in his time. His birth in Bethlehem is told in two of the four Gospels: Matthew and Luke each independently precede their Gospel with a childhood story with legendary elements. From a post-Easter perspective, the stories want to make it clear that Jesus Christ was the promised Messiah from the beginning, even as a newborn child .

Luke and Matthew

The representation that is more common today comes from the Gospel of Luke :

“But it happened in those days that Emperor Augustus issued the order to enter the whole world in tax lists. This record was the first; at that time Quirinius was governor of Syria. Everyone went to their city to be registered. So Joseph also went up from the city of Nazareth in Galilee to Judea, to the city of David, which is called Bethlehem; for he was of the house and tribe of David. He wanted to be registered with Maria, his fiancée, who was expecting a child. It came to pass, while they were there, that the days for her to give birth came to pass, and she gave birth to her firstborn son. She wrapped him in diapers and put him in a crib because there was no room for her in the hostel. "

This is followed by Luke's preaching to the shepherds ( Lk 2.8–20 EU ) and the presentation of Jesus in the temple according to Jewish regulations ( Lk 2.21–40 EU ). This was preceded by the proclamation of Jesus to Mary and parallel to this the proclamation and the birth of John the Baptist ( Lk 1, 3–80 EU ).

According to the family tree of Jesus ( Mt 1,1–17 EU ), the Gospel of Matthew speaks rather casually of the birth of Jesus Christ, in connection with Joseph's doubt about his fatherhood, to whom an angel in a dream hinted at the importance of the child of Mary gave ( Mt 1,18-25 EU ). It depicts the worship of the newborn by the magicians ( Mt 2 : 1–12 EU ) and then the flight to Egypt , the murder of Herod and the return of Joseph with Mary and the child to Nazareth ( Mt 2, 13–23 EU ).

Gospel of John and Paul

In the Gospel according to John and in the letters of Paul the birth of Jesus is not described, but the birth, his public appearance and his death on the cross are assumed. The Gospel of John interprets the incarnation of the Son of God in theological and poetic way :

“The true light that illuminates every human being came into the world. He was in the world and the world became through him, but the world did not recognize him. He came into his own, but his own did not accept him. / But to all who received him he gave power to become children of God, to all who believe in his name, who were born not of blood, not of the will of the flesh, not of the will of man, but of God . / And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we saw his glory, the glory of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth. "

Also John the Baptist testifies and confirms this statement as “forerunner of Jesus” in Joh 1,6–8 EU and 1,15 EU .

In Paul’s faith in Jesus Christ is not presented in narrative form, but theologically condensed. The incarnation of the Son of God is preached as kenosis , as "alienation" and "humiliation", so in the letter to the Philippians :

“Be disposed towards one another as it corresponds to the life in Christ Jesus: / He was equal to God, but did not hold fast to being equal to God, / but he emptied himself ( ancient Greek ἑαυτὸν ἐκένωσεν heautòn ekénosen ) and became like a slave and equal to people. / His life was that of a man; he humbled himself and was obedient until death, until death on the cross. / That is why God exalted him above all and gave him the name that is greater than all names, / so that everyone in heaven, on earth and under the earth bow their knees before the name of Jesus / and every mouth confesses: 'Jesus Christ is the Lord '/ to the glory of God the Father. "

Theological statement

The popular “Mary put the child in a manger because there was no place for her in the inn” ( Lk 2.7 EU ) thus corresponds to the sentence of the Gospel of John “He came into his own, but his people did not receive him” ( Joh 1,11 EU ) and the " incarnation " and " alienation ", the "becoming equal to men" of Pauline theology ( Phil 2,7 EU ). The statements of the Gospels about birth characterize the entire mission of Jesus Christ as God's saving act for the redemption of people through his Son , from Jesus' birth to his execution on the cross : "Even in his birth, Jesus is (or: becomes) the Son of God" , emphasize Matthew and Luke by placing the Christmas prehistory in front of their gospel.

Origin of other Christmas motifs

Child of God and Child God

The motive of the divine procreation of great men and heroes preceded Christianity in religious history . From it the belief in a virgin birth arose logically, so to speak , which can be found in ancient Iran as the virgin conception of the eschatological savior of the Zoroastrian eschatology Saoschjant as well as implicitly in the Danaë myth and the procreation legends about Plato or Alexander the Great . Of course, it always remained with a bodily conception of the respective Son of God , who was not always presented as the savior of the world.

The idea of the annual rebirth of a god was also known from Egyptian and Greek mythology and was associated with the cycle of seasons and vegetation , especially in the myths about Osiris and Dionysus .

Karl Kerényi characterized the first phase of Dionysus' life as follows: “The divine child in the cave, surrounded by feminine care. In that phase it was revered as the secret content of the grain wing. ”An important source for this are the Orphic hymns. In the 46th Orphic Hymn , Dionysus is addressed by the nickname Liknítes (Λικνίτης), derived from ancient Greek λίκνον líknon "grain wing ", a cult object of the Dionysus mysteries. Dionysus Liknites was worshiped in Delphi, where he was the main deity in the absence of Apollo during the winter months. The hymn speaks of sleeping and awakening, or the birth of Dionysus. Orpheus connects the imagery of blossoming with the plant world. The corresponding ritual of the Mysteries was likely to have involved bringing in a grain wing and revealing its contents. The 53rd Orphic Hymn shows unusual elements, which can probably be explained by the fact that a Phrygian cult was associated with Dionysus. Only here within the Orphic Hymns is Dionysus referred to as a chthonic deity : he sleeps in the underworld (the halls of Persephone ) and is woken up by the cult participants, corresponding to the beginning of vegetation in spring. In the Orphic Fragments, Dionysus is identified with Phanes , who is born in a cave. Diodorus was also familiar with this equation of Phanes and Dionysus, as well as the fact that "some" identified Osiris and Dionysus. The Suda According to some dying and resurrecting gods could be equated: Osiris, Adonis and Aion .

Authors of the early imperial era mention a birth festival of the Egyptian deity Osiris on January 6th and a festival in honor of Dionysus on the island of Andros on the same day.

An element of the mysteries of Eleusis is known through the Philosophumena : a nocturnal ritual culminated there in the exclamation "a holy son the mistress gave birth to, Brimo the Brimos". In ancient times Brimo could be identified with Persephone, her child Brimos with Dionysus.

The Cypriot bishop Epiphanios of Salamis wrote in the 4th century AD that the birth of Aion was celebrated in Alexandria at the same time as the Christian festival of Epiphany (i.e. on the night of January 5th to 6th) in the sanctuary of Kore . With her admirers, Kore had the title "virgin", which Epiphanios, probably incorrectly, understood in the sense of the Christian dogma of the virgin birth. The Ugaritic deity Anat, whose cult came to Egypt early on, could be called "virgin" to emphasize her youth and fertility, and Isis was "virgin" when identified with the constellation Virgo; both goddesses were not considered sexually abstinent. According to Pausanias, Hera renews her virginity every year by bathing in a holy spring. What Epiphanios described was an originally Dionysian cult that had taken up elements of other cults in the cosmopolitan environment of Alexandria, possibly also Egyptian and Christian ideas.

According to Carl Gustav Jung and Karl Kerényi , the “child god” has an archetypal quality. According to the dialectical formula “smaller than small, but bigger than big”, he is closely related to the adult hero. With the initial abandonment of the child, its “unsightly beginnings”, the “mysterious and wonderful birth” and the “insurmountability of the child” are connected. Jarl Fossum emphasizes that a newborn child stands for the future. The idea that Zeus transferred rule over the gods to the Dionysus boy has therefore been claimed by various rulers for themselves, combined with the idea that a new age would begin with their assumption of rule. Emperor Antoninus Pius had coins minted as the “new Dionysus” that refer to the rebirth of the phoenix and the deity Aion.

The Christmas story is not (at least not explicitly) located in a cave in the Gospels. But the Bethlehem natal cave tradition is old compared to other Christian pilgrimage traditions:

- Justin Martyr was the first author to mention the cave birth of Christ around AD 150 and justified it biblically with the Septuagint version of Isa 33:16: "[A righteous] will dwell in a high cave of a mighty rock." known that the Mithras worshipers taught the birth of their deity out of hard stone in a cave; for him the resemblance to the Bethlehem birth cave tradition was a diabolical delusion.

- Also in the middle of the 2nd century, the Proto-Gospel of James made the birth scene in the cave legendary. This work was widely read in late antiquity and the Middle Ages and had a great influence on Christian art.

- In the middle of the 3rd century a cave near Bethlehem had become a Christian pilgrimage site, which Origen probably knew from his own experience. "And what is shown there is a well-known thing in these areas even among non-Christians, so that they know that Jesus, who was worshiped and admired by Christians, was born in this cave."

- There is tension about what Hieronymus , who lived in Bethlehem, wrote in retrospect in the 4th century: “A holy grove of Thammuz, also called Adonis , shaded our Bethlehem, the most sublime place in the whole world, from which the psalmist writes: Truth sprouted out of the earth . The lover of Venus was mourned in the cave in which Christ once whimpered as a child. "

- For the Christian cult, the Bethlehem Cave was claimed by Emperor Constantine in 326 by having a basilica, the Church of the Nativity, built over it.

Whether Christmas is to be interpreted as the adoption of older ideas from other religions or as a suppression of parallel cults remains a matter of dispute. The influence of the ancient depictions of Dionysus, Isis , Osiris and their son Horus on Christian iconography seems plausible.

Promise of the royal child as a sign of hope

In the prophecy of a royal child in the book of Isaiah, chapter 7, the ancient Jewish translation into Greek ( Septuagint ) deviates several times from the Hebrew text, which is normative in Judaism ( Masoretic text ). These deviations are underlined in the following text.

“That is why the Lord himself will give you a sign; see, the virgin will be pregnant and give birth to a son ... "

Instead of ancient Greek παρθένος parthénos "virgin", the Masoretic text offers Hebrew עַלְמָה 'almāh "young woman, girl, servant." However, "virgin" is not as strongly emphasized in the Septuagint text as one might assume in view of the Christian history of interpretation, rather the word can generally designate a "young woman of marriageable age". In the Septuagint translation of Gen 34.3, the raped Dina is referred to as parthénos . In the context of Isa 7, the translator probably preferred parthenos to ancient Greek νεᾶνις neãnis "girl" because this latter word has the connotation "servant" and should be emphasized that a young woman of high social standing gives birth to the royal child.

A similar, but probably unrelated, idea can be found in the fourth eclogue of the Roman poet Virgil . The poet heralds an imminent turning point. The coming golden age is symbolized in the birth of a boy:

|

|

Virgil dated the fourth eclogue to the year 40 BC. BC (Consulate of Asinius Pollio) and thus in the time of the Roman civil wars after the assassination of Caesar. Virgil was a party: Octavian , the young emperor, celebrated his collection of pastoral poems without giving his name. In this cycle, the fourth eclogue heralded the beginning of a paradisiacal time under Octavian's rule. Was Eclogue 4 a kind of mystery (? From which boys persuaded the poet), so put Virgil in the Aeneid the Anchises an answer in the mouth, so Niklas Holzberg : "This is the man, this is he who you how often hear, it is promised, Augustus Caesar, the Son of God, who will establish the Golden Age anew for Latium ... "

The text of the 4th eclogue is dark. The "new offspring" ( nova progenies ) is mostly interpreted in the light of Hesiod's conception, according to which a new human race arises in every age. Others identify the “offspring” with the boy ( puer ) addressed in the further course of the poem ; that remains ambivalent. In the Christian adaptation of this verse, the individual interpretation predominates: the child is equated with Christ (e.g. Lactantius ). But there is also the collective interpretation of the church or the gender of the baptized. The late antique poet Prudentius combined the formulation of Virgil with a concept of Paul of Tarsus : Christ is the new Adam, in whose resurrection body the Christians participate.

The magicians and the star

The people referred to in common Bible translations as "sage" (Lutherbibel) or "Sterndeuter" (uniform translation, Zurich Bible) are ancient Greek μάγοι mágoi in the original text of the Gospel of Matthew , "Wise men and priests who understood star and dream interpretation as well as other secret arts [ en]. "

The classical philologist and religious researcher Albrecht Dieterich suspected that the motif in the special property of the Gospel of Matthew, that magicians from the east pay homage to the newborn king of the Jews, was neither legend nor myth; "It is the effect of a generally exciting and long-known historical event." In 66 AD, the Armenian King Trdat I (Tiridates) traveled to Rome and paid homage to Emperor Nero with Proskynesis . Cassius Dio , Suetonius and Pliny the Elder report on this . Tiridates was referred to by Pliny as a “magician” in this context: “The magician Tiridates had come to him and brought the triumph over Armenia in person ... He had brought magicians with him and even initiated 'Nero' into the meals of the magicians, nevertheless if he was not able to ... learn this art. ”Trdat returned to his homeland in another way, as did the magicians in the Gospel. Dieterich said that this historical event must have orally "circulated in a long tradition and gradually formed" in the population. He combined this with a late dating of the Matthean childhood stories to the 2nd century. It was only at this time that the story of the homage of the magicians was "indented" into the Gospel of Matthew.

The astrology and astronomy historian Franz Boll also pointed out that the episode with the star was designed as a miracle story and was based on the ideas of the time that a star appears in the sky with the birth of a person, which is extinguished again with that death. According to ancient beliefs, the more important the person in question became, the bigger and brighter the star was.

For further suggestions of an astronomical or astrological interpretation of the star motif, see the main article Star of Bethlehem .

History of the fixed date

The date of birth of Jesus Christ is not mentioned in the New Testament and was unknown to early Christianity , which celebrated the days of death of its martyrs . Clement of Alexandria reported around 200 about speculations of different Christian groups in Egypt: the Basilidians designated January 6th or 10th as the day of the baptism of Jesus, who according to their conviction ( Adoptianism ) was also the day of his birth as Son of God, other Egyptian Christians held April 19, April 20, May 20, or November 18 the birthday of Jesus Christ.

December 25th as the day of the birth of Jesus Christ was explicitly mentioned for the first time by Furius Dionysius Filocalus in his chronograph from 354 , which is based on Roman sources from the year 336, a year before the death of Constantine and at a time of the rise of Christianity. A directory of the Roman consuls contains the entry: "Christ was born during the consulate of C. Caesar Augustus and L. Aemilianus Paulus on December 25th, a Friday, the 15th day of the age of the moon". In this Roman source, which has some internal contradictions, the date is, in the opinion of Hans Förster, also to be understood as a liturgical feast day, so that the year 354 is the terminus ante quem for the western church Christmas on December 25th. In the commentary on Daniel by Hippolytus of Rome (170–235) there is a later insertion that also indicates December 25th as the date of birth of Jesus Christ. According to a Christmas sermon by Jerome (347-420), the festival in Rome is said to have been celebrated on December 25th from the beginning. According to Susan K. Roll, the oldest liturgical historical testimony that Christians celebrated the birthday of Jesus as a feast is a sermon by Optatus von Mileve (361) on the murder of children in Bethlehem . Ambrose of Milan wrote the hymn Intende qui regis Israel , which contains Christmas motifs and is shaped by the Christology of the Council of Nicaea . For northern Italy, the date for the end of the 4th century is documented by Filastrius of Brescia, among others . The Synod of Saragossa testified in can. 4 the date for the year 380 in Spain. There is as yet no evidence of Gaul for this period. It was not until the 6th century that Gregory of Tours called it .

The fact that December 25th prevailed as a fixed date is explained in the specialist literature with two theories that have emerged since the 19th century and which are not mutually exclusive:

- the calculation hypothesis

- the religious-historical hypothesis.

Calculation hypothesis

In the absence of further biographical data, one possibility was to trace the feast of the birth of the Savior back to the day of Christ's crucifixion. The day of death was known from the Gospel of John as the day before Passover , the 14th of Nisan . Around the year 200 AD, the church writer Tertullian equated this 14th Nisan of the Jewish lunisolar calendar with the 25th of March of the Roman solar calendar, which also corresponded to the spring equinox and was identified by the early Christians with the first day of creation .

In the work De pascha computus , written in 243, the birth of Jesus was placed on the day of the creation of the world, March 25, a Wednesday. On the other hand, the world chronicle (Χρονογραφίαι, Chronographíai ) by Julius Africanus , which went up to AD 221 , designated March 25 as the day of the Passion and Conception of Mary , which resulted in a date of birth at the end of December. Both dates were based on the close connection between the Incarnation of Christ and his Passion, which would ultimately have been reflected in the symbolic identification of the two events.

The calculation hypothesis , initially advocated by Louis Duchesne , and later by Hieronymus Engberding , Leonhard Fendt and August Strobel , is based on the notion of ancient Jewish writings that great patriarchs died on the same day of the year they were born. Because God only approves of what is perfect, so let his outstanding heralds only live full years of life on earth. This was especially true of Isaac , who became Jesus' example for Christians. For Jesus, too, the beginning and end of his earthly life would have been placed on the same date, namely the 14th Nisan of the year 30, which would have corresponded to March 25th. However, one must equate the beginning of one's life with the conception of Mary. That resulted in December 25th as the date of birth, which accordingly would have emerged organically from John's Passion Report. The pagan Sol Invictus was only a secondary reason and not the primary impetus for the choice of the date.

Religious historical hypothesis

After a first in 1889 and 1905 by Usener Hermann represented religious-historical hypothesis Christmas date is in response to the cult committed birthday of the Roman Empire of God Sol Invictus arose, the Emperor Aurelian put in 274 on the winter solstice on December 25; on the same day of the year the birth of Mithras was also celebrated on Yalda night . That would lead to an introduction at 300. This corresponds to roughly simultaneous comparisons of Christ and the sun and the fact that "the Christmas celebration in Rome comes when the sun cult reaches its climax". When Emperor Constantine the Sunday declared a "venerable day of the Sun" by decree for public holiday, this was a regulation that various religions for trailers was a consensus, among Christians and worshipers of Mithras and Sol Invictus.

The idea of Christ as the true Sol Invictus , the victor over death could be systematized into a harmonious order of the calendar: After the solar year was ordered so that the time of the autumnal equinox on September 24, the proclamation and conception of John the Baptist , to Summer solstice on June 24th whose birth took place on the spring equinox the conception of Jesus and on the winter solstice his birth took place.

The School of Religious History identified pagan precursors for Christian festivals and rituals. In relation to Christmas, this interpretation was also received by the church in a softened form. The basis was a study by Bernard Bottes from 1932, who argued that pre-Christian solstice celebrations were "a stimulus and starting point", but not the cause of Christmas.

In 1932, the Protestant church historian Hans Lietzmann expanded the thesis of his teacher Usener to the effect that Christmas was a prayer of thanks by the church for the victory of Emperor Constantine . This assumption would fit in with a transition from the cult of Sol to the cult of Christ in the personal and official religious practice of the emperor, to which parts of historical research in connection with the events of the year 313 have pointed. The fact that December 25th in Constantinople , the new royal seat of Constantine, was only accepted late, around 380, speaks against the religious-historical hypothesis in Lietzmann's version .

One difficulty in interpreting the history of religion is the assumption that there was a popular Roman holiday of Sol Invictus on December 25th, because the evidence for this is poor. An anonymous scholion from the 12th century was of great importance for Usener's argument ; He said that in the Orient there was knowledge of the background of the Christmas festival for centuries right up to the Middle Ages: "It is here admitted with surprising openness that Christmas was created according to the tried and tested principle of ecclesiastical policy to be a pagan festival that was dangerous for the Christian people. to replace the birthday of the sun god. "This text reads as follows in Usener's translation:

“The reason why the fathers changed the feast of January 6th (Epiphany) and moved it to December 25th was as follows. After a solemn custom, on December 25th, the heathen used to to celebrate the birth festival of the sun god (literally: the feast of the rising of the sun) and to light lights to increase the festivity. They also allowed the Christian people to participate in these festive customs. Since the teachers of the church made the perception that the Christians were attached to this (pagan) festival, after careful consideration they came to the decision that on this day (December 25th) from now on the festival of the true rising (i.e. birth) to celebrate the feast of the apparition (Epiphany) on January 6th. "

Steven Hijmans denies this basic assumption by Usener. It is based on anachronisms and assumptions of the 19th century about the Roman religion, which are historically obsolete. Usener had neglected the first part of the medieval Scholion, which makes it look like a neutral historical note. If you add this first part, according to Hijmans, the polemical context becomes clear: For the 12th century scholiast, the true feast of the birth of Christ on January 6th and its feast date on December 25th was a heresy.

Another difficulty in interpreting the history of religion is that Maximus of Turin makes the argument for December 25th as the date that there is no pagan parallel festival for this day . So pagan festivals like Sol invictus were n't too prominent.

Martin Wallraf suggests that Christian solar symbolism should not be seen as a takeover of Roman pagan solar symbolism, but rather as parallel phenomena that owed themselves to the same “zeitgeist”.

The question of the continuity between the Roman worship of Sol and the Christian cult also plays a certain role today in disputes about Christianity. For opponents of Christianity like Karlheinz Deschner , the fact that Christmas Day coincides with the feast day of Sol Invictus is an argument for assessing Christianity as syncretistic . Representatives of this position try to show that early post-Apostolic Christianity took over elements of older pagan religions and fused them with one another.

Further hypotheses

In 1921 Martin Persson Nilsson compared the Roman Saturnalia, which was celebrated from December 17th, in several respects (banquet, gifts, candles) with the modern Christmas festival. He did not mean, however, that the Christian Christmas feast of late antiquity goes back directly to the Saturnalia. "If, as is often claimed, something of our Christmas celebration comes from the S [aturnalien], it was conveyed through the Kalendenfest." The festival of the Kalendae Ianuariae , "favored by the court and zeitgeist", became more popular in the late imperial period. The Saturnalia remained under the name Brumalien until Byzantine times and was celebrated for a month from November 24th to the winter solstice on December 25th. The calendar festival lasted five days from January 1st (or the evening before December 31st) and was marked by New Year's gifts, a future show and masked parades. According to Nilsson, many Christmas and New Year customs are derived from the ancient calendar festival celebrated across the empire. These customs are referred to in Romance and Slavic languages with terms behind which the Latin word Kalendae can be recognized.

As an alternative to the hypothesis of the history of computation and the history of religion, Hans Förster suggests that the interest in a birth festival of Jesus Christ was related to the pilgrimages to the Holy Land, which took off in the 4th century. They were characterized by an effort to celebrate events described in the Bible in the right place at the right time. The annual service in the Bethlehem Church of the Nativity (January 6th) was therefore considered a model and was brought by the pilgrims to their home communities.

History of the Christmas party

Christmas celebrations were celebrated differently from region to region from the beginning; Over the centuries, they were based on different ideas of what constitutes the meaning, the essence of the birth of Jesus of Nazareth. It also depends on the current answer to this question whether you can certify that Christmas in the "Corona year" 2020 was a "normal Christmas", especially since the original meaning of the festival, especially since the 19th century, through expectations to a “successful festival” and customs were supplemented or superimposed, which at best have marginally to do with the birth of Jesus.

Expansion and upgrading of the church celebration

Christmas on December 25th came from the Latin west of the Roman Empire and only prevailed in the east against resistance. For the year 381, the celebration on December 25th by Gregor von Nazianz in Constantinople, who described himself as the initiator or sponsor of the Christmas festival in the capital. His sermons for Christmas and Epiphany were directed against Arian and Apollinarian teachings and emphasized the Trinitarian profession of Nicaea . Around the year 383, Gregory of Nyssa also celebrated Christmas on December 25th in Cappadocia. With the Christmas feast (referred to as θεοφάνεια, theopháneia “appearance of God”) Gregory commemorated the birth of Christ, while the Epiphany (called τὰ φῶτα, ta phôta “the lights”) - as in the Eastern Church to this day - was associated with baptism. In 386, John Chrysostom preached "with great rhetorical commitment" about the new Christmas festival introduced about ten years ago in the congregation of Antioch.

In Egypt, the Christmas festival on December 25th is only proven from 432 and was probably introduced in the dispute with Nestorius . In Jerusalem it was not celebrated until the 6th century under Justinian . While all other churches took over December 25th for Christmas, the Armenian Church holds on January 6th as the birth festival of Jesus.

As a day of remembrance of the birth of Christ, Christmas was initially classified in the calendar of the saints' feasts , although Leo the Great already referred to it as the Lord's Festival ( sacramentum nativitatis Domini ). The Sacramentarium Veronense (6th century) contains the oldest liturgical texts of Christmas, and the Sacramentarium Gelasianum testifies that Christmas in the 7th century changed from the calendar of remembrance days to the calendar of gentlemen's festivals (church year). From the middle of the 6th century there were three Christmas masses in the city of Rome due to special local conditions, and this custom was adopted in the Gallic-Franconian area in the early Middle Ages. Charlemagne made it binding in his empire. The midnight mass (already attested by Amalarius von Trier, † 850/53) reached a climax, the meaning of which corresponded to the Easter exultet : the festive recitation of the family tree of Jesus according to the first chapter of the Gospel of Matthew ( Liber generationis ) by a particularly talented singer, accompanied by bells, candles and incense.

In the High Middle Ages, Christmas customs emerged. Mystery plays in Christmas services are attested to be based on the example of the Easter plays in 11th century France. On the Day of the Innocent Children , the lower clergy had the opportunity to parody the higher; this since 11./12. Carnival traditions attested to in the 15th century were banned in the 15th century. Since the High and Late Middle Ages, Christmas came more and more under the influence of the Holy Virgin , although the liturgical texts remained unchanged.

Secularization and bourgeoisie

Until the end of the 18th century, Christmas was primarily a festival that took place in churches and on the streets (parade customs, Christmas markets ). Around 1800, different regional and confessional, a process began to use Christmas as an opportunity to strengthen family relationships. The private Christmas Eve ritual can be interpreted as a cultural performance (Milton Singer). "The parents act as game leaders, organizers and actors in their own production, whereas children and other guests act as audience and fellow actors at the same time." not the means for such a celebration and its props like the Christmas tree . Above all, a living room was required that had been prepared, was temporarily inaccessible to the children and was then ceremoniously entered with the use of lights, scents and music. Ingeborg Weber-Kellermann emphasizes that Christmas Eve only became a gift festival for children in the Biedermeier period . This gift relationship was one-sided, because gifts could not be given to the gifts brought by Santa Claus and Christkind, and at the same time as the family presents were presented, a variety of new toys came onto the market. The fact that intangible mythical figures are included in the family celebration as external bringers of gifts began more and more around 1840:

- The Christ Child probably goes back to the angels of the older Christmas parades. Martin Luther had suggested replacing Nicholas with the "Holy Christ". Starting from Protestant regions, the Christ Child spread as a gift-bringer in the 17th and 18th centuries in Catholic areas as well.

- In Santa Claus different male Schenk figures have been combined in the 19th century.

Exclusivity was not required, the Christ Child, Santa Claus, Nicholas and other characters ( Knecht Ruprecht , Pelzmärtel , Percht , etc.) appeared next to each other. Typically, the Christ Child remained invisible as a gift bringer. The Santa Claus role could be played by an outside adult (e.g. a family friend or a distant relative).

"German Christmas"

Jacob Grimm started the search for Germanic relics during Christmas. He had ideological reasons for this, according to Doris Foitzik : the establishment of a German national consciousness. In their German dictionary, the Brothers Grimm assumed the existence of a “midwinter festival lasting several days” of the pagan Germanic peoples, which they saw as evidenced in particular by Beda Venerabilis , who had written about Christmas: “The same night, which for us today is called the holiest of all, they named Pagans then with the name módra nect , d. H. Night of the mothers. ”The lexicographers then connected the resulting“ mother's night ”in a speculative way with the polytheistic cult of the matronae or matres . In the context of this festival, the Grimms also put the name Jul , which was inherited in parts of Germania, including the Low German region . From their point of view, both the adjective wîh used , which has hardly been adopted by Christianity, and the second part of the word approaching , which refers to the Teutonic counting of the days starting with the night, spoke in favor of a pre-Christian etymology . (The first evidence for the word Christmas comes from the 12th century, which speaks in favor of a Christian term. A loan translation of the Latin nox sancta from the prayers of the Latin Christmas mass using the vernacular vocabulary could be considered.)

It is rather unlikely that the origin of Christmas could be linked to a Germanic midwinter or Yule festival , since the birth festival already existed in the centers of the Christian world when the proselytizing of Central and Northern Europe was still imminent. It has been handed down that there were festivals for the North Germanic peoples in mid-winter. What is disputed, however, is at what time they took place and what their content was. The Icelandic monk Snorri Sturluson reports that Norway's first Christian king, Håkon the Good, had a festival called hoggunott or haukunott moved from mid-January to December 25th. This is sometimes interpreted to mean that the Christian king brought the usual midwinter invitation to his nobles forward to Christmas day; however, the text is not clear in this regard. Snorri also reports from a ritual sacrificial feast ("Jul drink") used by Odin , which took place regularly at Jul time.

From popular customs it was reconstructed that the old Germanic midwinter festival was both a death and fertility festival , at which the perchta , the matrons or mothers were sacrificed and masked young men as supposed ghosts of the dead spread horror and were supposed to revive nature by dancing ( see Perchtenlauf ). The Swedish festival of Lucia on December 13th originally fell on the day of the winter solstice , until the country switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar in 1752 . Typical solstice customs in southern Germany are also associated with the day of remembrance of St. Lucia of Syracuse (cf. the Lucien-Häuschen-Swimming in Fürstenfeldbruck in Upper Bavaria ). In the 19th century folklorists and theologians, especially in the German and Scandinavian countries, were very optimistic that they could prove that pagan customs continued to exist in the Christian Christmas festival. Today's research is much more cautious about this. Authors such as Carl Magnus Ekbohrn (1854), Alexander Tille (1893) and Gustav Bilfinger (1901) were convinced that the “ people ” had passed on their pagan customs over the centuries. With Tille it sounds like this:

“The Christian feast of the birth of Jesus and the Roman January calendar celebration… alone, however, do not make the essentials. The popular Christmas celebrations in Germany come mainly from the two great festivals of German autumn, which ... reach far back into prehistoric times. "

In 1878 Hugo Elm explained the “mysterious magic” of the “German Christmas” with the Nordic-pagan legacy, and in the late 19th century popular depictions of Germanic customs filled the Christmas editions of German daily newspapers.

The Franco-German War marked an intensification of the political instrumentalisation of Christmas. In the war winter of 1870, the army command had Christmas trees set up in hospitals and quarters everywhere. During the First World War , the “Christmas party in the field” was the highlight of the political staging at which the Kaiser gave a speech. The 1920s brought a new dimension to the politicization of the festival, both left and right groups used it for agitation. The song "Workers Silent Night" by Boleslaw Strzelewicz , which was banned by the censors several times in the German Empire, was very popular . The other side of the political spectrum developed July and solstice celebrations.

During the Nazi dictatorship, the pagan-Germanic aspects of Christmas were propagated through the mass media. While the Winter Relief Organization of the German People achieved a wide impact with gift campaigns (“Volksweihnachten”), it is difficult to estimate how popular Christmas decorations with rune and swastika motifs or Nazi Christmas carols were in family celebrations. According to Walter Hartinger, the Nazi interpretation of Christmas as a “central new pagan celebration of the dead and lights as a reminder of an allegedly urnordern Yule” was partially received in older literature about Christmas. In dealing with this ideology, the Roman Catholic Church took over the Christmas tree in the church, which until then had only been common in Protestant churches.

The complaint of consumer terror is typical of Christmas in the Federal Republic of Germany . Konrad Adenauer already expressed concerns in his Christmas address on December 25, 1955: “The exaggerated, the exaggerated of our time has admittedly affected the external form of our Christmas festival. It is with regret that one sees the exaggerated flood of lights in the streets and shops, which ... anticipates a large part of the joy in the glow of lights on Christmas Eve ”. For the New Left , the rituals of Christmas offered opportunities for parody and political action. Before the late Christmas Eve service on December 24, 1967, young SDS members tried to discuss the Vietnam War with visitors to the overcrowded Berlin Memorial Church . The action was drowned in the tumult; Rudi Dutschke climbed the pulpit planned or spontaneously, but was prevented from speaking and was beaten. After the demonstrators were forced to leave the church, the service continued as usual.

In contrast to the KPD of the Weimar Republic, which wanted to abolish the festival, a Christmas festival filled with new, secular content was worth preserving for the SED . Jolka-Tanne and Father Frost as socialist surrogates could be found on GDR Christmas markets as well as Christmas trees and Santa Claus. Christmas carols composed in the GDR combined the festival with the future vision of peace and social justice. Erich Weinert's Der neue Stern , a “proletarian Christmas carol” from 1929, which celebrated the red Soviet star as a new sign of hope and criticized Christianity , used Christian imagery at FDJ and FDGB Christmas celebrations in the 1950s :

“The poor see the light of heaven,

the rich are blind, they do not see it.

It shines everywhere on earth,

where poor children are born.

Because not one redeemer has arisen for us,

millions of redeemers in all lands. "

On the other hand, on Christmas 1961, GDR television broadcast Bach's Christmas Oratorio from the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig as a kind of national cultural asset. In the 1960s, traditional Christmas carols seemed unproblematic as they evoked nostalgic, but not really religious, feelings.

During the Cold War, Christmas provided an opportunity for competition between the two systems. The ritualized sending of Christmas parcels drew East and West Germans into a complicated relationship of mutual give and take, according to a study by Ina Dietzsch . The West German government wanted the content of the West Package to make clear to its recipients the advantages of the social market economy . "Candles in West German windows, Christmas trees on the inner-German border and Christmas carols that echoed over the wall were viewed in the GDR as a provocation and not as an expression of Christmas peace," says Doris Foitzik.

Anglo-American Christmas

In Geneva, after the Reformation was introduced in 1536, all non-biblical festivals, including Christmas, were banned. It was assumed that it was an originally pagan custom introduced by the papal church. John Calvin also took part in the discussions . Going further than Calvin, John Knox banned Christmas in Scotland in 1560. The Scottish Presbyterians followed this ban into the 20th century. Christmas in 16th century England was associated with banquets, alcohol consumption, dancing and gambling. The Puritanism therefore campaigned for the abolition of Christmas, which was in 1647 banned by Act of Parliament. This led to fights between friends and opponents of the festival. After 1660 compliance with the ban was no longer monitored. The strict observance of the Christmas ban was characteristic of Presbyterians and Quakers and was shown, for example, by the fact that they opened their shops on December 25th. In this context belongs the anti-Catholic polemic of Alexander Hislop , a pastor of the Presbyterian Free Church of Scotland . In his major work, published in 1858, Hislop claimed a Babylonian origin for several Catholic holidays, including Christmas. Customs of various religions, including the ancient Egyptian religion , Hinduism and the Anglo-Saxon religion, can be traced back to Babylon again and again for Hislop , where he also argued etymologically ( Jul is the Babylonian word for toddler, etc.).

In England, the puritanical position had an impact on society as a whole, so that it only became a popular festival in the 19th century. The impetus for this came from the British royal family ( Prince Albert came from Germany).

The New England states, dominated by Puritans, Presbyterians, Quakers, and Mennonites , did not celebrate Christmas until the 19th century. A Christmas ban in Massachusetts had to be lifted again in 1681 under pressure from the English government. The Unitarians living in New England refused to celebrate Christmas until the 19th century.

Poets with a free church background made a significant contribution to the English-language Advent and Christmas carols (examples: Hark! The Herald Angels Sing by Charles Wesley and Joy to the World by Isaac Watts ). In addition to the songs, another aspect for the acceptance of Christmas in the reformed and free church area became important: In view of the social hardship of the 19th century, the "Festival of Love" offered an opportunity to practice Christian charity. This is particularly evident in the case of the Salvation Army . Their trombone choirs and collecting campaigns have been part of the stereotypical image of American Christmas since the late 19th century . A spectacular action by the Salvation Army was the Christmas dinner for 20,000 people in Madison Square Garden in 1899 .

At the beginning of the 19th century, there was a desire among upper-class circles in the city of New York, which had been founded by the Dutch as Nieuw Amsterdam in 1624, to create traditions for a young city. A Dutch New York Christmas party was reinvented, supplemented by a "traditional" British Christmas party. The result was a nostalgic, quiet domestic celebration with a focus on giving presents for children. It became popular through the writings of John Pintard , Washington Irving and Clement Clarke Moore , among whom are Charles Dickens and Harriet Martineau as European authors .

- John Pintard promoted the character of Sinterklaas in New York , who came across the Atlantic and brought pastries from Amsterdam that he distributed to good children.

- Washington Irving ( History of New York , 1809) made this alleged New York tradition known nationwide.

- In 1823 an anonymous poem An Account of a Visit of St Nicholas appeared in The Sentinel in Troy, New York . It changed the appearance of Santa Claus into a kind gift bringer who was traveling on a flying reindeer sleigh. If the date of the present was on St. Nicholas Day or New Year, Santa Claus has been associated with December 25th since this poem. Clement Clarke Moore stated in 1844 that he was the author of the poem, but possibly wrongly. Linguistic evidence points to Henry Livingston, who died in 1828 and who wrote occasional poems for newspapers.

On June 26, 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant declared Christmas a national holiday in America; In 1923, First Lady Grace Coolidge lit the candles on a National Christmas Tree that has been common since then . The separation of church and state in the United States is expressed in the fact that the US Postal Service issues two Christmas stamps annually , so that you can choose between a secular motif and a Christmas painting from the National Gallery of Art .

Christmas as a globalized festival

While Christmas in the Christian context mostly globalized peacefully and in the non-Christian context either certain customs were loosely adopted, as in East Asia, or Christian and non-Christian things were combined, as is not uncommon in Judaism and Hinduism, it certainly does exist, especially in the Islamic world fierce resistance to Christmas, including bans and terrorist attacks on churches and the like.

In Christian countries

In the 19th century, regional Christmas customs were first propagated nationwide, parallel to national identity-finding processes, in the 20th century Christmas was then globalized as a result of trade, migration and colonialism . For example, A Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols , originally (after 1918) a celebration of King's College (Cambridge) , became internationally known through radio and television. The US troops stationed in many countries after the Second World War contributed to the spread of American Christmas culture , which is particularly evident in Japan.

Santa Claus, the epitome of American Christmas culture, has been the target of aggressive protests on several occasions. In 1951, a Santa figure was publicly burned in front of Dijon Cathedral after 250 children sentenced him to death as a liar. Two Roman Catholic clerics chaired this event. The action became known through the report by Claude Lévi-Strauss .

There have been several short-lived attempts to replace Santa Claus with a national gift-bringing figure in Latin America, including Volvo Indio in Brazil, Quetzalcóatl in Mexico, and Don Feliciano in Cuba.

In China

In China, Christmas is not a family celebration (in contrast to the traditional New Year celebration ), but a time for joint activities with friends and colleagues. The elaborate Christmas decorations in public spaces in Chinese cities represent modernity.

In Japan

Today's Japanese Christmas ( Kurisumasu ) is an evening that couples spend together, so love and romance are thematized in advertising.

In Judaism

The Jewish Hanukkah festival, like Christmas, takes place in December, and the lighting of candles traditionally plays an important role in both festivals. However, there are no similarities with regard to the festival occasion: The Hanukkah festival commemorates the rededication of the Jerusalem temple in 164 BC. Chr., On the other hand, Christmas celebrates the birth of Jesus. Since the Enlightenment there has been a tendency in Judaism to celebrate Christmas as a cultural festival of the majority society by combining it with elements of Hanukkah. This response to the so-called "December dilemma" is in the German language " Chrismukkah called" the Anglo-American "Chrismukkah". Other options include upgrading the Hanukkah festival so that Hanukkah symbols are present in public spaces, and offering alternative programs on December 25 in Jewish community centers and museums.

In Hinduism

For Hindus who live in Christian states or areas, a connection between the Divali Festival of Lights in late autumn and Christmas is obvious. The festive illumination remains in many Hindu temples in Europe and North America through Christmas through early January.

In India, the right-wing party Vishwa Hindu Parishad is opposed to supposed Christian missions in the context of Christmas. In 2014, for example, she condemned a performance by Santa Claus in a Christian school in Chhattisgarh because the sweets that were distributed were a bribe to convert Hindus to Christianity.

In Islamic states

While elaborate Christmas decorations can often be seen in more secular Islamic countries with a Christian minority , such as the Christians in Syria , Christmas and the traditions associated with it are fiercely opposed or even banned in a number of Islamic countries.

In December 2015, Christmas was banned in Somalia on the grounds that it was a Muslim country that would not tolerate non-Islamic festivals. Also in 2015, the government of Brunei banned Christmas decorations and the singing of Christmas carols, as well as all other Christian customs for locals, as the festival endangered the Muslim faith. The government of Tajikistan banned Christmas trees, fireworks, banquets and gifts on the "Festival of Love". Sharia law applies in the Indonesian province of Aceh . Local Islamic clergymen demand that Christmas should not be visible in public space so that Muslims do not come into contact with it.

In Islamic states, churches belonging to the Christian minority have been the target of terrorist attacks with an Islamist background on several occasions at Christmas: in 2010 and 2017 in Egypt and in 2013 in Baghdad , Iraq . In Tajikistan, a man disguised as Father Frost was lynched by an Islamist mob in 2012. See also: Terrorist attacks on Easter Sunday 2019 in Sri Lanka .

In Africa-centered culture

Kwanzaa , originally an African harvest festival that was established in the United States in 1966 as an Afro-American holiday, is celebrated at the end of December and, like divali, can be associated with Christmas.

Liturgy and Customs Today

The Christmas season in the church year

The Christmas festival circle consists of the Advent season and the Christmas season. After the last Sunday of the church year, the new church year begins on the first Sunday in Advent .

The Christmas feast begins liturgically with the first Vespers of Christmas on Christmas Eve (see also Christvesper ). The first liturgical highlight of the Christmas season is midnight mass on the night of December 24th to 25th (see Christmas mass ). The eighth day or the octave day of Christmas is also known as Ebony Christmas in the Alpine region .

The Christmas season ends in the Protestant churches with Epiphany (apparition of the Lord) on January 6th, in the ordinary form of the Roman rite of the Catholic Church with the feast of the baptism of the Lord on the Sunday after the apparition of the Lord . In the Old Catholic Church and the extraordinary form of the Roman rite, the Christmas season ends with the rite of the closing of the nativity scene on the feast of the Presentation of the Lord on February 2nd, popularly known as Candlemas or Candlemas .

Deviating from this custom, which is valid in many Western churches , the Ambrosian rite , which is mainly cultivated in the diocese of Milan, has also retained the regulations of Ambrose in the liturgical reform of the Roman Catholic Church . There the Advent season begins on November 11th , a quarter day , which results in six instead of four Advent Sundays, and the Christmas season ends on February 2nd with the feast of the Presentation of the Lord (also popularly called Candlemas). The tradition has thus been preserved there that times of penance and fasting as well as the Christmas and Easter times of joy based on Jesus' retreat into the desert (40 days; Mt 4,2 EU ), the Flood (40 days; Gen 7,4.12 EU ), Noah's Waiting in the Ark on Mount Ararat (40 days; Gen 8,6 EU ), Israel's Exodus (40 years; Ex 16,35 EU ) each last 40 days. In customs, the differences can be seen in the fact that the Christmas tree and nativity scene remain in place until January 6th or February 2nd.

At the feast of the Presentation of the Lord , the Christmas season reverberates. This can be seen, among other things, in the liturgical pericopes of the day, which are the same in Western churches. In the Old Testament reading ( Mal 3,1–4 EU ) the Advent season echoes , the epistle (Protestant Heb 2,14–18 LUT , Catholic Heb 2,11–12.13c – 18 EU ) already looks at Good Friday , the Gospel (Evangelical Lk 2.22–24 (25–35) LUT , Catholic Lk 2.22–40 EU ) directly follows on from the Christmas Gospel .

Roman Catholic

Gregory the Great was already familiar with three holy masses on Christmas. The titular churches of Rome, on the other hand, initially only celebrated two holy masses: one night in connection with Matins and the high mass on the following day. The Capitulare lectionum from the middle of the 6th century already contains the classic sequence of readings from the prophet Isaiah , from the Pauline letters and the gospel for all three Christmas masses . This order was common well into the Middle Ages, locally until the 18th century.

The oldest of these masses is the festive mass “am Tage” ( Latin in die ) , which is already mentioned by Ambrosius and Pope Celestine I at the beginning of the 5th century. The station church was St. Peter in the Vatican , and since the 12th century Santa Maria Maggiore . The second mass was a midnight mass probably taken over from Jerusalem ( in nocte "in the night", popularly called Christmas mass because of the connection with Matutin , also "angel office", because the gospel with the singing of angels at the birth of Jesus ( Lk 2, 13f EU ) closes). The station church of the midnight mass was the Marienbasilika on the Esquilin , ( S. Maria Maggiore ). The day mass was moved there in the 11th century, because the church houses a replica of the nativity grotto in the crypt . A third mass came at dawn ( mane in aurora , “early at dawn”, popularly called “pastoral mass” or “pastoral office” due to the gospel of the adoration of the shepherds) in the Byzantine court church of Santa Anastasia on the Palatine Hill - “possibly out of courtesy to others [Byzantine] officials residing there ”- added. The patronage of St. Anastasia was celebrated there on December 25th . This papal station liturgy led to three masses with different measurement forms being celebrated on the same day. The texts are from Gregory the Great. So the Christmas liturgy as a whole came to the Gallic-Franconian north. Charlemagne then declared it binding.

In the 11th century, scenic representations in church services, so-called Christmas games, appeared for the first time in France. Francis of Assisi set up a manger with a live ox and donkey in Greccio , read the Gospel during mass and gave a sermon. In the Habsburg lands, Emperor Joseph II banned the nativity plays during mass, which therefore became a domestic custom .

Liturgically, the Christmas season begins with the first Vespers of the birth of Christ on December 24th and ends with the feast of Christ's baptism on the first Sunday after Epiphany . The reading texts progress in the masses. In the mass on Christmas Eve the expectation is still in the foreground ( Isa 62,1–5 EU ; Acts 13,16–26 EU and Mt 1,1–25 EU ). Joy is expressed in Christmas mass ( Isa 9,1–6 EU ; Tit 2,11–14 EU and Lk 2,1–14 EU ; Oration Deus, qui hanc sacratissimam noctem ). The Christmas Mass in the morning is about the hope of salvation through the Incarnation ( Isaiah 62,11 f. EU , Tit 3.4 to 7 EU and Lk 2.15 to 20 EU ). The subject of high mass or the daily mass is God's plan of salvation, as it is expressed in the prologue of the Gospel of John John 1 : 1–18 EU ; previous readings are Isa 52.7-10 EU and Hebrew 1.16 EU .

The feast of Christmas received an octave in the liturgy from the 8th century , in which, however, the saints feasts that fell during this time and that already existed at the time were retained. They are the festivals ofComites Christi ( lat. "Companion of Christ"), namely of Stephen (December 26th), John the Evangelist (December 27th) and the innocent children (December 28th). Since 1970, the Roman Catholic Church has been celebrating Octave Day ( New Year ) as the solemn feast of Mary, the Mother of God. Until 1969, the feast of the Lord's circumcision was celebratedon the day of the octave of Christmas.

In the church year are on the date of Christmas, the feast of the ordained Annunciation on March 25, nine months before Christmas, and the feast of the birth of John the Baptist on June 24, six months before Christmas so that is the dating of Luke 1 , 26 EU , according to which Mary became pregnant with Jesus “in the sixth month” of her relative Elisabeth's pregnancy. Even the St. Martin on November 11, is related to Christmas on this day began in the Middle Ages, the original six-week Lent in preparation for Christmas, the Advent was limited later to four weeks.

Evangelical

In the German-speaking Protestant churches, as in the other western churches, Christmas begins on December 24th at sunset. Christmas Vespers is celebrated in the late afternoon or early evening, and Christmas Eve at night .

Psalm 96 plays a major role in church services . Since the reorganization of the pericope order on the 1st of Advent 2018, the following reading order applies to the Christmas services:

| Christmas Vespers | Christmas Eve | Christmas festival - 1st holiday |

Christmas festival - 2nd holiday |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Testament reading | Isa 9 : 1-6 LUT | Zechariah 2 : 14-17 LUT | Isaiah 52: 7-10 LUT | Isaiah 7: 10-14 LUT |

| epistle | Gal 4,4-7 LUT | 1 Timothy 3,16 LUT | Titus 3, 4-7 LUT | Hebrews 1 : 1-4 (5-14) LUT |

| Gospel | Lk 2,1-20 LUT | Luke 2,1-20 LUT | John 1,1-5.9-14 (16-18) LUT | Matthew 1,18-25 LUT |

In order to prevent "nocturnal mischief", the Christmas mass, which is the focus of Christmas, was moved to the earliest morning of the festival day (often at 4 o'clock) or it was replaced by the evening vespers. The official reserves against the midnight service led to conflicts until the 18th century. The number of congregations in which the night service ( Christmas Eve ) is held today is increasing again. The evangelical church service book from 1999 included a separate form for this. A special feature of the Protestant Christmas festival, which goes back to the time of the Reformation, is to extend the Christmas festival to the second (previously even the third) day of Christmas. Many church ordinances stipulated that the birth of Jesus should also be preached on the second holiday. The Protestant Service Book offers two forms for this, "Christfest I" and "Christfest II", which are, however, interchangeable. The feast of the arch martyr Stephen can be considered in an evening service. New Year's Day can also be celebrated as the day of the circumcision and naming of Jesus .

American Lutherans, Episcopalian, and Methodists use the Common Lectionary produced by the Consultation on Common Texts . Then the following texts are used: Isa 9 LUT , Tit 2 LUT , Lk 2,1–20 LUT or: Isa 52 LUT , Hebr 1 LUT and Joh 1,1–14 LUT or: Isa 62 LUT , Tit 3 LUT and Lk 2 , 1-20 LUT . For active Anglican parishioners , communion is the climax of the midnight Eucharist. While the earlier Book of Common Prayer on Christmas Eve only referred to Christmas in a few prayers, in today's common agendas, such as Common Worship from 2000, the Christmas event is placed at the center of scripture reading and prayers.

The Reformed Church prefers the principle of reading the path ( lectio continua ) over a pericope order. In the Agende Reformierte Liturgie , which was drawn up on behalf of the Moderame of the Reformed Covenant , it says:

“It has always been a matter of course for the Reformed congregations and churches to celebrate the great solemn festivals of Christianity. The Advent and Passion times also had a shaping effect. A strict observation of the annual cycle, connected with it the reading and pericope order, did not take place. [...] The Reformed forms of worship do not have a fixed proprium. "

The liturgical calendar valid in the United and Lutheran churches of Germany is appended to this reformed agenda. Each Sunday and holiday is assigned a question from the Heidelberg Catechism . The following texts were selected for Christmas:

- Christ Vespers and Christmas Eve: Question 29 ( Why is the Son of God Jesus, that is, "Savior" called? )

- Christmas, 1st holiday: Question 33 ( Why is Jesus Christ called "God's only begotten Son", since we too are children of God? )

- Christmas, 2nd holiday: Question 36 ( What use is it to you that he was conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary? )

Orthodox

The Eastern churches have always focused on theophany , today epiphany , on January 6th. It's older than Christmas. The sermons of Gregory of Nazianz from the years 380 and 381 mark the transition from the overall festival of Epiphany to the two festivals of Christmas - with the focus on the birth including the adoration of the wise men - and Epiphany, which is now exclusively related to the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan. Antioch took over Christmas a short time later, as evidenced by a sermon by John Chrysostom from the year 386. The Jerusalem Church rejected Christmas until the 6th century.

In the other Orthodox churches, Christmas is celebrated on December 25th, but there are differences due to the different handling of Pope Gregory's calendar reform from 1582, which was only adopted in the Catholic, then also by the Protestant churches would. Only the New Julian calendar developed by the Serbian mathematician Milutin Milanković in 1923 made it possible to partially align the fixed dates in East and West. The Orthodox faith communities are still divided on this issue. The Orthodox churches of Constantinople (the Ecumenical Patriarchate ), Alexandria , Antioch , Romania , Bulgaria , Cyprus , Greece (with the exception of the monasteries ) have had the New Julian calendar - which, like the Gregorian calendar, is supposed to correct the inaccuracy of the old Julian calendar Mount Athos), Albania and the Syrian Orthodox Church . The Orthodox Church of Finland had already adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1921. Other old calendar- oriented local churches still adhere to the Julian calendar for all church holidays, including the Russian , Belarusian , Ukrainian , Serbian , New Macedonian , Georgian and Jerusalemite Churches as well as the Autonomous Monastic Republic of the Holy Mountain . They celebrate all fixed holidays in the period from 1900 to 2100 13 days later than the western churches and the Orthodox new calendars . They therefore celebrate Christmas on January 7th of the Gregorian calendar.

The pre-Christmas fast , which is less strict than the fast before Easter, since fish can be consumed, and among the Orthodox begins 40 days before Christmas. It gets stricter from December 17th and peaks on December 24th. However, this is not a liturgical Advent season . During this time, the liturgy is gradually enriched with Christmas motifs. The last two Sundays before Christmas are dedicated to the ancestors of Christ. On December 24th, Vespers is celebrated with eight readings of scriptures, all of which point to Jesus as the fulfillment of the prophecies. Vespers is followed by the baptismal liturgy of Basilius , a reference to the sentence: “You are my son, today I have begotten you” Ps 2,7 EU . The readings consist of Heb 1,1–12 EU and Lk 2,1–20 EU . The great Compline goes into the morning service. Both together are considered to be the “night watch” in which the birth of Christ is proclaimed according to Mt 1.18-25 EU . At Matutin the entire canon Christ is Born is sung, and the believers pray in front of the icon of the birth of Jesus.

The liturgy of Christmas Day deals with the magical visits and emphasizes the reign of Christ. The Chrysostom anaphora is used for this. The Gospel from Mt 2, 1–12 EU is dedicated to the visit of the magicians. With the second Christmas holiday, the six-day Nachfeier starts Synaxis the Theotókos ( gr. Σύναξις , Θεοτόκος ) (synopsis of Theotokos ), a read of devotion to Mary . On January 1st, Orthodoxy celebrates the solemnity of the Lord's circumcision .

Armenian

The Armenian Apostolic Church adheres to the comprehensive festival date of January 6th. Since the Julian calendar is still used in this church, this festival falls on January 19th according to the Gregorian calendar.

Role of the state

Holiday regulations

The word "celebrate" also has the meaning: "let work rest". In this sense, the statement of the Spanish King Philip II is to be understood, who says to the Marquis von Posa in Friedrich Schiller's drama Don Carlos (II / 10) : "When such heads celebrate / How much loss for my state". Public holidays are days on which the state concerned orders that work be largely suspended in its territory. The time off for the majority of people in the country concerned enables them to take part in traditional celebrations, but does not oblige them to do so in democratic states.

Christmas holidays are public holidays in December or January in countries with a culture that is (also) influenced by Christianity. The number of public holidays is determined differently depending on the country.

Behavioral expectations

In Finland and Estonia , “ Christmas Peace ” is proclaimed on Christmas Eve . In the past, people who committed an offense during the Christmas truce in Finland received twice the usual penalty. The idea that negative behavior practiced at Christmas is particularly morally reprehensible is also widespread outside Finland and Estonia. However, in states that are committed to ideological neutrality, it is not permissible to make the amount of penalties dependent solely on the time of the offense.

economic aspects

In the literature there is also criticism of Christmas in its current form, which is "contaminated" by non-religious motifs and manifestations. The criticism can essentially be concentrated on the key words profanation , commercialization as well as hectic rush and stress.

From the point of view of profanation , the main argument is that Christmas has become de-Christianized and has become a family festival for everyone. The theological content is largely lost, instead kitsch and sentimentality are increasing.

The time of the Christmas business (i.e. the time of sales from the week before the 1st Advent) is the time of the year with the highest sales in retail. With regard to commercialization , the increase in sales with Christmas motifs in department stores and advertising, which goes back to the Advent season and often beyond, is lamented. The traditional term “ Advent season ” is tending to be replaced by the term “pre-Christmas season”, the beginning of which is not clearly defined. The "pre-Christmas season" now often opens at the end of August or beginning of September with the sale of traditional Christmas cookies such as speculoos, wafer gingerbread, stollen and dominoes. The medium-sized trading company Käthe Wohlfahrt has been trading Christmas items all year round in several cities in Germany and some neighboring countries as well as in the United States for over 50 years.

Cultural aspects

iconography

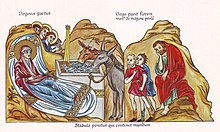

The Christian iconography developed their motives initially from the accounts of Matthew and Luke, and from the apocryphal infancy gospels. There were also many legends from various origins. From the representations in the catacombs in the 3rd century until well into the Renaissance , the birth scene was associated with the Annunciation to the Shepherds and the Adoration of the Magi. The stable was added in the 4th century. Very early on, the pictures address the special relationship between Jesus and Mary , for example the first bath or the mother breastfeeding the baby Jesus , with a star above Mary ( Domitilla and Priscilla catacombs , late 3rd century). The earliest artistic representation of the birth of Jesus Christ comes from the time around 320. There the crib is adapted to the shape of an altar .

The discovery of the Nativity Grotto by St. Helena and the building of the Church of the Nativity by Emperor Constantine led to a new topic . The ox and donkey have been in the pictures that refer to Isaiah 1,3: "The ox knows its owner, the donkey its manger" since the early 4th century . You and the magicians in the same picture mean that both the highest and the lowest living beings worship the child. The ox as a pure animal also symbolized the Jewish people, who are bound by the law, the donkey, as an unclean animal, symbolized the pagan peoples under the burden of paganism. There are only pictorial representations with the child in the manger and the two animals; The indispensability of ox and donkey is interpreted in the sense of Logos theology as an indication of the arrival of the Logos in the world of the Aloga, the Logos-less.

The Byzantine depictions also depict the two midwives Zelomi and Salome, who are supposed to emphasize the real human birth of Jesus in the Christological debate of the time. Salome, who doubts the virgin birth of Jesus, wants to examine this fact with her hand, which then withers as a punishment. The touch of the boy Jesus heals them again. This theme is a popular motif in Eastern art in the 5th and 6th centuries and is depicted on the left front ciborium column of St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, which was stolen from Constantinople.

The genre of Biblia pauperum (" Poor's Bible ") has a number of allusions in its references:

- According to the image of the root of Jesse ( Dan 2.45 LUT ), Mary is the uncut mountain, the birth cave is her womb. “A stone broke loose without human intervention.” Christmas is related to Easter . The cave is also a symbol of his grave. The church father Irenaeus compared the incarnation of Christ with his journey into hell between death and resurrection.

- The burning bush Ex 3 EU is considered to be the prefiguration of the virginity of Mary . Just as the flame did not consume the thorn, so conception did not harm virginity. Walter Felicetti-Liebenfels describes an icon in the Sinai monastery from the 14th century, on which Mary herself is placed in the burning bush. Even the verdant Aaron rod ( Num 17,23 EU ) stands for the virginity because Aaron Staff wore flowers, without having been planted.

- The depiction of Gideon with the fleece Ri 6.37 EU was the sign of Gideon's vocation to save his people and symbolized the work of the Holy Spirit on Mary. Even Ezekiel outside the locked gate Hes 44.2 EU is a symbol of Mary's virginity.

These four prefigurations were developed in Byzantine art as early as the 9th century and later also came to the West. They can be found on panel paintings from the 15th century, where they are grouped around the depiction of the birth of Christ, for example on the central panel of the winged altar in the Sam monastery.

The ancient iconography of the mystery cults, which also knew the birth of a god, had an influence on the early Christian depictions, as certain parallels to ancient depictions of the birth of Alexander or Dionysus show. The midwife Salome Maria shows her withered hand on an ivory relief from around 550. The posture of Mary, lying, half upright with the left hand on the chin, is very similar to the half-lying and half-seated Semele at the birth of Dionysus on an ivory pyxis in Bologna.