Aeon (philosophy)

Aeon or Aion (from Greek ὁ αἰών , ho aiṓn , from archaic Greek ὁ αἰϝών, ho aiwṓn ) is a term used in ancient and late ancient philosophy and religion, which originally referred to world time or eternity , later a deity in which it was hypostatized . These eons do not mean 'periods of time' (see, inter alia, eons in theology ), but beings or, in summary, the emanations of a 'supreme deity' ( gnosis ).

Greek literature and philosophy

The Greek term aiṓn denotes the individual “life” or “lifetime”, then also a “very long, unlimited time”, an “age” or “eternity”. In the medical context, aiṓn was a name for the spinal cord as the seat of life force. In Greek philosophy, Aion first appears in Heraclitus' doctrine of Logos :

"Aion is a boy who plays, puts the board back and forth: a boy owns the kingdom."

The game here may mean the succession of cyclical periods of time (days, seasons, ages), which is regulated by an eternal god of time: the game ends, the stones are set up again and a new cycle begins. Euripides introduces Aion as the son of Chronos .

In Plato , the aion appears as the ideal counter-concept to the empirical, cyclically advancing time, which Plato describes as the god Chronos . The sky with the cycles of movement of the celestial bodies and spheres is a symbol of eternity, but not eternity (Aion) itself. For the Neoplatonists , Aion consequently becomes the term for the order and time of the universe.

For Aristotle the Aion is described as follows:

“The telos (the biological as well as spiritual perfection and final stage), which includes the lifetime of each individual, is called aion (eternity). In the same way, however, the telos of all heaven (with the stars) Aion, a word that is formed from aeí (ἀεί, "eternal"), is immortal and divine. "

The late antique poet Nonnos von Panopolis depicts the god Aion as a decrepit old man and advisor to Zeus, who rolls the wheel of time and rejuvenates himself again and again, and who is said to have played a role in the birth of Aphrodite. Further mentions of this poetic-mythological figure can be found in Quintus of Smyrna , Synesios of Cyrene and the Nonnos student John of Gaza.

Aion as deity in ancient syncretism

Attempts have been made relations between the idea of Aion in Plato and Aristotle to Iranian manufacture sources, in particular to Zurvan , the personification of the Creator God of time and eternity in zurvanistischen special form of Zoroastrianism .

The worship of a deity Aion can only be proven in Roman times. A single inscription found in Eleusis ( SIG 1125) with a dedication to Aion, which presumably dates from the time of Augustus , cannot yet be taken as evidence of any widespread worship of Aion as a deity. The fact that Aion appears in the context of the Roman imperial cult (e.g. on the front relief of the column of Antoninus Pius , where the winged Aion with snake and globe in his left hand portrays the deified imperial couple Antoninus Pius and Faustina ) cannot be any clear evidence for either worship, as it could also be a purely allegorical figure. (In ancient religion, trying to distinguish between allegorical figure, hypostasis , numen and deity is of course difficult, perhaps pointless.)

Whatever the connection between the Zoroastrian god Zurvan and Aion , it is obvious that the portrayal of Zurvan (traditionally as a winged human figure with a lion's head, around whose feet a serpent winds) had an effect on the Aion iconography . Corresponding images have often been found in Mithraea . However, a distinction from the representations from the Orphism derived Phanes , which is also often shown together with a snake difficult. In the context of the Mithras cult, there are often portraits in which Aion is shown as a young man standing in a zodiac , for example on the mosaic from a Roman villa near Sentinum (near today's Sassoferrato in Umbria ) shown in the Munich Glyptothek .

At the end of the 4th century, Epiphanius of Salamis reports that during his time in Alexandria the feast of the birth of Aion was celebrated by the virgin Kore on the night of January 5th to 6th . This birth took place in an underground shrine in the Koreion , the temple of the Kore. There was a wooden image of Aion which, after hymns had been sung all night long, was adorned with five golden crosses at dawn and carried around in procession. This statue is also mentioned in the Suda , and it is implied that the actual name of the god is secret. The parallels to the Christian Feast of Epiphany are obvious and were already noticed in antiquity. Hermann Usener even assumed the Christian renewal of a pagan cult. But the feast of Aion also has connections to other deities - as Epiphanius already suggests - namely through the drawing of the Nile water for the feast of the discovery ( heúresis ) of Osiris , and through the date for the feast of the Epiphany of Dionysus .

The term "aeon" in Gnosis

Gnosis (from ancient Greek γνῶσις gnō̂sis "[knowledge]") or Gnosticism (Latinized form of the Greek γνωστικισμός gnōstikismós ) denotes various religious groups as syncretistic teachings, the high point of their formulation in the 2nd and 3rd centuries after Had Christ. The various Gnostic systems also point to earlier (ancient) precursors.

Ancient religious and philosophical systems are fundamentally committed to describing the initial reasons. Thinking about origins is elementary, there must be no beginning without an origin. The origin and the unity of beings are to be named in order to grasp the essence and goal of the world and of life. In Gnostic cosmogony , a dualistic worldview is assumed that separates a material world from a heavenly world of light. There is a spark of heavenly light in the soul of man; it is trapped in the body of man on earth. The knowledge, γνῶσις (gnō̂sis) gives the way to redemption, it is the memory of one's own (heavenly) origin from the light. While the material world or creation of the demiurge is filled with "loneliness", with "terrible fear" of demonic powers. All real life activities are "toxic and demonically infected".

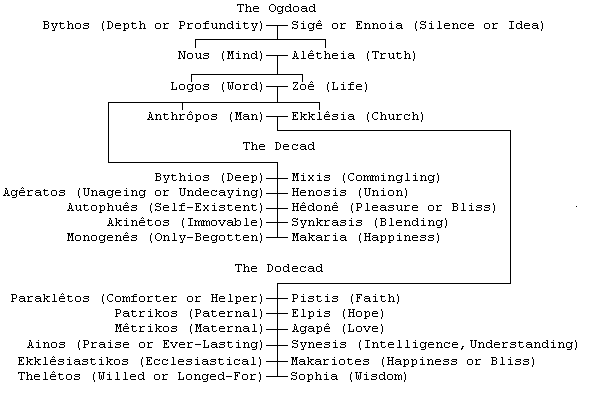

In most of the Gnostic systems and narrations , the various emanations of the supreme deities were collectively referred to as aeons, the totality of all aeons, their number differed greatly between the various groups, and they all formed the pléroma. The aeons, together with their divine origin, the “unknown god”, form the Pléroma ( ancient Greek πλήρωμα “fullness” ), the sum of the purely spiritual beings. The "unknown God", who eludes all human imagination, is surrounded by a fullness, the Pléroma of spiritual beings or spirit beings, the aeons that he emanates from his unfathomable source. Often the eons emanated from the deity appear as male-female pairs or dualities , συζυγίαι syzygies . Eons are sequences of beings, 'spirit beings', that is, a first eon or a pair of eons works and what it is able to work affects the next dual pair. Then it is replaced by another and this, after it has worked with its powers, is in turn replaced by a further pair of eons and so on.

According to von Ostheim (2013), they are comparable to 'essential platonic ideas '. But they also show correspondences to the angelic hierarchies of the Jewish and Christian tradition.

The Gnostic systems mostly assume a highest, 'divine consciousness'. Such a 'divine principle' has nothing to do with the creation of the world, the physical, real world. Rather, a whole series of deities are postulated, which are located between the 'highest spirit being' and the physical-real world. It is the eons, the 'divine intermediate beings', which emerged from the highest as emanations and developed in a descending tendency, mostly dual. The further they move away from the metaphorical 'divine source of light', the weaker their 'light' is. The last eons would become the 'evil deity'. This evil eon would be the 'Creator God' ( Demiurge ). His striving leads to the visible, he created the world with its matter and thus also the body for the human spirit. The 'human mind' is seen as an effluvium from the 'aeon world of light'. The human mind would be enclosed and imprisoned by the body that the Demiurge created. Through knowledge, knowledge and insight, man can become aware of the divine origin of his spirit and try to free his spirit from the 'prison of the body'. The good divine spark in man, his divine core, can only be redeemed through liberation from the evil body, the work of the demiurge.

literature

- Heinrich Junker: About Iranian sources of the Hellenistic Aion concept. In: Lectures of the Warburg Library , Vol. 1. Teubner, Leipzig 1921, pp. 125–178.

- Doro Levi : Aion. In: Hesperia 13 (1944), pp. 269-314.

- Wolfgang Fauth : Aion In: Little Pauly. Alfred Druckermüller, Stuttgart 1964. Vol. 1, Col. 185-188.

- Günther Zuntz : Aion, god of the Roman Empire. Presented on November 12, 1988. (= Treatises of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences . Philosophical-historical class 1989.2). Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1989.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ See e.g. B. Homeric Hymn to Hermes 42.

- ↑ DK Heraklit B 52. Heraklit takes up a Homeric parable here.

- ↑ Euripides, Heraclids 898 ff.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus 37d.

- ^ Aristotle, De caelo I, 9, quoted from RGG , Vol. 1, p. 194.

- ^ Nonnos of Panopolis, Dionysiaka VII, 22 ff .; XXIV, 265 ff .; XXXVI, 422 f .; XLI, 178 ff.

- ^ Quintus of Smyrna, Posthomerica XII, 194 f.

- ↑ Synesios of Cyrene, Hymns 9:67.

- ↑ John of Gaza, Tabula mundi I, 137.

- ↑ Epiphanius von Salamis, Adversus haereses LI, 22, 8 ff.

- ↑ See Suda On Line , sv "Ἐπιφάνιος" ( epsilon, 2744 ) and "Διαγνώμων" ( delta, 522 ).

- ↑ Hermann Usener: The Christmas Festival (= religious history studies , first part). Friedrich Cohen, Bonn 2 1911, p. 27 ff.

- ↑ Jarl Fossum: The Myth of the Eternal Rebirth. Critical Notes on GW Bowersock , "Hellenism in Late Antiquity". In: Vigiliae Christianae , Vol. 53, No. 3 (August 1999), pp. 305-315.

- ↑ Udo Schnelle : The Gospel according to John. Theological hand commentary on the New Testament. 5th edition, Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2016, ISBN 978-3-374-04317-0 , p. 41

- ↑ Martin R. von Ostheim : Self-redemption through knowledge. The Gnosis in the 2nd Century AD Schwabe, Basel 2013, ISBN 978-3-7965-2894-1 , pp. 74–75

- ↑ George Robert Stow Mead , Helena Petrovna Blavatsky : Pistis Sophia. Lucifer 6 (1890) (33): 230-239. London: The Theosophical Publishing Society.

- ↑ Compare also Epiphanios of Salamis : Adversus haereses. I 31.5-6