Valentinus

Valentinus ( ancient Greek Βαλεντίνος Valentinos , German also Valentin , rarely Valentinian or Valentius Gnosticus ; * probably around 100 AD ; † after 160 AD ) was a Christian Gnostic teacher. He is considered the founder of the "Valentine Gnosis", the followers of his teachings are called Valentinians.

Life

Little is known about the life of Valentinus. He lived around the middle of the 2nd century. According to a tradition reproduced with reservation by Epiphanius of Salamis , he was born in Phrenobis not far from Alexandria, an otherwise unknown place in Egypt, and was educated in Alexandria . He is said to have lived there until around 135 AD. He spread his teaching in Egypt ( Aegyptus ) before going to Rome . In research, this information is considered plausible, although not confirmed. After Irenaeus of Lyon he came to Rome under Bishop Hyginus († 142) and worked there unchallenged as a free theological teacher until the time of Bishop Anicetus (around 154-166). After Epiphanius he went to Cyprus, apparently after his stay in Rome. Presumably he moved from Rome to Cyprus before 161 .

Teaching

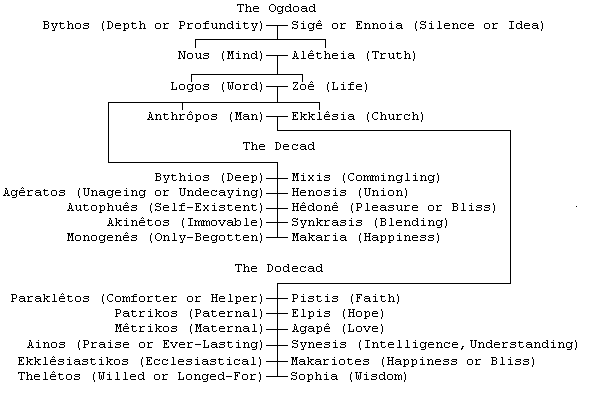

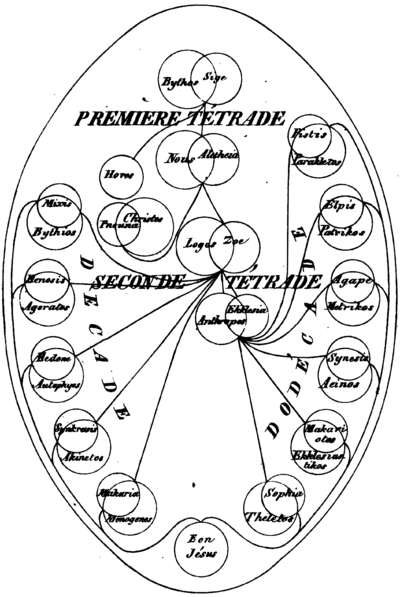

His teachings are seen as being influenced by Zoroastrianism , Middle Platonism and the Ophites . Little can be said with certainty about the teachings of Valentinus. Since most sources do not differentiate between his teaching and the views of later Valentinians, it is difficult to determine and in research controversial how much of the later Valentinian system goes back to the founder himself. At least some doctrinal statements can be inferred from the fragments. According to them, man was created imperfectly by angels, but perfected by the supreme God in the act of creation according to a heavenly model . The world is a well-ordered creation that is permeated by God's spirit. The Father is the (divine) source of things, he is the eternal and unconscious unity, the unnamable, the depth, the perfect aeon. Out of the need for love, after some with the 'stillness of thought' as his wife, he created the spirit ( ancient Greek νοῦς nous ) and the truth. Reason ( λόγος lógos ) and life sprouted from them , from these in turn the ideal man and the ideal church, and so other couples, including Christ and the Holy Spirit ( ancient Greek ἅγιον πνεῦμα hágion pneûma ). The totality of all 30 eons is called the pleroma ( πλήρωμα pléroma ) the fullness of the spirit world.

The revelation of the Most High God through his Son Jesus Christ cleanses the corrupted heart of man. The earthly Jesus of Nazareth is understood as a divine being: He eats and drinks, but has no digestion.

According to Martin R. von Ostheim (2013), the gnosis was a syncretistic religion , which had incorporated Christian, Stoic , Platonic and Pythagorean elements into the Valentian gnosis and transformed them into an interpretatio gnostica . The gods are called eons in the Valentian Gnosis (Greek ἀιών aiṓn "eternity"). They are spirit beings that mostly appear in pairs (syzygies). The Valentian school describes thirty eons. The totality of the highest eons is called Pléroma (Greek, πλήρωμα pléroma "fullness").

A central text is the hymn with the title harvest (théros) , which describes a vision of Valentinus: "I see everything suspended by Pneuma / I recognize everything as being carried by Pneuma: / flesh attached to soul, / soul bound to air, / Air hung on ether , / fruit brought forth from the deep, / a child brought forth from the womb. ”In the model of the cosmos presented here, at the top is the pleroma , the realm of pure spirit, below the pneuma, below this the ether below that the air and finally the matter or the flesh. The spirit of the visionary, which has penetrated to the pleroma, sees the lower areas from there and at the same time perceives the processes in the "depth" of the deity, where the Logos is conceived and born.

Even ancient opponents of Valentinianism brought the ideas of the current they opposed to Platonism and Pythagoreanism in order to discredit it. This was a standard anti-heretic argument. The church writer Tertullian repeatedly referred to Valentinus as a Platonist, and Filastrius of Brescia accused him of being more of a Pythagorean than a Christian. Hippolytus of Rome claimed that Valentinus' heresy contained the Pythagorean and Platonic teachings. Pythagoras and Plato once drew their teaching from Egyptian tradition and tailored it for the Greeks, and Valentinus tacitly adopted it from them and tried to create something of his own from it. In fact, Valentinus had a good philosophical education, he knew about Platonic cosmology and made use of it. However, he also came to non-Platonic results and can therefore only be regarded as a Platonist to a limited extent.

Clement of Alexandria reported that Valentinus is said to have been a follower of the Gnostic Theudas around the year 110 AD , and Theudas in turn is said to have been a follower of Paul . Valentinus said that Theudas imparted to him the 'secret wisdom' that Paul had privately taught his inner circle. Above all, the Pauline connection with his visionary encounter with the risen Christ (see Rom 16.25 EU , 1 Cor 2.7 EU , 2 Cor 12 EU ), which was an essential aspect of the 'secret teaching'.

According to Valentius, Jesus also shared certain secrets with his close followers ( disciples ) during his lifetime, but kept the enigmata hidden from outsiders, Mk 4.11 EU . And in the gospel according to Matthew he said that she would understand the secrets of the kingdom of heaven, but that this was not given to the others in Mt 13.11 EU .

In the text fund of the Nag Hammadi writings it was shown that Valentian Gnosticism is completely different from the dualism of other disciplines. The theme of the ' oneness of God' dominates the beginning of the Tractatus Tripartitus , a work assigned to the Valentian school or to Valentinus himself.

reception

The later so-called Valentinians at the time of Valentinus' activity in Rome were not a religiously organized cult community or sect, but a group within the urban Roman Christian large church whose members did not define themselves as "Valentinians", but simply themselves Called "Christians". It was only later that, as a result of the exclusion from the main church, a cult community was formed, at least in part.

The Valentinianism was one of the most widespread Gnostic-Christian movements. It developed in an Italian and an Eastern ("Anatolian") form. The Western school traditionally includes the Valentine teachers Alexander, Florinus, Herakleon , Ptolemy , Secundus and Theotimus, the Eastern Axionicus (Axionikos), Markos the magician and Theodotus of Byzantium . It is possible that Bardesanes also belonged to the eastern currents of Valentinianism.

In modern times, church historians classified Valentinus as an arch heretic until the 19th century, uncritically adopting information from large church sources. The more recent research paints a complex, differentiated picture, whereby many questions remain unanswered because of the unfavorable source situation.

For Daniel Dawson, Valentinus is very free and creative with biblical texts and sees the real origin of truth in visionary experiences that interpret the scriptures. Accordingly, Valentinus transforms the drama of writing into a "psychodrama". John Behr sees Valentinus as the leader of a group of Christians who are prone to speculation. For him, in Valentinus the difference between writing and commentary, writing and interpretation becomes blurred. Christoph Markschies , who limited himself to the direct fragments of Valentinus in his assessment of the teaching, describes him as "a thinker who at best prepares the way to the great systems of 'Gnosis', but does not yet go it himself".

Works

Valentinus wrote lesson letters , sermons, and hymns that were collected by his students. Eight fragments that are believed to be genuine have been preserved .

Six of them are passages from letters and sermons quoted by Clemens of Alexandria , the seventh is a quotation from Hippolytus of Rome , the eighth a hymn passed down by Hippolytus. Clemens mentions a dogmatic text on the three natures ( περὶ τῶν τριῶν φύσεων ), which is lost.

According to Philip Schaff , a fragment of it may have been preserved at Photios .

Various other writings such as the Gospel of Truth , the Letter to Diognet , the Letter to Rheginus, and the Letter to Pistis Sophia were ascribed to Valentinus by individual authors, but these assumptions are speculative. In the discoveries of Nag Hammadi important documents and texts for the study of Gnosis included. The writings come from different directions of the Gnosis, so there are writings of the Valentinians and the Setian Gnosis .

From Valentinus or his environment (selection, allocation disputed):

- Tractatus tripartitus

- About the three natures ( περὶ τῶν τριῶν φύσεων )

- Gospel of truth

literature

- Alexander Böhlig , Christoph Markschies : Gnosis and Manichaeism: Research and studies on texts by Valentin and Mani as well as on the libraries of Nag Hammadi and Medinet Madi. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1994, ISBN 3-11-014294-5 .

- Alexander Böhling: Gnosis and Syncretism. Collected essays on the history of religion in late antiquity. 1st part, Mohr, Tübingen 1989, ISBN 3-16-145299-2 ( online as PDF, 18.6 MB )

- Hans Leisegang : The Gnosis. 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-520-03205-8 , pp. 281-297

- Christoph Markschies: Valentinus Gnosticus? Investigations on Valentine Gnosis with a Commentary on the Fragments of Valentine. Mohr, Tübingen 1992, ISBN 3-16-145993-8 .

- Christoph Markschies: Valentin / Valentinianer. In: Theological Real Encyclopedia . Volume 34, Berlin / New York 2002, pp. 495-500 Google Booksearch

- Einar Thomassen: Valentinus and Valentinianism. In: Christoph Riedweg et al. (Hrsg.): Philosophy of the imperial era and late antiquity (= outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 5/1). Schwabe, Basel 2018, ISBN 978-3-7965-3698-4 , pp. 867–873, 1083 f.

- Klaus-Gunther Wesseling : Valentinos. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 12, Bautz, Herzberg 1997, ISBN 3-88309-068-9 , Sp. 1067-1084.

Web links

- Literature by and about Valentinus in the catalog of the German National Library

References and comments

- ↑ Markus Vinzent : The resurrection of Christ in early Christianity. Herder Verlag, Freiburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-451-31212-0 , pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion 31,2,2 f .; 31.7.1.

- ↑ Christoph Markschies: Valentinus Gnosticus? Tübingen 1992, pp. 314-331.

- ^ Irenaeus of Lyons: Adversus haereses 3, 4, 3.

- ↑ Epiphanius of Salamis: Panarion 31,7,2.

- ↑ Christoph Markschies: Valentinus Gnosticus? Tübingen 1992, pp. 331-334.

- ↑ George Robert Stow Mead , Helena Petrovna Blavatsky : Pistis Sophia. Lucifer 6 (1890) (33), pp. 230-239. London: The Theosophical Publishing Society; Compare also Epiphanios of Salamis , Adversus haereses. I 31.5-6

- ^ Christoph Markschies: Valentin / Valentinianer. In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Volume 34, Berlin / New York 2002, pp. 495–500, here: 496 f .; Einar Thomassen: Valentinus and Valentinianism. In: Christoph Riedweg u. a. (Ed.): Philosophy of the Imperial Era and Late Antiquity (= Outline of the History of Philosophy. The Philosophy of Antiquity. Volume 5/1), Basel 2018, pp. 867–873.

- ↑ Martin R. von Ostheim : Self-redemption through knowledge. The Gnosis in the 2nd Century AD Schwabe, Basel 2013, ISBN 978-3-7965-2894-1 , pp. 7–8; 11

- ↑ Martin R. von Ostheim : Self-redemption through knowledge. The Gnosis in the 2nd Century AD Schwabe, Basel 2013, ISBN 978-3-7965-2894-1 , pp. 15-16; 71

- ↑ See on the text and translation by Christoph Markschies: Valentinus Gnosticus? Tübingen 1992, pp. 218-230.

- ↑ Hans Leisegang : The Gnosis. A. Kröner, Leipzig 1924. 5th edition, Kröner, Stuttgart 1985. ISBN 3-520-03205-8 , p. 283.

- ^ Documents from Christoph Markschies: Valentinus Gnosticus? Tübingen 1992, p. 323 f.

- ↑ Hippolyt: Refutatio omnium haeresium 6.21.

- ↑ Christoph Markschies : Valentinus Gnosticus? Tübingen 1992, pp. 324-330.

- ↑ Clemens , Stromateis 7.17.106.4.

- ↑ Tobias Nicklas , Andreas Merkt , Joseph Verheyden: Ancient Perspectives on Paul. Vol. 102 Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus / Studies on the Environment of the New Testament. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-647-59359-3 , p. 193 ( [1] on books.google.de)

- ↑ Plérome de Valentin from Jacques Matter : Histoire critique du Gnosticisme. 1826, Vol. II, Plate II.

- ↑ Elaine Pagels : Temptation through Knowledge. The Gnostic Gospels. Suhrkamp Taschenbuch 1456, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-518-37956-9 , p. 52

- ↑ Elaine Pagels : Temptation through Knowledge. The Gnostic Gospels. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-518-37956-9 (Suhrkamp Taschenbuch 1456), pp. 73-74 (Original: The Gnostic Gospels. New York 1979; German by Angelika Schweikhart: Insel, Frankfurt / M. 1981) .

- ^ Christoph Markschies: Valentin / Valentinianer. In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Volume 34, Berlin / New York 2002, pp. 495–500, here: pp. 498 f.

- ^ Christoph Markschies: Valentin / Valentinianer. In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Volume 34, Berlin / New York 2002, pp. 495–500, here: 498.

- ↑ See the balance sheet with Christoph Markschies: Valentinus Gnosticus? Tübingen 1992, pp. 388-407.

- ^ Daniel Dawson : Allegorical Readers and Cultural Revision in Ancient Alexandria. Berkeley 1992, pp. 165, 168.

- ^ John Behr : The Way to Nicea , Crestwood 2001, pp. 20-22.

- ↑ Christoph Markschies: The Gnosis. 3rd edition, CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-44773-0 , p. 90.

- ↑ Hippolyt, Refutatio omnium haeresium 6,42,2.

- ↑ Hippolyt, Refutatio omnium haeresium 6,37,7.

- ^ Photios , Library 230.

- ^ Philip Schaff : Valentinus and his School. In: New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge.

- ↑ See also Einar Thomassen: Valentinus und der Valentinianismus. In: Christoph Riedweg u. a. (Ed.): Philosophy of the Imperial Era and Late Antiquity (= Outline of the History of Philosophy. The Philosophy of Antiquity. Volume 5/1), Basel 2018, pp. 867–873, here: 867 f .; Christoph Markschies : Valentin / Valentinianer. In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Volume 34, Berlin / New York 2002, pp. 495–500, here: 496; Christoph Markschies: Valentinus Gnosticus? Tübingen 1992, pp. 337-363.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Valentinus |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Valentinos; Valentine; Valentinian; Valentius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Gnostic |

| DATE OF BIRTH | at 100 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | uncertain: Phrenobis , Egypt |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 160 |