Liturgical reform

The liturgical reform is usually the comprehensive one already under Pope Pius XII. started and then decided by the Second Vatican Council ( 2. Vaticanum ) and the Popes Paul VI. and John Paul II carried out a general renewal ( Latin instauratio ) of the Roman Catholic liturgy , especially the Holy Mass , the Liturgy of the Hours and the rites of the dispensing of the sacraments , in the 20th century.

The liturgical reform (s) of the 20th century find their roots in the liturgical movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Germany, Belgium and France. Pope Pius XII channeled their endeavors in the encyclical Mediator Dei . Under the decisive influence of German and French scholarship, their concern changed from a merely better penetration of the liturgy to genuine reform efforts. Groundbreaking preparatory work was primarily done by Romano Guardini , Pius Parsch , Odo Casel and, in an outstanding way, Josef Andreas Jungmann . According to the Council Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium, which was promulgated on December 4, 1963, the Consilium was responsible for the implementation of the liturgy constitution . This happened in a first stage until 1965 and ended in 1969 with the publication of the new Missale Romanum , largely by the secretary of the Consilium Annibale Bugnini and within the Consilium by Johannes Wagner . This was followed in a further stage by the translation into the vernacular.

Earlier liturgical reforms

Beginnings: liturgical movement, mediator Dei and scientific processing in Germany and France

Motu proprio Tra le sollecitudini Pius X. (1903)

A central term for the liturgical reform after the Second Vatican Council was the Participatio actuosa of the church people. The term is first found in the Motu proprio Tra le sollecitudini Pope Pius X. from 1903. The writing actually mainly referred to church music; it particularly wanted the more frequent use of Gregorian chant and forbade the use of castrati in church music. However, paragraph 3 also stated:

"Essendo, infatti, Nostro vivissimo desiderio che il vero spirito cristiano rifiorisca per ogni modo e si mantenga nei fedeli tutti, è necessario provvedere prima di ogni altra cosa alla santità e dignità del tempio, dove appunto i fedeli si si si radun sua prima ed indispensabile fonte, che è la partecipazione attiva [emphasis not in the original] ai sacrosanti misteri e alla preghiera pubblica e solenne della Chiesa. "

“Because it is a matter of the heart to us that the truly Christian spirit blossoms again everywhere in all believers and remains undiminished. Therefore, we must above all care for the holiness and dignity of the house of God. Because there the believers gather to draw this spirit from the first and indispensable source, namely from active participation [emphasis not in the original] in the most holy mysteries and the public, solemn prayer of the Church. "

In the context of this letter, the participazione attiva did not yet have the fundamental and far-reaching significance of the post-conciliar texts, but initially referred to participation in church chant.

In addition to reforming church music, Pius X also carried out the following liturgical and disciplinary reforms, for which he issued the following letters:

- Motu proprio Sacra Tridentina Synodus (1905): on the regular communion of the faithful,

- Decree Quam singulari (1910): to reduce the age from which children can receive communion,

- Apostolic Constitution Divino afflatu (1911): on the reform of the breviary ,

- Motu proprio Abhinc duos annos (1913): for the reform of the liturgical year.

Liturgical movement

The liturgical reform of Pius V following the Council of Trent had reformed and unified the liturgical books in order to stimulate the liturgical life of the clergy and the faithful. The renewal movement in the 20th century went in the opposite direction: it arose out of a pastoral concern, which resulted in the revision of the rubrics and regulations.

Solesmes in the 19th Century: Liturgical Education

The efforts to reform the liturgy begun by Pope Pius X were strengthened by the liturgical movement that arose in the second half of the 19th century . It goes back to the first abbot of the Benedictine monastery of Solesmes , Dom Guéranger ; from him comes the name of the movement as "liturgical movement" (French: 'mouvement liturgique'). His Institutions liturgiques (1840) and his 24-volume L'Année liturgique aimed to promote a greater understanding of the liturgy and to revive the singing of Gregorian chant . This first phase of the liturgical movement was not aimed at changing the liturgy, but at a deeper understanding of the existing liturgy through increased liturgical education.

Beuron and Maria Laach: The Liturgy of the Early Church and the Paschal Mystery

In Germany, interest in the liturgy increased as early as the 19th century, as shown by the work of the Catholic School in Tübingen ( Johann Adam Möhler , Franz Anton Staudenmaier and Valentin Thalhofer ). The decisive impetus nonetheless came from Solesmes: the efforts there were primarily taken up by the Benedictine monastery of Beuron . The most important instrument to bring the liturgy closer to laypeople was the publication of a lay missal (the so-called Schott ) by Anselm Schott . Schott understood his Volksmessbuch as a compendium of L'Année liturgique ; the explanations of the bulkhead are clearly inspired by him. Nine years later he also published a Latin-German Vesper book ( Vesperale Romanum) , which for the first time introduced the term “liturgical movement” in the German-speaking world.

Another center of the liturgical movement in Germany was the Maria Laach Abbey under its abbot Ildefons Herwegen and his pupil Odo Casel (Ecclesia Orans, 1923, Das christliche Kultmysterium, 1932). Theologically extremely innovative, the mystery as the Paschal mystery is the focus of Casel's liturgical understanding. In celebrating this mystery, Christ himself remains sanctifyingly present through signs and rites. The liturgy is therefore not primarily a latreus act of people (in the sense of the offering of a cult owed to God), but a saving act of God himself for people through whom they gain a share in the mystery of salvation.

In the Maria Laach crypt masses there were liturgical experiments early on, such as mass versus populum . Above all, Romano Guardini had prepared theological standards for a liturgical reform within this movement with his work Vom Geist der Liturgie (1918). The liturgical magazines published by Johannes Pinsk also received a great deal of attention in the 1930s . Herwegen especially tried to embed the intended character of the liturgy ideologically.

“The individual, raised by the Renaissance and liberalism, has really lived out. It realizes that it can only mature into personality in connection with a completely objective institution. It calls for the community [...]

The age of socialism knows communities, but only those that form an accumulation of atoms of individuals. But our longing is for the organic, for a lively community. "

Contrary to Guardini's actual intentions, he did not shy away from political equations:

"What the liturgical movement is in the religious field is fascism in the political field."

At the same time, the concentration on the liturgy in Germany in the 1930s can be explained by the restrictions on youth work under National Socialism . While the extra-liturgical youth work was increasingly restricted, the liturgy remained as a place of refuge. In addition to the communal mass, the Compline in the form of the “German Compline” was a particularly popular pre-war liturgical form. Ludwig Wolker's church prayer for the community service of Catholic youth (1930) achieved a circulation of over nine million. This publication gave the German standard text of the liturgy, which had been developed on a private initiative in Cologne since 1928, a wide distribution. It was received everywhere and taken over in folk mess books and diocesan hymns and remained the valid German standard text for the Ordo Missae and the canon of the German mass until May 1971.

In Austria, the Augustinian canon Pius Parsch was one of the most important faces of the movement. In the meantime she had shifted her attention from a better understanding of the liturgy to real change . From 1922 on, the betsing mass was introduced in Parsch in the form of the community mass in St. Gertrud (Klosterneuburg) ; he also introduced the greeting of peace and the procession to the offertory in the liturgy. Outside the German-speaking area, the so-called missa dialogata developed , which received the approval of the Congregation for Rites in 1922 for the Eucharistic Congress in Rome in 1922 .

Lambert Beauduin, the Mechelen event and the pastoral liturgy

While the liturgy of the old church was the main focus in the German-speaking countries, in another important center at the beginning of the 20th century - Belgium - the focus of the initiator there, Lambert Beauduin , was primarily on the pastoral aspect of the liturgy (La Piété de l 'église, 1914) . He was also a Benedictine ( Abbey of Mont César ) and is considered a “champion for a 'democratization of the liturgy'”. In 1924 he met Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli , who later became Pope John XXIII. , know; he was deeply impressed by Beauduin's ecumenical theology . For him, the liturgy was the means par excellence to remain in unity with the Church or to find one's way back into it, as he explained at the Mechelen Congress in 1909. Theologically, he viewed the liturgy as a cultic act of the church, which applies to the risen Christ; at the same time this cult is part of the history of salvation through the priesthood of Christ .

Italy and Spain: Little influence of the liturgical movement

In the other Romansh-speaking countries, the liturgical movement never turned into a liturgical reform movement. In Spain it remained essentially a movement for the cultivation of Gregorian chant until the 1960s. It received its first impulses in the 19th century from Solesmes. The centers of the movement were also here the abbeys, namely Santo Domingo de Silos , Santa Cecilia de Montserrat (under Gregori Suñol ) and the Montserrat monastery . A key event of the movement in Spain was the Montserrat liturgical congress in 1915.

Developments in Italy also remained much more timid than in Germany, France and Belgium. Like all theological research, liturgical research in Italy was not very innovative. The reasons for this are the deeply rooted traditional popular piety in Italy and the lack of engagement of the episcopate in the movement.

Certain Italian forerunners can be found as early as the 18th century: These include the controversia di Crema on the distribution of communion during Holy Mass (1737–1742), the Synod of Pistoia (1786), the studies of Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusas (1649 –1713) and Ludovico Antonio Muratoris and, in the 19th century, those Antonio Rosminis (Delle cinque piaghe della santa Chiesa, 1848), who particularly criticized the sharp separation between people and clergy . In the early 20th century, the bishop of Ivrea , Matteo Angelo Filipello , stood out with a pastoral letter (La liturgia parrocchiale, 1914) . In the Diocese of Cremona , Bishop Geremia Bonomelli campaigned in 1913 (pastoral letter La Chiesa ) to ensure that the faithful could sing and understand the ordinance of the Mass . The effort is not aimed at reform, but at education for a better understanding of the fair. The efforts of the Archbishop of Milan , Ildefonso Schusters , were inspired by Benedictines .

The actual starting point of the liturgical movement in Italy can only be regarded as the year 1914; This year the monks of the Benedictine Abbey of Santa Maria di Finalpia published the Rivista liturgica for the first time under the direction of Emanuele Caronti . She paid particular attention to revealing the theological foundation of the liturgy for the first time in Italy. This led to the following concrete measures: The Sacred Heart Missionaries in Rome published the foglietto della domenica, which was supposed to better explain to the faithful that they should take part in the mass. In Genoa , the Commenda di San Giovanni di Pré , based on Giacomo Moglia's first attempts in 1912, has been publishing paraphrases of the prayer texts of the Mass since 1915, which are aimed particularly at the youth. Finally, in 1934, the first Italian liturgical congress took place in Genoa. During this time, Francesco Tonolo (through popular missals) and the Gioventù Femminile di Azione Cattolica also made a particular contribution to liturgical education . Lastly, there is the influence of the Opera della regalità di NSGC , founded in 1928 by Agostino Gemelli , which between 1931 and 1945 tried to increase liturgical understanding with the weekly brochures La Santa Messa per il popolo italiano . Organizationally, fixed structures crystallized only after the Second World War with the establishment of the Centro di Azione Liturgica in Parma , just a month after the publication of the encyclical Mediator Dei , out.

United States: St. John's Abbey in Collegeville

In the United States, the liturgical movement was also limited in its effectiveness from the start. The average Catholic there knew nothing more about the liturgical movement than that it was a “splinter group” of priests and some committed lay people who were particularly active in monastic environments; the main center of the movement was St. John's Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota under Dom Virgil Michel and Godfrey Diekman . Its two main goals were a wider use of the vernacular, the dialogue mass and a great interest in Gregorian chant and some archaic liturgical practices. The liturgical reform in the United States can therefore neither be viewed as a movement of the ecclesiastical base, nor has the liturgical reform been an overriding goal of the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

Germany after World War II: Concrete Steps towards Reforms

The liturgical movement was also exposed to criticism, especially in Germany. The German bishops therefore founded a commission to investigate the liturgical movement under the leadership of Bishops Albert Stohr and Simon Konrad Landersdorfer .

The demands of the liturgical movement finally grew into concrete reform steps through the academic work-up in Germany. The Relator of Coetus X for the reform of the Ordo Missae within the Consilium for the implementation of the Council resolutions from 1964, Johannes Wagner noted in 1982,

"That [...] the name must always stand above the reform of the Mass of the Second Vatican Council: Josef Andreas Jungmann ."

The first meetings always had to take place with great precaution. The starting point is a meeting from January 1st to 3rd, 1948 in Banz Monastery . The editor of the Roman magazine Ephemerides liturgicae , Annibale Bugnini, had invited to this. On January 28, 1948, Bugnini sent four questions in a confidential letter to several employees of the magazine, including Theodor Klauser , and requested statements on the reform of the breviary , the calendar, the martyrology and the reform of all liturgical books. This first meeting in Kloster Banz focused on reforming the breviary. On this occasion, Jungmann was also asked "in silence" to distill the knowledge gathered during the creation of his monumental opus magnum , Missarum sollemnia (1948), into a basis for discussion on a concrete measurement reform.

In Bad Homburg's Dreikaiserhof , Jungmann was finally able to submit his suggestions from November 29 to December 2, 1949:

“Perhaps the pre-fair could take place at the Sedilien . The act of sacrifice should stand out from the reading part, the incision of the canon and paternoster should be recognizable. All the individual parts should fulfill their function more strongly. For example, the readings [...] should be enriched. [...] After the readings, the general prayer should be reinstated [...] The meaning of the offertory could easily be made clearer. Only now should the chalice be brought to the altar , and the idea of gratias agere should come into its own. [...] Several prefession forms should be available for Sunday . . The canon, on the other hand, could be shortened [...] The names of saints in the canon would have to be revised, the final doxology at the end of the canon emphasized. The Kommunionausspendung could not Confiteor , Misereatur and indulgentiam done, but that should Ecce Agnus [...] be preserved. […] Furthermore, at the beginning of the Mass, the Psalm Judica could be restricted to the real acess . The mass itself begins at the altar with a deep bow to God. The offertorial prayers could be shortened. [...] "

A second session followed “with the windows and doors closed” in the retreat house Himmelspforten near Würzburg from December 12th to 14th, 1950. After a meeting of the Liturgical Institute in Trier with the Paris Center de Pastorale Liturgique in Luxembourg , some key points emerged, Jungmanns “Dream in the Heart”, which was presented at the international liturgical study meeting in Maria Laach from July 12th to 15th, 1951 and published in the Herder correspondence . The Congregation for Rites , especially Joseph Löw , accepted these suggestions with goodwill.

International Liturgical Study Meetings (1950–1960)

The first informal meetings soon took on the more solid organizational structure of the International Liturgical Study Meetings ; True to the principle that “in German votes in the field of liturgy […] will only be successful if it is shared by France”, German and French liturgical studies formed the backbone of the scientific preparation of the later Council text. This cooperation resulted in seven international liturgical study meetings , along with some others :

- a friendship meeting in Luxembourg from July 23 to 24, 1950,

- the first international liturgical study meeting in Maria Laach from July 12th to 15th, 1951,

- the Second International Liturgical Study Meeting on Mount Odile from October 20 to 24, 1952,

- the Third International Liturgical Study Meeting in Lugano from September 14th to 18th, 1953,

- the Fourth International Liturgical Study Meeting in Leuven from September 12th to 15th, 1954,

- the Fifth International Liturgical Study Meeting at the Pastoral Liturgical Congress of Assisi from September 14th to 17th, 1956,

- the Sixth International Liturgical Study Meeting in Montserrat from September 8th to 12th, 1958,

- the Trier exhibition of the Holy Rock 1959,

- Meeting in Nijmegen and Eichstätt 1960,

- the Seventh International Liturgical Study Meeting in Munich from July 20 to August 3, 1960.

Mediator Dei (1947)

Because of its practical experience in the Catholic youth movement , the Liturgical Movement played a major role in the creation of the (first) encyclical Mediator Dei by Pope Pius XII, which was dedicated to the liturgy after the Second World War .

She developed the principles on which the entire Catholic liturgical reform of the 20th century is based:

- The truthfulness of the holy signs, especially when the celebrations are timed (e.g. Easter vigil is no longer on Holy Saturday morning);

- liturgical consideration of the active participation of the whole people of God;

- The renewal does not consist in the restoration of a certain phase of the development of the liturgy (for example the time of Pope Gregory the Great), but draws on the whole treasure of the church's worship life by eliminating less successful inventions and repeating important symbolic acts that were wrongly forgotten introduces.

The encyclical was both pastoral and theological in nature. From a pastoral point of view, the main aim was to capture and channel the fermentation of the liturgical movement. From a theological point of view, the Pope insisted above all that the liturgy should not be viewed as just an external, formal act that had to be carried out in rubricistically correct rite et recte . Rather, these rites are deeply penetrated theologically:

“Sacra igitur Liturgia cultum publicum constituit, quem Redemptor noster, Ecclesiae Caput, caelesti Patri habet; quemque christifidelium societas Conditori suo et per ipsum aeterno Patri tribuit; utique omnia breviter perstringamus, integrum constituit publicum cultum mystici Iesu Christi Corporis , Capitis nempe membrorumque eius. "

“The holy liturgy therefore constitutes the public cult which our Redeemer, Head of the Church, pays to the Heavenly Father and which the community of believers in Christ offers to its Founder and through him to the Eternal Father; to summarize it briefly: it represents the entire public worship of the mystical body of Jesus Christ, namely his head and his members. "

The theological starting point of the Mass is therefore the priesthood of Jesus Christ. His own priestly mediation in God the Father during the fullness of time thus continues in the founded by Christ Church and its liturgy continues in two aspect: First, in the worship and glorification of God and the proclamation of his greatness and glory, and then - sacramentally - in the Sanctification of the people.

"Quapropter in omni actione liturgica una cum Ecclesia praesens adest divinus eius Conditor."

"Therefore, in every liturgical act, her divine founder is present at the same time as the Church."

The encyclical also takes up the participatio actuosa from Tra le sollecitudini . It differentiates this participation from three aspects:

- external: this means external participation, i.e. presence,

- inwardly: this means the inner disposition through the pious devotion of heart and soul, and

- sacramental.

Pius XII. With the Motu Proprio In Cotidianis Precibus on March 24, 1945, allowed a new translation of the Psalter for the Breviary from Hebrew into Latin, which was only used briefly and generally less successful , and which should be closer to Classical Latin than the late Latin of the previously used Translation in the Vulgate .

As early as 1946, he set up a commission with eight members , the so-called Commissio Piana, for the renewal of the Catholic liturgy. She began her work in 1948 under the secretary Annibale Bugnini and in the same year published the policy paper Memoria sulla Riforma liturgica .

Reform of the Holy Week by Pius XII. (1951-1956)

As early as 1951, the Easter vigil was reformed by the decree De solemni vigilia paschali instauranda on November 16, 1955, the entire Holy Week through Maxima redemptionis . Another small change resulted from the admission of evening masses and the associated lowering of the requirements for eucharistic sobriety by Christ Dominus from 1953. With Cum hac nostra aetate and De musica sacra et sacra liturgia , Pius XII. Furthermore, minor reforms of the breviary and the rubrics of the missal as well as church music (approval of songs in the vernacular in exceptional cases).

Codex rubricarum (1960) and editio typica des Breviers and Missales (1961/62) by John XXIII.

Another significant change was made by Pope John XXIII. made publication of under Pius XII. prepared Codex Rubricarum on July 27, 1960. The reorganization was generally prescribed without granting special rights or exceptions. Rather, all the exceptions and special regulations that still existed in the Roman rite were revoked at the same time. Hermann Schmidt interpreted their hasty pre-conciliar promulgation as follows:

"For better or worse, one had to see a work in this edition that was supposed to anticipate the later decisions of the Council, and it was later to show how little this assumption was made out of thin air."

Only one year later, on April 5, 1961, a new editio typica des Breviary appeared, and again a year later, on June 23, 1962, an editio typica des Missale Romanum ; these so-called. Liturgy of 1962 was the last pre-conciliar Missal still with the Bull Quo primum Pius V issued.

Second Vatican Council: Sacrosanctum Concilium (1963)

History of origin

From the Pope Pius XII. In 1959, the Commission established the Preparatory Commission for the Liturgy Constitution of the Second Vatican Council . Because of the thorough preparatory work, their draft, which was signed by the responsible Cardinal Gaetano Cicognani in 1962 just a few days before his death, escaped the fate of other more than 70 curial drafts, which were rejected as unusable by the assembled Council Fathers. The liturgy draft, however, met with general approval.

On December 4, 1963, the liturgy constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium (common abbreviation: SC) was published as the first document of the 2nd Vatican Council. The subject of the "general renewal of the liturgy" (SC 21) thus resolved is the entire church service:

- the Eucharistic celebration ,

- the other sacraments and the sacramentals ,

- the daily prayer ,

- the calendar , the feasts and times ,

- the sacred music and sacred art.

In the age of a Catholic Church represented on all continents, the Council was firmly convinced of the need for the liturgical reform that it was continuing to pursue: the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium was approved in public on December 4, 1963 by the Council Fathers in 2147 ("placet") against only 4 (" non placet “) votes accepted and by Pope Paul VI. promulgates . In the spirit and in accordance with the principles of this liturgy constitution, the liturgical orders and books of the Roman rite, including the Roman Missal , were renewed in the following years - as required quickly ( quam primum : SC 25) - and by the Popes, Paul VI. to John Paul II, officially published.

Sacrosanctum Concilium tried to balance the views of different "camps" within the council. His objective was therefore twofold, on the one hand the preservation of all valid rites, on the other hand their careful examination of the need for reform for the people of today:

“Traditioni denique fideliter obsequens, Sacrosanctum Concilium declarat Sanctam Matrem Ecclesiam omnes rite legitime agnitos aequo iure atque honore habere, eosque in posterum servari et omnimode foveri velle, atque optat ut, ubi opus sit, caute ex integrouris novo voscantore tradition recognis et mentem sanaigore , pro hodiernis adiunctis et necessitatibus, donentur. "

“Faithfully obedient to tradition, the Holy Council finally declares that the Holy Mother Church grants equal rights and equal honor to all legally recognized rites, that she will preserve these rites in the future and promote them in every way, and it is her wish that they as far as necessary, carefully tested anew, according to the spirit of healthy tradition, endowed with new strength for today's conditions and needs. "

Understanding of liturgy and the Church

The way in which the Council approached the liturgy, however, was very different from the previous approaches, in that it started from the various forms of participation in it - external / internal and public / private. The conciliar definition of the liturgy is strongly reminiscent of the two-dimensional, Latreutisch-sacramental understanding of liturgy from Mediator Dei and defines it as the public cult of the universal Church:

“The liturgy is rightly regarded as the exercise of the priesthood of Jesus Christ; by sensible signs the sanctification of the human being is signified in it and effected in each individual way and by the mystical body of Jesus Christ, d. H. the head and the members, the entire public cult [emphasis not given in the original]. As a result, every liturgical celebration, as the work of Christ the priest and his body, who is the Church, is primarily a sacred act, the effectiveness of which no other activity of the Church attains in rank or measure.

In the earthly liturgy we partake in anticipation of that heavenly liturgy which is celebrated in the holy city of Jerusalem , to which we are on pilgrimage, where Christ sits at the right hand of God, the servant of the sanctuary and the true tent. In the earthly liturgy we sing the praises of glory to the Lord with the whole host of the heavenly host . In it we venerate the memory of the saints and hope to share and fellowship with them. In it we await the Savior, our Lord Jesus Christ, until he appears as our life and we appear with him in glory. "

In addition to this influence, the influence of Odo Casel's mystery theology is also clearly recognizable through the frequent mention of the Paschal mystery . The liturgy is therefore always a celebration of redemption and part of the divine plan of salvation with an eschatological dimension:

“As, therefore, Christ was sent by the Father, so he himself sent the Apostles filled with the Holy Spirit not only to preach the gospel of all creatures, the message that the Son of God tore us from the power of Satan by his death and resurrection and into the kingdom of the Father, but also to carry out the work of salvation they proclaimed through sacrifice and sacrament , around which the whole liturgical life revolves. [...] Since then, the Church has never stopped gathering to celebrate the Passover mystery [...] ”

Therefore the liturgical constitution is also considered groundbreaking for the later in Lumen Gentium unfolded ecclesiology of the Council. In addition to this mystical and eschatological dimension of the Church as a whole of the angels, saints and the whole earthly Church, so the whole people of God , however, a special attention is paid to concrete in a certain place and a certain time for the celebration of the liturgy gathered community . In the assembled local church , the universal church crystallizes .

The liturgy therefore understands Sacrosanctum Concilium as a "hierarchical and communal act" (SC 26–32). The various participants are assigned clearly defined tasks in the divine service in order to present the church in its organically structured unity (the “people of God, united and ordered among the bishops”); everyone should “in the exercise of his task only do that and all that is due to him from the nature of the matter and according to the liturgical rules” (SC 28). The liturgical tasks of lay people, i.e. acolytes, lecturers, commentators and members of the church choirs, are therefore a full liturgical service (SC 29).

Renewed liturgical books (SC 25) and reading regulations (SC 35 and 51)

The council commissioned a speedy ( quam primum ; SC 25) publication of the renewed liturgical books. It recognized that the aspect of worship and glorification is complemented by didactic and catechetical :

"Etsi sacra Liturgia est praecipue cultus divinae maiestatis, magnam etiam continet populi fidelis eruditionem."

"Although the sacred liturgy is above all a cult of divine majesty, it also contains a lot of instruction for the believing people."

Another main concern of the renewal was therefore that "the faithful [...] the treasury of the Bible should continue to be opened up" (SC 51). Therefore, a new, three-year reading order for the liturgy of the Mass was drawn up; until then a one-year cycle applied. On Sundays today there are two readings in addition to the Gospel opposite one in the so-called Tridentine Mass . Many days of the week today have their own reading order, while votive masses were read beforehand or the texts of the previous Sunday were repeated. A total of 12,000 of the 35,000 individual Bible verses are read within the three-year cycle , with the exception of the Book of Obadja all biblical books are taken into account. These values are many times higher than in the previous one-year reading order.

Previously, in the so-called Tridentine Mass , only one percent of the Old and 17 percent of the New Testament were read, but since the liturgical reform, 14 percent of the Old Testament and 71 percent of the New Testament texts have been read.

Worship languages (SC 36)

With regard to the languages in which Catholic worship is to be celebrated in the future, the Second Vatican Council expressly requested the continued use of the Latin language in the Latin rites, “unless there are special rights to the contrary”, and at the same time recognized that the people can be very useful ”(SC 36). Furthermore, it determined as a preceding general rule that the liturgical texts were to be designed in such a way that the Christian people could grasp and celebrate them “as easily as possible” (SC 21; active and conscious participation ). For the “masses celebrated with the people” the use of the mother tongue was allowed, “especially in the readings and in general prayer, as well as depending on the local conditions in the parts that belong to the people. However, provision should be made that the Christian believers can also speak or sing to one another in Latin the parts of the ordinance that are due to them. "(SC 54)

The formulation was generally perceived as a moderate compromise. Even in the preparatory commissions (Commissio Ante-Praeparatoria for the world episcopate) there had been far more extensive demands for the revival of the Latin language for lectures in seminars and theological faculties, but these were made obsolete at an early stage by the apostolic constitution Veterum sapientia . The constitution was viewed very critically, especially by moderate forces. The rather moderate Joseph Höffner therefore commented on the preparatory scheme of the liturgy constitution :

“The arguments which the Council Fathers have so far put forward on the question of the liturgical language are not drawn from Revelation, but from history, sociology or psychology. No theological or dogmatic quality can be attributed to these arguments […] Theologically and dogmatically there can be several liturgical languages in the Church of Christ […] What the scheme proposes regarding the vernacular languages is very moderate and does not intend to abolish the Latin language [… ] "

The traditional-conservative Alfons Maria Stickler also felt the formulation as an acceptable compromise between various extreme positions, which was therefore able to quickly reach an agreement at the beginning of the council:

“When the topic of the cult language was discussed in the council hall for a few days, I followed the whole progress with great attention, as well as the various formulations in the liturgy constitution afterwards until the final vote. I still remember very well how, after a few radical proposals, a Sicilian bishop stood up and implored the fathers to exercise caution and insight on this point, otherwise there would be the danger that the whole mass would be held in the vernacular, whereupon the whole Council auditorium burst into roaring laughter. "

Concelebration (SC 57-58)

The council wanted to allow the concelebration , that is, the common celebration of several priests at one altar, based on the Eastern Church model ; a separate concelebration rite should be created for this purpose (SC 58). This permission initially referred to (SC 57 § 1 No. 1):

- the mass of the consecration of chrism and the communion mass on Maundy Thursday .

- masses at councils , episcopal meetings and synods.

- the mass at the consecration of the abbot .

In addition, the decision on the concelebration is up to the local bishop in the following cases (SC 57 § 1 No. 2):

- the convent mass and the main mass in churches if the “spiritual well-being of the Christian believers” does not require individual celebrations;

- Mass at the various gatherings of world and religious priests.

The right to individual celebrations remained unaffected unless it was held simultaneously with a concelebration in the same church and on Maundy Thursday .

Justification of the new measurement regulations (SC 50)

The council wanted both the revaluation of older traditions and a pastoral, more communicative use of the Roman rite. The revision of the ordinance (Ordo missae) was therefore expressly commissioned by the Council Fathers (SC 50), who also specified the objectives:

- "That the real meaning of the individual parts and their mutual connection emerge more clearly" and

- “The pious and active participation of the faithful is facilitated” (ibid.).

This found its expression in the endeavor to create more clarity and simplicity in the liturgical sequence, to achieve a greater variety of liturgical texts (partly taken from older traditions) and to allow several Eucharistic Prayers (keeping the Canon Romanus as the first prayer).

Liturgy of the hour (SC 83-101)

According to SC 89, Lauds and Vespers as pivots of the Liturgy of the Hours should also emerge as such in a special way. The mother should only be kept in choir prayer as a night prayer, otherwise it should also be possible to pray at other times. their scope should be reduced. The Prim would eventually completely eliminated. For the choir prayer the third , sixth and non should be retained, but outside of which one of these so-called small hours can only be selected for the time of day.

Liturgical calendar (SC 102–111)

The council also ordered a reform of the liturgical calendar while respecting traditional customs and regulations. The main criteria of this reform should be the primacy of Sundays and the men's festivals. Two sections (SC 109 and 110) are devoted to Lent . The saints' festivals should take a back seat to the gentlemen's festivals and should be left to the respective local church (SC 111)

Implementation of the Council's resolutions: First reforms through the Consilium and the Altar Messbuch (1963–1965)

Overview of decrees and instructions

The Congregation for Holy Rites , the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Order of the Sacraments and the Consilium for the Execution of the Liturgy Constitution adopted the following measures as a result of the Sacrosanctum Concilium :

- Request from Pope Paul VI. to the Secretariat of the Council Commission for the Liturgy and to the Archbishop of Bologna , Giacomo Lercaro , for drawing up a plan for the establishment of a council for the implementation of the liturgy, the so-called Consilium ad exsequendam Constitutionem de Sacra Liturgie in December 1963

- Cardinal Lercaro then commissioned Annibale Bugnini , and on January 25, 1964 Paul VI set up the building. by the motu proprio Sacram Liturgiam also formally the Consilium , informally the Consilium had already met for the first time on January 15th of the same year. From April onwards, the so-called Coetus X was formed within the Consilium for the Ordo Missae .

- Decretum typicum Paul VI. on the use of the mother tongue in the liturgy

- Formula pro S. Communione of April 25, 1964: The previous formula is replaced by "Corpus Christ" - "Amen"

- Instruction Inter Oecumenici of September 26, 1964:

- Parts spoken or sung by the people or the Schola , as well as the readings, no longer have to be spoken privately by the celebrating priest, as was previously the case;

- Arranging translations into the vernacular and admitting the mother tongue to a certain extent;

- Abolition of Psalm 42 in step prayer , e.g. T. complete abolition of the step prayer;

- loud speaking of the Secreta and the final doxology ;

- common speaking of the Lord's Prayer ;

- Formula for giving communion "Corpus Christi", abolition of the sign of the cross when giving communion;

- Abolition of the final gospel and the Leonine prayers ;

- Reading, epistle and gospel are spoken to the people (at the ambo or altar), reading and epistle can be spoken by a lay person;

- Sermon as homily ;

- Introduction of the General Prayer

- De unica interpretatione textuum liturgicorum of October 16, 1964

- Kyriale simplex dated December 14, 1964

- Cantus in Missali Romano from December 14, 1964

- Variationes in Ordine Hebdomadae sanctae of March 7, 1965

- De praefatione in Missa of April 27, 1965: Indult for the use of the mother tongue in the prefaces .

The Council for the Execution of the Liturgy Constitution (so-called Consilium )

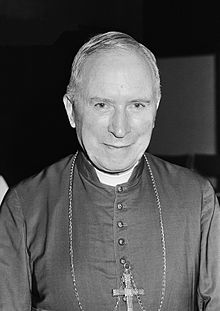

From 1964 the Consilium for the implementation of the liturgical constitution was active in order to renew the liturgical books according to the principles and guidelines of the Sacrosanctum Concilium . The chairmanship was initially held by the Archbishop of Bologna, Cardinal Giacomo Lercaro , and since 1968 Cardinal Benno Gut OSB. The Congregation for Divine Worship emerged in 1969 from the Consilium and the earlier Congregation for Rites. Secretary of the Consilium and then of the Congregation was Annibale Bugnini , who had been secretary of the Reform Commission of Pius XII since 1948 . and then the liturgical preparatory commission for the council. As part of the "general renewal of the liturgy" wanted by Vatican II, the order of the Mass , the Ordo missae , as ordered by the Council (SC 50), was thoroughly revised and renewed according to the " norm of the fathers ", namely not " in one fell swoop ”, but in two steps, namely 1965 and 1969/70.

Within the just mentioned Consilium , the work of Coetus X on the celebration of Mass under the direction of Johannes Wagner was to become particularly significant. It also included: Anton Hänggi , Mario Righetti , Theodor Schnitzler , Pierre Jounel , Cipriano Vagaggini , Adalbert Franquesa , Pierre-Marie Gy and Josef Andreas Jungmann . As a “fraternal and peaceful gesture”, non-Catholic liturgical scholars of other denominations also took part as observers in the deliberations of the Consilium ; these were: Ronald Jasper , Massey H. Shepherd , A. Raymond George , Friedrich-Wilhelm Künneth , Eugene L. Brand , Max Thurian .

On January 27, 1965, while the Council was still in progress, the Consilium and the Congregation of Rites jointly published a significantly revised official ordinance as a replacement for the previous version in the Roman Missal of 1962: Ritus servandus in celebratione missae and Ordo missae , which contain the corresponding parts of the missal John XXIII from 1962 legally replaced:

- Ordo Missae. Rite servandus in celebratione Missae. De defectibus in celebratione Missae occurentibus. Editio typica. Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis 1965.

The reorganization ("1965 rite") removed the celebration of the opening and the liturgical service from the altar, and allowed u. a. the use of the vernacular for the first time, from which prayer was initially excluded until 1967 , and it was generally free for priests to celebrate the Eucharist facing the congregation ( versus populum ).

Conservative observers assumed that the reform status reached in 1965 fulfilled the will of the Council constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium .

“The peculiarity and core point of this revision is the completed connection to the liturgy constitution of the council. The translation, taken from the Latin-German altar log, facilitates the common celebration of the liturgy in the mother tongue and promotes the actuosa participatio of the faithful. The theological and liturgical introductions, such as the references to contemplative prayer and the right reception of the sacrament of penance, also correspond to the spirit of the constitution. "

Comparative comparison of the Missal from 1962 and 1965

→ Main article: List of changes to the Ordo Missae due to the liturgical reform

Second stage of the implementation of the Council's resolutions after 1965: The “Second” Roman Missal

After 1965 the following instructions were given :

- Instruction Tres abhinc annos of May 4, 1967 for the proper implementation of the Constitutional Council on the Sacred Liturgy Sacrosanctum concilium

- Instruction Memoriale Domini dated May 29, 1969 on how to give communion

- Instruction Liturgicae instaurationes of September 5, 1970 for the proper implementation of the Constitutional Council on the sacred liturgy Sacrosanctum concilium

- Instruction Varietates Legimae of January 25, 1994 on the proper implementation of the Constitutional Council on the Sacred Liturgy Sacrosanctum concilium No. 37-40

- Instruction Liturgiam authenticam of March 28, 2001 on Article 36

Missale Romanum from 1969

In preparation for further reforms of the liturgy, Coetus X of the Consilium, under the direction of Johannes Wagner, had presented his proposals and drafts in a Missa normativa until 1967 . This was shown to the assembled bishops for the first time in the Sistine Chapel on October 24, 1967 as part of the First Synod of Bishops from September 29 to October 29, 1967, and they were asked for their opinion on individual points.

With the Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum of April 3, 1969, Pope Paul VI. a new edition of the Latin Ordo Missae and the Institutio Generalis Missalis Romani (= replacement of the earlier rite servandus in celebratione missae ) in force (for details see parish fair ).

Pope Paul VI declared:

“Nostra haec autem statuta et praescripta nunc et in posterum firma et efficacia esse et fore volumus, non obstantibus, quatenus opus sit, Constitutionibus et Ordinationibus Apostolicis a Decessoribus Nostris editis, ceterisque praescriptionibus etiam peculiari mentione et derogatione dignis”.

"Our orders and regulations should be valid and legally binding now and in the future, with the repeal of any conflicting constitutions and ordinances of our predecessors as well as all other instructions of whatever kind."

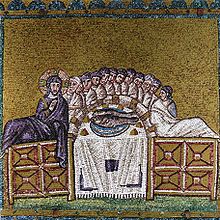

Only three days later, Benno Gut and Ferdinand Antonelli put the Congregation of Rites into effect with the decree of April 6, 1969 (Prot. No. 22/969), the General Introduction to the Roman Missal (Institutio generalis Missalis Romani) . It replaced the previous Rubricae generales , the rite servandus in celebratione and the rite servandus in concelebratione as well as De defectibus in celebratione Missae occurrentibus . Her Art. 7 clearly defined the mass as a collective act:

“Cena dominica sive Missa est sacra synaxis seu congregatio populi Dei in unum convenientis, sacerdote præside, ad memoriale Domini celebrandum.”

"The Lord's Supper - the mass - is the holy synaxis or gathering of the people of God who come together to celebrate the memory of the Lord under the direction of the priest."

This definition was remarkable in several respects and formed the theological core that formed in many details of the new Missal. On the one hand, the mass was not defined as a mass offering , but initially as a cena, i.e. as a meal; furthermore, it was not the mass that was holy but the assembly; ultimately it was not a sacrifice of the priest, but a celebration of the community under the direction of the priest. This interpretation of the council and the liturgical reform, advocated by both “traditionalist” and “progressive”, as a “break” with the previous understanding of measurement is shown in a statement on “progress [of the reform] in detail” by the Münster liturgical scholar and consultor Emil Joseph Lengeling shortly after the missal was introduced in Germany in 1975:

“From the general introduction to the missal of 1969, the ecumenically viable sacramental theology of the celebration of the Mass, which was already emerging in the liturgy constitution (47) and in the Eucharist instruction (1967), should be emphasized. Despite the new version of 1970, forced by reactionary attacks and, thanks to the skill of the editors, to prevent worse things from happening, it leads - in the spirit of Odo Casel - out of the dead ends of the post-Tridentine victim theory and corresponds to the consensus that has emerged in some interdenominational documents of recent years. "

Ottaviani intervention 1969

As the Ottaviani intervention , a text entitled "Brief Critical Inquiry" of the Ordo Missae became known, which was signed with a letter of recommendation dated September 25, 1969 to Paul VI by the Cardinals Alfredo Ottaviani and Antonio Bacci . got. The Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith , Cardinal Franjo Šeper , rejected this “investigation” on November 12, 1969 as superficial and false. Paul VI added a foreword to the Missale Romanum of 1970, in which he justified that the liturgical reform was being carried out in fidelity to tradition. The renewed form of the Mass is also a sacramental, not just symbolic, memory of the Lord.

Role of Pope Paul VI.

Pope Paul VI shaped the ordinance of the Mass with great intensity - unlike Pope Pius V in 1570 - because he was very interested in liturgy and was aware of his responsibility for the church service. In addition, he intended to get back to a binding order of the mass after liturgical experiments in the years after 1965, for example in the Netherlands and Belgium, had several hundred newly written prayers. Some concrete instructions go to Pope Paul VI. own initiative, z. B. the unchanged retention of the Roman mass canon or the sign of the cross at the beginning of the mass, which places the entire celebration under the sign of Christ. In contrast to many other corrections, the liturgy commission did not find any example in the tradition; here how u. a. in interpreting the “Mysterium Fidei” (from the words of change) as a call to the people, the Pope had personally decided. In view of the criticism of the liturgical reform that had already started in 1964, the Pope emphasized in the consistory before the cardinals on May 24, 1976 that the renewed ordinance of the Mass claimed general validity in the church and should replace the older form. He claimed the same authority of a council for the new missal as Pope Pius V had done in 1570 for the Roman Missal, which was drawn up as a result of the Council of Trent.

The liturgical question in the narrower sense of whether a pope was allowed to implement a directive of the council so intensely and authoritatively is answered with unreserved approval by almost all theologians. The liturgical traditionalists - according to the Vatican estimate that is no more than 0.2 percent of the 1.1 billion Catholics - for the most part look at the missal of Pope Paul VI. as valid, even if they prefer the earlier version of the measuring regulations. Only a tiny fraction of liturgical traditionalists are also supporters of integralism .

New prayers - taking into account the Roman tradition

With the new edition of the complete Missale Romanum, which appeared on March 26, 1970, it replaced the Editio typica from 1962/65. Paul VI In addition to the only slightly changed version of the traditional Roman Mass Canon, which was now formulated as the First Prayer, allowed three new Eucharistic Prayer . The 2nd Prayer follows the concept of the Traditio Apostolica of Hippolytus of Rome (3rd century), the IV Prayer is based on an Eastern Church anaphora of Antiochene tradition. The III. Prayer reveals the contents of the Roman mass canon with special consideration of the Christocentric ecclesiology of Vatican II; it was designed by Cyprian Vagaggini OSB. The draft of a fifth prayer with an even closer approximation to the oriental anaphora, especially the Alexandrian Basil's anaphora , met with concerns at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 1967 and was therefore postponed; the other three drafts, however, were approved and officially published.

To avoid a “mixed rite”, only those new prayers were approved that corresponded to the spirit ( ingenium ) of the Roman tradition.

The Pope also edited the Words of Change by adapting their text (slightly) to the biblical tradition of the institution reports. But they must be said "the same in every prayer". In addition to the current use of living languages, the most obvious change is that the words “ Mysterium Fidei ” (“Mystery of Faith”), previously an insert in the text, have been placed after the conversion words and are designed as an introduction to an acclamation by the believers. The congregation responds with an acclamation ("Ruf"), for which the Roman Missal 2002 provides several variants, e.g. B .:

"We proclaim your death, O Lord, and we praise your resurrection until you come in glory."

The renewal was justified, among other things, by the fact that many texts, especially duplications, had been removed from the mass, new texts were formulated, old church, pre-Gothic texts were taken up again and existing texts were revised. The new edition of the Missale Romanum appeared in 1970. The reform of the mass was completed in 1975 with the permission of two further new prayers - "Reconciliation" for special occasions - and immediately thereafter implemented and accepted worldwide. Few of even the conservative clergy and lay people opposed the liturgical innovations, but vehemently. Because of this resistance, the renewed missal was implemented with the greatest papal authority in order to avoid a liturgically staged church division. In the Missale Romanum from 2000, published in 2002, the two prayers on the subject of "Reconciliation" from 1975, three prayers for masses with children and four variants for prayers at masses in special concerns (revised, formerly so-called " Swiss prayers ") integrated.

The Consilium , which oversaw the liturgical reform from 1964 to 1969, worked out criteria by which the Roman tradition differs from the liturgies of the Eastern Churches and other Western traditions (Ambrosian, Gallican, Mozarabic rites).

In particular, the new prayers to be created should, according to the Pope's wish, correspond to the “Roman genius”. The typically Roman character is preserved in particular through the one-time consecrative epics reading (calling down the Holy Spirit) immediately before the appointment report (words of change). Moving the intercessions (requests) to the second part of the new high prayers gave them a clearer line and transparency, i.e. it did not imitate the mirror-image structure of the traditional Canon Missae (Roman Mass Canon = High Prayer I).

The Second Prayer takes up the basic idea of the Prayer, which is in the tradition of Hippolytus of Rome (3rd century). It is short and was quickly accepted by the clergy because of its clear “Roman” terminology and brevity. The fourth prayer is in the Eastern Church tradition, but preserves the typically Roman scarcity of the liturgical style. The Third Prayer re-expresses the basic ideas of the Roman Mass in that it clearly emphasizes the sacrificial character of the Mass in accordance with the ecclesiology of Vatican II.

All three new prayers express the contents of the Roman rite that are less strongly expressed in the Canon Missae (High Prayer I: “Roman Mass Canon”). They thus express the entire tradition of the Church before 1570 more clearly than the Tridentine Missal Pius V had done. Joseph Ratzinger said: "The complete uniformity of its application in Catholicism was a phenomenon at most in the first half of the 20th century", namely since the entry into force of canon law in 1917.

Popular language editions of the Roman Missal:

"Liturgical Wildwuchs" and the German-language missal from 1975

The widespread introduction of vernacular languages into Catholic worship was supported by Pope Paul VI. Approved in several steps between 1964 and 1971 and supported and promoted by the Bishops' Conferences , to which the Sacrosanctum Concilium granted its own competence. For areas outside the European cultural area, the council also approved a careful inculturation of the liturgy. With reference to this, not only the instauratio (within the framework of the Roman type) of the liturgy, but also a moderate integration of non-Roman and non-Latin forms of worship in worship is possible.

When the new Missale Romanum appeared on March 26, 1970, there was still no translation from Latin into German. In the meantime, it was allowed to be used in parallel alongside the liturgy of 1962 and the altar log . In order to bridge the gap until the German-language missal was published , the German-language liturgical institutes published eight booklets in the spring of 1971 with the title Selected Study Texts for the Future German Missal . In practice, the texts were perceived as not binding, probably also because they were already outwardly different from the earlier, firmly bound formats by a simple ring binding; Therefore, a large private market with a large number of vernacular texts for the celebration of the Mass was created in parallel. Balthasar Fischer speaks of a "phase of liturgical growth". In order to push this back, the German bishops pointed out with the decree Exclusive use of authentic liturgical texts in the Eucharistic celebration in the years 1971/72 with reference to the instruction Liturgicae instaurationes that the replacement of biblical readings by secular texts and the use of non-approved Eucharistic texts Prayers are forbidden. In September 1975 the German missal was finally published .

In France, too, shortly after the council, liturgical practice went beyond its specifications, sometimes very far. Louis Bouyer , actually a great advocate and supporter of the liturgical movement , remarked sharply in 1968: “la liturgie d'hier n'était plus guère qu'un cadavre embaumé. Ce qu'on appelle liturgie aujourd'hui n'est plus guère que ce cadavre décomposé " (" the liturgy of yesterday was little more than an embalmed carcass. What is called the liturgy today is little more than a decayed carcass of it " ).

In the United States, the implementation of the Roman instructions was a little slower and it was not until April 1967 that mass could be celebrated almost entirely in English. The American bishops only excluded the prefation and the canon from this. However, until the new missal was issued , the amount of liturgical changes largely corresponded to the number of changes to which the Missal Pius V had already been subjected in the centuries before. The structure of the fair as such was largely unchanged up to this point. Until November 1971, both the so-called old mass and the Novus Ordo could be celebrated side by side in the USA.

The Catholic Church in China has a special position in the implementation of the liturgical reform . The KPV only implemented the requirements from Rome at the end of the 1980s.

Revision of the hymn books: Gotteslob 1975

The new orientation of the liturgy has also led to a further appreciation of the folk song. For this purpose, the bishops' conferences and dioceses of the German-speaking countries created a hymn book in 1975 with the praise of God , which is not only to be understood as a hymn book, but rather as a “role book” of the community. After a process of processing that took several years, the praise of God was introduced in a new form in Advent 2013.

Other liturgical books: Book of Hours and Rituals

The reform of the Missal was without a doubt by far their greatest project. However, the book of hours was also subject to extensive reform. Within the consilium , Aimé-Georges Martimort was responsible for its revision. Against Jungmann's opposition, it remained oriented towards the monastic hourly prayer. When the Latin books were translated into German, the newly created reading chamber was given a special character through the inclusion of readings by Odo Casel and Romano Guardini . Instead of the Latin hymns , it often contains adaptations (e.g. by Silja Walter , monks from Münsterschwarzach, Maria Luise Thurmair and Georg Thurmair ) and new compositions.

Although a large majority of the Council Fathers spoke out in favor of retaining the full Psalter , Paul VI, who had already rejected the curse psalms before his election as Pope, pushed through the eradication of several Psalms and several individual offensive verses by virtue of papal authority:

“The three Psalms 58 (57) , 83 (82) and 109 (108) , in which the curse character predominates, are not included in the Psalter of the Liturgy of the Hours. Individual such verses from other psalms have also been omitted, which is noted at the beginning. These text omissions were made because of certain psychological difficulties, although curse psalms occur even in the piety of the New Testament (e.g. Rev 6:10 EU ) and do not in any way aim to induce cursing. "

Since the first International Liturgical Study Meetings , it has been their special concern to better distinguish the rite of infant baptism from adult baptism . Balthasar Fischer in particular made this his business.

Comparative comparison of Missal 1962 and Missal 1975

Ordo missae

In a comparative overview, the Holy Mass between the forma extraordinaria according to the Missal Romanum John XXIII. of 1962 and the forma ordinaria after the Missale Romanum Paul VI. from 1970 or the German translation in the missal from 1975 the following overview of the most important differences:

| Roman Missal from 1962 | Missale Romanum from 1970 / Missal from 1975 | |

|---|---|---|

| Basics | ||

| Structure of the fair |

|

|

| Sacred language | Latin | Latin or vernacular |

| Direction of prayer | de facto: ad orientem ( high altar ) | de facto: ad populum (people's altar ) |

| Location of the priest | continuously at the altar | Altar , sedile , ambo |

| Liturgical vestments | de facto abolition of some items of clothing such as tunicella , manipulas, etc. | |

| Forms of the fair |

|

|

| Measurement setup in detail | ||

| Preparatory Prayer: | Opening: | |

|

||

| Pre-fair | ||

|

||

| Word worship | ||

Right side of the altar :

Left side of the altar (the so-called Gospel side) :

|

Ambo :

|

|

| Sacrificial mass | Eucharistic celebration | |

| Sacrifice preparation | Gift preparation | |

| Act of sacrifice ( change ) | Eucharistic prayer | |

|

|

|

| Sacrificial meal | Communion | |

|

|

|

| Discharge | Discharge | |

|

|

Communication theory comparison

The sociologist of religion Marc Breuer regards the forma extraordinaria or Tridentine mass and the Protestant preaching service as antithetical poles in terms of communication theory . The mass after the liturgical reform, on the other hand, occupies a middle position between the two:

| Roman Missal from 1962 | Protestant sermon service | Missal from 1975 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| information | Representation of the mystery , sacredness of the sacraments | Bible statements | Representation of the mystery, sacredness of the sacraments, statements of the Bible |

| standard | ritual coherence | textual coherence | ritual and textual coherence |

| priority form of communication | Rite (act) | Sermon ( language ) | Rite (act), explanation / sermon (language) |

primary form of inclusion:

|

Acting (demonstrating) | Speaking (reading, preaching) | Acting (demonstrating), speaking (reading, explaining) |

|

To watch (experience) | Listening (understanding) | Watching (experiencing), acting (participating), listening (understanding) |

Reform of the Liturgy of the Hours

Calendar reform

Effects of the liturgical reform: consent and ancient ritualists

Lay and clergy consent

| new shape appeals to me | 43% | |||

| shouldn't change so much | 21% | |||

| shouldn't change at all | 9% | |||

| undecided, I cannot judge | 27% | |||

| Approval of the Reformed mass celebrations among all German Catholics in 1979 | ||||

The renewed form of the Roman liturgy found general acceptance among Catholics in Germany. In a survey by the Allensbach Institute for Demoskopie for the German Bishops' Conference in 1979, about ten years after the introduction of the Latin Missal and about four years after the introduction of the German translation, a majority of 43% of all Catholics surveyed stated that they had the new Form agreed, while 21% were in favor of fewer changes and 9% in favor of no changes at all.

| new shape appeals to me | 41% | |||

| shouldn't change so much | 42% | |||

| shouldn't change at all | 10% | |||

| undecided, I cannot judge | 7% | |||

| Approval of the Reformed Mass among German Catholics who go to church every Sunday, 1979 | ||||

Approval for the reform was greater, the less the respondents attended church on Sundays; only among the regular churchgoers was the picture “completely divided” and 41% said they were satisfied with the new measuring order, while 42% rejected it and a further 9% would not have preferred any changes.

The majority of American Catholics were positive about the liturgical reform. However, it led to a clear split between opponents and supporters of the reform, which only the controversy over the encyclical Humanae Vitae is equal in severity . In a Gallup poll in 1979 and 1984, 64% and 40%, respectively, of the American Catholics surveyed were in favor of a return to the old liturgy, or at least its alternative admission. However, there is no empirical evidence that the simultaneous clear and steady decline in attending Sunday Mass in the USA can be causally attributed to the liturgical reform; only among older Catholics was the new liturgy a factor. A Galupp and NORC poll found that slightly less than 10% of all American Catholics did not attend mass more often in 1974 because of the liturgical changes.

The decrease in church attendance on Sundays in the USA can also be noted for France; the year 1965 marks the turning point here. The French historian Guillaume Cuchet and the French statistician Jérôme Fourquet see a basis for this process in the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. However, this did not act as a cause (“le concile n'a pas provoqué la rupture”), but as a trigger (“il l'a déclenchée”) . However, this relates less to the reform of the liturgy itself than to the perceived loss of the binding force of the entire Catholic practice of faith by the council within a very short time.

Old ritualists

Some critics take the view that, in a modernist tendency , the reform made the sacrificial character of the Eucharist step back in favor of a meal, although it is doubtful whether changes in the texts decreed by the Council could change the “character” of the liturgical event.

Bishop Antônio de Castro Mayer (1904–1991, excommunicated in 1988) did not introduce the renewed liturgical books of the Roman Catholic Church in his diocese of Campos (Brazil). In addition, the retired Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre rejected them for the Society of St. Pius X , founded by him .

Marcel Lefebvre and the Society of St. Pius X.

While the liturgy commission was still active, a counter-movement emerged from which traditionalist groups later formed. The Society of St. Pius X , founded in 1970 under Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre , which received the Roman Missal of Pope Paul VI , became particularly well known . refuses. Among other things, she criticized the announcement of the Congregation for Divine Services on October 28, 1974, according to which exemptions for mass celebrations "with the people" were no longer granted after the older Missal of 1962.

This disciplinary measure met resistance from traditionalist groups. These argued, among other things, that this was illegal because of Pope Pius V's Constitution Quo primum tempore , as well as punitive measures against priests who publicly read the old mass; private celebrations were easily allowed to older priests. From a misunderstood ecumenism which would make Roman Catholic Church , although concessions to Protestantism , but shows itself relentlessly against resistance from the "ranks".

On September 8, 1976, Jean Guitton asked the Pope if a liturgical concession was possible. Paul VI replied:

“En apparence cette different porte sur une subtilité. Mais cette messe dite de Saint Pie V., comme on le voit à Ecône, devient le symbole de la condamnation du Concile. Or, je n'accepterai en aucune circonstance que l'on condamne le Concile par un symbols. Si cette exception était acceptée, le Concile entier sera ébranlée. Et par voie de conséquence l'autorité apostolique du Concile. »

“At first glance, this argument is just about a small thing. But this mass, as we see it in the Ecône , known as the Mass of Saint Pius V , became the symbol of the condemnation of the Council. However, under no circumstances will I accept that the council is condemned by a symbol. If this exception is accepted, the entire council will be shaken. And with it the apostolic authority of the council. "

Paul VI was of the opinion that the dispute was about the council as such and that the "old mass" was used as a weapon against it.

After Archbishop Lefebvre's arbitrary episcopal ordinations in 1988, Archbishop Lefebvre and the newly consecrated Bishops of the Pius Brotherhood were excommunicated and the priests of the Brotherhood were suspended from their priestly functions and thus forbidden from celebrating masses and donating sacraments. The episcopal ordination was described by Pope John Paul II as a schismatic act.

Indultmessen

For the benefit of priests and believers who preferred the Tridentine rite, Pope John Paul II allowed the diocesan bishops, for pastoral reasons and under certain conditions, to give permission to celebrate according to the Roman Missal of 1962 ( Indult Mass ). Guidelines for this had already been laid down in the Quattuor abhinc annos letter of October 3, 1981. On July 2, 1988, Pope John Paul II published the Motu proprio Ecclesia Dei Adflicta in which he addressed an appeal to all those previously associated with the Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre's movement, urging them “to do their serious things To fulfill the duty to remain united with the Vicar of Christ in the unity of the Catholic Church and not to support that movement in any way ”. He offered "to all those Catholic believers who feel bound by some earlier forms of liturgy and discipline of the Latin tradition" to "make ecclesiastical communion easy for them by measures necessary to ensure that their wishes are taken into account".

Within the Catholic Church today there are about 30 groups that have received permission from the Holy See to celebrate such indult masses. The difference between these groups and the Society of St. Pius X, for example, is that the latter rejects essential results of the Second Vatican Council, above all religious freedom, ecumenism and the appreciation of the laity , and sees the Catholic faith as impaired by them. For the groups that have remained in the Roman Catholic Church or have returned to full communion with it, it is essentially about the celebration of Mass in the previously accustomed form; with regard to doctrine, they are usually ready to accept the Council documents, provided that these are interpreted according to traditional doctrine. The Motu proprio Summorum pontificum Pope Benedict XVI. of 7 July 2007 can also be seen an offer of reconciliation to those Catholics who are currently not or not fully in communion with the Holy See. The Pope was also interested in a continuous perspective, i.e. the spirit of the liturgy in general.

Summorum Pontificum and the forma extraordinaria

With Summorum Pontificum , the liturgy of 1962 was established as an extraordinary, i.e. special form of the Roman rite, but at the same time it was opened up for further development: the readings at the parish mass (Missa cum populo) may be given in the vernacular. In the future, new saints and some of the new prefations may also be added to the 1962 missal . The Good Friday intercession for the Jews contained in the 1962 Missal was approved by Pope Benedict XVI in 2008. replaced by another worded one. The extraordinary form ( forma extraordinaria ) should therefore also undergo a kind of liturgical reform, but in a different way than that for the "ordinary form" by Popes Paul VI. and John Paul II. This also proves the way in which Benedict XVI changed the intercession of the Jews in the 1962 Missal. 2008: The pre-conciliar text was abolished, but not that of Paul VI. 1970 introduced (in Latin) version of the normal form adopted, but created a new special form.

Without devaluing the results of the liturgical reform, Pope Benedict XVI. the older 1962 custom ( usus antiquior ) of the Roman rite with motu proprio of July 7, 2007 as forma extraordinaria is permitted again more broadly (cf. Summorum pontificum ). However, the usus instauratus remains the normal form ( forma ordinaria ) of the Roman liturgy.

In the Apostolic Letter Sacramentum Caritatis (2007) Pope Benedict XVI recommended greater use of Latin in mass celebrations at international events. In addition, “the faithful should be given general guidance to know the most general prayers in Latin and to sing certain parts of the liturgy in the Gregorian style ”.

Before the participants of the 68th liturgical week on August 24, 2017, Pope Francis declared on a possible further “reform of the reform”:

“Dopo questo magistero, dopo questo lungo cammino possiamo affermare con sicurezza e con autorità magisteriale che la riforma liturgica è irreversibile.”

"Following this teaching post, on this long journey, we can affirm with certain certainty and magisterial authority that the liturgical reform is irreversible."

Effects in church architecture and art

Church architecture

Was particularly visible in the Eucharist almost everywhere changed location of the priest at the altar, now in general - often at a newly constructed " people's altar " - with his face to the altar and community ( versus populum ) turned instead as before versus apsidem, to Apse . In either position, however, prayer and spirit are always directed “ad Deum” (to God) and “ad Dominum” (to the Lord).

Already Inter Oecumenici had therefore arranged in 1964 in Article 91, that the altar should be circumambulatory. The Institutio generalis Missalis Romani ordered almost word for word in Art. 262:

"Altare maius exstruatur a pariete seiunctum, ut facile circumiri et in eo celebratio versus populum peragi possit, quod expedit ubicumque possibile sit."

“The main altar is erected separately from the wall, so that one can walk around it easily and celebrate mass on it facing the community; that [the free-standing construction] is beneficial wherever it is possible. "

On the other hand, according to Art. 267, there should only be a small number of side altars:

"Altaria minora numero sint pauciora et, in novis ecclesiis, in sacellis ab ecclesiæ aula aliquomodo seiunctis collocentur."

"The side altars should be rather few and, in the case of newly built churches, be erected in side chapels that are somehow separate from the main room of the church."

This change made renovations necessary in almost all churches. The altar barriers ( communion benches ) were mostly removed. In addition, in churches built after the council, the altar was not infrequently drawn far into the center of the community and the rows of pews were arranged in a (semic) circle. This was intended to emphasize the common dignity of God's people and the closeness of the Incarnate Lord, and to facilitate the active and conscious participation of all of God's people in the liturgy.

Many new church buildings, however, went beyond these requirements and tried to make the ecclesiology of Vatican II tangible in new architectural forms. Models for this can already be found in church buildings from the 1930s, which were influenced by the liturgical movement. Instead of the old, on the high altar in the apse at the east end of the nave oriented form of church experimented with round, square and elliptical shapes in which the people of God to the centrally located altar or at the ambo as the word altar flocking . It is not uncommon for them to be central buildings in which the seating for the believers is arranged in a circle, square, polygon, etc. The 2nd Vatican had demanded “noble simplicity” (SC 34) and “noble beauty” instead of “mere effort”; many architects implemented this requirement in forms of contemporary minimalism and functionalism . The results of the remodeling of existing churches, which have been reduced to the bare minimum , were also pejoratively referred to in English-speaking countries with the suitcase word wreck-o-vation .

In the rest of sacred art, too, there was a change from the hierarchical to the “democratic church” in such a way that formerly formative devotional images of the Catholic Church were removed from the churches or at least their number was often greatly reduced. According to the political scientist Hans Maier , the subsequent implementation resulted in a wide range: from controversial unconventional projects (as with Georg Baselitz ) to successful (as with Georg Meistermann , Herbert Falken , Gerhard Richter and Neo Rauch ) cooperation between modern artists and Communities. Hans Maier points out that these post-conciliar developments have not yet been researched enough.

Church music

At the end of the 19th century, three groups of church music design could be distinguished: the chorale offices of the abbeys , the parishes under the influence of Cecilia, and those parishes in southern Germany that were in the tradition of the Viennese classic . Although the congregation sang in the vernacular during - or better: parallel to - Mass, only the Latin spoken text of the celebrant was considered liturgically effective.

The council constitution on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium , attested church music to be "a necessary and integral part of the solemn liturgy" (SC 112). The constitution was clearly oriented towards church tradition in its basic orientation and encourages the maintenance of the traditional "treasure" of church music. Corresponding to the concern of the liturgical movement for the maintenance of the Gregorian chant , it describes this as “the singing of the Roman liturgy” (SC 116) and recommends the completion of a new editio typica of the associated liturgical books. Finally, it highlights the special role of the pipe organ in church music (SC 120).