Catacombs in Rome

There are more than 60 catacombs in Rome , but only a few are open to the public. The most famous catacombs of Rome are located on the Via Appia Antica , Via Salaria and the ancient Via Labicana .

history

The formation of the catacombs in Rome is related to the development of burial culture. Since the Twelve Tables law of 450 BC It was imperative that burials were only allowed outside the city walls. In ancient Rome , there was next to the burial also from the Hellenistic adopted cremation in urns . The first Christian communities in Rome adhered to the body burial because they viewed the tomb as the place of the future resurrection . In the 1st century the Christian parishioners had buried their dead in the public pagan cemeteries outside the Aurelian city wall . In the 2nd century, Christians adopted the Jewish custom of burying their dead in catacombs. So far, six Jewish catacombs ( Catacombe Ebraiche ) have been rediscovered. For the underground burial places it was legally stipulated that they were not allowed to cross the boundaries of the above-ground area; therefore one was forced to lay out the tombs occupied by tombs on several floors, which was made easier by the texture of the tuff rock.

By edict of 257, Emperor Valerian forbade Christians from practicing their cult in public and from entering their above-ground cemeteries, which meant that burials had to concentrate on underground tombs. These underground Christian cemeteries were then called cryptae ( crypta = Latin cave, underground vault). The name "catacomb" was first widely used in the 9th century. This expression goes back to the Roman field name ad catacumbas (from Greek κατά κύμβας = "near the caves"), which had become common for the Sebastian catacomb on the Via Appia because this catacomb was near the hollows and hollows of a pit for pozzolan soil lay; this designation was then added to the name of the local basilica in the 8th century as 'San Sebastiano ad catacumbas'. After most of the catacombs were closed in the 9th century, the Sebastian Catacombs remained accessible and continued to be visited, which led to the adoption of this name for all catacombs; since then 'catacomb' has been the archaeological term for underground burial sites.

Even with the oldest catacombs it has been established that they were planned for a large expansion and efficient use on several floors and that the corridors, laid out according to a geometric scheme, were designed for a later expansion. Vertically arranged burial niches were uniform pattern in the wall surfaces of the passages ( Loculusgrab from loculus = small space) are incorporated; because they were carved into the wall very close to one another and one above the other, they were also referred to as columbarium (Latin columbarium = dovecote). Later there were vaulted wall niches ( Arkosolium , from arcus = arch and solium = grave) as well as burial chambers ( cubiculum = bedroom) set up in junctions from the main corridors , which were intended for privileged burials with more elaborate graves (with sarcophagi and rich decoration). The uniformly designed Loculus graves, arranged one above the other, were closed with marble or brick slabs and were occupied several times. The inscriptions on the grave slabs and on the walls only contained names and Christian symbols , in accordance with the concept of equality of the new religion . The names of the first catacombs mostly go back to the property owners or the founders of the first underground burial places (e.g. Domitilla, Priscilla, Commodilla), who came from some noble families who converted to Christianity at an early age; other names have their roots in place names or in the proper names of the martyrs buried there.

The administration and control of the catacombs was the responsibility of the Bishop of Rome very early on , represented by the deacon of the respective ecclesiastical region. The extensive excavation work for the catacombs as well as the laying of the graves and the burials were carried out by the fossores (grave diggers); these were skilled workers who had also been part of the church hierarchy since the 4th century . By the 5th century, the existing catacombs were expanded and, in isolated cases, new underground cemeteries were created.

Because martyrs , bishops and popes were also buried in the catacombs , special places were created there for the veneration of saints with services and for meetings to commemorate the dead with the traditional funeral meal ( refrigerium , Latin for "cooling down" as an intermediate state of the blissful lingering of the deceased), an originally pagan one and also Jewish custom, which the church tolerated as a charitable institution agape (from the Greek ἀγάπη = love, love meal) up to the 5th century .

Pope Damasus (366–384) had the martyrs' tombs in the catacombs expanded and highlighted with architectural means. This created larger rooms with marble cladding, flooring and light shafts, but also with fountains, seating and small tables ( mensae ) for the food offerings for the benefit of the deceased and for the food supplies for the participants at the funeral meal. Damasus himself also wrote more than sixty metric inscriptions for the city's martyrs, which were carved into large marble tablets and placed above the tombs. In this way the exemplary life of the martyrs should be remembered and the veneration of the oldest witnesses of the faith of the Christian community should be promoted; Damasus was also keen to restore the unity of faith - after the previous dangers of division ( Arianism ).

In the sack of Rome (410) by the Visigoths many catacombs were destroyed. Because the pilgrimages and pilgrimages to the catacombs with their graves of martyrs and saints had increased, the tours to the most important burial sites ( itinera ad sanctos ) laid out in the 4th century were restored. Signs of the intensive visit to the martyrs' graves are the hundreds of graffiti that were carved by the believers in the rooms around the graves and in the entrances. At the beginning of the 6th century, some underground rooms were expanded so that the altar for the celebration of the Eucharist could be placed directly above a martyr's grave ( ad corpus ). As a further development of this tradition, so-called catacomb basilicas were later built, the roofs of which protruded from the ground, for example the basilica Santi Nereo e Achilleo in the Domitilla catacomb.

After the wars of the 6th century and especially after the raids of the Lombards (middle of the 8th century), the tombs in the catacombs began to deteriorate because they could no longer be secured outside the city walls. In addition, new laws allowed burials within the urban area. In the 8th and 9th centuries, the popes systematically had the relics of the martyrs transferred from the catacombs to the churches within the city walls. In the Middle Ages, only the few catacombs associated with the basilicas of the Martyrs (S. Sebastiano, S. Agnese and S. Lorenzo) remained accessible. It was not until the 16th century that the rediscovery and systematic research of the Roman catacombs began, especially by the catacomb researcher Antonio Bosio (1575–1629) and the archaeologist Gian Battista de Rossi (1822–1894).

Today the Roman catacombs are among the best preserved archaeological complexes in the ancient world. The more than sixty catacombs that have been explored so far spread with their corridors over a length of several hundred kilometers in the underground of the metropolis of Rome. Of this, around 170 km with around 750,000 graves have been uncovered, including around 50 martyrs' graves. The Pontifical Commission for Sacred Archeology ( Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra ), founded in 1852, is responsible for the development, research, security and maintenance of the catacombs .

Decoration of the catacombs

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries there were only sparse grave decorations, few inscriptions and no paintings. Many niche graves were decorated with the favorite objects of the deceased, e.g. B. with pieces of jewelery, shells, bronze coins, small terracotta figures, glass ampoules or gold glass floors that were embedded in the mortar. They probably also served to find the grave again. The first inscriptions on the grave slabs only contained names and sometimes a symbol, but initially no data.

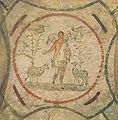

Later, both the areas between the niche graves in the long corridors and the arcosol graves as well as the walls and vaults of the burial chambers were decorated with wall paintings. In the beginning, a decoration system made up of geometric figures and tendrils was used. Later wall and ceiling surfaces were completely covered with frescoes : in the lowest zone with gates, barriers, garden views or views of a neutral beyond; in the central zone, imitations of architecture or depictions of the activities of those buried there; Biblical scenes or pictures of theophany were reserved for the apse and ceiling . The themes of the painting developed gradually from neutral or pagan motifs to a Christian repertoire. Fabrizio Bisconti has described the development and themes of Roman catacomb painting in detail.

Christian inscriptions

More than 40,000 inscriptions have been uncovered and secured in the catacombs of Rome; most of them date from the 3rd to 5th centuries and have a very heterogeneous content. Publication by the Pontifical Institute for Christian Archeology is planned in the collection of the Inscriptiones Christianae Urbis Romae septimo saeculo antiquiores (ICUR); Danilo Mazzoleni has published details.

Christian inscriptions have been found since the beginning of the 3rd century, initially only consisting of the name of the deceased, in some cases also with a Christian symbol, e.g. B. anchor , fish , dove or Christ monogram . The material consisted of marble slabs or bricks, in which the letters as capitals ( Capitalis monumentalis were carved) or scratched. Among the thousands of names, many were from pagan mythology ( Achilles , Asclepiodotus , Hercules , Hermes ); others were of Greek or Latin origin. Biblical names (Maria, Susanna, Johannes, Peter, Joseph) were not found very often; Names associated with Christian terms were more common ( Agape = love, Irene = peace, Benedictus = blessed, Renatus = born again, Theodorus = gift of God). There were also names that expressed wishes, contained names of months and place names or were derived from animal names; after all, there were nicknames and nicknames too. From the middle of the 4th century, professions were also specified, namely with the job titles or with professional characteristics (barrel, scales, ax, hammer, compass, scissors, spindle, musical instrument).

There were also monograms and letter combinations, including alpha and omega ( Α and Ω ) as well as the various Christ monograms: cross with Rho loop or cross with the Greek initials of Christ ( X = Chi and P = Rho or the complete Christogram ΙΣ ΧΣ = Ι HΣΟΥ Σ Χ ΡΙΣΤῸ Σ = Jesus Christ). In addition, the early Christians used the Greek word for fish ( Ι-Χ-Θ-Υ-Σ ) as an acronym to discreetly express their membership of the Christian community; it stood for I ησοῦς - Χ ριστός - Θ εού Υ ιός - Σ ωτήρ = Jesus - Christ - God's Son - Savior; It was one of the oldest secret symbols and identifying marks among Christians, as well as the earliest and shortest form of the Christian creed . The abbreviation 'fish' was sometimes used. a. found in the Sebastian catacomb, in a burial niche in the middle of the three Roman burial houses under the right aisle of the basilica of San Sebastiano fuori le mura. The fish was seen as a symbol of a Christian's calling to fish for men (Mt 4:19).

Private monograms were rare and in individual cases they are difficult to assign. Greek was used as the language until the middle of the 4th century; it was the official liturgical language and the second official language in Rome . Particularly noteworthy are the numerous poems ( carmina ) written by Pope Damasus (366–384 ) for saints and martyrs in the catacombs. Best known is his epigram for the 'Crypt of the Popes' in the Catacomb of Calixtus. The letters carved by the Roman calligrapher Furius Dionysius Filocalus in a special script and carefully arranged have made these grave slabs the most beautiful inscription slabs.

Numerous graffiti have been found in the corridors and burial chambers of the catacombs, which had been scratched into the plaster or red tuff with pencils. They include u. a. the names of the visitors (as a sign of 'I was here'), but also references to the martyrs buried there as well as requests and blessings. The oldest graffiti are in the Memoria Apostolorum under the Basilica of San Sebastiano fuori le mura; the youngest date from the beginning of the 9th century.

The most famous catacombs in Rome

Catacombs were built along the consular streets. Currently only six catacombs are generally accessible:

- In the south of the city near the Via Appia: Catacomb of Sebastian, Catacomb of Calixtus and Catacomb of Domitilla,

- in the east the catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter on the Via Labicana (today Via Casilina),

- in the north the Agnes catacomb on Via Nomentana and the Priscilla catacomb on Via Salaria.

Sebastian Catacomb

The catacomb is on the Via Appia Antica, about two kilometers outside the city gate Porta San Sebastiano ; since 317 it has been covered with the basilica of San Sebastiano fuori le mura . After the local name ad catacumbas (from Greek κατά κύμβας = "near the hollows"), the catacomb was originally called ad catacumbas because it was located in the hollows and hollows of a pit for pozzolan soil . After the burial of the martyr Sebastian (around 288) it was then called Catacombe San Sebastiano.

The first tunnels of this catacomb were laid in the tunnel of the disused pit as early as the end of the 1st century, so that pagan and Christian burials in wall niche graves could be carried out there. In the period that followed, the catacomb expanded to four floors (now largely destroyed). There were also burial houses and small mausoleums as well as a memorial site for the apostles Peter and Paul ( Memoria Apostolorum ) around 260 . It was created after Emperor Valerian had ordered in 257 that Christians were no longer allowed to practice their cult in public and that they could therefore no longer meet at the tomb of St. Peter and St. Paul . Therefore, the common cult was moved to the underground cemetery ( cymeterium catacumbas ) on the Via Appia in the newly built Memoria Apostolorum . The trapezoidal memorial complex (23 × 18 m) consisted of an inner courtyard with two covered loggias , between which a staircase led down to a spring. The eastern loggia used by the Christians, called triclia , was slightly elevated and had wall paintings depicting flowers and animals, as well as numerous graffiti with invocations of the apostles Peter and Paul. In the middle of the 4th century, the crypt of the martyr Sebastian was laid out as an extension of a catacomb passage where the bones of the saint, who was executed around 288, were buried. In addition, the relics of the martyr Quirinus of Siscia ( Pannonia ), which are said to have been brought to Rome by pilgrims in the 5th century, are kept in the Sebastian catacomb .

Wall paintings were mainly preserved on the second floor (Moses knocks water out of the rock, a woman in an ornamental position and the baby Jesus in the manger). The three Roman tombs of the 2nd century, called Marcus Clodius Hermes , Innocentores and Beil-Mausoleum , located under the right aisle of the basilica and taken over by the Christians at the beginning of the 3rd century, were also decorated with wall paintings. On the outer front of the burial chamber of Marcus Clodius Hermes, the probably oldest wall paintings with biblical themes have been preserved (around 230): On the left, two shepherds with their flock and a third with a sheep on their shoulder; to the right, four table parties and servants with bread baskets arranged in a semicircle; in the bend in the wall a herd of pigs rushing towards a lake. These paintings are interpreted as biblical depictions of the Good Shepherd (Greek ὁ ποιμὴν ὁ καλός), the miracle of the multiplication of bread (Mt 15,32ff.) And the healing of the possessed of Gerasa, whose demons take refuge in pigs and drown with them in the lake (Mk 5.1 ff.). In addition, around 600 inscriptions have been found in the corridors and burial chambers.

Catacomb of Calixtus

The Catacomb of Calixtus is located between Via Appia Antica, Via Ardeatina and Vicolo delle Sette Chiese. At the end of the 2nd century it was the first catacomb intended only for the Christian community in Rome; it developed into one of the largest underground burial systems in Rome: under an area of approx. 15 hectares, underground passages of around 20 km with at least 370,000 graves (not including the relocations) run on up to five levels, including an estimated 100 graves of martyrs and 16 of bishops; there are also 63 family graves and crypts.

The catacomb got its name from the bishop of Rome Calixt I († 222), who was already involved in the administration of the catacomb as a young deacon and who, as bishop of Rome, also had it expanded.

The oldest parts of the catacomb include the crypt of Cecilia of Rome (around 200–230) and the so-called crypts of Lucina (around 210–305) with murals from the 3rd century ( Daniel in the lions' den , Christ as Good Shepherd, Jonas- Cycle , adorers and the Eucharistic fish). Also the 'Crypt of the Popes' with the tombs of nine Roman and three African bishops of the 3rd century; on the back wall of this crypt is the marble tablet with the praise of Damasus I, in which he praises the martyrs and bishops buried there. In the burial zone, known as the 'Sacrament Chapel', there are wall paintings from the first half of the 3rd century with motifs from the Old Testament and the New Testament (spring miracle in the desert, Jonas cycle, meal of the seven young men at the Sea of Galilee, healing of a paralyzed man , Baptism of Jesus , sacrifice of Isaac and a Eucharistic Supper with seven diners). In the 'Cubiculum of the Five Saints' (3rd century) named women and men are depicted as ornaments in a paradise garden (Greek παράδεισος = Paradeisos = garden, paradise). In the cubiculum of the deacon Severus (around 304) an inscription has been preserved in which the bishop of Rome is referred to as pope ( papa ) for the first time . In the more than 2000 inscriptions there are e.g. T. Age information and descriptions of the activities of the deceased.

Domitilla catacomb

Not far from the Calixtus Catacomb are the Domitilla Catacombs (Catacombe di Santa Domitilla) on Via delle Sette Chiese 280 ; With their approx. 17 km long galleries and around 150,000 burials, they are among the largest catacombs in Rome. According to tradition, the Christian Flavia Domitilla from the imperial family of the Flavians made it possible for her freedmen to be buried on their lands in the south of the city as early as the end of the 1st century, from which a Christian catacomb arose in the second half of the 2nd century, which was named Domitilla received.

The martyrs Nereus and Achilles were buried in a cubiculum on the second level at the beginning of the 4th century , in whose honor Damasus I had a memoria with a plaque built. Under Bishop Simplicius (498–514) the catacomb basilica SS. Nereo e Achilleo with the altar directly above the martyrs' graves ( basilica ad corpus ) was built here; the building, half above ground today, is a reconstruction of the 19th century.

In the almost 80 grave rooms and on the walls of the corridors, numerous wall paintings have been preserved that offer a good cross-section of the history of the development of Christian painting: symbols of life and resurrection from the early days, the scene of Daniel in the lions' den, one of the earliest Representations of the Good Shepherd, an enthroned Madonna, the wise men from the Orient. The painting of an arcosolium near the Ampliatus crypt, in which Christ is represented as a teacher among the apostles, dates from the middle of the 4th century.

The name of the Domitilla Catacombs is associated with the Catacomb Pact, which was concluded there on November 16, 1965, a few weeks before the end of the Second Vatican Council , and to which more than 500 bishops around the world have joined to date. All signatories have committed themselves to a simple lifestyle and service to the poor, as well as renouncing pomp and titles.

Priscilla Catacomb

The Priscilla Catacomb (Catacombe di Priscilla) is located on Via Salaria near the Villa Ada Park . On two levels, each laid out in a herringbone pattern, there are around 40,000 graves in 13 km long corridors. These early Christian burial chambers were discovered by chance in 1578 during viticulture work.

Towards the end of the 1st century, the senatorial family of the Acilians owned their hypogeum (Greek hypógeion , hypo = under and gẽ = earth), an underground tomb in which the inscription Priscilla clarissima was found, an indication that this Priscilla belongs to the family belonged to the Acilier. Then at the beginning of the 3rd century the Christians had laid underground passages for their burials in the neighboring former pit, and the name Priscilla was adopted for this catacomb on Via Salaria. More than 20 large niche graves and many hundreds of wall graves were created. There was also the Cappella Graeca - named after the Greek inscriptions found - with wall paintings from the second half of the 2nd century: Madonna with Child and Prophet Balaam under the star of Bethlehem (oldest depiction of this motif), Adoration of the Kings , the three young men in the fiery furnace, Moses knocks water out of the rock , story of Susanna in the bath , phoenix (as a symbol of the resurrection ); also in the second yoke above the apse niche the Eucharistic Supper . Some time later, some depictions of this woman buried here were made in the Cubiculum of Velatio (end of the 3rd century), as well as the sacrifice of Isaac and the three young men in the fiery furnace (here next to a dove with a branch in its beak as an indication of divine intervention). Pope Silvester , who died on December 31, 335 , was buried here, as well as six other popes and more than ten martyrs.

Marcellinus and Peter catacomb

On the ancient Via Labicana, today's Via Casilina, the cemetery of the imperial bodyguard ( equites singulares ) was located on the imperial property ad duos lauros (“near the two laurel trees”) in pre-Constantine times . In the immediate vicinity of this equestrian cemetery, a Christian catacomb was built in the second half of the 3rd century, in which many martyrs were buried as victims of the persecution of Christians under Emperor Diocletian (around 304), including the particularly venerated Petrus exorcista and Marcellinus presbyter , after whom one later named the catacomb; also buried there were: Tiburtius, Gorgonius of Rome , the Quatuor coronati and other nameless martyrs.

Because the Imperial Life Guard fought on the side of its rival Maxentius in the battle of the Milvian Bridge , it was dissolved by Emperor Constantine and the cemetery was closed. Instead, around 315, Constantine had a basilica built on this site in memory of the martyrs Peter and Marcellinus and the other victims of the persecution of Christians who were buried in the catacomb. Under Pope Damasus I (366–384) the catacomb was expanded and decorated, especially the crypts of the titular saints and the martyrs Tiburtius and Gorgonius . Further remodeling followed until the middle of the 6th century. Today the corridors are up to 16 meters deep and extend over an area of 18,000 m² with an estimated 15,000 burials. After many years of restoration work, the underground facilities and the valuable wall paintings were made accessible to the public again in February 2016.

The wall paintings of the catacomb with motifs from the Old and New Testament date mainly from the 2nd to 4th centuries. Notable among them are: the story of the prophet Jonas with the Good Shepherd in the middle; Noah bowing out of the ark in anticipation of the dove with the olive branch; Healing of the fluids, which is healed by touching the robe of Jesus; Daniel in the lions' den as a young prophet in ornamental posture; in the cubiculum of the seasons: Noah's ark, the miracle of the spring of Moses, the story of Job, the multiplication of loaves and fish; Baptism of Christ (with the dove of the Holy Spirit and the still visible hand of John the Baptist ); Adam and Eve after the fall; Ceiling painting in the crypt of the titular saint: Christ (with aureole ) on a throne (with cushion and suppedaneum ) between Paul and Peter, including the martyrs Gorgonius, Peter, Marcellinus and Tiburtius in adoration of the divine Lamb who is on the mountain with the four rivers stands in the garden of Eden .

Agnes catacomb

The Agnes catacomb on the Via Nomentana existed as early as the 3rd century. It became known in Constantinian times because the venerated martyr Agnes of Rome was buried there at the end of the 3rd or beginning of the 4th century , after whom the catacomb was named. The underground passages are about 10 km long on three levels, but only a small part is accessible. In specialist literature, the catacomb is divided into 3 areas: The oldest region north of today's basilica was probably built at the beginning of the 3rd century, the second east of the apse of the basilica in the 3rd / 4th century. Century and the third between basilica and mausoleum in the 4th / 5th centuries. Century. No wall paintings were found in this catacomb, but there were numerous inscriptions and graffiti.

Various structures were erected above the underground cemetery: the basilica Sant'Agnese ( coemeterium Agnetis = funeral basilica ) donated by Constantina (daughter of Constantine the Great) around 337 with its mausoleum built on the south side , now known as Santa Costanza , and the gallery basilica from around 630 Sant'Agnese fuori le mura , the so-called (Honorius building).

See also

- Replica of an early Christian catacomb in Valkenburg aan de Geul , s. Roman catacomb Valkenburg

- Catacomb saint

literature

- Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti, Danilo Mazzoleni: Rome's Christian Catacombs. History - world of images - inscriptions . Regensburg 2000.

- Fabricio Mancinelli: Roman catacombs and early Christianity . Florence 2004.

- Giovanni Battista de Rossi : La Roma sotterranea cristiana . 5 volumes. Rome 1864-1880. (Digitized version)

- Joseph Wilpert : The paintings of the catacombs of Rome . 2 volumes. Herder, Freiburg 1903.

- CB: A walk through the Roman underworld . In: The Gazebo . Issue 13, 1866, pp. 197–200 ( full text [ Wikisource ] - with illustration).

Web links

- Catacombs in Rome (multilingual)

- italia.it addresses, bus / metro, opening times

- santimarcellinoepietro.it Photo gallery of the Marcellinus and Peter catacombs

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti, Danilo Mazzoleni: Rome's Christian catacombs. History - world of images - inscriptions . Regensburg 2000, p. 13 ff.

- ↑ Hugo brewing ends castle in: Encyclopedia of Theology and Church (LThK). Freiburg 2006, Volume 2, Col. 1249 ff.

- ↑ Hugo brewing ends castle in: Encyclopedia of Theology and Church (LThK). Freiburg 2006, Volume 5, Col. 1293.

- ↑ Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti, Danilo Mazzoleni: Rome's Christian catacombs. History - world of images - inscriptions . Regensburg 2000, p. 9 ff.

- ^ Hugo Brandenburg: The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century. Regensburg 2013, pp. 259f. and 319.

- ↑ Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti, Danilo Mazzoleni: Rome's Christian catacombs. History - world of images - inscriptions . Regensburg 2000, pp. 60ff.

- ↑ Homepage of the Vatican

- ↑ Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti, Danilo Mazzoleni: Rome's Christian catacombs. History - world of images - inscriptions . Regensburg 2000, pp. 71–145 (with well-chosen images)

- ↑ Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti, Danilo Mazzoleni: Rome's Christian catacombs. History - world of images - inscriptions . Regensburg 2000, pp. 146-185.

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - A Vademecum . Freiburg, 2nd edition 2017, p. 85.

- ^ Pontifica commissione di archeologia sacra (ed.): Catacombe di Roma - San Sebastiano . Vatican City 1990, ISBN 88-7228-085-0 .

- ^ Fabricio Mancinelli: Roman catacombs and early Christianity . Florence 2004, p. 17 ff.

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - A Vademecum. 2nd Edition. Freiburg 2017, p. 84 f.

- ↑ Antonio Baruffa: The Catacombs of San Callisto - History, Archeology, Faith . Vatican City 1996.

- ↑ Umberto Maria Fasola: The Domitilla catacomb and the basilica of the martyrs Nereus and Achilles. Città del Vaticano 1989.

- ^ Fabricio Mancinelli: Roman catacombs and early Christianity. Florence 2004, p. 25ff.

- ↑ Sebastian Pittl: The catacomb pact - the forgotten legacy of Vatican II . Catholic Academic Association of the Archdiocese of Vienna

- ↑ Victor Schultze: The catacombs. ISBN 978-3-942382-79-3 , p. 1, accessed on May 30, 2011.

- ^ Fabricio Mancinelli: Roman catacombs and early Christianity. Florence 2004, p. 28f.

- ↑ Johannes Georg Deckers, Hans Reinhard Seliger, Gabriele Mietke: The catacomb "Santi Marcellino e Pietro". Repertory of Paintings . Pontificio Istitutio di Archaeologia Christiana. Città del Vaticano / Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Münster 1987.

- ^ Fabricio Mancinelli: Roman catacombs and early Christianity. Florence 2004, p. 39ff.

- ↑ Joseph Wilpert: A Cycle of Christological Paintings: From the Catacomb of Saints Peter and Marcellinus (Herder, Freiburg 1891), Kessinger Legacy Reprints, 2010.

- ^ Fabricio Mancinelli: Roman catacombs and early Christianity. Florence 2004, p. 49ff.

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - A Vademecum. 2nd Edition. Freiburg 2017, p. 88 ff.

- ^ Hugo Brandenburg: The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century. Regensburg 2013, p. 266 ff.