Colloquial Basilica

The basilica is usually a three-aisled pillar basilica, the side aisles run semicircularly around the central nave, while the central nave is kept open by pillar arcades to the passage in the aisles. This design was common in Rome for the so-called Coemeterialbasilika (funeral basilica ), which primarily served as a tomb, but in which, in addition to the celebration of the Eucharist, one also commemorated the martyrs and the dead of the community. In the period after 315 Constantine I and the imperial family erected basilicas (ital .: 'basilica circiforme' or 'basilica a deambulatorio') over the graves of some martyrs buried outside the city walls in order to be as close as possible to the saints as their advocates to be buried ( retro sanctos "with the saints"). This resulted in a special form of early Christian church building that can only be found in Rome and only within the period between 315 and the end of the 4th century.

Location and patronage

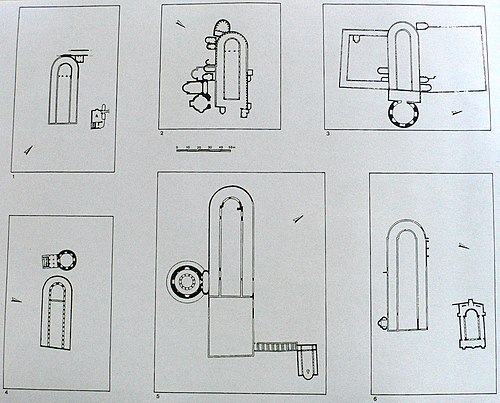

The six basilicas or coemeterial basilicas, which have been rediscovered to this day, were all on imperial property and are all on the major arteries outside the Aurelian city wall , on the east side of the city (from northeast to south):

- Via Nomentana with the Basilica of Sant'Agnese (Sant'Agnese fuori le mura) (No. 5)

- Via Tiburtina with the Basilica maior (Saint Lawrence Outside the Walls) (No. 6)

- Via Praenestina with the basilica at Tor de'Schiavi (No. 2)

- Via Labicana with the Basilica Santi Marcellino e Pietro (No. 1)

- Via Appia with the Basilica Apostolorum (San Sebastiano fuori le mura) (No. 3)

- Via Ardeatina with the anonymous basilica there (San Marco) (No. 4).

The chronological order for the establishment of these basilicas is assessed differently in research. It seems reasonable to assume the following order:

- Communal basilica Santi Marcellino e Pietro , around 315–317, size: approx. 65 m × 29 m

- Communal basilica at Tor de'Schiavi, between 315 and 320, size: approx. 66 m × 24 m

- Basilica Apostolorum , around 317-320, size: approx. 73 m × 30 m

- Communal basilica on Via Ardeatina , around 336, size: approx. 66 m × 28 m

- Basilica of Sant'Agnese, around 337, size: approx. 98 m × 40 m

- Basilica maior , between 337 and 351, size: approx. 98.6 m × 35.5 m.

Descriptions of the six basilicas can be found among others. a. with Hugo Brandenburg and Wehrens.

The basilicas were built next to or above a martyr's grave or a catacomb . These early Christian burial basilicas, donated or sponsored by the emperor and his family, formed an urban counterbalance to the numerous pagan places of worship within the city and also outside the walls.

Around these churches larger or smaller mausoleums were built, in which the imperial family, who had become Christian, also participated. The Helena mausoleum (exterior) and the lavishly furnished mausoleum of Constantina, both circular buildings based on ancient models , have been partially preserved .

Since the 6th century in Rome began to move the bones of the martyrs from the churches and catacombs outside the city walls to the secured inner-city churches, there was no longer any need to build communal basilicas. In addition, after the imperial support no longer existed, the maintenance expenditure was probably no longer acceptable. After all, liturgical needs had also changed by the 5th century.

In most cases, the patron saints of the basilicas indicate the martyrs buried and venerated there.

Design

The ambulatory basilica is a three-aisled basilica , the lower aisles of which form a passage on a U-shaped floor plan around the apse of the central nave , while the wider and higher central nave is closed off by arcades arranged in a semicircle . The surrounding aisles were separated from the nave by pillars with arched arcades. These church buildings were oriented roughly to the west, as far as the terrain permitted. The façade in the east was slightly bevelled in almost all the basilicas, although the reason for this deviation from the norm is not known. The roof probably consisted of a rafter roof .

With the exception of the two most recent basilicas (Sant'Agnese and Basilica maior ), the (inner) apse adjoined the central nave arcades, while the apse of the two buildings mentioned was slightly offset inwards ("retracted apse"). The masonry usually consisted of alternating layers of tuff and bricks ( opus listatum ).

The buildings served as burial churches. Because the entire floor area was covered with graves, they practically formed a roofed community cemetery ( coemeterium subteglatum ). The Eucharist was celebrated at the altar in the central nave and the venerated martyrs and the deceased relatives buried in the church were remembered, also through processions through the surrounding aisles. There is no reliable information about the course of the funeral celebrations and the liturgy . All that is certain is that on the occasion of the commemoration ceremonies at the graves of the martyrs for their deceased relatives and for themselves, the faithful invoked the intercession of the martyrs and prayed to God; In doing so, they are also thought of their own mortality and have kept their hope for an afterlife alive.

Model of the Basilica Apostolorum San Sebastiano fuori le mura

Architectural history

The architectural historian Richard Krautheimer has suggested that the shape of these buildings was particularly suitable for the holding of sacrificial feasts, which were held in ancient times at funerals and for the annual commemoration of the dead. That would be another explanation for why they subsequently disappeared so quickly. The fact is that this design remained without a direct successor. Only in Upper Egypt are the remains of three- or five-aisled basilicas from the 4th to 6th centuries, such as the southeast church of Kellis (today Ismant al-Ġarāb) in the Dachla oasis and the north basilica of Abu Mena . At the specified time, this type of building even represented the standard of Upper Egyptian Coptic church construction .

The six basilicas in Rome are of particular importance as cult buildings of the Constantinian era : They served the cult of martyrs and the cult of the dead of the faithful buried there, including in particular the donors from the imperial family who were buried there. Their burial in a privileged place gave this Christian cult a special status, which was apparently intended to take the place of the previously usual consecratio after the death of an emperor. The believers gathered here also took part in the memorial cult of the imperial founders. This connection between old tradition and new style is also expressed in the new design of the basilica: The shape given by the shape of the Christian community basilica is being redesigned because of the new function as a basilica with surrounding aisles and as a covered burial place and for processions.

These basilicas have the following characteristics in common:

- They were located outside the city walls on the arterial roads on the east side of Rome, on imperial property.

- They were created in the 4th century with imperial sponsorship during the reigns of Constantine I and his sons; the buildings were under the imperial patronage.

- They were each located in the immediate vicinity of martyrs' graves, catacombs and cemeteries.

- None of the buildings are parish churches, but served the Christian cult of the dead; Only in the case of the basilica on Via Praenestina could no Christian connection be proven, which makes it seem conceivable that it could be erected before the other basilicas.

- The Coemeterialbasiliken can be divided into two groups: Buildings No. 1 to 4 belong to the four older ones, while the two younger ones (No. 5 and 6) differ slightly in style and have the largest dimensions.

The funeral options for the donors are different for all six coemeterial basilicas:

- On Via Labicana (No. 1) the Helenamausoleum is on an axis with the basilica.

- The grave is located on Via Praenestina (No. 2) next to the basilica in the mausoleum that was built a few years earlier.

- On the Via Appia (No. 3) there is a rectangular mausoleum on the south side of the basilica.

- On Via Ardeatina (No. 4), the donor's grave lay in the center of the basilica.

- The mausoleum of Constantina was built on Via Nomentana (No. 5) on the south side of the basilica.

- On Via Tiburtina (No. 6) there was a memorial for the martyr Laurentius from the beginning; therefore there is no donor grave there.

Again for most of the common basilicas it could be determined that each had a connection to members of the imperial family:

- On Via Labicana (No. 1) to Emperor Constantine I and his mother Helena, who was buried there.

- On Via Praenestina (No. 2) to Emperor Maximian as the father-in-law of Constantine and as the father of Maxentius and Fausta, his mother Eutropia and his wife Maximilla.

- On the Via Appia (No. 3) to Emperor Maxentius and for Constantine's wife Fausta.

- On Via Nomentana (No. 5) to the imperial daughters Constantina and Helena.

Communal basilicas in Rome

1. Basilica Santi Marcellino e Pietro on Via Labicana

The early Christian district on what was then Via Labicana (now Via Casilina) includes:

- the catacomb of Saints Peter and Marcellinus with the graves of these Roman martyrs,

- the basilica Santi Marcellino e Pietro (approx. 315–317),

- the mausoleum of the imperial mother Helena (around 326).

In the Liber Pontificalis , the chapter on Pope Silvester I reports: “At the same time, Emperor Constantine created a basilica for the blessed martyrs, the presbyter Marcellinus and the exorcist Peter, on the area between the two laurel trees and the mausoleum where his mother, Empress Helena is buried on the Via Labicana, on the third milestone ”( Lib. Pont . I, 182). From this it is deduced that Emperor Constantine the Great had the first large basilica built on the imperial estate ad duas lauros ("by the two laurel trees") in memory of the martyrs executed during the Diocletian persecution who were outside the city gates in were buried in the catacomb on Via Labicana (now Via Casilina). At that time, Marcellinus presbyter and Petrus exorcista were particularly worshiped among them . It is the oldest Christian basilica that served the cult of martyrs over the catacombs and from then on was also available for the private cult of the dead.

The side aisles of the three-aisled pillar basilica with arcades served as a walkway around the semicircular apse (in the west), which is why it is called the basilica. To the east there was a narthex in front of the slightly sloping facade .

Around 326, at the behest of Constantine, a large circular mausoleum with a rectangular vestibule was built on the east side of the basilica. It was likely to serve as his own burial place at first; in fact, however, his late Helena (mother of Constantine the Great), who died in 329, was buried there. The close connection between the Christian sacred building and the imperial mausoleum to form an axial structure is without any architectural model. Constantine donated a magnificently furnished altar for both the altar in the apse of the basilica and the mausoleum. In this way the imperial tomb was integrated into a Christian church. The entire equipment is said to have corresponded to the importance of this imperial foundation.

The building, later known as the Mausoleo di Sant'Elena, has been preserved as a mighty ruin, while only remains of the wall of the basilica can be seen.

2. Communal basilica at Tor de'Schiavi on Via Praenestina

Almost at the same time, between 315 and 320, another basilica was built on the imperial estate Subaugusta on the third milestone of the old Via Praenestina in the east of the city, in the immediate vicinity of a small catacomb and the palatial Villa Gordiani, as well as a short time before (305 –309) built mausoleum, called mausoleum at Tor (e) de'Schiavi (Schiavi tower). The mausoleum was later named by the Vincenzo Rossi dello Schiavo family, who acquired the property in the 16th century.

The three-aisled basilica resembled the building on Via Labicana in terms of size and proportions, as well as the sloping east facade and the pillar arcades inside. In the western part, a kind of presbytery was separated from the central nave in front of the arcades of the apse (as in the Basilica Apostolorum on the Via Appia).

The partially preserved mausoleum, only three meters away, was built in the tradition of the imperial circular mausoleums with a ground-level crypt and above it a hall for the memorial services. The basilica is not connected to the mausoleum either architecturally or in orientation.

The name of the small catacomb and the patronage of the burial church have not survived. The founders or property owners of the basilica and mausoleum in the 4th century are also unknown. It is believed that both buildings were donated by the imperial family; the stately villa to the west of the mausoleum is said to have belonged to the imperial Gordiani family.

3. Basilica Apostolorum on the Via Appia ( San Sebastiano fuori le mura )

The sacred district of San Sebastiano fuori le mura includes:

- the Sebastian catacomb with the tomb of the martyr and the Memoria Apostolorum (around 260),

- the basilica Basilica Apostolorum (317-320), which was consecrated in the 8th century to the martyr Sebastian and was then called San Sebastiano ad Catacumbas,

- the mausoleums attached to the basilica (4th / 5th centuries).

During archaeological excavations, a memorial site for the Apostles Peter and Paul from around 260 was discovered at the Sebastian's catacombs . It was created after Emperor Valerian had ordered (257) that Christians were no longer allowed to practice their cult in public and that they could therefore no longer meet at Peter's and Paul's tombs. Therefore, the common cult was moved to the underground cemetery ( cymeterium catacumbas ) on the Via Appia and a memoria apostolorum was established there . The trapezoidal memorial complex (23 m × 18 m) consisted of an inner courtyard with two covered loggias , between which a staircase led down to a spring. The eastern loggia used by the Christians, called triclia , was slightly elevated and had wall paintings depicting flowers and animals. Numerous graffiti with invocations of the apostles Peter and Paul in Greek and Latin were also found in the plastering .

Around 317 this memorial complex was the reason for the imperial family who had become Christian to build a burial basilica over the memorial for Peter and Paul and the grave of the martyr Sebastian, despite the architecturally unsuitable terrain; because on the area used in early Christian times as a cemetery with the field name ad catacumbas (from Greek κατά κύμβασ = "near the caves") there were pits from the earlier mining of pozzolan soil , which led to the construction of approximately 8 m high pillars under the West building made necessary. This hallway name was added to the name of the basilica in the 8th century as San Sebastiano ad Catacumbas and was then used as the technical term " catacomb " for underground burial sites and, in modern times, for rooms deep inside or underground in modern buildings or sports facilities.

A three-aisled pillar basilica was built in the form of a basilica, with a semicircular walkway in the west and a vestibule in the east separated by transverse arcades, again with a sloping facade. There were arcade pillars between the nave and the choir to delimit the presbytery. It is believed that the altar was not in the presbytery, but in the middle of the nave and thus almost exactly above the 3rd century Triclia . The basilica was illuminated through large arched windows in the upper storey and narrow slits of light in the side aisles.

On the west and south sides of the basilica, mausoleums with graves of important families were built in the 4th and 5th centuries. The oldest of these mausoleums, which may have been intended as the burial place of the Constantinian family, has evidently been built at the same time as the basilica. To the east, there were two more tombs in the form of a spacious apsidal hall and a round mausoleum with a vestibule from around 349. Under Pope Damasus I (366–384), a semicircular mausoleum adorned with colored stucco decorations was added to the apse of the basilica.

The Basilica Apostolorum , later called San Sebastiano ad Catacumbas, is the only one of the Roman basilicas that has been largely preserved despite all the renovations, thanks to its uninterrupted sacral use.

4. Communal basilica on Via Ardeatina

In 1991, near the Catacomb of Calixtus and approx. 600 m from the location Domine, quo vadis? Between the Via Ardeatina and the Via Appia, about 1 km before the Porta Appia , another funeral basilica was discovered, the construction of which, according to the latest excavation results, can be expected around 336. If this dating is correct, it could be the burial basilica mentioned in the Liber Pontificalis , which is said to have been built on imperial property by Pope Mark (336) with financial support from Emperor Constantine. According to the wording of the Liber Pontificalis, the building was planned from the beginning as a funeral basilica ( quam coemeterium constituit ).

The basilica had circumferential side aisles and otherwise corresponded to the type of a coemeterial basilica. Arcaded pillars separated the nave from the aisles. There was a spatial separation between the presbytery and the nave by three arcades. The floor of the basilica was covered with tombs; Here, too, it was a question of 'shaft graves', which were bordered by walls and covered in the length of a gable-shaped with brick plates placed against each other, sometimes also in several levels one above the other. The floor covering above often consisted of marble slabs. A tomb in the middle of the presbytery, privileged by its location and size, must have been planned when it was built. Therefore the burial place intended for Pope Marcus as donor is assumed here; This is also supported by the later name of the basilica as San Marco sull'Ardeatina. According to the inscriptions found, the burials took place in the period from 368 to 445. A small square mausoleum with a portico was built to the northeast of the apse .

The names of the martyrs to whom the basilica was consecrated could not yet be determined; The connection with the catacomb just a few meters to the east is also unknown. After the remains of the founder pope were transferred to the inner-city basilica San Marco (Rome) in the 12th century, the burial church began to fall apart through stone robbery.

5.The Basilica of Sant'Agnese on Via Nomentana ( Sant'Agnese fuori le mura )

The area around the basilica includes:

- the catacombs on Via Nomentana with the tomb of the martyr Agnes of Rome (3rd century),

- the communal basilica Sant'Agnese ( Coemeterium Agnetis ) from around 337,

- the mausoleum of Constantina (daughter of Constantine the Great) from the same period (today Chiesa di Santa Costanza),

- the gallery basilica Sant'Agnese fuori le mura from approx. 630 (“Honorius-Bau”).

According to tradition, Constantina (daughter of Constantine the Great) founded the basilica on the imperial estate ( Suburbanum ) on Via Nomentana between 337 and 343 in honor of St. Agnes of Rome who was buried there (died around 251). It was the largest of the previous burial churches in Rome (98 m × 40 m), of which the outer walls of the huge apse and the south aisle wall have been preserved. From the former forecourt, a wide staircase led down to the tomb of the saint, who was highly venerated in Rome.

Just a few years after the start of construction, Constantina had her own mausoleum built next to the south aisle, in which she and later her sister Helena (daughter of Constantine the Great) were buried (354 and 360). As a further development of the traditional Roman round mausoleums, this representative building was erected for the first time on a floor plan with three concentric circles. In addition to the well-preserved round mausoleum with its extraordinary architecture, the magnificent Constantina sarcophagus made of red porphyry (around 320) with scenes of harvesting and pressing the grapes is also reminiscent of the donor Constantina, which is now set up in the apse opposite the entrance . The oldest mosaics of Christian monumental architecture (around 350) have been preserved in this rotunda .

In the barrel vault of the gallery, eleven trapezoidal vault areas are decorated according to pagan models with geometrical and floral patterns, with vases and birds, laurel branches and grain yolks; the interspersed images of the transport and pressing of the grapes can be iconographically traced back to the Dionysus cult; at this point they should indicate death and rebirth. In contrast to this, the mosaics in the two lateral apsidioles show early Christian motifs (around 370), namely the traditio legis (south-eastern apse) and traditio clavis (north-western apse). In contrast to these motifs, the type of representation still follows the models in the imperial court ceremony of the Constantinian period, namely the ruler standing at the representation and seated at the distribution of gifts ( adlocutio and largitio ).

6. Basilica Maior on Via Tiburtina ( Saint Laurentius Outside the Walls )

The sacred area around the basilica includes:

- the catacomb on Via Tiburtina (3rd century) with the tomb of the martyr Lawrence of Rome ,

- the Constantinian basilica, called Basilica maior (337–351),

- the basilica of San Lorenzo fuori le mura from around 580 ("Pelagius building") above the Laurentius tomb with apse in the west and narthex in the east,

- the extension of a new nave in the west and the conversion of the "Pelagius building" as a confessio and choir room in the east and a new portico in the west ("Honorius building") after 1200.

The youngest of all colonial basilicas in the city, built according to plans by Constantine I and the Roman bishop Silvester I from 337, was also an imperial foundation. It was built on the Fundus Veranus estate (named after Emperor Lucius Verus ), which also includes today's Campo Verano cemetery, around 25 m south of the tomb of the martyr Laurentius ( supra arenario cryptae = above the sand hill of the crypt ). It was a three-aisled basilica with surrounding side aisles and (for the first time) with columns as inner supports that carried an architrave . The entire floor was covered with graves. The facade in the east was opened by a column position with five arcades. In comparison with the older colloquial basilicas, greater emphasis was placed on rich decor and sumptuous interior fittings; contemporaries described the building as a church with royal furnishings. There were several mausoleums and ancillary structures around the basilica. On the north side a double flight of stairs (since about 360) led down to the catacomb with the martyrs grave.

Approx. In 580 Pope Pelagius II had a smaller Laurentiuskirche ("Pelagius-Bau") built on the north side of the basilica exactly above the Laurentius tomb; for this purpose, the hill above the catacomb had to be partially removed and half of the new building, also a gallery basilica, had to be built underground. In the crypt under the presbytery, the bones of St. Lawrence are kept in an ancient sarcophagus; later the relics of the arch-martyr Stephen were transferred here so that both city patrons of Rome could be venerated here together. Of the mosaics donated by Pelagius II, only the one on the apse arch has survived. Pope Honorius III. in the period after 1200 had the apse of the Pelagius building in the west torn down and a new nave with a vestibule added ("Honorius building"); the previous nave of the Pelagius building was raised and transformed into the new choir with confessio and main altar in the east. The ciborium , bishop's throne , ambo , Easter candlestick and floor are mosaic works by the cosmats .

See also

literature

- Hugo Brandenburg : The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century . Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2013, pp. 54ff., 93–96, 289–301.

- Walther Buchowiecki : Handbook of the Churches of Rome. The Roman sacred building in history and art from early Christian times to the present . Hollinek, Vienna 1967–1997, Vol. 1–4.

- Steffen Diefenbach : Roman memory rooms. Memory of saints and collective identities in Rome from the 3rd to 5th centuries AD , Berlin 2007, pp. 97–122, 153–181 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai: Early Christianity in "Domine Quo Vadis". The newly found early Christian basilica on the Via Ardeatina in Rome . In: Antike Welt 29 (1998), p. 305ff.

- Richard Krautheimer u. a .: Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae. Le Basiliche cristiane antiche di Roma (sec. IV – IX) , Vol. IV, Città del Vaticano 1980.

- Ursula Leipziger: The Roman basilicas with handling. Research history inventory, historical classification and primary function . Diss. Erlangen 2006. https://d-nb.info/980638372/34

- Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - A Vademecum . Herder, Freiburg, 2nd edition 2017, pp. 34, 67–101.

Individual evidence

- ↑ World and Environment of the Bible. Archeology - Art - History. On the way to the cathedral, special issue: Development of church building, 2000, p. 13

- ↑ Ursula Leipziger: The Roman basilicas with handling. Research history inventory, historical classification and primary function, Erlangen 2006, pp. 92-101

- ^ Hugo Brandenburg: The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century, Regensburg 2013, pp. 54–95 and 301

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian Sacred Buildings from the 4th to the 9th Century - Ein Vademecum, Freiburg, 2nd edition 2017, pp. 67-104

- ^ Peter Grossmann: Christian architecture in Egypt. Brill, 2002, ISBN 978-90-04-12128-7 , pp. 28ff.

- ↑ Hugo Brandenburg: The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century, Regensburg 2013, p. 94

- ↑ Ursula Leipziger: The Roman basilicas with handling. Research history inventory, historical classification and primary function, Erlangen 2006, p. 177ff.

- ↑ Walther Buchowiecki: Handbook of the Churches of Rome. The Roman sacred building in history and art from early Christian times to the present. Vienna 1970, Vol. 2, pp. 331-335

- ↑ Steffen Diefenbach: Roman memory rooms. Memory of saints and collective identities in Rome from the 3rd to 5th centuries AD, Berlin 2007, pp. 97, 100f., 111, 118, 155ff., 165f., 169ff., 173ff.

- ↑ Ursula Leipziger: The Roman basilicas with handling. Research historical inventory, historical classification and primary function, Erlangen 2006, p. 33ff.

- ^ Hugo Brandenburg: The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century, Regensburg 2013, pp. 60ff.

- ↑ Steffen Diefenbach: Roman memory rooms. Memory of saints and collective identities in Rome from the 3rd to 5th centuries AD, Berlin 2007, pp. 97, 101, 105f., 158ff., 165f., 177f.

- ↑ Ursula Leipziger: The Roman basilicas with handling. Research historical inventory, historical classification and primary function, Erlangen 2006, p. 28ff. and 151ff.

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian Sacred Buildings from the 4th to the 9th Century - Ein Vademecum, Freiburg, 2nd edition 2017, p. 79ff. with a plan of the memoria, basilica and mausoleums

- ↑ Steffen Diefenbach: Roman memory rooms. Memory of saints and collective identities in Rome from the 3rd to 5th centuries AD, Berlin 2007, pp. 97, 100f., 105ff., 117f., 155ff., 177f.

- ↑ Ursula Leipziger: The Roman basilicas with handling. Research historical inventory, historical classification and primary function, Erlangen 2006, p. 40ff.

- ↑ Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai et al. a .: Rome's Christian Catacombs, Regensburg 2000, p. 9

- ↑ Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai: Early Christianity in "Domine Quo Vadis". The newly found early Christian basilica on the Via Ardeatina in Rome. In: Antike Welt 29 (1998), p. 305ff.

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - Ein Vademecum, Freiburg, 2nd edition 2017, p. 86ff. with floor plan

- ↑ Ursula Leipziger: The Roman basilicas with handling. Research historical inventory, historical classification and primary function, Erlangen 2006, p. 47ff.

- ^ Hugo Brandenburg: The early Christian churches in Rome from the 4th to the 7th century, Regensburg 2013, p. 71ff.

- ↑ Steffen Diefenbach: Roman memory rooms. Memory of saints and collective identities in Rome from the 3rd to 5th centuries AD, Berlin 2007, pp. 97, 100, 106f., 118, 156ff., 173f.

- ↑ Ursula Leipziger: The Roman basilicas with handling. Research historical inventory, historical classification and primary function, Erlangen 2006, p. 14ff.

- ↑ Wilpert / Schumacher: The Roman mosaics of the church buildings from IV. - XIII. Century, Freiburg 1976, p. 300

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: Rome - The Christian sacred buildings from the 4th to the 9th century - Ein Vademecum, Freiburg, 2nd edition 2017, p. 99ff. with floor plan and elevation drawing

- ↑ Steffen Diefenbach: Roman memory rooms. Memory of saints and collective identities in Rome from the 3rd to 5th centuries AD, Berlin 2007, pp. 97, 100, 106ff., 117f., 158ff.

- ↑ Ursula Leipziger: The Roman basilicas with handling. Research historical inventory, historical classification and primary function, Erlangen 2006, p. 20ff.

- ↑ Anton Henze u. a .: Art Guide Rome, Stuttgart 1994, p. 197