Heidelberg Catechism

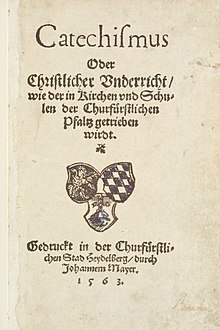

The Heidelberg Catechism ( Latin Catechesis Palatina ) is the most widespread catechism of the Reformed Church . He was on the initiative of Elector Friedrich III. mainly drawn up by Zacharias Ursinus and published in Heidelberg in 1563 under the title Catechism or Christian Vnderricht, as is carried out in the churches and schools of the Electoral Palatinate . The catechism is at the same time a textbook for church and school, a confessional document , a book of consolation and prayer, and a template for a wealth of edifying literature .

history

The Heidelberg catechism was originally the catechism for the Reformed regional church of the Electoral Palatinate . There it served as a textbook and lesson book in church and school.

Frederick II introduced the Lutheran Reformation in the Electoral Palatinate in 1545/1546 , but this was soon suppressed by Emperor Charles V. The new Elector Ottheinrich had the opportunity to reintroduce the Reformation in 1556 through the Peace of Augsburg . But he died as early as 1559 and was thus unable to complete his work of Reformation, which resulted in church disorder, disputes and disagreement. Thereupon tried his successor Friedrich III. - but in vain - to at least establish a middle path in the doctrine of the Lord's Supper, which came from Philipp Melanchthon . In June 1560 a disputation in Heidelberg convinced him of the Reformed conception of the Last Supper. A precise and uniform teaching basis in church and school as well as the introduction of a revised church order became necessary.

In order to achieve this, Friedrich III called. 1560/1561 several professors went to Heidelberg. Among them also Zacharias Ursinus, a pupil of Melanchthon and Calvin , as well as Caspar Olevian , a pupil of Calvin and friends with the son of Frederick.

On behalf of the elector, Ursinus began work on the catechism in 1562. Presumably other professors were also involved in the work. Two Latin drafts of the catechism were found in the estate of Ursinus. The shorter draft was probably the original version, which was heavily revised and expanded, including parts of the longer draft, which was intended for academic teaching. Several catechisms were consulted for the preparation, including Martin Luther's Small Catechism as well as Calvin's Geneva Catechism and a Geneva Church Prayer, most of which provided the interpretation of the Our Father. A commission made up of theologians from Heidelberg University, the pastors of the city of Heidelberg and the elector himself was responsible for the final version. Caspar Olevian, although long accepted, was not a co-author of the catechism, but was a member of the commission and was significantly involved in its introduction, since he had been pastor and leading theologian in the church council in Heidelberg since 1562.

At the beginning of 1563, Friedrich III. all superintendents of the Electoral Palatinate to Heidelberg to discuss and adopt the final version. On January 19, 1563, the elector signed his preface to the catechism. The first edition with 128 questions and answers appeared in March of the same year. Subsequently, Olevian Friedrich III. to the addition of another - the current 80th - question. At the beginning of April the second edition, now with the additional question, was published. In the meantime, Josua Lagus and Lambert Pithopoeus created a Latin translation of the catechism. In the third edition it was divided into ten lessons and at the same time, in order to be able to complete it in one year, into 52 Sundays.

In August 1563, another conference of the superintendents passed the new church order, the preface of which the elector signed on November 15th. The catechism was also fully incorporated into it.

In 1566 Friedrich III. accused by several Lutheran dukes of Emperor Maximilian II of having deviated from the Augsburg Confession . At the Reichstag in Augsburg, the emperor threatened him with the imperial ban if he did not withdraw his church changes. Friedrich was steadfast and confessed his faith. Since the majority of the princes at the Reichstag were against his exclusion, the emperor was incapable of acting in this regard. One reason that spoke against punishment was the wealth and political importance of the Electoral Palatinate in the Holy Roman Empire . By not being expelled, Friedrich was able to continue his work of the Reformation.

The Heidelberg Catechism was rapidly and widely spread. The Dutch refugee community in Frankenthal also accepted the catechism and proposed its use in the Netherlands in 1568 at the Wesel convent . In 1571 this was confirmed by the Synod of Emden . Since the Reformed of the Lower Rhine were also present at this synod , from 1571 it became not only the catechism of the Dutch, but also the Lower Rhine. In 1567 the Reformed Church in Hungary accepted it at the Synod of Debrecen .

Around 1580 several countries in the Holy Roman Empire switched to the Reformed faith and mainly adopted the Heidelberg Catechism. These included Nassau-Dillenburg , Sayn-Wittgenstein , Solms-Braunfels , Wied , Isenburg-Büdingen , Hanau-Münzenberg , Moers , Pfalz-Zweibrücken , Pfalz-Simmern , Anhalt , Tecklenburg , Bremen , Bentheim , Lingen and Lippe .

At the first reformed general synod from 7th to 11th September 1610 of the united duchies of Jülich-Kleve-Berg , the catechism was accepted as a textbook and instruction book. Even if the Reformed churches in Switzerland have understood themselves to be free of denial since the mid-19th century, it was accepted by St. Gallen in 1615 , by Schaffhausen in 1643 and by Bern in the 18th century . The Dordrecht Synod from 1618 to 1619 confirmed the catechism as a confessional document. In 1655 it was introduced in Hessen-Kassel . In 1713 it found its way into the German reformed communities in Prussia together with church ordinances. In East Frisia the Emden catechism was used until the beginning of the 18th century. He also came to North America and South Africa through emigrants.

The Heidelberg Catechism has been translated into 40 languages and is still popular around the world, especially in countries with a reformed character such as the Netherlands, Switzerland and Hungary. Only in the French and English-speaking countries did it initially not spread widely, as either the Confessio Gallicana (1559) or the Confessio Scotica (1560) - and later the Puritan Confession of Westminster - were already in possession there.

The Heidelberg Catechism was also highly valued by Karl Barth (cf. his work The Christian Doctrine according to the Heidelberg Catechism ).

In 1977 the Reformed Federation issued an ecumenical declaration on the 80th question.

For the anniversary “450 years Heidelberg Catechism” in 2013, several celebrations, lectures and exhibitions were planned, among others in Heidelberg and Apeldoorn . The reformed pastor i. R. Günter Twardella created the volume Heidelberger Buchmalerei for the occasion , in which he compiles selected texts from the Heidelberg Catechism "in old script with new explanations". In this way Twardella designed essential questions of the catechism for him calligraphically in writing and jewelry and reinterpreted them from his theological point of view. On the occasion of the anniversary, the composer Dietrich Lohff wrote the oratorio Das Spiel von der Schnur Christi , which was premiered on January 19, 2013 in Mannheim by the choir of the Protestant student community in Heidelberg.

content

The Heidelberg Catechism, which comprises 129 questions and answers, is essentially divided into three large parts:

- Of man's misery (the knowledge of sin )

-

Of man's redemption (the knowledge of redemption )

- From God the Father

- From God the Son

- From God the Holy Spirit

- From the holy sacraments

- From holy baptism

- From the holy supper of Jesus Christ

-

From gratitude (an ethic of gratitude )

- From prayer

The first two questions serve as an introduction, so to speak, the first being a summary of the Catechism. The first part reveals to man the knowledge of sin from the law of God. The second part is about the knowledge of salvation. It deals with the apostolic creed , baptism and the Lord's Supper at the same time . In the last, third part “people should be asked and reminded to live in gratitude in thoughts, words and works for their salvation from misery” ( Paul Kluge :). Furthermore, the Decalogue and the Lord's Prayer are interpreted in this part .

What is remarkable about the theological concept is the fact that all cultic achievements (such as prayer) as well as ethical ones (the “good works”) are classified in the third part. This clearly states that in the Reformed view the “good works” are never there to be credited before God. Rather, they are a grateful and natural answer to the unconditional grace of God, which is bestowed upon people through Christ.

Step by step, the three parts of the Heidelberg Catechism show people the way from the knowledge of sin to the knowledge of redemption to a life in accordance with faith in gratitude for redemption from misery.

literature

- expenditure

- The Heidelberg Catechism along with the relevant evidence from Holy Scripture. Schmachtenberg, Duisburg 1841 ( digitized version )

- The Heidelberg Catechism. For teaching young people in Protestant communities. ed. from the moderamen of the Reformed Covenant. Simplified edition, 12th edition. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1993, ISBN 3-7887-0273-7 .

- The Heidelberg Catechism. Edited by Otto Weber . Gütersloher Taschenbücher Siebenstern 1293. 5th edition. Gütersloher Verl.-Haus, Gütersloh 1996, ISBN 3-579-01293-2 .

- The Heidelberg Catechism. Edited by the Evangelical Reformed Church (Synod ev.-Ref. Churches in Bavaria and Northwest Germany), rev. Edition Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, ISBN 3-7887-1570-7 .

- Wilhelm H. Neuser : Heidelberg Catechism of 1563. In: Andreas Mühling , Peter Opitz (Ed.): Reformed confessional documents. Vol. 2/2: 1562-1569. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2009, pp. 167-212.

- Secondary literature

- Walter Henss: The Heidelberg Catechism in the denominational play of forces of its early days. Historical-bibliographical introduction of the first complete German version, the so-called third edition. from 1563 and the corresponding Latin version. Theological Publishing House, Zurich 1983, ISBN 3-290-11537-2 .

- Wulf Metz, Jürgen Fangmeier : Heidelberg Catechism I. Church History II. Practical Theological. In: Theological Real Encyclopedia . Volume 14. 1985, pp. 582-590.

- Eberhard Busch : Devoted to freedom. Christian Faith Today - In Conversation with the Heidelberg Catechism . Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1998, ISBN 3-7887-1623-1 .

- Alfred Rauhaus : Understanding Faith. An introduction to the thoughts of Christianity based on the Heidelberg Catechism. Foedus-Verlag, Wuppertal 2003, ISBN 3-932735-77-3 .

- Thorsten Latzel: Theological basics of the Heidelberg Catechism. A fundamental theological investigation of his approach to the communication of faith (= Marburg theological studies 83). Elwert, Marburg 2004, ISBN 3-7708-1259-X .

- Ulrich Löffler, Heidrun Dierk: Small book, great effect. Heidelberg 2012.

- Karla Apperloo-Boersma, Herman Johan Selderhuis (ed.): Power of Faith - 450 Years of the Heidelberg Catechism. Göttingen 2013.

- Matthias Freudenberg , J. Marius J. Lange van Ravenswaay (ed.): History and effect of the Heidelberg catechism. Lectures of the 9th International Emden Conference on the History of Reformed Protestantism (= Emden Contributions to Reformed Protestantism 15). Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2013, ISBN 978-3-7887-2738-3 .

- Christoph Strohm , Jan Stievermann (Hrsg.): Profile and effect of the Heidelberg Catechism. New research articles on the occasion of the 450th anniversary (= writings of the Association for Reformation History ; Vol. 215). Gütersloher Verlagshaus 2015, ISBN 978-3-579-05996-9 .

- Boris Wagner-Peterson: Doctrina schola vitae. Zacharias Ursinus (1534–1583) as an interpreter (= Refo500 Academic Studies 13). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-525-55055-7 (= dissertation University of Heidelberg 2011).

Web links

- Website about the Heidelberg Catechism

- Digitized version of the first edition - Heidelberg University

- Digitized version of the Latin edition - Johannes-a-Lasco Library

- Links to the Heidelberg Catechism on Reformiert-info.de

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Paul Kluge: The Heidelberg Catechism II. An introduction. Retrieved January 9, 2011 .

- ↑ a b H. Graffmann: Heidelberg Catechism. From: Religion in Past and Present, 3rd edition. Vol. 3, pp. 128ff. Retrieved January 9, 2011 .

- ↑ Thomas Juelch: Calvinism in the Electoral Palatinate. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 4, 2005 ; Retrieved January 9, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Georg Plasger , Matthias Freudenberg : Reformed confessional documents. A selection from the beginning to the present , 1st edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, p. 173 online edition

- ↑ 2013 exhibition: “450 Years of Heidelberg Catechism”. Retrieved January 9, 2011 .

- ↑ Günter Twardella: Heidelberger illumination. A festive reading book. Selected texts from the Heidelberg Catechism in old script with new explanations. Calligraphically designed and explained, ISBN 978-3-00-038115-7 .

- ↑ The Game of the Cord of Christ. Retrieved January 6, 2013 .

- ↑ The Heidelberg Catechism I . In the Misery - Salvation - Gratitude section . Retrieved January 9, 2011

- (G) JF Gerhard Goeters: On the history of the catechism. In: Heidelberg Catechism. Revised edition 1997, 3rd edition. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2006, ISBN 3-7887-1570-7 , pp. 83-96 PDF file