County of Moers

|

Territory in the Holy Roman Empire |

|

|---|---|

| County of Moers | |

| coat of arms | |

|

|

| map | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Alternative names | Mörß, Mors, Murs, Meurs |

| Arose from | Duisburggau |

| Form of rule |

County , from 1706 principality |

| Ruler / government | Count , Prince |

| Today's region / s | DE-NW |

| Parliament | Reichsfürstenrat , Secular Bank: part of a 1 curiate vote of the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Count College; from 1702: 1 virile vote |

| Reich register | 3 horsemen, 12 foot soldiers, 45 guilders (1522) |

| Reichskreis | Lower Rhine-Westphalian |

| Capitals / residences | Moers |

| Dynasties | House Moers, from 1493 Wied , from 1519 Neuenahr , from 1600 Nassau-Orange , from 1702 Brandenburg-Prussia |

| Denomination / Religions | Roman Catholic , Protestant from 1560 |

| Language / n | Dutch , Kleverland |

| surface | 180 km² (around 1800) |

| Residents | 38,000 (around 1800) |

| Incorporated into |

France, Département de la Roer (1798–1813)

|

The county of Moers was a historical territory on the left Lower Rhine , which included parts of the cities of Moers and Krefeld as well as some surrounding towns and areas. Although the county was legally dissolved as early as 1797/1801, it is still often referred to as “Grafschafter” as an additional term in names for municipal institutions and companies.

history

Time before the Counts of Moers

After the Romans withdrew from the Lower Rhine , no documents were known for the area of the later county for the next few centuries. For the 4th to 6th centuries only very few Franconian finds were unearthed in the Asberg area. In 1932 a Franconian grave was found in Eick-West. But it was not until 1957 that this area was examined more intensively. By 1959, 163 graves, some of which were rich in grave supplements, had been excavated. The main period of use of this grave field was between 570 and around 650 AD. The oldest settlement find in the city center of Moers, a blue-gray spherical pot, dates from the 9th century and indicates settlement before the first buildings were erected in the castle area.

The next confirmed documentary reports for the area do not exist until the 9th century. The fact that Charlemagne is said to have held a Reichstag in Friemersheim in 799 refers to a presumably forged document.

In a document from 855, a nobleman "Hattho" gave the Echternach monastery a large manor with forest, meadows, water, mill and 42 servants in the area of "Reple". Some historians suggested that today's Repelen would have been this Reple. The village church there is one of the oldest churches on the left Lower Rhine, as it was originally supposed to have been consecrated as a small chapel in the 7th century by the abbot of the Echternach monastery , Willibrord , in the name of Saint Martin.

The Werden monastery , which was founded towards the end of the 8th century, was demonstrably donated as a benefice in the 9th century and later some farms and areas in the area of the later county . In the registers of this monastery, a noble person from the Moers area was mentioned for 1160. In the Codex Ulphilas from the abbey archive it is stated: "Wilhelmus .. Comes de Moers .. annis 8. obiit 1160 20 Junii" . This Count Wilhelm was abbot of the abbey from 1152 to 1160 and thus the first reference to the Lords of "von Moers".

The next noble lords that can be documented were Elgerus and Theoderich de Murse . As witnesses, they had also notarised a settlement by the Archbishop of Cologne for a dispute between Ossum and Kerpen in 1186. This “testimony” by the noblemen de Murse shows that the later “Counts of Moers” originally belonged to the vassal area of the archbishops of Cologne. Another reference to this is the oldest known Moerser jury seal. This is used in a document from 1306. In this document, the knight Dietrich von Moers decided a legal dispute by Moers aldermen. Since the Neuss jury court was the next higher instance (Oberhof) for the jury courts of Moers and Krefeld until the middle of the 15th century, the initial affiliation of the noble lords de Murse to the sphere of influence of the Cologne archbishops is also recognizable.

County location and areas

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the county of Moers was surrounded by areas of the Archdiocese of Cologne in the north and south, the county of Kleve in the east, the county of Berg in the south-east and the county of Geldern in the west. While the county of Kleve, which lies north of the Archdiocese of Cologne, succeeded in finally ending this dependency in 1417 by the Roman-German King Sigismund and, like Geldern and Berg, also became a duchy , Moers was not able to do this. Since the relatively small county of larger counties and Electoral Cologne area was surrounded, this resulted in the supremacy of Moers to changing dependencies and the respective recognition Electorate of Cologne and / or these counties or later duchies. This only ended in 1600 with the suzerainty of the Orange, which was replaced by that of Brandenburg-Prussia from 1702 to 1946, only interrupted by France from 1796 to 1813.

- In addition to the city of Moers the territory including in particular today to Duisburg belonging neighborhoods and areas Baerl , Friemersheim , Hochemmerich , Rumeln with parts of Kaldenhausen , Östrum and Homberg , the area of the present town Neukirchen , chapels and Repelen .

- As an exclave within the Electorate of Cologne, Krefeld , located southwest of Moers, with the now submerged Crakau Castle (seat of Moerser Drosten ) belonged to the county . In addition, the so-called Papenburg with an associated street section ( Moersische Strasse ) was part of the county - based on an old inheritance contract - in today's Krefeld district of Hüls .

- Some smaller areas on today's right bank of the Rhine, such as Kasslerfeld in Duisburg on the left bank of the Rhine from the 12th century onwards , belonged to the County of Moers until 1795/1801.

- In addition to these areas, Brüggen , Dülken , Dahlen , Süchteln and Wassenberg were part of the county for a few years , but only briefly in the Middle Ages .

- In 1399 the empire-direct county Saar Werden was added; but as early as 1417 it was split off again as the county of Moers-Saar Werden.

Time of the Counts of Moers

It is not yet known where the original first allodial area of the first noblemen of Moers was. The first officially verifiable purchase of a piece of land in the area of the castle complex in Moers dates back to 1288. At this time, the noblemen Dietrich and Friedrich von Moers bought property here from the Werden Abbey .

Dietrich I. von Moers (1226–1262) (Dietrich also written Theodorich) is the first documented ruling count. In a document from 1226 he certified that the "Abbey Camp" had acquired a piece of land. It was followed by his son and heir Dietrich II. (1262–1294) and the other members of this noble family, who are specified in the chapter "Acting Counts of Moers". Dietrich II and Count von Geldern took part in the Battle of Worringen on the side of Kurköln , which decided the Limburg succession dispute in 1288 and changed the balance of power, especially in the Maas and Lower Rhine area (see Treaty of Vinnbrück ). In order to secure himself in case the party to which he belonged should lose, he had previously recognized the feudal sovereignty of the Counts of Kleve for the Moers area. Kleve was neutral in this conflict and therefore could after the war the fallen into captivity Count of Moers, the fief and thus obtain the ownership of the county.

This fiefdom dependency of Kleve was later often controversial. Friedrich I , incumbent Count von Moers from 1346 to 1356, did not recognize this. His successor Dietrich VI. She confirmed in writing when he took office in 1356, but then achieved that Kleve confirmed in a document in 1361 that Moers Castle and Land was not a man's fief of Klever.

However, the later legal successors for the Duchy of Kleve repeatedly asserted feudal jurisdiction . For example, in the opinion of Count Adolf II of Kleve, the County of Moers was a Klevian fief. The dispute over this with Friedrich III. von Moers was decided by the Bishop of Cologne in an arbitration award that this fiefdom be for the term of office of Friedrich III. is valid.

The county of Moers gradually developed from what was originally only a small area that had belonged to the nobles of Moers . As was common at the time, new territories were acquired either by force or by purchase. In addition, the rulership rights could be extended and secured through legally formal recognitions towards the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century. For example, King Ludwig the Bavarian confirmed to Count Dietrich III. von Moers wrote in 1317 that he was responsible for both wild bans in the area he was given by Kleve as a fief and that he was allowed to collect road money.

In the endeavor to enlarge their territory, however, resistance from the old owners often had to be overcome. An example of this is the acquisition of the Friemersheim area by the counts. In this area the Werden Abbey owned many farms and estates. In order to secure this, the abbot committed in writing in 1297 to the bailiff of the abbey not to transfer the bailiwick of Friemersheim with Borch and Vluyn to the counts of Moers and to grant a fiefdom of the abbey in this area, the knight Wilhelm von Friemersheim , against the lords of Moers support. In 1366, however, Bodo von Friemersheim ran into financial difficulties and pledged his rights to the knight Johann von Moers for 11800 golden shillings . Since the pledge was not redeemed, the Werden Abbot Johann von Spielberg had to transfer the rule of Friemersheim to the Counts of Moers as a fief in 1385. In 1392 the lordship of Friemersheim with the possessions in Vluyn legally became part of the county through additional purchases.

With Count Dietrich IV. , Who ruled from 1356 to 1372, the local importance of the county began to strengthen significantly. With the support of the Moerser for Eduard von Geldern , a rapprochement with this duchy began. This led to the loosening of the old dependencies that had existed on both Kurköln and Grafschaft Kleve. Another advantage was that knight Johann von Moers had supported Eduard von Geldern in 1364 with 30,000 gold shields. For this he received the pledge of the areas Millen and Waldfeucht with the city of Gangelt in Geldern. Since Gangelt had the right to mint, Moers could now strike coins.

Thanks to the good relationships that both Dietrich IV and his brother, knight Johann, had with Emperor Karl IV , the Moersers earned additional income. In 1371 knight Johann von Moers received permission from the emperor to levy a duty on goods “on land and at sea” in the area of the Friemersheimer or Homberger Werth in the amount of four turnoses per inch. This customs permit was changed as early as 1372, and now, in addition to Knight Johann, Count Friedrich von Moers and Engelbert III. von der Mark jointly authorized to raise this Rhine toll. With the approval of Count von Moers, knight Johann leased his rights to Count Engelbert von der Mark in 1372 against payment of a hereditary interest of 50 shields per year.

In 1379 the German King Wenzel revoked all Rhine tolls between Andernach and Rees. A short time afterwards, however, the approval of the customs for those entitled from 1372 was again granted in the Homberger Werth area. In 1392 the Counts of Kleve and von der Mark agreed that the portion of the customs authorization of Count Engelbert would go to the Count of Kleve after his death and that he would pay the rent of 50 shields to the Moerser.

From 1393 onwards, the entire customs revenue came into the hands of the Moerser through pledging. The approval for the collection of customs by the Counts of Moers was confirmed by King Wenzel in 1398 . In addition, the king, Count Adolf I of Kleve and Count Dietrich I of the Mark , asked not to hinder the Moerser from collecting tariffs. 1411 was by an arbitration decision of the Archbishop of Cologne Friedrich III. once again confirmed the responsibility of Moers for the Rhine toll, which from 1541 came into the possession of the dukes of Kleve without restriction.

With a further approval by the emperor in 1373, the counts were allowed to operate a mint in Friemersheim or Diedem. The permit concerned the minting of gold florin and silver coins. As already mentioned in the example for Friemersheim, thanks to the increased financial possibilities of the count family, many territories could be acquired and influence on power-political decisions in the area of the Lower Rhine could be achieved through the granting of pledges and the use of money.

The county gained the greatest local power under Friedrich III. who acquired inheritance claims to the county of Saar Werden through marriage , which could be realized in 1399. He thus ruled over two counties that were spatially separate but united under a Count of Moers. Since Friedrich's brother-in-law Friedrich III. von Saar from 1370 to 1414 and after him Friedrich's son Dietrich II. von Moers from 1414 to 1463 were archbishops of Cologne, this also increased the local importance on the Lower Rhine. Already after the death of Friedrich III. was dissolved again through a division of the association of the two counties. In all later alliances with Moers, noble houses from other territories were in charge.

After Friedrich III. followed by his son Friedrich IV of Moers as acting count. In 1421 he acquired the Jülich areas of Born , Sittard and Susteren by pledging , which were later released by Jülich-Berg . After Friedrich IV von Moers, Vincenz von Moers was the last count from this family, who ruled the county from 1448 to 1493. His rule fell in a period in which a number of local wars were waged on the Lower Rhine and the area of what is now the Netherlands and Belgium over the affiliation and the extent of some counties and duchies. As an ally of Dukes Adolf and his son and successor Karl von Geldern, he was involved in the wars of Duke Charles of Burgundy for the Duchy of Geldern and with Kurköln as his opponent.

Although Vincenz had been appointed patron of the duchy by the estates in Geldern in 1471, he had to shrink from the superior financial and military possibilities of the Burgundian. In 1473, Charles of Burgundy largely conquered the Duchy of Geldern. The county of Moers was conquered and occupied by the Burgundian troops in July 1473, and Vincenz had to flee. Then the troops moved south towards Neuss. The siege of Neuss from July 1474 was ended in May 1475 by the intervention of an imperial army with an armistice. Charles the Bold withdrew with his troops towards Switzerland and northern France and the county of Moers was also freed again.

Count Vincenz returned to Moers and normal conditions returned to the county. However, the count was heavily in debt due to his military support of Geldern and later Kurköln. The promised repayments for his expenses were still recognized, but only to a small extent actually paid. Because of his high debts and his advanced age, Count Vincenz contractually handed over his castles and towns to Duke Wilhelm von Jülich-Berg for 14 years in 1480 . After the agreed time, castles and towns were to be handed over to his grandson, Young Count Bernhard, who lived at the Duke's court.

Despite his severely limited options, Count Vincenz traveled to Paris in 1493 to buy Karl von Geldern, who was being held hostage, free . Since his available funds were insufficient for this, he also exchanged his grandson Bernhard for Karl von Geldern as a hostage.

This action by Count Vincenz and his grandson angered the German King Maximilian I , as he demanded the Duchy of Geldern for his ruling house, the Habsburgs . The county of Moers was therefore occupied by the king's troops and Count Vincenz had to flee again. In order not to finally lose the county for his family, Count Vincenz passed it on to his granddaughter's husband, Count Wilhelm III. von Wied and withdrew to Cologne. Count Wilhelm von Wied had married Count Vincenz's granddaughter, Margarete, Bernhard von Moers' sister, in 1488. Since the king's anger also affected Bernhard, who was held hostage because of the hostage exchange, Bernhard could not be appointed as heir at this time.

The count Vincenz von Moers mentioned in the list of the counting counts was, as already mentioned, not the last male member of the count's family. Vincenz's son entitled to inheritance, named Friedrich , died before his father and his resignation from the office of count in 1493. However, this Friedrich already had a son, the above-mentioned grandson Bernhard . From 1493 he was in Paris as a representative for the Duke of Geldern as a hostage. After the outstanding ransom had been paid in full in mid-1500, Bernhard was released by the French.

After Count Vincenz died in Cologne in 1499, some members of the noble house "von Moers" tried to oust Count Wilhelm von Wied from the county of Moers. In 1500, Johann von Saar Werden , one of Frederick IV's grandchildren , asked to be installed as acting count. He justified his claims with the will of Frederick III. from Moers . It was specified here that only the “male line” could be taken into account in the succession. Since Johann von Saar Werden was in the service of Maximilian I, a positive loan from him could not be ruled out.

At the same time, however, Bernhard von Moers , who was released from hostage, also demanded to be reinstated in his inheritance. Bernhard protested against his "disinheritance" while in captivity. After his release he moved to Moers with mercenaries who had been made available to him by the city of Wesel and the Duchy of Geldern and demanded access to the city. At this point in time, "Wied" troops were stationed in the Grafenschloss, as Count Wilhelm von Wied was still the incumbent count in the county, but was staying in Cracau Castle at that time . In contrast, the Count's wife, Margarete von Wied and Moers , was in Moers Castle at this time. The troops stationed in the castle were not ready to hand over the count's property, protected by ramparts and moats, without a fight and were able to prevent the handover for three weeks. After fleeing Margaret and the expulsion of re Moerser Bernhard von Moers worshiped.

Bernhard now turned to the German king and asked to be reinstated in his rights as Count von Moers. In the meantime, he had agreed with his cousin Johann von Saar Werden that he should be his successor if he himself died without a successor. Before the king could decide on Bernhard's request, he was poisoned in July 1501 during a visit to the court of the Duchy of Geldern. The last direct male member of the von Moers dynasty who could assert well-founded inheritance claims died.

Coat of arms of the Counts of Moers

The family coat of arms of the Counts of Moers shows a black bar in gold ; on the helmet with black and gold covers a male body marked like the shield .

Time after the Counts of Moers until 1600

As of 1493, the county of Moers fell to the county of Wied , as the German king opposed the takeover by Wilhelm III. von Wied as the husband of Magarete von Moers did not raise any objections. After taking over the county, Wilhelm III. give up parts of the previous acquis due to the high level of debt. In 1494 he therefore ceded the castle, castles and land of Dülken, Dahlem, Benrath and Süchteln, which had belonged to the county as pledges for some time, as repayment of part of the debt to the Duke of Jülich-Berg . In addition, the city and state of Wassenberg and the cities, castles and states of Brun, Sittard and Susteren were returned at the same time against reimbursement of the pledge sums and an additional payment of 24,000 guilders.

When the abdicated Vincenz died in 1499, Count Wilhelm III. the county did not hold and had to retire for a few years from 1500. This was followed by Johann von Saar Werden, a second grandson of Friedrich IV, as the next Count of Moers. This had the support of both the Archbishop of Cologne, Hermann von Hessen , and the German king . With this support another change of the reigning noble house was achieved for the succession and the house of Wied was passed over in the line of succession for a few years.

Johann von Saar Werden died childless in 1507, and his brother Jacob von Saar Werden took over the inheritance at short notice. However, he could not keep the county long, because after the death of his brother Wilhelm III. von Wied again claimed his successor. William III. sued the Cologne cathedral chapter for reinstatement. The lawsuit was accepted by the cathedral chapter, but Jacob von Saar Werden did not recognize his jurisdiction over this lawsuit. William III. however, he had an influential supporter in the Duke of Jülich-Kleve-Berg for his claim to the county of Moers, who also gave him military aid. The city of Moers was besieged and conquered on September 14, 1510 by the united troops of the "Wieders" and his ally. Jacob von Saar Werden had to flee and the county of Wilhelm III. left. 1515 was Wilhelm III. von Wied recognized again as the incumbent Count of Moers by Maximilian I , who had meanwhile been crowned emperor ; with this, the Saar werden house was also formally legally replaced.

It followed in 1519 Wilhelm II von Neuenahr , since Wilhelm III. resigned prematurely as acting count in favor of his son-in-law. Wilhelm II had married the daughter of Wilhelm von Wied, Anna von Wied and Moers , in mid-1518. Moers now fell to the Neuenahr noble house . Wilhelm II of Neuenahr had to recognize Kleve's fiefdom again, because at that time the dukes of Jülich-Kleve-Berg on the left Lower Rhine had considerable influence and the county of Moers could not avoid it. With a comparison between Duke Wilhelm V of Jülich-Kleve-Berg and Count Wilhelm II of Neuenahr and Moers and his son Hermann, the fiefdom of Krefeld, Cracau and the County of Moers was contractually confirmed and sealed in 1541.

When Wilhelm II died in 1552, his son, Hermann von Neuenahr the Younger , became his successor. However, under Hermann von Neuenahr's father, the Nassau-Saarbrücken aristocratic family also made inheritance claims on the County of Moers. These claims were based on the marriage of Catharine von Moers and von Wied with Count Johann Ludwig von Nassau-Saarbrücken . This Catharine was another daughter of Wilhelm III. from Wied. An amicable solution to this dispute could not be achieved and from 1555 both the emperor and the imperial chamber court were appealed for a decision several times. All judgments in the meantime were not recognized by one of the two opponents, so that for decades the dispute continued without a solution and only became irrelevant when the Orange took over power . To make matters worse, the religious disputes that began in the second half of the 16th century, and especially the Eighty Years' War , worsened the general situation for the county of Moers.

Under Count Hermann von Neuenahr -Moers (1553–1578) the Reformation was introduced in 1561 with a new reformed church order. When Hermann von Neuenahr died in 1578, his nephew, Count Adolf von Neuenahr , who had married Hermann's sister Anna Walburga in 1546 , succeeded him as Count von Neuenahr-Moers. In addition to the county of Moers, this also inherited extensive free float of the Alps and the county of Limburg . For the successor to Count Adolf von Neuenahr as Count von Moers, there were disputes with the Duchy of Kleve, which the county demanded back as a "settled fiefdom". In 1579 an agreement was reached. In a settlement, Duke Wilhelm V, on behalf of his wife Anna Walburga, transferred the county of Moers to Count Adolf as a Klever fief for life. In the event of the death of the count's family without children, the county should revert to Kleve.

Under Adolf von Neuenahr , the renovations of Moers Castle, which had begun in 1575, were completed and Calvinism was introduced in the county through a new church order from 1581 . A new court order, three police orders and a bush and wood order for the county followed between 1567 and 1586.

This last male successor from the Neuenahr-Moers noble house was a supporter of the converted Archbishop of Cologne Gebhard I von Waldburg and involved the county in the Truchsessian War . As a general of the Truchsessian troops, he was an opponent of the Spaniards under Alessandro Farnese , who inherited the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza in 1586. Due to the increasing conquests of the Spaniards in the southern Netherlands and in Geldern, Count Adolf's wife Walburga had to flee from Moers to Arnhem in July 1584. Count Adolf became governor of Geldern and Overijssel in 1584 and also of Utrecht from 1585, but he could not stop the Spaniards in the long run.

Under Adolf , Neuss was conquered on May 19, 1585 and the Kamp monastery, which belongs to Kurköln, was destroyed in 1586, but Neuss was taken back by the Spaniards in July 1586. This was followed in August 1586 by the conquest of the county with the city of Moers, which remained occupied by the Spaniards until 1597. From the Spanish occupation in 1586, the county with the city of Moers was part of the Duchy of Jülich. Only Rheinberg, which was a city in the Electorate of Cologne, but was located in the area of areas of the county, was not captured until later in February 1590 by the Electorate of Cologne and Spanish troops.

After the death of Count Adolf on October 7, 1589, who was fatally injured in a powder explosion, his widow Anna Walburga was unable to inherit the county due to the Spanish occupation. She also saw no way to successfully enforce her claim. In the treaty of November 20, 1594, the widow, who was living in exile at the time, transferred the county to her relative, Moritz von Oranien , as the legal heiress and Countess von Moers . He besieged the city in 1597 , was able to take it without a fight and cause the Spaniards to withdraw. Anna Walburga was then able to live in Moers until her death and on February 3, 1598 again confirmed the donation from the county to the Orange people.

Orange period

Just three days after the death of Anna Walburga on May 15, 1600, Moritz von Oranien accepted the donation and claimed the county of Moers. Moritz therefore appointed Jost Wirich von Pelden, called Cloudt, as his deputy and Droste of the county on June 8th . However, Duke Johann Wilhelm von Jülich-Kleve-Berg again raised claims to ownership. Klevian emissaries of the duke therefore proposed the patent for a takeover of ownership of the castle on June 3, 1600 and occupied Moers including the castle. In August 1601 the Orange attacked the castle and drove out the Klevian occupation. Thereupon Moritz of Orange was recognized as their sovereign by the nobility and the estates in Moers on August 12, 1601. After this approval, Moritz took over the county on August 16, 1601, and the 100-year-old rule of Orange began despite the protests of the Klevian councilors . However, the legal successors of the Duchy of Jülich-Kleve-Berg did not waive their legal claims to the county. Duke Wolfgang Wilhelm von Pfalz-Neuburg, for example, carried the title Count von Moers in addition to the titles of the Dukes of Pfalz-Neuburg and Jülich-Berg . The respective ruling Orangeians never had their seat in Moers, but instead appointed Droste as their local governor.

On April 14, 1607, Prince Moritz concluded a neutralization treaty with Archduke Albrecht of Austria for the county of Moers. 3000 karolus guilders had to be paid for the contract . This sum had largely the citizens of the county to raise. The Archduke was Governor General of the southern Netherlands and represented Spanish interests. Since the Archduke also concluded a 12-year neutralization treaty with Prince Moritz in 1609, the armed conflicts between the Spanish and the Dutch were interrupted for this time.

The contract for the county was also valid for the Thirty Years War that broke out in 1618 . Through this, the Orange achieved that the county of Moers was recognized by the warring parties as "neutral". The county with the city of Moers was therefore largely spared from the acts of war and the resulting atrocities until the end of the Thirty Years' War . Only in 1633 and 1639 did imperial troops cross the county in breach of neutrality. Furthermore, during a retreat from the French, imperial troops briefly occupied the village of Homburg, which belongs to the county, in 1642, and this area of the county was pillaged and pillaged.

Moritz von Oranien died in 1625. He was succeeded by his brother Friedrich Heinrich von Oranien . During the time of his rule, the aforementioned incursions into the county by troops of the belligerent powers took place, which did not directly affect the city of Moers, but which significantly worsened the economic situation in the county up to the death of Friedrich Heinrich. When he died in 1647, he was followed by his son Wilhelm II of Orange , who died in 1650.

The last Orange as Count von Moers was Wilhelm III. of Orange , who was born only three days after the death of his father Wilhelm II. The Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg tried to take advantage of this late birth . Immediately after the death of his father-in-law Friedrich Heinrich - he was married to his daughter Louise Henriette - he took possession of the county notarially. The birth of Wilhelm III. but ended this attempt and the county remained with the Orange.

Although the Orange were the rulers of the county, the heirs of the formerly united duchies Jülich, Kleve and Berg tried to maintain their old claim to ownership. In the Treaty of Kleve , which ended the inheritance disputes over the united duchies in 1666, the elector of Brandenburg was confirmed to be responsible for the duchy of Kleve and the county of Moers.

When Wilhelm III. died childless on March 19, 1702, the county of Moers was transferred to Brandenburg- Prussia by virtue of an older inheritance and feudal claim as a principality . The basis of this claim to ownership was the already mentioned marriage of Luise Henriette von Oranien with the Great Elector, through which the Brandenburgers acquired a right to the county of Moers through an inheritable kunklee . Only the son of the Great Elector, Friedrich III. von Brandenburg , had the opportunity at the beginning of the 18th century to claim this fief from the Orange with the prospect of success. Since Friedrich III. represented the Habsburg claims in the War of the Spanish Succession from 1701 , he realized this inheritance claim together with the royal dignity ; he was crowned king "in" Prussia and received the support of Emperor Leopold I for both .

Takeover of the county by the Prussians

After the death of the Orange William III. On March 19, 1702, who had no children, the Prussian King Friedrich I saw an opportunity to realize his inheritance claim to the County of Moers. This was derived from the mother of Frederick I, Princess Henriette of Orange , whose father had ordered the inheritance claim in his will. The claim to the county of Moers, together with the claim to the county of Lingen, had already been expressly confirmed by the emperor in 1700.

The secret government councilor Hymmen , who had already been instructed by the Prussian court after he had become aware of the illness, was sent to the county and city of Moers with two notaries from Kleve in response to the news of the Oranian's death. On March 25, 1702, they posted the Prussian coat of arms on the town hall and castle in Moers as a symbol of the takeover of power. The same thing happened in all the churches of important localities in the county. This takeover of power was recognized by the drosten of the county, the Baron von Kinsky, provided that the seizure of possession would not result in any disadvantages to the States General and the rights of third parties .

In contrast, the city council and the citizens of Moers, including many pastors in the county, were not ready for this. You looked at the Wilhelm III. Johann Wilhelm Friso appointed the universal heir as his rightful successor. Because of his youth, however, his mother Princess Amalie took over the reign at this time.

Even the Dutch were unwilling to recognize the assumption of office by the Prussians. A Dutch regiment with four companies was stationed in the fortress under the governor Hieronymus van Sonneren van Vryenesse. The commander's superior was the Dutch commander-in-chief, Prince Walrad von Nassau-Saarbrücken, who claimed the county as part of the Nassau county of Saar Werden and assumed that the government in The Hague would support this. In fact, the Dutch troops were not withdrawn from the county and fortress of Moers and the States General insisted on their jurisdiction.

However, with the death of Wilhelm III. the 2nd period without governor in the Netherlands, which facilitated the transition from the Orange to the Prussians. Although the Imperial Court of Justice recognized the legality of the seizure on May 8, 1702, the complete takeover of power by the Prussians was delayed by more than 10 years.

Since Prussian troops fought against the French at the same time as the Dutch in the War of the Spanish Succession , the Prussians initially did not want to enforce their claim to possession by force and therefore tried diplomacy first. However, due to the stubborn resistance of the Dutch, this did not lead to any result. Only Krefeld could be occupied by a ruse on February 3, 1703 and recognized the Drosten Baron von Kinsky and thus the Prussians as their head. Until the final clarification of responsibilities in the county, Krefeld was therefore the administrative seat of Drosten von Kinsky and the seat of the main court. Another disadvantage for the Prussians was that in the first years from 1702 Prussian soldiers in the outskirts of the county confiscated food and money through violent raids and harassed the residents. This inevitably damaged the Prussian reputation and supported the inclination in the county to reject a change of authority.

In order to improve the situation in favor of the Prussians, King Friedrich I transferred the county to Emperor Joseph I as a Klevian fief. Then the county was elevated to the Principality of Moers by the Emperor in 1707 . With this, the previous county was formally recognized as a Klevian fiefdom. As the Principality of Moers, the former county belonged to Prussia until the French took over the left Lower Rhine in 1794.

For further history: see the main article Principality of Moers

The history of the Moers Fortress

Fortification in the late Middle Ages

The old town of Moers was already fortified before 1586 (before the time of the Spaniards and the Orange people who followed), but it was surrounded by simple circular walls reinforced with towers and a double moat according to medieval construction. Such walls with a rampart provided the main battle position at a time when throwing machines and stone balls (ballistae) were still under siege. They also offered protection against wall breakers and rams.

The inner ditch was separated from the outer by a line concentrically following the arch of the curtain wall. The outer wall was lower than the inner one, and the trench between them was called the "Zwinger". In times of peace, the kennel was allowed to dry out and it served as a practice and battleground for jousting games. In old maps, the area is referred to as "the Renn" (the racetrack). The castle and its immediate surroundings were already surrounded by bastion-like buildings in the late Middle Ages; they formed an island in the Moersbach Lake, connected to the old town by a footbridge. The old town, resembling a semicircle, was separated from the (then) square new town by the "sea", a lake-like widening of the Moersbach, which covered the entire area of today's Neumarkt . Unlike the old town with the curtain wall, the new town was fixed with round bastions on the corners. After the advent of firearms, especially cannons, the type of old town fortification no longer met the requirements for an effective defense. The walls could be hit and destroyed from a great distance; they themselves were also too narrow to place guns.

Because the defenses came from the Middle Ages and were therefore no longer up-to-date, both Bernhard von Moers 1501 and Wilhelm III. von Wied quickly took over the castle in the first case and the town and castle in the second without long resistance. In both cases, the attackers were adequately equipped with wall-breaking cannons.

Fortification by the Spaniards

Between 1586 and 1597 the fortification was redesigned by the Spaniards, who had established themselves in Moers at that time and whose governor Camillus apparently thought of keeping Moers in the long term. He had the outer wall reinforced by a rampart on the city side, from which a certain gun defense was given, while the inner high wall was responsible for close defense. The Neustadt also experienced some innovations: the round bastions were replaced by angular bulwarks that were easier to see for the defenders.

However, at the end of the 16th century, the extended protective systems that the Spaniards had built did not yet correspond to the extent necessary to withstand an attacker adequately equipped with cannons for a long time. Moritz von Oranien therefore had no problems in forcing first the Spaniards and then the defenders from Kleve to withdraw without major fighting both in 1597 and 1601. With the existing wall-breaking equipment of the Orange, no promising long-term defense of the still relatively weak fortifications was possible.

Landwehr and "Buytendorp"

The Landwehr ditch, which was built in the Middle Ages, was used to defend and absorb sewage. He moved around the old town at some distance on the south, east and north sides in a flat arc, branching off from Moersbach at the southern corner of today's Stadtgarten and - running in the area of today's Landwehrstraße - about 3 km north, shortly before Fünderich, again bumping into the Moersbach in a meadow. In the center of this "island location" - created by the arch of the Landwehrgraben - was the parish church of Moers at that time, the Bonifatiuskirche, outside the city fortifications, around the place where the cemetery chapel of the old cemetery on Rheinberger Straße is today. The houses around this "Kerkvelt" are called "Buytendorp" (outer village) in old maps. The Moers historian Hermann Boschheidgen assumes in his description published in 1917 that this upstream village around the old church was the actual original settlement of the early Middle Ages, from which today's Moers later developed - south of it.

The Orange Fortification

The fortifications still visible in large areas of the city today go back to the Orange people. Countess Walburga gave the town and county to her nephew, Prince Moritz of Nassau-Orange, while she was still alive, in the hope that he would “liberate” the town, which had been occupied by the Spanish since 1586 - which was also the case on September 2nd, 1597 actually occurred. Walburga was able to return from her exile; it achieved neutrality for Moers through skilful policy both with the governor of the Spanish Netherlands, Archduke Albert, and with the States General. In her will she designated Prince Moritz as her heir. Although Clevish troops briefly occupied Moers (to enforce old feudal claims), Moritz finally took possession of Moers by force of arms in August 1601. Immediately he set about renewing the fortifications of the castle and town - also the fortification of Krefeld, which belongs to the county, with Crakau Castle. He also took possession of the so-called “Moersische Strasse” with the Papenburg in the glory of Hüls for Orange.

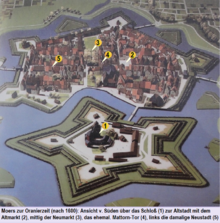

The fortifications around Moers Castle (the Casteel) were provided with five new bulwarks and the old and new towns were surrounded by a ring of fortifications - after a destructive conflagration in the old town on July 25, 1605, the cause of which was never clarified . The so-called Blaeu Plan from 1649 shows a fairly precise representation of the fortifications at that time: It shows a plan broken down into three parts, with a clear separation of town and castle, a five-sided citadel in the middle and nine ravelins around the castle and town around. It was a typical “Dutch” fortress, characterized by acute-angled bulwarks of great depth, the central bulwark as a forward ravelin (crescent moon). The city moat followed the shape of the bulwark. Thanks to the position of the swamp, no large amounts of earth had to be moved in order to fill the trenches with water (from the Moersbach and with groundwater).

The Prussians lay down the bulwarks

After the county had become a Prussian principality, Frederick II had the fortifications “razed” in 1763/1764, as they no longer offered effective protection in the (then) “modern” warfare and their maintenance was too expensive. However, the decision was made not to completely fill the trenches because this would have led to sewage problems. When the Rhine was flooded, Rhine water also penetrated as far as Moers, which is why it was advisable not to completely remove the dams and ramparts. These measures meant that the former course of the fortress is still largely recognizable in the cityscape today.

Reigning Count of Moers until 1702

Note →

| Surname | Term of office | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original line of the Counts of Moers | |||

| (Wilhelm von Moers) | Become abbot of the abbey from 1152 to 1160 | ||

| Dietrich I. | Late 12th century | listed as Theodericus de Murse with brother Elgerus in a document from 1186 | |

| Dietrich I./II. | Early 13th century | Son of Dietrich I, documented in 1226 as Count Dietrich I, † around 1240 | |

| Dietrich II./III. | 1241 to 1268 | Son of Dietrich II. | |

| Dietrich III./IV. | second half of the 13th century | Son of Dietrich III, documented evidence of 1274 and 1289 | |

| Dietrich IV./V. | 1295 to 1346 | Son of Dietrich IV. | |

| Friedrich I. | 1346 to 1356 | Son of Dietrich IV. | |

| Dietrich VI. | 1356 to 1372 | Son of Dietrich V. | |

| Friedrich II./III. | 1372 to 1418 | Son of the brother of Friedrich I., through his wife also Count von Saar Werden | |

| Friedrich III./IV. | 1418 to 1448 | eldest son of Friedrich III .; the younger brother Johann von Moers inherited the county of Saar Werden | |

| Vincenz | 1448 to 1493 | † 1499, son of Friedrich IV., Abdicated in 1493 in favor of the husband of his granddaughter (Count Wilhelm III. Zu Wied-Runkel) | |

| Bernhard von Moers | † 1501, grandson of Vincent, who was held hostage until 1500 and could not take over the county; At the instigation of the grandfather, the Duke of Geldern, who had been taken hostage in France, was exchanged for his grandson Bernhard in 1493 | ||

| From the noble houses of Wied-Runkel-Moers and Moers-Saar | |||

| William III. to Wied-Runkel | 1493 to 1500 | Husband of the granddaughter Magarete of Count Vincenz von Moers | |

| Johann von Saar Werden | 1500 to 1507 | Grandson of Friedrich IV. Von Moers | |

| Jacob von Saar Werden | 1507 to 1510 | Brother of Johann von Saar Werden | |

| William III. to Wied-Runkel | 1510 to 1519 | Jacob von Saar Werden 1510 had to be in favor of Wilhelm III. resign to Wied, who was thus again acting count | |

| From the noble house of Neuenahr-Moers | |||

| Wilhelm II of Neuenahr | 1519 to 1553 | Husband of Anna, daughter of Wilhelm III., Count zu Wied-Runkel (according to the marriage contract, the son-in-law becomes Count von Moers from 1519, but renounces an inheritance from Wied-Runkel) | |

| Hermann von Neuenahr the Younger | 1553 to 1579 | Son of Wilhelm II von Neuenahr | |

| Adolf von Neuenahr | 1579 to 1589 | Husband of Anna Walburga, sister of Hermann von Neuenahr the Younger | |

| Anna Walburga von Neuenahr | 1589 to 1600 | Daughter of Hermann von Neuenahr the Younger, Countess von Moers, was only able to officiate in Moers from 1597, as the county was occupied by Spanish troops up to that point | |

| From the noble house of the Orange | |||

| Moritz | 1600/1601 to 1625 | Anna Walburga had given the county of Moers to her relative Moritz von Oranien in 1594 | |

| Friedrich Heinrich | 1625 to 1647 | his daughter Luise Henriette married the Great Elector of Brandenburg, thereby entitling the Prussians to the county as a kunkellehen | |

| Wilhelm II. | 1647 to 1650 | his will enabled the descendants of Luise Henriette to have an inheritance claim if his son Wilhelm III. should die without offspring | |

| William III. | 1650 to 1702 | last Orange, then Brandenburg-Prussia took over the county of Moers | |

economy

Until the middle of the 17th century, the county's residents were mainly active in agriculture. In addition, a smaller proportion of the residents worked as craftsmen in the service areas required at the time. In the two cities of Moers and Krefeld there were craftsmen in large numbers. But even these produced almost exclusively for local needs. The craftsmen were organized in guilds. The oldest "official or guild letter" that can be traced in Moers dates from 1453 and concerns the shoemaker. Verifiable guilds around 1750 were: bakers, joiners, carpenters together with turners and glaziers, thread and line weavers and blacksmiths. The distribution of the goods of potters and weavers who made goods beyond their own needs was only limited to the surrounding area. In addition to the organized craftsmen, there were masters who operated their trade without a guild. This also included beer brewers, grain and brandy distillers and goldsmiths.

The products were mainly sold on the city markets approved by the authorities in Krefeld and Moers. These weekly markets were allowed to be held one day a week. In addition to these market days, there were a few days of the year on which annual markets were permitted. With additional long-distance trade in textiles, the first small weaving mills began in Krefeld around the middle of the 18th century.

In a wide strip from Hüls in the south to Moyland in the north on the left Lower Rhine near the surface there was good quality clay that was suitable for pottery and that was mined. Already around 500 BC There is evidence of pottery in the Hülserberg area. In the county was the center for the production of pottery products such as roof tiles, wall panels and pottery between Hülserberg with Vluyn and Rayen with Schaephysen. The heyday of pottery in this area was the 17th to 19th centuries.

In addition to pottery, the cultivation of flax and the production of linen was an old and widespread craft. The production of linen was mainly limited to own and local needs. This changed with the Orange. After the mid-16th century, the Mennonites were persecuted and driven out of the Catholic areas of the empire . As the county became a Protestant area towards the end of this century, the first religious refugees came at this time. The Reformed Dutch, as Protestants, also allowed these persecuted people to settle in the areas they controlled.

With the beginning of the rule of the Orange, more Mennonites settled in Krefeld. Among these was Adolf von der Leyen with his family, who had to leave the Duchy of Berg as Mennonites and were granted civil rights in Krefeld in 1679. Thanks to the Mennonites, many of whom were weavers, Krefeld developed into a center for linen weavers on the Lower Rhine. By the end of the 17th century, more than a third of the people of Krefeld were employed in the textile industry. In addition to the linen goods, cotton products were also started to be produced, as they had to compete with cheap Irish cotton goods.

In addition to linen weavers, these new residents included the von der Leyen family , who were trimmings and traders and who were soon selling these products from Krefeld. When the Prussians took over government in the Principality, members of the von der Leyen family began to manufacture silk goods as well as the already existing production of linen and cotton goods. In 1720 Peter von der Leyen founded the first sewing silk company in Krefeld. It followed in 1721 the production of silk ribbon and velvet goods by Friedrich and his half-brother Johann von der Leyen , which was expanded in 1724 with the dyeing of silk goods.

After Johann's death in 1730, Adolf von der Leyen Friedrich and Heinrich's grandchildren founded a new joint silk company. This received from the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm I duty exemption for the import of the necessary raw materials and no excise duty on the finished goods. However, these exemptions only applied to areas west of the Weser, as the Berlin textile industry was also supported. The successor King Friedrich II also granted the monopoly for the manufacture of silk fabrics.

The production of goods made of silk in Krefeld developed very favorably thanks to the monopoly for the von der Leyens . The percentage of Krefelder employed in the up-and-coming textile industry rose to over 50% around the middle of the 18th century. For example, in 1765 von der Leyens operated 15 twist mills with 300 workers and 100 belt mills with 1000 workers and 500 looms. The fabric production was mainly carried out in home work by former linen weavers throughout the territory of the principality. The companies provided the necessary looms for the do-it-yourselfers. The wages for working from home to produce the silk fabrics were low. A journeyman earned only 30 to 50 silver groschen a week. The very cost-effective production of silk fabrics thanks to home weaving led to market leadership beyond the Lower Rhine within a few decades.

The von der Leyen family soon became one of the richest in the Rhineland. The city of Krefeld developed in line with the flourishing textile industry and gained the reputation of a “ velvet and silk city”. In addition to the von der Leyens, there were 12 other manufacturers in 1787, for example the Floh and de Greif families with their companies that made silk products. At this time, 703 looms were in operation in Krefeld, to which many were added in the surrounding area. In the city of Moers alone, an additional 76 chairs were in use. The total value of the silk goods was 750,000 Klever Reichsthaler per year. Goods worth more than 600,000 Reichsthalers were exported beyond the region and over two thirds went to overseas and America.

Although in the French period the contacts of the family von der Leyen to the French authorities as before were also good for the Prussian royal house, their monopoly for the production of silk products was lifted and there arose many rival companies both in the former Principality and beyond its borders in other Prussian territories. At the time of the legal end of the county or principality in 1801, there was a flourishing textile industry in addition to agriculture, which produced goods from linen, cotton and silk.

Culture

The traditional costume of women in Grafschaft has been handed down to this day.

Web links

- Moers city history , short table version

- City archive Moers

- nbn-resolving.de Digitized edition of the "History of the County of Moers" by Carl Hirschberg

literature

- Hermann Altgelt : History of the Counts and Lords of Moers. Düsseldorf 1845.

- Karl Hirschberg: Historical journey through the county of Moers from Roman times to the turn of the century , Verlag Steiger, Moers 1975

- Gerhard Köbler : Historical lexicon of the German countries. The German territories and imperial immediate families from the Middle Ages to the present. 5th, completely revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39858-8 .

- Theodor Joseph Lacomblet: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cöln, the principalities of Jülich and Berg, Geldern, Meurs, Cleve and Mark, and the imperial monasteries of Elten, Essen and Werden. From the sources in the Royal Provincial Archives in Düsseldorf and in the provincial church and city archives, Volume 4, J. Wolf, 1858.

- Guido Rotthoff: To the early generations of the Lords and Counts of Moers. In: Annals of the Historical Association for the Lower Rhine. (AnnHVNdrh) 200, 1997, pp. 9-22.

- Margret Wensky: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. In: From the Prussian period to the present. Volume 2, 2000, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna. ISBN 3-412-04600-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Gerhard Köbler: Historical Lexicon of the German Lands. The German territories and imperial immediate families from the Middle Ages to the present. 5th, completely revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39858-8 , p. 390.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 1, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , pp. 63-68.

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers. 2nd Edition. 1904, p. [20] 14 ( digitized edition of the ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ^ Günther Eckhard, in: Die Dorfkirche von Repelen , in a printed information sheet that is publicly available in the church.

- ^ Hermann Altgelt, in: History of the Counts and Lords of Moers , 1845, p. [19] 5.

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers , 2nd edition. 1904, p. [28] 22 ( digitized edition of ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 1, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , pp. 9, 98.

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: Geschichte der Grafschaft Moers , 1904, p. [11]. (Online version)

- ↑ a b Peter Caulmanns, in: Neukirchen-Vluyn: his story from the beginnings to the present. Michael Schiffer Verlag, 1968, p. 28.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 1, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , p. 73.

- ↑ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Urkundenbuch / Urkunde No. 138 , 1846, Volume 2, p. [112] 74 ( digitized edition of the ULB Bonn ).

- ^ Hermann Altgelt, in: History of the Counts and Lords of Moers. 1845, p. [20] 6, [23] 9.

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the county of Moers. 2nd Edition. 1904, p. [28] 22 ( digitized edition of ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers , 2nd edition. 1904, p. [40] 34, [48] 42 ( digitized edition of the ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cöln, Document 625. 1853, Part 3, 1301–1400, p. [539] 527.

- ↑ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, certificate 67. 1858, part 4, p. [100] 74 ( online edition 2009 ).

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, document 160. 1853, part 3, 1301–1400, p. [139] 119.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 1, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , p. 80.

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, Certificate 709. 1853, Part 3, 1301–1400, p. [619] 607.

- ↑ H. v. Eicken, in: On the history of the city of Ruhrort / magazine of the Bergisches Geschichtverein. 1882, Book No. 17, p. 2. (online version).

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, document 721. 1853, part 3, 1301–1400, p. [628] 616.

- ↑ a b c H. v. Eicken, in: On the history of the city of Ruhrort / magazine of the Bergisches Geschichtverein , 1882, book no. 17, p. 3. Online version

- ↑ H. v. Eicken, in: On the history of the city of Ruhrort / magazine of the Bergisches Geschichtverein. 1882, Book No. 17, p. 4 (online version).

- ↑ Lacomblet Th. J .: "Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cologne". In: Comments on the certificate 709. 1853, volume 3, p. [619] 607 ( digitized edition ULB Bonn ).

- ↑ H. v. Eicken, in: On the history of the city of Ruhrort / magazine of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein. 1882, Book No. 17, p. 5 (online version).

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, certificate 750. 1853, part 3, 1301–1400, p. [657] 648.

- ↑ Ralf G. Jahn, in: Chronicle of the County and the Duchy of Geldern. 2001, edited by Johannes Stinner and Karl-Heinz Tekath, part 1, p. 501.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers, The history of the city from the early days to the present. 2000, Volume 1, Böhlau Verlag, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , p. 93.

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers. 2nd Edition. 1904, pp. [59] 53– [65] 59 ( digitized edition of the ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ↑ Lacomblet, Theodor Joseph: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, document 409. Volume 4, 1858, p. [533] 507. Online edition 2009 [1]

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers. 2nd Edition. 1904, p. [65] 59 ( digitized edition of ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ↑ Lacomblet, Theodor Joseph: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, document 458. Volume 4, 1858, p. [594] 568. Online edition 2009 [2]

- ^ Hermann Altgelt, in: History of the Counts and Lords of Moers. 1845, p. [96] 82 (online version).

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers. 2nd Edition. 1904, p. [66] 60 ( digitized edition of ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ↑ a b Herrmann Altgelt, in: History of the Counts and Lords of Moers. 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, pp. [96–97] 82–83.

- ↑ a b Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 1, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , p. 160.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 1, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , pp. 160-163.

- ^ Bernhard Peter: Gallery: Photos of beautiful old coats of arms No. 12 , coat of arms at Weilburg Castle, 1st part

- ↑ Lacomblet, Theodor Joseph: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine and the Archbishopric of Cöln, document 462 with additional notes. Volume 4, 1858, pp. [598] 572. Online edition 2009 [3]

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: History of the Counts and Lords of Moers. 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [96] 82.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 1, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , pp. 164-165.

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: History of the Counts and Lords of Moers. 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, pp. [97] 83– [99] 85.

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cöln, 1401–1609, document 541 . Volume 4, 1858, pp. [695] 669. Online version

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: History of the Counts and Lords of Moers. 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [108] 94.

- ↑ a b c d NDB, under: Adolf von Neuenahr , 1999, Volume 19, pp. 109, 110.

- ^ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, in: Document book for the history of the Lower Rhine or the Archbishopric of Cöln, 1401–1609, document 582 . Volume 4, 1858, p. [752] 626. Online version

- ^ Max Cossen, in: The Cologne War , 1897, p. [649] 629 (online version).

- ↑ a b Max Lossen, in: The Cologne War. 1897, p. [654] 634 (online version).

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Family and History, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers. 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [207] 193.

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers. 2nd Edition. 1904, p. [40] 34, [112] 106 ( digitized edition of the ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers, History from early times to the present. Volume 1, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2000, p. 271.

- ↑ a b Peter Caulmanns, in: Neukirchen-Vluyn: his story from the beginnings to the present. Verlag Michael Schiffer, 1968, p. 45.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers, History from early times to the present. Volume 1, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2000, p. 272.

- ↑ City Archives State Capital Düsseldorf, in: Certificate 0-2-1-132.0000 .

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers. 2nd Edition. 1904, p. [116] 110 ( digitized edition of ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers, History from early times to the present. Volume 1, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2000, p. 276.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers, History from early times to the present. Volume 1, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2000, pp. 275-277.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers, History from early times to the present. Volume 1, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2000, p. 277.

- ↑ Adalbert Natorp, in: Lecture: History of the Evangelical Community in Düsseldorf , Voss, 1881, p. [44] 40 ( digitized edition of the ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ^ Rheinische Post, in: Article about: Luise Henriette von Oranien , October 11, 2011.

- ↑ a b Margret Wensky: In: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present . Volume 2, 2000, Böhlau Verlag, p. 1, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 .

- ↑ Margret Wensky: In: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present . Volume 2, 2000, Böhlau Verlag, p. 2. ISBN 3-412-04600-0

- ↑ Ernst von Schaumburg , in: King Friederich I and the Lower Rhine , 1879, p. [135] 185.

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers , 2nd edition. 1904, p. [144] 138 ( digitized edition of ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers , 2nd edition. 1904, p. [145] 139 ( digitized edition of ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ↑ Peter Caulmanns, in: Neukirchen-Vluyn: his story from the beginnings to the present. Michael Schiffer Verlag, 1968, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Margret Wensky: In: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present . Volume 2, 2000, Böhlau Verlag, p. 4. ISBN 3-412-04600-0

- ^ Hermann Boschheidgen: The Oranische and Vororanische fortification of Moers. Steiger Verlag, Moers 1917/1979, ISBN 3-921564-17-4 , p. 11

- ^ Hermann Boschheidgen: The Oranische and Vororanische fortification of Moers. Steiger Verlag, Moers 1917/1979, ISBN 3-921564-17-4 , p. 15

- ^ Hermann Boschheidgen: The Oranische and Vororanische fortification of Moers. Steiger Verlag, Moers 1917/1979, ISBN 3-921564-17-4 , p. 23

- ^ Hermann Boschheidgen: The Oranische and Vororanische fortification of Moers. Steiger Verlag, Moers 1917/1979, ISBN 3-921564-17-4 , p. 27

- ^ Hermann Boschheidgen: The Oranische and Vororanische fortification of Moers. Steiger Verlag, Moers 1917/1979, ISBN 3-921564-17-4 , p. 27

- ^ Hermann Boschheidgen: The Oranische and Vororanische fortification of Moers. Steiger Verlag, Moers 1917/1979, ISBN 3-921564-17-4 , p. 114

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Family and History, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [29] 15.

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Familie und Geschichte, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [41] 27.

- ^ Carl Hirschberg, in: History of the County of Moers , 2nd edition. 1904, p. [65] 59 ( digitized edition of ULB Düsseldorf ).

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Family and History, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [88] 74.

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Family and History, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [96] 82.

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Family and History, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [96] 82.

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Familie und Geschichte, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [98] 84.

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Familie und Geschichte, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [99] 85.

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Family and History, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [196] 92.

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Familie und Geschichte, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [159] 145.

- ^ Herrmann Altgelt, in: Familie und Geschichte, Grafschaft Moers 1160–1600 Moers , 1845, digitized version of the University of Düsseldorf, p. [199] 185.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 1, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , p. 247.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 2, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , pp. 94-101.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 1, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , p. 241.

- ↑ Margret Wensky, in: Moers The history of the city from the early days to the present. Volume 2, Verlag Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-04600-0 , p. 101.

- ↑ Peter Caulmanns, in: Neukirchen-Vluyn his story from the beginning to the present. Michael Schiffer Verlag, Rheinberg 1968, p. 51.

- ↑ a b c d Helmuth Croon: von der Leyen, Friedrich. In: New German Biography. 14 (1985), p. 432 f. [4]

- ↑ Peter Caulmanns, in: Neukirchen-Vluyn his story from the beginning to the present. Verlag Michael Schiffer, Rheinberg 1968, p. 78.

- ↑ a b c Peter Caulmanns, in: Neukirchen-Vluyn his story from the beginning to the present. Verlag Michael Schiffer, Rheinberg 1968, p. 79.

- ^ Johann Georg von Viebahn (ed.): Statistics and topography of the government district of Düsseldorf. second part, Düsseldorf 1836, p. 170.

- ^ Johann Georg von Viebahn (ed.): Statistics and topography of the government district of Düsseldorf. second part, Düsseldorf 1836, pp. 169 + 170

-

↑ Marga Knüfermann: The Grafschafter costume. County of Moers. In: Heimatkalender des Kreis Wesel 8 (1987), pp. 138-142, Ill.

Marga Knüfermann: Die Grafschafter Tracht. Grafschaft Moers II. In: Heimatkalender des Kreis Wesel 9 (1988), p. 182 f., Ill.

Remarks

- ↑ The fact that Repelen is identical with “Reple” (or also “Replo (e)”) cannot be proven. Current historians are of the opinion that the manor was not in Repelen, but in "Reppel" in North Brabant. Proof: Margret Wensky, 2000, Volume 1, History of the City of Moers, pp. 126/7.

- ^ Friedrich IV. Received these areas as "pledges" in 1421 from Rainald von Jülich-Geldern. In 1423 these pledges were confirmed by Adolf VII von Berg and his co-heirs after another payment. In June 1494 Wilhelm von Jülich-Berg released these pledges (evidence: Hugo Altmann, "Moers", NDB 17, 1994, pp. 680–682). During the negotiations for the Treaty of Venlo in 1543, Wilhelm II. Von Neuenahr waived the rights from these former pledges (evidence: Hermann Altgelt: Geschichte der Grafen von Moers, 1845, p. [101] 87).

- ↑ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet cites January 1, 1287 as the date of January 1, 1287 in document 834 for the sale of the "Werden" in the "Document Book for the History of the Lower Rhine or the Archdiocese of Cologne."

- ↑ Because of the incomplete data, there are different counting methods for both the "Friedrichs" and the "Dietrichs". The listed Friedrich I is also counted by some historians as Friedrich II.

- ↑ In the 14th century the course of the Rhine in the area of the mouth of the Ruhr had shifted considerably. As a result, the former “Homberger Werth” peninsula was no longer on the left, but on the right of the Rhine. Since the right bank of the Rhine belonged to the County of Kleve, the Counts of Kleve and von der Mark had lodged an objection to the sole customs law for the Moerser.

- ↑ Count Vincenz had a second son Dietrich, who also died early, in addition to Friedrich. This in turn had two sons, Christoph and Dietrich. However, this had excluded Vincenz from an inheritance.

- ↑ Maximilian I was only crowned emperor a few years later. Furthermore, the now deceased Bernhard von Moers had named Johann von Saar Werden as his successor in the event of his death.

- ↑ Wilhelm III. von Wied had renounced an inheritance from Wied at the wedding, and Anna was not entitled to inherit for Saar Werden. Wilhelm von Wied lived in Moers until his death around 1530.

- ↑ Adolf received the Alpine property through his father Gumbrecht IV and Limburg through his second wife Amöna von Daun-Falkenstein.

- ↑ By belonging to the "Reformed Faith", the left Lower Rhine was strongly influenced by the political situation and the Dutch state church. In addition, the language of the residents, Kleverländisch , was closely related to Dutch and the use of the Dutch language was widespread until around the middle of the 19th century. In addition, there was a development in the area of the Duchy of Kleve with the Prussian administration that did not correspond to the previous "class conditions" and the so-called "Dutch freedoms" for the administration in the county. (Proof: M. Wensky, book 2nd volume, chapter Moers 1702 to 1815)

- ↑ In the Blaeu plan from 1917, the Bonifatiuskirche is shown in the “Kerkvelt” on the current Rheinberger Strasse north of the old city wall in the area of Mühlenstrasse.

- ↑ The data of the first "Diederichs" and "Friederichs" are incomplete. In the literature, historians cite different dates and counting methods. The data on this list was taken from the book Moers by Margred Wensky from 2000.