History of Western Astrology

The history of western astrology can be traced back in its origins to pre-Christian times in Babylonia or Mesopotamia and Egypt . Astrology learned its basic principles of interpretation and calculation, which are still recognizable today, in the Hellenistic Greek-Egyptian Alexandria . Astronomy emerged from it as a non-meaningful observation and mathematical appraisal of the starry sky, and it remained associated with it for a long time as an auxiliary science.

Astrology had a checkered history in Europe. After Christianity was elevated to the status of the state religion in the Roman Empire , it was partly opposed, partly adapted to Christianity and temporarily sidelined. In the course of the early Middle Ages , astrology, especially learned astronomical astrology, revived in the Byzantine Empire from around the late 8th century, as it did a little later in Muslim Al-Andalus on the Iberian Peninsula . From the later High Middle Ages and especially in the Renaissance up to the 17th century, it was often considered a science in Europe, always connected with astronomy in the quadrivium of the seven liberal arts taught in preparation at universities , even if it was quite controversial. In the course of the Enlightenment , however, it lost its plausibility in educated circles . It was only around 1900 that a serious interest in astrology arose again, often also in the wake of new esoteric currents such as theosophy or the occult fashion from the later 19th century, as a typical and successful representative of this phase in the German-speaking area Karl Brandler-Pracht be valid. Since the late 1960s, based on the New Age movement, it has gained a high degree of popularity in the western hemisphere, mostly in the form of natal charts and sun astrology .

prehistory

It makes sense to distinguish between 'classical' astrology, which was mainly used in the Hellenism and Ptolemaic Empire from the 3rd century BC onwards. BC originated, possibly including cuneiform 'horoscopes', zodiac and planetary calculation ability in the Achaemenid and Seleucid kingdoms (5th / 4th to 1st century BC), and the 'forerunners' of astrology. Preforms in the broadest sense are z. B. Astral cults for the sun , moon , Venus and other celestial bodies including their cult systems and objects, astral mythologies, cult calendars, astral divinations, etc. They were widespread prehistoric and ancient as well as ancient . For example, archaeological finds in Europe over the past few decades have made it clear that there has been a kind of sun cult since the Neolithic . Stone circles such as Stonehenge , according to one of several theories, were used. a. the observation of the constellations and the sun's path with its solstice and equinox . It should also be remembered z. B. to the Nebra Sky Disc , which dates back to about 3000 BC. Dated, the gold hats or the sun chariot from Trundholm and the circular moat from Goseck . The astronomical knowledge and traditions, which are sometimes only presumed, do not seem to be verifiable in Europe beyond the first millennium BC.

Antiquity

Mesopotamia

For the region of Mesopotamia and especially Babylonia , three phases of astronomical-astrological development can be distinguished:

- the omen 'astrology' with a heyday between the 14th and 7th centuries BC Chr.

- the beginnings of a preform astrology with the still incomplete zodiac around the 6th century BC. Chr.

- the first development of an astrological system from the 5th century BC. BC with the twelve signs of the zodiac, calculated planetary positions and omen-like interpretation of individual birth constellations.

The earliest, albeit few indications of astrological divination in the sense of astronomical observations of the sky in the area of Mesopotamia and predictions or omen texts derived from them are initially at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. To be found among the Sumerians , in connection with the intestinal inspection that is customary with them . In the early fortune-telling techniques one finds ideas of benevolent gods who give people encrypted signs for warning and orientation, as well as ideas that the cosmos reacts to human deeds and intentions through signs. On the other hand, with increasing knowledge of the celestial movements, the belief grew that creation was formed by a network of unchangeable cosmic laws that would also determine human life beforehand. The celestial phenomena themselves, which were carefully followed to determine the calendar , were interpreted as favorable or unfavorable e.g. B. for a country or for a ruler, a typical aspect of oral astrology . A large number of such predictions were found in the library of Ashurbanipal in the ruins of Nineveh from the second half of the 7th century BC. In this context, an astral deity was assigned to every day, every month or even individual regions of the Mesopotamian Empire . The moon was then considered to be the highest planetary deity. In the library of Nineveh, copies of the well-known series of clay tablets Enuma Anu Enlil were also found, which probably dates from the end of the 2nd millennium BC. It was created and the celestial signs and their interpretation or rather the associated omen texts were shown on more than 70 large panels.

The complete zodiac with its twelve constellations - still of different lengths - on the ecliptic was finally created in the 5th century BC. Developed or first handed down during the Achaemenid Empire in the area of Mesopotamia. In the 4th century BC During the Seleucid rule after the Hellenistic conquest of the area, the exact division of the zodiac into twelve "signs" at 30 ° as well as the ancient mathematical astronomy, which made it possible to calculate the planetary positions in advance based on the coordinate system of the 30 ° sections of the individual signs of the zodiac . The sidereal zodiac itself with its twelve equal 30 ° sections and the beginning with the zodiac sign Aries could have been created by following the schematic 'ideal calendar' with twelve months to 30 days, with which the Babylonian year near the spring Equinox perhaps from the 7th century BC Began, and was based on the parallel constellations. Both developments made possible another important innovation for astrology and natal chart: the creation of so-called cuneiform 'horoscopes', now also for ordinary people. This means cuneiform tablets which list the planetary positions in the zodiac at birth, occasionally with short sayings about the individual planets or the planetary constellations, the omina. A few times the exact positions of the planets in the zodiac signs are also given. Horoscopes in today's sense gave the tablets a. a. therefore not here, because neither the ascendant nor the horoscope houses are named on them.

Eastern Mediterranean

Egypt

In ancient Egypt , as everywhere else, the influences of the stars were initially not related to individual persons. There emerged towards the end of the 3rd millennium BC. As a pre-form of astrology with the dean stars or the 36 dean gods and their movements such as rising and setting on the horizon, a comprehensive evaluation of favorable and unfavorable days. The deans were also used to measure time at night and influenced the timing of cult acts and the choice of building sites for temples. Later z. B. Weather forecasts and birth prophecies derived. A dean extended over an arc of 10 °, so that with the 36 deans the entire sky was divided. The 36 deans were probably established during the 3rd century BC. In Ptolemaic Egypt combined with the 360 ° Babylonian zodiac. This presumably gave rise to the teaching of the 'zodiac dean' rising at birth on the eastern horizon, and soon afterwards of the ascending zodiac degree, the horoscope ascendant .

Judaism

The old Israel was under the influence of Babylonian astrology, by the way, so that predicting the future is in the Tanach but no speech. Although solar and lunar eclipses play a role there in the context of disasters, they are presented as parts of them, not their harbingers. Since the 7th century BC According to the theologian Klaus Koch, polemics against an astral cult can be found in the prophets Amos and Jeremiah , and the religious reforms of Joschiah also suggest that there were astrological practices in Israel. During the time of exile , Deutero-Isaiah sharply condemned astrological practices. According to Kocku von Stuckrad , however, these biblical polemics were not directed against the interpretation of the stars, but against a cultic veneration of the stars.

Altogether, a broad spectrum of attitudes towards astrology can be proven in ancient Judaism, from theologically justified condemnation to enthusiastic approval. During the Seleucid period , astrological signs can even be found in the Jerusalem temple , at the same time the books of Enoch polemicized against astrology. The zodiac signs of the ecliptic are replaced here by twelve "gates of heaven", which have no prognostic or sympathetic meaning for the human world. The purpose of this circle is seen solely in calendar terms to enable the Jews to observe religiously prescribed days. The influence of astrology can again be felt in the prophecies of Dan 8 EU , which are based on astrological geography. Horoscopes were also found in the caves of Qumran , and synagogues from late antiquity were decorated with astrological images. In the Babylonian Talmud , both the position of astrological predestination and the thesis that by following the laws of the Torah the Jews are freed from what is justified with Dtn 4:19 EU is documented.

Greek culture

The Greek culture, which preceded Hellenism and the Roman Empire, took over from around the 6th century BC. Elements of Babylonian astronomy, u. a. Constellations and eclipse calculations. The Babylonian omen astrology and its elements were not taken over. After the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC Many Eastern mystery religions spread in the Hellenistic world. Astrological teachings were often associated with these, although they were initially only cultivated in small circles, as well as in some cases cults of star worship. The emergence of individualistic tendencies opened up the perspective of possible influences of the stars on the individual fate.

The Babylonian priest Berossus brought in the 3rd century BC. Under the influence of Hellenism, the area of Babylon was at that time part of the Hellenistic empires, a history of Babylon that is only indirectly passed down in fragments, to which fragments with a few astrological or cosmological elements are included. Around 300 BC Berossos is said to have settled on the island of Kos and founded the first astrology school of the Hellenistic world there, but this is not considered certain due to the problematic sources. He did not teach natal charts, if at all, as it was taught from the 2nd century BC onwards. In Hellenistic Egypt or in the Egyptian Ptolemaic Empire, especially in Alexandria . In the Berossos research it is noted accordingly that none of the astronomers living after Berossos such as astrologers, such as Hipparchus or Ptolemy , cited or gave a lecture.

In Hellenism, astrology had partly the dignity of a belief and was at the same time partly scientifically founded. In the two centuries before and after the turn of the times, that system of classical astrology developed, especially in Egypt and Alexandria, the components of which are still widely used today. In contrast to its Babylonian predecessors, it took into account many more astronomical and astrological elements, and astrological prediction related even more to individuals and less to peoples and their rulers.

Elements of the classical astrology of the time:

- Babylonian or Achaemenid and Seleucid origin: the twelve signs of the zodiac , exact position of the planets with the sun and moon, planets elevations in certain signs, dodecatemories (division of the signs into sections of 2.5 °), sign triplicities;

- Egyptian origin: concept of 36 deans, with the ascending dean on the eastern horizon, from which the idea of the ascendant developed; The vertical horoscope axis between Medium coeli , the center of the heavens or abbreviated as 'MC', and Imum coeli, the depth of heaven or 'IC', originally from Egyptian astronomy concepts, probably comes from the heavenly segments with special meanings; the astrological interpretations of the horoscope axes and 'places' (= horoscope houses) handed down to this day, however, cannot be traced back to the pre-Hellenistic times of Egypt;

- Greek origin: the four elements , “male” and “female” signs, sign rulership system (e.g. the moon 'rules' over the sign Cancer ), planetary hours ;

- Hellenistic or Alexandrian origin: the twelve horoscope houses , the idea of 'nocturnal' and 'daily' planetary positions in the horoscope, planetary effects in the individual signs and horoscope houses, planetary aspects , the 'pars fortuna' or the 'lucky point', Subdivisions within the signs according to so-called 'limits' and 'faces', the annual solar horoscope, the so-called decumbitur horoscope (horoscope technique for disease prognoses ), an hourly astrological method with the term 'catarche horoscopes' (choice of a astrologically favorable time), as well as the horoscope techniques of the so-called 'profections' and 'lunations'.

Rome

In the Roman Empire , astrology gained great popularity in all classes of the population from the first century AD. Several rulers of the early Roman Empire such as Tiberius and Augustus were also among their followers, as well as Domitian and Trajan . The influence of astrology and of astrologers at the imperial court, however, subsided again in the course of the 2nd century. The conscious or manipulative use of astrology for political or rule-legitimizing purposes in the sphere of the powerful was the inevitable downside of this development, in which 'posed' or invented and appropriately corrected natal charts as well as deliberately false prognoses were used for good and bad This was probably the reason why the expulsion of astrologers from Rome and Italy was repeatedly ordered. This typically included e.g. B. the construction or 'finding' of 'emperor dignities' promising or depicting planetary and horoscope constellations for birth, as it is very likely handed down in the ascendant published in antiquity, probably corrected in the natal chart of the Roman emperor Hadrian . There were also critical voices, including the satirist Lukian of Samosata . The notion that the movements of the planets completely determined the fate of humans was widely considered plausible at the time. With the Syrian cult of Baal and the cult of Mithras, the worship of the stars also spread and combined with astrology. Astrology found a philosophical justification mainly on the basis of the Stoa .

Two extensive compendia of Classical-Hellenistic astrology in Greek have been preserved from the 2nd century. The more important from an occidental point of view was the four-volume Tetrabiblos by Claudius Ptolemy . It was conceived as a systematic textbook on astrology, about the basics in the 1st volume, the Mundana astrology in the 2nd volume and in the 3rd and 4th volume on the natal astrology, i.e. to create a horoscope for the time of the birth of a person and his / her Interpretation. This also included a meticulous classification of the elements of the horoscope: the fixed stars, the planets, the signs of the zodiac and the aspects . However, Ptolemy lacks z. B. the consideration of the horoscope houses, which were already so important at the time, so it seems to follow the Hellenistic-Babylonian or late Babylonian, more Seleucid astrology tradition compared to the “Hellenistic-New Egyptian”. On the other hand, Ptolemy was not active as a practicing astrologer, at least as far as the natal chart is concerned. Accordingly, horoscope examples and natal planetary constellations are completely missing in the Tetrabiblos .

The other compendium are the nine volumes of the Anthologiae by Vettius Valens . This is a textbook mainly on the natal chart, even though it was possible that Valens only put it together over the course of decades from several independent treatises. Like Ptolemy, Valens saw himself as a 'scientist', albeit in a slightly different sense than Ptolemy, as the preface to the 6th book of the Anthologiae makes clear. In contrast to Ptolemy, Valens was again a practicing astrologer, the Anthologiae von Valens with 121 datable example horoscopes, by far the largest corpus of an ancient author. While the Tetrabiblos was considered the standard work in the West for centuries, the Anthologiae were enthusiastically received and disseminated by Arabic astrologers.

Ptolemy's endeavors to formalize and theoretically systematize astrology, or even to make it scientifically based on empirical standards, were quite typical of the first centuries after the turn of the century, in which classical Hellenistic astrology and natal horoscopy, both in terms of content and form, with the creation of astrology textbooks like the Tetrabiblos or the Anthologiae reached a high point in the 2nd century. In the Babylonian or Chaldean direction of astrology, predictions were often combined with religious considerations. On the other hand, Vettius Valens himself emphasized in his anthologiae , despite all the 'empirical' and 'scientific' inclination, the religious dimension of astrology, the wisdom of which should only be reserved for those 'initiated' in the mystical quality of astrology.

Early Christianity and Late Antiquity

Early Christianity found itself in a conflict with astrology because, according to many church teachers, the predestination of fate contradicts free will as an unconditional requirement ( conditio sine qua non ) of the Christian faith , on the other hand an astronomical event with an astrological statement regarding the birth of Christ was connected. It goes without saying that a strong belief in the heavenly bodies was in any case in tension with some central Christian dogmas and beliefs. At the same time, however, astrology was in part strongly taken up in the various Christian currents, especially in the Gnostic , Neoplatonic and Manichaean religious and philosophical movements of late antiquity, which developed in parallel .

The further position of astrology in the public sphere of late Roman antiquity was shaped by several developments. I.a. A divinely derived imperial monopoly of interpretation established itself in increasing numbers, which soon turned against astrology and seerism such as divination , against magic and Manichaeism, etc., probably or precisely because of the possible competition between these world explanations and the imperial monopoly of interpretation. As early as the 3rd century, the non-Christian Emperor Diocletian had banned 'scientific' astrology as part of the seven liberal arts and thus as 'science', which at the same time was hardly differentiated from astronomy. Furthermore, from the 4th century onwards, the Christian-Roman Empire increasingly determined which knowledge could still be considered permissible. Astrology was declared a 'mistake' under Emperor Valens (4th century), and at the beginning of the 5th century by Honorius and Theodosius, it was finally declared a heresy against the Catholic faith. And it was only with the latter that astrology was finally separated from the traditional scientific context and devalued as an ordinary deviation from belief. At the same time, at councils such as that of Laodicea in 365 or Braga in 572, all astrological activity was forbidden for church members. Thus, after Christianity was elevated to the status of the state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, astrology increasingly disappeared from the 'academic' world and learned perception as well as the public. But then of course astrology itself did not disappear, and a. because apart from the capital cities there were greater freedoms and at the same time the complex of astrological knowledge was transformed into Christian views.

There were some starting points for the latter development:

- The numbers 4, 7 and 12, which played a major role in early Christianity , are reminiscent of the language used in ancient astrology, although their prognostics are not adopted;

- in Mt 2 EU there is a report of the “magicians” or wise men from the east who looked for the newly born King of the Jews in Jerusalem, because they had seen “his star”, the star of Bethlehem , rise; from this the tradition of the Magi developed ;

- the crucifixion of Jesus is accompanied by a solar eclipse between the sixth and ninth hours in the Gospels of Matthew , Mark and Luke ; likewise the end times before the second coming of Jesus z. B. in Mt 24.29 EU , and Acts 2.20 EU and Mk 13.24 EU ; Lk 21.25 EU speaks of signs on the sun and moon as well as stars;

- in the Book of Revelation For Christ are: the elements of an end-time stamped astral mysticism and astrological allusions are more evident Rev. 1.4 to 20 EU seven stars added, either as the seven "planets" of ancient astrology or as the Pleiades are interpreted can; the four beings, which are named according to Rev 4, 6-8 EU based on the description of the Merkaba in Ezekiel , can be interpreted as correspondences of the four corner points of the zodiac.

As a result of the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, astrology as a practiced and learned tradition largely dried up in its territories, although astrology was far less anchored and widespread there anyway, since its development and spread ultimately in the Near and Middle East and the originated in the eastern Mediterranean. In addition, with a few exceptions, the astrological literature was written and handed down in Greek, the most important language in the Eastern Mediterranean and Eastern Current, while Latin had largely dominated in the Western Roman region. In the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium , astrology was retained, albeit weakened and also in the later, but from the 7th / 8th century. Byzantine history, traditionally attributed to the Middle Ages.

From the time until the reign of the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I, which was increasingly seen as Christian, in the 6th century, as before, many birth and catarch horoscopes have survived. B. worked for the Eastern Roman Emperor Zenon (Emperor) (5th century). However, in the 5th century in Beirut , Eastern Roman territory, astrology books were publicly burned and in the 6th century under Justinian I the teaching of the Neoplatonic philosophy school in Athens was stopped, which is said to have affected astronomy and astrology teachers as well. The last significant and tangible late antique representative of Hellenistic or classical astrology, Rhetorius of Egypt , also appropriately belongs to this Eastern Roman phase of the history of astrology. He probably worked around 500 or 600 AD and is said to have been Egyptian, parts of his very sophisticated astrology texts with references to z. B. Vettius Valens have been handed down indirectly. At the transition from late antiquity to the Byzantine Middle Ages, the recognized philosopher, teacher and astronomer-astrologer Stephanos of Alexandria can be identified, who was apparently brought from Alexandria to Constantinople by the Byzantine emperor Herakleios himself, reign 610 - 641, in a late phase of the cultural revival .

The complex or parts of the Hellenistic or classical astrology itself were probably already from the 2nd century AD. B. mediated to India and from the 3rd century admitted to the Greater Persian Sassanid Empire . For example, the astrological treatises of Dorotheus of Sidon and Vettius Valens were translated into Middle Persian of the Sassanid Empire. After the conquest of the Sassanid Empire in the 7th century, the new Muslim-Arab empire, in turn, evidently received or translated the astrological ideas of Hellenistic, Persian and Indian origins found there. The first known and important teacher of astrology, astronomer and translator from Greek in the Arab Empire is the Syrian Greek and Christian Theophilos von Edessa .

middle Ages

In the medieval period of astrology between antiquity and late antiquity, with its classical, Hellenistic astrology, and the modern era , the question horoscopes and 'elections' - the choice of an astrologically favorable point in time for a project - dominated by far in astrological practice and teaching the so-called hourly astrology and oral astrological topics , including z. For example, questions about the development of weather and agriculture were included, etc. A very important reason for this astrology focus was that many clients had neither reliable knowledge nor reliable evidence of their date of birth, and certainly no exact time of birth, just as often was the geographical one Position of the place of birth often unknown. But only under these conditions was and is the creation of a natal chart with the following interpretations.

Furthermore, most of the clients or visitors of an astrologer had specific questions about current problems or life situations and little interest in the comprehensive interpretation of their own life path using the natal chart.

With the three monotheistic religions Judaism , Christianity and Islam there were typical, widespread points of conflict with the philosophical and religious implications that were carried along by the complex of astrology:

- the subject of human free will

- the theme of the divine worship of the stars

- the topic of the independent, God-independent effectiveness of the stars

- the subject of predestination through a deterministically understood astrology

- the topic of non-divine forecasting possibilities through astrological methods

Islam

In the Middle Ages , astrology from late antiquity continued to be cultivated, especially in the Islamic cultural area, with the reception of Hellenistic astrology as well as Indian and Persian-Sassanid astrology elements. As specifically Indian and Sassanid astrology developments or inventions, which were adopted by the subjugated Sassanid empire in the Arab-Islamic astrology, include u. a. the so-called 'military' astrology as well as the basics of hourly astrology, as well as astrological considerations of history based on u. a. of interpretations of the annual Aries -Ingress the sun and the Great Conjunction , the Saturn - Jupiter - conjunctions and with their cycles. Another Sassanid invention was the astrologically planned moment of rulers' coronations with a suitable horoscope, as it was handed down for the Sassanid great king Chosrau I , reign 531-579 AD.

From the 8th to 10th centuries, astrological texts were collected and translated in the Arab world. The Baghdad Library was a prominent center of these activities . Therefore, at that time, a large part of the astrological works of Hellenism such as Valens Anthologiae were available in Arabic translation. At the same time, some technical facilitations of the work of astrologers were developed.

Typical for the beginnings of astrology in the Arab-Islamic empire was z. B. The activity of Theophilos of Edessa in the 8th century. The Greek-speaking, Christian- Maronite Syrian translated many Hellenistic astrology texts into Arabic, e. B. Valens' Anthologiae , and later worked as an astronomer and astrologer - astronomers - at the court of the caliphs al-Mahdi and al-Mansur in Baghdad. Theophilos, whose works are said to have been housed in the secret library of the caliph's court in Damascus, had u. a. probably a preference for 'war astrology', i.e. for the astrological assessment and interpretation of acts of war. The Indian astrologer Kankah , also written Kanakah or possibly Katakah and biographically hardly comprehensible, even if u. a. named by Abu Ma'schar , as well as the astrologer and astronomer Messahallah , who converted from Judaism to Islam , who both advised and taught at the court of the caliph in Baghdad, complete the picture of the early Islamic-Arabic astrology phase.

Since the Koran condemns the worship of astral deities, but accepts the interpretation of heavenly signs to understand the will of Allah , Muslim rulers have always supported the development of astrology as well as other sciences.

Various Islamic scholars and writers, such as the linguist al-Chalīl ibn Ahmad al-Farāhīdī , testified from the 9th century, directly and indirectly, their rejection of astrology itself. Written works on the theological refutation of astrology are available for the first time from around the end of the 10th century. B. in ʿAbd al-Jabbār ibn Ahmad or al-Bāqillānī , they mostly postulated the incompatibility of an astrologically often assumed, autonomous activity of the stars with the sole activity of God, the first and only cause, formulated in the Koran . Criticism of astrology (such as Avicenna in the 11th century ) and philosophical refutations, e.g. B. from al-Fārābī , are visible a little earlier, probably for the first time in the first half of the 10th century.

With al-Fārābī (9th / 10th centuries), who had rejected astrology himself and later involuntarily contributed to its greater acceptance in Western Europe, a largely divided assessment of astrology can be recorded for the Middle Ages. He considered it, in his treatise Iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm ('Book of the Classification of Sciences'), together with astronomy as part of the mathematical science. Related practices and worldviews such as astral magic or magical astrology, which was not only widespread in the Middle Ages. For him, making talismans , for example , was not part of mathematics, which was probably also a mediaeval consensus. In Al-Fārābī's understanding of science, however, astral magic and medicine did not appear at all. Less than a century later, the Persian scholar al-Ghazālī (11th / 12th century) in his work Maqāṣid al-falāsifa ('The intentions of the philosophers') et al. a. magic and medicine were seen as part of what was then often understood as natural science, astrology continued to be part of mathematics. The writing of al-Fārābī on the classification of the sciences as well as the treatise by al-Ghazālī later became known and widely received in Christian-Latin, Western Europe through translations in Toledo of the 12th century, regardless of whether one came from, for example, religious , ethical or philosophical reasons the astrology or the astral magic - partly - rejected. The eminent scholar and translator Dominicus Gundisalvi in Toledo in the 12th century again classified astrology as an outstanding 'science of judgment' on the basis of the 'classification of the sciences' by al-Fārābī, which he quotes in detail, and other Arab scholars has been widely accepted and has made astrology more widely accepted. With Gundisalvis, the distinction between astrology , which goes back to Isidore of Seville (7th century) and is decisive in Latin-Christian, western Europe, into a so-called "natural", acceptable astrology (such as astrology, astrological medicine , astrological considerations of history) and a " Judicial ”, “ superstitious ” and dismissible astrology (such as prognoses on natal charts, question horoscopes and“ elections ”) expanded or overcome.

Overall, astrology and astrologers remained fairly loyal companions until the 20th century, above all to countless Muslim rulers, regional princes such as grand viziers and their courts, including in the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Mahmud II. Astrology was often tolerated, even though it was under religious law was clearly rejected. However, astrologers and astrology in general had gone through an Islamization, so to speak, in the course of time. B. in the form of astronomy that is increasingly geared to Islamic-religious needs and pushed to the fore. In this cladding, the genuinely astrological content and interpretations could survive, probably similar to the process of Christianization of astrology in late Roman antiquity.

As Islamic culture spread from Spain to China, Muslim scholars combined the Hellenistic and Babylonian traditions of astrology with corresponding Indian and Chinese teachings.

The Arabic-Islamic astrology experienced a heyday in the Orient until the 11th century, after which it was strongly connected with esoteric-occult ideas and practices, a process that perhaps contributed to the beginning, slow decline of the 'scientific' astrology taught there . Finally, with the conquest of Baghdad (1258) and the Arab-Islamic caliphate by the Mongols a. a. the broad teaching and practice of 'scientific' and court astrology often come to a standstill. Already at the beginning of the astrological heyday in the Islamic-Arabic Orient from the 8th century, the Arabic-Islamic astrology, together with the Hellenistic or classical astrology works of late antiquity it received, were passed on to the competing Byzantine Empire and Constantinople , for example . So apparently by Stephanos Philosophos (8th century) in the context of increased intellectual interest u. a. on astronomy in Byzantium in the run-up to the so-called Macedonian Renaissance . Stephanos, who had moved to Constantinople from Islamic Persia , maintained the high scientific rank of astrology and noted that the stars should of course not be worshiped as divine within the framework of Christianity and that they should not be subject to any autonomy of will. The works of Theophilos von Edessa, the scholar and astrologer at the Islamic caliphate in Baghdad, who had also written about the harmonization of Christianity and astrology, were also widely received in Byzantium from the 9th century onwards in the cultural boom of the Macedonian Renaissance the astrological treatises of other scholars and astronomers-astrologers from the Islamic-Arab Orient such as Abu Ma'schar and Sahl ibn Bischr, which were translated into Greek for this purpose. The cultural relations between Constantinople and the expanding Arab-Islamic empire apart from the armed conflicts are also made clear by the fact that Caliph al-Ma'mūn (first half of the 9th century) wanted to bring the outstanding scholar Leon, the mathematician, from Constantinople to Baghdad, and a. apparently especially because of Leon's skills in mathematics and geometry, and probably also because of his astrological scholarship.

But especially during the Arab-Islamic rule on the Iberian Peninsula (8th century to 15th century), called Al-Andalus , and the beginning of the Christian reconquest , some a. numerous astrology texts z. B. in Toledo through translations from the 12th century gradually received from southern Europe in high medieval Christian Europe, which led to the first European heyday of astrology from the 13th century. Jewish scholars also played an important part in this translation activity and dissemination of astrological works such as knowledge of and from Islamic Spain. The most influential work of Jewish astrology of that time was the Sepher reshît hokhmah (12th century) by Abraham ibn Ezra .

The emerging, later Ottoman Empire , in turn, largely took up the Arab-Islamic astrological astronomy that was handed down there from the time and dominion of the Seljuks . At times the Seljuks in the 11th and 12th centuries had B. ruled over the astrology stronghold Baghdad, from the Seljuk sultans Tughrul Beg and Alp Arslan their great interest in astronomy and astrology is passed down. According to a historian at his court, Alp Arslan is said to have consulted astrologers about their prospects and appropriate times for the battle at Manzikert . As is customary in the Islamic Orient, there were also official court astronomers, i.e. astrologers-astronomers, at the Seljuk rulers' courts.

In the Ottoman Empire with the new capital Istanbul , the institution of munajjim-bashi , the official court astronomer, the 'chief astronomer-astrologer', developed rapidly between the late 15th century and the early 16th century at the Sultan's court in Istanbul, to which several assistants were subordinate. It remained in place for centuries until the end of the Sultanate in Istanbul, until the early 1920s. Some typical fields of activity of astronomer-astrologers at the numerous other, earlier Islamic rulers' courts can probably be derived from the official duties of the chief astronomical expert at the Sultan's court in Istanbul:

- Creation of public annual calendars or almanacs , etc. a. With historical chronologies, the oral astrological horoscope for the Aries ingress of the spring equinox including interpretations, predictions about the weather, sultan and government, astrological evaluations of the days of each month for suitable and unsuitable activities ('elections'), solar and lunar eclipses throughout the year astrological interpretations;

- Creation of the Ramadan calendar;

- Calculation of astrologically suitable times - elections - for public and private acts and activities of the Sultan and members of the government, state and government activities;

- Information from the palace about eclipses, comets and other earth and sky phenomena;

- Organization of the exact timing, for example for the exact times of prayer, and the muvakkithane (' Zeitgeberhaus ') with the staff there, the muvakkits ;

The most important astrologers of the Islamic Middle Ages were probably al-Kindī and his contemporary as well as colleague and likely student Abu Ma'shar , both from the medieval, Arab-Islamic Orient and teaching in Baghdad. On the basis of the stoic concept of an all-unifying sympathy, Al-Kindī developed a holistic view of the cosmos, in which heavenly and earthly bodies, but also words and actions, influence each other by emitting rays. Abu-Ma'shar viewed astrology as a mathematical science. In his influential Introductorium in Astronomia (Latin translation) he gave an overview of all classical astrological techniques including those of the Indians. In Zìj al-hazaràt he spoke of the fact that astrology was originally given to people through divine revelation, but has now largely been forgotten. Subsequently, he developed a philosophical foundation for astrology, which was supposedly based on a very old script, which had been hidden for a long time and whose content he is now making accessible again. Also important were Abu-Ma'schar's explanations about the triple grand conjunction , the rare event that from a geocentric point of view, Jupiter and Saturn touch each other three times in a row within a year. This constellation has long been ascribed a special meaning, but Abu Ma'schar now applied this to the question of when the Mahdi , the equivalent of the Messiah in the Shia , would return. This was the model for corresponding speculations in Jewish and Christian culture up to modern times.

Services of Arabic astrology :

- improved, more precise planetary tables - the ephemeris for calculating the planetary and fixed star positions - due to further developed astronomy and mathematics;

- Further development of the so-called catarch astrology to the hour astrology still used today ;

- oral astrological consideration of history, especially with the interpretation of Saturn and Jupiter conjunctions or cycles, the so-called grand conjunction , a method which is of Sassanid-Persian origin;

- Oral astrological interpretation of the so-called Aries ingress , a horoscope for the moment in which the moving sun reaches the zodiac sign Aries;

- Return horoscope or solar horoscope for the exact time of the return of the sun to the exact position of the birth sun; only the Arab natal astrology developed horoscopes for this moment, before that were interpreted in the solar return only the Zodiac positions of the moving planets to natal chart;

- Increase and further development of the so-called sensitive points, the best known is the luck point;

- Use and interpretation of the so-called moon houses from Indian origin

Christianity

Byzantine Empire

The culture and the spiritual life of the Byzantine Empire can be regarded as the immediate Christian heir of late antique, Hellenistic astrology in the medieval Christian area even before Latin-Christian Europe. And the majority of the Greek-language astrological manuscripts published in the authoritative Catalogus Codicum Astrologorum Graecorum come from the Byzantine Empire. These Byzantine astrology manuscripts have so far only been rarely evaluated and edited, so that the picture of astrology in Byzantium is likely to be rather incomplete. However, the previous publications and works are gradually making the importance and scope of astrology there more visible.

Around the beginning of the Byzantine Middle Ages stands the philosopher, teacher and astronomer-astrologer Stephanos of Alexandria , whom Emperor Herakleios himself, reign 610 - 641, apparently brought from Alexandria to Constantinople at a time of cultural revival.

With the astrological heyday in the neighboring Islamic-Arabian Orient, the astrology there, including the Hellenistic or classical astrology works received, was widely received in the competing Byzantine Empire. A Stephanos Philosophos (8th century), for example, apparently acted as mediator and stimulator in the context of a growing interest in astronomy in Byzantium . Stephanos, who moved to Constantinople from Islamic Persia , spoke a. a. of the high scientific rank of astrology and demanded that in Christianity the stars were of course not entitled to any divine veneration, nor should they be subject to any autonomy of will. And the works of Theophilos von Edessa , the scholar and astrologer at the Islamic caliphate in Baghdad, who also tried to harmonize Christianity and astrology, were widely received in Byzantium from the 9th century. This also applies to the astrological texts of Islamic scholars and astronomer-astrologers such as Abu Ma'schar and Sahl ibn Bischr. The cultural-spiritual exchange between Constantinople and the expanding Arab-Islamic empire is also evident from the fact that Kalif al-Ma'mūn ( first half of the 9th century) Leon the mathematician wanted to bring from Constantinople to Baghdad, probably also because of his astrological scholarship. In the 11th / 12th In the 18th century, there was apparently a varied transfer between the Egyptian Fatimid Empire and the Byzantium of the Comnen dynasty, also on astrological level. At that time Egyptian astrologers were apparently working in Constantinople, probably also for the imperial court there, while the so-called Great Hakimitic Tables ('al-Zij al-Kabir al-Hakimi') by Cairo astronomer Ibn Yunus , the ephemeris for astronomical such as Astrological calculations that were used in Byzantium.

During Byzantine history, interest in astrology-astronomy and its practice fluctuated considerably, as elsewhere and in other epochs. Around the end of the 8th century, after many decades of military conflicts, first with the Sassanid Empire, then with the expanding Arab-Islamic Empire, their attention rose sharply. Practice and teaching reached a high point during the Macedonian Renaissance in the 9th / 10th centuries. Century. So are u. a. for Emperor Constantine VII (10th century) natal charts including a detailed interpretation. . In the 11th and 12th centuries was again an upswing during the Komnenen - dynasty instead. Horoscopes for the moment of coronation have been created for both Alexios I Komnenos and his Manuel I Komnenos - in Sassanid tradition - Manuel I even has a treatise on the defense of a Christian astrology. Anna Komnena , the historian and daughter of Alexios I. Komnenos, explains in her well-known historical work Alexiade (written around 1148) the new nature of the natal chart in relation to the capabilities of the ancient models such as Plato or Eudoxus of Knidos , the 'ancients' in Connection with a spectacular forecast of the late 11th century.

For the Byzantine Palaiologos dynasty (13th -. 15th century), another golden age of astrology are detected, at which even the imperial court had been mitbeteiligt in Constantinople Opel. For example, a proclamation horoscope (1373) has been handed down, this time from Manuel II. Palaiologos , but only for his office as co-emperor of Johannes V. Palaiologos In the late 14th century there are now two scholars and astronomer-astrologers, Johannes Abramios and Eleutherios von Elis , in a group of other students and astrologers, probably u. also working in Constantinople, tangible through various, sometimes more extensive, manuscripts.

As in Christian late antiquity and in medieval Islam, astrologers were expelled from Constantinople, astrological activity was temporarily banned and astrology was criticized and discredited, especially by church people and theologians. Regardless of this, centuries before a learned astrology was used in Latin-Christian, Western Europe in the Byzantine Empire, sophisticated, learned techniques and methods such as natal chart, hourly astrology or so-called military astrology were often used, methods that were always academic 'Required knowledge of mathematics and astronomy. In addition, in some cases, techniques which late ancient Hellenistic astrology were not yet familiar with and which Byzantium had only received as a further development from the Islamic-Arabic Orient. Whether independent astrological techniques or areas of astrology were developed in the Byzantine Empire has not yet been a subject of scientific research, as far as can be seen.

On the other hand, it is clear that learned followers of humanism, which first emerged in Italy from the late 14th century onwards as part of the European Renaissance, used Greek-language manuscripts to a large extent, actually or supposedly ancient works in Byzantium of the Palaiologian dynasty or in earlier areas of the Byzantine Empire or had them copied. The discovery of Greek texts from the Corpus Hermeticum in Macedonia in 1463, which was believed at the time to transmit the oldest wisdom teachings of mankind , also belongs in this context, which was extremely important for the emerging esotericism such as occultism and hermetics of the Renaissance . Above all, the legendary Hermes Trismegistus , who gave it its name , was astrologically equated with Mercury . As a result of the translation and publication of the corpus texts, many poets and astrologers of the Renaissance identified with Mercury, and astrology was subsequently taught and considered more often as part of hermetics. At the same time various Byzantine scholars worked in Italy such as Bessarion and Georgios Gemistos Plethon , especially in Florence. Numerous astronomical-astrological treatises from the Byzantine period came as manuscripts and the like. a. to Italy, like those around Johannes Abramios. Because of the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, more Byzantine scholars left their homeland for Italy and more western Europe. It can be assumed that the transfer of these manuscripts, as well as the work of Byzantine scholars in Italy and Latin-Christian Europe, were able to make an independent contribution to or further boost the development of astrology in the Renaissance. Impact work on this is apparently not yet available.

Latin-Christian Europe

The transmission of simple forms of astrology took place in the early Middle Ages of Latin-Christian, Western Europe, especially in some monasteries, in which the astrology writings that were still in Latin, such as those collected in particular by Boethius and Isidore of Seville , were passed on. Those simple, lay astrological forms from the complex of astrology, such as simple interpretations of the signs of the zodiac, especially as part of an adaptation to Christian teachings, shaped the initially few and mostly timid applications of astrological origin well into the High Middle Ages .

Natural astrology and Judiciar astrology : In his Encyclopedia Etymologiae, Isidore made a centuries-old distinction between a natural and a superstitious astrology. He described the endeavors of astrology to want to determine the character and fate of a person from the natal chart as superstitious. He did not deny that one could possibly come to knowledge in this way, but since the victory of Christ it was pointless and therefore no longer permissible. The natural astrology permissible according to Isidore dealt with weather forecasting or medical questions, in the latter respect he recommended that every doctor should have an astrological training. With Isidore, as was often the case in the later centuries from the Middle Ages to modern times, there is no clear distinction between astronomy and natural astrology.

The superstitious astrology rejected by Isidore thus largely only affected the natal chart prognoses. A field of astrology that will later be referred to as Judiciar Astrology or 'Astrologia judiciaria' in the Middle Ages as well as in modern times, as 'Judging' astrology. From the High Middle Ages , when the increasing knowledge of "scientific" astrology in Latin-Christian Europe made it possible, for example, to calculate horoscopes and forecast the future, it was the focus of both theological-Christian and philosophical criticism and prohibition measures. In the 12th century the scholastics Petrus Abelardus and Hugo von St. Viktor taught accordingly that astrology could make statements in the area of natural causes, but not about contingentia that depend on chance and the will of God . These assessments would become the official stand of the Church for centuries. The papal prohibitions and decrees (' bulls ') of the 16th century, for example against divination and magic as well as astrology, largely concerned only divinatory prognostic techniques including concrete future predictions for natal charts, as opposed to permitted, natural astrology. The well-known bull of Pope Sixtus V. Contra exercentes artem astrologiae iudiciariae et alia quaecumque divinationum genera, librosque legentes vel tenentes turned against judicial astrology based on divination and concluded from the ban, however, 'real scientific' forecasts based on 'natural causes' and' statistical frequencies'. Long before the Bull of Sixtus V, and even more so afterwards, learned astrologers and astrologers had often emphasized that the astrological prognoses were based on the assumption that the heavenly bodies exerted a physical influence on earth and man, and thus in turn on collective events such as individual fates. With this argument one tried to connect to the natural and allowed astrology, which according to the understanding of 'physics' like cosmology at that time had 'natural causes' as its origin. In somewhat older Catholic theological lexicons, astrology was still divided and defined into these two areas. A substantive differentiation between natural astrology and astronomy was still not given until the 17th century.

In the 1260s, the scholastic Albertus Magnus may have written the Speculum Astronomiae , but this is not certain, as the effect of this writing apparently remained rather small. In the work, a distinction is made between magical use and scientific testing, and at the same time the distinction between astronomy and astrology is introduced as two branches of one science. Astronomy is viewed as a mathematical discipline, the calculations of which are interpreted by astrology and used to make statements about future events. Astrology leads all earthly things back to their divine source and therefore also leads people to God. Thomas Aquinas argued that astrology is based on reason and that this determines the will. On the other hand, Averroists like Johannes Duns Scotus objected that the will stands above reason and that therefore God's will cannot be grasped by reason. Roger Bacon , who viewed astrology, alchemy and magic as empirical sciences, went even further than the author of the Speculum Astronomiae . In doing so he referred u. a. on Ptolemy and Abu Ma'shar, claiming that no serious astrologer has ever taken a fatalistic or deterministic position. Also in the second half of the 13th century a detailed criticism of astrology by the Dominican Gerhard von Sileto (Gerhard von Feltre) Summa de astris appeared .

Astrological prognoses and interpretations, applications such as methods based on a learned, 'scientific' astrology in connection with the necessary mathematical-astronomical knowledge are only tangible from the 12th century in Latin-Christian Europe. This happened mainly as a result of the Arab-Islamic rule on the Iberian Peninsula (8th century to 15th century) and the beginning of the Christian reconquest . In this context, u. a. numerous astrology texts z. In Toledo, for example, it was gradually received in high medieval Christian Europe through translations from the 12th century onwards, with the first astrology blossoming in the 13th century.

For the Sicilian court of the Norman King Wilhelm II of Sicily (2nd half of the 12th century), what is probably the earliest tradition of learned, practiced astrology for Latin Europe is certain (1183/1184). Made by Islamic astronomers / astrologers, as the Islamic geographer and travel writer Ibn Jubair reported from Spain . Before the Norman control, Sicily could look back on a longer phase of Islamic-Arab rule, starting not from Al-Andalus / Spain, but from emirs from Tunisian territory , so that the well-known Arab-Islamic scholars at the court of the Norman King Roger II. of Sicily , grandfather of William II of Sicily, apparently did not come from Spain. Another grandson of Roger II of Sicily, the Hohenstaufen king and heir to the Norman rule Friedrich II (1194–1250), continued the Norman court tradition and with it the use and promotion of learned astrology / astronomy in Sicily. The scholars such as Michael Scotus or Theodor of Antioch who were temporarily involved in it, however, worked in several areas and functions at the court. Scotus had previously translated numerous Arabic-language works in Toledo , including a. Astrological / astronomical, Theodore, for example, was trained by Arab scholars in Mosul and Baghdad.

It was the hourly astrology from the field of astronomy / astrology that was most frequently practiced and used in addition to the 'natural' astrology / astronomy, which was self-evident for the entire Middle Ages, otherwise the focus was still on oral astrology . For reasons already mentioned, the interpretation of natal charts was rather rare or hardly possible in the High Middle Ages.

Similar to the court of Frederick II, a generation later the Castilian court under Alfonso of Castile (1221–1284), who was related to the Hohenstaufen, promoted a great deal of scholarship in his place of birth, Toledo, as part of a translation school he had recently initiated. Arabic works of astronomy / astrology were also transmitted and disseminated in particular. The well-known Alfonsin Tables , ephemeris with the daily position values of the planets, are also a result of this funding. In contrast, nothing concrete is known of Alfons' court about astrological advisory activities.

From the first half of the 13th century, the learned astrology in Latin Europe gradually spread from the south to the numerous larger cities that were emerging, in northern Italy perhaps even from Sicily, where Guido Bonatti is probably the best known and in many cases still far in Forli later quoted astrologer / astronomer of the 13th century had practiced. The founding of universities in the course of that century, such as in Paris or Bologna and subsequently in all of Latin Europe, probably also promoted this development, as the seven liberal arts , which go back to antiquity, were taught at the universities as a 'preliminary course' . These included a. the mathematical subjects arithmetic (number theory) and geometry (including geography and natural history), music (music theory) and astronomy (then including the methodological and astronomical basics of astrology).

The Latin-European late Middle Ages with a growing population, increasing economic output and further founding of universities and urban high schools increased the demand and spread as well as independent further development of astronomy / astrology. Astrology experienced a further, noticeable impetus in the transition from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period from the Renaissance humanism , which initially developed particularly in Italy from the late 14th century and led to the European renaissance of the early modern period. Typically, along with this development, the individual and a more antiquated, pantheistic worldview moved more into the center, so that the creation and interpretation of natal charts became more and more important and finally increased significantly. The invention of the printing press in the late 15th century accelerated the spread and accumulation as well as the improvement of astrological works and textbooks such as ephemeris.

Modern times

Early modern age

In Renaissance humanism and in the Renaissance , learned astrology experienced a further heyday, which lasted until the late 17th century. It was mainly cultivated at courts and at European universities. At the universities, for example, it was taught together with astronomy at the artist faculties , but also at the medical faculties, since at that time medical treatments and operations iastroastrologically were often based on the positions of the planets and the moon, and in connection with Aristotle's natural philosophy, on the other hand, it was also possible at that time Be part of a theology course. The focus of the astrology taught and practiced was initially in Italy. Many popes of that time also promoted astrology, including Pius II , Sixtus IV , Leo X and Paul III. From Italy it then spread across Europe. The Habsburgs were important sponsors in German-speaking countries .

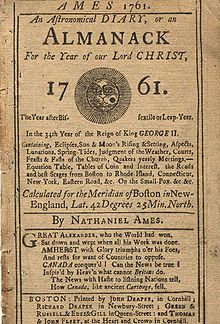

With the advent of the printing press , the production of numerous popular astrological publications such as forecasts, annual forecasts, almanacs and representations of astrological medicine began. Predictions based on the Great Conjunction of 1484 attracted particular attention. This was interpreted mundanastrologically as the announcement of a false prophet and a new holy religion, the latter leading to new laws that would restrict the privileges of the nobility and help the poor. This was later referred to by Protestants and Catholics in opposite ways to Martin Luther . The major conjunctions were subsequently also used to predictively date events that were foretold in the Bible. However, the Catholic Church turned against such practices and put astrological writings on the index, whereas astrology was free to develop in Protestant areas, although Luther had been critical of it and John Calvin rejected it.

Announced today the forecasts for the conjunction of six planets are Zodiac sign Pisces in February 1524 numerous astrologers said mundanastrologisch for this period a great flood before, but failed to. Instead, the German Peasants' War broke out in June of the same year , which was subsequently interpreted as a result of the planetary agglomeration in the fish.

The development of Renaissance astrology was due to the fact that ancient writings that had been unknown in the Middle Ages were found again and that Arabic and medieval writings were distributed in printed form. Of particular importance, however, was the translation of Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos and the pseudo-Ptolemaic Centiloquium from the Greek originals into Latin in the middle of the 16th century. These translations formed the basis of a reformist current in astrology, of which Gerolamo Cardano was the most important representative and which spread throughout Europe. They wanted to free ancient astrology, of which Ptolemy was seen as the most important exponent, of Arabic “superstition” and the lure of magic. The "Ptolemies" also rejected technical innovations developed in the Arab world.

The so-called astronomical revolution, the transition from the geocentric view of the world to the heliocentric view of the universe, did not affect astrology. Astrologers continued to adopt the geocentric or anthropocentric perspective, which is not tied to the geocentric or heliocentric worldview, and many of the protagonists of the new astronomy, including Nicolaus Copernicus and Tycho Brahe , Johannes Kepler or Galileo Galilei, also pursued or were astrological studies astrologically advisory. For the first time in the history of astronomy, Kepler's planetary orbit calculations enabled exact details of the planetary positions in the ephemeris, which astrology also needed, after the Copernican model of the - inaccurate - circular planetary orbits in its heliocentric cosmos model did not improve the accuracy of the ephemeris compared to the Alfonsine tables Had led.

The Ptolemaic direction, which was linked to the Aristotelian natural philosophy , was opposed to a Platonic and hermetic interpretation of astrology, as represented by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim , Paracelsus and Robert Fludd . With the help of astrology, Agrippa tried to penetrate the web of analogies which he believes connect the elemental, the heavenly and the divine worlds. A third direction was represented by Kepler, who heavily criticized Fludd in particular, but also took up Plato's view of the cosmos as a perfectly ordered whole in which everything is created according to harmonious geometric proportions. On this basis he developed a theory of the aspects between the planets corresponding to the melodious and discordant chords in music.

For a long time the papacy was interested in astrology. Sixtus IV. And Alexander VI. is held court astrologers , Julius II. and Paul III. put important dates on supposedly favorable days. The Florentine preacher Girolamo Savonarola was burned in public not least because of his angry agitation against astrology . This astrology-friendly attitude of the church changed in the course of the 16th century until the Council of Trent in 1563 passed a ban on astrology, which was renewed in the course of the Gregorian calendar reform in 1582.

When, towards the end of the 17th century, natural philosophy increasingly turned to a mechanistic view of the universe, the philosophical foundations of astrology lost their plausibility. This led to the decline of learned astrology, which was soon no longer represented in universities, and also resulted in increased bans on the practice of astrology.

In the Age of Enlightenment , educated circles distanced themselves even more clearly from astrology. It was considered a “ superstition ” and “ after science ” and was increasingly the subject of ridicule: The Irish satirist Jonathan Swift made fun of his contemporaries ' faith in predictions by publishing an astrological almanac for 1708 under the pseudonym Isaac Bickerstaff therein predicted the death of the astrologer John Partridge . In 1709 a pamphlet followed with the claim that this prediction had come true, which was generally believed: Partridge had some difficulties in convincing his fellow men of his continued life. In their Encyclopédie , Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert and Denis Diderot described astrology as unworthy of consideration by sane people, and Voltaire subscribed to this view. At that time, studies of astrology were largely limited to secret societies , where in the 18th century a revival of hermetic astrology in connection with Neoplatonic and Gnostic elements took place.

Modern

In the 19th century, especially in England, astrological studies flourished again, which were based on the Ptolemaic direction and mainly dealt with technical aspects and empirical tests. In France, however, astrology was not practiced again until the late 19th century, mainly in secret societies. This esoteric astrology was popularized mainly by Eliphas Lévi and Papus . At the same time, an esoteric variety of astrology developed in the English-speaking area around the Theosophical Society founded in 1875 , the most important representatives of which were Sepharial and Alan Leo . Leo's textbooks did a lot to popularize astrology.

In Germany, Karl Brandler-Pracht in particular caused a resurgence of astrology from around 1905. In the following decades, various new approaches were developed there, including a. the half-sum astrology by Alfred Witte and Reinhold Ebertin .

The most famous astrologer of the early 20th century was Evangeline Adams . She settled in New York in 1900 and advised many people as an astrologer, including millionaires such as JP Morgan , the singer Enrico Caruso or the British King Edward VII. In 1914 she was charged with divination, but acquitted.

In his book Astrology as empirical science , published in 1926 , Herbert von Klöckler presented a statistical study of correlations between astrological factors and events such as accidents, murders, suicides and divorces. The supporters of such a “scientific” astrology included the biologist Hans Driesch and the paleontologist Edgar Dacqué .

In the first decades of the 20th century astrology was predominantly event-oriented. In so far as it dealt with the character of people, this was mostly done on the basis of very simple ideas of personality. In the 1920s, astrology titles with a strong psychological orientation in interpretation were published for the first time in German-speaking countries, and they may even have been the earliest psychologically influenced astrology works. The first tangible book of this direction came from Oscar AH Schmitz , published in 1922 under the title The Spirit of Astrology , which had already been shaped by the analytical psychology of Carl Gustav Jung . A few years later Herbert Freiherr von Klöckler became known as an astrologer and author of psychological horoscope interpretations. In the English section was followed by a first turn to newer psychology by Dane Rudhyar with his book The Astrology of Personality (1936), in which he astrology with psychology (Carl Gustav Jung) and theosophy ( Alice Bailey Association).

Even before the National Socialist seizure of power at the beginning of 1933, astrologers with ideological proximity to National Socialist ideas were influential in Germany's astrology scene. They included, for example, Rudolf von Sebottendorf , the founder of the short-lived Thule Society , 1920 editor of the Astrological Rundschau and author of a history of astrology published in 1923 , which was based on the racist phantasmata of the Ariosophers and Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels and Guido von List . The enthusiastic Hitler supporter Elsbeth Ebertin published a horoscope for the " Führer " in July 1923 , which was seen as a prophecy of the Hitler putsch . During the Nazi era , almost all astrological papers in Germany gradually published racist texts about the supposedly “Nordic” astrology, and some German astrologers began to write about the “ Tyrkreis ” instead of the zodiac . After the astrologers' associations had been cleaned up in the spirit of the National Socialists , more calm returned. Astrological activities and publications were tolerated to a certain extent; in September 1936, an international astrological congress with 400 participants was even held in Düsseldorf. Since then, however, restrictions and bans have increased, and by 1938 the astrology scene had already largely been smashed or gone underground. After Hitler's deputy Rudolf Hess' flight to England in May 1941, all astrological magazines were banned, all associations were dissolved, and leading astrologers were sent to the concentration camp . Hess, a believer in esotericism, had held his protective hand over astrology, but Hitler is now said to have declared that his flight to England seemed to him “to be largely due to the astrological clique that Hess had around him. It is therefore time to radically clear up this magical nonsense ”. Hess' opponents in the polycratic ruling apparatus of the National Socialists now started the action against secret doctrines and so-called secret sciences , which had already been prepared before the flight to England. From then on, astrology was considered a “Jewish” invention in the Nazi state and it was spread that the word rascal came etymologically from astrologer .

Astrology, which is based on psychology, is skeptical or even negative about prognoses and places particular emphasis on freedom of will and human development, while the individual is partly bound by his astrological disposition, talents and weaknesses. Most of the representatives of this direction refer to Jung's depth psychology , in which the synchronicity principle plays an important role. Events in the life of an individual can "accidentally" coincide with constellations of the stars in such a way that meaningful statements result from the symbolic interpretation. With this, astrology has broken away from the idea of a causal influence of astronomical factors on humans. Hans Driesch spoke of astrology as a doctrine of "acausal correlations".

Western astrology has been booming since the late 1960s. A major trigger was the concept of the Aquarian Age , as it became known through the musical Hair . Since the fall of the Iron Curtain , it has also increasingly found supporters in the former Eastern Bloc , and in the course of globalization it spreads worldwide.

literature

- Nicholas Campion: A History of Western Astrology. 2 vols., Continuum, London / New York 2008, 2009.

- Jürgen Hamel : Terms of Astrology. From evening star to twin problem. Harri Deutsch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-8171-1785-7 .

- James Herschel Holden: A History of Horoscopic Astrology. American Federation of Astrologers, Tempe (USA) 2006 (2nd edition).

- Kocku von Stuckrad : History of Astrology. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50905-3 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jürgen Hamel : Concepts of Astrology . Scientific publisher Harri Deutsch, Frankfurt am Main 2010. P. 157 ff., Keyword prehistoric astrology and astronomy .

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad : History of Astrology , C. H. Beck, Munich 2003, p. 35 f.

- ↑ Stuckrad 2003, p. 37 f. See also John David North : Stonehenge. A New Interpretation of Prehistoric Man and the Cosmos. New York 1997.

- ↑ Stuckrad 2003, p. 42.

- ↑ Jürgen Hamel: Concepts of Astrology . Scientific publisher Harri Deutsch, Frankfurt am Main 2010. P. 139. Keyword Babylonian astrology .

- ↑ Stefan M. Maul: The art of fortune telling in the ancient Orient . C. H. Beck, Munich 2013. p. 17.

- ↑ Stefan M. Maul: The art of fortune telling in the ancient Orient . C. H. Beck, Munich 2013. pp. 261 f.

- ↑ James Herschel Holden: A History of Horoscopic Astrology. American Federation of Astrologers, Tempe (USA) 2006. p. 3.

- ↑ Mathieu Ossendrijver: Astronomy and Astrology in Babylonia , in: Joachim Marzahn , Beatrice André-Salvini, Jonathan Taylor, Babylon - Myth and Truth: Catalog for the exhibition in the National Museums in Berlin, Pergamon Museum, June 26, 2008 to October 5, 2008 . Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2008. p. 380.

- ^ Francesca Rochberg : Heavenly Writing . Cambridge University Press, New York 2004, p. 129 f.

- ^ Francesca Rochberg : Babylonian Horoscopes . American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia 1998. p. 45, p. 51 ff.

- ↑ Stephan Heilen : 'Hadriani genitura' - The astrological fragments of Antigonus of Nikaia . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015. p. 207.

- ↑ Jürgen Hamel: Concepts of Astrology . Science publisher Harri Deutsch, Frankfurt / M. 2010. p. 211 f.

- ↑ Stephan Heilen: 'Hadriani genitura' - The astrological fragments of Antigonus of Nikaia . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015. p. 237.

- ↑ Klaus Koch: Astrology II. Biblical . In: Religion Past and Present . Fourth, completely new revised edition, Vol. 1, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1998, Sp. 858 f.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology. C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 132.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology. C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 130

- ↑ Klaus Koch : Astrology II. Biblical . In: Religion Past and Present . Fourth, completely new revised edition, Vol. 1, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1998, Sp. 858 ff.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology. C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. pp. 129 f.

- ↑ Klaus Koch: Astrology II. Biblical . In: Religion Past and Present . Fourth, completely new edited edition, Vol. 1, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1998, Sp. 860; Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology. C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. pp. 137-140.

- ↑ Hubert Cancik, Helmuth Schneider (ed.): The new Pauly. Encyclopedia of Antiquity . Volume 2. Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 1997. p. 130 (keyword 'Astronomy').

- ↑ Bara, pp. 111f.

- ↑ John M. Steele, The 'Astronomical Fragments' of Berossos in Context , in: Johannes Haubold, Giovanni B. Lanfranchi, Robert Rollinger, John M. Steele (eds.): The World of Berossos: Proceedings of the 4th International Colloquium on 'The Ancient Near East between Classical and Ancient Oriental Traditions (Classica et Orientalia, 5). Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2013. p. 101.

- ^ Geert Eduard Eveline de Breucker: De Babyloniaca van Berossos van Babylon: inleiding, editie en commentaar . Groningen 2012. p. 27 f., P. 677. Publication available as PDFs , accessed on March 1, 2017.

- ↑ James Herschel Holden: A History of Horoscopic Astrology . American Federation of Astrologers, Tempe (USA) 2006. p. 9.

- ↑ John M. Steele, The 'Astronomical Fragments' of Berossos in Context , in: Johannes Haubold, Giovanni B. Lanfranchi, Robert Rollinger, John M. Steele (eds.): The World of Berossos: Proceedings of the 4th International Colloquium on 'The Ancient Near East between Classical and Ancient Oriental Traditions (Classica et Orientalia, 5). Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2013. p. 110.

- ↑ James Herschel Holden: A History of Horoscopic Astrology. American Federation of Astrologers, Tempe (USA) 2006. pp. 12-15.

- ^ Vettius Valens: Bouquets of flowers . Scripta Mercaturae Verlag, St. Katharinen 2004. pp. 204-211.

- ↑ Alexandra von Lieven , pigs, fish, insects and stars: About the remarkable life of the deans according to the plan of the course of the stars , in: Mark Geller, Klaus Geus (ed.): Productive Errors: Scientific Concepts in Antiquity , Reprint 430, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin 2012, p. 125. Published as PDF , accessed on March 13, 2017.

- ↑ Stephan Heilen: 'Hadriani genitura' - the astrological fragments of Antigonus of Nikaia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015. pp. 694–696.

- ↑ a b Bara, p. 112

- ↑ Gerd Mentgen: Astrology and the public in the Middle Ages . Anton Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2005. pp. 161 f.

- ↑ Stephan Heilen: 'Hadriani genitura' - the astrological fragments of Antigonus of Nikaia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015. P. 609 f.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology. C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. pp. 115 f.

- ↑ James Herschel Holden: A History of Horoskopic Astrology. From the Babylonian Period to the Modern Age. Tempe (Arizona, USA) 2006. p. 51.

- ↑ Stephan Heilen: 'Hadriani genitura' - the astrological fragments of Antigonus of Nikaia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015. p. 56, note 277.

- ^ Vettius Valens: Bouquets of flowers . Scripta Mercaturae Verlag, St. Katharinen 2004. P. 234 f.

- ↑ Stephan Heilen: 'Hadriani genitura' - the astrological fragments of Antigonus of Nikaia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015. p. 33.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 113.

- ↑ Stephan Heilen: 'Hadriani genitura' - the astrological fragments of Antigonus of Nikaia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015. p. 528.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 117.

- ^ Paul-Richard Berger: Rabbi Jehoshua ben Chanaja. In: Folker Siegert: Border Crossing: People and Fates between Jewish, Christian and German Identity . Lit, Münster 2002, ISBN 3-8258-5856-1 , pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. P. 150 ff.

- ↑ Marie Theres Fögen: The expropriation of fortune tellers. Studies on the imperial monopoly of knowledge in late antiquity . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1993. p. 12 f.

- ↑ Marie Theres Fögen: The expropriation of fortune tellers. Studies on the imperial monopoly of knowledge in late antiquity . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1993. pp. 20 f.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 122.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 124.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 123.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. P. 121 f.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 119.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 124.

- ^ Rudolf Drössler: planets, signs of the zodiac, horoscopes. An excursion into mythology, speculation and reality . Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1987. p. 12.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003, pp. 141-146.

- ↑ Klaus Koch: Astrology II. Biblical . In: Religion Past and Present . Fourth, completely new revised edition, Vol. 1, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1998, Sp. 859.

- ↑ Eclipses - whether the sun or the moon - were considered especially in the area of mundane astrology in antiquity, sometimes even today, as events and signs with extraordinary, mostly negative effects and meaning.

- ↑ Klaus Koch: Astrology II. Biblical . In: Religion Past and Present . Fourth, completely new revised edition, Vol. 1, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1998, Sp. 859 f.

- ↑ James Herschel Holden: A History of Horoskopic Astrology. From the Babylonian Period to the Modern Age. Tempe (Arizona, USA) 2006. p. 101.

- ^ Gerd Mentgen, Astrology and the Public in the Middle Ages . Anton Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2005. p. 168.

- ↑ Stephan Heilen: 'Hadriani genitura' - the astrological fragments of Antigonus of Nikaia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015. pp. 213–311 ('Greek Horoscopes'), p. 304 (astrologer in the vicinity of Justinia I.)

- ^ Gerd Mentgen, Astrology and the Public in the Middle Ages . Anton Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2005. p. 169.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2003. p. 121.

- ↑ James Herschel Holden: A History of Horoskopic Astrology. From the Babylonian Period to the Modern Age. Tempe (Arizona, USA) 2006. pp. 85 f.

- ^ David Pingree : From Alexandria to Baghdad to Byzantium. The Transmission of Astrology. , in: International Journal of the Classical Tradition , Vol. 8, No. 1, Summer 2001, pp. 3-37. P. 6 f.

- ↑ Hildebrand Beck: Providence and predestination in the theological literature of the Byzantines . Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, Roma 1937. p. 68.